Intro/FAQ ⎜ Episode 1 ⎜ Episode 2 ⎜ Episode 3 ⎜ Episode 4 ⎜ Episode 5 ⎜ Episode 6 ⎜ Episode 7 ⎜ Episode 8 ⎜ Episode 9 ⎜ Episode 10 ⎜ Episode 11 ⎜ Episode 12 ⎜ Episode 13 ⎜ Episode 14 ⎜ Episode 15 ⎜ Episode 16 ⎜ Episode 17 ⎜ Episode 18 ⎜ Episode 19 ⎜ Episode 20 ⎜ Episode 21 ⎜ Episode 22 ⎜ Episode 23

[Editor’s Note: This is the eleventh in a series of 23 essays summarizing and evaluating Book of Mormon-related evidence from a Bayesian statistical perspective. See the FAQ at the end of the introductory episode for details on methodology.]

[Author’s Note: This essay was written prior to Paul Fields’ presentation at the 2021 FAIR Conference, and does not incorporate any of the new evidence he discussed.]

The TLDR

It seems unlikely that someone could fake stylometric evidence for multiple authors within the Book of Mormon text.

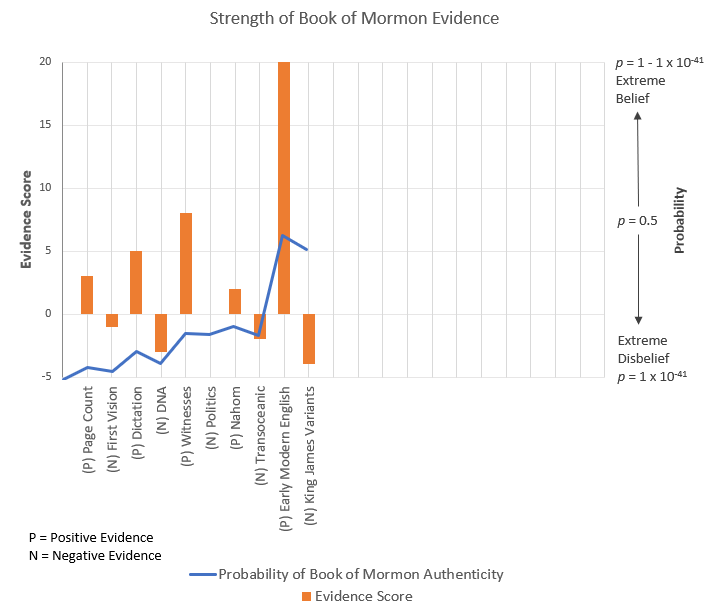

Stylometric evidence regarding the Book of Mormon has been around for almost four decades now. It made a bit of a splash back in the 80s, but it seems to be plagued by dismissal from critics and ambivalence from the faithful. After taking a hard look at the evidence, though, it’s clear that it strongly favors Book of Mormon authenticity. If we assume that Joseph or his scribes didn’t have the skill to change subtle word patterns while dictating, the probability of single authorship is extremely low (1.3X x 10-14). Even if Joseph had literary skill along the lines of Twain and Dickens, the probability that a single author composed the text is p = .00002. This evidence substantially damages the idea that Joseph or any other nineteenth-century author is responsible for the Book of Mormon.

Evidence Score = 5 (the probability of an authentic Book of Mormon increased by five orders of magnitude)

The Narrative

When we last left you, our ardent skeptic, you’d been somewhat emboldened by your discovery of unexpected King James language within the book you’d been reading, a book which was decidedly not the Bible. You feel a fresh sense of vigor as you continue your way through the book, page by page, convinced that further evidence of fraud would be around the corner. You’re almost saddened when you read about the inevitable fracture of the book’s doomed family, touched by the earnest love of the family’s patriarch, who, on his deathbed, begs his wayward sons to turn again to the God that had borne them so far from their former home. You’re only slightly perturbed by the tedium of yet further chapters lifted almost straight from Isaiah, but are still paying enough attention to feel the pathos of the book’s protagonist as he laments his own weakness, throwing his soul on the mercy of his Savior. Your prior, devout self would have been truly inspired by the vulnerability and humility on display in the final sermon of this Nephi, but you can no longer find much room for such base sentimentality.

You’re somewhat surprised to have come to the end of Nephi’s story so quickly, with still hundreds of pages left in the book. It seems a bit odd to abandon a protagonist so quickly after having developed him so thoroughly. Nevertheless you press on, finding that the prophet/hero soon turns the narrative over to his little brother, who goes by the name of Jacob.

It’s there that you stop and think about what just occurred. You now have an entirely different narrator for the story, and at this rate there is likely to be many more. You wonder at the narrative feat on display in such a transition, and wonder at the foolishness of any who would attempt it. To pretend that the book now had a different author would require compositing a completely different voice for the prose, something quite difficult for even the best of authors. Smith might be able to fool some people now, but you think of what sorts of detailed analysis might be possible in the future, and what the results of those analysis would say about the authorship of the book.

If the book was the product of a singular mind and a singular voice, surely such analyses would be able to tie the book straight to the mind of that backwoods farm boy, or to someone close to him. On the other hand, if the results suggested otherwise—well, that would definitely be difficult to explain. It seems to you that it would be unlikely that anyone could successfully fake the presence of multiple authors in a text.

The Introduction

It’s fairly common for critics of the Book of Mormon to ignore potential positive evidence for the book’s authenticity, but there are few types of evidence avoided so thoroughly as stylometry—computational analyses analyzing the word patterns present in the text. Studies have analyzed such patterns in the Book of Mormon and compared them with those used by the alleged authors of the text, people like Joseph Smith, Oliver Cowdery, and Sidney Rigdon. They can also compare those patterns internally, which can help provide a sense of how likely it is that the book was produced by a single author, and whether the book’s internal authorship structure matches with the structure suggested by the analysis.

These analyses have been around since the 80s, and much of the conversation surrounding them appears to have played out. Critics feel very comfortable dismissing them out of hand (which is perhaps predictable), and even the faithful seem to have their doubts about the method or the strength of the evidence. But with these stylometric studies we have an ideal piece of evidence for which we can apply Bayesian analysis—a consistent, quantitative method for which we can form clear expectations and that have transparent, well-understood results. Let’s get cracking.

The Analysis

The Evidence

We’re going to have to get in the weeds a bit when it comes to the stylometric evidence, so bear with me. We’ll start by describing stylometric methods and then describe each of the major studies that have been conducted on the topic.

Stylometry. Sometimes referred to as wordprint analysis, stylometry is a quantitative method for comparing the writing styles found within various texts. The analysis generally consists of taking a body of words and conducting frequency counts of different kinds of words within each text. Though there are exceptions, most analyses focus on non-contextual words, or words that are connected with the structure of sentences and that should appear with similar frequency regardless of the type of content the text is discussing. For instance, if a person wrote two different texts, one on banking and one on Greek mythology, we would expect them to use different words to describe their content, but we wouldn’t necessarily expect them to use words like and, or, but, the, or it any differently within the two texts. If the pattern of those non-contextual words does differ between two different texts, we could rightly ask why that’s the case. And at least one explanation could be because the text has two different authors—authors who have different habits of using those non-contextual words.

Stylometry has been and is still used as a common method for assessing the authorship of various works. It’s been applied most often in the humanities to, say, assess the authorship of Shakespearean plays or Japanese poetry or Aristotelian essays or the Federalist Papers. But it’s also been used in forensic settings and by modern tech companies to assess and categorize comments in online message boards, among other things. As much as critics might claim otherwise, stylometry, on the whole, is a mainstream, respected method whose use or validity hasn’t dimmed over time.

There are, of course, limitations and valid criticisms to apply to stylometry. The statistical tests applied within stylometry can report whether a difference between two tests exists and isn’t due to chance, but it can’t tell you why that difference exists. There are lots of potential ways that differences in non-contextual word frequency could come about. Differences could be produced by the text having different editors, being produced at different points in time, being a different genre (e.g., poetry vs. prose, or historical description vs. religious sermon), creating different character “voices,” or having been translated by different people. There’s also a number of analytic choices that could affect or obscure the outcome, such as by which texts are included or, in the case of the Book of Mormon, how the text is divided and assigned to its presumed authors.

These potential sources of variability mean that we should exercise some caution when interpreting the results of stylometric analysis. It doesn’t, however, mean that such analyses are inherently useless. It also means that not all analyses are created equal, so we’ll have to think through the results of each of the different studies carefully to give us a sense of how worthwhile they might be.

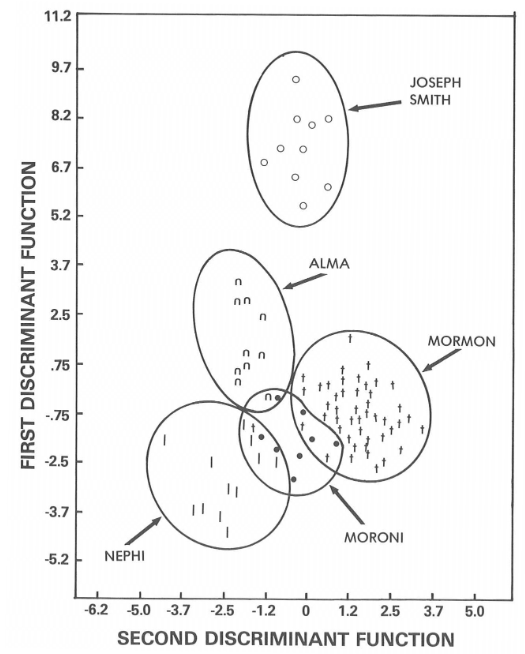

Study results. There are six main stylometric studies that are generally referenced when it comes to assessing the authorship of the Book of Mormon. The first was a study conducted at BYU by Wayne Larsen and Alvin Rencher in 1980. This study used three statistical analyses comparing non-contextual word patterns for as many as 38 different words used by the presumed authors within the Book of Mormon as well by potential nineteenth-century candidates (Smith, Rigdon, Spaulding, Pratt, Phelps, and Cowdery). The first analysis was a set of MANOVAs (multivariate analyses of variance), which compared the variability of word frequencies within each author to variability between them. The second was a cluster analysis that statistically grouped blocks of text into categories based on word patterns. The third was a discriminant analysis, which attempts to describe statistically how authors differ from each other and measures how closely they match. All of the analyses suggested strong differences in the patterns of words used by the various authors of the Book of Mormon, and that those patterns were a poor fit for nineteenth-century authors, including Joseph. Furthermore, the patterns within the primary Book of Mormon authors were very similar to each other and clearly distinguishable from the others, as you can see in the figure below:

Larsen’s study drew a great deal of controversy, inside the Church as well as without. The finding was initially treated with a great deal of excitement, with a university forum on the topic at BYU, as well as a number of articles in the Church News. But the study found a lot of early opposition as well, with a thoughtful critique published in Sunstone, as well as a response by Larsen, who acknowledged many of the original study’s shortcomings, but also offered robust responses to each of the critiques.

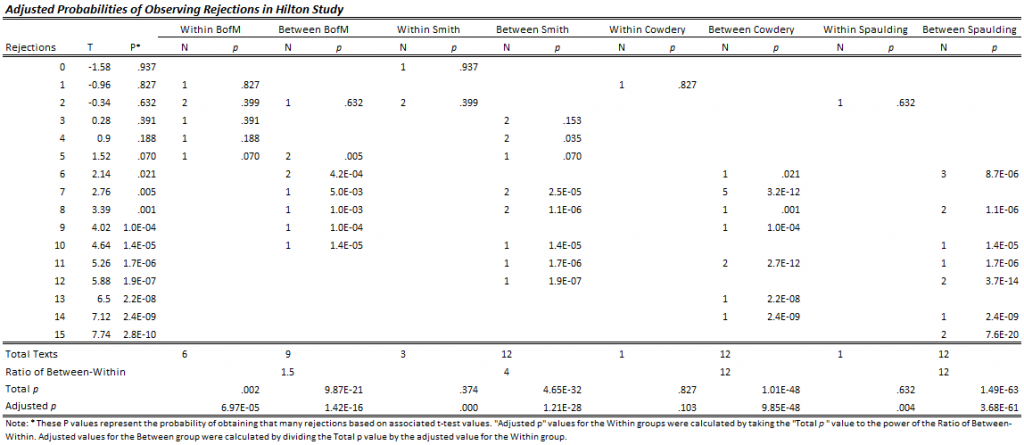

This led a few years later to the second study, conducted by John Hilton, working at Berkeley with a multidisciplinary team of independent scholars who, importantly, were not members of the Church. This study, first published in 1987, included substantial improvements over the previous study, such as by 1) using 65 word-pattern ratios alongside non-contextual word patterns, 2) using better statistical tests (Mann-Whitney Non-Parametric tests) with more workable assumptions than those associated with MANOVA, 3) developing an improved word-group counting method, 4) comparing only two texts at a time rather than all the texts together, 5) using the earliest available Book of Mormon manuscripts, and 6) verifying the sensitivity of the analysis with an improved set of control texts of undisputed authorship. When it came to testing the internal patterns of the Book of Mormon, they conservatively restricted the comparisons to word-blocks that were the same genre and excluded the phrase “and it came to pass.”

Their method involved conducting a set of tests comparing sets of two 5,000-word blocks on the word frequency patterns and word-pattern ratios, counting the number of times that the null-hypothesis (that the texts were written by the same author) was rejected. For works of known authorship, they plotted the number of rejections for texts from the same author and found that they were normally distributed with about the number of rejections you would expect due to chance given the number of tests they conducted (M = 2.58, SD = 1.6), while those authored by different people had a much higher average number of rejections (approximately 7). If two texts received more than 7 rejections when compared, it would be a good indication that the texts were not written by the same author. Since each set of tests is relatively independent, you can even calculate the overall probability that the texts are authored by the same people. Overall, their results provided solid support for the conclusions of the Larsen & Rencher study—texts within the Book of Mormon purported to be written by the same author received few rejections, while those purported to be written by different authors received many, and the Book of Mormon texts were all poor matches when compared with nineteenth-century authors.

A third study was conducted by David Holmes, using what he termed “vocabulary richness”—identifying words that were used once, twice, three times, etc., and comparing the Book of Mormon, the D&C, the Book of Abraham, and Joseph Smith’s writings. He concluded from his analysis that Joseph was unlikely to be the author of the Book of Mormon, but that writings from Nephi, Mormon, and Alma all had similar vocabulary, and thus were likely to be a single author. Unfortunately for Holmes, the accuracy of his method was later demonstrated to be lacking—for works of undisputed authorship, vocabulary richness only correctly classified 23% of the works, compared to 96% and 92% for word patterns and word-pattern ratios, respectively.

It would be a few years before another competing study would be published, this one by Matthew Jockers and his colleagues at Stanford. This fourth study was a step forward in some ways and a step backward in others. It applied a statistical method called Nearest Shrunken Centroids (or NSC), a method borrowed from genetic research which can be used to compare items on hundreds or even thousands of different characteristics. The method calculates the statistical center (or “centroid”) of that set of variables, and shows those items whose centers are closest to each other. Jockers worked to apply this method to the problem of Book of Mormon authorship, seeing how closely the Book of Mormon related to a number of authors.

There was, however, one small problem: The NSC method requires what’s referred to as a “closed set”—the analysis could only compare the Book of Mormon to the authors they happened to choose, picking whatever author among that set happened to be the closest match. Since they didn’t have any other material on hand that happened to have been written by Mormon or Nephi or Alma, outside the Book of Mormon itself, that meant that all Jockers had to choose from were those from the nineteenth century—Joseph Smith, Sidney Rigdon, Oliver Cowdery, Solomon Spaulding, and Parley P. Pratt. The study concluded that since Rigdon and Spaulding are the closest matches to much of the material in the Book of Mormon out of that set, that therefore those two likely collaborated as authors of the book.

Hopefully the problem here is an obvious one. Asking which nineteenth-century author is closest to the Book of Mormon is akin to asking which American city is closest to the Nile—you’ll get an answer, but it won’t be a meaningful one. “Closest” doesn’t necessarily imply “close.”

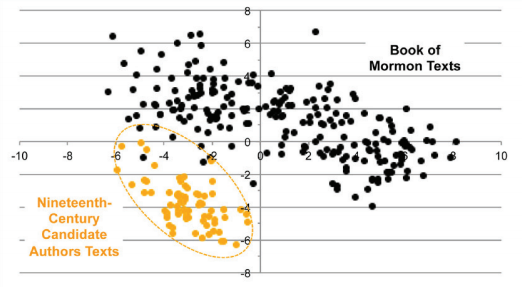

Recognizing the limitations of the methods used by Jockers, Paul Fields and his colleagues at BYU conducted a fifth study. They begin by thoroughly demonstrating the absurdity of treating Book of Mormon authorship as a closed-set problem. For instance, applying Jockers’ method to other potential texts, they found that it pegs Rigdon as the probable author of 34 of the Federalist Papers and about 30% of the Bible. They use similarly absurd analogues of Jockers’ method to show that prominent nineteenth-century anti-LDS author Tyler Parsons wrote 65% of the Book of Mormon, and that Oliver Cowdery was the probable author of Jockers’ own paper! They make it very clear that the Jockers study is worth about as much as the paper it was written on.

Fields and his colleagues go on to describe their own adaptation of the NSC method, which they term Extended Nearest Shrunken Centroid (ENSC) analysis. This method is “open-set,” in that it allows for the possibility that some other unknown author is responsible for the text. They did this by using a statistical procedure to simulate that unknown author, which was given features that were minimally similar to the Book of Mormon—essentially, a (minimally low) bar that a proposed author would need to clear for them to be seriously considered as the author of the Book of Mormon. They performed a variety of different tests using this analysis, all pointing to the same conclusion. Very few of the non-Isaiah chapters were assigned to nineteenth-century authors, with most assigned to an unknown author. Those that were assigned to Rigdon or Spaulding (about 9% of chapters), were distributed randomly through the text, suggesting that those assignments were due to chance.

This figure from the Fields paper sums up the evidence as well as anyone could:

There’s also an additional study from Fields, Bassist, and Roper comparing the diversity of styles within the Book of Mormon to the diversity within fictional works by nineteenth-century novelists. That study also strongly supports the conclusion that the Book of Mormon has multiple authors, as the Book of Mormon has more stylistic variety than the four authors they test combined.

Lastly, I’ll give mention to some amateur work done by an anonymous author that purports to show that the wordprint patterns can be explained by separating out narratives, sermons, and a somewhat random mismish of others featured late in the Book of Mormon. Though I haven’t seen any professional commentary on this approach, a few things stand out: 1) the Hilton study specifically controlled for differences between narrative and sermon, and still found substantial differences, 2) the fact that the third group represents a somewhat miscellaneous category containing both sermon and narrative cuts pretty strongly against their primary argument, and 3) unless there are three different authors that could be reliably assigned to each section (including switching people out halfway through certain chapters), the staggering amount of variability of style within the Book of Mormon remains unexplained. The work is thoughtful and sincere, but ultimately weak, which I’d be happy to explain further if anyone’s interested. I don’t see any reason to incorporate this work any further into my analysis.

The Hypotheses

There are a couple of different ways these findings could have come about. These should be relatively straightforward, but there are a couple of niggles to think through as we lay them out.

The Book of Mormon was written by multiple ancient authors—This theory posits that the authorship of the Book of Mormon is as the text states it is, with multiple ancient authors all contributing to the text over a period of hundreds of years. Even with the text having undergone a translation process, we would expect the text to show signs of having been authored by multiple people, and we wouldn’t be surprised if the text failed to show signs of having been authored by Joseph, his scribes, or other purported nineteenth-century authors.

It’s important to note, though, that signs of single-authorship or of the text matching Joseph’s style would’ve been far from fatal to theories of Book of Mormon authenticity. Faithful scholars could’ve easily leaned on Joseph’s translation process to explain those results. But that’s not how it played out, and faithful scholars have nothing that would require an explanation.

The Book of Mormon was authored by Joseph, or some other modern individual connected with him, as a work of fiction—This theory would state that the Book of Mormon is a purely modern product, having originated as a fictional work. Notice that I’m allowing for someone other than Joseph to have authored the text, mostly because the studies explicitly explore that possibility. If the results of those studies definitively pinned authorship on Spaulding or Rigdon, then that would certainly have been a tough pill for the faithful to swallow.

It is, of course, also possible that some other unknown modern individual authored the Book of Mormon, and that’s a possibility that these studies can’t rule out. The trouble with that theory is it’s essentially unfalsifiable—there’s no way to test the writing styles of everyone that existed in the early nineteenth-century. It would also be hard to support such a theory, particularly in the absence of any other supporting evidence.

This theory also allows (and likely requires) the book’s modern author to be an exceptionally talented author with savant-level writing skills. The question, at that point, would be how expected or unusual it would be for someone to have those skills.

Prior Probabilities

PH—Consequent Probability of Ancient Authorship—Based on the evidence considered up to this point, our estimate for the probability that the Book of Mormon is ancient remains in decidedly skeptical territory, at p = 1.73 x 10-8. Here’s a look at where we’ve been thus far:

PA—Consequent Probability of Modern Authorship—The remaining probability can be assigned to the probability of modern authorship, at p = 1 – 1.73 x 10-8.

Consequent Probabilities

CH—Consequent Probability of Ancient Authorship—It’s hard to tell how likely we would be to observe distinguishable word patterns in the Book of Mormon text, if indeed different ancient authors were responsible for the text. There are certainly scenarios where we might not detect that difference, such as if the dictation or scribal process obscured those patterns in some way. But seeing those multiple patterns—and having them differ from those of proposed nineteenth-century authors—is certainly consistent with the Book of Mormon as authentic. I don’t see a problem assigning a consequent probability of p = 1 in this case.

CA—Consequent Probability of Modern Authorship—These studies are really useful in this regard, as handy p-value estimates are often attached to the results they present. The original Larsen study reported a probability of “1 in billions” that the Book of Mormon had a single author, given the significance of the MANOVA. The Hilton study used some of the more extreme tests comparing Nephi’s and Alma’s writings, which showed 7, 8, 9, and 10 rejections, to calculate a similar probability—each of those tests had a t-value attached, and since they represented separate sets of words, the tests could be assumed to be independent, meaning we could multiply the p-values for those tests together. The result was an estimate for single authorship at p = 1.3 x 10-14. It’s also possible to calculate similar estimates for how likely it was that the Book of Mormon texts matched the writings of Joseph Smith, Oliver Cowdery, and Solomon Spaulding, and the results were equally grim; the respective p-values were 2.7 x 10-20, 8.1 x 10-19, and 7.3 x 10-28.

Just for fun, I conducted my own calculations of those p-values using a somewhat different method. Instead of just counting tests with rejections higher than 6, I counted all the tests, comparing those conducted within each author with tests conducted between them and Book of Mormon authors (or between Nephi and Alma). Since there were more tests conducted between authors than within authors, I made an adjustment that accounted for that difference in each case (I took the within-author estimate and took it to the power of the ratio of the number of between-author texts to within-author texts; see the Appendix for a table with more details). The results are comparable, and not any more kind to the hypothesis of single or nineteenth-century authorship. You can see them in the table below:

| Comparison | Within Author(s) | Between Authors | Adjusted Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Authorship | 6.29 x 10-5 | 9.87 x 10-21 | 1.42 x 10-16 |

| Joseph Smith | .003 | 4.64 x 10-32 | 1.21 x 10-28 |

| Oliver Cowdery | .103 | 1.01 x 10-48 | 9.84 x 10-48 |

| Solomon Spaulding | .004 | 1.49 x 10-63 | 3.68 x 10-61 |

The first Fields study doesn’t provide for as clean a set of estimates, particularly for single authorship, but we can get a sense of how unlikely it is that the true author is in the set of authors identified by Jockers. Based on their controls, there was a false-negative rate of 11.9%, so we should expect Fields’ tests to provide false negatives for at least a similar proportion of the Book of Mormon chapters, or around 29 false negatives. Assuming we would get that many false negatives just for the “unknown author” category, the probability of getting 174 chapters assigned (using a Poisson distribution) would be p = 8.97 x 10-75. Also not great for our alternative hypothesis.

If we assumed that all these tests were independent, then we could even multiply some of these values together to get an even more prohibitive estimate of the probability of single or nineteenth-century authorship. But we can’t. All of the studies rely on the same word patterns when producing their estimates, and though it’s hard to say how independent word patterns would be from word-pattern ratios, it’s best to assume that they’re fully dependent. The question, then, is which study gives us the best estimate? If we were really nice to the critics, we would probably go with the Larsen study, but methodological quality has to count for something. The Hilton study is the superior study on every metric, and was conducted by an independent team of non-LDS researchers to boot.

There’s also the question of how we incorporate the two aspects of the critical hypothesis. As we’ve described it above, the Book of Mormon should need to be both singly-authored AND attached to an author from the early nineteenth century. If either of those aren’t true, then so is the hypothesis of a modern forgery. In reality, though, evidence of single OR nineteenth-century authorship would be pretty embarrassing to Book of Mormon authenticity. Because of that, it’s not completely fair to treat this as an AND problem, so we’ll treat it as an OR problem—which means that we should go with the highest available probability for those two possible options. That would leave us with Hilton’s estimate of the probability of single-authorship, or p = 1.3 x 10-14.

But, since I’m in a merciful mood, we’re not yet done with our analysis. That probability only applies if we take Hilton’s results at face value, and that the results they obtained couldn’t also be produced by other means than by differences between authors. Could a single author produce the kind of variability that we observe in the Book of Mormon, just in terms of their own creativity?

For instance, can an author change stylometric word patterns by imitating a different style (e.g., biblical)? The data don’t completely fail us in this regard. There have been cases where individuals have tried to replicate others style, such as when Marie Dobbs, herself a skilled writer, attempted to replicate the style of Jane Austen when attempting to complete a novel that Jane left unfinished after her death. Stylometric analysis was able to find clear differences in the patterns of the two authors.

But not all authors are created equal. One particular example is that of William Faulkner. Shortly after joining the BYU faculty, Hilton and his students conducted a study comparing the different narrators within Faulkner’s novel As I Lay Dying, wherein he used rather stark differences in speech patterns, dialects, and characterizations to show the different personalities and life circumstances of those narrators. Hilton compared those narrators using the same method as he had for his Book of Mormon study. The results were rather impressive. None of their control authors were able to provide much variability in their style, as measured by their analysis, but Faulkner’s narrators did show stark differences, as much variability, in fact, as did the Book of Mormon. It is, indeed, possible to fake differences in style for different characters.

Now, there are a bunch of reasons why it isn’t fair to compare the Book of Mormon to Faulkner, as detailed in this informative article on Rational Faiths. And, as someone with a couple novels under his belt, I don’t buy that the differences between Alma and Nephi can be attributed to different characterizations. If you can tell me on what basis Alma and Nephi could be given different dialects or characterized differently enough to appreciably change their patterns of speech, I will personally hand you a gold star. That type of change makes perfect sense for Faulkner’s narrators. It makes no sense in the context of the Book of Mormon.

That in mind, however, showing that it’s possible to alter word patterns so dramatically changes the nature of the question. The question isn’t, how likely is it that the patterns of Joseph’s writings match the patterns of the Book of Mormon? The question is, how likely is it that Joseph was a Faulkner?

And that’s where the Fields, Bassist and Roper study comes in. That study asks the right question, comparing the Book of Mormon not to Joseph’s other writings, but to other nineteenth-century novelists, asking how its word patterns stacks up against his purported peers. They found that people can indeed create different characters and narrators with appreciably different writing styles, but the sort of variety that we see in the Book of Mormon has to be exceptionally rare. Compared to the four authors they examined (Dickens, Twain, Austen, and Cooper), the Book of Mormon more than doubled the average variability, and was head and shoulders above even Dickens, the most variable among the authors.

Though the sample size of the authors is small, that study still gives us our best shot at producing the estimate we need for this part of the analysis. Using the mean (M = 1.48) and standard deviation (SD = .34) of the four nineteenth-century authors, we find that the Book of Mormon is 4.27 standard deviations from that mean, with an associated probability (via Z table) of observing a single author with as much variability as the Book of Mormon estimated at p = .00002. It’s by no means a guarantee that Joseph would have Faulkner-level skill in altering word patterns, even if we consider him among the greatest of nineteenth-century novelists.

Posterior Probability

PH = Prior Probability of the Hypothesis (the probability that the Book of Mormon is authentic, based on all the evidence considered thus far, or p = 1.73 x 10-8)

CH = Consequent Probability of the Hypothesis (the probability of observing the stylometric evidence we have, given the Book of Mormon’s claim of multiple ancient authors, or p = 1)

PA = Prior Probability of the Alternate Hypothesis (the probability that the Book of Mormon is not authentic, based on earlier evidence, p = 1 – 1.73 x 10-8)

CA = Consequent Probability of the Alternate Hypothesis (the probability of observing the available stylometric evidence if the Book of Mormon was authored by a single nineteenth-century individual, or p = .00002)

PostProb = Posterior Probability (our new estimate for the probability of an authentic Book of Mormon)

| PH = 1.73 x 10-8 | |

| PostProb = | PH * CH |

| (PH * CH) + (PA * CA) | |

| PostProb = | (1.73 x 10-8 * 1) |

| ((1.73 x 10-8) * 1) + ((1 – 1.73 x 10-8) * .00002) | |

| PostProb = | .000865 |

Lmag = Likelihood Magnitude (an estimate of the number of orders of magnitude that the probability will shift, due to the evidence)

Lmag = log10(CH/CA)

Lmag = log10(1/.00002)

Lmag = log10(50000)

Lmag = 5

Conclusion

Based on much of what we’ve covered here, you might think that stylometry might have been a critical strike in favor of the Book of Mormon, and it certainly had the potential to be. Absent the potentially freakish Faulkner, the evidence would be up to 10 orders of magnitude stronger than our analysis shows. Even then, the stylometric evidence is no slouch. It represents solid, replicable evidence that’s relatively free from subjectivity and bias. The words on the page are the words on the page. Anyone can go ahead and count them and see the same thing. What they add up to is a book Joseph is very unlikely to have authored, even if you allow that he was a literary genius, par excellence.

Skeptic’s Corner

There’s at least one thing that should immediately jump out to the critics—basing my probability estimate on a sample of four authors is obviously less than ideal. It’s entirely possible that looking at a much larger sample of authors could reveal a substantially greater variability in word patterns on average. That, of course, is a two-edged sword, as increasing the sample could, in all likelihood, lower that average, greatly strengthening the case of the stylometric evidence.

It would also be worth someone’s time to test how common it is for people to be able to consciously fake multiple authorship. This sort of study, which has been termed “adversarial stylometry,” has looked at people’s ability to fake writing like a different author, essentially fooling the different kinds of stylometric tests on offer. The study I linked above doesn’t quite examine what we’re talking about in the Book of Mormon (as it looks at correctly identifying a particular author among a set of candidates rather than multiple authorship, and has atrocious word-sample sizes for its test texts; it also generally finds that the methods used by the faithful scholars above are the most resistant to fakery), but that wouldn’t stop an enterprising researcher from designing a study that better and more directly examines the type of fraud allegedly perpetrated by Joseph. The best idea of all, though, in my opinion, would be to do a stylometric analysis using other eighteenth- and nineteenth-century pseudo-biblical texts, to see if attempting to mimic biblical style could produce the kind of result we find with the Book of Mormon. My guess is that it wouldn’t. But, then again, the entire point of this exercise has been to look for things I wouldn’t expect to see.

Next Time, in Episode 12:

When next we meet, we’ll discuss the proposed similarities between the Book of Mormon and other nineteenth-century works, particularly View of the Hebrews and The Late War.

Questions, ideas, and semi-sharpened spoons can be thrust in the heart of BayesianBoM@gmail.com or submitted as comments below.

Appendix

Reading Kyler’s latest essay on stylometry triggered the memory of an article I read many years ago by Arthur Henry King. King was a convert to the Church, a former Quaker, and a very learned and accomplished stylistician.

In this wonderful article King states:

“By the test of stylistics, the Book of Mormon and Doctrine and Covenants are unique literary phenomena. They are quite different from Joseph Smith’s own prose and significantly different from the Bible and from each other. They could not have been invented by Joseph Smith, or (more important) by anybody else at that time or today, for that matter. Clearly the Lord made full use of Joseph Smith’s remarkable mind; but equally clearly, only through inspiration could that remarkable mind have been made full use of.”

Is King’s statement a data-driven “proof” of the Book of Mormon? Can it be reduced to numbers by the Bayesian approach? Perhaps not, but it is valuable nonetheless in this discussion if, as I assume, stylometry attempts to measure some of the aspects of stylistics in which Arthur Henry King was so well-versed.

Much less valuable than King’s learned opinion, but perhaps still useful to some readers, I offer my own opinion on the issue of style. I am a compulsive and eclectic reader and have been since my earliest years. When I first read the Book of Mormon at age 16, I had already read many hundreds of books, perhaps a thousand (mostly science fiction at that age). I knew that the style of sci-fi writers differed greatly. Robert Heinlein’s style was different than that of Poul Anderson and both were different from Isaac Asimov.

When I read the Book of Mormon for the first time I felt the difference between the “voices” of Nephi, of Jacob, of Alma, of Mormon and his son Moroni. And all of these prophets have a different “voice” than that of Joseph Smith. As I have gotten older their individual voices have become even clearer and more distinct. They speak to me as individuals.

My point is that we often can know things that we cannot explain very well and/or cannot quantify. I know that the Book of Mormon had multiple authors…independent of what stylometry tells me.

Links:

https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/ensign/1989/03/a-man-who-speaks-to-our-time-from-eternity?lang=eng

https://mormanity.blogspot.com/2015/03/great-literature-you-may-have-missed.html

Bruce,

You sound an awful lot like me. I too grew up reading voraciously, largely science fiction and fantasy especially in the earlier years. More non-fiction the past decade or three. Unfortunately I just had to give away my 50-year collection of about 3,500 books (I only kept the best) because we are downsizing our home. Sniff. Fortunately most of them went to my sons.

Like you, I have often thought how different are the voices in the Book of Mormon from each other, and each so very different from the voice of Joseph Smith when he was writing as himself. I am convinced that not only was he not the author of the Book of Mormon, he could not have been. The same goes perhaps to a lesser extent for the Doctrine and Covenants.

Best Regards,

Dave C

Dave,

Thanks for the response. Yes, whatever else one may say about the Book of Mormon, to me, it clearly had different authors.

As for giving up your books, I feel your pain. 🙂

Bruce

Hi Kyler,

Two points on this one:

First, you are committing the sharpshooter fallacy again. And again, there is a fundamental contradiction between your verbal argument and your math. In theory, you are supposed to set the probability of CH *before* you look at the evidence (for the benefit of our readers, CH is the Consequent Probability of the Hypothesis, i.e. the probability of observing the stylometric evidence we have if the BoM is true). In this particular case, you set p = 1 for the CH. This means that there is a 100% chance a “true” BoM would *precisely* have the stylometric pattern that emerged. It *also* means that there is a 0% chance that a true BoM would have any other stylometric pattern. In other words, if Wayne Larsen would have come up with a slightly different set of odds, that would be enough to definitively prove the BoM was false. That is what your math implies.

However, that is the precise opposite of what you verbally say in your paper. You said, “signs of single-authorship or of the text matching Joseph’s style would’ve been far from fatal to theories of Book of Mormon authenticity.” If you really believe that signs of single-authorship aren’t fatal to your theory, you have the obligation of expressing that in your math. The result of including it in a proper way would severely curtail your results on this point.

Second, your “the BoM is true” hypothesis here is wildly inconsistent with your past two episodes. Then, the BoM being true meant there was an extremely loose translation process—even though they (the ghost committee) had a pristine ancient version of Isaiah from the golden plates and the wherewithal to translate it, they decided to replicate the errors in the KJV Bible instead. And according to Royal Skousen, this 16th century ghost committee took the liberty of writing about 16th century religious issues in the BoM. According to his theory, the BoM is best thought of 16th century protestant fiction that is loosely based upon what was on the actual gold plates.

That was your hypothesis last week. Now you’ve changed it. The translation is no longer extremely loose. Now it is extremely tight. Now you are claiming that if Nephi, Omni, Alma the Younger and Moroni have a slightly different way of expressing an idea, these distinctions must have been accurately reflected in what was written in reformed Egyptian, which then must have been reflected in what was translated.

Logic requires us to be consistent here, and I’m sticking with the loose translation hypothesis since that is what’s now in style among apologists. If it is wildly improbably for Joseph Smith as author to produce the stylometric patterns we see in the BoM, it would be equally improbable for the ghost committee to produce those same patterns in their loose translation. Therefore, those two unlikely things have no bearing on the ancientness of the BoM one way or another. My odds remain unchanged. I’m still at 40-million-to-one.

Thanks Billy, as always.

“In this particular case, you set p = 1 for the CH. This means that there is a 100% chance a “true” BoM would *precisely* have the stylometric pattern that emerged.”

In this case, it just means that I don’t see (and find it difficult to posit) a statistical basis for putting that value much lower than 1. From what I can tell, we’d fully expect an authentic BofM to exhibit stylometric evidence similar to what scholars have actually turned up. I could find ways to be more conservative on this point, but I’m already being quite conservative in other areas here. I also grant this grace quite often to the negative evidence (often in cases where I think it’s not fully justified), and I didn’t see you complaining about it then.

“That is what your math implies.”

It’s not what my math implies. What there is is an implied distribution of stylometric variation for multiply-authored works, a distribution which would include an authentic Book of Mormon. I don’t know what that distribution is, but it seems to me that the findings of Larsen and others would fit comfortably in that distribution. In part because I don’t know what that distribution fully looks like, I have no basis for saying otherwise, and in my view a CH of 1 is acceptably close to the mark.

“there was an extremely loose translation process”

Yet still a translation that remained largely responsive to the underlying text–responsive enough to maintain things like large scale Hebrew poetic elements, and a number of other proposed Hebraisms and Egyptianisms. Turns out both those things can be true at the same time. There’s no reason to think that Reformed Egyptian didn’t have the sort of non-contextual words analyzed with stylometry (since both Hebrew and Egyptian do), or that the translators wouldn’t have translated them in a consistent way.

With the King James quotations, the translators would’ve had reason to do things a bit differently. And since the King James quotations are often explicitly excluded by stylometric analysis, that sort of special treatment wouldn’t be relevant to what we observe in this class of evidence.

“even though they (the ghost committee) had a pristine ancient version of Isaiah from the golden plates”

I do believe that I posited something close to the opposite of this.

“they decided to replicate the errors in the KJV Bible instead”

And the closer I look at those errors, the less like errors they seem. Even when taking a look at the underlying Hebrew (which I tried to, in many cases), I had a grant count of 1 that I would’ve bothered to translate differently if I was in the translators shoes.

“Now you are claiming that if Nephi, Omni, Alma the Younger and Moroni have a slightly different way of expressing an idea…”

If you read the essay a little closer, you’ll notice that we’re not talking about “expressing ideas”, which would imply context-laden word choice. We’re talking about non-contextual words, which are as far away from the expression of ideas as you can get. Those individuals could definitely have different patterns of using those non-contextual words, and those words could’ve been translated in consistent ways, even if the word choice for more contextual words and ideas was subject to interpretation by the translators.

“it would be equally improbable for the ghost committee to produce those same patterns in their loose translation.”

Which reminds me of one idea that I didn’t mention, which is that a group of diverse EModE translators could’ve potentially contributed to the diversity of stylometric patterns that we see. I don’t see how my previous hypotheses are at all incongruous with the ones I’ve posited here.

Cheers!

Hi Kyler,

I started with your 0.00002 number and worked backwards. I was able to figure out that your analysis is based upon the article attributed to “BMC Team”, where they claim the “Standardized Volume” of five 19th century authors ranges from 2.93 to 1.09. If you exclude the “Standardized Volume” of the BoM from the list, you got the mean and sample standard deviation that you reported here. You assumed a normal distribution (an assumption strongly in favor of the historicity position, btw).

Here is my question. What, specifically, is “Standardized Volume” in this context? BMC Team didn’t define it in their article, and the three articles under “further reading” at the bottom don’t define it, either. A Google Search of “Standardized Volume” in the context of stylometry doesn’t provide any help.

It seems to me that if the “Standardized Volume” in this context really were a thing and 19th Century authors strictly have a Standardized Volume that is normally distributed with a mean of 1.48 and a S.D. of 0.34, this would be big news in the academic community.

Taking a step back, the assumptions that go into all of this seem quite suspect. The articles on stylometry typically qualify the results of their findings, and those qualifications are not reflected in your math.

My inclination on how to appropriately evaluate this in a Bayesian context is to dampen your results according to how likely (or unlikely) the underlying assumptions are to be true.

For example, if we estimate there were a 10% chance your assumptions on this point are true (i.e. there is a 10% chance that “Standardized Volume” is a thing, that it really is normally distributed, and that it really has the mean and S.D. you estimate), the dampened probability would be:

.90*(1.00) + .10*(0.00002) = 0.9.

Changing your 0.0002 to a 0.9 in this fashion may seem arbitrary and unfair, but the fact remains that there *could* be naturalistic explanations for the BoM having a “Standardized Volume” of 2.93 other than being by chance in the top 99.999% of 19th century books. These other explanations, both known and unknown, need to be taken into account.

This issue seems to be highly correlated with the first couple of episodes–somebody with the skill to write a Book as long as the Book of Mormon as quickly as he did is probably much more likely than the typical author to have the skill of creating a “Standardized Volume” of 2.93.

But this is all tentative. If I can’t independently verify what your numbers are actually referring to, my ability to evaluate this is dead in the water.

At last! Substantive questions dealing with the content of the essay!

“What, specifically, is “Standardized Volume” in this context?”

You’d have to get in touch with Roper or Fields on that one. I agree that it’d be very interesting to dig into the methodology on this. From my understanding, this was still research-in-progress at the time the BMC article was written. Maybe Fields talked more about this in his recent conference talk, but I didn’t see it, so I’m not sure.

“Changing your 0.0002 to a 0.9 in this fashion may seem arbitrary and unfair.”

And it is. What you’re essentially saying isn’t that there’s a 90% chance that the Mean and SD aren’t exactly correct (which of course they’re not). You’re saying that there’s a 90% chance that this data is completely uninformative on the question of multiple authorship. That’s not just betting that I’m a little off base in my estimates. It’s betting, on the basis of nothing but your own (assuredly righteous) desires, that Larsen and Hilton and Fields and everyone that’s ever done work in this space is entirely out to lunch.

If I’m ever that arbitrarily unfair to the critical position, please call me out on it, and then proceed to present me with the dingiest gutter-strewn head covering you can find for me to consume.

Could you please fix the link to the study from Fields, Bassist, and Roper? It just opens this same Interpreter article.

Thanks

I apologize. I missed this link plus a number of others. They have all been repaired.

Thanks for your tireless efforts Alan!

Well done. However, it would have been nice to see the results of a comparison of the Book of Mormon with William Caxton’s English translation of The Golden Legend (1483).

Thanks Robert, though I’m not familiar with the Golden Legend or its connection to stylometric analysis. I took a brief look to see if I could find anything, but couldn’t turn anything up. Is this an analysis that’s already been completed, or is it just one that you would find particularly relevant and interesting? If it’s the former, I’d love to take a look at it. If it’s the latter, I agree that it’d be a useful comparison.