Intro/FAQ ⎜ Episode 1 ⎜ Episode 2 ⎜ Episode 3 ⎜ Episode 4 ⎜ Episode 5 ⎜ Episode 6 ⎜ Episode 7 ⎜ Episode 8 ⎜ Episode 9 ⎜ Episode 10 ⎜ Episode 11 ⎜ Episode 12 ⎜ Episode 13 ⎜ Episode 14 ⎜ Episode 15 ⎜ Episode 16 ⎜ Episode 17 ⎜ Episode 18 ⎜ Episode 19 ⎜ Episode 20 ⎜ Episode 21 ⎜ Episode 22 ⎜ Episode 23

[Editor’s Note: This is the first in a series of 23 essays summarizing and evaluating Book of Mormon-related evidence from a Bayesian statistical perspective. See the FAQ at the end of the introductory episode for details on methodology.]

The TLDR

It seems unlikely that a young man of Joseph Smith’s limited education could produce a book the length of the Book of Mormon as a first-time author.

Joseph Smith is a definite outlier among the nineteenth-century’s great authors, even without considering the extraordinary content of the book itself. The estimated probability that someone of Joseph Smith’s age and education would publish a book the size of the Book of Mormon as their first work is p = .0006.

Evidence Score = 3 (beliefs adjusted 3 orders of magnitude toward authenticity)

The Narrative

Imagine yourself on a dark, cold night in New England, 1835. Your hearth dances with faint light from a dying fire, and you huddle next to it with a thick wool blanket, trying to keep warm. As you stare at the coals you find your eyes wandering to a Bible, open on the table to where you’d last been reading. Dust skirts the wrinkles of the paper, catching the light from the fire. You turn away quickly, the edge of your cheek twitching with the hint of a grimace.

As you sit, a muffled knock works its way through the heavy wood of the cabin door. A moment’s silence hangs in the air, and you hope that silence will keep, but the knock repeats—a more desperate knock this time.

"What is it?" you yell out grumpily toward the door. "You picked a cold night for visiting."

The voice of a young man responds with deference. "My apologies. I was told in the village that you had an interest in rare and unusual books. I have one that I think you might like to see."

Your eye edges again to the Bible on the table, and your exhaling breath turns to an audible sigh. "You’re mistaken, young sir. I’m not in the habit of entertaining booksellers on my doorstep, let alone at this late hour."

"Please", the voice says, quieter this time. "The night is cold, and I have no friends in this place. If you would allow me to warm myself by the fire a moment, it would help speed me on the road back to town."

You take another moment before pulling yourself off your hard wooden chair. You pull the door open and do your best to put on a more welcoming face. "Thank you", the young man says, though a creeping baldness at the edges of his dark hair tells you he’s not as young as he sounds. You move another chair by the fire and motion him to sit. He does, his eyes grateful. "The Lord bless you for your kindness."

You keep your eyes on him as he watches the coals, rubbing the chill from his hands. He doesn’t seem as keen to talk as a bookseller might be. "Well then," you say, "as long as you’re here you might as well pull out that book."

He looks back at you almost in surprise, but dutifully moves his stiff hands to his satchel. Those hands pull out a book, small but thick, its cover red in the light of the fire. You can’t quite read the title in the dim light. "And what is that?" You ask.

"This," he says, "is the Book of Mormon."

The words hold no meaning for you, but you listen as he tells you about the book. He says that it’s a volume of scripture, one that tells of the ancient inhabitants of the American continent and their visit by Christ following his resurrection. He says that the book is evidence that God has called a new prophet—a modern Moses—to restore the Church of Jesus Christ to the earth.

You can’t help but let out a chuckle at that last part. This Joe Smith wouldn’t be the first rabble-rousing prophet you’d heard of, and he wouldn’t be the last. Still, none of them had a book like this. You take the book in your hands, running your fingers the length of the spine. You open it and flip through the pages—hundreds of them filled with a tightly packed script. You know that writing such a thing would be no mean feat.

You close the book and face the young man, who you know can see your skepticism. “This Smith fellow, how old was he when this book was published?”

He eyes turn upward in thought. “That was five years ago now, which would have made him 24.”

“And where was he educated? Harvard? Princeton?”

The young man’s head gives a shake, and a laugh comes with it. “If you had ever seen him write you wouldn’t have asked. He saw enough school to learn his letters, but he didn’t learn them very well.”

“Hmm,” you say, continuing to run your fingers along the book’s spine. “I suppose it does seem unlikely that a young man with so little schooling could have written something like this.”

The Introduction

That last statement is the sort of thing I could imagine anyone saying to themselves the first time they encounter the Book of Mormon. Those that early missionaries approached on the American frontier certainly thought similar things. Judging by the arguments they make, many critics of the Book of Mormon think it rather strongly. Its why so many have searched for so long (and so unsuccessfully) for someone else on whom they can pin the book’s authorship. And phrased as it is above, I think it’s something everyone on all sides should be able to agree on—it does seem unlikely. The question is, is it actually unlikely, and how unlikely is it?

That’s a big question. I’m only going to tackle a part of that question here, and it’s the most basic part. Given Joseph’s age and education, how unexpected would it be for him to write a book the length of the Book of Mormon, with no prior history of publication (or of, you know, coherent and well-worded letters). As hopefully you know by now, given the introductory episode, we’re going to use Bayesian analysis to help answer that question.

Now, to clarify, when I talk about “length,” I mean it literally—we’re going to base our analysis on the word count within the Book of Mormon and within other nineteenth-century works—but I also mean something more than that. The Book of Mormon is much more than just a large collection of words. It’s a complex web of history, narrative, and sermon that gives it a deserved place in literature’s great epics. That narrative complexity is much more difficult to quantify than word count, but it’s a point on which few seriously contend, and it’s worth noting as we leave that complexity behind to focus on its raw size.

The Analysis

I know this is the first episode where I actually get into some Bayesian analysis, but I really recommend taking a glance at my FAQ in the introductory episode before you go much further. It should help you get your bearings on the type of analysis I’m trying to do here and what all these terms and formulas mean. I also know that no one ever clicks on links, so I’m going to try to take things slow here, but you can’t say I didn’t warn you.

First, we have to think clearly about the evidence we have at hand—in this case, the sheer size of the Book of Mormon along with Joseph’s age and education at the time it was published.

The Evidence

The Book of Mormon is about 268,163 words long, taking up 531 (very dense) pages in its current edition. You’re not likely to get through it in a breezy afternoon reading session. It was also the first written work he ever produced, which is relevant given that most authors have early projects that prepare them for their eventual masterpieces. Joseph Smith’s magnum opus came out of nowhere and, aside from scattered revelations (including the Joseph Smith Translation), sermons, and the relatively brief Book of Abraham, his writing career ended almost as quickly. We could potentially account for these additional works in his word count, but what we’re most interested in here is the debut production of an author. Similar analyses could be done for other aspects of an authors’ writings, such as lifetime composition, but that would be unlikely to help the critics’ case, given how unique Joseph’s writing career is in that regard. We’ll keep it simple and stick with the Book of Mormon itself.

The publication of the Book of Mormon was completed when Joseph Smith was 24, though its dictation took place when he was 23. We’ll go with 24 just for the sake of argument, though. It’s commonly claimed that Joseph Smith had three years of formal education, and if we’re trying to align it with an equivalent public school education today, that’s probably not far off. If we’re trying to be technical about it, though, there were seven distinct years in which he received some sort of schooling, including a season in high school when he was 20. We’ll stick with seven years of education for this particular analysis.

If you’re interested in a more in-depth discussion of additional literary characteristics (e.g., reading level; lifetime composition) of the works attributed to Joseph Smith, this one by Brian Hales is a fantastic place to start.

So that’s the evidence as we seem to have it, and on which reasonable people can likely agree. Now, what explanations do we have for that evidence?

The Hypotheses

Joseph Smith as author of the text—According to this theory, Joseph Smith was the sole author of the text and, having produced it, should be considered among the great literary talents of the nineteenth century.

The Book of Mormon as an authentic ancient text—If this theory is correct, Joseph Smith was not the author of the Book of Mormon. The book was instead written by two-dozen authors over a period of a thousand years, and was edited and abridged by an ancient scribe who made doing so his life’s work. There would be no reason to expect the length of the Book of Mormon to align with nineteenth-century literary works.

In addition to these two theories, many have made arguments over the years that some other individual, such as Sidney Rigdon, was the author of the text. Though the available primary evidence doesn’t align well with that theory (and arguments for Sidney’s authorship seem particularly weak), it would be possible to adjust my analysis for any given author by replacing Joseph’s age and education with theirs. As we’ll see, though, age and education don’t end up making much of a difference. Theories that suggest multiple nineteenth-century individuals collaborating to create the book have similar evidentiary problems, and would probably require a different analysis (comparing the Book of Mormon to other collaborative works of fiction, which might be a bit tougher to track down). I’ll be focusing this analysis on Joseph, and let others take up alternative torches if they so desire.

So, given those two competing theories and our background knowledge, how probable would we consider those hypotheses at first blush, before considering any of the evidence?

Prior Probabilities

*Note: If we were doing a complete Bayesian analysis, we would spend more time trying to produce reasonable estimates for these values. But given that no one will ever agree on the likelihood of stuff like angels or seer stones, I’ve opted to use prior probabilities to demonstrate a type of faith journey. As we consider more evidence, both for and against the Book of Mormon, we can track how those beliefs change. Starting with a position of extreme skepticism and having the evidence alter that probability allows us to see that change in action.

PH—Prior Probability of Ancient Authorship—We start with the assumption that the probability of ancient authorship is low to the point of vanishing (1 in 1040, or p = 1.0 x 10-41).

PA—Prior Probability of the Alternative (Joseph Smith Authorship)—If we assume the probability of ancient authorship is low, then that means we’re assuming that the probability of Joseph Smith authoring the document is high (i.e., extremely close to 1, or, if you want to be a bit more precise, p = 1 – 1.0 x 10-41).

Consequent Probabilities

CH—Consequent Probability of Ancient Authorship—How likely would it be for the Book of Mormon to be its size if it was authored anciently? Well, if Joseph Smith didn’t write the Book of Mormon, then his own age and education aren’t relevant, so we can just leave those factors out. We would instead expect the length of the book to look much more like a collection of scriptural texts than a nineteenth-century work of fiction.

So how does the Book of Mormon compare to that type of collection? The Bible seems like a pretty useful reference in this case, and it makes sense to take a look at it at the level of individual books within the Bible and Book of Mormon (see Table 1 in the Appendix). The average book in the Book of Mormon has 17,989 words, which is obviously more than the Bible’s 11,943 words. However, the word count in the books of the Bible has quite a range, and the standard deviation is 12,352. That would put the Book of Mormon’s count well within a single standard deviation of the Bible’s average, which suggests that the Book of Mormon fits comfortably with what we’d expect for books of scripture.

We can go a step further, though, and estimate a more exact probability that the books of the Book of Mormon fall on the same distribution as the books of the Bible. Since the word counts of the books of the Bible and the Book of Mormon clearly don’t follow a normal distribution, that limits us a bit. But we can use a statistical test like the Independent Samples Mann-Whitney U Test to get what we need. When we conduct that particular test, the probability that the word count distribution differs between those sets of books is p = .535.

Now, that probability is likely too far on the low side—you could argue that the Book of Mormon is structured more like the Old Testament than the New (i.e., as weighted more heavily toward lengthy scribal abridgements than toward brief personal letters). If you only include the books of the Old Testament, the Book of Mormon would look even more similar to the Bible. But we’ll give the critics the benefit of the doubt and stick with our .535 value.

And that fits what would likely be our gut expectation here—if we had a volume of ancient scripture like the Book of Mormon, it wouldn’t be guaranteed to be the size the Book of Mormon actually is, but that sort of length wouldn’t be unexpected by any stretch.

CA—Consequent Probability of Modern Authorship—Now how likely would it be for the Book of Mormon to be its size if it was the product of a single nineteenth-century author of Joseph Smith’s age and education? To figure that out we have to take a close look at some other nineteenth-century authors. I’m not the first to do so, but there may be a few things I can add to what’s come before.

To do that, I relied on this handy Wikipedia list of prominent literary works produced in each decade going back to 1500. It provides a useful sample of highly respected authors within Joseph Smith’s timeframe and, sure enough, Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon are right there on the list. I took the 116 authors with works published between 1800 and 1860 and used their individual Wikipedia entries (supplemented by Encyclopedia Britannica, when necessary) to keep track of three things: how old they were when they published their first fictional work (of greater than 50 pages), how long that work was (in pages), and how many years of formal education they received (see Table 2 in the appendix).

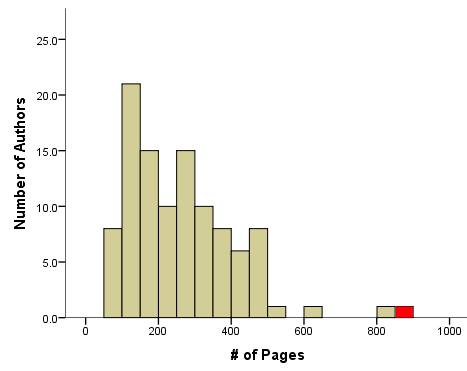

Now, there are some limitations there to keep in mind. Because I was working with page counts rather than word counts, it was important to get a comparable page count for the Book of Mormon. The Book of Mormon’s pages are quite a bit denser than the average book. If it did have the average number of words per page (which readinglength.com calculates at about 306) it would have 876 pages instead of 531. I also didn’t have precise publication dates for the books, which meant I calculated age at publication by subtracting the birth year from the publication year for each author. Education was tricky as well—some entries didn’t include exact information on formal schooling (particularly for the female authors). I picked the lowest number of years I could justify based on the information available.

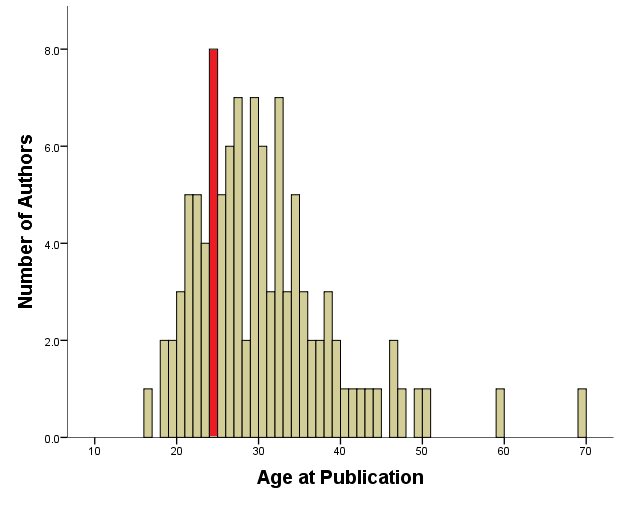

All told, it was a horrifically interesting Wiki-binge. A couple things stood out pretty clearly by the end. First, 24 is young for a first-time author, but not horrendously young, and even turned out to be the modal age. The average age at publication was 30, but there were some as young as 16. (In all of the following charts, the red bars indicate where Joseph and the Book of Mormon fall in the distribution of data.)

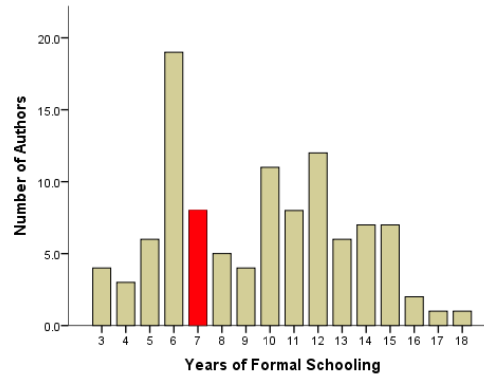

Second, many of the authors were university educated, and those who weren’t had the benefit of extensive private tutoring. None of them could be plausibly labeled as a country bumpkin. Even those with more spotty education were described as voracious readers as children and were recognized early for their precocious talents (very much in contrast to Joseph Smith). For those with private tutoring, I assumed (conservatively) they had the equivalent of a sixth-grade education.

It’s important to keep in mind, too, that the primary argument about Joseph Smith’s education isn’t that he was too uneducated to write a book. It’s that he didn’t have the very specific education required to produce some of the book’s more impressive (and ancient) literary features. Demonstrating that some other prominent authors had even less education than he did does nothing to counter that argument.

And if we just look at page counts, Joseph Smith is clearly exceptional as a first-time author. Only one comes close to matching his output, and that’s the incomparable Charles Dickens, who seemed to do little else other than write his brain to pieces. I should note, though, that Dickens was about the same age as Joseph at the time his first novel was published, and himself had an atrocious education.

Now, before any critics get too excited, it’s important to keep a few things in mind. Dickens was one of those precociously talented, voracious readers mentioned above. He also wrote his first novel in monthly installments as a serial, being paid for each installment, over a span of 20 months. That may sound quick, but it’s got nothing on Joseph’s 65 working days. Dickens was exceptional in his own right, in part due to a medium that incentivized producing a ton of material. I wouldn’t use him as proof that Joseph could’ve written the Book of Mormon.

Once I had that lovely little dataset, though, I used a form of outlier analysis using a measure called the Mahalanobis Distance to estimate how likely it is that Joseph Smith belonged in the group of nineteenth-century literary masters. When I conduct this sort of analysis in my research, I’m generally looking to see if there are any odd ducks in my data—anything that doesn’t seem to “fit” with the rest of what I’m looking at. The analysis shows me the probability that a particular case belongs to the same distribution of data as the rest of the cases in the dataset. Usually, if that probability is less than 1 in 1000, I’ll toss it aside so it doesn’t mess up the rest of my analyses.

All told, Joseph is a clear outlier. He was younger than average, had substantially less education than average, and, taking all that into account, produced a work far larger than anyone would have guessed. He had a Mahalanobis Distance of 17.5, which, when plugged into a chi-square test with three degrees of freedom (for the number of variables in the analysis), reveals a probability of p = .00055. In other words, we would expect about 55 in 100,000 first-time authors of his age and education to publish a work with the length of the Book of Mormon.

For those who are curious, there was only one other actual outlier in the analysis, but he was an outlier for a different reason. Johann David Wyss wrote his first novel, The Swiss Family Robinson, at the ripe age of 69. If you take out Joseph Smith, then Dickens himself becomes an outlier with a probability of p = .0002, but he makes somewhat less of a splash (p = .001) in a world where the Book of Mormon exists. None of our other candidates even comes close to being an outlier.

(And if it seems like it would be possible to fiddle with the analysis and change the results depending on which books we included, you’re right—it would. Which is why it’s important that I’m not hand-picking—or, if you prefer, cherry picking—which books make it in and which don’t. Basing my sample on Wikipedia entries helps avoid that kind of tom-foolery.)

We can do some further analyses to get a sense of which of those three characteristics—education, age, and length—are contributing most to Joseph’s outlier status. We can remove each of those variables from the analysis, one at a time, and see what happens to the probability when we do. As we might expect from the figures above, removing education and age doesn’t change much—in fact, the probability gets lower (p = .00016 and .00031 respectively). That means the Book of Mormon’s length is what’s setting it apart as an outlier. When we remove length from the analysis, it doesn’t seem like much of an outlier at all (p = .65). It turns out that considering his age and education actually worked a little in favor of the critics, which is a bit surprising given how often the faithful tend to play those things up.

Overall, however, it still seems quite unlikely that any nineteenth-century author would have produced a book with the length of the Book of Mormon as a first-time work. And my estimate, again, is a conservative one—the real probability is probably even lower than that. The power to detect outliers increases as the sample size increases, so odds are good the probability would decrease further if I considered more authors.

Posterior Probability

So what does all this mean for our beliefs about the Book of Mormon? Now we get to plug all those values into Bayes’ formula and see what happens:

PH = Prior Probability of the Hypothesis (1 in 1040 chance of ancient authenticity, or p = 1.0 x 10-41)

CH = Consequent Probability of the Hypothesis (the probability of an ancient collection of records being as long as the Book of Mormon, or p = .535)

PA = Prior Probability of the Alternate Hypothesis (1 – 1.0 x 10-41 chance of Joseph Smith as author, a very very high initial estimate)

CA = Consequent Probability of the Alternate Hypothesis (our estimate of the probability of a first-time nineteenth-century author publishing a book as long as the Book of Mormon, given his education and age, or p = .00055)

PostProb = Posterior Probability (the new probability of Book of Mormon authenticity)

| PH = 1.0 x 10-41 | |

| PostProb = | PH * CH |

| (PH * CH) + (PA * CA) | |

| PostProb = | 1.0 x 10-41 * .535 |

| (1.0 x 10-41 * .535) + ((1-1.0 x 10-41) * .00055)) | |

| PostProb = | 9.99 x 10-39 |

We can also calculate the “likelihood magnitude,” or an estimate of how many orders of magnitude the probability changes when we consider this evidence.

Lmag = Likelihood Magnitude (an estimate of the number of orders of magnitude that the probability will shift, due to the evidence)

Lmag = log10(CH/CA)

Lmag = log10(.535/.00055)

Lmag = log10(972)

Lmag = 3

Conclusion

It may not look like much happened there. At first glance, you might think that we started with an incredibly small probability of an authentic Book of Mormon and ended up with an incredibly small probability of an authentic Book of Mormon. But after reviewing the evidence, our extreme skeptic would have increased his estimate of an authentic Book of Mormon almost a thousand-fold—a change of about three orders of magnitude. If we were dealing with someone less skeptical—say, someone who gave the Book of Mormon only a 1 in 100 chance of being ancient, just the length of the Book of Mormon alone could be enough to move them to over 90 in 100 odds that it was ancient. That’s not nothing. And that’s all before we even consider what’s actually in the book, or even how the book was translated.

Did I just use Wikipedia to prove that the Book of Mormon is ancient? No. It would be very easy for the actual content of the Book of Mormon to betray itself as a fraud. This is just one piece of a very large corpus of evidence, both scholarly and less so. But it shows how it would be reasonable for someone to pick up the Book of Mormon and get the sense that they should take it seriously. It sets the first block in a foundation of reasoned skepticism—not skepticism of the church’s truth claims (there’s plenty of that to go around), but a skepticism that questions the claim that the Book of Mormon is a modern artifact of nineteenth-century origin.

Skeptic’s Corner

Just so I don’t give you the impression that my analyses are law, with each essay I’ll be taking a minute to more explicitly play the role of skeptic, discussing aspects that I think could be improved or that deserve a bit more investigation. In this case, if I was a critic, I’d wonder how the Book of Mormon stacked up against twentieth- and twenty-first-century authors, to know whether Joseph is still an outlier in that context. It’d also be useful to get a sample of amateur rather than professional authors—perhaps the book’s length could be attributable to his lack of taste or his unrefined literary sensibilities (though whether that supposition would line up with the book’s other qualities is a separate question). And of course, using actual word counts instead of estimated page counts would be helpful as well.

It’s worth noting, too, that considering things like reading level or lifetime composition has a real shot at making this type of evidence much, much stronger. It seems very unusual for someone to have produced so much by the age of 24 and then to write little else to compare to it. It wouldn’t take much to statistically compare authors’ lifetime trajectory of work, similar to how Brian Hales plotted them in his Interpreter article, but we’ll leave such questions for another time (or for others to tackle at their convenience).

Next Time, in Episode 2:

Next week, our skeptic will encounter Joseph’s multiple accounts of the First Vision, and we’ll estimate the probability of producing highly disparate and even contradictory accounts when telling a story years apart in different settings.

Questions, ideas, and sharp objects can be flung in the direction of BayesianBoM@gmail.com or submitted as comments below.

Appendix

Table 1. Scriptural Word Counts

| Number | Book | Word Count |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Genesis | 38262 |

| 2 | Exodus | 32685 |

| 3 | Leviticus | 24541 |

| 4 | Numbers | 32896 |

| 5 | Deuteronomy | 28352 |

| 6 | Joshua | 18854 |

| 7 | Judges | 18966 |

| 8 | Ruth | 2574 |

| 9 | 1 Sam | 25048 |

| 10 | 2 Sam | 20600 |

| 11 | 1 Kings | 24513 |

| 12 | 2 Kings | 23517 |

| 13 | 1 Chron | 20365 |

| 14 | 2 Chron | 26069 |

| 15 | Ezra | 7440 |

| 16 | Nehemiah | 10480 |

| 17 | Esther | 5633 |

| 18 | Job | 18098 |

| 19 | Psalms | 42704 |

| 20 | Proverbs | 15038 |

| 21 | Ecclesiastes | 5579 |

| 22 | Song of Solomon | 2658 |

| 23 | Isaiah | 37036 |

| 24 | Jeremiah | 42654 |

| 25 | Lamentations | 3411 |

| 26 | Ezekiel | 39401 |

| 27 | Daniel | 11602 |

| 28 | Hosea | 5174 |

| 29 | Joel | 2033 |

| 30 | Amos | 4216 |

| 31 | Obadiah | 669 |

| 32 | Jonah | 1320 |

| 33 | Micah | 3152 |

| 34 | Nahum | 1284 |

| 35 | Habukk | 1475 |

| 36 | Zephen | 1616 |

| 37 | Haggai | 1130 |

| 38 | Zechariah | 6443 |

| 39 | Malachi | 1781 |

| 40 | Matthew | 23343 |

| 41 | Mark | 14949 |

| 42 | Luke | 25640 |

| 43 | John | 18658 |

| 44 | Acts | 24229 |

| 45 | Romans | 9422 |

| 46 | 1 Cor | 9462 |

| 47 | 2 Cor | 6046 |

| 48 | Galatians | 3084 |

| 49 | Ephesians | 3022 |

| 50 | Phillip | 2183 |

| 51 | Collos | 1979 |

| 52 | 1 Thess | 1837 |

| 53 | 2 Thess | 1022 |

| 54 | 1 Tim | 2244 |

| 55 | 2 Tim | 1666 |

| 56 | Titus | 896 |

| 57 | Philem | 430 |

| 58 | Hebrews | 6897 |

| 59 | James | 2304 |

| 60 | 1 Peter | 2476 |

| 61 | 2 Peter | 1553 |

| 62 | 1 John | 2517 |

| 63 | 2 John | 298 |

| 64 | 3 John | 294 |

| 65 | Jude | 608 |

| 66 | Revelation | 11952 |

| B01 | 1 Nephi | 26498 |

| B02 | 2 Nephi | 30789 |

| B03 | Jacob | 9476 |

| B04 | Enos | 1209 |

| B05 | Jarom | 773 |

| B06 | Omni | 1468 |

| B07 | Words of Mormon | 889 |

| B08 | Mosiah | 32408 |

| B09 | Alma | 88358 |

| B10 | Helaman | 12288 |

| B11 | 3 Nephi | 30060 |

| B12 | 4 Nephi | 2036 |

| B13 | Mormon | 9865 |

| B14 | Ether | 17271 |

| B15 | Moroni | 6454 |

Table 2. Early 19th Century Authors

| Author | Book | Years of Formal Schooling | Age at Publication | Pages | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joseph Smith | Book of Mormon | 7 | 24 | 876 | |

| Maria Edgeworth | Castle Rackrent | 7 | 32 | 176 | |

| Friedrich Schiller | Die Rauber | 13 | 22 | 168 | |

| Walter Scott | Waverly | 14 | 43 | 528 | |

| Francois Rene de Cautaubriand | Atala | 10 | 33 | 160 | |

| Germaine de Stael | Could not locate. | ||||

| Jane Porter | Thaddeus of Warsaw | — | 26 | 267 | No mention of formal education, but would have been tutored extensively. |

| Jean Paul | Gronlandische Prozesse | 6 | 20 | 212 | |

| Charles Brockden Brown | Alcuin | 6 | 27 | 106 | |

| Elizabeth Helme | Louisa; or the Cottage on the Moor | — | 34 | 286 | No mention of formal education, but would have been tutored extensively. |

| William Blake | Did not produce novel-length works | ||||

| Jean-Baptiste Cousin de Grainville | Le Dernier Homme | 10 | 59 | 400 | |

| Elizabeth Meeke | Count St. Blancard | — | 34 | 100 | No mention of formal education, but would have been tutored extensively. |

| Heinrick von Kleist | Die Familie Schroffenstein | 9 | 26 | 114 | |

| Johann Wolfgang von Goethe | Gotz von Berlichingen | 13 | 24 | 130 | |

| Percy Bysshe Shelley | Zastrozzi | 13 | 18 | 138 | |

| Regina Maria Roche | The Maid of the Hamlet: A Tale | — | 29 | 256 | No mention of formal education, but would have been tutored extensively. |

| Lord Byron | Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage | 15 | 23 | 128 | |

| Jane Austen | Sense and Sensibility | 3 | 36 | 368 | |

| Johann David Wyss | Swiss Family Robinson | 10 | 69 | 496 | |

| Carles Robert Maturin | The Fatal Revenge | 10 | 27 | 448 | |

| René-Charles Guilbert de Pixérécourt | Could not locate. | ||||

| William Wordsworth | The Borderers | 15 | 27 | 140 | |

| E.T.A. Hoffmann | Fantasiestücke in Callots Manier | 11 | 38 | 220 | |

| Benjamin Constant | Adolphe | 6 | 49 | 128 | |

| Mary Shelley | Frankenstein | — | 21 | 288 | No mention of formal education, but would have been tutored extensively. |

| Washington Irving | Letters of Jonathan Oldstyle | 12 | 19 | 67 | |

| Alexander Pushkin | Ruslan and Ludmila | 10 | 21 | 134 | |

| Thomas De Quincey | Confessions of an English Opium Eater | 7 | 37 | 352 | |

| Clement Clarke Moore | Did not produce novel-length works | ||||

| Alexander Griboyedov | Woe From Wit | 12 | 28 | 204 | |

| James Fenimore Cooper | Precaution | 11 | 31 | 317 | |

| Mary Russell Mitford | Watlington Hill | 5 | 25 | 54 | |

| Alessandro Manzoni | Il Conte di Carmagnola | 12 | 34 | 142 | |

| Alfred de Vigny | Éloa, ou La Sœur des Anges | 11 | 27 | 62 | |

| Jane C. Loudon | The Mummy! | — | 20 | 340 | |

| Heinrich Heine | Gedichte | 11 | 24 | 64 | |

| John James Audubon | Did not publish fiction. | ||||

| Thomas Love Peacock | 6 | 30 | 112 | ||

| Stendhal | Armance | 7 | 44 | 170 | |

| Victor Hugo | Han d’Islande | 8 | 21 | 332 | |

| John Richardson | Tecumseh | — | 32 | 144 | |

| Carl von Clausewitz | Vom Kriege | 3 | 50 | 142 | |

| Nikolai Gogol | Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka | 8 | 22 | 190 | |

| Honoré de Balzac | Les Chouans | 10 | 30 | 204 | |

| Edgar Allen Poe | The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket | 11 | 29 | 288 | |

| Alexis de Tocqueville | De la démocratie en Amérique (Vol. 1) | 12 | 30 | 270 | |

| Karel Hynek Mácha | Maj | 15 | 25 | 100 | |

| Mikhail Lermontov | A Hero of Our Time | 9 | 25 | 208 | |

| Charles Dickens | The Pickwick Papers | 8 | 24 | 848 | |

| Charles Darwin | The Voyage of the Beagle | 10 | 30 | 448 | |

| Taras Shevchenko | Kobzar | 13 | 26 | 452 | |

| Richard Henry Dana Jr. | Two Years Before the Mast | 13 | 25 | 190 | |

| John Ruskin | The King of the Golden River | 7 | 22 | 52 | |

| Thomas Babington Macaulay | Lays of Ancient Rome | 12 | 42 | 148 | |

| Hans Christian Andersen | Did not produce novel-length works. | ||||

| Søren Kierkegaard | Did not produce novel length works. | ||||

| William Harrison Ainsworth | Rookwood | 12 | 29 | 430 | |

| Alexandre Dumas | Captain Paul | — | 36 | 108 | "Did not have much of an education." |

| Domingo Faustino Sarmiento | Facundo | 5 | 34 | 288 | |

| Benjamin Disraeli | Vivian Grey | 11 | 22 | 348 | |

| Henry Wadsworth Longfellow | Hyperion | 14 | 32 | 158 | |

| Charlotte Brontë | Jane Eyre | 7 | 31 | 492 | |

| Emily Brontë | Wuthering Heights | 3 | 29 | 416 | |

| Frederick Marryat | The Naval Officer | — | 37 | 288 | "Son of a merchant prince and member of parliament", so it’s likely he was well educated. |

| Anne Brontë | Agnes Grey | 4 | 26 | 192 | |

| Charles Kingsley | Yeast | 17 | 29 | 184 | |

| William Makepeace Thackeray | The Memoirs of Mr. C. J. Yellow-Plush | 14 | 26 | 474 | |

| Francis Parkman | The Oregon Trail | 16 | 24 | 178 | |

| Robert Browning | Paracelsus | 4 | 23 | 104 | |

| Nathaniel Hawthorne | The Scarlet Letter | 15 | 46 | 148 | |

| George Borrow | The Zincali | 12 | 38 | 296 | |

| Elizabeth Gaskell | Mary Barton | 6 | 38 | 464 | |

| Herman Melville | Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life | 7 | 27 | 368 | |

| Ivan Turgenev | Rudin | 18 | 39 | 88 | |

| Harriet Beecher Stowe | Uncle Tom’s Cabin | 15 | 41 | 266 | |

| Matthew Arnold | The Strayed Reveller, and Other Poems | 10 | 27 | 68 | |

| Charlotte Mary Yonge | Abbeychurch | — | 21 | 268 | Educated at home by her father studying latin, greek, french, Euclid, and algebra. Educated until she was 20. |

| Henry David Thoreau | A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers | 14 | 32 | 368 | |

| Walt Whitman | Franklin Evans | 5 | 23 | 208 | |

| Bozena Nemcova | Origin (including birthdate and identity) under dispute. | ||||

| Elizabeth Barrett Browning | The Seraphim, and Other Poems | — | 32 | 384 | Educated at home and tutored. |

| Fitz Hugh Ludlow | The Hasheesh Eater | 14 | 21 | 228 | |

| Thomas Hughes | Tom Brown’s Schooldays | 15 | 35 | 466 | |

| Charles Baudelaire | Fanfarlo | 12 | 26 | 80 | |

| Gustave Flaubert | Rêve d’enfer | 13 | 16 | 311 | |

| George MacDonald | Phantastes: A Fairie Romance for Men and Women | 15 | 34 | 158 | |

| Aleksey Pisemsky | Nina; The Comic Actor; An Old Man’s Sin | 6 | 30 | 184 | Was also tutored at home for several years. Couldn’t find his first novel, but I could find his second published a year later. |

| Alexander Ostrovsky | Did not produce novel-length works | ||||

| Ivan Goncharov | A Common Story | 14 | 35 | 264 | |

| George Meredith | The Shaving of Shagpat | 8 | 28 | 252 | |

| Wilkie Collins | Iolani, or Tahiti as It Was; a Romance | 5 | 20 | 250 | |

| Mary Anne Evans | Adam Bede | 11 | 30 | 608 | |

| Eduard Douwes Dekker | Max Havelaar: Or the Coffee Auctions of the Dutch Trading Company | 3 | 40 | 352 | |

| Antanas Baranauskas | Did not produce novel-length works. | ||||

| Ellen Wood | Danesbury House | — | 46 | 298 | No mention of education or tutoring. |

| Anthony Trollope | The Macdermots of Ballycloran | 5 | 32 | 364 | |

| Charles Reade | Peg Woffington | 16 | 29 | 106 | |

| Sheridan Le Fanu | The Cock and Anchor | 4 | 31 | 384 | Studied law at Trinity College. Was tutored previously (though ineffectively). |

| Charles Warren Adams | The Notting Hill Mystery | — | 32 | 176 | No mention of education. Couldn’t find a good page estimate for Velvet lawn, his first novel. |

| Nikolay Chernyshevsky | What Is to Be Done? | 12 | 35 | 464 | |

| Mary Elizabeth Braddon | The Trail of the Serpent | — | 25 | 496 | "Was privately educated." |

| Jules Verne | Un prêtre en 1839 | 12 | 19 | 249 | |

| Théophile Gautier | Mademoiselle de Maupin | 12 | 24 | 400 | |

| Jorge Isaacs | Maria | 9 | 30 | 336 | |

| Fyodor Dostoevsky | Poor Folk | 10 | 24 | 112 | |

| Lewis Carroll | Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland | 5 | 33 | 192 | |

| Algernon Charles Swinburne | The Queen Mother and Rosamund | 11 | 23 | 234 | |

| Karl Marx | The Holy Family | 12 | 27 | 116 | |

| Henrik Ibsen | Catiline | 9 | 22 | 125 | |

| Bret Harte | Condensed Novels and Other Papers | 7 | 29 | 332 | "Formal schooling ended when he was 13" |

| Louisa May Alcott | Moods | — | 33 | 178 | Tutored by her father and Henry David Thoreau |

| Edward Everett Hale | The Brick Moon | 14 | 47 | 232 | |

| R. D. Blackmore | Clara Vaughan | 10 | 39 | 336 | |

| Comte de Lautréamont | Les Chants de Maldoror | 8 | 18 | 342 | |

| Leo Tolstoy | Childhood | 10 | 24 | 336 |

I’m starting to wonder if Joseph’s authorship is a nuance parameter. (May need to use marginalization). What I’d be more interested in is who else authored the book. Evidence should point to Moroni and Mormon, if not, I’d better figure out whom instead or else the analysis is incomplete.

Please forgive me, it’s so weird applying probability to faith questions for me. I thought I’d be really into it, but the more I think about it, the more uncomfortable I feel. Maybe it’s the old Ecclesiastes proverb that with an increase of knowledge comes an increase in sorrow… I love that book. Maybe it’s time to start attending Elder’s Quorum again…

“I’m starting to wonder if Joseph’s authorship is a nuance parameter.”

Agreed that the question of potential 19th century authorship is extremely important. This is especially the case because critics tend to jump around to whichever candidate isn’t under present investigation. If you present evidence against Joseph they’ll jump to Oliver or Sidney. If you present evidence against Oliver or Sidney, they’ll, almost in the same breath, jump back to Joseph, without much self-awareness of this lack of consistency.

I don’t think there’s any question that Joseph is the prime suspect here, and so these analyses will frame the critical hypotheses in that light. But we can absolutely consider other possibilities. A question we can ask in each case that I think gets to the heart of the matter is this: “is there anyone we can identify for whom this evidence wouldn’t be unexpected?” In the present case, particularly because age and education swayed the analysis so little, I have a hard time thinking of an experienced author among the potential candidates whom I’d expect to produce a book of the size and scope of the BofM.

There are a couple pieces of evidence we’ll talk about here where we might consider meaningful alternatives (e.g., the dictation evidence), and some where alternatives are explicitly considered (i.e., stylometry), but for the most part the faithful evidence is grounded in the words of the book itself rather than in its author, and would apply equally to any potential 19th century candidate (e.g., Early Modern English, chiasmus, archaeological and thematic evidence, onomasticon, etc.). Anyone who would want to solve the problem of the BofM by finding a non-ancient, non-Joseph alternative should recognize the limitations of that approach, and these limitations find expression in the inability (so far) for critics to be able to build consensus (or even a coherent proposal) for any of those alternatives.

“Maybe it’s time to start attending Elder’s Quorum again…”

As a currently service EQP, I’m under professional obligation to say that you indeed should! They need you!

Cheers Quets!

Hi Kyler,

KR: If they’re not, either their prior isn’t really at 1 in 400, or the evidence isn’t actually hitting them at p = .0006, or they’re taking into account more information than merely its length.

I have two points. First, the evidence really isn’t at the p = 0.0006 level. Your analysis that came up with that number is flawed (the sample data is not normally distributed). Second, I don’t think this really has any bearing on authorship (19th Century authors are not homogenous).

KR: Actually, it assumes that they follow a given distribution on each of those three variables, which is a much more reasonable assumption than saying that they’re homogeneous on those characteristics.

The Mahalanobis Distance is simply a well-defined number that comes out of the mathematical calculations. But when you plug this number into a chi-squared test, you are implicitly assuming the underlying distribution is normal. If the underlying distribution is NOT normal, then you are interpreting the results incorrectly. In this case, the underlying distribution is not normal. When dealing with the tail, this is a big deal. 1.9% of your sample (i.e. two observations out of 107) have a page count of over 847 pages. If the normal assumption that you are relying on when you invoked the chi-squared test were true, the probability of this happening would be 0.00000032%. Additionally, if ages were normally distributed with the sample variance, the chances of an author being 69 years old is 0.00035%. Yet in the data, 1% of the authors are that old.

And yes, the authors being homogenous is an implicit assumption in your model. If this model provides evidence at the p = 0.0006 level that Joseph Smith was not a 19th Century author, then we have similar evidence that Johann David Wyss and Charles Dickens weren’t 19th Century authors, either. Shouldn’t three extreme outliers in a set of only 106 data points indicate that there is a problem with how you are scoring these extreme outliers?

KR: Based on my experience we’d still be counting the BofM as an outlier even if we tried to use a different distribution.

If we use the actual distribution of the data rather than the normal distribution, the BoM is an outlier at the p = 0.01 level.

But does that really have any bearing? For example, what if our model had three categories of books:

1- Typical 19th Century books that were written to entertain, educate, and persuade.

2- 19th Century books that were written to resemble the Bible.

3- Authentic ancient books.

A book belonging the category 1 isn’t necessarily going to have a page length drawn from the same distribution as a book belonging to category 2. This is what I mean by homogeneity.

Based on page length, we can reject the BoM belonging to category 1 at the p = 0.01 level. The other half of your analysis shows the data are consistent with the BoM belonging to category 2. However, by only comparing the BoM to the Bible, your doesn’t give a good indication how likely it is to belong to category 3. To see how similar the BoM is to ancient books, we would need to compare it to a wide variety of ancient books to determine how well it fits into that set. You just compared it to one book.

All that said, this is a really fascinating analysis and I look forward to your next installment.

Best,

Billy

“Your analysis that came up with that number is flawed (the sample data is not normally distributed).”

And yet, none of the highly credentialed quantitative specialists that’ve looked at this sees that as a fatal flaw. Your highly-trained legal mind (at least I recall that you’re a lawyer–apologies if I’m mistaken) sees a rule violation, and you’ve filed a motion to dismiss. Ours, who are used to seeing the statistical sausage get made, know that this is par for the course, and that these deviations don’t generally invalidate the statistical inference on offer.

“When dealing with the tail, this is a big deal.”

The normal distribution would also posit a tail there, just one that’s shaped a little differently. And not differently enough to dramatically alter our interpretation of the BofM’s data point.

“Shouldn’t three extreme outliers in a set of only 106 data points indicate that there is a problem with how you are scoring these extreme outliers?”

The 106 data points help inform us as to the state of the underlying distribution, and allow us to make some guesses as to what it looks like. Samples like that can often, as is the case when relying on randomness, capture unusual examples that don’t seem to fit the distribution. As you point out, though, outliers are outliers for a reason: Dickens because of his incentive structure, Wyss because of his unusual career path (becoming an author after spending his life as a well-educated pastor, who would’ve written a great deal), and the BofM because of…well, that’s the entire question under consideration.

The incentive structure is a good explanation for Dickens because there’s a clear causal connection between that structure and producing more pages. The structure would do the same for any author, to one degree or another. The ‘producing something like the bible’ explanation, though plausible on its face, lacks that clear causal connection. It certainly didn’t lead the authors of other pseudo-biblical works to write more pages. Why should it have done so with such certainty in Joseph’s case?

“All that said, this is a really fascinating analysis and I look forward to your next installment.”

Thanks Billy. I’ll look forward to continuing our conversation in a few days.

KR: And yet, none of the highly credentialed quantitative specialists that’ve looked at this sees that as a fatal flaw. Your highly-trained legal mind (at least I recall that you’re a lawyer–apologies if I’m mistaken) sees a rule violation, and you’ve filed a motion to dismiss. Ours, who are used to seeing the statistical sausage get made, know that this is par for the course, and that these deviations don’t generally invalidate the statistical inference on offer.

Is that an appeal to authority? In any case I am not an attorney. I am a “highly credentialed quantitative specialist” in my own right. But I’d rather keep this focused on the arguments themselves rather than on the strength of my C.V.

If I may tell a personal story, when I was in graduate school I found it remarkably easy, for example, to do a multivariate linear regression: if you could invert X-transpose-X (i.e. if the matrix X-transpose-X is non-singular), you could solve for a line through k-dimensional space that minimized the sum of squared errors. Using linear algebra, the formula to do this is one of the most elegant things in all of mathematics. That’s remarkable. However, that is the easy part. The hard part is figuring out what, if anything, the regression actually implies. The hard part if understanding the model’s validity.

This goes way past looking at the t-statistics of the betas and has little to do with R-squared. The key things I remember focusing on was whether the explanatory variables were independent and whether the error terms really were independent, identically distributed, and normally distributed. That is when words like autocorrelation, multicollinearity and heteroskedasticity entered my vocabulary. Any of these problems could cause our models and our confidence in them to be significantly misplaced. Anscombe’s Quartet illustrates the significance of this nicely.

It is the responsibility of the person who proposes a model to understand its implicit assumptions, to evaluate how likely they are to be true, to understand the implications, and to make the appropriate caveats.

I understand the pain of making sausage. In my presentations I often lead off with an image from the Simpsons of the Springfield Sausage Factory (it has a banner in front that reads, “Kids, come see how it is made!”) We have to do the best we can with the data we have. I get that. But we also need to understand the theory backing the models so that we can put in the appropriate caveats.

In this case, the Book of Mormon is an outlier. I am not contesting that. The question is whether it is an outlier at the p = 0.01 level or at the p = 0.0006 level. The other issue is the one involving homogeneity: what does a book being an outlier on this set imply? We agree that a serialized novel written by Charles Dickens is not homogenous with other books published in a single volume; we agree that Pickwick Papers being an outlier has no bearing on whether it is really 19th century literature.

The question is whether the Book of Mormon is homogenous with the typical books on this list, or whether it is like the Pickwick Papers and has a mundane explanation for being different. I don’t think it homogenous with the other books, which is why I’m leaving my odds at 1-to-400.

That said, I think this is a fascinating argument and I appreciate you sharing it.

Best,

Billy

“I am a “highly credentialed quantitative specialist” in my own right.”

Greetings fellow highly credentialed quantitative specialist! We who are about to analyze salute you!

“The question is whether it is an outlier at the p = 0.01 level or at the p = 0.0006 level.”

And that’s a fair thing to wonder. Kolmogorov-Smirnow test is significant (p = .015). Skewness is 1.3 and kurtosis is 2.9. So you’re right about the skew, but with that kurtosis, the normal distribution ends up overestimating the tail by quite a bit. Throwing the normal curve on the histogram suggests that’s the case. Happy to email it your way if you’re curious.

Finding the right distribution and trying to fit it is tough with just excel and my neutered SPSS, but, eyeballing it, I could see it being something like a chi-square with about 5 df. If you align the peak of that distribution with the peak of the histogram, that would put 876 pages at somewhere like chi-square = 20, which would be a p of around .001, which would split the difference between the two of us.

But we should really be dealing with this data at the word level instead of the page level, so until that gets fixed trying to fix the distribution is small beans.

“The question is whether the Book of Mormon is homogenous with the typical books on this list, or whether it is like the Pickwick Papers and has a mundane explanation for being different.”

I appreciate you coming at least that far with me–an acknowledgement that there’s something about the length of the BofM that doesn’t fit and that requires explaining. Getting critics even that far on any topic can be a challenge (and I know it can be a challenge on the other side as well). The key is identifying that alternate explanation (i.e., that he was trying to write something like the Bible) and seeing how much water it holds. It feels pretty leaky to me, but apparently your mileage is varying, and that’s fine.

Cheers!

KR: Greetings fellow highly credentialed quantitative specialist! We who are about to analyze salute you!

The pleasure is mine.

KR: And that’s a fair thing to wonder. Kolmogorov-Smirnow test is significant (p = .015). Skewness is 1.3 and kurtosis is 2.9. So you’re right about the skew, but with that kurtosis, the normal distribution ends up overestimating the tail by quite a bit.

I was originally surprised by the Kurtosis number, but when you consider how thin the tail is on the left, it makes more sense. After all, the normal distribution predicts that 5% of books have 11 pages or fewer.

KR: Finding the right distribution and trying to fit it is tough with just excel and my neutered SPSS, but, eyeballing it, I could see it being something like a chi-square with about 5 df. If you align the peak of that distribution with the peak of the histogram, that would put 876 pages at somewhere like chi-square = 20, which would be a p of around .001, which would split the difference between the two of us.

Does a continuous distribution that actually fits the data exist? Not necessarily. My p = 0.01 is based on the Empirical Distribution Function which has the advantage of actually fitting the data.

KR: But we should really be dealing with this data at the word level instead of the page level, so until that gets fixed trying to fix the distribution is small beans.

I’d also be interested in why this was limited to first books. That seems arbitrary. The big thing I want to see is a larger sample with more books.

KR: I appreciate you coming at least that far with me–an acknowledgement that there’s something about the length of the BofM that doesn’t fit and that requires explaining. Getting critics even that far on any topic can be a challenge (and I know it can be a challenge on the other side as well).

You’re welcome 🙂 I appreciate an analysis that has some bearing in actual data.

KR: The key is identifying that alternate explanation (i.e., that he was trying to write something like the Bible) and seeing how much water it holds. It feels pretty leaky to me, but apparently your mileage is varying, and that’s fine.

Even if we can’t identify a specific alternate explanation doesn’t mean that one doesn’t exist. Nor does it mean that that unknown explanation is unlikely. As an example, a few months ago I saw several points of light that were close together in a tight row, quickly moving in the night sky. It was clearly not an airplane and was unlike anything I’d ever seen. Somebody asked me what it was, and I said in jest, “It must be aliens. There is no other explanation.”

Really, there was another explanation and me not knowing what it was didn’t mean it didn’t exist and didn’t have a high probability of being the correct explanation. In this case, the correct explanation turned out to be that it was a set of SpaceX satellites that had just been launched and were in the process of being deployed.

“Does a continuous distribution that actually fits the data exist?”

If it’s discontinuous, then there’s probably a cliff at the 500 page mark, after which it drops off rapidly, which wouldn’t be great news for your tail.

“My p = 0.01 is based on the Empirical Distribution Function which has the advantage of actually fitting the data.”

It’s also has the advantage of being a bit of a cop-out, as I’d need to sample 10,000 more books to have a shot at replicating my original estimate. Maybe Stan’s got a good way to extract the metadata from Nineteenth Century Collections Online.

“Even if we can’t identify a specific alternate explanation doesn’t mean that one doesn’t exist.”

It’s good to know that even critics have a shelf upon which to stick their Zelphs. We’re in the no-shelf zone here! (Or at least everything on it has to be tagged and numbered.)

“I’d also be interested in why this was limited to first books.”

I’ll admit that there was an untested assumption that later works would generally be longer than initial ones, on the premise that authors build up to toward epic masterpieces, and that people who eventually write long, complex narratives generally have to cut their teeth on shorter, simpler ones. Brandon Sanderson is capable of delivering a Rhythm of War (1232 pages), but he first had to get out things like Elantris (492 pages) and Alcatraz verses the Evil Librarians (320 pages). It would be interesting to see if that assumption pans out for 19 century works.

KR: Brandon Sanderson is capable of delivering a Rhythm of War (1232 pages), but he first had to get out things like Elantris (492 pages) and Alcatraz verses the Evil Librarians (320 pages).

Rhythm of War is an interesting example. While it is a hefty book standing alone, it is only one book of a single epic story that will eventually be about 10,000 pages longer than the Book of Mormon. It could be argued that just as the books of the Book of Mormon should collectively count as one book, the books of the Stormlight Archive should count as one book, too.

When people publish shorter books earlier in their careers, is that because they weren’t up to the task of writing longer books without more practice, or is it driven by decisions of publishers who don’t want to risk publishing a more expensive long book on an unpublished author? Or is it driven by starving authors who need a royalty check and don’t have time to write longer books? If Dickens didn’t have the opportunity to publish his first book in a serial fashion, would it have been so long? Is Brandon Sanderson releasing the Stormlight Archive in serial fashion because he doesn’t yet have the experience to write a single book with 11,000 pages?

KR: If it’s discontinuous, then there’s probably a cliff at the 500 page mark, after which it drops off rapidly, which wouldn’t be great news for your tail.

If that’s the case, would it definitively prove that all books longer than 500 pages are really ancient scripture? The truth is there are lots of books the size of the Book of Mormon or longer. Models are not reality, but our models should account for the size of books that actually exist.

KR: It also has the advantage of being a bit of a cop-out, as I’d need to sample 10,000 more books to have a shot at replicating my original estimate.

It isn’t a copout. It is what the data indicates. You don’t need 10,000 or more books to prove your original estimate is valid. You just need a valid sample of data that indicates the right-hand tail is as thin as you seem to think.

Excluding the Book of Mormon, your data shows two very extreme outliers out of only 107 books. This needs to be accounted for. In broad categories the possibilities are:

1- Your assumptions are true and we stumbled upon a string of events that is less likely than winning the mega-lottery.

2- Like Joseph Smith, we have strong evidence that Dickens and Wyss weren’t really 19th Century authors.

3- Your basic model framework is valid, but the real underlying distribution has a long tail and/or is bimodal. This would indicate that these multiple outliers really aren’t that extreme after all.

4- There is some other flaw in the framework.

You can’t make up ad hoc rationalizations for why Pickwick Papers doesn’t fit into your model, but then rigorously insist that the BoM must fit.

KR: It’s good to know that even critics have a shelf upon which to stick their Zelphs. We’re in the no-shelf zone here! (Or at least everything on it has to be tagged and numbered.)

Touche, LOL. Historically, there have been things we don’t scientifically understand which could easily be explained by appeals to religious traditions. For example, consider Evolution. Darwin and his critics knew that evolution would have taken at least hundreds of millions of years to produce the complexity and diversity of life we now have. But according to 19th century science, if the sun was hundreds of millions of years old it would have burnt out by now. Further, if the earth was hundreds of millions of years old, all the land mass would have washed into the sea by now. But evolution predicted that somehow, the sun and earth must be very, very old.

In the 20th century, we figured out that the sun is actually burning nuclear fuel and has been around for billions of years. Likewise, we learned that plate tectonics regenerate landmass and that the earth is billions of years old, too. Evolution was vindicated. Zelf no longer needed that shelf.

Naturalism has a superlatively excellent track record, and betting that its success will continue seems a little bit different than religious faith.

“When people publish shorter books earlier in their careers, is that because they weren’t up to the task of writing longer books without more practice, or is it driven by decisions of publishers who don’t want to risk publishing a more expensive long book on an unpublished author?”

In my experience as an aspiring author, and in knowing quite a few people in this space, it’s generally the former. Authors dream about writing something on the scale of Stormlight, but that’s not where they start. They usually start with short stories, eventually have an idea for a relatively simple, cohesive novel, and then either expand from there (via sequels), or move onto more complex projects.

Paolini’s a good case to consider here. Eragon, his first effort, was pretty long (150k). But it’s only after Eragon became a success that the sequels really build things out (Eldest – 213k; Brisingr – 254k; Inheritance – 280k). That’s not because Eragon started out at 300k and the publisher threw it back (he needed a bit stronger of an editor for Eragon, to be honest). It’s because he was still developing as a writer, and needed confidence and experience to even consider expanding to that kind of scale.

It’s also worth remembering that the Inheritance Cycle was a decade-plus effort. Stormlight, by the end, will probably have taken Brandon 30 years.

“2- Like Joseph Smith, we have strong evidence that Dickens and Wyss weren’t really 19th Century authors.”

This would only apply if they also fit within the distribution of ancient scripture, which they don’t.

That’s part of the beauty and curse of the Bayesian approach. It works a bit like diffusion, pushing beliefs away from theories where the evidence doesn’t fit toward ones where they do. Dickens and Wyss get pushed away from both the idea that they match other 19th century authors and that they’re ancient (which is as it should be), and toward other explanations, as we’ve already discussed. The same isn’t true for the BofM, and soon enough this small note of evidence will be supported by a rather robust chorus.

“Naturalism has a superlatively excellent track record, and betting that its success will continue seems a little bit different than religious faith.”

And that bet (you could call it trust, built on a foundation of past experience), is almost the definition of a very low prior. Since you haven’t taken issue with where I’ve set mine, I’ll assume I’m modeling that bet adequately enough.

KR: This would only apply if they also fit within the distribution of ancient scripture, which they don’t.

Regarding the distribution of ancient scripture, I would think a valid likelihood ratio would be considering the same evidence in the numerator and the denominator, i.e. P(876 Pages|Modern)/P(876 Pages|Ancient).

In other words, find 100 ancient books, calculate the mean and sample variance, assume a normal distribution, etc.

What is your theoretical basis for dinging modern authorship because it has 876 pages but disregarding the total page count altogether for ancient authorship? The point of this is to compare how well the evidence fits under each hypothesis, not cherry pick evidence against modernity and compare it to different cherry picked evidence in favor of antiquity.

I’ve been thinking about the length of the Book of Mormon in the context of nineteenth century literature, and I hope you’ll indulge one more comment.

In 1687, Blaise Pascal wrote, “Je n’ai fait celle-ci plus longue que parce que je n’ai pas eu le loisir de la faire plus courte.” Since then others have made similar remarks. “I have already made this paper too long, for which I must crave pardon, not having now time to make it shorter.” Benjamin Franklin. “Not that the story need be long, but it will take a long while to make it short.” Henry David Threau. “I didn’t have time to write you a short letter, so I wrote you a long one.” Mark Twain.

When viewed as literature, the Book of Mormon has some excellent passages and storylines. However, if it would have been subject to some robust copyediting, it’s aggregate quality could be greatly improved which would have resulted in the overall length of the book becoming more consistent with its peers.

As Mark Twain quipped, “If he had left out [and it came to pass], his Bible would have been only a pamphlet.”

From the perspective of the Bayesian model, is the book being longer than its peers evidence that it’s an actual translation of an ancient text, or is it evidence that it was dictated over a short period of time and not subjected to the revisions it clearly needs?

Too often we ask questions based on a set of assumptions that are too limited. It is quite difficult to assess whether or not the Book of Mormon is a translation without discussing the nature of the translation. Your analysis assumes something about translation that is not based on any evaluation of the text. The nature of the language of the text (and in many cases, the need for editing) show the evidence that it really was dictated. However, once we accept (as all evidence indicates) that it was dictated, we are still left with the question of how or whether that dictation is related to an ancient text or a modern composition. By the way, it is also clear that it is based on a previously composed text. That is evidence, but not yet determinative of the type of previously composed text.

“is the book being longer than its peers evidence that it’s an actual translation of an ancient text, or is it evidence that it was dictated over a short period of time and not subjected to the revisions it clearly needs?”

This is something that an old mission buddy of mine brought up elsewhere, in connection with the idea that the BofM was self-published, and thus not subjected to copy-editing. It’s also an extension of my “amateur” idea in the skeptic’s corner. I agree that it’s an interesting niggle, but I could see it cutting both ways. If you don’t have an editor less is going to be cut, but you also have to pay by the page, which could serve to disincentivize length.

And if we tried to look at a sample of dictated texts…well, I’d have to assume that would result in dramatically shorter texts overall, given the extra effort and manpower involved.

Lots of fun things to think about!

And as Robert helpfully reminded us below, all those instances of “and it came to pass” are actually pretty expected on the whole!

http://premormon.com/resources/r003/003Smith.pdf

Hi Billy,

It has been almost two years since we interacted. I hope you and your loved ones are well.

I had to smile at your comment. For me, this is a brand-new objection/point of view with regard to the Book of Mormon: that it was inadequately edited. 🙂

Really? I am assuming that you are serious. If so, what parts of the Book of Mormon do you suggest should have been left out by the editor? I am genuinely interested.

Best wishes,

Bruce Dale

Hi Bruce,

Under the hypothesis that it is the Book of Mormon is modern, the BoM is an outlier compared to the first books of other 19th Century authors with regards to word count. I’m making the simple observation that if it would have been written and edited with the same standards as its 19th Century peers, it would have been significantly shorter *and* would have taken longer to write.

As a few examples, Alexis de Tocqueville didn’t write, “And thus did the thirty and eighth year pass away, and also the thirty and ninth, and forty and first, and the forty and second, yea, even until forty and nine years had passed away, and also the fifty and first, and the fifty and second; yea, and even until fifty and nine years had passed away…And it came to pass that the seventy and first year passed away, and also the seventy and second year, yea, and in fine, till the seventy and ninth year had passed away; yea, even an hundred years had passed away.”

Jane Austen didn’t increase the page count of Sense and Sensibility by quoting nineteen chapters of the Bible in their entirety.

Charlotte Bronte didn’t write the phrase “and it came to pass” a thousand times.

Best,

Billy

Billy,

Nice idea, but it doesn’t work. There was a very large body of literature of the period imitating the KJV, and “and it came to pass” is clearly modeled on the KJV language and could have been written in another way–but another way wouldn’t have signaled scriptural language to an audience of that time.

I have no idea what kind of evidences are coming in this series, but a close examination of the way “and it came to pass” functions in the text indicates that it has a very specific textual function (as do some other common linking phrases). That strongly suggests that it was not a stylistic addition, but one that had a reason to be there.

As for the fascinating string of empty dates, those also have reason and precedent in an ancient text. They are certainly foreign to our sensibilities, but that is the point. There are several elements of the construction of the text that do not respond to modern concepts. Those, I find, are more interesting that mere length.

Thanks for commenting Brant. I’m very glad to have you reading these, and I’ll be interested in your thoughts.

“Those, I find, are more interesting that mere length.”

I absolutely agree. Looking at length was a bit of a proof of concept for me, and though I think it’s a valid starting point, it’s probably the least compelling aspect of authenticity that comes to mind. There’s much more meat coming down the pike, though my lack of time and specific subject-matter expertise means that the analysis of its ancient characteristics stays at a bird’s eye level. If, at the end, you think there are characteristics that might be amenable to a deeper dive that would be great information to have.

Cheers!

Hi Brant,

My point on this is subtle and specific to the technical aspects of Kyler’s argument. If you will allow me to clarify, he assumes that in regards to number of pages, 19th century literature is homogenous and that page count has normal distribution with a mean of 261 pages and a standard deviation of 152 pages. He says the Book of Mormon has 876 pages, which means it is nearly 6 standard deviations above the mean. Based just on page count, this implies we can be 99.9%+ certain that the Book of Mormon is ancient.

That is the crux of his statistical argument. The point is obfuscated with the Bayesian calculations, Mahalanobis Distance outlier calculations, general analysis that has no bearing on the math, etc. But what I just said is really what’s driving his results. My point is that I disagree with the implied assumption that 19th century literature is homogenous and that page count is normally distributed. Perhaps the wordiness examples I’ve laid out are perfectly consistent with an ancient Book of Mormon. I’m simply stating that modern books (not necessarily the BoM) that “signal scriptural language,” plagiarizes Bible chapters by the dozen, are generally wordy, and are specifically designed to be weightily and comparable to the Bible shouldn’t be expected to have the same number of pages as more typical books.

I am NOT saying that the Book of Mormon is incompatible with ancient Mesoamerican books of scripture. I AM claiming that in and of itself, having lots of pages really isn’t extraordinarily strong evidence that the book is ancient.

Without attempting to divine his intent, length is a more useful argument about Joseph as an author rather than the Book of Mormon as ancient. If Joseph Smith were not seen as a viable author, that opens the door for a historical text. I agree that the logic is two steps removed. I will stay far away from math and statistics. I have no talent for either.

Hi Billy:

As you know, the alternate hypothesis, the one that I accept, is that the Book of Mormon is NOT a modern book. It is an authentic ancient document. According to this hypothesis, therefore, holding the Book of Mormon to “modern” standards of editing and writing is unreasonable and does not follow as a logical argument. But that is the argument you seem to be making.

If you think the Book of Mormon is a modern production, then your objection might be reasonable. But for me, the fact that the Book of Mormon does not read at all like any of the thousands of modern books I have read is a definite piece of evidence in its favor. It does not read at all like Dickens, or H. Rider Haggard, let alone L. Ron Hubbard (yes, I have read all these authors…and a lot more.)

BTW, scripture always quotes other scripture. Note how many times Christ quotes the Old Testament prophets. And Paul quotes Isaiah extensively, as do the books of the Qumran community and the Nag Hammadi manuscripts. So the fact that the Book of Mormon quotes a lot of other scripture, especially Isaiah, is simply another point in its favor, not a point against it…as you seem to believe.

You and I have interacted a lot regarding my article “Joseph Smith: the World’s Greatest Guesser…” https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/joseph-smith-the-worlds-greatest-guesser/

In that article, we cite 131 points of evidence, as reported by Dr. Michael Coe, that link the world described in the Book of Mormon with ancient Mesoamerica. There are actually hundreds of other points of evidence that link the Book of Mormon and ancient Mesoamerica that we did not include in our article.

We did not include these other points because Dr. Coe did not mention them in his various editions of The Maya, and we were focused on showing that his claim that “99% of the details in the Book of Mormon are false” was completely off base. If we can trust Coe’s mastery of the details of the world ancient Mesoamerica, then the Book of Mormon describes a world very much like that world.

One of these additional points of evidence is the use of the phrase “and it came to pass” in the Book of Mormon, which seems to offend your editorial sensibilities. 🙂 I do not have enough remaining characters to respond to this point in this comment, so I will post a second comment to deal with it.

Best wishes,

Bruce Dale

BD: As you know, the alternate hypothesis, the one that I accept, is that the Book of Mormon is NOT a modern book. It is an authentic ancient document. According to this hypothesis, therefore, holding the Book of Mormon to “modern” standards of editing and writing is unreasonable and does not follow as a logical argument. But that is the argument you seem to be making. If you think the Book of Mormon is a modern production, then your objection might be reasonable….

Hi Bruce,

What you need to remember is that Bayesian analysis really doesn’t have anything to do with how “specific, detailed, and unusual” a prospective correspondence is. Rather, it has to do with looking at the evidence from different paradigms. As you said in your paper, “[the Bayesian likelihood ratio] is the probability of the evidence assuming that the hypothesis is true divided by the probability of the evidence assuming that the hypothesis is false.”

To do this correctly, it doesn’t matter whether or not you or I personally believe hypothesis A or B. Rather, we need to step into each hypothesis and evaluate the likelihood of the evidence from that perspective.

The reasonableness of my objection has absolutely no bearing on whether I personally think the BoM is modern. All I was doing was evaluating the evidence assuming the hypothesis was true.

BD: So the fact that the Book of Mormon quotes a lot of other scripture, especially Isaiah, is simply another point in its favor, not a point against it…as you seem to believe….

My point wasn’t that excessively quoting scripture is evidence against the the BoM. My point is that *assuming it is modern*, excessively quoting the Bible helps explain the long page length and indicates it is not homogenous with other 19th Century books.

Whether the details of this are consistent with the hypothesis that it is ancient is another issue I did not address.

(The specifics of the quotes are very problematic for the ancient hypothesis, but that is a discussion for another day.)

Hi Billy:

With respect to your most recent interactions with me, you are both correct and incorrect.

First the correct part: I wrote that piece on the number of instances of “it came to pass” in the Book of Mormon for another purpose over six years ago. Either I made a mistake in my search then or the search engines are better now, because a search for the phrase now returns over 1400 instances in the Book of Mormon. Mea culpa for not checking.

By the way, you can search all of the scriptures and other church library materials without being a member or even opening an account by using this link:

https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/scriptures?lang=eng

However, my point with respect to Mark Twain remains correct. If all of those instances of “and it came to pass” had been eliminated by the editor, the Book of Mormon, 531 pages long now, would still have about 520 pages, definitely not a pamphlet. Not a great triumph for the editor.

I am still unclear about why you think the editing job on the Book of Mormon is inadequate. Could you please respond to that point?

On the other issue, strength of evidence in Bayes, you are incorrect.

As Kyler is showing us, different points of evidence, negative or positive, can affect the skeptical prior by different amounts, depending on the strength of the evidence. Kyler is rolling out this analysis using orders of magnitude, i.e., a log scale to evaluate the strength of evidence and how each set of new evidence affects his prior.

In the same way, in our “Greatest Guesser…” article we used three different strengths of evidence as summarized in this paper by Kass and Raftery from the literature (J. of the American Statistical Association, many thousands of citations).

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2291091