Intro/FAQ ⎜ Episode 1 ⎜ Episode 2 ⎜ Episode 3 ⎜ Episode 4 ⎜ Episode 5 ⎜ Episode 6 ⎜ Episode 7 ⎜ Episode 8 ⎜ Episode 9 ⎜ Episode 10 ⎜ Episode 11 ⎜ Episode 12 ⎜ Episode 13 ⎜ Episode 14 ⎜ Episode 15 ⎜ Episode 16 ⎜ Episode 17 ⎜ Episode 18 ⎜ Episode 19 ⎜ Episode 20 ⎜ Episode 21 ⎜ Episode 22 ⎜ Episode 23

[Editor’s Note: This is the eighth in a series of 23 essays summarizing and evaluating Book of Mormon-related evidence from a Bayesian statistical perspective. See the FAQ at the end of the introductory episode for details on methodology.]

The TLDR

It seems unlikely that Nephi could have built and sailed a boat from the Arabian Peninsula to the New World.

Though some critics have labeled Nephi’s voyage as an impossibility, those perceptions are largely based on the assumption that Nephi had to have built a Renaissance-style sailing vessel, as if the Nina, Pinta, or the Santa Maria were Nephi’s only options. That assumption doesn’t hold, given a variety of demonstrated oceanic voyages that rely only on ancient technology. Given the success rate of those voyages, and a conservative estimate of 16,000 man-hours of available labor for Nephi and his family, I put the probability of him being to build a boat at p = .3085 and the probability of him being able to sail it the requisite 17,000 miles at p = .0265. The odds would have been stacked against Nephi, but not enough to drastically alter the Book of Mormon’s authenticity.

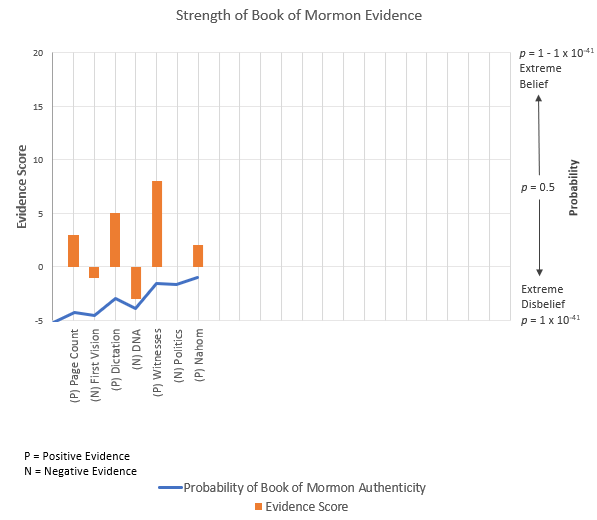

Evidence Score = -2 (reducing the probability of an authentic Book of Mormon by two orders of magnitude)

The Narrative

When we last left you, our ardent skeptic, you were following the desert adventures of a strange little family in a strange little book, one given to you by a stranger. You read on, curious where this tale will go next, with the narrative taking them from a desert burial to a further eight years wandering in the vast wilderness of what you presume is the Arabian peninsula. After that, though, it seems as though they find some peace, arriving at a lush coastal area they term Bountiful. But there can be no lasting peace for these tragic figures, and it’s there that the story turns once again from the amusing (and at times confusing) to the ridiculous.

The young lad you had conversed with the night before had told you that this book told the story of the ancestors of the native peoples of the American continent, and so far you’d wondered how on earth the story was going to get these characters from Jerusalem to the other side of the world. You aren’t sure what you were expecting, but it certainly wasn’t having this decidedly non-nautical family build a boat, and then to have them sail that boat across the vast seas. You sympathize with the mutinous behavior of the two rebellious (and eminently sensible) brothers presented by the narrative—their foolish brother would have the ocean kill them as surely as any sword-stroke.

You scoot your stool back from the table and go back to your small library on the opposite side of the cabin. After a moment’s rummaging you pull out a small but elegantly detailed world map—one of your prized possessions. Your eyes quickly find the Arabian peninsula, and then follow two different trails through the sea toward the Americas—one through the Atlantic passing around the horn of Africa, and the other through the vast Indian and Pacific Oceans. You shake your head and give a chuckle. The book would have this Nephi outdo Columbus several-fold, beating him to the continent by over 2000 years. It would almost be easier to believe that angels had carried them over, or that they had bred flying horses to make the journey. You put the map down and return to the still-open book on the table, aghast at the audacity of this Joe Smith. It seems unlikely that anyone could build a boat capable of carrying an entire family on such a transoceanic voyage, and even less likely that they could survive the journey.

The Introduction

The transoceanic voyage of Nephi and his family has always been considered among the most incredible claims of the book. Critics rightly point out that boat-making is difficult business and that seafaring is extremely hazardous—they generally align with the mainstream academic consensus that there was no oceanic contact with the Americas prior to Leif Erickson and his Viking comrades. Faithful scholars, for their part, point to the serious, but minority, scholarship contending that there was indeed contact, and a great deal of it, ranging from the Polynesians to the Japanese to the Egyptians to the Phoenicians. Though the validity of that research is out of our particular scope, the general question is a workable one from a Bayesian perspective. Given access to materials, (divinely given) expertise, a navigational instrument, and the timeframe outlined in the text, how likely would it be for a small group of people to build a boat capable of carrying 30-40 individuals halfway across the globe, and then to have them survive the journey?

The Analysis

The Evidence

The story of Nephi’s sailing and boat-building activities, as recorded in 1 Nephi 17-18, provides a number of important pieces of information pertinent to our estimates. Nephi smelted woodworking tools from ore available within the Bountiful site and built a boat capable of carrying approximately 40 individuals using wood from timber

available in the vicinity (nowhere does he say that ore was used in the construction of the boat itself). We know that he had help from Laman and Lemuel (following a rather shocking altercation between them and Nephi), and would’ve had reliable assistance from at least Sam and Zoram, if not the sons of Ishmael, meaning there was as least five sets of hands working on the boat. We get very few other specifics about the boat itself, except that the revelation-provided instructions for building the boat resulted in a craft that didn’t look like any of the boats that Nephi was already familiar with (though it likely had a sail).

There’s no direct indication of how long it took to build the boat. John Sorenson estimates that they had at least two years based on the timing of the destruction of Jerusalem and Lehi’s being told of that destruction in a vision in the New World. However, there’s no rule saying that the vision had to happen immediately after that destruction, and contrary to Sorenson’s suggestion, the site of Bountiful may have been relatively isolated from contact with trade caravans (and with associated news of Jerusalem’s destruction). Aside from that conjecture, the next hard and fast date provided by Nephi is 30 years after leaving Jerusalem, by which time he’s in the promised land and has put down enough roots in the New World to construct a temple, meaning that Nephi technically could have had as much as 20 years to complete his journey. For argument’s sake, though, we’ll assume that he only had two years with which to build the boat.

The most plausible reading of the text has Nephi and his family sailing through the Indian and Pacific oceans to reach Central America (based on a western landing as suggested by the placement of the land of first inheritance), meaning that he would’ve traveled 17,000 miles to reach their final destination. We’re told, though, that he did have a workable navigation instrument available to guide them along the way. We’re not going to worry much about how long it took them to sail, since we’ll be calculating probabilities based on distance travelled, but it could have taken them a year or more to travel that distance by sea.

The Hypotheses

We have two relatively straightforward hypotheses to consider this time around:

Nephi’s voyage is authentic—The story in the Book of Mormon reflects a real Nephi who built a real boat, which took his real family from the real Arabian peninsula to a real American continent. Really.

Nephi’s voyage is fictional—The story in the Book of Mormon reflects Joseph Smith’s imagination. There should be no more reason to expect that the story would conform to reality than to expect eagles to be able to carry hobbits off of erupting volcanos.

Prior Probabilities

PH—Prior Probability of an Ancient Voyage—At the moment, given the evidence we’ve considered so far, the Book of Mormon is still rather incredulous. Our current estimate for the probability of an authentic Book of Mormon stands at p = 2.41 x 10-28. Here’s a look at where we’ve been so far.

PA—Prior Probability of a Fictional Voyage—That would leave the still-formidable remainder of our probability for the hypothesis of modern authorship, which would stand at p = 1 – 2.41 x 10-28.

Consequent Probabilities

CH—Consequent Probability of Ancient Authorship—To get an estimate for this probability, we’re going to need to try to calculate how likely it would be for Nephi to pull off this voyage. We’re going to treat it in two parts: 1) the likelihood of being able to build a boat given the time available to him, and 2) the likelihood of surviving a 17,000-mile ocean journey using an improvised oceangoing vessel.

Building a Boat. To some critics, we’ve already arrived at something they perceive as impossible. The ever-reliable Zelph on a Shelf frames the impossibility of Nephi constructing a boat thusly: 1) A transoceanic vessel would require iron, which Nephi wouldn’t have been able to smelt; 2) transoceanic vessels require a rounded hull, which would require building a dry-dock, which would have taken too long to build; 3) creating rounded hulls would’ve required steaming and bending the boards, which would’ve required at least Renaissance-level ship-making facilities and a large amount of labor; 4) storing food for the long journey would’ve required being able to pickle food, which Nephi wouldn’t have been able to do.

To me, this framework reflects both a lack of imagination and ignorance of non-Western means of ocean travel. Just because popular art depicts Nephi and his family riding a Renaissance-style ship to the New World doesn’t mean that they necessarily would’ve had to do so. European explorers were far from the only ones travelling the open seas. We don’t need to look any farther than the expeditions of Thor Heyerdahl to get a sense of what would be possible. Within a few months, Thor and his small team constructed a large oceangoing raft using little more than a few balsa logs, with neither a rounded hull nor any variety of metal in sight. It was able to carry his crew and necessary supplies over 4,300 miles across the Pacific just drifting on the wind and the current. Sorenson and others have suggested that Nephi could’ve used a larger version of that type of vessel to take his family to the promised land, and given what Thor and others were able to accomplish, it certainly seems plausible.

And, of course, regarding their point on food storage, it turns out that dates and dried meat have a pretty impressive shelf life, which is what Nephi would’ve had available, and that’s not accounting for the possibility of their diet being supplemented by a bit of ocean fishing. It may have even been easier than usual to gather those supplies given the unexpectedly verdant nature of the proposed Bountiful site. That site also would’ve had the requisite copper ore available for Nephi’s woodworking tools, which is much easier to smelt than iron.

So how long would it have taken to build an ocean-going vessel capable of carrying the entire Lehite clan? Even though Nephi wouldn’t have used European methods for constructing the ship, we can assume that it might take about the same amount of raw labor (or less) to put the thing together. The best estimates I could find were for Viking sailing vessels, which not only were able to travel oceanic distances, but were largely constructed by non-specialists, warriors, and farmers who added their spare labor to the project when they could. The best guess of anthropologists have suggested it took as long as 40,000 hours of labor to build a ship capable of carrying 80 people. But a Danish team, working in the early 2000s and making use of ancient methods, was able to build one much faster. They estimate that it would have taken actual Vikings around 28,000 hours of labor to construct.

Now that brings us to another interesting problem—the relationship between the carrying capacity of a boat and how long it takes to build. We can’t just divide the number of hours in half to estimate the labor required for a ship that could carry 40 people. Some of that labor would be required of a ship of any size, such as the work needed to craft the necessary tools and lay out a worksite. On the other hand, smaller boats might require a lot less in terms of build quality in order to keep them afloat. Data on how long it took to build ancient boats is pretty hard to come by. If we wanted to, we could collect a whole bunch of data on modern carrying capacity and boat lengths to try to build a better estimate. But relying on modern data might just lead us further astray.

Instead, let’s just assume that a substantial amount of the required labor, say maybe 5,000 hours of the total 28,000, consisted of that sort of preparatory effort, after which additional labor was used to add carrying capacity. If so, then we can divide the remaining 23,000 hours by two, and then add 5,000 to estimate the labor required for a vessel capable of carrying Lehi’s family. All told, we might expect such a vessel to take about 16,500 hours to complete.

Did Nephi have that much time available to him? If we go by the two-year time limit, and an assumption of five laborers, we can start to make some guesses. Assuming that Lehi and his party were able to live a hunter/gatherer lifestyle in Bountiful, they would have had a substantial amount of free time beyond what was needed to maintain subsistence living, and their wives and other companions could have done a lot to allow them to spend their time building a boat. Even those in more agrarian societies often didn’t need to spend the entirety of their time in subsistence labor. For the sake of creating an estimate, we’ll say that those five laborers could spend 8 hours a day working on the boat for an average of 200 days per year, that would mean Nephi and his makeshift crew could have devoted about 16,000 hours to the construction of the ship—just about enough to build a ship of the required size.

To get a probability estimate here, we’ll also need to estimate the variability in boat construction time. Given differences in the design of the ship and expertise of the work involved, that variability is probably pretty large. But let’s assume that ship construction would have a pretty tight standard deviation relative to its mean, say around 1000 hours (the smaller the deviation the better it would be for the critics). That would mean that Lehi’s ship is half a standard deviation away from our estimated mean, and that 30.85% of ships that size would require 16,000 hours or less of labor.

You’ll notice that there was plenty of red text above. It’s worth remembering, though, that exactness isn’t the goal—what we’re trying to do is build a reasonable, conservative estimate, and I’m pretty confident that this fits the bill. These numbers are a way for us to get a broad sense of how unexpected this kind of boat-building feat would actually be, and I don’t see the values above as being particularly far off. If they are, it’s probably in a direction that would help the critics. I feel quite comfortable using p = .3085 as our estimate for this part of the analysis.

The Risks of Ocean Travel. Once Nephi had a workable boat at his disposal, he and his family still had to face the perils of extended ocean travel. It would’ve been by no means easy for him or anybody else to make it across two oceans, though one would have to assume that the availability of divine intervention could’ve made things substantially easier. As is our habit, though, we’re not going to assume divine intervention. We’ll assume that Nephi would’ve faced similar risks as any other traveler on the maiden voyage of a first-time sailing vessel.

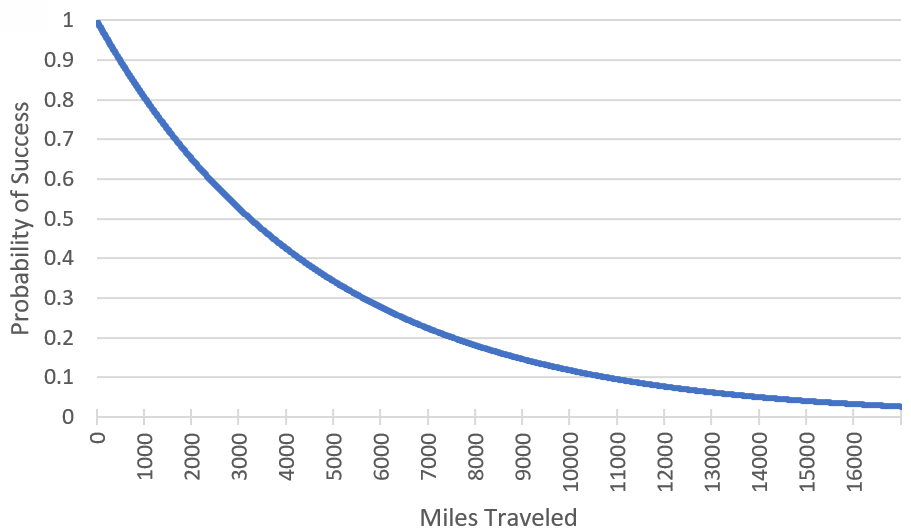

We can get a sense of that risk by looking at the various drift voyages, similar to Heyerdahl’s Kon Tiki, that have been attempted in the Pacific. Some of those voyages were successful, and others, including Heyerdahl’s own, didn’t go quite as planned—with boats becoming damaged in severe storms or being run aground on reefs. If any of those had happened to Nephi it would have quickly spelled the end of his journey. As you can see in the table below, of the 11 voyages recorded, 5 of them ended earlier than hoped due to boat or navigation issues. This lets us calculate the risk of failure, similar to how risk per mile estimates are made in the context of modern transportation safety. To make the calculation, I divided those five failures by the total number of miles travelled to get a per-mile risk associated with that sort of ocean travel. By that reckoning, the probability that a voyage would fail would be just over 1 in 10,000 for each mile traveled.

| Ship | Length (Miles) | Success? |

|---|---|---|

| Kon-Tiki | 4,300 | No |

| Seven Little Sisters I | 6,301 | Yes |

| Seven Littls Sisters II | 7,457 | Yes |

| Kantuta I | 2,323 | No |

| Kantuta II | 2,323 | Yes |

| Tahiti-Nui | 4,470 | No |

| Tahiti-Nui II & III | 5,460 | No |

| Tangaroa I | 4,576 | Yes |

| Tangaroa II | 4,300 | Yes |

| An-Tiki | 3,000 | Yes |

| Kon-Tiki II | 2,323 | No |

| Total | 46,833 | 5 failures |

| Risk/Mile | .000106762 |

Now, keep in mind that this is probably an overestimate of the risk, given that the successful voyages probably could have gone quite a bit further than their final destination. Nevertheless, given that we’re dealing with a pretty small sample size, we’re going to assume that this risk is too low, and that the real risk for this type of voyage would be double what we estimate here, at about 2 in 10,000 per mile.

Once we have that estimate, we can calculate the probability that Nephi would have survived his 17,000-mile voyage. If we assume that every mile would have an independent chance of failure, we can take the value of .000213525 (double our initial risk estimate), subtract it from 1, and then take it to the power of 17,000. That would mean that the probability of surviving that journey would be at least p = .026508. You can get a sense of how that probability changes over the length of the journey in the figure below:

Summary. With these two probabilities in hand—the probability of being able to build the boat with the available labor, and the probability of surviving the 17,000-mile voyage—we can calculate the overall consequent probability by multiplying the two values together. If you do that, you get an estimate of p = .008178. That’s a fairly low probability. It’s also far from impossible.

It’s also important to note that this probability hinges strongly on our estimates of per-mile risk of ocean travel. If we decided, for instance, not to double our risk estimate, the consequent probability would increase to p = .05. If somehow the risk is actually far greater than reflected in my list of ocean voyages, then Nephi’s chances start to sink considerably.

CA—Consequent Probability of Modern Authorship – So what should the probability be for being able to produce Nephi’s story assuming that it’s fictional? Obviously, people can make up whatever they want when producing fictional narratives, so you might think that the probability is p = 1. I think there’s a case to be made, though, that Joseph gets more right about boatbuilding and ocean travel than he should in a fictional narrative. A lot of fictional ocean-going tales are extremely fanciful affairs and, as is evident here, Joseph never strays into territory that’s completely implausible. Nevertheless, as is our habit, we’re going to give critics the benefit of the doubt on this (and many other) fronts. Our estimated consequent probability will be p = 1.

Posterior Probability

PH = Prior Probability of the Hypothesis (Our prior estimate of how likely it is that the Book of Mormon is authentic, or p = 2.41 x 10-28)

CH = Consequent Probability of the Hypothesis (The estimate of how likely it would be to build a boat and sail it to the New World, given what we know from the text and similar voyages, or p = .008178)

PA = Prior Probability of the Alternate Hypothesis (Our prior estimate of how likely is it that the Book of Mormon is a modern work of fiction, or p = 1 – 2.41 x 10-28)

CA = Consequent Probability of the Alternate Hypothesis (The estimate of how likely it would be to create Nephi’s stories within a fictional account, or p = 1)

PostProb = Posterior Probability (Our new estimate of the probability of an authentic Book of Mormon)

| PH = 2.41 x 10-28 | |

| PostProb = | PH * CH |

| (PH * CH) + (PA * CA) | |

| PostProb = | (2.41 x 10-28 * .008178) |

| ((2.41 x 10-28) * .008178) + ((1 – 2.41 x 10-28) * 1) | |

| PostProb = | 1.97 x 10-30 |

Lmag = Likelihood Magnitude (an estimate of the number of orders of magnitude that the probability will shift, due to the evidence)

Lmag = log10(CH/CA)

Lmag = log10(.008178 / 1)

Lmag = log10(.008178)

Lmag = -2

Conclusion

It’s pretty easy to see why critics would latch onto the idea that Nephi’s voyage was impossible. Most of the people reading this would likely laugh openly at the suggestion that they, themselves, would be able to build a boat and sail it across the ocean, particularly when they have in mind a Renaissance-era sailing vessel. But even conservative estimates suggest that it’s not nearly as implausible as it might seem at first glance. Assuming that Nephi had the available expertise (via revelation), he and his brothers likely had more than enough time to build a boat and would have had a fair shot at reaching the New World even in the absence of divine protection.

Skeptic’s Corner

To be fair to the critics on this one, very few of my estimates are based on hard data. It’s very hard to get a sense of things like the overall risk of ocean travel in ancient times, or how long it might have taken Nephi’s amateur crew to build a boat. There’s just too much we don’t know about the boat, about the route they travelled, about how much work they put in, or how many years they stayed at Bountiful, or any of a number of other important variables. In the end, that uncertainty is part of why this doesn’t make for great evidence against the Book of Mormon. Critics could potentially build a statistical case here that looks worse for the Book of Mormon, but it’s unlikely that such an estimate would be more reasonable or more grounded in hard data.

That said, there’s one particular thing that could change this picture somewhat, and that would be how the risk of ocean travel might change over the course of the journey. Here we’ve assumed that the risk is constant—that the risk at the first mile is about the same as the risk at the 17,000th mile. But that’s not necessarily true. It could be that the risk dramatically increases over time—that wear and tear accumulates on the boat, that supplies run low, or that cabin fever starts to set in. Projects like Hokulea show that this doesn’t have to be the case, and that if properly equipped ancient boats could stay on the water almost indefinitely. But if that risk does systematically increase, so too could the strength of this particular evidence. The problem, as with most everything else, would be in pinning down the details—at this point, those details remain slippery enough that the Book of Mormon can sail by relatively unscathed.

Next Time, in Episode 9:

When next we meet, we’ll be considering evidence from Royal Skousen and Stanford Carmack concerning the presence of Early Modern English within the Book of Mormon.

Questions, ideas, and blunt objects can be flung recklessly toward BayesianBoM@gmail.com or submitted as comments below.

Hi, Kyler. Setting the ocean voyage aside I just conducted an experiment with the help of Chat GPT regarding the translation of the Book of Mormon and the likelihood that Joseph Smith wrote the Book of Mormon himself. I found the enterprise enlightening. Although it is not connected with ocean voyages it is however, I believe, another confirmation that the BOM is true. If that is so, then all the wranglings about metals and time frames and food/water storage become irrelevant.

Is there a way to send you my PDF (62 pages). I think you will find it interesting and thought provoking.

Alan Spedding

Sounds interesting! I’d be happy to take a look. You can send it to me at bayesianbom-at-gmail.com

I love the series. I have to agree that Dr. Rasmussen bends over backwards in order to satisfy the skeptics (and they’re still not satisfied/they’re never satisfied.)

One thing is certain, ancient mariners traveled the ocean. Regardless of what the pundits have to throw about currents, iron, wood, ship, water or wind, other ancient people did it, so you just can’t say that it can’t be done. Those kind of comments just need to be thrown out, because the historical proof is already there.

On the other hand, one assumption which Dr. Rasmussen makes does not always have to go the way he indicated. For instance, when he said, “Here we’ve assumed that the risk is constant—that the risk at the first mile is about the same as the risk at the 17,000th mile. But that’s not necessarily true. It could be that the risk dramatically increases over time…” From my perspective, the opposite could also be true, that the further they travel, the more experienced, they become. The further they travel, the more skilled they become at sailing, at repairing and at finding methods and means of survival. To assume, for instance that they couldn’t stop on the journey for fresh water and other supplies when in sight of land is laughable. Why wouldn’t they? Anyway, my point is that from my perspective, the further they travel, the more likely it is that they will be successful, and therefore the risk actually goes DOWN per each succeeding mile…

Anyway, as Dr. Rasmussen states, there’s a lot we just don’t know about. Far be it from any of us to make assumptions either way and thus his willingness to err on the side of caution.

Agreed, Tim. I am really enjoying Kyler’s series also. And you are correct, the critics are never going to be satisfied. Too bad. Opening one’s mind and heart to the reality that Joseph Smith was a true prophet opens the door to a universe of wonders.

You wrote that the longer Lehi’s sea journey went on, the more successful they were likely to be. In other words, the risk of the next mile traveled is less, not greater, than the previous mile. I think that is correct.

It occurred to me that Nassim Taleb makes a very similar point in his book “Antifragile” about positive (convex) asymmetries. If you have gotten X miles along in your journey, the likelihood that you will be able to journey the next mile increases. It is not linear.

Taleb’s book is really well worth reading and has an amazing number of congruences with what scripture tells us about the world we live in.

Thank you Bruce. I was surprised but appreciative of your comment, especially as I just happened to quote you in the next segment.

I honestly believe in the veracity of the Book of Mormon. That being said and as a biased responder, I have to say that currently and from the evidence that I’ve seen, even if an angel came down from heaven and declared the Book of Mormon to be the word of God to some (maybe the majority) of these naysayers, they still would not believe.

–thus it is, but it is an unfortunate truth, none the same.

Thanks for reading Tim!

I agree that it’s possible that the risk would systematically decrease over time. If thego by the limited data we have from the Kon-Tiki and similar voyages, though, I think it might lean the other way.

If risk started out high and systematically decreased for those voyages, then we’d see most of the failures being early ones–say within the first thousand miles–with the voyages becoming less likely to fail as time went on. But that’s not what we see. Most of the failures occured several thousand miles in, which suggests either a more even risk profile, or one where risk increases over time.

Of course, Nephi’s voyage may not be comparable to these voyages at all, in which case anything goes. And I’d love to have more robust data on ancient voyages to work off of. But in the meantime, I don’t think the data point us to a scenario of decreasing risk.

Rasmussen doubts the possibility of the creation and use of iron/steel tools or parts in the construction of the Nephite ship. However, iron/steel was regularly being crafted in the Levant and Egypt for centuries before the time of Lehi & Nephi. Smelting was not required, and Nephi even states that he had a bellows — which would enable him to create an iron bloom in a clay furnace, which he could then repeatedly carburize, hammer and quench, until he had made excellent steel. The late John Tvedtnes made a strong case for Clan Lehi as rich smiths or metallurgists.

Aside from trade conducted by Phoenician and Egyptian vessels up and down the Red Sea, we know that Israelites had been trading regularly with India for centuries before Lehi & Nephi — who likely had seen such vessels.

During some years (El Niño), a reverse current runs from west to east across the central Pacific, making that part of the voyage particularly swift and easy.

Thanks for the additional information Robert. This is what I get for taking Zelph on the Shelf at their word. It would’ve indeed been possible for Nephi to shape iron in a bloom without smelting, and these processes were well in place by Lehi’s day.

Still good to know that it would’ve been possible to do the job even without the benefit of iron.

What about drinking water?

Assuming you need a gallon of drinking water per passenger per day, 40 passengers, and a 365-day voyage, they would need about 60 tons of water over the course of the voyage. Surely you aren’t suggesting they had the means to collect and store this much water for their voyage before they set sail. Once on the oceans, rain water would be sporadically available of course, but gathering and storing enough rain water on a small raft for 40 passengers has extreme hurdles in its own right.

Another hurdle you didn’t mention is wind direction—there is a reason the Kon-Tiki sailed from Peru to Polynesia rather than the other way around. That is because from 30-degrees north to 30-degrees south, the wind patterns are dominated by the *trade winds* which consistently blow from east to west. So not only are you suggesting that a group of landlubbers built a boat as fast as a team of expert Vikings could build one, but also that they sailed this boat nonstop for 17,000 miles *against the wind.*

I believe that in 600 B.C. the very best sailors in the very best vessels could have sailed a couple of thousand miles from, say, Western Africa to the New World or even from the new world to Polynesia. But the idea is simply preposterous that in 600 B.C. a group of men, women, and children from Israel decided to take a 1,500 mile walk across the desert, build an ocean-worthy ship, get on it, and sail against the wind for 17,000 miles without stopping. That didn’t happen. It is impossible.

Of course you might respond (with apologies to Westley), “Nonsense! You’re only saying that because no one ever has.” But that is the point.

That said, the hypothesis I’m considering is quite specific and I’m trying to be consistent on this point. My hypothesis is that the Book of Mormon is an accurate translation of an authentic ancient manuscript. In principle, a ludicrous story of somebody sailing around the world to establish a great civilization is equally consistent with 5th-century mythology as it is with 19th-century fiction. Because of this, I am leaving my odds unchanged.

I’m still at 1-to-4,000,000.

Thanks Billy. These are valid concerns.

So we have two potential problems here. Wind and water.

In terms of wind, you’re right that most trade winds are generally blowing the wrong way. However, as Robert points out above, the exception is the Equatorial Counter Current, which runs west to east across the equator, and would’ve been an exceptionally convenient way to get across the Pacific (and could easily land them near the southern coast of Mexico).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Equatorial_Counter_Current

In addition, the idea that it wasn’t possible to sail east is countered by the fact that ancient Asian seafarers were the ones that settled the vast majority of the Pacific, despite the occasional Peruvian contribution.

In terms of water, let’s think it through a bit.

Let’s not worry about what doctors would recommend in terms of water consumption, but in terms of what they’d actually need to survive. That turns out to be about a litre/day, not counting sweat, so to factor that in we’ll work with 2 litres for adults. When water was low, it was pretty common on the high seas for crew to be rationed down to a litre a day, though that didn’t do much to keep the peace. Children need about half to a quarter of that, but we’ll count them as needing 1 litre/day.

https://outdoors.stackexchange.com/questions/18474/what-is-the-minimum-amount-of-water-per-day-to-survive

We’ll also get a bit more specific about how many people we’re planning for here. Based on Greg Smith’s estimates, he provides a liberal estimate of 32 adults and 2 children, which would give us a requirement of 66 litres/day, or 24,090 litres over the course of the year.

In terms of how much they could’ve carried with them, we can use the Hoku’lea for a decent estimate there–for their crew of 15 they carried about 308 gallons (56 containers of 5-6 gallons). Extrapolating that to our crew of 34, we could say Nephi’s ship could carry around 698 gallons of water, or 2,792 litres. That alone would be enough for about a month and a half of the voyage. (And that’s a conservative estimate. For Heyerdahl’s Kon’Tiki crew of six they were able to carry 1,040 litres, which, extrapolated, would’ve been almost 6,000 litres, or enough for about three months.)

Could they have gotten the remaining 21,297 litres by collecting rainwater? Having served my mission in Hawaii, I can attest that, at least in tropical conditions, rainwater wouldn’t be as inconsistent as you might think. While I was there I sent my soon-to-be wife a postcard of the coastline just north of Hilo.

“Do you know why it’s so green?” I wrote. “Because it rains. All the freaking time.”

Indeed, the tropical Pacific receives on average about 200cm of rain/year. Based on that, it could be possible to put together a basin of about 10.7 x 10.7ft (or a mechanism to collect water from an equivalent surface area), and that would be enough to collect the required rainwater.

And that’s not accounting for the possibility that they did stop along the way to resupply, and that Nephi simply didn’t record the pit stops.

So over the last three posts it looks like you’re 0 for 4 in terms of identifying impossibilities. Not the best of batting averages. I’ll look forward to your next swing.

Regarding rain, “Without mountains, the Hawaiian Islands would be sparsely vegetated and dry. But because air is forced to rise as wind blows onto the windward slopes of mountains, the Islands extract about 3 times as much rain from the air as falls on the open ocean.” (https://laulima.hawaii.edu/access/content/group/dbd544e4-dcdd-4631-b8ad-3304985e1be2/book/chapter_6/lifting.htm#:~:text=Without%20mountains%2C%20the%20Hawaiian%20Islands,falls%20on%20the%20open%20ocean.)

Collecting rain water on a boat that is bouncing around in a storm is much more difficult than collecting it off of your roof.

I happen to have some experience sailing in the open ocean. When recreational sailors sail around the world, what they typically mean is that starting at, say, the Panama canal, they sail west to the bottom tip of Arabia, up red sea, into the Mediterranean via the Suez canal, then continue west back to Panama. They do this because there is a strong, reliable wind that pushes them along this route. It’s funny that you think it’s plausible that Lehi and his family sailed along 75% of this route in a primitive raft *in the wrong direction.* Suggesting that they pulled it off by drifting along El Nino currents in the doldrums is simply wishful thinking.

To make this journey possible, you have to play the Luke 1:37 card. That’s your prerogative, of course, but it illustrates the non-serious nature of this entire exercise. To get the probability of success up to 2%, you had to assume:

1- God made them expert boat builders

2- God made them expert sailors

3- God changed the winds and the currents to guide them from point A to point B

If you can assume divine intervention anytime you need to in order to get the probabilities you want, what’s the point?

” But because air is forced to rise as wind blows onto the windward slopes of mountains, the Islands extract about 3 times as much rain from the air as falls on the open ocean.”

Of course, which is why it’s a good thing I used the values for actual ocean precipitation rather than for the islands themselves.

“Collecting rain water on a boat that is bouncing around in a storm is much more difficult than collecting it off of your roof.”

Even though they weren’t really set up for it, sailing vessels in the tropics could easily collect a ton or two of water from a decent rainstorm. It would definitely be doable for Nephi to plan for and build a simple mechanism to collect rainwater, and that such water would’ve been enough to refill their water storage as they went and keep them alive.

“To make this journey possible, you have to play the Luke 1:37 card.”

Your use of the term “made” suggests something far more supernatural than I’m suggesting. God would need to have instructed Nephi on boat building and sailing (and experience would quickly have made experts of all of them), but that’s exactly what the text says happened, and, in my view, is an extremely minimal assumption in terms of what a divine being would be capable of.

“Suggesting that they pulled it off by drifting along El Nino currents in the doldrums is simply wishful thinking.”

The Equatorial Countercurrent is more than just doldrums. It’s stronger seasonally and during El Nino years, but is definable year-round and is about 300 miles wide. No metaphysical alteration of the winds or the waves would’ve been necessary to get Lehi to the New World.

If they dropped down to the Roaring forties the wind would have been the proper direction. That could have taken them all the way to the South Pacific high pressure system which would then spit them out in the current that leads directly to Central America.

Thanks Rodney! This would’ve lengthened the trip quite a bit (which would mean increasing my risk calculation), but that would be a definite possibility.