Intro/FAQ ⎜ Episode 1 ⎜ Episode 2 ⎜ Episode 3 ⎜ Episode 4 ⎜ Episode 5 ⎜ Episode 6 ⎜ Episode 7 ⎜ Episode 8 ⎜ Episode 9 ⎜ Episode 10 ⎜ Episode 11 ⎜ Episode 12 ⎜ Episode 13 ⎜ Episode 14 ⎜ Episode 15 ⎜ Episode 16 ⎜ Episode 17 ⎜ Episode 18 ⎜ Episode 19 ⎜ Episode 20 ⎜ Episode 21 ⎜ Episode 22 ⎜ Episode 23

[Editor’s Note: This is the eighteenth in a series of 23 essays summarizing and evaluating Book of Mormon-related evidence from a Bayesian statistical perspective. See the FAQ at the end of the introductory episode for details on methodology.]

The TLDR

It seems unlikely that God would allow his prophets and scriptural texts to err as frequently as they do.

Some point to the verifiable mistakes of modern prophets, or apparent mistakes in the Book of Mormon, as evidence that the church or the book are inauthentic and uninspired. I argue that, if the book and the prophets that support it are authentic, they should be just as prone to error as are the prophets and text of the Bible. We note, alongside irreligious commentators, that the biblical text and the prophetic lives it describes are far from perfect themselves. After providing a rough estimate of how biblical prophets might differ from non-prophets in their ability to make mistakes, we conclude that prophetic and scriptural fallibility are poor standards by which to judge inspiration or authenticity.

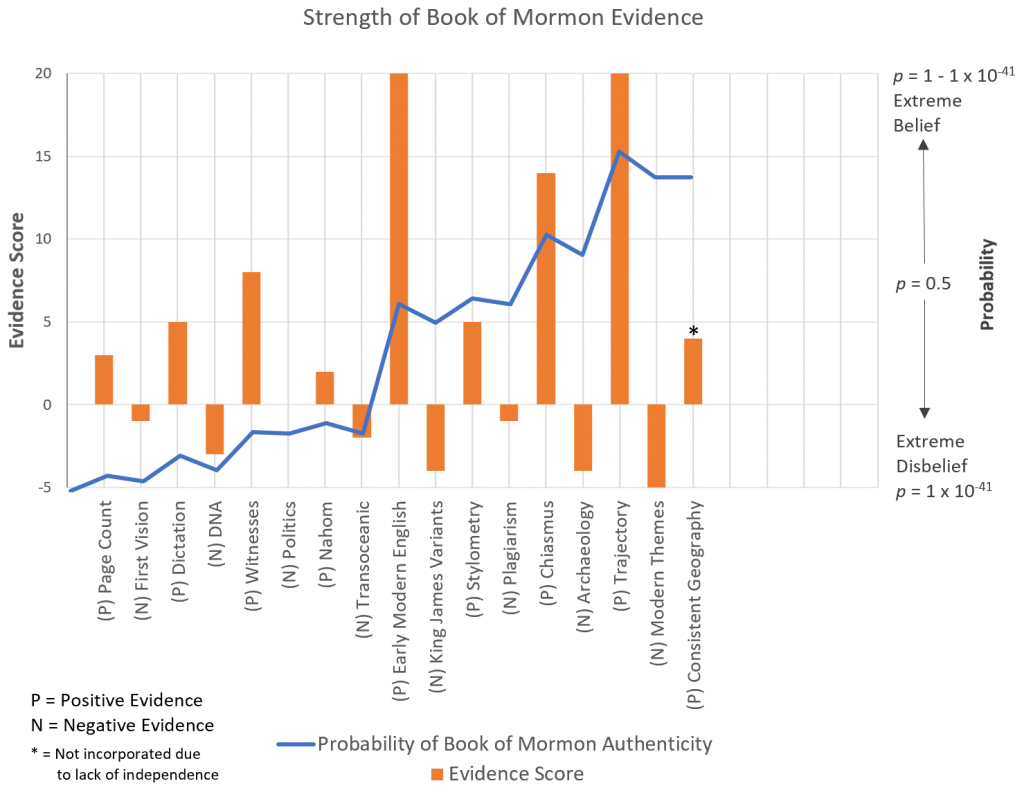

Evidence Score = -2 (reduces the likelihood of an authentic Book of Mormon by two orders of magnitude)

The Narrative

When last we left you, our ardent skeptic, you had been slogging through chapter after chapter of what seemed to be an interminable war between tribes that had been enemies for generations. Though you were a student of history, you always found depictions of battle to be tedious, and these chapters are no exception. Though you’re sure there would be many readers who would be enthralled and inspired by the heroic deeds of this Captain Moroni, you feel tempted to skip a few pages here and there. But, the dutiful reader you are, you force your eyes to cover every word, though in the quiet of the early afternoon you find your eyelids occasionally drooping down and getting in the way.

After a few more chapters you find a passage that starts to look a bit more interesting—the book takes a chapter away from battle to cover an interesting personal exchange between Captain Moroni and his

political counterpart back home by the name of Pahoran. The good Captain is less than pleased with the lack of support that the government has been offering him and his men, and boy does he let Pahoran have it, accusing him of betraying his people. You particularly enjoy one colorful passage:

I would that ye should adhere to the word of God, and send speedily unto me of your provisions and of your men, and also to Helaman. And behold, if ye will not do this I come unto you speedily; for behold, God will not suffer that we should perish with hunger; therefore he will give unto us of your food, even if it must be by the sword. Now see that ye fulfil the word of God. Behold, I am Moroni, your chief captain. I seek not for power, but to pull it down. I seek not for honor of the world, but for the glory of my God, and the freedom and welfare of my country. And thus I close mine epistle.

It’s hard not to be impressed with the Captain’s fervor, and you read on eagerly to see how and if this Pahoran might respond. But as you continue on you encounter a rather interesting twist. Moroni was mistaken! Pahoran’s government had been overthrown by traitors, and he writes back to Captain Moroni begging for his help to defeat those traitors and restore Pahoran to his position. Moroni, of course, does so, just in time to save the day, as all heroes do.

It’s a thrilling little bit of narrative, and a welcome injection of drama, but as your eyes keep moving from line to line, you can’t help but be bothered by something. The book you hold in front of you is one replete with miraculous events and angelic visitations at every turn. If the government was in such distress, why didn’t an angel visit Moroni and tell him exactly what was going on? Why did he let the Captain waste precious time relying on the vagaries of the postal service—if one even existed—to get the job done? Why did he let him be so wrong, even if all was right in the end?

The entire idea of a perfect and a just God made instances of such imperfection in his word, his servants, and his church difficult to tolerate—actually, no, it made them preposterous. What was the point of such a God if that God couldn’t be trusted to root out and prevent error? What was the point of calling and inspiring prophets if they were just as likely to be mistaken as they were inspired? You shake your head and move on, but the thought serves to bolster the lack of faith within you. It seems unlikely, you think, that God would allow his prophets and scriptural texts to err as frequently as they do.

The Introduction

One common line of argument from those critical of the church goes beyond the idea that church’s historical truth claims are inaccurate—e.g., that the Book of Mormon isn’t authentically ancient or that Joseph Smith didn’t receive heavenly visions—it suggests that the church’s present sources of truth are, themselves, not worthy of faith. They argue that modern prophets have been demonstrably mistaken on a number of issues, rendering the current doctrines and practices of the church no more divine, and perhaps even less divine, than other human institutions. Such an argument would almost amount to a truism in the absence of valid historical truth claims—if the Book of Mormon isn’t authentic, then it would be very hard for the modern church to be any more authentic. But that logic sometimes appears to work in reverse, with modern mistakes being used as evidence of past falsehood. If modern prophets are unreliable, why would we expect there to have ever been valid prophets in the first place?

We’ll ignore the logical gap inherent in that thinking (i.e., it would in fact have been possible for the church to have fallen away since the time of Joseph Smith) and concentrate on the principle underlying it. If the church is true (and the Book of Mormon, as the church claims, is authentic), should we expect modern prophets to have greater judgment and perception than other humans? To what degree should we tolerate their errors and personal failings? How imperfect does a prophet need to be before we can assume that he’s not actually a prophet?

As we work to answer those questions, we’ll also lump in a related problem. There are times when the events of the Book of Mormon appear to exceed the realm of plausibility—things like implausible population numbers or impossibly large armies engaged in combat. We could assume that because such things seem implausible that the book itself is implausible, but it could be that the prophets and record keepers of the Book of Mormon are themselves imperfect, exaggerating these kinds of details in a way common to other ancient historians.

The weight one places on this sort of evidence depends critically on the assumptions one applies to it. And though there’s admittedly not much for a Bayesian analysis to work with on the numbers side, what it’ll do is force us to make our assumptions as clear as possible.

The Analysis

The Evidence

To catalog the evidence here, we’re going to have to catalog some prophetic mistakes. We can consider this a sampling of the most public errors available from modern prophetic figures. I’ll emphasize that these are alleged errors—it’s certainly possible that each of these represent exactly what God would have preferred to happen. Obviously I don’t have the space to go into depth on any of these topics, but I’ve tried to link you to the most detailed scholarly sources available on each.

- Book of Mormon Copyright Sale. Though there’s a fair argument that the conditions of this prophecy weren’t met, the copyright for the Book of Mormon in Canada was not sold as predicted by Joseph.

- Temple in Independence, Missouri. The D&C is quite clear that a temple would be built on the temple lot in Independence, with the implication that it would be soon. We can hold out hope for the future, but it does seem to be a bit of an embarrassing delay.

- Kirtland Safety Society. It would be tough, indeed, to argue that Joseph made perfect and perfectly inspired decisions in his handling of the financial affairs of the church in the Kirtland period.

- Destruction of the Nauvoo Expositor. Though Joseph’s martyrdom may have ultimately been the will of God, there’s an argument to be made that destroying the Expositor’s press was a tactical error that did little to protect the saints and hastened the prophet’s demise.

- Joseph’s Polygamy. Though polygamy itself may have been divinely inspired, I think it’s fair to say that Joseph’s handling of polygamy was, at times, less than graceful.

- Joseph and the Moon. Joseph saw many things in his visions. The surface of the moon was not one of them. Though he probably didn’t say this, both he and Brigham likely believed it, as did a number of prominent scientific minds at the time.

- Joseph’s Millennial Prophecy. This one isn’t fair, since it’s obvious from the text that Joseph wasn’t at all sure what to make of the Savior’s cryptic communication, but in that case the mistake may have been in publicly sharing something that he wasn’t sure about.

- Queens of the Earth Paying Homage. Joseph made a rather bold prediction that the queens of the earth would pay homage to the Relief Society within 10 years of its founding. This doesn’t seem to have occurred.

- Calling Apostles Who Would Later Apostatize. There are a number of apostles who later would leave the church and fall short of their callings. An argument could be made that those issuing these callings could have exercised prophetic foresight and called only those who would remain faithful.

- Blacks and the Priesthood. Both the Gospel Topics essay and Elder Uctdorf have made clear that the church considers both the priesthood ban itself and the post-hoc justifications for it as grievous errors.

- Handcart Companies. This one’s definitely debatable, but the tragedy of the Martin and Willie Handcart Companies might not have happened if Brigham hadn’t chosen to institute handcarts in the first place.

- Mountain Meadows. Brigham’s role in the massacre remains controversial, and though I think the historians behind Saints vol. 2 make a strong argument that he did not approve of or have knowledge of the massacre beforehand, critics could sincerely ask why prophetic insight didn’t allow him to prevent it.

- Brigham’s Divorces. Brigham can’t take all the blame, since it takes two to tango, but the record would indicate that Brigham was not always the perfect husband (though I’m sure few mortals could ever succeed at spinning that many relational plates).

- Joseph Fielding Smith and Evolution. I have no doubt that President Smith’s views were sincerely held, and that the evidence for evolution wasn’t nearly as incontrovertible then as it is now. But he was wrong, and his stance continues to be a stumbling block for many.

- Forgeries of Mark Hoffmann. Though they had plenty of good company, it’s clear that the church was fooled, and fooled hard, by Mark Hoffman.

- Baptizing Children of Gay Couples. Regardless of the correctness of the doctrine, the relative swiftness with which this policy was revoked suggests that the brethren themselves realized it was a bad idea, both in terms of PR and in terms of unintended consequences.

We will add to that a few other purported errors to be found in the Book of Mormon, such as:

- Scale of Book of Mormon Battles. The scale of the battles that take place in the Book of Mormon tends to stretch credibility, particularly for the ones in Ether that involve millions of combatants.

- Population Problems. Though much of critics’ beefs with population numbers in the Book of Mormon is due to faulty assumptions about the peoples described in the book, at least one partial explanation is that the book’s ancient authors weren’t the most scrupulous of demographers.

We’ll take a moment here to call attention to the treatment of James Smith, a Latter-Day Saint expert in ancient demography, who shows that it’s possible to take a reasoned and reasonable accounting of Book of Mormon population numbers, suggesting that the values reported may not be as unrealistic as the critics claim.

It’s very important to avoid the pitfall of equating average historical growth rates (which are very low) with ones attached to a specific place and time, which is what the critics do when they discuss problems with Book of Mormon demography. As Smith notes, “to interpret simple textbook diagrams of world population growth in this way is wrong. Such diagrams obscure actual population dynamics in the past where fluctuation and change were the rule rather than the exception. In reality, populations in the past sometimes grew rapidly, sometimes remained fairly stationary, and sometimes declined precipitously, and the pattern of population change was far from smooth or sluggish.” Historical population growth generally follows a jagged pattern marked by periods of dramatic growth and dramatic collapse, which we can see quite clearly in the Book of Mormon narrative.

- Jaredite Ship Issues. Whatever one can say about the Jaredite crossing, it would not have been a good time. While we’ve already argued that a transoceanic voyage would be quite possible with ancient technology, the description provided in Ether does not present the most plausible image of a successful year at sea.

These latter three are generally used by critics as evidence that the Book of Mormon isn’t authentic, but that doesn’t have to be the case. We’re not trying to figure out if the Book of Mormon represents perfectly accurate history; we’re trying to figure out if it’s ancient. As we’ll see, ancient writing can be considered ancient in part because of, rather than in spite of, its imperfect recounting of history.

The Hypotheses

We’ll be considering two different hypotheses here:

Modern and Book of Mormon prophets make mistakes because they’re human—According to this hypothesis, though prophets occasionally receive divine inspiration, they do not possess the divine attributes of omnipotence or omniscience. As human beings who receive inspiration, we should expect them to make the same types of mistakes as other human beings who have received inspiration, most notably the prophetic and apostolic figures of the Old and New Testament.

This is in contrast to the following highly distinctive critical hypothesis:

Modern and Book of Mormon prophets make mistakes because they’re human—Though critics aren’t really on the exact same page as the faithful on this issue, they do posit the same source for prophetic mistakes. Critics see the prophets as people who are just as prone to error as any other non-inspired person. And there-in lies the critical difference—rather than placing prophets in the same category as other prophets, critics would place them in the same category as the non-inspired masses, or perhaps with other well-meaning but ultimately uninspired religious and community leaders.

By making that key distinction, we can establish an upper-bound on the evidentiary value of these sort of mistakes. I don’t really need to know how modern or Book of Mormon prophets stack up against those comparison groups (though hopefully we’ll get a sense of that as we go along). What really matters is the difference between biblical prophets and other humans. If that difference is broad, then it would be helpful to know which of those comparison groups Book of Mormon and modern prophets are most similar to. If the difference is relatively small, then knowing that wouldn’t be particularly helpful, since those prophets would make about the same amount of mistakes either way.

Discussing that difference will be the main focus of the rest of our analysis. But first, let’s review our priors.

Prior Probabilities

PH—Prior Probability of Inspired Prophets and Scripture—Based on the evidence we’ve considered in previous posts up to this point, our estimated probability of an authentic Book of Mormon (and, by extension, an authentic restoration) is a quite healthy p = 1—1.08 x 10-21. Here’s a summary of where I peg the strength of that evidence.

PA—Prior Probability of Uninspired Prophets and Scripture—If the probability of an authentic Book of Mormon is very high, that would of course mean that the probability of a fraudulent Book of Mormon is currently very low, in this case at p = 1.08 x 10-21.

Consequent Probabilities

CH—Consequent Probability of Ancient Authorship—I’ll be frank here, this is not a problem that’s amenable to precise statistical analyses. We’re going to have to make some tenuous statistical and inferential leaps along the way, but hopefully you can follow along for the sake of the thought experiment.

We’ll discuss both aspects of the issue in turn—the fallibility of prophetic figures, and the fallibility of scripture itself.

Prophetic errors. Our first job is to try to figure out how the mistakes of prophetic figures compare to the average person, and to do that we’ll need to examine the lives of some prophetic figures as they’re presented in the Old and New Testaments. As much as die-hard evangelicals maintain that the Bible itself is perfect, they do not hold the biblical prophets themselves to that same standard, and neither, for that case, does the D&C:

Behold, I am God and have spoken it; these commandments are of me, and were given unto my servants in their weakness, after the manner of their language, that they might come to understanding. And inasmuch as they erred it might be made known; And inasmuch as they sought wisdom they might be instructed; And inasmuch as they sinned they might be chastened, that they might repent; And inasmuch as they were humble they might be made strong, and blessed from on high, and receive knowledge from time to time. (D&C 1:24-28)

So, in short, we can expect to find accounts of prophetic figures making mistakes. I’ve assembled a general list below of a few select prophets, based on everyone’s favorite prophet-related Primary song, plus a few apostolic figures on the New Testament side (Peter, Paul, and John), minus Daniel (given the positive evidence suggesting that he wasn’t an actual historical figure), and a few less-notable additions (Nathan, Balaam, and David) to include some of the lesser-well-known prophetic figures. There’s likely a more methodical and complete way of selecting this kind of prophetic sample, but it will do for now.

It’s worth noting that basing our sample on biblical accounts is already biasing the analysis in favor of the critics, as these accounts should be much more inclined to favorably present the lives of these prophetic figures, particularly compared to the well-documented and exceptionally critical treatments modern prophets receive today. And the better these biblical prophets look, the higher a bar we’ll be asking our modern prophets to clear. On to the mistakes.

| Prophet | Purported Mistakes |

|---|---|

| Adam | We don’t hear much from Adam following the Garden of Eden, but one can imagine a critic asking why Adam’s prophetic status didn’t allow him to foresee and prevent the murder of Abel. |

| Noah | Noah is on record in the Bible as a pass-out drunk, which was a source of ridicule for (one of) his children. |

| Enoch | We don’t hear of any errors from Enoch in the biblical record. |

| Abraham | Many biblical commentators like to treat Abraham’s polygamy and his deception of Pharoah regarding Sarah as indications of error (though they don’t tend to point out the attempted murder of his own child), but neither of those would be considered errors in the context of LDS thought. We’ll actually be doing the critics a favor by adopting that perspective and overlooking Abraham’s more obvious faults. We’ll instead limit his mistakes to being prejudiced against Canaanites in advising his son on his choice of bride. |

| Moses | Moses made the rather grave error of disobeying God’s instructions when extracting water from the rock, as he then took credit for that miracle after the fact. |

| Balaam | Balaam is treated as a legitimate prophet early in the Old Testament, but is also treated later on as an example of unrighteous behavior. He is also portrayed as engaging in idolatry and teaching others to commit fornication (as well as a conspicuous case of animal cruelty). |

| Samuel | Samuel initially believed that Eliab would be the new king instead of David. He also set up his own sons as judges, who would later become corrupt. |

| Nathan | Nathan told David that the Lord approved of David’s plans to build the temple, advice that was later corrected by God. |

| David | It could be argued that David wasn’t considered a prophetic figure, but there is a variety of inspired material attributed to him (e.g., many of the Psalms). He was also, of course, an adulterer and a murderer, alongside his conducting an unauthorized census (horror of horrors). |

| Jonah | Jonah’s mistakes are a pretty salient part of his narrative. He ran away from his calling. He felt rather severe prejudice against the Assyrians, and he was angry when God didn’t destroy them. He could also be accused of giving a false prophecy, even though God clarified that the conditions of the prophecy were no longer valid. |

| Peter | Peter’s most obvious mistake was his denial of Christ (though some would argue that he did this at Christ’s instruction). In the early days of the church he believed that only Jews could be saved, though he would be instrumental in correcting this error. Even after this, though, he avoided new gentile Christians when important Jews came to town. He also rebuked Jesus openly when Jesus began to talk about his death and resurrection. |

| John | John was convinced that he was living in the “last hour” (or “last time” in the KJV rendering), despite the fact that a few million hours have passed since he said those words. |

| Paul | Paul was pretty open about his own weaknesses. Even besides that, he famously forbade women from speaking in meetings, demonstrating a rather severe sexism. Paul also ignores the warnings of the other disciples (which they gave “through the spirit”) that he shouldn’t go to Jerusalem. |

All things considered, I can imagine Joseph Smith or Brigham Young fitting in very comfortably in this group when it comes to their fallibility. Now, I’ve given these in rough chronological order, but we could order them somewhat differently. Here’s my personal ranking (note the dreaded red text) of these prophetic figures in terms of the severity of these mistakes (from least severe to most severe), along with a brief summary of those errors:

| Prophet | Purported Mistakes |

|---|---|

| Enoch | No recorded errors. |

| Adam | Failing to prevent tragedy. |

| John | Misjudging the timing of the second coming. |

| Nathan | Incorrectly speaking in the name of the Lord. |

| Samuel | Misjudging character. Nepotism. |

| Abraham | Prejudice against Canaanites. |

| Noah | Drunkenness. <--- AVERAGE PROPHETIC IMPERFECTION |

| Moses | Disobedience. Taking credit for others’ accomplishments. |

| Paul | Sexism. Ignoring divine guidance. |

| <--- MISTAKES MADE BY AN AVERAGE PERSON | |

| Peter | Denying Christ. Racism. Overzealousness. |

| Jonah | Running away from a divine calling. Racism. Failed prophecy. |

| Balaam | Idolatry. Encouraging fornication. Animal cruelty. |

| David | Adultery. Murder. Unauthorized census taking. |

Notice a couple of things that I’ve done here. First, I’ve marked Noah as the median within our set of prophetic figures, with six others above (topped by Enoch’s Zion-studded piety) and six others below (with David’s shameful legacy sitting on the very bottom). For the sake of our analysis, we’ll assume that Noah represents the midpoint of the prophetic mistake-making scale, with our population of prophets normally distributed around it. Some few are near perfect. Some few are very, very bad. Most everyone has a few notable but minor flaws.

Importantly, I’ve also marked the spot where our non-prophetic “average person” would be in terms of mistake-making (particularly, where they would have been in the ancient period). Stuff like sexism, disobedience, and drunkenness would have been par for the course. Adultery, murder, and denying one’s affiliation with someone you believed to be a living God, probably less so. (Though not unheard of, obviously. Fun fact: 21% of men and 13% of women will cheat on their romantic partner over the course of their lifetime.) Most of our prophets would be above that average, but some would be below it.

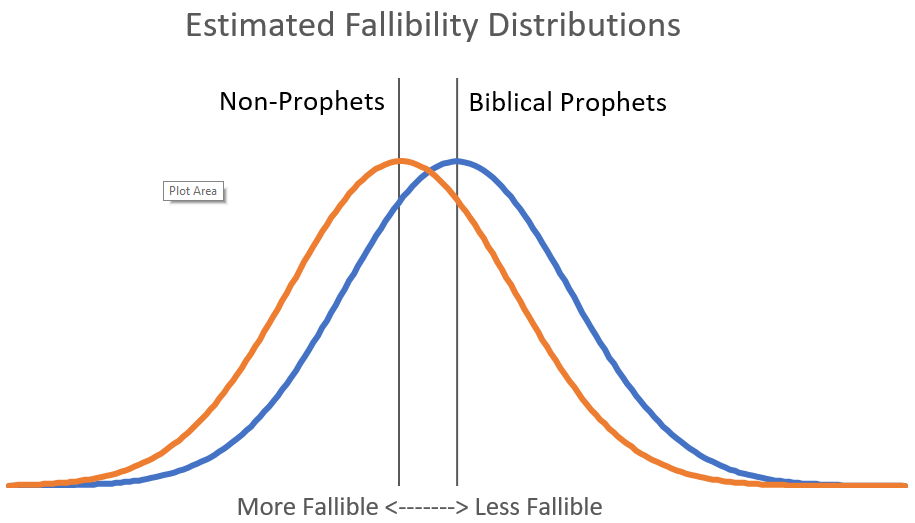

Marking those two spots allows us to make a guess as to how different those two distributions are in statistical terms. We can take the proportion of prophets that fall below the “average person” standard and turn that into a Z-score separating those two distributions:

p = 4/13 = .30769

That probability corresponds with a Z-score of almost exactly = -.5, meaning that the average person would be half a standard deviation below the average prophetic figure. That’s actually a respectable effect size when it comes to measuring differences between groups—not overridingly large, but nothing to sneeze at either. You can see what that looks like in the figure below.

Once we have that value, we can bring our modern prophets into the mix. Again, we’re accepting the critics’ argument that modern prophets are no less imperfect (and no more imperfect), on average, than other people. Based on that assumption, we can take our stable of 17 modern prophets and assume that they make as many mistakes, on average, as the average person. From there, we can ask how likely we’d be to see that result if they, in actuality, belonged to the same distribution as authentic biblical prophets. And, conveniently, we can use a one-sample t-test to give us a workable answer.

| t(df) = | X — μ |

| s / √n |

X sample mean) = —.5 (modern prophets assumed to be half a standard deviation less fallible than ancient prophets)

μ (known population parameter) = 0 (placing the mean of ancient prophets at 0)

s (standard deviation) = 1 (setting the standard deviation for ancient prophets to 1)

n (sample size) = 17 (the number of prophets in the modern dispensation)

df (degrees of freedom) = n — 1 = 16

| t(16) = | —.5 — 0 |

| 1 / √17 |

t(16) = —.5 / .242

t(16) = —2.06

One-tailed p = 0.028025

That leaves us with the odds of seeing a set of 17 modern prophets that are just as imperfect as everyone else as just over 1 in 50. Not high, but a long way from impossible. We’ll keep that p value in our back pocket for now and turn to the problem of imperfection in scripture.

Biblical errors. When it comes to errors in biblical scripture, I’m happy to report that atheist writers of various stripes have already done the heavy lifting. You don’t have to look very hard to get very thorough (as well as thoroughly obtuse) lists of contradictions and errors in the Bible. For instance:

- In the Gospel of Matthew at one point the author says he’s quoting Jeremiah, but he’s really quoting Zechariah (though of course it’s possible that Zechariah is ultimately quoting an unknown work of Jeremiah).

- Disagreement about who was high priest when David entered the temple unlawfully.

- Disagreement over the number of fighting men in Israel. (Note also that the number of fighting men reported are far higher than reported at the final battle at Cumorah in the Book of Mormon.

- Problematic population counts for the nation of Israel during the Exodus.

- At least 97 other notable errors.

Overall, it’s fair to say that the Bible is not a perfect document, and though this is a considerable issue for the doctrinal position of evangelicals, it’s not the least bit worrisome to Latter-Day Saints. In fact, one could predict in advance that those types of imperfections could be there. As James Smith writes:

Ironically, this issue concerning population counts in Numbers does not challenge the ancient origin of the biblical text as much as it supports it. If there is any hallmark of ancient historical records, it is their strong tendency to present puzzling, unrealistic, and inconsistent population figures.

In fact, if we take a look at other authentic ancient documents, there are plenty of concrete examples of error, such as:

- Disagreements over the population of Roman Egypt (3 million vs. 7.5 million).

- Josephus showing a dramatic pro-Jewish bias in his writing.

- Historical accounts reporting a thoroughly incredible value of 4.2 million men in the Persian army of Xerxes, alongside numerous examples of false strengths of Greek and Roman armies presented in ancient records.

- Herodotus dramatically exaggerating the magnificence of Babylon, among a variety of other impressive errors.

It’s worth noting that much of Herodotus’ errors can be attributed to the fact that he wasn’t a first-hand source for the stories he told. Much of his work was compiling information from a variety of other ancient (often mythical) sources, who were probably the ones doing most of the exaggerating. It was, admittedly, very hard to conduct rigorous fact checking in the ancient world. But if that sort of thing could apply to Herodotus, it’s certainly possible that it could apply to Ether as he recounts 30 generations worth of founding narrative for the Jaredites, or to Moroni himself as he abridges the Book of Ether, or even the Book of Mormon more generally.

So, both biblical and non-biblical ancient sources have a variety of errors and exaggerations in them. So what? How can we incorporate this into our estimate? Well, it’s possible to treat this problem as an extension of the first. Scriptural imperfections could be considered to just be another form of prophetic imperfections, especially as prophets are often the ones writing them (or approving of treating them as inspired and canonical). Because of this, we can just add these prophetic figures to our sample size. If we go through this list and pick out the major prophetic contributors to the Book of Mormon text, we can add Lehi, Nephi, Jacob, Enos, Benjamin, Alma, Alma the Younger, Amulek, Helaman, Nephi, Mormon, Moroni, and Ether, for a total of 30 prophetic figures in our sample. We can go ahead and recalculate that now:

t(29) = 2.74

One-tailed p = 0.00522

So that changes things a bit, but not dramatically so. Based on our rough estimate of the difference between prophetic and non-prophetic fallibility, it would absolutely be possible to see authentic prophets and scripture that look in many ways like their non-inspired counterparts.

CA—Consequent Probability of Modern Authorship—For the purposes of this analysis, we’ll make the assumption that the mistakes made by modern prophets and by the Book of Mormon perfectly align with the mistakes made by non-inspired persons (though a strong argument could be made that their personal habits are substantially more circumspect than average), meaning our estimate for the consequent probability for the alternate hypothesis would be p = 1.

And with that, we can complete our analysis.

Posterior Probability

PH = Prior Probability of the Hypothesis (our prior guess as to the likelihood of an authentic Book of Mormon, based on the evidence we’ve already considered, or p = 1 — 1.08 x 10-21)

CH = Consequent Probability of the Hypothesis (the estimated probability of observing a set of authentic prophets, prophets who are as fallible as non-prophets, or p = .00522)

PA = Prior Probability of the Alternate Hypothesis (our prior guess about the likelihood of a fraudulent Book of Mormon, based on earlier evidence, or p = 1.08 x 10-21)

CA = Consequent Probability of the Alternate Hypothesis (the estimated probability of observing a set of non-prophets who are as fallible as other non-prophets, or p = 1)

PostProb = Posterior Probability (our new estimate of the probability of an authentic Book of Mormon)

| PH = 1 — 1.08 x 10-21 | |

| PostProb = | PH * CH |

| (PH * CH) + (PA * CA) | |

| PostProb = | (1 — 1.08 x 10-21 * .00522) |

| ((1 — 1.08 x 10-21) * .00522) + ((1.08 x 10-21) * 1) | |

| PostProb = | 1 — 2.07 x 10-19 |

Lmag = Likelihood Magnitude (an estimate of the number of orders of magnitude that the probability will shift, due to the evidence)

Lmag = log10(CH/CA)

Lmag = log10(0.00522 / 1)

Lmag = log10(0.00522)

Lmag = -2

Conclusion

The above analysis suggests that the presence of prophetic errors is a relatively poor bar with which to judge the Book of Mormon. And remember that this represents what I’d consider to be an upper bound on the potential strength of this evidence. It would be perfectly valid to make a somewhat different argument, attempting to show that modern prophets are actually much closer to the biblical prophetic standard than to the “average person” standard, if not even higher. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if such evidence ended up working in the Book of Mormon’s favor.

Note that I’m not saying that imperfections in the Book of Mormon would themselves be considered evidence that it’s authentically ancient. But neither are those imperfections evidence that the Book of Mormon is ahistoric. If the book is ancient, the Bible, along with other ancient documents, represents the proper point of comparison. Given how riddled those ancient and (occasionally) inspired documents are with human error, it’s not unfair to expect the same of an authentic Book of Mormon.

But then why, you may ask, would the Book of Mormon ever be considered the most correct of any book on earth? And why would anyone ever follow a religion governed by demonstrably imperfect people? The answer, I think, hinges on Joseph’s clarification to that infamous statement, that those who abide by its precepts would get nearer to God than by any other book, and, by extension, any other church. The Book of Mormon’s, and the church’s, claim to correctness is found not in the perfection of its history or its demography or its policies, but in terms of whether it actually gets people closer to God, in spite of its imperfections. That question is a separate one from the questions of authenticity and historicity, and likely one that Bayes can’t answer for you.

Skeptic’s Corner

With all that said, are there ways that this analysis could’ve been done better? I’m sure there are ways it could be done differently, but I don’t see much benefit to trying to make a more rigorous version of what I’ve done here. You could get a more complete inventory of prophets and their mistakes (or you could toss out stories like Jonah’s, which has about the same chance as Daniel’s of being historical), but since we only ever get a small slice of the lives of biblical prophets, that more complete inventory wouldn’t necessarily be a more accurate view of how those prophets lived.

An alternative would be to argue that some mistakes, like, say, Joseph’s polygamy, are so egregious as to be immediately disqualifying. But I don’t see how that would be any more amenable to analysis. Everyone’s obviously free to form their own views on what is and isn’t disqualifying, but what are the odds that those views are wrong? Are they similar odds to someone having incorrect political stances? If so, then this evidence could just as easily be assigned a 0 instead of a -2.

If I readily admit that this type of evidence isn’t amenable to a Bayesian analysis, what’s it even doing here? Well, it’s here because it’s negative evidence, and, strong or no, it needs to be given its due. It would’ve been easy enough to just say throw a single sentence at the top saying “prophets are allowed to make mistakes, lolz” and call it a day. But as much as I might disagree, there are quite a few people who feel legitimate concern when learning about these mistakes, and it’s important to acknowledge that. I thus did my best to find the most meaningful way to assign a weight for this evidence.

More important than that, though, is the story that this analysis helps to tell. The primary narrative in the critical literature hinges on a generally unspoken assumption: that only perfectly inspired prophets—the prophets that we might have grown up with in Primary and Seminary—are worth following. But there’s an alternative narrative, and one which this analysis helps to make concrete: that imperfect prophets are the only ones that’ve ever been followed, from Adam on down. Even if every modern and Book of Mormon prophet is no different than the rest of us, it’s no reason to reject them or the revelations that came through them. That, I think, is a story worth telling, even if the analysis itself may not be.

Next Time, in Episode 19:

When next we meet, we’ll take an initial stab at analyzing the linguistic evidence connecting the Uto-Aztecan language family to languages of the Old World.

Questions, ideas, and lists of my personal imperfections can be sent to BayesianBoM@gmail.com or submitted as comments below.

It is understood that this particular episode was at least as difficult to measure as were all the previous. The task which Dr. Rasmussen has set for himself is not trivial and obviously has roots and branches which could be followed to almost any path of investigation. The fact that he narrows the process down and comes up with a measurable, quantifiable hypothesis is commendable.

That said, it is incredibly difficult to know exactly what someone was thinking, even when they voiced their thoughts. Even direct recordings or written analyses of our brain’s musings, still do not expose us to every nuance nor neural pathway NOT included in the recorded musing. For instance, in my mind at this moment, I’m thinking about Joseph F. Smith, BUT I’m also thinking about Brigham Young, even though Joseph F. Smith is the only one whom I’m going to mention. (I’m absolutely 100% certain that Joseph F. Smith would love to be able to explain his thoughts to us today, if he were able.)

So it is that oftentimes we say one thing and do another, or we say one thing and believe another. This is why Dr. Rasmussen’s approach is to just pick a point A or B and to then proceed with that selected point. Otherwise the analysis would never get off the ground. Commendations for just being able to proceed, Dr. Rasmussen!

I used to think about the difficulty of “large” population bases as described in the Book of Mormon. Apparently, I wasn’t the only one as this episode by Dr. Rasmussen reveals.

One day, I was reading about recent archaelogical evidence, especially as using LIDAR in the Mayan lowlands where human habitation had long been discounted. The evidence as revealed suggested that instead of the 1 or 2 million previously proposed, upwards of 20 million people could have been living in and around the main city, Tikal! That quantity is impossible to ignore and critics might have taken notice, but have failed to respond rationally. More importantly to the current discussion is the fact that scientists erred and erred badly! Previously where 1 or 2 million maximum was projected to habitate, at least 20 million are now acknowledged to have lived! That’s an error of magnitude 10 and somewhat egregious as per my current opinion of “scientific concensus.” So much for the “infallibility” of scientists as opposed to the Book of Mormon and its “laughable” large density human interaction.

c.f.: https://www.youtube.com/watch?reload=9&v=7MFKy7DJsCY

or: https://www.foxnews.com/tech/mysterious-lost-maya-cities-discovered-in-guatemalan-jungle

or: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20180201006278/en/Lost-Treasures-of-the-Maya-Snake-Kings-Rewrites-History-as-New-National-Geographic-Special-Reveals-Unprecedented-Scale-and-Sophistication-of-Mysterious-Ancient-Civilization

November 4, 2021

On Imperfect Prophets

Hi Kyler,

I think you have done a very good job here in threading a difficult and potentially controversial needle. I would like to add/reinforce a couple of thoughts—but I hope without creating too much controversy.

There is a joke that when the Pope claims infallibility, no Catholic believes it but that when the Prophet states clearly that he is not infallible, no Mormon believes it. It is an exaggeration, but it has a large kernel of truth, and perhaps too many Latter-day Saints lean strongly toward prophetic infallibility.

In my view, that strong leaning makes them spiritually vulnerable.

I really don’t understand why this should be so. Joseph Smith said clearly that he was a prophet only when he was speaking as a prophet…and then he made sure some of his mistakes were canonized in our scriptures for everyone to see. Talk about brutal honesty.

For my part, I see divine fingerprints all over the Restoration and I also see human fingerprints all over it. I don’t know how God is going to do his work using imperfect mortals without us dimwits making lots of mistakes. That fact doesn’t shake my faith: it strengthens my faith.

Now perhaps I will cause controversy without wishing to, but I am going to state my opinion and see where it leads.

In my opinion, I think the Church could and should do a lot more to strengthen its members against the mistaken and spiritually dangerous idea of infallibility on the part of its leaders.

When I read your statement that the Church had acknowledged the error of our past unscriptural, very long, uninspired policy of denying the priesthood to blacks of African descent, I was surprised but also elated. I was elated because I was unaware that any such acknowledgement of what can only be described as a huge mistake had been made.

So I read both Elder Uchtdorf’s conference address and the Gospel Topics essay…twice. But I didn’t find any clear statement, especially by Elder Uchtdorf, that that particular policy was a grievous mistake. It is perhaps implied, but not clearly stated.

Also, the Gospel Topics essay, at least in part, seems to try to justify the policy in terms of societal practices and attitudes of the time, while stating that the Church disavows racism and the unscriptural justifications advanced to support the policy.

But God has never cared about societal practices—in fact, God condemns our mores and morals pretty routinely. So that partial justification bothers me also. Why not just admit it was a huge mistake? Anyway, that is where I am on that issue.

I don’t have any trouble at all with imperfect people being led by imperfect prophets. I am grateful for it. But I do wish we would do a lot more to teach our people that it is our individual responsibility to know when the prophets are speaking as prophets, and when they are giving us the best counsel they can, as fallible human beings.

One current example to illustrate (also likely to ruffle some feathers): the First Presidency has urged (not “commanded”) us to be vaccinated against Covid-19, stating that the vaccines are “safe and effective”.

I really wish they had instead encouraged us to be vaccinated if our age and risk profile (comorbidities) indicated that vaccination was prudent. And I really, really wish they had also stated, as President Nelson did when he received the vaccine, that to be vaccinated or not was an individual decision.

Why do I wish that? Well, safety is always a relative concept. Safer than what? There is always at least some risk when you inject a foreign substance in your body. And as for “effective”, it is now obvious that, depending on your age group, the effectiveness of the available vaccines declines pretty rapidly with time. So boosters are now being widely pushed.

I personally believe that in time we are going to recognize that these vaccine mandates were a huge mistake, both in terms of our social cohesion and the health of many people. Anyone under the age of 40 is essentially free from the risk of death due to the vaccines, but they are not immune to the risk of myocarditis/pericarditis and other vaccine adverse effects, for which the evidence is rapidly mounting.

I believe that some Latter-day Saints will be injured by the vaccine and, unfortunately, may blame the Prophet for what was counsel, not a commandment. They may lose their faith instead of realizing that the burden was on them to think, study and pray about vaccination, then make up their own minds, make their own decision.

This process of thinking, studying and praying to find out for ourselves is the approach we need to bring to all issues, including the statements of inspired, but not infallible, prophets.

Bruce

” I didn’t find any clear statement, .., that that particular policy was a grievous mistake”

Shortly after the 1978 revelation to Pres Kimball and the Brethren, Elder McConkie made this very explicit statement in a speech at BYU:

“There are statements in our literature by the early Brethren which we have interpreted to mean that the Negroes would not receive the priesthood in mortality. I have said the same things, and people write me letters and say, ‘You said such and such, and how is it now that we do such and such?’ And all I can say to that is that it is time disbelieving people repented and got in line and believed in a living, modern prophet. Forget everything that I have said, or what President Brigham Young or President George Q. Cannon or whomsoever has said in days past that is contrary to the present revelation. We spoke with a limited understanding and without the light and knowledge that now has come into the world.” https://speeches.byu.edu/talks/bruce-r-mcconkie_alike-unto-god-2/ .

Many of us already knew that Brother Brigham was wrong, and that what he taught was directly contrary to the teaching and practice of Joseph Smith, but we also knew that all prophets are fallible, so that it was not at all shocking.

Individual LDS members often have their own preferred political and religious hobby horses, and demand that their fallible leaders give them infallible guidance in accord with their preconceptions. They are bound to be disappointed. Instead, they need to take responsibility for their own actions, and to take the time to read and be well-informed on their own account.

Thanks for your comment, Bruce.

I would be amenable to the church making even clearer statements disavowing the priesthood ban, but I read the following statement as stronger than mere implication:

From the Gospel Topics essay: “Today, the Church disavows the theories advanced in the past that black skin is a sign of divine disfavor or curse, or that it reflects unrighteous actions in a premortal life; that mixed-race marriages are a sin; or that blacks or people of any other race or ethnicity are inferior in any way to anyone else. Church leaders today unequivocally condemn all racism, past and present, in any form.”

If the instituting of the priesthood ban was fueled by racist ideas (which the rest of the essay makes a strong historical case for), then the ban itself would count as part of the past instances of racism that the church is universally condemning.

From Elder Uctdorf’s talk: “We openly acknowledge that in nearly 200 years of Church history—along with an uninterrupted line of inspired, honorable, and divine events—there have been some things said and done that could cause people to question…And, to be perfectly frank, there have been times when members or leaders in the Church have simply made mistakes. There may have been things said or done that were not in harmony with our values, principles, or doctrine.”

I’ll admit that my memory here failed me–I thought I remembered him talking more explicitly about the priesthood ban, but you’re right, he doesn’t. It was certainly the issue in my head when he talked about things being said in our 200 year history that could cause people to question, and I have to assume that it was one of the issues in his head too. But I’m happy to eat crow here. Though his talk is an excellent resource for discussing the imperfect nature of prophets, I shouldn’t have linked it to a specific acknowledgement of the priesthood ban as a grievous error. Thanks for helping me see that more clearly.

I really wish people would stop throwing Joseph Fielding Smith under the bus on evolution. Contrary to your assertion, the evidence for Darwinian evolution is not only NOT “incontrovertible,” it is becoming less so every year.

I invite you to read (really read, yourself, not just critical reviews) any one book from the below short list and see if you still think that the evidence for evolution is “incontrovertible.”

I could have made this list much longer. Ongoing discoveries in paleontology, biology, and molecular genetics make the neo-Darwinian evolution story not only not incontrovertible, but increasingly implausible.

Go ahead, pick just one, and really read it.

Signature in the Cell – Stephen Meyer

Darwin’s Doubt – Stephen Meyer

The Edge of Evolution – Michael Behe

Darwin Devolves – Michael Behe

A Mousetrap for Darwin: Michael Behe Answers His Critics – Michael Behe

The Devil’s Delusion: Atheism and its Scientific Pretensions – David Berlinski

Theistic Evolution: A Scientific, Philosophical, and Theological Critique – ed. by J.P. Moreland, Stephen Meyer et. al.

Thanks for the comment, David. I’ve read three of those (Signature, Darwin’s Doubt, and The Devil’s Delusion) and greatly enjoyed them. I suspect we’re on the same page on a lot of things. But though Meyer, Behe, and Berlinski cast significant doubt on the current neo-darwinian narrative, none of them would refute–and indeed, they generally assert–that random mutation and natural selection are real phenomena that result in evolutionary change and speciation. They just maintain that mutation and natural selection aren’t the whole story, and that they aren’t capable of either 1) the initial creation of life from base chemicals, or 2) the speed of speciation and body-plan development observed during, for instance, the Cambrian Explosion.

Joseph Fielding Smith’s position was not nearly so nuanced, and I have no problem saying that his views were mistaken. I suspect if he were alive today that he would much prefer the current arguments put forward by ID proponents than the young-earth creationist arguments of his era. But he’s not alive today, and he was alive then, and even as a prophet he’s allowed to have been shaped by the views of his era, just as Brigham was shaped by his, and President Nelson’s are shaped by today’s.

In fact, it’s important that we clearly state that he was mistaken. I know too many members who believe that because Joseph Fielding Smith was a prophet, his views on young-earth creationism must be correct. These individuals alter their entire worldview and contort the available evidence in order to maintain the former prophet’s stance as true and correct. People like that need to know that they don’t need to do this, and that the truth of the gospel and the restoration can be maintained without treating prophetic views and actions as if they were infallible. We can accept truth wherever we find it, and we can accept error wherever it rears its head, even when its found in the mouths of our own respected leaders, past and present.

Happy to discuss further, David, and thanks for sharing your thoughts.

While it is helpful to point out the fallible nature of ancient and modern prophets, there is a very important distinction which you failed to make: The Bible is actually an ancient document, despite flaws gained in transmission, while the Book of Mormon appeared only very recently — without ancient manuscripts attesting to its antiquity. That should make them largely incommensurable, unless there are forensic elements which give the BofM some ancient credibility, a credibility which should be impossible in a miraculous modern document. Thus bringing in a Bayesian notion that a preponderance of hard evidence should be impossible in a modern document and so making the BofM impossible to refute, and simultaneously providing cover for the impossible miracles contained in the Bible (a subject which bedevils evangelical apologists). A Second Witness indeed.

That brings in the question of your list of BofM flaws in demography: Not only in speed of population growth, but in absolute numbers in battle.

It turns out, for example, that the ancient Olmecs (coterminus with the Jaredites) and their successor cultures had populations in the millions. It should have been no problem to field such large BofM populations. In fact, I recall 50 years ago a young Jewish PhD in archeology specializing in Oaxaca recommending that I read Wittfogel on Oriental Despotism to understand the anthropology and massive irrigation systems of ancient Oaxaca, Mexico — certainly part of the Olmec sphere of influence.

If we consider only the Olmec heartland @ about 7,000 square miles (which was very fertile and carefully leveed), and apply Gordon Willey’s estimate of 777 people per square mile in the densest Maya areas, that would give up to 5 million pop in the heartland alone. Willey, “Pre-Hispanic Maya Agriculture: A Contemporary Summation,” in P. D. Harrison & B. C. Turner II, eds., Pre-Hispanic Maya Agriculture (Albuquerque: Univ. of New Mexico, 1978), 325-326. Even half that would still be a considerable non-urban population.

However, the area occupied by the Olmec was much larger than that. They raised crops such as maize (2 crops per year), yams, squash, beans, avocados, chiles, cacao, rubber, etc., with planned, intensive irrigation systems.

Thanks Robert. You bring up a good point–that the demography of the New World could certainly make the details provided in the BofM more plausible than we might otherwise think. My only point is that exaggeration could be still coming into play here, and that such would fit well with what we’d expect from an ancient document. Mormon and Ether don’t need to be wrong, but they may have been, and if they are that’s okay. We don’t need to hang our testimonies on whether the Olmecs were able to field millions of combatants, a fact which I hope could encourage patience in those that have trouble creating that mental image, rather than using it as fuel for doubt.

Thanks again, Robert. I’m very glad to have you still reading these.