Intro/FAQ ⎜ Episode 1 ⎜ Episode 2 ⎜ Episode 3 ⎜ Episode 4 ⎜ Episode 5 ⎜ Episode 6 ⎜ Episode 7 ⎜ Episode 8 ⎜ Episode 9 ⎜ Episode 10 ⎜ Episode 11 ⎜ Episode 12 ⎜ Episode 13 ⎜ Episode 14 ⎜ Episode 15 ⎜ Episode 16 ⎜ Episode 17 ⎜ Episode 18 ⎜ Episode 19 ⎜ Episode 20 ⎜ Episode 21 ⎜ Episode 22 ⎜ Episode 23

[Editor’s Note: This is the ninth in a series of 23 essays summarizing and evaluating Book of Mormon-related evidence from a Bayesian statistical perspective. See the FAQ at the end of the introductory episode for details on methodology.]

The TLDR

It seems unlikely that Joseph or his scribes could fill the Book of Mormon with examples of grammar and word use that fit better in Early Modern English than in the nineteenth century.

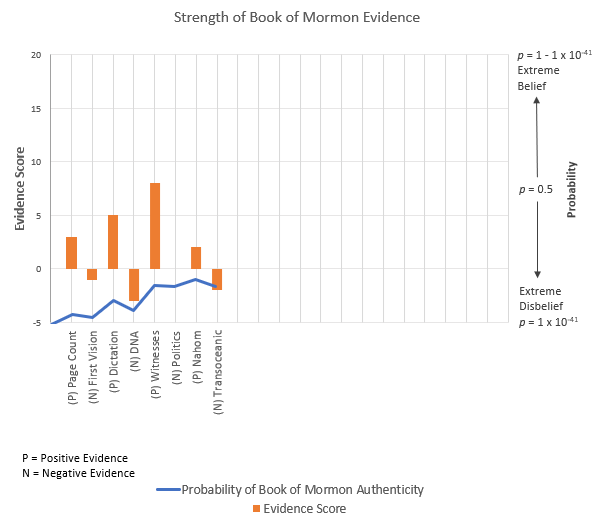

Stanford Carmack and Royal Skousen have painstakingly documented a strange argument—that much of the language used in the Book of Mormon reflects usage patterns that align with the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, making it unlikely that Joseph or anyone else in the nineteenth century authored the book. The statistical case they make is extremely strong. Even assuming that they’re missing a substantial amount of evidence that doesn’t fit their narrative, the probability that Joseph produced those patterns by trying to copy biblical style are vanishingly small (p = 5.24 x 10-24). Evidence of Early Modern English can be counted as powerful evidence in favor of the Book of Mormon’s authenticity.

Evidence Score = 20+ (A critical strike in the Book of Mormon’s favor, increasing the probability of authenticity by over 20 orders of magnitude).

The Narrative

When last we left you, our brave skeptic, you had left behind deep thoughts about the absurdity of amateur boat-building just as this Nephi and his family entered what you assumed to be the New World. You almost can’t wait to see how this fractured family deals with life in paradise, and just how much (or how little) of a paradise this promised land turns out to be. It’s far too early in the book for there to be any hint of a happy ending.

But you don’t make it more than a few verses before you stumble onto a strange turn of phrase in the text. The stumbling part was more than a metaphor—you can almost feel your mind tripping over the words and falling flat on its face, your weary mind unable to move past them or parse the meaning.

"Wherefore, I speak unto all the house of Israel, if it so be that they should obtain these things.”

The phrase “if it so be that” may have sounded biblical, but you are pretty sure that you haven’t seen it in the Bible. You’d noticed archaic phrasing like that before, but this is the first time you stopped to think about it. You had assumed that much of the bad or strange grammar you’d encountered up to this point had been a mixture of Smith’s clearly insufficient backcountry education and his attempts to emulate biblical style.

But you realize something strange. You’d seen that turn of phrase before—not in any other book of the modern era—but you’d seen it, nonetheless. You put down the book and turn again to the small but trusty bookshelf at the edge of the cabin, thumbing through the worn spines of the oldest tomes in your collection. You come quickly to the one you’d been thinking of, The Canterbury Tales, published in 1400. You wonder if you will be able to find what you’re looking for, but as you crack open the aging book your finger lands almost miraculously on the passage you’d been thinking of.

“Thus moche amounteth al that ever he ment, if it so be that I have it in mynde.”

Had Smith read his Canterbury Tales? You suppose that he might have. But the thought doesn’t leave you as you move again to the Book of Mormon and pore over the page you’d been reading. Were there more of these? And if there were, what on earth were you to make of them?

What you experience next can only be described as transcendental. A window opens in your mind and you find your thoughts transported to an other-worldly realm. It’s as if you’re awash in a sea of words from thousands of books, and as your thoughts swim through them you can feel and know them all, their meaning filling every pore. As the literary waves crash over you, you feel a familiar linguistic thread in the water—they’re the words from Smith’s book, not just the ones you’d read, but all of them—every syllable that lay within the covers. Your skin pricks with its phrases, many of them unfamiliar, many of them strange, and as they penetrate you feel the same phrases reaching into you from dozens of other books. Their titles flash before your mind’s eye. Some you had read; many of them you hadn’t. But somehow you knew that all of them were old, almost archaic—older even than the King James itself. The phrases had a ring of authenticity that you couldn’t dismiss as facsimile or forgery.

And as soon as that thought hits you, your find your mind back in Vermont, the memory of the experience already fading. But one indelible question remains as you look back on the book in a strange mix of fascination and horror. How on earth would Joseph have been able to make use of these archaic phrases, and to have done so with such consistency?

The Introduction

The Book of Mormon is a strange book, and it only becomes stranger to those who become familiar with the work of Royal Skousen and Stanford Carmack, two of the key scholars involved in the Book of Mormon Critical Text Project, a project which systematically documents the features and differences between all the available editions of the Book of Mormon. In their thorough analysis, they claim to have found strong evidence that much of the English of the book’s translation is not that of Joseph’s time, nor is it of the Bible. It instead contains semantic and syntactic features that best align with those of the 1500s and 1600s, during a linguistic period identified as Early Modern English or EModE. This evidence is difficult to grapple with, not just because of its highly technical nature, but also in terms of its implications. No one knows what it would mean to have authentic, non-biblical sixteenth-century English in the Book of Mormon, but if it really is there, it would place the book far beyond the authorial reach of Joseph or his scribes. Could this evidence be a fluke? Could it be successfully imitated? We turn to Bayes to help with the answer.

The Analysis

The Evidence

Skousen and Carmack lay out their evidence in an exceedingly thorough fashion, whether in a number of articles, in a set of presentations available on YouTube, or in hundreds of pages of reference volumes. The articles are not for the faint of heart, and I’ll admit that technical nuances of Carmack’s linguistic analysis are beyond me. I believe, however, that I’m able to understand the broad strokes well enough. According to them, the Book of Mormon displays deep syntactic patterns that match the sixteenth century and are a poor fit for either the English of the King James or for eighteenth- and nineteenth-century imitations of biblical style. They also assert that the book contains unusual word meanings and phrasing that are completely unattested in either Joseph’s time or in the eighteenth century, yet can be commonly found in the centuries before that time. These two connections to EModE provide independent evidence that Joseph was not the author of the Book of Mormon.

In terms of syntax, Carmack identifies nine key syntactic features that characterize EModE, comparing the frequency of their use in the Book of Mormon, in the Bible, and in four important nineteenth-century works that critics have alleged were sources for Joseph’s writing: The First Book of the American Chronicles of the Times, The American Revolution, The First Book of Napoleon, and The Late War. These latter works each consciously imitate a biblical style, providing good comparison cases for the claim that Joseph imitated King James English when writing the Book of Mormon. (Carmack has since expanded his corpus to 25 pseudo-biblical works, and the features in these support the overall narrative on display here.) Each of these syntactic features represent deep and subtle usage patterns that would be difficult to consciously imitate over the course of a novel-length work. They include such syntax as whether the work prefers using agentive of vs. by, the use of periphrastic did, frequencies of personal which, that, and whom, and the use of finite vs. infinitive verb complementation. Carmack finds that the four eighteenth- and nineteenth-century works are very similar in the relative lack of archaic features, and that these features are also not frequently found in the King James. They are, however, extremely common in the early manuscripts and the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon. Joseph, himself uncomfortable with this syntax, would remove many of these characteristics for the 1837 edition.

In fact, we have at least one good example of Joseph trying to emulate biblical style. Joseph Smith’s personal history is just such an attempt, and gives us a small window into what it would be like for Joseph to attempt to emulate biblical grammar. As Carmack notes, Joseph’s efforts lack these syntactic EModE features.

Skousen and Carmack also identify at least 26 semantic use cases which can’t be found anywhere in nineteenth-century literature and are also completely absent from the Bible. All of these cases are attested in literary and academic literature in EModE. They include the use of “depart” to mean "divide" (changed in our current version to “parted”), the use of “mar” to mean "hinder or stop," and the use of the phrase “but if” to mean "unless."

It’s important to note, however, that these archaic features do not make the Book of Mormon purely a product of the early modern period. There are a number of Hebraic grammatical and poetic features that are far more ancient than EModE. There are also many other sixteenth-century features of syntax and spelling that are missing from the text. Whatever is going on, the text of the Book of Mormon remained generally readable by nineteenth-century audiences.

The Hypotheses

Here are the two hypotheses we’ll consider:

The Book of Mormon was not written by Joseph or his contemporaries—This hypothesis is broad, but it has to be. What little we know about the translation process doesn’t let us say much about how the words themselves were translated into English. But there are a couple things that would be required here to be consistent with the Early Modern English evidence. The first is that Joseph is not involved in producing the wording of the text, or at least any of the words that involve EModE syntax or word meanings (which, when you get down to it, covers a very large proportion of the book). The second is that the text is not actually a true Early Modern English text. Regardless of how the text was produced, the hypothesis is that it’s been filtered or managed in some way so that the words and spellings themselves would remain recognizable to nineteenth-century readers. This would explain how the underlying syntactic structure of the text could show EModE forms, and how many recognizable words could have truly archaic meanings, while sparing us the true strangeness of EModE.

Early Modern English syntax in the Book of Mormon also happens to carry some strange implications about who and how the translation of the Book of Mormon was produced. None of these explanations are likely to make us comfortable, but that sort of speculation doesn’t matter for our purposes here. (Mathematical analysis, after all, doesn’t care whether we are comfortable or not.) All we’re concerned with is that the book didn’t come from the mind of Joseph or his scribes.

The Book of Mormon was written by Joseph using an imitation of Biblical style—According to this theory, any ancient grammatical forms in the Book of Mormon can be explained by Joseph’s (imperfect) imitation of biblical style. It doesn’t matter much whether this imitation was intentional or was merely a reflection of how steeped Joseph and others in the nineteenth-century were in biblical language—the result should be fairly similar. By this theory, Joseph’s grammar should line up well with those of others in his era who imitated biblical style, or should line up well with the Bible itself, and any deviations from those tendencies would be essentially due to chance—that Joseph’s way of imitating biblical forms happened to deviate from those used by others.

This could be framed as two separate hypotheses, but I think it works better as one. It’s not as if Joseph is copying either the Bible directly or the language of his contemporaries—it’s that he’s imitating the style and just happening to match (or not match) either of those sources. We’ll consider how it aligns with both and give critics the benefit of the doubt by using the more likely option.

Prior Probabilities

With those hypotheses in hand, we can take a look at our prior probabilities:

PH—Prior Probability of Non-Joseph Authorship—So far, the probability of an authentic Book of Mormon has increased overall, but in the grand scheme it hasn’t moved all that far from where we initially started. Based on our estimates up to this point, the probability of a non-Joseph authored Book of Mormon stands at p = 1.97 x 10-30. Here’s where we’ve been thus far:

PA—Prior Probability of Joseph as Author—That would leave the remainder for our alternative hypothesis, meaning our prior would be p = 1 – 1.97 x 10-30.

Consequent Probabilities

CH—Consequent Probability of Non-Joseph Authorship—In part because of how vague we’ve made the hypothesis, it would be really hard to say that the evidence under examination doesn’t fit the theory of authenticity. But that vagueness doesn’t do much to alleviate the raw strangeness that this hypothesis seems to exude, at least at first glance. For whatever reason, it’s easier for us to imagine God providing a metaphysically perfect translation that placed the Book of Mormon in the exact linguistic environment of its 19th century readers, or for Joseph to have rendered the ideas of the book directly into his own speech. When we get down to it, though, those are just assumptions we bring to the text as modern (and often implicitly mystical) readers. Gods ways are not our ways–we should be open to translation mechanisms that don’t fit whatever preconceptions we’ve held in the past, instead allowing the text itself to inform our beliefs about how it came to be.

Though the use of Early Modern English isn’t the only way we could’ve gotten an authentic Book of Mormon, I submit that, given how little we know about how the book was ultimately translated, we’d be as likely to end up with that rendering as any other. In fact, just to emphasize that point, I’m going to be assigning a consequent probability of p = 1 for this hypothesis, a value that reflects the idea that there’s nothing the least bit strange about the presence of EModE in an authentic Book of Mormon text. I imagine critics (and maybe some faithful scholars) will cry foul at such a move, but with the amount of a fortiori stretching I end up doing in their behalf later on, I think I’ll be able to live with the guilt.

There’s another point worth discussing here, and it’s how the linguistic features of the text compare to other Early Modern English works. Carmack has worked hard to provide examples of Early Modern texts that show the archaic features he highlights, but I don’t believe he’s conducted the sort of frequency analysis for non-biblical 16th and 17th century texts that he’s done for 19th century ones. It’s possible that the frequency of the Book of Mormon’s archaic features would be considered too archaic, even for the Early Modern period. If so, we would have to adjust this consequent probability. Until we get better data on that front, though, I’ll be content for my substantial a fortiori efforts to make up for that possibility. (And, as we’ll soon see, this consequent probability could be as low as p = .0005 and it still wouldn’t alter my overall evidence score.)

CA—Consequent Probability of Joseph as Author—So how unexpected is the presence of EModE under the assumption that Joseph is the author? Thankfully Skousen and Carmack give us all the information we need to produce a decent estimate. We’ll consider the two main types of evidence separately, looking at the syntactic evidence first, followed by the semantic.

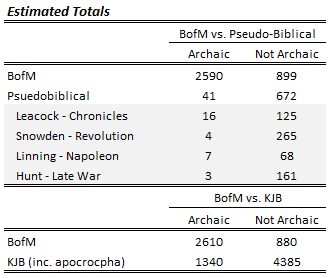

Syntactic evidence. Carmack’s article comparing syntactic patterns between the Book of Mormon, the King James Bible (1611; KJB), and the four pseudo-biblical works provides plenty of quantitative fodder for this analysis. He conducted relatively comprehensive searches of these texts using WordCruncher, providing frequencies or frequency percentages for each of the nine syntactic features and for each class of work—what he doesn’t report directly I was generally able to estimate based on other clues in the article, generally by assuming that opportunities for those features to appear (e.g., a choice between agentic by vs. of) occurred at the same rate per million words in the Book of Mormon, the Bible, and the pseudo-biblical works. You can see how those ended up in the table below, with cells containing my estimates shaded in orange.

For many of the syntactic features he discusses, Carmack is able to report the number or proportion of times that the feature either aligns with archaic EModE usage or whether it follows more biblical patterns. A good example of this is the case of finite vs. infinitive verb usage, where finite verbs (e.g., “causing that they should” vs. “causing them”) are more common in EModE and infinite verb use is more common in modern contexts. That type of reporting is great for a chi-square analysis. What are less amenable to that type of analysis are features that don’t have an alternative form, and that exist only rarely in modern or biblical contexts, like the plural form of -th (e.g., “Nephi’s brethren rebelleth” from the original heading of 1 Nephi). It would be possible to get probabilities for that kind of evidence—we’re going to do something similar for the semantic type of evidence later on—but trying to mix the two types of evidence would get tricky. Leaving out the four features that fall in that latter category (lest-shall usage, more-part usage, had (been) spake usage, and the -th plural) will be one way that we cut the critics some serious slack.

What I did for the remaining evidence was categorize the different forms of each feature as either EModE or as a better match for biblical or pseudo-biblical usage. I then summed the frequency with which archaic and non-archaic forms appear in the Book of Mormon, the King James, and in each of the four pseudo-biblical works, and used that as the basis for the chi-square analysis. You can see those frequencies in the table below.

Note: Values for the BoM differ slightly for the two comparisons, as there is one syntactic feature for which a lower frequency indicates archaic usage relative to the Bible. The frequency counts for that feature were reversed in the comparison with the KJV.

The chi-square values in each case are pretty astronomical; χ2(1) = 1186 for pseudo-biblical; 2337 for the King James (note that the values in the parentheses when reporting chi-square values represent the degrees of freedom for the test); that leaves us with probabilities so small that they have negative exponents in the hundreds (p = 6.46 x 10-260 and 5.35 x 10-510). If we lined up all the particles in the universe (of which there are about 1080), treated each particle like a lottery ball, and then had to correctly select the right ball, we would have to pick the correct one at least 3 times in a row to get a similarly improbable outcome. Clearly, we can be confident that the differences in syntactic usage in the Book of Mormon don’t differ from the Bible or the pseudo-biblical works on the basis of chance. It just so happens that the probability for the pseudo-biblical works is somewhat higher (because it has a smaller sample size overall), so for the critics’ sake we’ll ignore the comparison with the King James.

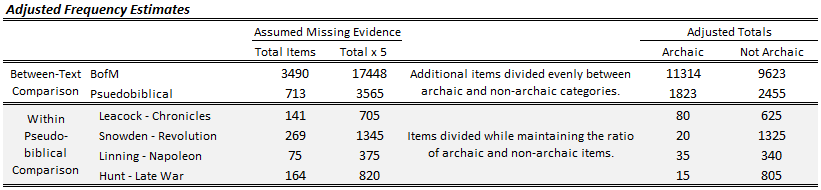

But leaving things there hardly seems fair. After all, maybe Carmack is being selective in his choice of evidence. How about we assume that there’s a ton of evidence within the Book of Mormon that he missed, or that he saw and isn’t reporting on, evidence that contradicts his conclusion. To that end, I assumed that our sample of syntactic examples, for both the Book of Mormon and the pseudo-biblical texts, was magically increased by a factor of five. We’ll use these extra syntactic items as a proxy for our missing evidence.

Now, there are a few ways we could handle (read: manipulate) that evidence so that it “contradicts” Carmack’s conclusion. We could, for example, assume that all of those additional items are non-archaic in both cases. It turns out, though, that the way to best water down the chi-square test (and thus help the critics’ case) is to have half of the additional items be archaic and half be non-archaic. You can see that represented below:

That assumption would probably never hold (see, for example, all the features we already excluded from our analysis), but in this case I’m willing to yield an unreasonable amount of ground to the critics, just to see what might happen. In that case, if we run the chi-square, we get a considerably higher (though still extremely small) probability at χ2(1) = 186, p = 2.63 x 10-42.

Also, chi-square analyses are notoriously sensitive. Once you get sample sizes this high, almost any difference is bound to be statistically significant. One way we can get around that is to adjust our results based on how different the four pseudo-biblical works are from each other. It’ll help if we continue with our assumption that there are a ton of other syntactic features to explore in these works, so I multiplied the number of both archaic and non-archaic items for those works by five (keeping the ratio of archaic to non-archaic items the same). If those works showed extremely large statistical differences, then that would undercut Carmack’s argument considerably. Sure enough, if you do the chi-square test comparing those four works, you get a highly significant result at χ2(3) = 135.7, p = 3.19 x 10-29.

But even though 29 and 42 seem like similar numbers, those probabilities are very different from each other—the differences between the Book of Mormon and the pseudo-biblical works would still be quadrillions of times less likely to occur by chance than the differences between the pseudo-biblical works themselves. Adjusting for the differences we might expect between the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century pseudo-biblical works, the probability of seeing EModE patterns even one fifth as pronounced as the ones Carmack found would be p = 8.24 x 10-14. We’re playing it incredibly safe with this estimate, but that’s the probability we’ll use for the syntactic portion of the evidence.

Semantic evidence. We turn now to the semantic evidence—the archaic meanings contained in the text. As noted above, Carmack and Skousen identify many different examples of archaic word meanings in the Book of Mormon (at least 26, for our purposes) that cannot be attested in either biblical or modern works. It’s safe to presume that that sort of thing would be pretty rare in nineteenth-century works—it’s not likely that many authors would consciously use words in ways that they aren’t familiar with and that their audience is unlikely to understand. You would essentially be using a word in a way that no one else in your century has used it, and in a manner that happens to match how it was used in the past. Hard to do unless you’re steeped in and consciously trying to imitate that specific literature, which neither Joseph nor his scribes would’ve done or had a reason to do.

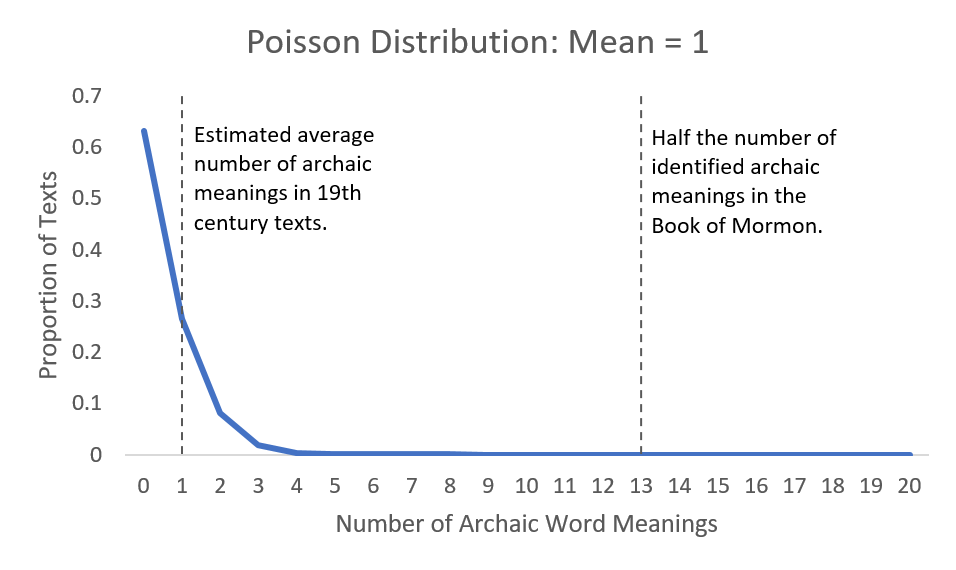

Thankfully, we have ways of estimating the probability of rare events. There are a number of probability distributions that are used to model those sorts of relatively rare phenomena. In this case, we’ll assume that the frequency of unattested archaic word meanings would follow a Poisson distribution similar to how other relatively rare events (such as suicide and criminal acts) tend to function in the real world. If we know, or can reasonably guess, the average number of times that a rare event is likely to occur, we can use that distribution to estimate the probability of that event occurring a certain number of times (or more). The question, for us, is how often we would expect an archaic meaning to show up in an early nineteenth-century work. That sort of thing could be estimated by someone with the necessary expertise, access to solid databases, and a lot of time on their hands (like, say, Stanford Carmack), but for the moment we’ll have to pick the highest value that seems reasonable—for the benefit of the critics, of course. In a work the size of the Book of Mormon, I’d imagine the average number of unique archaic meanings would be at most 1.

But let’s assume, for the sake of argument, that Carmack and Skousen are wrong. Let’s say that, despite all their additional searching and revision efforts, their search remains incomplete, and that fully half of the 26 examples aren’t as archaic as they think. That would leave 13 valid examples of what should be a relatively rare occurrence. Even then, the probability of seeing that many examples of archaic word meaning, as calculated using this online calculator, would be p = 6.36 x 10-11. You can see what that looks like below:

Summary. Taken together, the syntactic and semantic evidence of EModE provide two strong, independent lines of evidence against Joseph authoring the Book of Mormon. The probability of seeing both kinds of evidence by chance would be the product of their respective probabilities, or p = 5.24 x 10-24.

Posterior Probability

PH = Prior Probability of the Hypothesis (our prior estimate of the likelihood of an authentic Book of Mormon, based on prior evidence, or p = 1.97 x 10-30)

CH = Consequent Probability of the Hypothesis (the likelihood of observing the evidence given a non-Joseph authored Book of Mormon, or p = 1)

PA = Prior Probability of the Alternate Hypothesis (our prior estimate of the likelihood of a Joseph-authored Book of Mormon, or p = 1 – 1.97 x 10-30)

CA = Consequent Probability of the Alternate Hypothesis (the likelihood of observing the evidence given a 19th century author of the Book of Mormon, or p = 5.24 x 10-24)

PostProb = Posterior Probability (our new estimate of the probability of an authentic Book of Mormon)

| PH = 1.97 x 10-30 | |

| PostProb = | PH * CH |

| (PH * CH) + (PA * CA) | |

| PostProb = | (1.97 x 10-30 * 1) |

| ((1.97 x 10-30) * 1) + ((1 – 1.97 x 10-30) * 5.24 x 10-24) | |

| PostProb = | 7.96 x 10-5 |

Lmag = Likelihood Magnitude (an estimate of the number of orders of magnitude that the probability will shift, due to the evidence)

Lmag = log10(CH/CA)

Lmag = log10(1/5.24 x 10-24)

Lmag = log10(1.91 x 1023)

Lmag = 23

Conclusion

It looks like we have our first critical strike in the Book of Mormon’s favor, a piece of evidence that meets the statistical bar set by critics for belief in the unusual and the supernatural. Of course, critics would likely beg to differ on that front—evidence against nineteenth-century authorship isn’t evidence of ancient authorship, particularly when that evidence points to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. But without a clearly articulated theory that explains the source of this evidence, critics should rightly take pause. This should especially be the case given how hard we stomped on the scale in favor of the critics. Theories that don’t rely on Joseph’s authorship of the book are greatly strengthened by the presence of Early Modern English, including the theory of authenticity.

This evidence also gets us much, much closer to an authentic Book of Mormon, in conjunction with the other evidence we’ve considered. We’re not there yet; we haven’t tipped the scale from disbelief to belief—and that kind of tipping isn’t necessarily inevitable at this point. But evidence as apparently strong as this should motivate further investigation. No matter is ever truly closed for the honest skeptic, and we should remain open to evidence that could effectively counter what we’ve discussed here, as well as evidence that could further support it. Yet with this evidence is the promise that we’ve just uncovered a minor peak of a mountain of transcendent truth, one whose slope may have just gotten a whole lot steeper. One can’t help but wonder if critics are up for the climb.

Skeptic’s Corner

When it comes to exercising skepticism in this case, the first realistic step is probably to try and redo this analysis with a more complete set of linguistic features, using hard frequency counts instead of estimates, using Carmack’s full set of 25 pseudo-biblical texts, and trying to get a sense of how rare semantic archaisms actually are in modern texts.

After that, though? I’m not gonna lie; I have tremendous pity for critics trying to demonstrate the weakness of this particular class of evidence. The skeptical responses I’ve seen so far have done little more than handwave without meaningfully grappling with the full scope of the evidence. The only path that I see to negating EModE is to produce even more thorough and rigorous work than what’s already been done in this space. However, working harder, longer, and better than the combined efforts of Royal Skousen and Stan Carmack would probably be fatal to most mortals. Keep in mind, too, that this work is ongoing, and in the year or so since I first drafted this essay the corpus of evidence in favor of EModE in the Book of Mormon has only expanded.

But if there are any chinks in the heavy dragonplate of the EModE armor, they’re as follows. The EModE hypothesis is not particularly concrete—we have a much better sense of what the translation process didn’t look like than we do of how it actually worked. The current best contenders—such as an early-modern post-mortal translation committee—sound just as strange as positing the existence of angels and gold plates, and they give us little sense of what we’d actually expect the Book of Mormon to look like if the hypothesis was true. We don’t have many examples where a text has been: 1) translated from an ancient language into Early Modern English translations and 2) has had its spelling and word use largely edited to make it more comfortable for nineteenth-century eyes and ears. It’s a small enough niche that there’s probably nothing to which we can meaningfully compare the Book of Mormon to see if the syntactic and semantic patterns match. Should an army of critics track down a sizable corpus of such material, and it turned out not to look much like the Book of Mormon, that would substantially weaken the EModE position.

We also have quite a few people, including faithful scholars, who remain opposed to the logical implications of EModE. The traditional crux of those arguments is the presence of purported bad grammar in the text, grammar which is attributed to Joseph’s backcountry upbringing. The issue here is that nearly all of the purported “bad grammar” in the Book of Mormon is explainable as mainstream EModE usage, and comparatively little of its EModE is usefully accounted for by frontier American grammar, at least not in the proportions we see in the Book of Mormon. What’s more, the vast majority of the EModE syntax hasn’t been found in any of Joseph’s other writings. Finding further EModE features within frontier dialects or within the (somehow) unexamined writings of Joseph Smith would certainly weaken Skousen and Carmack’s argument. Just don’t be surprised if those efforts are as successful as a duck flapping its way to the moon.

Next Time, in Episode 10:

When next we meet, we’ll have our skeptic re-examine his 1769 King James Bible, to see how likely it would be to have an ancient book rely on a modern translation of yet another ancient text.

Questions, ideas, and arcane secrets can be quietly deposited within BayesianBoM@gmail.com or submitted as comments below.

Oh my gosh, I wish I were a statistician, a linguist and a mathematician combined! From what little I can comprehend as a neophyte, Kyler punches the ball out of the park in a homerun and those who are naysayers can’t believe the audacity of him doing so. For the record, these same naysayers cannot produce their own analysis, they can’t logically refute Kyler’s evidence, and they can’t produce “real” reasons why the Book of Mormon obviously contains Early eModE, Middle eModE and Later eModE except that they strain beyond all sensible, logical and rational reasons. I hate to say it, but from my perspective, their comments border on gobbledy-gook bordering on insanity or perhaps just insecurity or desperation.

Really, after everything is said and done, it comes down to Bruce Dale’s two-part hypothesis as to where these naysayers are leaning, exactly what they are extrapolating and exactly how they think it was all successfully culminated: 1) 1800-era scholars writing in eModE language for who knows what reason… (wouldn’t be discovered until after the year 2000.) and 2) Some brilliant scholar authoring it dozens if not a hundred years before carefully preserving it until it fell into Joseph’s hands. Both scenarios extremely illogical, but truly, that’s all they’re left with.

As a final aside, and for the record, I typically enjoy Brandt’s unique perspective and take on things, but in this one instance I believe that he went way beyond his expertise and his duty as moderator. In this particular instance, he actually muddied the waters and did not contribute significantly to the conversation. This was a big boo-boo Brandt, unnecessary, and not really incidental to Kyler’s presentation.

Tim, I don’t mean to muddy the waters, but we really do need to be careful about what we claim as evidence of antiquity. In the case of Early Modern English, it says absolutely nothing about antiquity. There is a claim that there was an ancient text that was translated into English, and the Early Modern English evidence suggests when–but says nothing about the underlying text itself.

There is, of course, the argument that Joseph couldn’t have done it–but then Skousen and Carmack don’t think he did. Someone else did. Whoever it was created an English text, and just having an English text doesn’t mean anything about antiquity. There have been other proposals that the someone else wrote the Book of Mormon (see the Spaulding arguments). None of those have been able to be a source, but an argument that simply says someone else wrote the Book of Mormon doesn’t demonstrate antiquity. I know it is intended to demonstrate that it was divinely inspired, but that only works if one accepts it as ancient.

I fully support an ancient underlying text, but that underlying text is not demonstrated by anything in English. It is either a translation or an invention, but the English alone cannot tell us which it is.

Sorry Brandt, didn’t mean to imply that you were using the phrase, “eModE doesn’t prove antiquity,” except that it originally came from Billy Shears. Also, due to that, I wasn’t implying that you were oxymoronic in any way. My apologies if that appeared to be the case.

My issue is that having read through the comments, I could not locate (and possibly because I was reading relatively rapidly) where anyone, except Billy, had made that particular assertion.

If the comments were aligned in such a manner that I could tell through formatting who had made the claim, then perhaps I would not have felt that your comments only furthered in “muddying the waters.”

Also, it seemed in your response to me that you were focused on “antiquity” when in reality from my observation of the comments, none of us were attempting at that point in time with equating eModE with a proof of antiquity and so it seemed to me that you really weren’t understanding my gripe against your initial comment.

Once again, sorry for any aspersions on your ability. We all know that you have a large understanding of Book of Mormon issues.

Thanks for your comments Tim. I strongly believe, though, that thoughtful, good faith arguments can never muddy the waters. Brant makes a valid point, and I’m glad he spoke his mind.

Thank you for the response Kyler (great series by the way!) But, here’s the deal. Part of the issue that I have with Brandt’s response is that we aren’t really clear by the formatting provided exactly who Brandt was responding to or against. The ONLY thing we know (those of us reading later on) based on Brandt’s response alone, is that Brandt agreed with Billy Shears that eModE doesn’t prove antiquity.

Now for the gyst of my problem and I know I’m not going to do a good job explaining, but I am going to try:

I don’t believe there are ANY of us (Book of Mormon believers / we who disagree with Billy Shears for instance) who would nevertheless ever argue that eModE proves antiquity of the Book of Mormon. In itself the two terms together form an oxymoron, because the era of eModE stretches somewhat on either side of the middle of the millenium (1500 plus and minus.) So for me, the oxymoron is that I would never consider the 1500’s as being “antiquity.” For me, antiquity is Old Testament and probably the New Testament and 600 BC for Nephi, but in terms of real antiquity, nothing short of 5 or 600 years make its way into real “antiquity.”

Thus, Brandt’s argument agreed with Billy for no purpose that I can see or discern in that no one on our side of the fence would have been making that particular argument. (i.e. that eModE “proved” antiquity.) For me, it’s an oxymoron to describe the eModE era with “antiquity,” and I just don’t see any reasonable person making that type of analogy. If someone attempted to actually do that, then please refer me back to their comment, because I most certainly missed it. In other words, for me, Brandt muddied the waters.

Sorry if my issue doesn’t make sense. I did the best I could.

Kyler,

Thank you for another great post. The Poisson model for the semantic evidence is simple and compelling. You use 26, but my understanding is that the current count of archaic non-Biblical semantic usage in the Book of Mormon is 49 (https://interpreterfoundation.org/blog-pre-print-of-revisions-in-the-analysis-of-archaic-expressions-in-the-book-of-mormon/), and the upper cumulative distribution at x=49 for a Poisson distribution with mean 1 is 6.17×10-64!

Oliver Cowdery, David Whitmer, and Martin Harris testified that the Book of Mormon was translated from “plates which contain this record, which is a record of the people of Nephi, and also of the Lamanites . . . by the gift and power of God.” Those who have been unable to accept this explanation have devised many alternate theories for the origin of the Book of Mormon (recently summarized at https://byustudies.byu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/58-3halessecured.pdf). The primary theories include a) the Solomon Spaulding theory, b) contemporary collaborators, c) mental illness, d) automatic writing, and e) Joseph’s intellect.

If it holds, the evidence of archaic, non-Biblical early modern English in the Book of Mormon makes highly improbable all of the standard naturalistic explanations for the book. Other theories that account for the archaic language would need to be developed. Perhaps a future extension of your Bayesian analysis could treat seperately each theory.

I take the discovery of the archaic language in the Boof of Mormon as a wonderful sign and miracle. Here is a good article by my high-school seminary teacher on the purposes of signs and miracles: https://abn.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/ensign/1994/12/i-have-a-question/i-have-a-question?lang=eng.

Rasmussen says (Sept 2, 8:53pm) that “to argue for a 16th century origin …would” move “the nature of that origin outside the reach of academic inquiry. We can speculate, but we’ll never know, and thankfully we don’t need to know.”

That seems quite untrue and even nihilistic, and there are scholars currently exploring the origin of the Book of Mormon as created by a scholar of the early modern English period who bases his work on actual SE Asian history and legend.

There are far more substantive and scientific ways to take the measure of the BofM than this particular approach.

Robert:

From Merriam-Webster, here is the definition of nihilism:

1a: a viewpoint that traditional values and beliefs are unfounded and that existence is senseless and useless

Nihilism is a condition in which all ultimate values lose their value.— Ronald H. Nash

b: a doctrine that denies any objective ground of truth and especially of moral truths

Can we please agree that it was at best inaccurate to refer to Tyler’s comment as nihilistic? (At worst, it was an ad hominem attack.) Where does Tyler assert that traditional values and beliefs are unfounded, or that existence is senseless or useless? He does no such thing.

I believe it is not “nihilistic” to suggest, as Kyler does, that some subjects are “outside the reach of academic inquiry”. Perhaps he might have more accurately stated it as “outside the reach of fruitful academic inquiry”.

Academics can and do speculate endlessly on subjects for which there is simply no evidence that will allow them to test their speculations. That is fruitless academic speculation, not productive academic inquiry that will develop testable knowledge or new insights.

I am a lifelong academic, and there are many subjects that are indeed outside the reach of fruitful academic inquiry because they are subjects about which we cannot test our conclusions…we do not have the data/evidence. (Of course, these are great areas for unbridled speculation, because our speculations cannot be tested and therefore we cannot be held responsible for our speculative conclusions.)

As to your comment that “far more substantive and scientific ways to take the measure of the Book of Mormon than this particular approach”, I wish to disagree strongly.

The supposedly “scientific” approaches that I have seen taken in the past do not consider evidence both for and against the Book of Mormon’s authenticity. Invariably, they only consider negative evidence.

That is simply not the scientific way to test hypotheses.

It is greatly to Kyler’s credit that he is considering a range of evidence, both for and against the Book of Mormon and that he is using the Bayesian approach to do so.

Bruce

Thanks for your thoughts, Robert. Once the exploration you mention is complete, I’d be very interested in taking a look.

i think i put this in the wrong place, so i’ll try again:

Rasmussen: “Summary. Taken together, the syntactic and semantic evidence of EModE provide two strong, independent lines of evidence against Joseph authoring the Book of Mormon. The probability of seeing both kinds of evidence by chance would be the product of their respective probabilities, or p = 5.24 x 10-24.”

Kyle, why do you consider finding EmodE syntax and EmodE semantic evidence in a text to be “strong, independent lines of evidence”?

why would those two things be independent, in an EModE text?

Rasmussen is correct to suggest that EModE in the BofM is as likely to be evidence of modern fiction as it is of inexplicable transmission through a very naive Joseph Smith.

As to the “judgment bar” of Christ (or Royal Skousen’s conjectural “pleading bar of God”), we may very well have ancient Egyptian wording there: Since Egyptian mdw “staff, rod” (= Hebrew maṭṭē “rod, staff”) is a homonym or homograph of Egyptian mdw “word; speech,” and is also regularly used as part of the phrase mdw ntr “word of God, divine decree; sacred writings (hieroglyphic or hieratic); written characters, script,” Matt Bowen has long since rightly concluded that “the rod of iron” is correctly interpreted in the Book of Mormon as “the word of God”(1 Nephi 11:25, 15:23-24). Aside from the brilliant word-play, that same Egyptian mdw “staff, rod,” is also used in the legal phrases mdw ḥr/m “to litigate (lit. to speak about something),” and šm r mdwt ḥnˁ “to go to court with someone (lit. to go in order to talk with someone)” (Instruction for the Vizier R 27). It is thus possible to read mdw ntr “word of God” simultaneously as “the judgment-bar, the pleading-bar of God.”

This likewise fits the concept of the Lord being “a staff to the righteous” in 1 Enoch 48:4, which is part of a pericope dealing with “the fountain of righteousness” (48:1). The word “bar” stands alone with that same meaning in 2 Nephi 33:11, and Jacob 6:13, “which bar striketh the wicked with awful fear and dread,” etc.

Rasmussen:”Summary. Taken together, the syntactic and semantic evidence of EModE provide two strong, independent lines of evidence against Joseph authoring the Book of Mormon. The probability of seeing both kinds of evidence by chance would be the product of their respective probabilities, or p = 5.24 x 10-24.”

why do you consider finding EmodE syntax and EmodE semantic evidence in a text to be “strong, independent lines of evidence”?

Thanks Lynn. That’s a good question.

In short, the independence on those factors depends on the hypothesis we’re using. If you, like Billy, happen to be entertaining a hypothesis of 16th century origin, then syntax and semantics wouldn’t be independent–they’d both be closely intercorrelated aspects of the language as spoken by those in the Early Modern period.

However, for the hypothesis of 19th century fraud, those two things would be independent. If one was trying to imitate biblical style, it might be possible (though incredibly unlikely) to end up with a syntactic style that appeared to be truly archaic. But in doing so you would not be any more likely to pick up the extinct archaic word meanings found in the BofM. The same applied to the reverse scenario. Using words in ways that happened to be extinct and archaic, as rare as that would be, wouldn’t provide you with the ability to execute archaic syntax.

Now, there’s another hypothesis where those items wouldn’t be independent, and that’s a hypothesis that had Joseph consciously imitating–not biblical style–but the direct style and semantic choices of EModE. Assuming that Joseph would be capable of such a thing, and would have a reason to do it (both of which I see as unlikely enough that they weren’t considered here), then those items would also not be independent.

Hypotheses matter folks!

“ In short, the independence on those factors depends on the hypothesis we’re using. If you, like Billy, happen to be entertaining a hypothesis of 16th century origin, then syntax and semantics wouldn’t be independent–they’d both be closely intercorrelated aspects of the language as spoken by those in the Early Modern period.

However, for the hypothesis of 19th century fraud, those two things would be independent.”

You are incorrect. These two elements are both EModE elements of EModE text which inherently occur together. They are, as pieces of information contained in EModE, NOT independent of each other.

As such, it is irrelevant what hypothesis you are considering when you are evaluating their dependence. You need to consider the elements themselves.

You are presenting them as independent pieces in support of your EModE hypothesis, and that is an error on your part.

Let me try this again, it didn’t seem to work last time:

“ In short, the independence on those factors depends on the hypothesis we’re using. If you, like Billy, happen to be entertaining a hypothesis of 16th century origin, then syntax and semantics wouldn’t be independent–they’d both be closely intercorrelated aspects of the language as spoken by those in the Early Modern period.

However, for the hypothesis of 19th century fraud, those two things would be independent.”

You are incorrect. These two elements are both EModE elements of EModE text which inherently occur together. They are, as pieces of information contained in EModE, NOT independent of each other.

As such, it is irrelevant what hypothesis you are considering when you are evaluating their dependence. You need to consider the elements themselves.

You are presenting them as independent pieces in support of your EModE hypothesis, and that is an error on your part.

For you to present the possibility that the two types of language could not be BOTH imitated is an assumption on your part that you want to treat as factual, in order to argue independence.

Imposing your imagined possibilities as factual within the context of analysis is not appropriate statistical technique.

Has any Latter-day Saint scholar put forward a plausible explanation for the appearance of Early Modern English in the original text of the Book of Mormon?

Is it possible that after the first set of translation tools given to Joseph Smith (the instruments prepared by Moroni) were rescinded, a more efficient set of translation tools and translation methodology was required?

The urim and thummin, with stones, bow and breastplate allowed Joseph to translate by a direct reading of the inscribed characters. However, through disobedience, Joseph forfeited use of those tools along with the first 116 pages of manuscript. Also consider that the physical bulk of the translators may have been too difficult for Joseph to safeguard. Moroni could no longer entrust them to Joseph, and this loss of trust forced Moroni to implement a second translation methodology. Namely, elements easier for Joseph to control, elements which included a seer stone as visual, “text transmitter”, combined with the light-blocking function of a simple top hat, and a prepared manuscript for the prophet to read.

Joseph was no longer required to translate by a direct reading of characters inscribed on metal plates. Instead, as eye witnesses attested, he dictated as if reading from a prepared manuscript. May we infer that it was an English manuscript, perhaps a manuscript prepared by writers who were practitioners fluent in Early Modern English? If so, who prepared the manuscript?

Consider the work of the Lord that has been conducted, and is now on-going in the post mortal world, and consider the preparations that might have been made there to bring forth the Book of Mormon. We are searching for a missing link in the translation process, a link that falls under the category described as “the gift and power of God”.

As at so many other times and circumstances in the history of the world, gospel progress required alternate, or back-up plans. In this case, the plates still had to be translated/transitioned from the original inscribed languages into a text fit to be published as The Book of Mormon. Who better to do the heavy lifting of translation and preparation of an English language manuscript that Joseph read from his seer stone, than a group of select English writers in their post-mortal condition, who operated under the Lord’s direction, and possible tutelage of Moroni, and who predated Joseph in mortality by 200 to 300 years? Writers who wrote using Early Modern English during their mortal lives, that’s who. Is there anyone prepared to ponder this as a possibility?

Eric Pond

Vancouver, Washington, USA

M: 360-838-3687

ericpond@msn.com

Thanks for the comment, Eric. Though I think it would’ve been possible to have the same indirect reading process through the interpreters as through the seer stone, your proposed mechanism of post-mortal translators happens to be the one I favor. Skousen and Carmack have considered and pondered that possibility, but seem to prefer not to speculate on something that’s likely unknowable in the absence of revelation. But I favor it nonetheless.

The responses I hear from critics of that hypothesis is generally that God is able to do his own work, and that positing post-mortal translators somehow lessens the divinity of the book. I disagree. Does calling and guiding prophets somehow mean that God is unable to do his own work? Does delegating responsibility to Elders Quorum presidents or to the Deacons quorum somehow lessen the divinity of the Priesthood of the efficacy of the sacrament? I don’t think it does. And in this case I think we should lean to where the evidence leads us, and the evidence seems to indicate a solid variety of archaic syntax, syntax that can’t be pinpointed to a specific EModE time period. To me, the best explanation for that evidence is contributions from a variety of EModE speakers across several centuries, rather than from a single voice making use of EModE.

We should be open to new evidence, and to alternative ways of accounting for that evidence, but I hope scholars and others remain open to the mechanism you propose here.

Brother Rasmussen,

Thank you for your thoughtful response, and your insightful essay.

Eric Pond

Thank you, Eric and Kyler. This is a fascinating idea…this possibility had never occurred to me. Thanks for giving me this idea to ponder.

I am a convert to the church through the power of the Book of Mormon. My ancestors have been on my case ever since I joined the church almost 55 years ago–and I have helped thousands of them receive their ordinances.

I happen to know that the post-mortal world is real. I know that the coming forth of the Book of Mormon matters a lot to those who live there. It is the converting power of the Book of Mormon that will continue to operate on the living, as it continues to operate on me, to bring those billions of people forth out of their prison.

Thanks again! I will be pondering over this for days.

Bruce

This episode is so flawed I don’t have the space here to respond fully, and it is so fundamentally unserious I feel little motivation to do so.

A big issue to get out of the way is the consequent possibility of p = 1. Yes, I’m going to cry foul on this one. What this means, specifically, is that before Carmack and Skousen started this project, i.e. before the experiment was conducted, you declared that if the Book of Mormon is true, then there would be exactly as much EModE as Skousen and Carmack found. You then ran the experiment and behold! Your hypothesis about EModE was precisely confirmed!

This is the most dramatic example of the Texas Sharpshooter fallacy I could imagine. The truth is you drew these tiny targets around the holes in the side of the barn after the bullets hit the barn, not before. That is why they are hits.

In Royal Skousen’s own words, “we should be cautious and less judgmental and recognize that the nonstandard English of the original Book of Mormon text could be Early Modern English rather than simply Joseph Smith’s dialectal usage.” (BYU Studies Quarterly no. 3, 2018). It’s ironic how you take his exoneration to be cautious as license to throw caution to the wind and declare bad grammar proves the book is ancient.

In my parallel analysis, I’m trying to consistently address a single question: is the Book of Mormon an accurate translation of an authentic ancient Mesoamerican manuscript? When going down this EModE rabbit hole, Skousen says things like, “there are numerous issues which show that the Book of Mormon is concerned with what the Protestants dealt with and argued over during the 1500s and 1600s… Given all of these similarities with Reformed Protestant issues of the 1500s and 1600s, it is not surprising then that the Book of Mormon resonates so well with a number of Protestants coming from the Radical Protestant tradition.” (ibid.)

He also says, “Is the Book of Mormon English translation a literal translation of what was on the plates? It appears once more that the answer is no. The blending in of specific King James phraseology, from the New Testament as well as the Old Testament, tells us otherwise. The Book of Mormon is a creative translation that involves considerable intervention by the translator (or shall we say translators, since we’re in a speculative mood). There is also evidence that the Book of Mormon is a cultural translation. Consider, for instance, the interesting case of the anachronistic use in the Book of Mormon of the noun bar, which consistently refers to the bar of judgment that we will stand in front of (and hold on to) on the day of judgment. The judgment bar is not a biblical or ancient term, but instead dates from medieval times….” (ibid.)

I personally suspect the real implication of these various words and phrases being in the Book of Mormon is that they were part of Joseph Smith’s vernacular. If I’m wrong about that and they really are definitive proof of a 16th century Book of Mormon that was mostly-retranslated to be intelligible in 1829 then so be it. That just means it is 16th century fiction rather than 19th century fiction. Either way, the fact remains that all of the concern about protestant religious issues (whether they are from the 19th or 16th century) described with European analogies rather than Mesoamerican religious issues described with Mesoamerican analogies supports the hypothesis that the BoM is modern.

Evidence score on this point: -1. Odds against Book of Mormon being authentic: 40,000,000-to-1.

Hi Billy!

“This episode is so flawed I don’t have the space here to respond fully, and it is so fundamentally unserious I feel little motivation to do so.”

Your exasperation is a pretty good indication for me that I’m doing something right.

“What this means, specifically, is that before Carmack and Skousen started this project, i.e. before the experiment was conducted, you declared that if the Book of Mormon is true, then there would be exactly as much EModE as Skousen and Carmack found.”

Yep, that’s what it means. And if the EModE’s critical strike could only be achieved on the basis of the value of that consequent, you’d have an argument on your hands. But that’s not the case. Even here, the value could be as low as .0005 and it would still be a critical strike. If a 1-in-a-million or 1-in-a-quadrillion consequent strikes your fancy, all I’d have to do is assume somewhat fewer missing characteristics or a marginally more reasonable mean for the Poisson, and I’d have a couple dozen more orders of magnitude to play with. In that context, I feel fine using the consequent for rhetorical purposes–in this case, socializing the idea that EModE isn’t necessarily weird from a faithful perspective. We’re probably weird for thinking its weird.

If the math’s unreasonable or inappropriate, please tell me so–I’d be happy to find a better statistical frame here. But if your statistical arguments are limited to “well, maybe things would look different if you had more data”, then that’s not particularly helpful. Maybe it would. Until then, though, I don’t see much else to go on besides my best reasonable guess. And my best guess is that EModE is unexpected as all get-out under the hypothesis of modern fraud.

“It’s ironic how you take his exoneration to be cautious as license to throw caution to the wind and declare bad grammar proves the book is ancient.”

Did I use the word proof anywhere? Did I not heavily emphasize the need for further investigation? Does using extensive a fortiori adjustments not count as caution?

It’s Royal’s job to be cautious about what conclusions can be drawn with the data. It’s my job to use the data we have to produce conservative estimates. Different perspectives that employ different varieties of caution. I’m sure he’d agree with me, though, that the data almost certainly rule out a 19th century origin for the text.

“I personally suspect the real implication of these various words and phrases being in the Book of Mormon is that they were part of Joseph Smith’s vernacular.”

Having spent an inordinate amount of time looking at this evidence, I can tell you that your suspicions are a bad fit for the data. Bad grammar doesn’t account for the lexis. It doesn’t account for a substantial proportion of the syntax. It doesn’t account for our inability to find good examples of almost any of this in Joseph’s own writing.

“That just means it is 16th century fiction rather than 19th century fiction.”

You go ahead and detail a cogent theory for the 16th century origin of the Book of Mormon. Lay out every piece of evidence and argument you can muster. Provide concrete details for how it was written and how it ended up in Joseph’s hands. Promote it as the best hypothesis available. Then tell me whether you feel any less silly than if you’d argued for angels and gold plates. I know I’d feel about as uncomfortable as Neil Degrasse Tyson at a Flat Earth conference.

“Evidence score on this point: -1”

The next time you suggest that I’m ignoring evidence, I’m going to remember this moment. And I’m going to giggle uncontrollably.

Hi Kyler,

I’m deliberately ignoring the bulk of your argument on this point because, and I can’t emphasize this enough, it is a non sequitur. Alleged evidence of a 19th century book being peppered with words, grammar, imagery, and protestant religious issues from 16th century England simply isn’t evidence that the book is an accurate translation of an authentic ancient Mesoamerican manuscript.

Those words, grammar, imagery, and protestant religious issues *might* be evidence that the book was written in the 16th century. Likewise, it *might* be evidence that remnants of those things survived in the language until the early 19th century. Either way, it is not evidence that the book is an accurate translation of an authentic ancient Mesoamerican manuscript.

In fact, it is evidence of the opposite.

You don’t have to be an atheist to see this implication. In the words of Royal Skousen, “Is the Book of Mormon English translation a literal translation of what was on the plates? It appears once more that the answer is no.” (See “The Language of the Original Text of the Book of Mormon” by Royal Skousen in BYU Studies Quarterly, 2018).

Best,

Billy

“I’m deliberately ignoring the bulk of your argument…”

And thus EModE entered Billy’s shelf, doomed to gather dust, the shelf’s proprietor content with his near-complete inability to account for or otherwise address this evidence.

“Is the Book of Mormon English translation a literal translation of what was on the plates? It appears once more that the answer is no.”

And yet, Royal remains firm in his support for both plates and translation, this evidence apparently having become one of many pillars implying that each existed and were authentic.

And when you read my first point above, it’s required that you read it in the voice of the Hades narrator, which you can listen to here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qOT6YMy0j6s

That voice has been in my head all month.

“And when you read my first point above, it’s required that you read it in the voice of the Hades narrator…”

I give you credit for style points, lol.

“And thus EModE entered Billy’s shelf, doomed to gather dust, the shelf’s proprietor content with his near-complete inability to account for or otherwise address this evidence.”

You are equivocating the shelf analogy. Normally, a “shelf” in this context means ignoring evidence that contradicts your faith, with the hope that someday the contradictory evidence will be explainable.

That is not what I am doing.

The details of your EModE argument are a logical non sequitur. The traces of EModE in the BoM *might* prove that the BoM was written in the 16th Century. Or they might be explainable in a 19th Century context. In principal I’m open to either being true. Regardless, this is evidence *against* the BoM being an accurate translation of an authentic ancient document.

Whether I have a “near-complete inability” to detail the assumptions implicit in your statistical models and evaluate the likelihood of them being true is a question the readers will need to decide for themselves. But a serious statistical analysis would have listed the assumptions in the first place, frankly evaluated their probability of being true, and caveated their results on the validity of these assumptions.

“You are equivocating the shelf analogy. Normally, a “shelf” in this context means ignoring evidence that contradicts your faith, with the hope that someday the contradictory evidence will be explainable.

That is not what I am doing.”

So you’re committed to a 16th century origin then? Because otherwise that’s exactly what you’re doing, clinging to the vague hope that someday the “bad grammar” explanation becomes viable.

“Regardless, this is evidence *against* the BoM being an accurate translation of an authentic ancient document.”

Technically it’s the protestant themes which would be evidence against an accurate translation, not the syntax and the lexis, and we’ll get to the themes down the road. The EModE itself would only be evidence that it’s not a direct transliteration (which of course it wouldn’t be), and that it’s not in 19th century vernacular (and is unlikely to have been produced by imitating biblical vernacular).

The latter happen to be a mortal blow to the idea that Joseph or his contemporaries wrote the thing.

Cheers Billy! Last word’s yours.

With all the great research out now, including that posted in these series, the burden of evidence now falls on Billy and his ilk… And they are clearly coming up on the short end of the stick. The data and evidence now available for an authentic B of M are strong and Mr. Rasmussen has presented it using a scientifically congruent approach.

It’s clearly frustrating to have to deal with so much overwhelming evidence. I feel for those who are on the wrong side of the B of M evidence. It truly must be a disheartening endeavor.

Rasmussen: 1. Shears: 0.

Check and mate, I’d say.

The Book of Mormon is either an authentic ancient document, as it claims, or it is a work of fiction, written by one or more people in the early 19th century. There are no other options.

If it is a work of fiction, then those who believe that to be the case have to explain why there is undeniable evidence for EModE in the book, that is, 16th century language in supposed work of fiction written in the early 19th century.

So those in the fiction camp just had their work of explanation made a lot harder…20 orders of magnitude harder sounds about right.

Ouch!

For the record, I support an ancient Book of Mormon (original). However, Billy is correct that the EModE evidence doesn’t point to antiquity. It points to EModE, and asserts that it was written about that time. The question of whether or not it is a translation still exists. The difference is now when it was translated, not whether.

The “Joseph couldn’t do it” argument simply suggests that someone else did. Skousen has not opined on how it happened, only that he agrees that Joseph wasn’t behind the translation. We have exactly the same problem, but moved a hundred years (or less) earlier.

Thanks for the comment Brant. Just a couple points where I’d differ with you a bit.

First, my understanding is that much of the EModE evidence pushes the language back further than your hundred years (or less) scenario. There are pieces as recent as that, but a lot of it can only be found two or three hundred years down the road. I find that variety interesting in itself, but regardless, it’s important to appreciate that scale. It’s not just a matter of a few decades.

Second, strictly speaking, I’d say that EModE doesn’t necessarily denote a timeframe for translation/composition. All it confirms is the language used by whoever it was who did so. From a naturalistic perspective the only way to realistically get those speakers would be to look to that timeframe. From a faithful perspective, our options are somewhat broader.

That’s obviously useful from an apologetic perspective. If critics were forced everywhere and always to argue for a 16th century origin that would dampen the effectiveness of their message considerably. But it’s also frustrating, because it probably moves the nature of that origin outside the reach of academic inquiry. We can speculate, but we’ll never know, and thankfully we don’t need to know.

“You are incorrect. These two elements are both EModE elements of EModE text which inherently occur together.”

They are if you speak EModE. If not, then they’re not.

Here’s an example. Say that you were trying to make a book sound biblical. You’d probably throw in a random mismash of thees and thous and haths. Say that, purely on the basis of chance, that syntax happens to match what you’d see in EModE.

Would that process necessarily produce any extinct lexis? No. Because 1) extinct lexis doesn’t sound old, just unfamiliar, and 2) if a modern speaker is making use of the word, they’d be far more likely to just use the meaning they know, instead of the meaning that’s since become extinct. Thus, in the case of Joseph or anyone else in the 19th century, those two factors are independent.

In my view, the only way that you get both lexis and syntax is to either speak it natively, or to be purposefully trying to emulate (non-biblical) EModE. I don’t see any rhyme or reason that would lead Joseph or anyone else in the 19th century to try to do so, nor would I expect them to be able to pull that feat off.

I don’t expect you’ll agree with me, but hopefully it’s clear enough why I think the independence assumption is valid here.

that is not a valid reason for assuming independence, because you are assuming to be true elements of your hypothesis, which you are supposed to be testing.

you cannot assume your conclusion as a starting condition of your analysis.

Every hypothesis has connecting assumptions, such as assumptions of independence.

As soon as you can demonstrate to me that efforts by a non-speaker to produce syntax will necessarily produce lexis, and/or vice versa, I’ll happily change my tune.

As a corrolary, it’s like saying that any attempt to speak like Yoda will inherently produce word meanings from languages that also use Yoda-like syntax (e.g., Spanish). I don’t expect you’ll be able to demonstrate anything of the sort, but I’ve been wrong before.

“I also don’t understand why you assume that correct lexis automatically includes correct syntax.”

Hi, Bruce. Then you understand perfectly my objection to Rasmussen. He assumes correct lexis automatically DISCLUDES correct syntax.

My point was that you can’t autiomatically assume one comes without the other, OR with the other.

I’m pleased you agree with me that Rasmussen is using bad logic here.

“Hi, Bruce. Then you understand perfectly my objection to Rasmussen. He assumes correct lexis automatically DISCLUDES correct syntax.”

Bruce’s characterization is correct. And you may need to spruce up on your definition of statistical independence.

Hi Lynn,

I think Kyler’s assumption fits with his hypothesis. Under his hypothesis, I think his assumption is reasonable. I would not expect the same writer in the early 19th century to have command of both EModE lexis and syntax.

However, I am not sure what your hypothesis is for the presence of EModE in the Book of Mormon. I stated the two hypotheses under which I could envision simultaneous lexis and syntax in a naturalistic explanation of the Book of Mormon . I cannot think of a third hypothesis that fits a naturalistic explanation.

So I respectfully ask: Which of those two hypotheses do you accept? (Or is there another naturalistic explanation that I am missing?).

Bruce

“Every hypothesis has connecting assumptions, such as assumptions of independence.”

When evaluating evidence, if you take your assumptions as given, you are assuming your conclusion.

KR: “ As soon as you can demonstrate to me that efforts by a non-speaker to produce syntax will necessarily produce lexis, and/or vice versa, I’ll happily change my tune.”

That is further proof that you are assuming your hypothesis is correct, and assuming that your hypothesis is true, and then using it to come to your conclusion.

“When evaluating evidence, if you take your assumptions as given, you are assuming your conclusion.”

If an assumption isn’t given, it’s no longer an assumption.

Google’s definition is useful here:

“a thing that is accepted as true or as certain to happen, without proof”

“That is further proof that you are assuming your hypothesis is correct, and assuming that your hypothesis is true, and then using it to come to your conclusion.”

If my assumption of independence isn’t true that would definitely change my estimates. This is the case with all statistical assumptions. But It could easily have been the case that the assumption of independence is true but that my conclusion was not. One does not follow logically from the other, as you seem to be claiming.

Also, the assumptions I need to make are conditioned bythe hypotheses under consideration. This isn’t some sort of flagrant statistical foul. This is a sign that I’m thinking through the problem in a nuanced way.

All I was asking you do to was demonstrate how my (reasonable) assumption is inaccurate. I’m going to continue to note that you’re not doing so.

Hi Lynn:

I don’t think I understand this comment. Scientists (and scholars) routinely assume hypotheses to be true for the purpose of testing them against the evidence. If you assume a hypothesis to be false, then there is no way (and no need) of testing it. That is standard scientific procedure.

Do I misunderstand your comment? If you meant something else, kindly explain it to me.

I also don’t understand why you assume that correct lexis automatically includes correct syntax. It seems to me that if you assume that whoever wrote the Book of Mormon was able to call forth both the correct syntax and lexis from the 16th century then that means one of two things:

1) An incredibly gifted scholar (or scholars) living in the early 1800s wrote the Book of Mormon and were able to generate both the lexis and syntax of 16th century EModE in a 531 page *fictional* work (the Book of Mormon) that he/they created and published anonymously through Joseph Smith. For what purpose? How was that conspiracy kept quiet? Wow, the questions that must be answered if you make that your hypothesis! Or…

2) Another gifted individual (or individuals) living in the in the 16th century wrote the Book of Mormon and handed it down through the centuries to other individuals who finally hit on the perfect person with whom to fob this book off on the world…a young semi-literate farm hand in rural upstate New York. Again, for what purpose? How was that multi-century conspiracy kept quiet? Double wow! So many (more) questions to answer if you make that your hypothesis.

But it seems to me that you have to accept one of those two hypotheses if you want to get both EModE lexis and syntax together without assuming them to be independent statistically.

Or do you have another explanation? If so, kindly tell me what it is.

Thanks,

Bruce