Intro/FAQ ⎜ Episode 1 ⎜ Episode 2 ⎜ Episode 3 ⎜ Episode 4 ⎜ Episode 5 ⎜ Episode 6 ⎜ Episode 7 ⎜ Episode 8 ⎜ Episode 9 ⎜ Episode 10 ⎜ Episode 11 ⎜ Episode 12 ⎜ Episode 13 ⎜ Episode 14 ⎜ Episode 15 ⎜ Episode 16 ⎜ Episode 17 ⎜ Episode 18 ⎜ Episode 19 ⎜ Episode 20 ⎜ Episode 21 ⎜ Episode 22 ⎜ Episode 23

[Editor’s Note: This is the fifth in a series of 23 essays summarizing and evaluating Book of Mormon-related evidence from a Bayesian statistical perspective. See the FAQ at the end of the introductory episode for details on methodology.]

The TLDR

It seems unlikely that the witnesses to the Book of Mormon could give such bold and straightforward testimony to an apparent fraud, particularly if those witnesses proved true to their testimony as time passed.

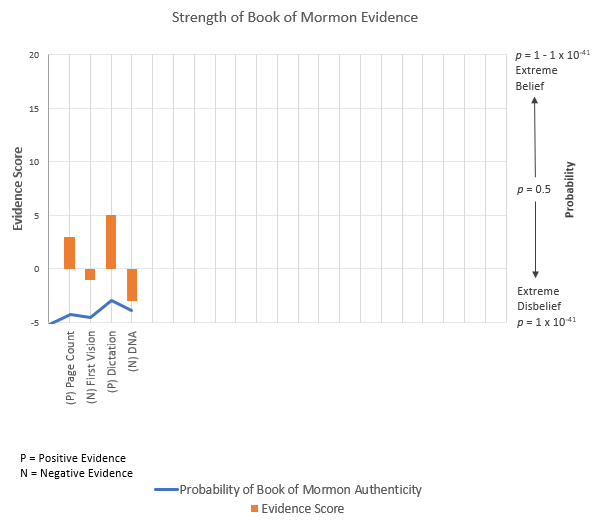

Critics have a fun time using the Book of Mormon witnesses as a rhetorical punching bag, mainly because the witnesses themselves aren’t around to fight back. Nevertheless, the witnesses’ testimony remains persuasive to many, and the Bayesian analyses in this episode appear to bear that out. I examine the two most common arguments used to dismiss the witness’s accounts and conclude that: 1) it’s unlikely that a conspiracy of 11 people could be maintained in the face of severe persecution and personal animus toward Joseph Smith (p = 2.69 x 10-8), and 2) it’s nearly as unlikely that Joseph could’ve deceived the witnesses through hypnotic suggestion and a false set of plates (p = 3.68 x 10-8). The evidence provided by the witnesses should be a formidable obstacle to any sincere skeptic.

Evidence Score = 8 (increasing the probability of an authentic Book of Mormon by about eight orders of magnitude).

The Narrative

You spend a long, cold night burrowed in a coarse wool blanket, a blanket you shake off wearily as shards of daylight pierce through cracks in your tarred cabin roof. As you dress and prepare to tend the animals on your small farm, your eyes catch the book you’d lain on your table the night before. You consider leaving it where it is, or filing it away on your shelf, never to be bothered with again. But the same thought that kept you awake most of the night keeps scratching at the back of your mind. The young man you spoke to the night before was wrong—he had to be. Chore after chore falls sway to your practiced hands, but that idea wriggles a worn, looping path through your thoughts. As you feed the chickens, you notice that your hands keep sifting the same handful of feed. But if his errors are so certain, why can’t I ignore them?

You drop the bag of feed, letting it spill into the pen. You’re soon back in the cabin, moving the stool back to the table from where you’d left it the night before. You open the book, more forcefully than you’d meant to, reading the words almost out of spite.

“The Book of Mormon: An account written by the hand of Mormon upon plates taken from the plates of Nephi." So far, so much nonsense, you find yourself thinking. You skim the rest of the title page, as well as the clerk’s note opposite to it. You turn the page and find a preface—it contains similar silliness about devils and plates. You turn the page again, but your hand slips, and instead of a single page turning, you accidentally turn the whole book. You find yourself facing the last few pages, and something about them grabs your attention:

“The Testimony of Three Witnesses”, it reads, and contains a statement from three men who claimed to have seen those plates, that they were shown them by an angel, and that a voice from God declared that the record was true. The back side of the page shows a similar testimony, from eight others (with a curiously limited number of last names), who claimed to have seen and handled the plates.

You wonder at the nature of men who would stake name and reputation on this book—you would certainly be embarrassed to admit to seeing an angel, even if it were true. Such a thing would seem improper for polite company. Of course, it should hardly be surprising that religious fanatics would say anything to gain power and prestige. You imagine meeting these people—surely blowhards the lot of them, unreliable, their testimonies wavering at the first sign of difficulty or internal strife.

But no, you think, I should be a bit more fair to these ignorant people. Perhaps they were of reliable and honest stock, but were instead deceived, hypnotized into believing in false visions. You aren’t an expert in such things, but the stories you’ve heard must have some truth to them. Then again, such tales of mesmerism en masse seemed every bit as fanciful as angels and gold plates. You turn the page, almost unwillingly, and a somewhat disturbing thought remains. It seems unlikely that anyone could give such bold and straightforward testimony to an apparent fraud, particularly if those witnesses proved true to their testimony.

The Introduction

Of all the types of evidence surrounding the Book of Mormon, few are as persuasive—or as derided—as the witnesses—those providing eye-witness testimony to the reality and truth of the book. Rightly or no, people place a lot of weight on the word of people who were there to see for themselves. Yes, there are cases and contexts where eyewitness testimony shouldn’t be trusted. But regardless of whether they’re trustworthy, the detailed, consistent, matter-of-fact accounts of the three and the eight have to be dealt with; they can’t just be left alone. Critics of all stripes have spent buckets of ink doing just that–failing to leave them alone. They tend to do so through two means: 1) positing a large-scale conspiracy on behalf of those who saw or otherwise experienced the plates, or 2) suggesting that Joseph fooled those witnesses by some combination of artifice, showmanship, and psychological trickery. How likely are either of those explanations? There isn’t much solid data to go on here, particularly when it comes to the likelihood of maintaining a conspiracy, but some informed guesswork should allow us to form an initial answer to that question.

The Analysis

The Evidence

This is likely to be the most contentious part of this episode—to hear believers and critics discuss the witnesses is akin to hearing Democrats and Republicans talk about Trump. They’re using the same words, but you’re pretty sure they’re not talking about the same people. To one side we have witnesses who are honest, reliable, and unflaggingly consistent. To the other we have untrustworthy, magic-thinking double-talkers. There’s very little room for consensus.

So here it helps to rely on the best primary sources available: first-hand accounts from the witnesses themselves and sober interviews from the hundreds who visited them later in life. When we do that, we find a rather impressive body of evidence in favor of the Book of Mormon. People like Richard L. Anderson aren’t wrong—the three witnesses powerfully defended the Book of Mormon at dozens of opportunities spanning the rest of their lives, and this despite all three leaving the church and having strong personal disagreements with Joseph Smith. The eight left fewer written testimonies, but were no less consistent in their witness, even though some (i.e., John Whitmer), had every reason and every opportunity to tear down Joseph’s story.

How about those interviews or accounts where the witnesses contradicted their testimony? Here’s the thing—the existence of unflattering hearsay accounts is perfectly consistent with an authentic Book of Mormon. We would expect critical voices, threatened by the potency of the church, to invent stories about the witnesses in an attempt to discredit the movement. To be fair, we’d also expect those stories to be unreliable, uncorroborated, and contradicted by the witnesses themselves, all of which characterizes those accounts. We’d also, as I’ve documented in a previous episode, expect even reliable accounts to differ in minor details when told over the course of decades. Those stories simply don’t tell us anything about the veracity of the witnesses one way or another.

Unfortunately, the same goes for other potential witnesses of the Book of Mormon. We don’t have to explain Mary Whitmer’s account of seeing the Angel Moroni or Emma handling the plates (as compelling as they are), because we’d expect those sorts of uncorroborated stories to be floating around even if the Book of Mormon was a fraud. That leaves us with the three and the eight—the two direct, corroborated, concrete experiences with the plates of which we have record.

So let’s go ahead and try to account for that evidence.

The Hypotheses

There are a lot of different ways the witnesses could’ve played out. For the sake of parsimony, rather than multiply various combinations of hypotheses, we’re going to focus on three: the hypothesis of authenticity, and the two main critical hypotheses we’ve already mentioned (i.e., conspiracy and deception).

The witnesses were reporting real experiences with an angel and with the plates—For this theory, both Moroni and the plates were real and fully authentic. The three witnesses saw both the plates and the angel, and the eight saw and handled the plates, exactly as they report in their testimonies. These plates wouldn’t have been pure gold (as they would’ve been too heavy), but is much more likely to have been a copper/gold alloy (which happens to have been conveniently used in ancient Mesoamerica).

The witnesses conspired with Joseph to concoct entirely fictional witness accounts—This theory posits that the events referred to in the witness accounts never took place at all—that Joseph never took any of the witnesses into the woods, and they never saw or even thought they saw, either plates or angels. Under this scenario, the witnesses would’ve simply been lying through their teeth repeatedly for decades.

The witnesses believed they saw angels and plates, but were really victims of fraud by Joseph—In this case, Joseph would have had to have found some way to convincingly fool these eleven witnesses. Again, to keep it simple, we’re going to assume that Joseph was able to do two things to pull off his ambitious fraud: 1) make a set of fake plates to fool the eight, and 2) hypnotize the three witnesses into believing that they saw an angel.

There is another possibility that I think is worth discussing here. Isn’t it possible that the witnesses were merely mistaken about what they saw? That their testimonies are genuine but also genuinely untrustworthy, as is the case for a lot of eyewitness testimony? In short, no. It’s true that we shouldn’t put blind trust in eyewitnesses, but that doesn’t mean we get to ignore anything eyewitnesses say. There are specific factors that can make eyewitness testimony unreliable, stuff like ambiguous stimuli, physical distance, high levels of emotion and anxiety, time pressure, and leading questions. None of that applies to a bunch of guys walking into the forest in broad daylight and leisurely handling a solid material object. It also doesn’t apply to being spoken to directly by a divine messenger clothed in holy light. Either they were lying or there was some sort of convincing and stupendous deception, but there isn’t any room for them to be simply mistaken.

Prior Probabilities

PH—Prior Probability of Authentic Witnesses—Here we begin where we left off last time, where the posterior probability given the evidence considered so far was p = 1.2 x 10-37. You can see the evidence we’ve considered thus far below:

PA1—Prior Probability of Conspiring Witnesses—This one’s somewhat tricky. Hoaxes and conspiracies are fairly common phenomena, but we have little sense of how likely they are in comparison with hypnotic suggestion as an explanation for strange occurrences. Given that it would generally be easier for people to just lie rather than having to genuinely deceive people, we’re going to let the conspiracy hypothesis take a substantial portion of the remaining probability, with an estimate of p = .90.

PA2—Prior Probability of Deceived Witnesses –Subtracting the probability of the other hypotheses leaves an estimate of p = 0.1 – 1.2 x 10-37 for how likely it would be for the witnesses to be deceived.

Consequent Probabilities

CH—Consequent Probability of Authentic Witnesses—As mentioned earlier, my own opinion is that the evidence we have fits the hypothesis of authenticity about as well as we could expect it to. The record is strongly affirming, but not spotless, which fits a world where both the witnesses and a myriad of critical voices are human beings capable of error. I have no problem assigning a consequent probability of p = 1 for the evidence we have available.

CA1—Consequent Probability of Conspiring Witnesses—Conspiracy is always a tempting option when it comes to explaining away inconvenient phenomena. It is also, tellingly, the go-to explanation whenever the evidence is otherwise strong—moon landings and spherical earths come immediately to mind. Footage of men walking on the moon? Conspiracy. GPS? Conspiracy. Incriminating photos and video of an incredibly spherical earth-like object? Obviously the product of a worldwide plot to keep the sheeple in line. Presenting evidence against conspiracy does nothing but prove that you, too, are part of a never-ending series of co-conspirators. A conspiracy theory can never be proven wrong, and often relies on the strength and coherence of the evidence itself as a core part of its argument.

But real-life conspiracies are notoriously difficult to maintain, and the difficulty in doing so increases exponentially with the number of people involved. There’s always a chance that someone in the conspiracy will turn on their fellow conspirators. Silence is never guaranteed, and it certainly wouldn’t have been guaranteed for Joseph and the fledgling restoration.

Our task, then, is to figure out how likely each of the witnesses would’ve been to keep the secret quiet, and if you were hoping to rely on data, you’ll be sorely disappointed. Laboratory studies on ratting out co-conspirators are thoroughly interesting in their own right, but they’re unlikely to be applicable to the nineteenth-century frontier. As I mentioned in the introduction, we’re left instead with a lot of guesswork, but hopefully it’s guesswork that’ll be as fair as possible to the critical perspective.

There are a lot of factors we could take into account when judging the reliability of the witnesses’ testimony. We could talk about their well-known reliability in the business arena or their impeccable reputation for honesty among their non-LDS peers. But no one’s going to agree on the strength of that evidence or the weight that should be applied to it. Instead, I propose to include three types of relatively uncontroversial evidence that have unmistakable bearing on the likelihood of keeping Joseph’s alleged secret.

One of those is the relation of the witnesses to the prophet himself. We (and several critics) would be right to expect Joseph’s immediately family to be likely to stay true to him and his story, even if it was false. But that means the converse of that is also true: non-relatives would have substantially less reason to stick up for Joseph, especially under duress. That means that the testimonies of Oliver, Martin, and the six members of the Whitmer clan (including Hiram Page, who was married to a Whitmer), need to be accounted for in some way. Perhaps, though, we don’t need to account for it very much. We’ll assume that, independent of other factors, non-relatives would be 90% as likely to keep the secret compared to Joseph’s flesh and blood.

The second factor is the immediate threat of death. The witnesses experienced all manner of persecution and ill-treatment at the hands of friend and foe. One could make the argument that this persecution could’ve been a badge of honor for the conspirators—part of the price to be paid to keep the conspiracy intact. That’s a harder argument to make, though, when it comes to the witnesses being literally under the gun. During the persecutions of Missouri, both David Whitmer and Christian Whitmer each faced down an armed mob that threatened to pull the trigger if they didn’t deny the Book of Mormon. Hiram Page was beaten within an inch of his life because he wouldn’t deny his testimony. None of them did, and all said they would rather die than deny what God had shown them. Hyrum Smith, obviously, faced down his own set of muskets, and also chose (and received) death rather than betrayal.

Now, these death threats aren’t proof—there have been plenty of martyrs that have laid down their lives for false causes—but it does make conspiracy less likely. Many have given up secrets at the threat of violence and death, and there was the chance that the three and the eight would’ve as well. How much of a chance? I’ll give what I feel to be a conservative estimate, with a 50% chance of a conspirator turning tail with a gun at their chest.

Last, we’ll consider the factor that I personally think is the hardest to deal with—the witnesses’ severe habit of personal apostasy against Joseph and the church. Fully six of the eleven witnesses would leave the church, either through excommunication or of their own accord. Each of those six demonstrated personal animus against Joseph and had every reason to blow the church wide open. All of them had opportunities to do so—some practically begged them to. But all took great pains to uphold their testimony, with little to no motivation and at great personal and professional risk.

What should we do with this apostasy? How likely would someone be to maintain the story even after parting ways with the church? As a psychologist, this is the issue that gets to me. It’s extremely difficult for me to imagine someone of sound mind acting so contrary to their own emotions and motivations. In my view, it’s essentially impossible. But I’m going to be as generous as I know how to be. We’ll assume that the apostates would still have a 10% chance of maintaining their testimony, even when out of the church.

The result can be found in the table below. I’ve assigned the factors indicated above to each of the witnesses, giving each a value of 1 when the factor wasn’t present. The result is an estimate of the probability of each witness maintaining their testimony if they had just made up their stories whole cloth. The probability of all eleven maintaining their testimony can be found by multiplying all of their estimates together, leaving us with a rather small consequent probability of a conspiracy, at p = 2.69 x 10-8.

Now, an important assumption to make explicit here is that the probability of each witness failing to recant their testimony is independent—that each one has their own chance of doing so independent of what any of the others are doing. It’s possible that this assumption may not hold–it’s true that once one went against their testimony it would be much easier for others to do it. But I would argue that prior to that each would have an independent chance of being the first to go against the grain, and that’s the probability that I’m trying to tap into with these estimates.

CA2—Consequent Probability of Deceived Witnesses—So the probability of conspiracy seems rather remote. How about the probability of deception? Is it probable that Joseph could have fooled people into thinking they saw authentic plates and angelic visitors?

Let’s start with the plates. Those unfamiliar with metalworking might assume that it would be easy to put together a fake set of plates. After all, we see fake sets of plates all the time in church media. But all those fake plates had the benefits of modern manufacturing techniques. Joseph might’ve been able to get his hands on a set of tin or copper plates, but the witnesses would’ve all been very familiar with either one, and I haven’t seen a method proposed that would’ve given tin or copper a convincingly gold appearance (and I can’t imagine a shoddy frontier paint-job doing the trick). Joseph’s best bet in that case would’ve been smelting and hammering out a mixture of gold and copper.

Setting aside the problem of Joseph having the money to purchase the raw materials, hammering out sheets of metal in the early nineteenth century was no trivial matter. You can get a sense of what it took from this blog post, where an experienced modern metalsmith takes 8-10 hours just to manually hammer out a sheet of metal about a third the estimated size of a Book of Mormon plate.

The number of plates themselves is an interesting question, and one that’s important for our estimate. If we go by how many plates it would’ve taken to contain the text of the Book of Mormon, that gives us an estimate of 20 plates, at the low end. That estimate wouldn’t include the “sealed” portion of the plates, comprising about a third to a half of the plates, which weren’t part of the Book of Mormon proper and weren’t specifically examined by the witnesses. If we instead go by this set of tin plates that (very) roughly approximate size and weight of that reported by the witnesses, there might have been around 80 total plates (I had to count the plates like you might count rings on a tree, so that might be off a bit). Yet other estimates, based on a rather thorough metallurgic analysis, suggest there could’ve been between 300 and 1,000 plates. We’ll low-ball this estimate on behalf of the critics, assuming 20 unsealed plates, plus the sealed portion. That would mean Joseph would have to have spent at least 480 lonely, sweaty hours in a secret blacksmith shop hammering out his plates.

And then he actually had to do stuff with those plates. The plates weren’t empty. The witnesses are clear on this point—the unsealed portion was filled on both sides with small, intricate engravings. Even if you assume these engraved markings were gibberish (which they probably weren’t), he still would’ve had to manually engrave a large number of characters into the metal. If we assume that the density of characters matches what we see in the well-known Caractors document, which contains transcriptions of characters that were purportedly on the plates, I would guess that there were about 450 on each side of a plate (the approximately 222 characters on the document take up a little less than half a page). That would mean, with around 20 unsealed plates, that Joseph would’ve had to engrave about 18,000 characters. That would probably take at least as much time as it would’ve taken to hammer out the plates themselves. It’s hard to know for sure, but to make a conservative estimate, let’s consider this article on a 1990 professional metal engraver, who charged $1.50 a letter for engraving. Even if Joseph went at a $60/hour pace (40 characters/hour) chipping away at the plates (which would make him an exceptionally well-paid engraver), that still means we could’ve expected Joseph to take at least 450 hours to engrave the Book of Mormon. All told, we’re looking at an estimated 930 hours of work to make a convincing set of plates that match the witnesses’ account.

As we’ve discussed before, with time comes risk—the longer he takes to make the plates, the harder it is not to get caught. Even if there was only a 1% chance of him getting caught in each hour of work, that means the probability of him getting away with that, even assuming he could get the raw materials together, would be p = .99930 or .0000872.

Now we come to the three witnesses. A fake set of plates would still be necessary to fool them, but that alone wouldn’t have been enough. No dude in a robe could manage to fool anybody into thinking they were seeing an angelic being. Some have posited hypnosis as a probable cause of their delusions—after all, it’s well known that it’s possible to use hypnosis to plant false memories, and to be convinced of their veracity to the point of accusing loved ones of horrific acts and sending them to jail. Surely the superstitious folk of the early nineteenth century could be fooled in similar fashion.

Except the average citizen of the 1830’s frontier would’ve heard of mesmerism and would’ve been fully aware of what it could do. Each of the three flatly denied the possibility of hypnosis. What’s more, hypnotism has never been a sure thing, and there would’ve been no guarantee that hypnosis would work, even for the best of hypnotists. Only about 10% of individuals fit the criteria of "highly susceptible" to hypnosis, which would’ve likely been required for them to accept a suggestion as outlandish as this, and to hold to it so strongly. Among those highly suggestible individuals, difficult suggestions are only accepted about 75% of the time. That means that each of the three witnesses would’ve only had a p = .075 chance to accepting a hypnotic suggestion of the kind we’re talking about here. The odds of all three even accepting that suggestion would be quite low, at p = 0.0753 or .00042188.

And once you have the suggestion, you have to make it last. Hypnotic suggestions tend to decay rather quickly, often within weeks. Remember, Joseph wouldn’t have just had to have them accept a false memory, but also would’ve had to have instructed them to forget being hypnotized. To have that suggestion last for decades would’ve been prodigious, to say the least. How likely would it be for him to pull that off? Assuming the average suggestion lasted as long as a year (which wouldn’t have been the case), with a standard deviation of an exceedingly generous five years, the odds of the suggestion lasting 20 years, 58 years, and 45 years respectively for Oliver, David, and Martin would be astronomically low, and the odds would be even worse if we used a more appropriate statistical distribution for this sort of phenomenon (e.g., poisson or negative binomial).

But statistical impossibilities hardly seem sporting. We’ll assume that if the suggestion stuck that it would stick forever. Even so, the consequent probability of Joseph both successfully hypnotizing the three witnesses and making a set of believable plates without getting caught can be calculated by multiplying .0042188 by .0000872, which comes out to p = 3.68 x 10-8.

Posterior Probability

PH = Prior Probability of the Hypothesis (our guess at how likely it would be for Moroni to have a chat with the witnesses, based on previous evidence, which is p = 1.2 x 10-37).

CH = Consequent Probability of the Hypothesis (our estimate of how likely we would be to have our current set of recorded testimonies from the witnesses, if the Book of Mormon were authentic, which I set at p = 1).

PA1 = Prior Probability of the Alternate Hypothesis (our assumption that conspiracy is much more likely than the existence of angelic beings, p = .90).

CA1 = Consequent Probability of the Alternate Hypothesis (the probability of a conspiracy of 11 people, most of which unrelated to Joseph, maintaining the conspiracy despite both apostasy and the threat of death, which I estimate at p = 2.69 x 10-8).

PA2 = Prior Probability of the Alternate Hypothesis (our assumption that deceiving the witnesses is more likely than angelic visitation, but not as likely as conspiracy, or p = 0.1 – 1.2 x 10-37).

CA2 = Consequent Probability of the Alternate Hypothesis (the likelihood of manufacturing a convincing set of plates without getting caught, while also getting three people to accept an outlandish hypnotic suggestion, or p = 3.68 x 10-8).

PostProb = Posterior Probability (our new estimate for the probability of an authentic Book of Mormon).

| PH = 1.2 x 10-37 | |

| PostProb = | PH * CH |

| (PH * CH) + (PA1 * CA1) + (PA2 * CA2) | |

| PostProb = | (1.2 x 10-37 * 1) |

| ((1.2 x 10-37) * 1) + (.9 * 2.69 x 10-8) + ((0.1 – 1.2 x 10-37) * 3.68 x 10-8) | |

| PostProb = | 3.78 x 10-30 |

Lmag = Likelihood Magnitude (an estimate of the number of orders of magnitude that the probability will shift, due to the evidence)

Lmag = log10(CH/((PA1* CA1) + (PA2* CA2))

Lmag = log10(1 / ((.9 * 2.69 x 10-8) + ((0.1 – 1.2 x 10-37) * 3.68 x 10-8)))

Lmag = log10(1 / (2.42 x 10-8 + 3.68 x 10-8))

Lmag = log10(1 / 2.79 x 10-8)

Lmag = log10(35,849,747)

Lmag = 8

Conclusion

Well, that certainly is interesting. We haven’t even really cracked open the book yet and the available evidence has already increased the probability of an authentic Book of Mormon by over 10 orders of magnitude overall. But, worry not, there’s definitely room for the text of the Book of Mormon itself to undo this progress. For now, though, it’s clear that the narrative surrounding the coming forth of the book is thoroughly unexpected under the assumption of fraud. A conspiracy involving the eight and the three would’ve been extremely hard to maintain, and creating a fake set of plates would take a ton of time and thereby expose Joseph to substantial risk of being discovered. The witnesses themselves are extremely compelling in that regard, moving the needle toward authenticity by around eight orders of magnitude. Not bad for eleven magical thinkers on the nineteenth-century American frontier.

Skeptic’s Corner

As with my previous episode on the dictation process, the estimates for the likelihood of creating a set of plates rely on an independent risk of discovery per hour of work, and the same limitations that I discuss there apply here. In my mind, though, it’s even less plausible for Joseph to get away with this sort of intensive effort, which would require specific blacksmithing facilities and inscription tools, than it would for the act of writing the book. It’s possible someone might discover a plausible way for Joseph to tint a set of tin or copper plates gold, which would cut down his risk considerably. But in my mind, there’s no getting around the time it would take to engrave even as few as 20 plates (and 450 hours is a pretty generous estimate as it is), and anyone playing the a fortiori game on the critical side would be obliged to have Joseph making something on the order of 300 plates.

It’s important to acknowledge that this analysis involved a ton of guesswork regarding the witnesses and the plates. The final evidence score essentially represents a combination of a bunch of different guesses, which makes it no better than a guess. The witnesses didn’t photograph the plates, we don’t know what they looked like, or how many they were, or how densely they were inscribed. That’s a lot of holes to try and fill. But those kind of guesses, based on clear, conservative assumptions, are a necessary starting point. Making a better guess will require more thorough reasoning and/or hard data, and we’re not ever likely to get the latter.

It may also be possible that some other psychological mechanism is in play besides hypnotism when it comes to the experience of the three witnesses. But the potential alternatives, such as priming, shared delusion or hallucinogenic substances, aren’t likely to fare any better from a statistical standpoint (all priming can do is make someone somewhat more likely to interpret ambiguous stimuli in a hallucinatory way, and can only do so reliably under conditions of psychosis; shared delusions don’t generally involve hallucinations; and the experiences of the witnesses don’t align well with any known hallucinogen). The best bet from my perspective would be to play around with hybrid theories that mix conspiracy and deception—say, a conspiracy that involves only his family members, who then help him create the plates. I’m sure the critics will continue to display their unbounded creativity, as they always have. But it’s clear to me that the witnesses deserve to stand as strong evidence in the Book of Mormon’s favor.

Next Time, in Episode 6:

When next we meet, we’ll switch from religion to everyone’s other favorite family dinner topic: politics, and the odds that your politics would agree with God’s on every particular.

Questions, ideas, and glares of disapproval may be cast down on BayesianBoM@gmail.com or submitted as comments below.

Kyler,

Thank you for the excellent series of essays. You marshal expertise in data science and extensive knowledge of the Book of Mormon and church history. Your writing is engaging and entertaining. One of the key contributions of your esssays is a semi-quantitative ranking of evidences for the Book of Mormon.

The truthfulness of the Book of Mormon is a central question to members and friends of the Church. As Elder Jeffrey R. Holland wrote, “everything of saving significance in the Church stands or falls on the truthfulness of the Book of Mormon and, by implication, the Prophet Joseph Smith’s account of how it came forth . . . it is a ‘sudden death’ proposition. Either the Book of Mormon is what the Prophet Joseph said it is, or this church and its founder are false, a deception from the first instance onward.”

As expected, the witnesses for the Book of Mormon constitute one of the strongest evidences. Elder Holland: “Each of the three and several of the eight had dificulty with the institutional Church during their lieftimes, including years of severe disaffection from Joseph Smith personally. Nevertheless, none of them – even in hours of emotional extremity or days of public pressure – ever disavowed his testimony of the divinity of the the Book of Mormon.”

I’m looking forward to more essays. I’m curious as to whether you will consider the personal witness of the Holy Ghost in the Bayesian framework! The Book of Mormon teaches that the power of the Holy Ghost can provide an individualized token of truth to sincere readers.

Thanks Josh!

Though I firmly believe in the power of a personal witness through the Holy Ghost, it’s not something I’m going to be tackling from a Bayesian perspective. First, that sort of personal evidence is just that: personal. It’s not a transferable experience that we can pull out and look at together with critics, coming to an agreement on what it is, what it means, and how it should be weighed.

Second, many of those reading this have lost their trust in impressions received through the Spirit. Not everyone has been able to feel them (though how you could go through a lifetime in the church or through two years of mission experiences without doing so is beyond me), and those that have felt them in the past have reinterpreted them as an internal psychological phenomenon, subject to confirmation bias. Now, I haven’t experienced them in that way (these experiences aren’t something I’ve been able to generate internally, and my impressions often run counter to my own predilictions and preferences), and I’ve come to trust them as an extremely valuable guide that has led me to witness a variety of miracles, kept me out of serious trouble, and pushed me toward everything in life that I currently value. But for those that have lost that trust, spiritual impressions just aren’t going to be persuasive evidence. As with other kinds of trust, it would have to be built back from the ground up, and that would probably require first seeing the church and its truth claims as a live option.

I do touch on the subject a bit in my concluding episode, but otherwise I stick to the type of evidence everyone has ready access to.

The planet Roshar is a fascinating place. Roshar is full of magical objects called shardblades. Shardblades look like really long swords, weigh much less than you’d guess for their size, and can cut through solid stone with ease. But if you cut through a living thing with the shardblade, the blade passes through the living tissue without actually severing it. The living thing turns black and dies, but isn’t cut. Totally bizarre.

Despite practically being ubiquitous on Roshar, shardblades don’t exist in the real world. We not only have no actual direct evidence of their existence, we have positive reasons to believe that if they did exist we’d know about them—not knowing about them is evidence that they don’t exist and never did.

Say 11 witnesses came forward and said they saw an actual shardblade with their own eyes. They claim their good friend Brandon Sanderson showed it to them and according to their judgement about such things, it was an authentic shardblade.

Would that constitute strong evidence that shardblades are real? Would it constitute evidence that the Stormlight Archive is actual history, translated from the original Alethi through the power of a spren? No. But what if the witnesses were really honorable men recognized as having good judgment? That would have no bearing on the matter. It might make me curious enough to want to see the shardblade and get an opinion on it from a physicist. But say I was then told that I couldn’t do that because after showing the shardblade to Sanderson’s eleven witnesses, the Stormfather took it away to Shadesmar. If I heard that I’d be beyond suspicious of the whole thing and would feel more than comfortable dismissing it on its face without needing to offer an alternate theory about what the witnesses saw.

Like shardblades in Roshar, the world of the Book of Mormon is full of records on metal plates. The brass plates. The small golden plates. The large golden plates. The 24 plates from Ether. The golden plates that Mormon and Moroni wrote their summary on. It turns out that in the world of the Book of Mormon, the production of gold plates was so common the material, composition, dimensions, and hole placement had all been standardized for 1,000 years—that is the only explanation for how Mormon could have inserted the small plates of Nephi into his own plates in a way that caused the difference between the two sets of plates to be unnoticeable to the witnesses of them.

Writing on metal plates is ubiquitous in the Book of Mormon. But bound books on metal plates are so unknown, impractical, and unrealistic in the real world that the Book of Mormon’s claim on the matter must be considered an anachronism that in and of itself disproves the Book of Mormon. On the other hand, the witness statements, such as they are, can be considered enough to counteract the weight of the anachronism. On the whole I don’t see the witness statements as evidence in favor or against the historicity of the Book of Mormon.

My probability remains at 1-in-4,000,000.

Thanks for your comments Billy.

“My probability remains at 1-in-4,000,000.”

You did it!

This is, of course, quite easy to do if you ignore all of the issues discussed in the essay, which you’ve done quite handily here. I kind of miss how our banter worked in the first essay, where you actually engaged with the arguments and the evidence. Hasn’t quite worked that way since then.

“Roshar is full of magical objects called shardblades.”

Dang. I can’t object to this analogy. I love me a good shardblade.

“Would that constitute strong evidence that shardblades are real?”

If our minds really were open to any possibility, in the true Bayesian fashion, then the answer here would have to be: it depends. For me, it’s not the raw fact of 11 witnesses that’s necessarily unexpected, it’s their behavior after providing that testimony. If those witnesses had all gone through what the BofM witnesses went through and still maintained their witness of the shardblade, I would definitely have some questions. I would explore the possibility that they did actually believed they saw a shardblade, and whether Brandon had the ability to produce something that looked enough like a shardblade to pass the witnesses’ muster. If he didn’t, in the same way that Joseph didn’t with the plates, then I’d have to admit I had a real mystery on my hands–one to which I had no ready explanation. It would still be possible that either conspiracy or deception were ultimately what produced the congregate testimony of the shardblade, but pending some other, better theory, I’d be forced to count it as evidence in the shardblade’s favor.

To do otherwise would be to trust in some as-of-yet undiscovered explanation for what could produce the evidence at hand, which sounds an awful lot like an exercise of faith (and of the shelf we’ve discussed previously).

Given the supernatural physical properties of the shardblade, though, my prior for it would probably be even smaller than for an authentic BofM, which means that this testimony alone wouldn’t ultimately convince me of its authenticity. When it comes to the BofM, the witnesses make the biggest splash so far, but they also aren’t alone–they’re ultimately backed up (or perhaps hindered) by the text itself. If, alongside the witnesses, we had a whole bunch of people with greyed out, useless limbs, and giant slabs of stone with magical sword-like cuts through them, the witnesses themselves would start to look pretty credible.

“But bound books on metal plates are so unknown, impractical, and unrealistic in the real world that the Book of Mormon’s claim on the matter must be considered an anachronism that in and of itself disproves the Book of Mormon.”

I’ll let readers decide for themselves how true this statement is, in light of the historical record:

https://knowhy.bookofmormoncentral.org/knowhy/is-the-book-of-mormon-like-other-ancient-metal-documents

Hi Kyler,

In my analysis, the hypothesis I’m considering is quite specific: the Book of Mormon an accurate translation of an authentic ancient document. The testimonies of the eleven witnesses simply doesn’t have any bearing on that.

Part of the problem with this is how we are supposed to handle stories of the miraculous. As an example of the problem, several years ago a really sweet lady told me she figured out the issue of the dinosaur bones: Satan put them there to confuse us.

How does one go about proving that she wasn’t right about that? When one believes that supernatural forces can tamper with the evidence, what does a rational evaluation of the evidence even mean?

The testimony of the witnesses is a similar thing–the only reason their testimony matters is because God miraculously made the plates disappear. When God is going to such extreme measures to remove the actual physical evidence that would corroborate the witness testimonies, how seriously does God expect us to take their statements? And for that matter, even if the witnesses really did see something, what is the probability that it was really an angel and not Satan himself transformed into an angel of light (2 Corinthians 11:14)?

Regarding metal plates, that link from Book of Mormon central was quite interesting and proves my point. The way it should have been applied was in Episode 1. In that episode, you should have compared how well the Book of Mormon fits in with 19th Century literature written on paper to how well it fits into ancient manuscripts that were written on metal. According to your link:

“When it comes to length, the Book of Mormon is rather unique. Its ancient engravings were translated into over 500 pages of English text. In contrast, the amount of text found on most other known metal documents is quite short, often requiring a few pages or less when translated into English.”

“How does one go about proving that she wasn’t right about that?”

If we were serious about examining that hypothesis, we could instead consider other evidence. Certainly seems unlikely to me that Satan would work so hard to put together a book that emphasized Christ so thoroughly, or a movement that did so much good in the world and for its adherents.

“how seriously does God expect us to take their statements?”

Given that he specifically foretold and made sure that these witness testimonies came about, I’d assume very seriously.

As for why God would provide witnesses but not leave behind the relic itself, a few reasons present themselves, including preserving the role of faith (as verifiable plates would give the game away), maintaining control over the text (as plates could eventually lead to rival translations), and emphasizing the actual content of the book (which would certainly be lost in the ensuing controversy as everyone rushed to examine the plates instead of the text).

“that link from Book of Mormon central was quite interesting and proves my point.”

Only if you ignore the paragraphs immediately following your quote, which provide a number of examples where the text would’ve been quite long indeed.

If you want to argue that it would be unlikely for the text to be as long as it is if published on metal plates, feel free to collect the data and fit the distribution. Given that the more appropriate comparison would probably be scriptural histories recorded on metal plates (rather than all metal documents), my guess is that the Book of Mormon’s thumb doesn’t stick out as far as you think it might.

There is a little mistake in the table: The probability of Hiran Page should be the same of David Whitmer. The total calculation reported 2.69*10^-8 is correct, but if we multiplicate the probability of all witnesses in the table the number is going to be the double, because Hiran page should be 0.045; not 0.09

Thanks Marcelo. I’d noticed this myself when taking a look at it after it was published. Should be an easy fix.