Intro/FAQ ⎜ Episode 1 ⎜ Episode 2 ⎜ Episode 3 ⎜ Episode 4 ⎜ Episode 5 ⎜ Episode 6 ⎜ Episode 7 ⎜ Episode 8 ⎜ Episode 9 ⎜ Episode 10 ⎜ Episode 11 ⎜ Episode 12 ⎜ Episode 13 ⎜ Episode 14 ⎜ Episode 15 ⎜ Episode 16 ⎜ Episode 17 ⎜ Episode 18 ⎜ Episode 19 ⎜ Episode 20 ⎜ Episode 21 ⎜ Episode 22 ⎜ Episode 23

[Editor’s Note: This is the sixteenth in a series of 23 essays summarizing and evaluating Book of Mormon-related evidence from a Bayesian statistical perspective. See the FAQ at the end of the introductory episode for details on methodology.]

The TLDR

It seems unlikely that an ancient book would have so many themes and ideas common to the early nineteenth century.

Most critics will be quick to point out that the Book of Mormon contains elements that correspond to nineteenth-century religious and cultural thinking. These range from its talk of liberty and freedom to its well-developed theology of the fall, the atonement, and the resurrection. Though these ostensibly modern themes should give us pause, they’re accompanied by a number of themes and literary practices that have strong parallels in the ancient world. Weighing these two sets of themes side-by-side, we’re able to give an advantage to the critics, with the probability of seeing such modern themes in an ancient text estimated at p = .00001.

Evidence Score = -5 (reducing the likelihood of an authentic Book of Mormon by five orders of magnitude)

The Narrative

When we last left you, our ardent skeptic, you had awoken from the second rather haunting dream, though now it appears that you’re awake for good. You slowly climb off your straw mattress, and after a brief but creaky stretch, you stick your head out into the chilly morning air. The sky is a fantastic blue and the sun streams with increasing brightness against the rough logs of your cabin. There would normally be work to do on such a morning, but you do little to resist the urge to come back inside. After taking a moment to relight the fire in your hearth, you sit back down at your table, where the increasingly intriguing book awaits you.

Despite what you’d experienced the last few days, you still can’t bring yourself to accept that such a book could be authentic, or that its author could be the prophetic figure he’s purported to be. There must be something that you had been missing, and with each turn of a page you become more sure that it’ll turn up. You read ravenously, though your reading seems to be dominated by wars, other wars, and yet more wars. You have to admit feeling a little tug on the heartstrings as you read about the martyrdom of a certain Abinadi, and you’re entertained somewhat by the missionary exploits of a man named Ammon and his brothers, but as the hours pass you try not to get too distracted by such tall tales.

Your stomach eventually lets you know that it’s time to take a break, but you can’t help but press on just a little further. You are slogging through yet another war when you happen to run across a rather interesting passage about a group of young men who take up arms in place of their fathers, who had made an oath against violence. One particular verse catches your eye:

And they entered into a covenant to fight for the liberty of the Nephites, yea, to protect the land unto the laying down of their lives; yea, even they covenanted that they never would give up their liberty, but they would fight in all cases to protect the Nephites and themselves from bondage.

Hmm, you think to yourself. Fighting for liberty. What an American thing to say.

That idea jogs your memory, and you quickly turn back a few pages, trying to find another verse that had briefly held your attention:

And it came to pass that this matter of their contention was settled by the voice of the people. And it came to pass that the voice of the people came in favor of the freemen, and Pahoran retained the judgment-seat, which caused much rejoicing among the brethren of Pahoran and also many of the people of liberty, who also put the king-men to silence, that they durst not oppose but were obliged to maintain the cause of freedom.

A people settling political differences through some sort of democratic process? And doing so to fight for the sake of freedom against the oppressive specter of monarchy? The idea seemed like it could belong only to someone who grew up reading about the heroic exploits of Washington or Hamilton in the Revolutionary War. You even recall reading somewhat earlier about a righteous king deciding to forsake his crown, setting up what appeared to be a representative republic staffed by “judges.” How very convenient for these ancient peoples to align themselves so strongly with American values and political structures.

As you prepare and eat your lunch, you wonder what other decidedly modern themes you might notice in the book, now that you knew to look for them. Regardless, it seems unlikely that an authentic ancient book would have so many themes and ideas common to the early nineteenth century.

The Introduction

It’s a common refrain from critics of the Book of Mormon that the book is filled with the telltale fingerprints of nineteenth-century religious and political culture. According to these critics, not only does the book include anachronistic references to Christ, as well as direct quotations of the New Testament, but these supposedly ancient prophets place a distinctly reformation-based stamp on core Christian doctrines. These critics also find parallels to what are assumed to be thoroughly American ideas, ranging from democracy to republican representation to anti-masonic sentiments. And the evidence at their disposal is often quite compelling, convincing even some faithful scholars, such as the prolific Blake Ostler, that Joseph Smith had to be personally responsible for at least some of the content of the book.

But to count these themes as evidence against the authenticity of the book, it’s important to weigh them against thematic elements that appear to point to ancient origins. Faithful scholars have dug up an impressive array of ancient themes and literary structures within the book that seem out of place in a nineteenth-century forgery. Though we’ve covered some of these in a previous episode, we’ll be using several others as a counterweight to the supposedly modern ideas within the Book of Mormon. If modern themes suggest a modern book, ancient themes should suggest an ancient one.

The resulting analysis will look a great deal like what we’ve done previously with the book’s archaeological evidence. Though each theme on either side is deserving of close and attentive analysis, I’ll be doing my best to provide a high-level summary, giving each a rough weight in terms of how specific, detailed, and unusual each of these parallels are, hopefully providing a sense of what that evidence will allow us to conclude about the book’s authenticity.

The Analysis

The Evidence

Before we get into what these themes are, we’ll need to answer a couple of key questions. What, pray tell, is a theme? And what counts as a parallel?

I can’t claim any special expertise in answering those questions—feel free to chat up your friendly neighborhood humanities professor for an in-depth discussion—but my focus is on being able to capture useful markers that could tie the text to ancient or modern time periods. We certainly aren’t going to be using the usual definition of theme as the underlying message of a text. If you’re interested in that level of analysis, I’ll refer you to this lovely article from Terryl Givens.

We’ll also be going a bit beyond the dictionary definition of theme, as the subject or topic of a text. A lot of the nineteenth-century points raised by critics would fit under this umbrella, but the faithful side has a number of interesting proposals that went substantially deeper than either the surface-level subject or even the underlying message. These ancient characteristics had to do with the base structure of the text itself, things like how King Benjamin’s discourse follows a well-documented biblical pattern for renewing covenants, or how Samuel’s blistering rebuke of the Nephites follows the distinctive format of a prophetic lawsuit. These aren’t “themes” per se, but they are nevertheless potential markers of ancient literary practice, and I included them in the analysis.

In terms of what would count as a parallel, I tried not to pass much judgment, and to instead rely on what critics and faithful scholars brought forward as aligning with nineteenth-century or ancient thought or practice. A substantial resource in helping to suss those out was a Dialogue article by Blake Ostler, where he tried to forge a middle path arguing for both ancient and modern influence on the text. He was pretty motivated to marshal as much compelling evidence as possible on both sides, since both essentially supported his argument. This was supplemented with a manual search and a review of some additional sources, including a summary produced by Royal Skousen at a recent talk discussing nineteenth- (and sixteenth-) century themes in the Book of Mormon text.

The result was a list of 25 modern and 14 ancient themes. I’ve included these below, each with a brief description. That material represents the evidence we’ll be working with for the purposes of this analysis.

| Nineteenth-Century Themes | Summary |

|---|---|

| Democracy | Several examples in the Book of Mormon are acclaimed by the “voice of the people”. Bushman makes a strong argument that both Nephite and American democratic forms are quite specific and the details don’t match. |

| Republican governmental forms | Mosiah’s system of judges bears some resemblance to republican representation. Bushman makes a strong argument that both Nephite and American forms of republican representation are quite specific and the details don’t match. |

| Anti-monarchical sentiment | As Bushman describes, the anti-monarchical sentiment shown in nineteenth-century America is broadly present in the Book of Mormon (seen most clearly in Mosiah 23), and the details, though sparse, don’t directly contradict nineteenth-century themes. But the sentiment also matches very well with how monarchical forms are portrayed in the Old Testament. |

| Egalitarianism | The Book of Mormon includes egalitarian themes in the narrative of 4th Nephi, and statements decrying “inequality” among the people. The details, when provided, broadly align with communal Protestant sects. It also matches the communal nature of early Christianity. |

| Free-masonry | This common charge is generally tied to Book of Mormon descriptions of “secret combinations”. As described by Greg Smith, the label of "secret combinations" was used for a lot more even in the nineteenth century than as a label for masonry. The details of secret combinations are provided in the Book of Mormon, and they are a much better match for how ancient robber-bands operated than for masonry (see also p. 73-76 of Ostler). |

| American revolution | 1 Nephi 13 describes an apparent prophecy of the American Revolution (though it could apply more broadly as well). However, as Bushman notes, there is no actual description of the violent overthrow of an established monarchy in the Book of Mormon, and the Book of Mormon is absent the heroic narratives that characterized American literature. |

| Infant baptism | The harsh critique of infant baptism found in the Book of Mormon does match similar nineteenth-century critiques in form and detail, though it was also critiqued by early Christian authors, notably Tertullian. |

| Ordination and authority | The practice of ordination in the Book of Mormon broadly matches Protestant practices, though it’s also consistent with Hebraic and early Christian practices. |

| Trinitarianism | The description of the Godhead presented in the Book of Mormon (e.g., by Abinadi) does appear to follow relatively late Christian language applied to the Trinity. Though there are interesting discussions about what kind of trinitarian conception is presented in the Book of Mormon, it would definitely have been unusual in a pre-Christian Hebraic context. |

| Regeneration | The idea that baptism is salvific would have been very unusual in a pre-Christian Hebraic setting, and the details provided in the Book of Mormon align with a more advanced Christian theology. |

| Repentance and penance | The Book of Mormon does preach the need for repentance. Repentance has been a common theme in all ages of biblical and pre-biblical thought, and the details provided don’t match a Protestant or Catholic conception of repentance (e.g., the need for private confession). |

| Justification | Justification through faith and good works is a present theme in the Book of Mormon, and the details of it don’t generally contradict nineteenth-century Protestant theology, though the doctrine wasn’t foreign to biblical Jews prior to the exile. |

| The Fall | Lehi provides an advanced understanding of Adam’s fall. The doctrine of the fall is generally absent from the Old Testament outside the Genesis narrative itself. Its origin is arguably pre-Christian, though not pre-exilic. |

| The atonement | The idea that Christ would atone for the sins of the world, as commonly found in the Book of Mormon, is difficult to read into a pre-exilic context (though it’s not entirely impossible). These sorts of details would probably require revelation on the part of Book of Mormon prophets. |

| Transubstantiation | This theme doesn’t actually exist in the Book of Mormon. Alexander Campbell was smoking something particularly strong when he posited this one. |

| Fasting | The Book of Mormon does show the practice of fasting. Fasting has been a common biblical and extra-biblical religious practice, and isn’t at all out of place in the Book of Mormon. |

| Church government | The ordination of priests and apostles in the Book of Mormon exists, but doesn’t appear to align coherently with Protestant ideas in any detailed way, and it was obviously present to some extent in early Christianity. |

| Religious experience | Pentecostal experiences are described in a limited fashion in the Book of Mormon, but are not out of place in an early Christian or even a Hebraic context. |

| General resurrection | As summarized by Ostler (p. 82), the idea of a general resurrection is well-developed in the Book of Mormon, and would have been unusual in a pre-exilic Israel (though there is some debate on that front). |

| Eternal punishment | As summarized by Ostler (p. 83), the idea of an after-life as presented in the Book of Mormon wasn’t a general belief among pre-exilic Jews, though the basic ideas would have existed and are present at certain spots in the Old Testament. |

| Lionizing of Columbus | The Book of Mormon prophesies of Columbus several thousand years before his birth. |

| Anti-Catholicism | Though many faithful today would take issue with the idea that 1 Nephi 13-15 contain anti-Catholic sentiments, the ideas presented do appear to align with nineteenth-century anti-Catholic literature. |

| Independence of church and state | The Book of Mormon does seem to show a separation of the church from the mechanism of the state, and this idea would have been quite unusual in ancient context, (though the seeds of the idea can be traced to as early as Augustine). The details, however, do not appear sufficient in the case of the Book of Mormon to draw a firm parallel. |

| New Testament quotations | Despite the possibility that the quotations and allusions are the result of the same translation process that produced the book’s Early Modern English, it’s hard to deny that finding these quotations is unusual in a purportedly ancient book. |

| Racism | The Book of Mormon’s characterization of racial issues does in some ways appear to mirror racial issues in nineteenth-century America, though this kind of racism would not have been unusual in the ancient world. |

| Ancient Themes | Summary |

| Tree of Life | Though critics would look to the dream of Joseph Smith Sr. as the primary source for Lehi’s dream, there are many more details in it corroborated by ancient texts and symbolism than are recounted by Joseph’s father, including similarities to the Narrative of Zosimus, Nephi’s connecting of the tree to the divine feminine, and the inclusion of the river of filthy water, which was a common ancient symbol for hell. |

| Covenantal formulary | The sermon of King Benjamin follows a specific ancient literary structure called a covenantal formulary, and uses a form appropriate for a Judaism stemming from Lehi’s day. |

| Pre-exilic wisdom traditions | As detailed by Margaret Barker, there are a number of details in the Book of Mormon that point to a pre-exilic theology and practices, particularly references to the pre-reform wisdom tradition. |

| Apocalyptic structure | 1 Nephi 11-14 follows the same pattern as examples of ancient apocalyptic literature, and in ways separate from biblical examples of apocalyptic styles. |

| Prophetic lawsuits | The structure of the Lamanite prophet Samuel’s rebuke of the Nephites includes detailed elements of a "prophetic lawsuit" as engaged in by biblical prophets. |

| Cosmic worldview | The Book of Mormon generally follows a cosmic worldview, with the elements seen as obeying God’s commands, generally more so than do humans. |

| Setting hearts on riches | The idea of treasures becoming slippery or disappearing, as described in the Book of Mormon, has strong parallels to the ancient Near East, such as with the Egyptian Instruction of Amenemope and in the Book of Enoch. These parallels go beyond similar thoughts posed in Proverbs, and are much stronger than money-digging parallels proposed from the early nineteenth century. |

| Olive tree allegory | The use of the olive tree as a metaphor for Israel is authentically ancient, and the details of olive horticulture are remarkable coming from a New England farm-boy. |

| Jacob’s rent garment | The idea that there was a remnant of the patriarch Joseph’s garment (i.e., the coat of many colors), and that it held special religious significance, can be traced to ancient sources, and have no parallel in Joseph Smith’s day. |

| Messiah ben Joseph | The Book of Mormon references an echo of ancient rabbinic traditions regarding a Messiah who would come through the line of Joseph, who would restore temple traditions, would be associated with the return of Elijah, and would be killed in combat with the enemies of God. That these traditions would also show remarkable parallels to Joseph Smith’s own life is startling. However, ideas regarding "Messiah ben Joseph" were known and discussed in Christian sources in Joseph’s day. |

| Prophetic commissions | Lehi’s call as a prophet in 1 Nephi 1 takes the form of an anciently-derived prophetic commission and includes a throne theophany. These structures are biblical and were starting to receive critical attention in Joseph’s day. |

| Israelite law | There are numerous examples of details in the Book of Mormon matching the particulars of Israelite legal practice. Though many of these details are biblical, some are extrabiblical (e.g., the felling of trees on which someone had been hanged). |

| Sacred south and profane north | Ostler (p. 100) maintains that the identification of Desolation in the North and Bountiful in the South correspond with ancient themes of a "profane north" and a "sacred south". |

| Subscriptio | Joseph Smith stated that the title page of the Book of Mormon came from the last leaf of the gold plates, corresponding with the ancient practice of subcriptio, common in Greek and Mesopotamian literature. |

The Hypotheses

How that evidence might be accounted for is another matter. We’ll be going with two main hypotheses for this analysis, each being required to explain the opposite kinds of evidence:

Nineteenth-century themes in the Book of Mormon can be explained by chance, convergence, and revelation—Under this theory there are a few ways that apparent nineteenth-century themes could arise, and these mechanisms could apply differently (or in some combination) for each of those themes.

The first of those mechanisms is chance, in that the details of the Book of Mormon and nineteenth-century American culture just happen to look similar and bear no other particular connection. The democratic and republican elements of Book of Mormon government would be a good example here—the Book of Mormon describes a variety of governments, and some of those would be expected to show surface similarities to American forms on the basis of chance alone. Of course, chance becomes less likely of an explanation the more the details of the themes match, and how unusual those characteristics are. Some of the more specific and detailed themes appear to require a better explanation.

One better explanation might be the idea of convergence—we see this idea in the context of evolution, where a common environment and common needs lead organisms to develop similar adaptations. For example, you might have organisms in dark environments living continents apart that both evolve the same mechanisms for dealing with the dark, such as bioluminesence. Those similar mechanisms wouldn’t be a marker that those species were related, just that they had to solve the same problems and evolved the same mechanisms to deal with the problem. I could see something similar occurring in theology, where similar theological problems could tend to produce similar theological solutions.

Take, for example, the issue of salvific baptism. As soon as the idea is introduced that baptism is required for salvation, you immediately run into the problem of what to do with baptizing children. Do children need to be baptized by immersion? If so, how do you do that without risking their premature death? If baptism is a covenant, are little children capable of making that covenant? These are valid questions, and they represent ones that would likely arise anywhere the concept of immersive baptism came about. Accepting the assumption that Christ introduced the doctrine in both the Old and New worlds, it wouldn’t be surprising for the same questions and arguments about infant baptism to arise in both areas, and for arguments for and against to take a similar shape. The same might apply to many of the other similarities between the Book of Mormon and reformation-era theology, from elements of an afterlife to atonement theology to trinitarianism.

But even that isn’t sufficient to explain all of the themes and ideas within the nineteenth century. Some of them require information to have been revealed by God to the ancient authors of the book. In some cases the Book of Mormon itself claims specific revelatory experiences (e.g., Nephi’s vision of the American Revolution and the arrival of Columbus; Alma’s answer to his inquiry on the nature of the afterlife), but revelation is still possible even in cases where the specific source of that knowledge isn’t made clear. This might include Lehi’s prescient understanding of the Fall and Abinadi’s advanced theology on the atonement.

Between chance, convergence, and revelation, none of the nineteenth-century themes are entirely without explanation from a faithful perspective. The question is whether we’re willing to swallow the assumptions and likelihoods that accompany them.

The ancient elements in the Book of Mormon can be explained by chance, common archetypes, and advanced biblical adaptation—This hypothesis, on the other hand, is associated with the idea of modern authorship, and assumes that all of the content in the Book of Mormon came from Joseph Smith or his close compatriots. In this case, chance could still be operative, as similarities between a fraudulent Book of Mormon and ancient patterns and ideas could arise purely due to happenstance, though such chance would still decrease as the number of specific and unusual parallels increase.

That chance could be assisted somewhat by the reliance of both ancient and modern sources on common religious and cultural archetypes—archetypes such as the Tree of Life, which has been used as an important symbol in a number of cultures. These symbols and archetypes have not necessarily arisen by chance, but through a common set of human patterns of meaning and myth making. Still other ancient themes can be found (though are well-hidden) in the Bible, and it’s possible that a deep and intuitive understanding of biblical narratives could have allowed Joseph to replicate them in the Book of Mormon text. This latter possibility would become less likely the deeper and more subtle those structures become.

Another potential option could be added alongside our primary hypotheses—the idea that the Book of Mormon is a blending of authentically ancient and authentically modern concepts. For Ostler, there was a Moroni and a Nephi, but a substantial portion of the content attributed to them represents a creative expansion by Joseph. That idea requires Joseph to have had substantial control over the text. A more recent version of this theory has been put forward by Skousen, who feels, based on the pervasive presence of Early Modern English in the book, that Joseph did not have control over the text beyond reading the words that were provided through the translation instruments. What he posits instead is that the modern elements (including the New Testament quotations) are creative (and potentially subtle) alterations, not by Joseph or any other nineteenth-century source, but by the ultimate translators, whoever they may be. These translators, being attuned to the language of the Early Modern era, could have also been attuned to the Reformation theology associated with that same era, helping to explain the theological parallels. He provides several other interesting examples of themes associated with the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries to help support his point.

That third way is very much a live option, I think, but I don’t see it as strictly necessary to account for the evidence as it stands—for the purposes of this analysis it would be functionally equivalent to the theory of ancient authorship, so for the moment we’ll be setting it aside.

Prior Probabilities

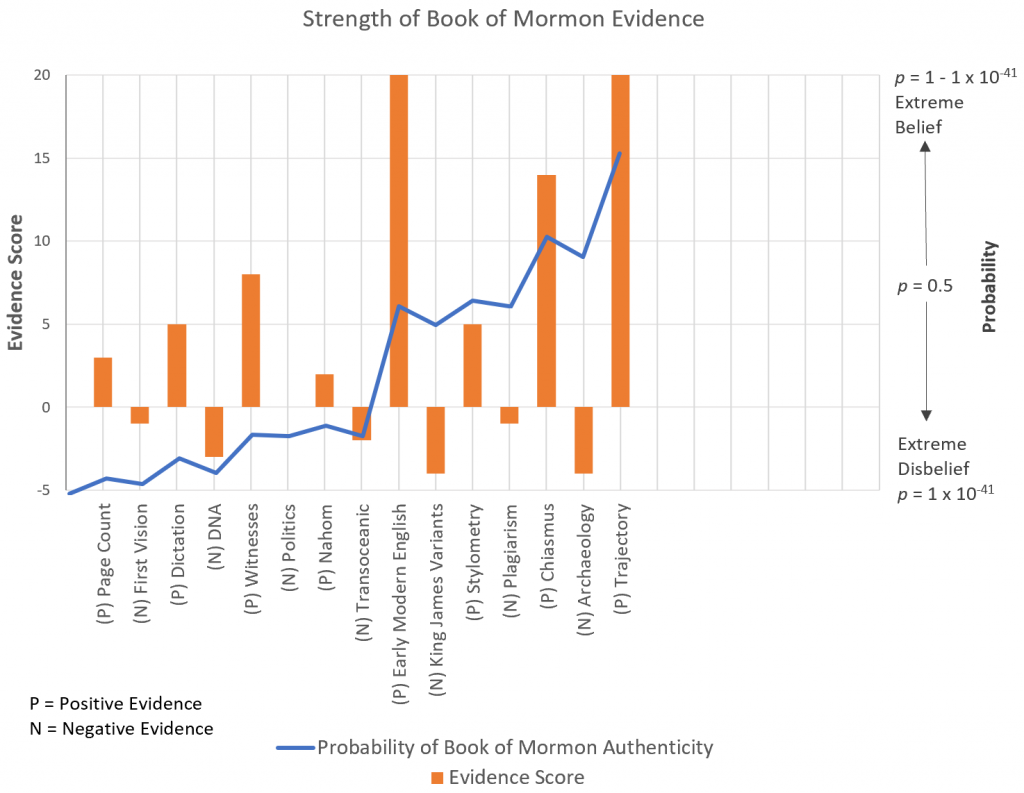

PH—Prior Probability of Ancient Authorship—As is always the case, our prior probability will be what we left off with in our last episode, based on all the evidence we’ve considered thus far, which is standing at p = 1—1.08 x 10-26. You can get a sense of how strong that evidence has been in the figure below.

PA—Prior Probability of Modern Authorship—That would leave the remainder of the probability being allotted to the critical perspective, which would be p = 1.08 x 10-26.

Consequent Probabilities

Since we’ll be using the same methodology that we applied a couple episodes ago, as well as in prior literature, all that now remains is to make a series judgements regarding each piece of evidence: whether a correspondence can be specified between the Book of Mormon and nineteenth-century literary themes (i.e., the correspondence is specific), whether those specifics include notable details beyond a vague description (I.e., the correspondence is detailed), and whether those details would or would not also be common to the ancient world (I.e., the correspondence is unusual). We can then assign rough probabilities for observing that correspondence in each case—p = .5 for ones where a correspondence can be specified, p = .1 for correspondences that included notable details, and p = .02, or 1 in 50, for ones that were specific, detailed, and unusual. These probabilities were offset with inverse values for any identified correspondences to ancient literary themes and practices, multiplying the overall probability by 2, 10, and 50 where correspondences between the Book of Mormon and Mesoamerican society were specific, detailed, and unusual.

I went ahead and made these judgments (you can find the full set in the appendix), along with the rationale behind each judgment. Multiplying all of these together results in an overarching estimate of the probability of the Book of Mormon being an ancient document, and it will let us produce the consequent probability estimates below.

CH—Consequent Probability of Ancient Authorship—Taking stock of the 25 different nineteenth-century themes, I determined that 7 of them should not actually be counted as either specific, detailed, or unusual, and for a variety of reasons in each case. Some of them, based on the cogent arguments of Richard Bushman, were shown to have details that were a much better match for the ancient world than the nineteenth century. Others were sufficiently vague and common in all forms of Judeo-Christian tradition, such as the ideas of repentance and fasting. Others, such as transubstantiation, don’t actually exist, despite the allegations of critics. These items were assigned a probability of 1, and didn’t count for or against the Book of Mormon.

Two of the themes were judged to be specific, but not detailed or unusual. These include specifying priests and apostles within the governmental structure of the church, and the inclusion of Pentecostal religious experiences. The Book of Mormon doesn’t provide enough detail on either of these matters to draw more than a vague parallel. These items were assigned a probability of .5. An additional 8 were judged to be specific and detailed, receiving a probability of .01. These include ones where the details of the correspondence matched, but similar forms could also be found in the ancient world, such as anti-monarchical sentiment, egalitarianism, justification through faith and good works, racism, or the idea of an afterlife.

The remaining 8 items were judged to be specific, detailed, and unusual, and received the lowest possible probability of .02. These include themes where the details of the correspondence are striking, and for which no ancient alternatives can be readily found. The Book of Mormon gives substantial doctrinal detail to the subjects of trinitarianism, baptism, the fall, the atonement, and resurrection, and in each case these details align with the religious doctrines that Joseph would have heard preached in the churches of his day. From what I was able to tell, however, they would not have been part of an ancient Judaic or early Christian understanding of these doctrines. The presence of these ideas in the Book of Mormon is a definite oddity that requires more fulsome explanations. And, if we’re not taking into account revelation, we would also have a difficult time accounting for prescient views on Columbus, direct New Testament quotations, and what appears to be anti-Catholic sentiment in the visions of Nephi.

All told, we can calculate a rough estimate for observing these themes in an ancient document at p = 6.4 x 10-23. On their own, these items would likely count as a critical strike against the authenticity of the Book of Mormon.

CA—Consequent Probability of Modern Authorship—But these items aren’t on their own–they’re accompanied by a number of themes that themselves appear genuinely ancient. In contrast with the list of modern themes, only one of the 14 ancient themes or practices I’ve included in this list was assigned a probability of 1, and that’s the idea presented by Ostler that the juxtaposition of Bountiful and Desolation align with the Sacred South and Profane North common within ancient symbology. As interesting as that idea is, the concrete nature of Book of Mormon geography leads me to write it off as a coincidence. Bountiful and Desolation don’t need to be symbolic of good and evil any more than New York and New Jersey, or San Francisco and San Diego, or Salt Lake and Provo, however well we might be tempted to think the symbol applies to the latter.

As for why there aren’t more lackluster correspondences overall, it’s not for a lack of potential candidates. There were a number of purportedly ancient themes that never even made my initial cut, and I didn’t feel it was necessary to be as exhaustive of themes supportive of the Book of Mormon as I was for those that worked against it. In fact, it’s this key slant that represents how I’m taking an a fortiori approach in this analysis. I could have spent the better part of a year reading through every KnoWhy, sweeping every FARMS Review, and combing every line of Nibley’s Lehi in the Desert, and come out the other side with a much longer list of ancient themes. But my own lack of time and resources provides for a useful handicap against the Book of Mormon and means we won’t be using the same sensitivity analyses that we used in the episode addressing archaeological issues.

There were 7 items that I judged as being specific and detailed, though not unusual. These include themes that have some form of biblical parallel, such as the covenantal formulary or prophetic lawsuits or prophetic commissions, as well as items that were being commonly discussed in Joseph’s day, such as the idea of a Messiah ben Joseph. These items were given a weight of 10. That left 6 items that I felt were specific and detailed, and that would have been both went beyond the available biblical content and that would have been unusual in Joseph’s day. These include the exceedingly detailed ancient symbology in the vision of the Tree of Life, the inclusion of authentic pre-exilic traditions, including wisdom symbology, the apocalyptic structure of Nephi’s visions, the specific language used when discussing slippery or disappearing treasures, the rich symbolism and horticultural detail in the olive tree allegory, and the strong web of correspondence between Nephite and Israelite legal practices. These six received the maximum weight of 50.

Together, these items multiply to equal 2.0 x 1017, but for the purposes of generating our consequent probability of modern authorship, we’ll be taking the inverse of 2.0 x 1017, or p = 6.4 x 10-18, which represents a rough estimate of the probability of observing these ancient themes in a nineteenth-century text.

Posterior Probability

And with that, we can complete our analysis.

PH = Prior Probability of the Hypothesis (our initial estimate of how likely it is that the Book of Mormon is an ancient text, based on the previous estimate considered, or p = 1—1.08 x 10-26)

CH = Consequent Probability of the Hypothesis (the estimated probability of observing our set of nineteenth-century themes in an ancient text, or p = 6.4 x 10-23)

PA = Prior Probability of the Alternate Hypothesis (our initial estimate of the likelihood that the Book of Mormon is a modern forgery, or p = 1.08 x 10-26)

CA = Consequent Probability of the Alternate Hypothesis (the estimated probability of observing our set of ancient themes in a nineteenth-century text, or p = 6.4 x 10-18)

PostProb = Posterior Probability (our new estimate of the probability of an authentic Book of Mormon)

| PH = 1 — 1.08 x 10-26 | |

| PostProb = | PH * CH |

| (PH * CH) + (PA * CA) | |

| PostProb = | (1 — 1.08 x 10-26 * 6.4 x 10-23) |

| ((1 — 1.08 x 10-26) * 6.4 x 10-23) + ((1.08 x 10-26) * 6.4 x 10-18) | |

| PostProb = | 1 — 1.08 x 10-21 |

Lmag = Likelihood Magnitude (an estimate of the number of orders of magnitude that the probability will shift, due to the evidence)

Lmag = log10(CH/CA)

Lmag = log10(6.4 x 10-23/6.4 x 10-18)

Lmag = log10(.00001)

Lmag = -5

Conclusion

This result should be pretty reminiscent of the result of our previous Bayesian analysis on archaeological issues. What we have with these ancient and modern themes is yet another front in a scholarly battleground that has seen plenty of crossfire but with little if any movement in the front line. As compelling as many of the critics’ points might be, they aren’t enough to dramatically outweigh or overwhelm the evidence for ancient literary influence, though it represents the strongest negative evidence we’ve considered thus far.

But since this is an exercise in thoughtful consideration of the available evidence, we should be open to hearing what the evidence is telling us. What we see in the Book of Mormon is a text with a conglomeration of thematic influences which present real explanatory challenges for both critics and the faithful. The correspondences to modern (or at least early modern) religious thinking may not be adequately dispensed with by relying on the forces of chance, correspondence, or even revelation. A ready solution to that puzzle may never be available to us, but it should encourage us to be more comfortable with the strangeness that a nuanced belief in the Book of Mormon requires. This is a strange book–it came to us in a strange fashion, and it has features that confuse and confound. Whether we deal with that strangeness in the manner of an Ostler, a Skousen, or an ostrich is our own choice. But for now, the modern does not overwhelmingly outshine the ancient, nor does the odd override the authentic.

Skeptic’s Corner

As I’ve already noted in a previous episode, I’ve opted not to drastically handicap the faithful perspective, as I did for the archaeological evidence, and as I will do again for the Book of Abraham evidence. This, again, stems from what I see to be the more even playing field for this kind of thematic evidence, which is substantially more subjective than the archaeological evidence. Skeptics could indeed insist that we handicap this evidence the same way, in which case the critical side would be strengthened considerably (evidence score of around 12 if all the critical evidence with weights lower than 1 became .02; around a 19 if all the faithful evidence is given a weight of 2), though they would land shy of the mark of a critical strike in the critics’ favor. It’s important to keep in mind, though, that critics making this case would be obliged to favor the faithful side of the argument, so such handicapping would likely be beside the point.

It’s also quite possible that I’m missing a number of important critical arguments. I tried to be as exhaustive as I could using the time I had (and I don’t believe I left too many stones unturned—faithful scholars are generally good at giving attention to the strongest critical arguments), but any additional piece of modern evidence would obviously strengthen the critics’ case. If anyone has any other pieces of evidence that they feel should be considered, feel free to throw me an email.

Lastly, there remain a number of concerns that I have with this method in general that just can’t be fully escaped. To restate something I said last time, this is not the ideal way to weigh large, complex sets of competing evidence. But it is the best bad way currently available to us. One of the things that makes it bad is only having three potential weights for each piece of evidence. There are quite a few here on both sides that could be much stronger than .02 or 50 on further inspection. Another issue is the necessary assumption that each piece of evidence is independent of each other, and this problem could potentially impact both sides. Give Joseph expertise on pre-exilic literary forms and religious concepts, and all of a sudden a bunch of faithful evidence falls by the wayside. On the other hand, give Alma or Abinadi revelatory access to reformation-era theology (or find a common source for that theology, or allow for an Early Modern translator to have shaped its presentation in the text) and the critical side almost completely falls over. I’m not going to hold my breath waiting for that kind of breakthrough, but such thoughts should lead all sides to be appropriately cautious about what this evidence ultimately brings to the table.

Next Time, in Episode 17:

When next we meet, we’ll be taking a look at the geographic details contained in the Book of Mormon and consider what it might take for a fictional work to keep that geography consistent throughout the text

Questions, ideas, and thieves in the night can be sent to BayesianBoM@gmail.com or submitted as comments below.

Appendix

| # | Time | Theme | Specific | Detailed | Unusual | p | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Modern | Trinitarianism | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0.02 | The description of the Godhead presented by Abinadi does appear to follow relatively late Christian language applied to the Trinity. Though there are interesting discussions about what kind of trinitarian conception is presented in the Book of Mormon, it would definitely have been unusual in a pre-Christian Hebraic context. Specific, detailed, and unusual. |

| 2 | Modern | Regeneration | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0.02 | The idea that baptism is salvific would have been very unusual in a pre-Christian Hebraic setting, and the details provided in the Book of Mormon align with a more advanced Christian theology. Specific, detailed, and unusual. |

| 3 | Modern | The Fall | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0.02 | The doctrine of the fall is generally absent from the Old Testament outside the Genesis narrative itself. It’s origin is arguably pre-Christian, though not pre-exilic. Having it as developed as we see in Lehi’s words is unusual. Specific, detailed, and unusual. |

| 4 | Modern | The atonement | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0.02 | The idea that Christ would atone for the sins of the world is difficult to read into a pre-exilic context (though it’s not entirely impossible. These sorts of details would essentially require revelation on the part of Book of Mormon prophets. Though this revelation is stated to have been present, there’s no way to frame it other than specific, detailed, and unusual. |

| 5 | Modern | General resurrection | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0.02 | As summarized by Ostler, the idea of a general resurrection is well-developed in the Book of Mormon, and would have been unusual in a pre-exilic Israel (though there is some debate on that front). Specific, detailed, and unusual. |

| 6 | Modern | Lionizing of Columbus | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0.02 | Prophesying of Columbus several thousand years before his birth has to be counted as specific, detailed, and unusual. |

| 7 | Modern | Anti-catholicism | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0.02 | Though many faithful today would take issue with the idea that 1 Nephi 13-15 contain anti-Catholic sentiments, the ideas presented do appear to align with nineteenth-century anti-Catholic literature, and would have been unusual in an ancient context. |

| 8 | Modern | New Testament quotations | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0.02 | Despite the possibility that the quotations and allusions are the result of the same translation process that produced the book’s Early Modern English, it’s hard to deny that finding these quotations is unusual in a purportedly ancient book. Specific, detailed, and unusual. |

| 9 | Modern | Anti-monarchical sentiment | Yes | Yes | No | 0.1 | As Bushman describes, the anti-monarchical sentiment shown in nineteenth-century America is broadly present in the Book of Mormon, and the details, though sparse, don’t directly contradict nineteenth-century themes. But the sentiment also matches very well with how monarchical forms are portrayed in the Old testament. Specific and detailed, but not unusual. |

| 10 | Modern | Egalitarianism | Yes | Yes | No | 0.1 | The Book of Mormon includes egalitarian themes, and the details, when provided, broadly align with communal Protestant sects. It also matches the communal nature of early Christianity. Specific, detailed, but not unusual. |

| 11 | Modern | Infant baptism | Yes | Yes | No | 0.1 | The harsh critique of infant baptism found in the Book of Mormon does match similar nineteenth-century critiques in form and detail, but was also critiqued by early Christian authors, notably Tertullian. Specific, detailed, but not unusual. |

| 12 | Modern | Ordination and authority | Yes | Yes | No | 0.1 | The practice of ordination in the Book of Mormon broadly matches Protestant practices, but is also consistent with early Christian practices. Specific and detailed, but not unusual. |

| 13 | Modern | Justification | Yes | Yes | No | 0.1 | Justification through faith and good works is a present them in the Book of Mormon, and the details of it don’t generally contradict nineteenth-century Protestant theology, but the doctrine wasn’t foreign to biblical Jews prior to the exile. Specific, detailed, but not unusual. |

| 14 | Modern | Eternal punishment | Yes | Yes | No | 0.1 | As summarized by Ostler, the idea of an after-life wasn’t a general belief among pre-exilic Jews, though the basic ideas would have existed and are present at certain spots in the Old Testament. The details of the Book of Mormon are consistent with nineteenth-century theology, but we won’t count them as unusual. |

| 15 | Modern | Independence of church and state | Yes | No | Yes | 0.1 | The Book of Mormon does seem to show a separation of the church from the mechanism of the state, and this idea would have been quite unusual in ancient context, (though the seeds of the idea can be traced to as early as Augustine). The details, however, do not appear sufficient in the case of the Book of Mormon to draw a firm parallel. Specific and unusual, but not detailed. |

| 16 | Modern | Racism | Yes | Yes | No | 0.1 | The Book of Mormon’s characterization of racial issues does in some ways appear to mirror racial issues in nineteenth-century America, though this kind of racism would not have been unusual in the ancient world. |

| 17 | Modern | Church government | Yes | No | No | 0.5 | The ordination of priests and apostles in the Book of Mormon exists, but doesn’t appear to align coherently with Protestant ideas in any detailed way, and it was obviously present to some extent in early Christianity. Specific, but not detailed or unusual. |

| 18 | Modern | Religious experience | Yes | No | No | 0.5 | Pentecostal experiences are described in a limited fashion in the Book of Mormon, but are not out of place in an early Christian or even a Hebraic context. Specific, but not detailed or unusual. |

| 19 | Modern | Democracy | No | No | No | 1 | Bushman makes a strong argument that both Nephite and American democratic forms are quite specific and the details don’t match. This one doesn’t count as having a shared theme. |

| 20 | Modern | Republican governmental forms | No | No | No | 1 | Bushman makes a strong argument that both Nephite and American forms of republican representation are quite specific and the details don’t match. This one doesn’t count as having a shared theme. |

| 21 | Modern | Free-masonry | No | No | No | 1 | As described by Greg Smith, the label of "secret combinations" was used for a lot more even in the nineteenth century than as a label for masonry. The details of secret combinations are provided in the Book of Mormon, and they are a much better match for how ancient robber-bands operated than for masonry. This one doesn’t count as having a shared theme. |

| 22 | Modern | American revolution | No | No | No | 1 | As Bushman describes, there is no actual description of the violent overthrow of an established monarchy in the Book of Mormon, and the Book of Mormon is absent the heroic narratives that characterized American literature. This one doesn’t count as having a shared theme. |

| 23 | Modern | Repentance and penance | No | No | No | 1 | Repentance has been a common theme in all ages of biblical and pre-biblical thought, and the details provided don’t match a Protestant or Catholic conception of repentance (e.g., the need for private confession). This theme is too pervasive in religious thought to count as a parallel. |

| 24 | Modern | Tran-substantiation | No | No | No | 1 | This theme doesn’t actually exist in the Book of Mormon. Alexander Campbell was smoking something particularly strong when he posited this one. |

| 25 | Modern | Fasting | No | No | No | 1 | Fasting has been a common biblical and pre-biblical religious practice and isn’t at all out of place in the Book of Mormon. |

| 26 | Ancient | Sacred south and profane north | No | No | No | 1 | Ostler maintains that the identification of Desolation in the North and Bountiful in the South correspond with ancient themes of a "profane north" and a "sacred south". I’m going to have to call this one a coincidence. |

| 27 | Ancient | Covenantal formulary | Yes | Yes | No | 10 | The sermon of King Benjamin follows a specific ancient literary structure called a covenantal formulary, and uses a form appropriate for a Judaism stemming from Lehi’s day. However, since this form is present in the book of Deuteronomy and the subject of covenantal renewal (though not the structure itself) was a common topic for Lutheran and Calvinist sermons, we’ll count it as specific and detailed, but not unusual. |

| 28 | Ancient | Prophetic lawsuits | Yes | Yes | No | 10 | The structure of the Lamanite prophet Samuel’s rebuke of the Nephites includes detailed elements of a "prophetic lawsuit" as engaged in biblical prophets. Though these lawsuits are present throughout the old and new testaments, their underlying structure would not have been well understood in Joseph’s day. Nevertheless, we count it as specific and detailed, but not unusual. |

| 29 | Ancient | Cosmic worldview | Yes | Yes | No | 10 | The Book of Mormon generally follows a cosmic worldview, with the elements seen as obeying God’s commands, generally more so than do humans. As this was a biblical worldview, and one expounded on greatly in Joseph’s day, we count it as specific and detailed, but not unusual. |

| 30 | Ancient | Jacob’s rent garment | Yes | No | Yes | 10 | The idea that there was a remnant of the patriarch Joseph’s garment (i.e., the coat of many colors), and that it held special religious significance, can be traced to ancient sources, and have no parallel in Joseph Smith’s day. There are quibbles about whether the specific details of those traditions match the Book of Mormon, however, and to reflect that we count it as specific and unusual, but not detailed. |

| 31 | Ancient | Messiah ben Joseph | Yes | Yes | No | 10 | The Book of Mormon references an echo of ancient Rabinnic traditions regarding a Messiah who would come through the line of Joseph, who would restore temple traditions, would be associated with the return of Elijah, and would be killed in combat with the enemies of God. That these traditions would also show remarkable parallels to Joseph Smith’s own life is startling. But given evidence that "Messiah ben Joseph" was known and discussed in Christian sources in Joseph’s day, we’ll count this as specific and detailed, but not unusual. |

| 32 | Ancient | Prophetic commissions | Yes | Yes | No | 10 | Lehi’s call as a prophet in 1 Nephi 1 takes the form of an anciently-derived prophetic commission and includes a throne theophany. As these structures are biblical and were starting to receive critical attention in Joseph’s day, we’ll count this as specific and detailed, but not unusual. |

| 33 | Ancient | Subscriptio | Yes | Yes | No | 10 | Joseph Smith stated that the title page of the Book of Mormon came from the last leaf of the gold plates, corresponding with the ancient practice of subcriptio, common in Greek and Mesopotamia literature. Specific, detailed, though not unusual. |

| 34 | Ancient | Tree of Life | Yes | Yes | Yes | 50 | Though critics would look to the dream of Joseph Smith Sr. as the primary source for Lehi’s dream, there are many more details in it corroborated by ancient texts and symbolism than are recounted by Joseph’s father, including similarities to the Narrative of Zosimus, Nephi’s connecting of the tree to the divine feminine, and the inclusion of the river of filthy water, which was a common ancient symbol for hell. Specific, detailed, and unusual. |

| 35 | Ancient | Pre-exilic wisdom traditions | Yes | Yes | Yes | 50 | As detailed by Margaret Barker, there are a number of details in the Book of Mormon that point to a pre-exilic theology and practices, particularly references to the pre-reform wisdom tradition. These elements would not have been well understood or commonly discussed in Joseph’s day or within his religious milieu. Specific, detailed, and unusual. |

| 36 | Ancient | Apocalyptic structure | Yes | Yes | Yes | 50 | 1 Nephi 11-14 follows the same pattern as examples of ancient apocalyptic literature, and in ways separate from biblical examples of apocalyptic styles. Specific, detailed, and unusual. |

| 37 | Ancient | Setting hearts on riches | Yes | Yes | Yes | 50 | The idea of treasures becoming slippery or disappearing, as described in the Book of Mormon, has strong parallels to the ancient Near East, such as with the Egyptian Instruction of Amenemope and in the Book of Enoch. These parallels go beyond similar thoughts posed in Proverbs, and are much stronger than money-digging parallels proposed from the early nineteenth century. Specific, detailed, and unusual. |

| 38 | Ancient | Olive tree allegory | Yes | Yes | Yes | 50 | The use of the olive tree as a metaphor for Israel is authentically ancient, and the details of olive horticulture are remarkable coming a New England farm boy. Specific, detailed, and unusual. |

| 39 | Ancient | Israelite law | Yes | Yes | Yes | 50 | There are numerous examples of details in the Book of Mormon matching the particulars of Israelite legal practice. Though many of these details are biblical, some are extrabiblical (e.g., the felling of trees on which someone had been hanged). Specific, detailed, and unusual. |

The best part about this series is just being able to see arguments and claims of the Book of Mormon laid out in an organized fashion.

Thanks!

I know I’m a little late to this, but I wanted to comment on number 4. That Christ would atone for our sins. I would point to Exodus 13:15. It says that “13:15 And it came to pass, when Pharaoh would hardly let us go, that the LORD slew all the firstborn in the land of Egypt, both the firstborn of man, and the firstborn of beast: therefore I sacrifice to the LORD all that openeth the matrix, being males; but all the firstborn of my children I redeem.” The firstborn men in Israel would NOT be sacrificed, but would be substituted (redeemed) by a lamb. Just like Isaac was redeemed by an angel and a goat. But the purpose of the Isaac story, the firstborn in Egypt and the redemption of the firstborn in Israel by a lamb is that the pre-exilic people were VERY familiar with the idea of a firstborn son being sacrificed for the sins of the family. Also Micah, a pre-exilic prophet, stated, “shall I give my firstborn for my transgression, the fruit of my body for the sin of my soul?” Micah 6:7.

Now… would they consider the idea that God himself would do that… I’m not sure.

I am fascinated by the hypothesis that Judah’s religion was different from northern israel’s and that those differences were not always in favor of Judah. Some of the things that Judah forgot, or repressed, may have been the idea of a suffering messiah that maybe the post-exilic jews re-discovered in Babylon or after they returned to Jerusalem after exile.

Hi Kyler,

You said, “Sounds like quite a bit of hedging for a book that’s about confidently answering the big questions of life and reality. Who says that spiritual influence would be within the domain of quantum field theory? It’s certainly not self-evident, despite your and Carroll’s apparent insistence otherwise.”

I apologize for not communicating more clearly. I didn’t mean to imply that this was self-evident. I meant to imply that it is the result of a detailed, intricate argument that takes a couple dozen chapters of his book to flesh out and is based upon the nuances of theoretical and experimental physics. He doesn’t claim that we know everything. He merely claims that we know some things. And the fascinating thing about it is we know a little more than you think we do.

If you are interested in understanding his actual arguments, I’d suggest you read the book. But if you don’t want your preconceptions on these matters challenged, I suggest you don’t.

Best,

Billy

October 31, 2021

Hi Billy:

This physics/matter/spirit horse is probably pretty much dead, but I am going to flog it around the track just once more, and then you can have as many last words as you want.

To keep from dying of boredom while I exercise to try to keep from dying (too soon), I watch lectures from The Great Courses: physics, chemistry, geology, astronomy, archaeology, religion, meteorology, history. Just trying to fill in the gaping gaps in my education.

Years ago, I watched a set of lectures on Dark Matter/Dark Energy given by a much younger Dr. Sean Carroll. Among other things, Dr. Carroll said that about 95% of all the matter/energy (“dark matter/dark energy”) in the universe is made up of “something”…but we have no idea what that something is.

Earlier this year, I watched another set of lectures entitled “Understanding Gravity” by Dr. Benjamin Schumacher. Schumacher’s summary of the state of knowledge in physics is much more recent than was Carroll’s, but his conclusion about dark matter/dark energy is the same: Dark matter/dark energy makes up well over 90% of the total stuff in the universe…and we have no idea what it is.

I am not claiming that dark matter is spirit matter because I sure as heck don’t know that one way or the other. What I do know is that Carroll was talking way beyond scientific understanding when he claimed, and you parroted, that there is no such thing as soul/spirit because we don’t observe unknown particles in the experiments that have been done to date.

When physicists don’t know what 95% of the stuff in the universe actually is, Carroll’s statement is flatly contradicted by the evidence. So a little humility is called for. One of the chief characteristics of truly great scientists is humility. Newton had humility, Carroll does not.

Dr. Carroll is a gifted lecturer and summarizer of science, but he is by no means a leading physicist, not even close, as you strongly infer.

Dr. Carroll has won no major prizes in physics (see his Wikipedia link below). His Google Scholar h score is 56 with less than 27,000 citations. Compare Carroll with Dr. Frank Wilczek, a top-drawer endowed professor of physics at MIT with 92,000 citations and an h score of 129. Carroll is employed as a staff research scientist at Caltech…a respectable and honorable post, but not a top-drawer position. All of Carroll’s most cited publications are reviews. He has not made a single noteworthy intellectual advance in physics…not one.

Carroll’s opinion about no evidence for a “spirit particle” is a lot like Dr. Michael Coe offering his “learned opinion” that the Book of Mormon had nothing to do with ancient American Indian cultures…based on his single reading decades ago of the Book of Mormon. Dr. Coe just flat didn’t know, and wasn’t interested in knowing, enough about the Book of Mormon to make such a statement.

Carroll also doesn’t know nearly enough to make the claim he did. Apparently intellectual hubris and prejudice are not confined to anthropology (Dr. Coe) but physics also has a worthy representative of intellectual arrogance and overreach in Dr. Carroll.

A little history is relevant here. Michael Thompson (aka Lord Kelvin, 1824-1907), one of the great physicists of all time, opined in about 1870 that physics was pretty much wrapped up. Just fill in a few details of classical Newtonian mechanics and we were done. Then came quantum mechanics and special/general relativity that literally upended the world of physics. Ooops! Not wrapped up after all.

So the very last thing we should do is assume that today’s understanding of the physical world is complete, as both you and Dr. Carroll have done.

I say this not to trash Dr. Carroll but to correct your misrepresentation of him as an intellectual leader in physics. He is not. He is a popularizer of science, a critic of theism and a defender of naturalism…his religion, as it appears to be your religion also.

Even with all of our past interactions, I had not realized until recently that you, Billy, are also a thoroughgoing naturalist. Since naturalism is your organizing principle, your religion, it is no wonder that you are loathe to examine evidence that might overturn your religion.

Prove me wrong, show which of the 131 (soon to be published as 156) correspondences between the Book of Mormon and the world of ancient Mesoamerica are not correct, that I am claiming evidence that does not exist.

Best of luck with that,

Bruce

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sean_M._Carroll

Hi Bruce,

You said,

“What I do know is that Carroll was talking way beyond scientific understanding when he claimed, and you parroted, that there is no such thing as soul/spirit because we don’t observe unknown particles in the experiments that have been done to date.”

This reminds me of a conversation I had as a teenager. Another kid told me you can in fact travel faster than the speed of light. He explained, “of course you could travel faster than the speed of light. It’s obvious. All you need to do is get into a spaceship and turn on the thrusters. As long as the thrusters are on, the spaceship will accelerate. If you accelerate in the same direction long enough, you can eventually achieve any velocity and thereby can travel faster than the speed of light. I’m surprised Einstein didn’t understand this.” Just as my friend should have had some understanding of the Theory of Special Relativity before declaring Einstein was wrong, you ought to have some understanding effective quantum field theory before declaring that Carroll is wrong.

“Carroll also doesn’t know nearly enough to make the claim he did. Apparently intellectual hubris and prejudice are not confined to anthropology (Dr. Coe) but physics also has a worthy representative of intellectual arrogance and overreach in Dr. Carroll.”

A better example of intellectual hubris are people who declare that physicists are wrong without even bothering to understand the details of what they’re allegedly wrong about.

“A little history is relevant here. Michael Thompson (aka Lord Kelvin, 1824-1907), one of the great physicists of all time, opined in about 1870 that physics was pretty much wrapped up. Just fill in a few details of classical Newtonian mechanics and we were done. Then came quantum mechanics and special/general relativity that literally upended the world of physics. Ooops! Not wrapped up after all. So the very last thing we should do is assume that today’s understanding of the physical world is complete, as both you and Dr. Carroll have done.”

Did I mention you don’t understand Carroll’s point? I think I did. After describing the trash heap of history that is “populated by scientists claiming to know more than they really do,” Carroll says, “My claim is different. (That’s what everyone says, of course—but this time it really is.) I’m not claiming that we know everything, or anywhere close to it. I’m claiming that we know some things, and that those things are enough to rule out some other things—including bending spoons with the power of your mind. The reason we can say that with confidence relies heavily on the specific form that the laws of physics take. Modern physics not only tells us that certain things are true; it comes with a built-in way of delineating the limits of that knowledge—where our theories cease to be reliable.”

Carroll, Sean. The Big Picture: On the Origins of Life, Meaning, and the Universe Itself (p. 155).

If you want to address Carroll’s actual point, you need to explain why effective quantum field theory isn’t really reliable within the specific boundaries Carroll articulates.

Best,

Billy

p.s. if you haven’t seen them yet, two of my two favorite Great Courses are “Science in the Twentieth Century” by Steven Goldman, and “How the Earth Works” by Michael Wysession.

Hey Billy,

I’m at best an armchair physicist, but as I understand, quantum field theory does have at least significant problem. Although it does produce some great predictions the energy density of the quantum field is significantly lower than estimated. Something like 10^120 orders of magnitude. Just like dark matter/dark energy hold mysteries, so does quantum field theory. I think Bruce’s point still holds.

Thanks!

Hi Carter,

The cosmological constant problem doesn’t have anything to do with effective quantum field theory, what it implies, and the strength of the evidence supporting it.

Dr. Carroll doesn’t claim that we know everything about everything. He merely claims we know some things, and that we know is enough to rule out some other things. It is a detailed, nuanced argument that is rooted in both theory and experimental evidence and continues to be rock solid.

If you don’t have a copy of Big Picture handy, the following link does a good job of explaining the point.

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2101.07884.pdf

Best,

Billy

“What you’ve essentially put together here is one big fat argument from silence. And one that in no way engages my comments here.”

The way you conceive of spirits and the arguments you’ve posited here are precisely what Dr. Carroll refutes in his book. I see little need to engage with your comments because they are made in complete ignorance of what effective quantum field theory implies about the plausibility of spirits and spirit forces.

You seem to imagine that Dr. Carroll’s argument is of the form “we haven’t seen spirits, therefore they must not be there.” That is why you call it an argument from silence, right?

His argument is much more sophisticated and specific than that. If you’ll bear with yet another quote, he says, “Consider a new particle X that you might suspect leads to subtle but important physical effects in the everyday world, whether it’s the ability to bend spoons with your mind or consciousness itself. That means that the X particle must interact with ordinary particles like quarks and electrons, either directly or indirectly. If it didn’t, there would be no way for it to have any effect on the world we directly see.” (page 181).

Can you see how “particle X” in this quote captures your conception of “spirit matter” that is more “fine and pure” than normal matter, yet is somehow capable of influencing the electrical impulses in our brains? If we know that “spirit matter” has the property of being able to subtly nudge electrical impulses in our brain, then according to quantum field theory, we know precisely how and where to look to find spirit matter. Specifically, we know that if we crash an electron into a positron in a particle accelerator, it will create a particle of spirit matter and a particle of anti-spirit matter. And if spirit matter is strong enough to have even a subtle influence on the brain, we know how hard we need the crash between the electron and positron to be in order to create the spirt particle and anti-spirit particle. And since spirit particles are things that by definition can influence electrical impulses in the brain, we know how to detect them in these experiments.

In the words of Dr. Carroll, “From 1989 to 2000, a particle accelerator called the Large Electron-Positron Collider (predecessor of today’s Large Hadron Collider) operated underground outside Geneva. Within its experiments, electrons and positrons collided at enormous energies, and physicists kept extremely careful track of everything that came out. They were hoping with all their hearts to find new particles; discovering new particles, especially unexpected ones, is what keeps particle physics exciting. But they didn’t see any. Just the known particles of the Core Theory, produced in great numbers.

“The same has been done for protons smashing into antiprotons, and various other combinations. The verdict is unambiguous: we’ve found all of the particles that our best current technology enables us to find. Crossing symmetry assures us that, if there were any particles lurking around us that interact with ordinary matter strongly enough to make a difference to the behavior of everyday stuff, those particles should have easily been produced in experiments. But there’s nothing there.” (page 182-183)

Two points. First, note that creating and destroying matter is what they do in particle accelerators; these experiments illustrate how 19th-century the concept of “matter can’t be created or destroyed” actually is. Second, the strongest, most robust, most proven theories of science tell us exactly how and where to find “spirit matter,” and after closely looking, it wasn’t there. Maybe quantum field theory is wrong and there really are spirits, but to date, the overwhelming scientific evidence is that “fine and pure matter” with the property of being able to somehow interact with our brains does not exist.

That’s why the ball is now in your court. How could quantum field theory be modified in order to accommodate the existence of spirit matter than can somehow interface with the physical bodies of living things, yet remain invisible in particle accelerators? A philosophical argument about whether a character in a video game can detect the person controlling it dodges the scientific argument.

Well, since the ball’s in my court I might as well give it another loft.

“A philosophical argument about whether a character in a video game can detect the person controlling it dodges the scientific argument.”

It’s not dodging the argument, it’s answering it. The thought experiment exposes the small-mindedness of Carroll’s entire proposition. He’s a sophisticated handyman with a big hammer who not only sees a world full of nails, he insists nails are the only things that could ever exist. He (and you) can’t imagine a reality that exists and moves outside of quantum field theory, or substances that don’t involve particles discoverable via collider. Thereby the naturalistic worldview remains perfectly safe in the cold dark of its cave, having defined out of existence anything that lies outside its methodological purview.

You lightly set aside the philosophical argument, but the philosophy is exactly what Carroll should’ve been paying more attention to. Even his sympathetic reviewers acknowledge the awkwardness he displays in handling the philophical nuance of these questions (along with the triteness of his associated moral reasoning). You keep pressing forward confidently in expounding the physics–and demanding answers on physics’ own terms–when the physics itself is missing the heart of the problem. Perhaps you should consider spending a little more time working through the philosophical framework of these positions. In the meantime, I’ll render unto Physics the things that belong to it, and unto philosophy, theology, and logic the things that lie under their sway.

From a philosophical perspective you can argue that anything is possible. You can argue that spirits exist. That people can bend spoons with their minds. That we could solve the world’s energy problems with perpetual motion machines. That the earth was created 6,000 years ago and the devil created the dinosaur bones to deceive us. Whatever.

What seems more fruitful is to begin with a strong understanding of what science actually says about the nature of reality, and how confident science is about the specific conclusions in question. Just because you can visualize a world where spaceships can travel faster than the speed of light, or a world where effective quantum field theory has no bearing on how “fine and pure” spiritual particles interface with the human brain, or a world that was created by God 6,000 years ago ex nihilo, doesn’t necessarily mean you are more open minded than I am. It might just mean you are naiver about the current state of scientific knowledge.

Just in from the LHC. Famous last words indeed.

https://scitechdaily-com.cdn.ampproject.org/v/s/scitechdaily.com/new-fundamental-physics-unexplainable-phenomena-from-large-hadron-collider-experiment/amp/?amp_gsa=1&_js_v=a6&usqp=mq331AQIKAGwASCAAgM%3D#amp_tf=From%20%251%24s&aoh=16356145792637&csi=0&referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com&share=https%3A%2F%2Fscitechdaily.com%2Fnew-fundamental-physics-unexplainable-phenomena-from-large-hadron-collider-experiment%2F

Also note the reference to requiring 5 sigma prior to seeing the result as a genuine discovery.

Is this an example of “famous last words,” or is it an example of “I don’t understand the argument of the world class physicist I’m criticizing because I haven’t bothered to read his book”?

Carroll’s arguments are about effective quantum field theory within its domain of applicability. He never claimed we had discovered all particles and forces. Nor did he claim that the standard model would hold for infinitely small distances or time intervals. Nor did he claim it would hold for infinitely high energy levels. His claim is that whatever is left undiscovered won’t be strong enough or or travel across distances long enough to have any effect on everyday reality, including the working of the human brain.

This quote is relevant:

“The most likely scenario for future progress is that the Core Theory continues to serve as an extremely good model in its domain of applicability while we push forward to understand the world better at the levels above, below, and to the side. We used to think that atoms consisted of a nucleus and some electrons orbiting around it; now we know that the nucleus is made of protons and neutrons, which are in turn made of quarks and gluons. But we didn’t stop believing in nuclei when we learned about protons and neutrons, and we didn’t stop believing in protons and neutrons when we learned about quarks and gluons. Likewise, even after another hundred or thousand years of scientific progress, we will still believe in the Core Theory, with its fields and their interactions. Hopefully by then we’ll be in possession of an even deeper level of understanding, but the Core Theory will never go away. That’s the power of effective theories.”

Carroll, Sean. The Big Picture: On the Origins of Life, Meaning, and the Universe Itself (p. 193).

“Carroll’s arguments are about effective quantum field theory within its domain of applicability.”

Sounds like quite a bit of hedging for a book that’s about confidently answering the big questions of life and reality. Who says that spiritual influence would be within the domain of quantum field theory? It’s certainly not self-evident, despite your and Carroll’s apparent insistence otherwise.

“His claim is that whatever is left undiscovered won’t be strong enough or or travel across distances long enough to have any effect on everyday reality, including the working of the human brain.”

How do we know that they won’t if we haven’t discovered them yet? Because the equations seem to work? Well, if this particular result turns out, that would mean the equations aren’t working as expected, thus all the talk about having to rework the Standard Model itself. Like it or not, a result like this one (or, if this one doesn’t pan out, the next inevitable discovery) directly undermine’s Carroll’s confidence that he’s got it figured out enough to completely rule out some sort of physical medium for spiritual influence.

Nevermind that one of the defining features of that physical medium would probably be that it doesn’t interact with normal matter under ordinary conditions (e.g., the metaphor generally relies on “spiritual eyes”, not “spiritual fingers”–it’s something to be perceived not touched).

Nevermind that such external influence wouldn’t actually need a physical medium, a la the virtual world example.

“we didn’t stop believing in protons and neutrons when we learned about quarks and gluons. Likewise, even after another hundred or thousand years of scientific progress, we will still believe in the Core Theory, with its fields and their interactions.”

This feels like a false equivalency to me. Yes, we still believe in atoms and protons and neutrons. But when it comes to fields and interactions, discovering the layer beneath irrevocably altered the layer above it. Quantum mechanics rendered Newtonian physics obsolete. It’s still “useful” and “effective” to use Carroll’s parlance, but it’s not the way reality works. There’s a level where it simply breaks down. And though we generally don’t need quantum mechanics to describe how things work on the macro level, that’s not to say that quantum effects couldn’t possibly have bearing on what happens above it (quantum computing would be a good example here).

Could a more accurate understanding of physics, a physics somewhere “above, below, or to the side”, lead us to see quantum field theory as simply inadequate to describe life at that level? Could that level include spiritual influence? Maybe–though I’m not about to hold my breath that it’ll happen in my lifetime.

From what I can tell, Carroll is careful to admit as much in his book, but both he and you try to have it both ways. You admit nuance and limitation and the possibility of new discovery, but at the same time insist that you know enough to be confident in your conclusions. When it comes to questions as large as the ones Carroll’s trying to chew on, I’m afraid the laws of logic require that his cake be consumed once it makes its way down his throat.

October 28, 2021

Hi Billy,

In your recent comments, you make at least two errors of logic (reasoning) and one error of fact that need to be pointed out.

First logical fallacy: you cannot assume that because Joseph might have known about the conservation of mass from the chemical experiments of Lavoisier he actually did know about Lavoisier’s work. You just wave your hands. You infer that Joseph could have learned about Lavoisier at the University of Nauvoo. But you don’t show that Lavoisier’s book was used at the University of Nauvoo, or that Joseph ever studied at that University, and if he studied there, that he could even have learned about conservation of mass from Lavoisier’s book.

First factual error: you don’t show that Lavoisier’s book taught the conservation of mass. In fact, you cannot show it for a very good reason: that book is primarily a book of scientific methods to be employed in careful chemical research. It does not clearly state nor summarize the conservation of mass as a general principle. Lavoisier’s work on oxidation reactions did lay a foundation for later work in chemistry that eventually demonstrated that mass is conserved in ordinary chemical reactions.