Intro/FAQ ⎜ Episode 1 ⎜ Episode 2 ⎜ Episode 3 ⎜ Episode 4 ⎜ Episode 5 ⎜ Episode 6 ⎜ Episode 7 ⎜ Episode 8 ⎜ Episode 9 ⎜ Episode 10 ⎜ Episode 11 ⎜ Episode 12 ⎜ Episode 13 ⎜ Episode 14 ⎜ Episode 15 ⎜ Episode 16 ⎜ Episode 17 ⎜ Episode 18 ⎜ Episode 19 ⎜ Episode 20 ⎜ Episode 21 ⎜ Episode 22 ⎜ Episode 23

[Editor’s Note: This is the fourth in a series of 23 essays summarizing and evaluating Book of Mormon-related evidence from a Bayesian statistical perspective. See the FAQ at the end of the introductory episode for details on methodology.]

The TLDR

It seems unlikely that the colonization of the American continent described in the Book of Mormon would’ve left no genetic evidence in modern (or ancient) Indigenous populations.

Critics of the Book of Mormon can be relied on to bring up the subject of DNA, even though most on both sides have little expertise with which to grapple with the argument. Faithful geneticists insist that we wouldn’t necessarily expect Lehi’s DNA to be detectable in the modern day. From what I can tell, they’re not wrong. Geneticists can do some amazing detective work using the techniques at their disposal, but their tools just aren’t exact enough to draw firm conclusions about Lehi’s story. In the absence of more concrete data, I argue that the probability that Lehi’s colonization would leave no genetic trace should be at least p = .00125, if not higher—not a massive chance, but far from impossible. Even when weighting the scale in favor of the critics, the evidence doesn’t have much of an impact on the authenticity of the Book of Mormon.

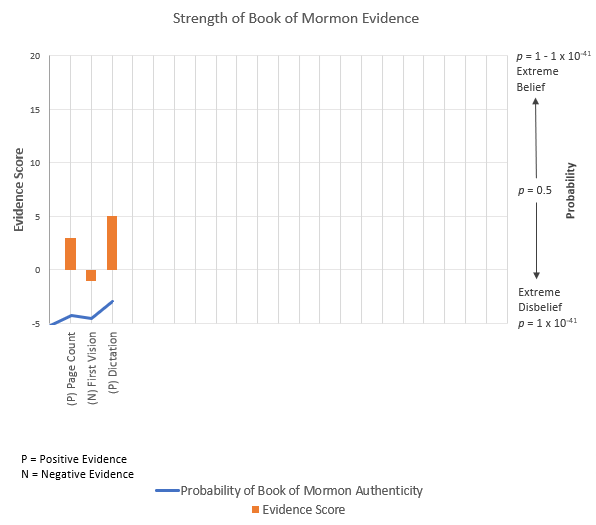

Evidence Score = -3 (reducing the probability of an authentic Book of Mormon by, at most, three orders of magnitude)

The Narrative

When we last left you, our ardent nineteenth-century skeptic, you had been thoroughly intrigued by the story of the dictation of the Book of Mormon. You find the tale incredible, but also oddly compelling, not least of all because of the conviction in the eyes of the young man who told it. As he finishes, the young man once again turns to the fire, where the embers are now breathing their last smokey gasps. You try to find a response, but your mind remains empty, and both of you sit immersed in silence. After a long few moments, the young man stands from the stool, the boards below him creaking heavily.

“Well, I suppose I’m warm enough now to make the walk back to town,” he says, his arms stretching to the ceiling of the cabin. “I’m grateful for your hospitality, and for your truly thought-provoking questions. But it’s time I take my leave.”

You stand as well, holding the book he has given you tightly in both hands. “No trouble at all,” you say. “I’ll wish you godspeed. And I’ll certainly buy your book, for curiosity’s sake.” You reach into your pocket and pull out two dollars. “Though I’m afraid I won’t have use for any preaching you intend to deliver alongside it.”

The young man smiles, eyeing the bills in your hand, but waves it away. “You keep your money. I’ll be back in town in a few days’ time. If you read the book from cover to cover and still have no use for my preaching, the book will be yours as a gift from me.” He extends his hand, and you offer him your own. His grip is strong and sincere. “But I have a feeling you’ll be paying for the book, and you’ll be gaining the kingdom of God in return.”

Your eyes turn toward the Bible that still lay open and dusty on the table—the symbol of a once-firm belief that you now knew to be inexorably out of reach. This young man could believe whatever he wished, but those beliefs would never be yours. “Then I will thank you in advance for a book freely given.”

The grip tightens slightly, but he just shrugs. “If it was up to me to persuade you otherwise, you would be right. But I will say this: That book has the power to consume you, as it did me. You will feel the spirit of God confirming for you the truth of what you read. You will come to know that the native inhabitants of this land are truly of the house of Israel.”

The grip releases. The young man leaves. The door shuts. But your mind stays firmly on his final words. What was he trying to say? That the Indians even then living on the frontier were, what? Hebrews? That seemed a bold claim. It wasn’t a new claim, of course. But every person you had heard making that claim had just seemed so ridiculous. Their arguments had been raw speculation, nothing more. From what you could tell, Israel bore no connection to anything in native America, be it cultural or biological.

Could this book somehow prove otherwise? You find it hard to believe so. You lay the book down on the table next to the dusty Bible. You, yourself, have little expertise to say for sure, but if even the Greeks believed that lineage could be passed down through biological mechanism, then surely, someday, we could trace the lineage of the native peoples of the Americas. And if Israelite lineage could not be found? Then it would seem unlikely that any kind of Hebrew colonization could have such little impact on the heritage of the American Indian.

The Introduction

This thought isn’t one that would’ve entered the mind of anyone in the nineteenth century. But it’s one whose stage was set when the 1981 edition of the Book of Mormon claimed that Lehi and his posterity were the principal ancestors of the American Indians. If the inhabitants of the American continent are descended from Israelites, then it seems obvious that Israelites should be genetically related to America’s Indigenous peoples. More importantly, the absence of any trace of genetic relatedness should be proof positive that the Book of Mormon is a fraud.

That line of thinking should immediately set off at least one red flag. We’re all likely familiar with a certain logical maxim that “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.” And while that’s true to a certain extent, it’s not necessarily true in a Bayesian context. In this I stand in the company of atheist and historian Richard Carrier, who argues this point forcefully—the lack of evidence of a given historical event may not prove that event didn’t happen, but it does make that event less likely, particularly if we have good reason to expect that evidence to be there if the event were real.

The question then, for us, is how much should we expect Lehi’s DNA to be detectable in the present day? If Lehi should have left a genetic trace, given what we know from the Book of Mormon, then the lack of that trace should make the faithful reconsider its authenticity. On the other hand, if it’s likely that Lehi’s DNA would have been lost, then failing to detect it shouldn’t sway anyone’s opinion one way or another.

The Analysis

The Evidence

The evidence in this case is something on which both critics and the faithful tend to agree: No genetic analysis of any kind has found evidence that Indigenous populations in North or South America can trace their ancestry to the Middle East at the time of Lehi. Indigenous peoples of the American continent are overwhelmingly descended from Asian ancestors crossing the Bering strait (though debate continues regarding the date of those migrations and the number of waves involved). Extant theories posit incursions from a host of other populations, whether Japanese or Egyptian or Phoenician or Polynesian, but so far none of them have held firm water, and none of them point to the Israel of 600 BC.

Some see a potential exception to this in the discovery of the X2a haplotype in mitochondrial DNA of Indigenous people with ancestry in the heartland of the United States. That particular haplotype is also found in relatively high frequencies among Middle-Eastern populations. The well-identified problem with this possible exception is that the DNA is too old—dating methods that track mutations in DNA over time place the origin of that DNA at around 11,000 BC, meaning that DNA most likely originated with someone from the Middle East who migrated to the Americas at the end of the last ice age—not from Lehi.

So, in what ways can we account for this lack of evidence?

The Hypotheses

Lehi’s genetic contribution is real, but not currently detectable. According to this theory, there was a Lehi, and he and those who journeyed with him are among the ancestors of the Indigenous peoples of the American continent. To understand what this theory claims, we need to know what the Book of Mormon itself has to say about Lehi’s migration and, unlike the genetic evidence itself, this bit is somewhat controversial. Critics who employ DNA evidence generally rely on a popular misconception—that the Book of Mormon and church leaders teach that Lehi and his family (along with Mulek and those who accompanied him) colonized an otherwise empty American continent, which would mean that all Indigenous inhabitants could trace their ancestry entirely to Middle-Eastern sources.

But the Book of Mormon doesn’t actually say that. It, in fact, implies that there were other people already there when they arrived and that those people continued to interact and interfere with Nephite society. The speculated preconceptions of church members, whether in the nineteenth century or today, do not bind the Book of Mormon to theories that are clearly false. If Lehi did arrive on the American continent in 600 BC, his family would’ve been only one of hundreds of thousands, and his party of 40 or so would have been quickly absorbed into the local populations they encountered. Under these circumstances, any Middle-Eastern genetic contribution (if Lehi’s DNA did indeed resemble that generally found in the Middle East) could have conceivably faded over time or even disappeared entirely, subject to the well-documented phenomena of genetic drift and population bottlenecks. Even if that DNA had survived in trace amounts, much of it would be difficult to distinguish from more modern incursions of European or Middle-Eastern immigrants to the Americas.

Lehi is a fabrication of Joseph Smith, and thus could not have contributed genetic material to modern Indigenous populations. In short, the reason DNA evidence for the Book of Mormon does not exist would be because the characters and events described in it are fictional. We would no more expect to find Middle-Eastern DNA in the Americas than expect to find Hobbit DNA in Wales.

Prior Probabilities

PH—Prior Probability of Ancient Authorship—As is my custom, I’ll use the posterior probability from our last analysis as our base estimate of the probability of an authentic Book of Mormon (and thus, an authentic Lehi to contribute DNA). Our skeptic, though technically somewhat less skeptical, is still rather dogmatic, placing that probability at p = 9.96 x 10-35. Here’s a look at the evidence we’ve considered thus far.

CH—Prior Probability of Modern Authorship—As the only alternative to a real Lehi is a fake one, we can calculate the prior probability of a fabricated Lehi as 1 – 9.96 x 10-35.

Consequent Probabilities

CH—Consequent Probability of Ancient Authorship—Given the information we have in the Book of Mormon, how likely would it be for Lehi’s genetic legacy to be lost to time? Well, we know from the outset that it isn’t impossible, because the same thing has already happened in a number of other instances, from the Vikings of Newfoundland, to the African commanders of the Roman army in Britain, to the Philistines in Palestine. The Philistines are a particularly instructive case, given their extensive, storied, and well-documented history in the region. Enough Philistines migrated from elsewhere in the Mediterranean to be able to field armies against the Egyptians, but no genetic trace of them remains in the modern population. And the Vikings? They sent a few dozen colonists to the Americas who interacted with local Indigenous tribes. Where’s their genetic legacy? It doesn’t exist. We have to rely on careful archaeology and well-preserved historical records to know they were there at all. So already we can already see some light at the end of the genetic tunnel.

But the lack of Viking DNA doesn’t give us much to work with for calculating probabilities. Anecdote is not data, and Vinland is little more than a striking, red-bearded anecdote. To get to the bottom of this (or as near as my limited expertise will carry us), we need to take a look at what sort of mechanisms could’ve carried Middle-Eastern DNA from Lehi down to the present. Thankfully, there are only three that we need to be concerned about, and two of them work in functionally identical ways: 1) autosomal DNA, and 2) two sex-linked propagation mechanisms—mitochondrial DNA, which is transmitted only by and to women (or mtDNA for short), and Y-chromosomal DNA, which is carried by and transmitted through patriarchal lines.

Autosomal DNA. For humans, autosomal DNA refers to the 22 non-sex-linked chromosomes that form the majority of our genome. These chromosomes form through what’s essentially a random mixing process from the original chromosomes of both biological parents. As a result, any given child will have 50% of their autosomal DNA from their mother and 50% from their father, with 25% coming in turn from each grandparent, 12.5% from each great-grandparent, and so on through the generations. This process means that autosomal DNA is pretty useful for determining how two different people are related, and if we happen to know enough about where people’s ancestors hail from, we can use autosomal DNA to build fairly reliable genetic profiles linked to different ethnicities. This is generally the type of DNA that places like Ancestry.com will use to tell you that you’re 1/256th Native American, for example.

The problem with autosomal DNA is that it doesn’t take too many generations for a single person’s genetic contribution to become extremely diluted, if not to vanish altogether. For instance, if you go back 10 generations in your family tree, you’d have up to 1024 people contributing their genetic material, and only material from around 12% of those people would still be detectable in your particular genome. If we go back 14 generations, the probability of being able to match you and your twelfth-great-grandmother using autosomal DNA would be 1.46%—extrapolating from that same data, the odds of being able to match Lehi’s DNA to a hypothetical modern genetic descendant would be about 1 in 1020.

But that limitation doesn’t stop geneticists from being able to do some pretty crazy things using autosomal DNA. They can actually use that inexorable dilution to their advantage—the more dilute a person’s genetic contribution gets, the more it essentially gets chopped up into smaller and smaller pieces as it gets distributed in their descendant’s genetic material. Geneticists can measure the size of those pieces to estimate how far back certain populations began mixing. They can get fairly accurate timings for, say, Mongol incursions into Eastern Europe, or contact between Morocco and sub-Saharan Africa, or, most relevantly, European invasions into Mexico. Some critics have been bold enough to use that evidence as a silver bullet against the Book of Mormon, interpreting the evidence to state definitively that the earliest time anyone from Europe (or, by extension, the Middle East) could have mixed with Indigenous populations in the Americas is post-Columbus, completely ruling out the existence of Lehi.

But to make that claim is to ignore the real limitations of that kind of analysis. Yes, it’s possible to detect genetic material from migrations taking place dozens of generations ago, but it gets progressively harder to do so 1) the farther back you go, and 2) the smaller the contribution relative to other sources. In case you’ve forgotten, Lehi’s situation fits both those limitations pretty snugly, given that he would’ve arrived in the Americas at least 80 generations back, and would’ve been mixing his small party’s chromosomes in with millions of competing genes of Asiatic origin.

The study I cited above gives us some handy figures to work with. They used simulated data to calculate the statistical power for being able to detect a real migration if it occurred. For simulations with admixture ranging from 7-160 generations back, and from 3-50% genetic contribution, they had a power of 94%, meaning their analysis missed 6% of the real migrations in the simulated data. To put those numbers in perspective, let’s consider the Phoenicians. You know, the famed seafarers who colonized dozens of sites across the Mediterranean over centuries. They only contribute about 6% of DNA for people living in those sites today.

So again, keep in mind that the power to detect a migration like Lehi’s would’ve likely been quite a bit lower than 94%. But we’re going to practice a little a fortiori reasoning and just assume that the probability of missing Lehi’s autosomal DNA contributions is quite low (though not by any means improbable), at p = .06.

Sex-Linked DNA. Methods for tracking mtDNA or Y-chromosome DNA are the ying to the autosomal yang. In contrast to a random mixing process, mitochondrial DNA and Y-chromosomes are essentially copied and pasted from parent to sex-linked child, making it possible for DNA to be transmitted indefinitely over thousands or even hundreds of thousands of years. As with autosomal DNA, identifying the frequency of certain genetic markers allows for the creation of ethnicity- and region-based profiles. Well-understood mutation rates help geneticists provide migration timings and help track human movement all the way back to human origins.

But a lot has to happen for this type of DNA to survive from generation to generation. First and foremost, you have to survive to child-bearing age. Then you need to have sex, conceive, and survive the process of having children. Some of those children need to be of your same sex, and those children must similarly survive to child-bearing age. As you might guess, this is by no means a guarantee, particularly in societies with high infant and juvenile mortality, limited household sizes, and constant warfare.

This is where stuff like genetic drift and population bottlenecks come into play. If you’re starting off with a limited population and a lot of genetic competition, it’s not at all uncommon for sex-linked genes to disappear within a few generations. Sometimes a woman has a family with all boys, which alone will stop her mtDNA contribution in its tracks. Sometimes a natural disaster or a mass genocide decimates the population, severely reducing the likelihood that sex-linked DNA gets passed on. A lot has to go right for the genetic chain to remain unbroken, and it doesn’t take many weak links to snap it irreparably.

When people like Dr. Perego cite these issues in defense of the Book of Mormon, they’re absolutely on base in terms of theory, but it’s tough to get a good sense of the kind of odds that would’ve been stacked against Lehi and company’s sex-linked DNA. It would be nice if some well-credentialled geneticist had modelled these sorts of processes specifically for the likelihood of the loss of mitochondrial or y-chromosomal DNA due to genetic drift (let alone for Lehi’s case), but if they have, I haven’t seen it. I even made an attempt at trying to model those processes myself, and learned a few things along the way (see the Appendix for details). But those efforts don’t get us much closer to a firm probability estimate in the case of the Book of Mormon.

That doesn’t mean we’re entirely up a creek. We have, in fact, a few different paddles with which to try to row upstream. The first thing we can do is use the opinions of the experts. When faithful scholars, neutral third parties, and even critics all acknowledge that it’s possible for sex-linked DNA to have been lost, then that suggests that we’re not talking about a 1 in a million long-shot, and that in fact such a thing is quite plausible. Second, we can look at past history for examples of similar things actually occurring. As we’ve already discussed, we do, indeed, have examples of real migrations for which no sex-linked DNA can be found. Together, these two things suggest that the loss of sex-linked DNA is not unexpected in principle.

The real issue, though, is whether we should expect it in fact. And that’s the third thing we can do—look at the circumstances described in the Book of Mormon and see if they align with the kind of circumstances where we’d expect genetic drift. And from where I stand there are three important characteristics of such circumstances that we’d need to consider. The first is the presence of population bottlenecks, and the Book of Mormon happens to have those in spades. We have three dramatic bottlenecks in the form of the natural disasters recounted in Third Nephi, the Nephites’ final destruction at Cumorah, and the decimation of Indigenous populations with the arrival of Europeans, as well as more minor instances of famine and warfare scattered throughout the text.

But the other two characteristics are a bit more problematic for the Book of Mormon. As I learned in attempting to simulate these processes, fertility and population growth are key—if women are having somewhere on the order of 6 to 8 births on average over the course of their fertile years, then I don’t think even high mortality rates and horrendous bottleneck events would be enough to stamp their sex-linked genes into oblivion, especially if they have hundreds of years of unchecked growth and prosperity. The Book of Mormon, if taken at face value, heavily implies this sort of strong growth, and this growth would not have been unusual in that area of Mesoamerica.

Lastly, what you need is for Lehi’s founding party to have mixed with the local population, as you would have needed some other genetic lineage to override any sex-linked DNA linked to the Old World. We’ve already discussed this somewhat already when detailing our hypotheses—that sort of mixing is pretty easy to assume for the Mulekites, whose origins are far less detailed and who would’ve landed in a heavily populated area. The Lamanites, whose skin is heavily implied to change color in less than a generation, are likely to have mixed with the locals as well. But Nephi, who takes himself and his small group off into the wilderness and who specifically shun fraternization with their Lamanite neighbors (though specifically having to tell people not to could be an indication that it was happening anyway), is a more difficult case.

If Nephi and his party did, indeed, join together with local tribes (which by the way, wouldn’t have been all that unusual in the context of history), it would actually solve both of these problems—not only would you have the required mixing, but you would also no longer have to assume strong population growth, at least for the first few centuries after Lehi. Nephi’s group, struggling to gain a foothold in the New World, might have seen the same sluggish initial growth as many other fledgling colonies. This, combined with the bottleneck of endemic warfare and the genetic influence of the native inhabitants, could have been enough to put a quick end to their sex-linked DNA. But such a solution would need to be read into the text (though Blake Ostler and Greg Smith see evidence of it there already).

That potentially unusual reading, combined with our commitment to a fortiori reasoning, means that we’re going to need to handicap the Book of Mormon somewhat. And our guide for doing so will be this article from the Dales—father and son engineers who have also made attempts at a Bayesian analysis of the Book of Mormon relative to Mesoamerican discoveries. They suggest that probabilities can be applied to evidence in a more general sense through more qualitative judgments of how specific, detailed, and unusual that evidence is. They themselves, in a relatively brief analysis of the DNA evidence, give a relatively high consequent probability of p = 0.5. Based on our discussion above, we’ll need to be a bit more conservative. What we’re looking for is very specific (sex-linked DNA in modern populations and ancient remains), there’s enough detail in the Book of Mormon narrative to give us a sense of what to expect, and those details suggest that not finding sex-linked DNA would be unusual. Not a “there’s no way this could’ve happened” unusual, but if we’re giving the critics the benefit of the doubt, it’s unusual enough to deserve the probability that the Dales assign to their strongest evidence—a value of p = .02. In this case that estimate gets to receive my patented red labeling, as it’s based much more on (conservative, informed) conjecture than on any hard data.

We’re also going to be kind to the critics by ignoring a separate but important fact—namely, that geneticists can’t tell the Middle-Eastern sex-linked DNA of 600 BC from the European DNA of the modern day (since it hasn’t had time to mutate enough to tell them apart), particularly at low frequencies. Even if geneticists did find Lehi’s sex-linked DNA, odds are good that it would be passed off as an anomaly, or as being modern in origin.

Summary. Now we’re ready to estimate the probability of lacking evidence of Lehi’s DNA, even with an authentic Book of Mormon. Lehi and his party would’ve essentially had three independent shots at providing evidence of his genetic legacy: one for autosomal DNA, one for female-linked mtDNA, and one for male-link Y-chromosome DNA. However, because of the way we’ve constructed our estimate for the sex-linked DNA, we have only one number that covers both. We can thus multiply the probability of missing the autosomal DNA evidence (.06) by our estimated probability of both sex-linked DNA types not surviving (.02), leaving us with a probability of p = .0012.

CA—Consequent Probability of Modern Authorship—This probability is thankfully pretty straightforward. The lack of Middle-Eastern DNA is perfectly compatible with the idea of a fabricated Lehi and Joseph Smith as the author of the Book of Mormon. I’m comfortable assigning this consequent probability a p = 1.

Posterior Probability

With that done, we can move on to Bayes’ formula:

PH = Prior Probability of the Hypothesis (our guess at how likely it would be for Lehi to be a real person, based on what we know so far, which at this point is p = 9.96 x 10-35)

CH = Consequent Probability of the Hypothesis (our estimate of the probability of observing a lack of DNA evidence for the Book of Mormon, given what the Book of Mormon says, or p = .0012)

PA = Prior Probability of the Alternate Hypothesis (our assumption that Lehi was unlikely to be a real person, p = 1 – 9.96 x 10-35)

CA = Consequent Probability of the Alternate Hypothesis (how likely it is that we would end up with no DNA evidence of a 6th century BC Middle-Eastern incursion if Lehi didn’t exist, which for our purposes is p = 1.)

PostProb = Posterior Probability (our new estimate of the probability of an authentic Book of Mormon)

| PH = 9.96 x 10-35 | |

| PostProb = | PH * CH |

| (PH * CH) + (PA * CA) | |

| PostProb = | 9.96 x 10-35 * .0012 |

| (9.96 x 10-35 * .0012) + ((1 – 9.96 x 10-35 * 1) | |

| PostProb = | 1.2 x 10-37 |

Lmag = Likelihood Magnitude (an estimate of the number of orders of magnitude that the probability will shift, due to the evidence)

Lmag = log10(CH/CA)

Lmag = log10(.0012/1)

Lmag = log10(.0012)

Lmag = -3

Conclusion

There are a few reasons that critics like to bang on the DNA drum whenever they get a chance to parade against the Book of Mormon. The scientific air that surrounds it and the real expertise that powers it makes genetics a formidable and persuasive weapon. But people like Dr. Perego aren’t wrong when they insist that it’s not a silver bullet, and that the evidence isn’t as airtight as the critics might like. Based on what I’ve covered here, the argument for the Book of Mormon did lose three orders of magnitude. This may seem competitive in the context of the evidence we’ve considered thus far. Those with that impression, though, might want to exercise just a little bit of patience. That context is going to begin to expand very soon.

Skeptic’s Corner

What those who care about this evidence are in dire need of at this point is a solid, nuanced, expertise-driven simulation study looking at how likely it would be for Lehi’s party to fall off the genetic map. Doing that sort of thing would take a lot of time, expertise in both genetics and ancient population demography, and, potentially, a lot of computing power. I, regretfully, have none of those things.

I’m also concerned about having potentially missed additional population studies involving autosomal DNA. I could only locate the one study, but enough studies with a high enough cumulative sample size of unique individuals would increase statistical power enough that even Lehi’s sparse DNA would start running out of places to hide. At that point there would still be plenty of fallback positions for the faithful perspective, but the statistical argument for this evidence could get quite a bit stronger. Additional technology and improved methodology could have a similar effect. Of course, then again, they just might eventually uncover a certain minor incursion of Middle-Eastern origin into southern Mexico (which wouldn’t be an unreasonable thing to discover, given recent findings), in which case more than a few critics would be obliged to eat their genetic hats.

Next Time, in Episode 5:

In the next episode, we’ll examine the witnesses to the Book of Mormon and discuss the probability that they would stick to Joseph’s story even after they turned against him.

Questions, ideas, and cutting remarks can be sliced in the direction of BayesianBoM@gmail.com.

Appendix

Most of my analysis time for this episode went into building a relatively simple simulation in Python, in an attempt to get a sense of how the magnitude of Lehi’s genetic contribution changed under certain conditions. It, in the end, didn’t provide much clarity, and I didn’t want it muddying the waters of the main analysis. But hopefully those brave enough to wade through this appendix can benefit from my having dug around in the mud.

There were quite a few parameters that had to be estimated to build the simulation (e.g., mortality rates, bottleneck survival rates, fertility rates) and you could make arguments for setting those parameters any number of ways. We could, for instance, use this article to estimate the likelihood of someone in ancient Mesoamerica surviving to child-bearing age (age 15; with the highest estimate being 51.6%). We could then use this article, which estimates that women in ancient Mesoamerica bore a rather astounding 8.14 children on average (with only about four of them surviving).

But those mortality and fertility rate estimates are probably a bit too rosy—they come from examining burials in relatively prosperous urban environments, and don’t capture those who died on lonely Mayan battlefields. They also probably describe births to women who live through the entire period of their fertility, rather than those who die earlier on.

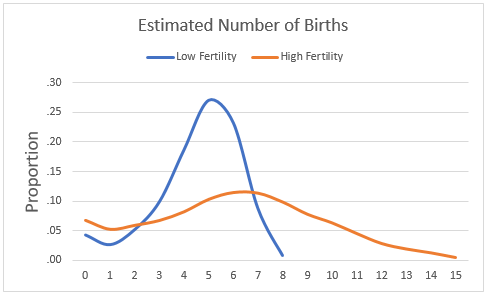

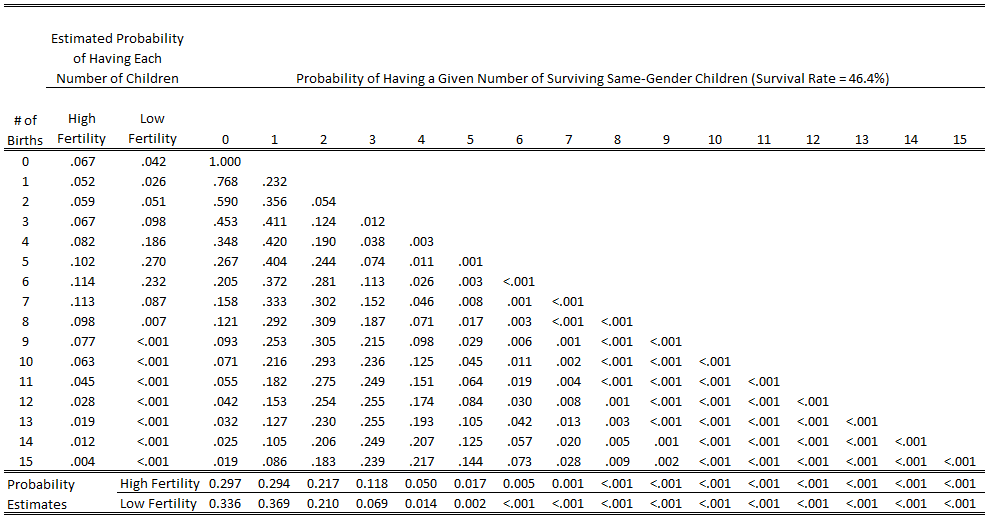

The Book of Mormon also allows us to make some more direct estimates about fertility, as this article does in useful fashion. For at least some periods of the history described, we can assume that growth rates were as high as 1.25%, which given a 30-year average lifespan would put average lifetime fertility at 6. Assuming a 33-year generation length (with average lifespans that low, it should probably be more like 25, but we’ll stick with it for now), that ends up implying a survival rate of 46.4% rather than 51.6%. We’ll use those values for our estimate, and then use this study from India to give us a sense of the shape of the distribution for the overall number of births.

We’ll call this our “high fertility” estimate, because that too is probably a bit on the high side. Average fertility over time was much lower in much of the ancient world, so we could easily expect much lower fertility rates in a number of circumstances. So we can build a “low fertility” estimate too, with, say, 4.5 average births. Together, the distributions for those two estimates could look like this:

These distributions are important, because the probability of having a sex-linked gene survive is (obviously) different depending on the number of children you have. To figure that out, first you have to calculate the probability of a having a given number of same gender children, for each potential number of children that a person might have, and then to have a certain number survive. Here’s how I did it:

- Figure out the number of probability permutations for given combinations of children and the number of children that are a certain gender—this means figuring out how many different ways there are for you, say, to have 5 kids, and only 1 of them end up as a girl. In that case, there’s five permutations—each of the five children could end up being a girl, while all the rest would be boys. The way to do this is through a mathematical procedure called binomial coefficients. If you’d rather not read your way through the serious math, though, here’s a relatively straightforward method for performing the calculations:

- For combinations where all the children are of the same gender, the number of permutations is 1.

- For having 1 same-gender child, the number of permutations is the number of total children.

- For having 2 same-gender children, the number of permutations equals the number of total children minus 1, multiplied by half the total number of children (e.g., for 4 total children, it’s (4 – 1)*(4/2) = 6—this is the same as summing all the values from 1 to N – 1).

- For all other combinations, where X is the total number of children, Y is the number that are a certain gender, and P(X,Y) is the number of permutations for a given combination: P(X,Y) = P(X-1,Y) + P(X-1,Y-1). This is the same as summing all the permutations for each combination of permutations from X = 1 to X = (X-1) for Y – 1.

- For combinations where all the children are of the same gender, the number of permutations is 1.

- For each combination of total children and same-gender children, figure out the probability that you have a certain number of same gender children survive. If X is the total number of children, Y is the number that are a certain gender and, P is the number of probability permutations, and Z is the survival rate, you can calculate that with this formula: P*((Z*0.5)Y*(1-(Z*0.5))(X-Y)).

The result is what you see in the columns in the table below, which you can see alongside the distributions of the number of births in our high and low fertility estimates:

Then you have to do a couple other mathy things for difficult-to-explain reasons: 1) multiply each value in those columns by the respective probability that a person will have that number of children to start with (which gives the probability that someone will have both a given number of children AND a given number of surviving children with their gene), then 2) sum the resulting values in each column (which gives the overall probability of having a certain number of surviving children with that gene). In this case, you can see those values for the high and low probability estimate in the bottom rows of the table above.

Note that the probability of having zero same gender children survive is relatively high in the low fertility scenario, while relatively low in the high fertility scenario. That, right there, is a numerical expression of genetic drift.

I also had to consider the possibility of population bottlenecks. There are a few specific ones that could apply in the Book of Mormon, particularly the destruction in Third Nephi and the final war of extinction ending at Cumorah in 430 AD. With destruction that severe, a mortality rate during the bottleneck of 75% seems to be a decent minimum estimate. We can also include the well-known bottleneck of small-pox and other European diseases destroying up to 90% of the indigenous population. With 33 years to an average generation, that would put the Third Nephi destruction approximately 20 generations after Lehi’s landing, Cumorah at about 32 generations, and the start of the Columnbian exchange at 48 generations, with the present day being close to 80 generations since Lehi. Applying a 75%/90% survival rate on top of our other factors for those specific generations can serve to model the effects of those bottlenecks.

With that, I could build the simulation, which was designed to test how well one of the sex-linked genes would survive over time (which means the result would have to be squared to estimate the odds of neither sex-linked gene surviving). I assumed a starting population of 50 people of a particular gender who had the same type of sex-linked gene (which would fit a maximum estimate of the women in Lehi’s party, plus some random Phoenicians thrown in along with Mulek), and then gave each of those people a chance to pass on their genes. I rolled a random integer from 1 to 1000, and partitioned those numbers according to the proportions associated with each possible option for passing on genes. If they didn’t pass on their genes, the number of people in the next generation with that gene would be reduced by one. If they passed it on enough times to replace their own gene (i.e., once), it would stay the same. Any further same gender children they had would increase the number of genes by that amount minus 1. I then iterated that over 80 generations, in a process similar to a Markov Chain. I also increased the probability of not passing on a gene to 75%/90% for generations with population bottlenecks. I then kept track of if and when the number of people with that gene reduced to 0, as well as the number of people with that gene after 80 generations.

With the high-fertility scenario, growth at about 1.25% per year led very quickly to hundreds of thousands of surviving sex-linked genes by the time the first bottleneck hit. I could only let my computer sit and run it through about 40 generations before each generation started taking too long to process, and by then the number of genes was in the tens of millions.

With the low-fertility scenario, after over 1,000 runs of gene transmission over 80 generations, 35.3% of the time not a single gene was left at the end of those 80 generations, and in cases where there were any left at all there was a maximum of 288 genes. The genes lasted on average through 72 generations, right about the time of the American Revolution. Under such conditions it would be entirely plausible for Lehi’s sex-linked DNA to have been lost to time, and that if it did stick around, it could still be quite rare.

These results tell me a couple important things:

- Neither of these is what really would’ve happened, because sustained high fertility would’ve meant that hundreds of millions of Indigenous people would have been there when Columbus arrived, while sustained low fertility would’ve soon left the continent barren. A more nuanced simulation could vary fertility over time to simulate periods of growth and contraction, and that sort of jagged growth pattern could very well result in loss of genes, particularly if sustained for a few generations following a bottleneck event.

- Early growth rates soon after a colony’s founding are very important to the concept of genetic drift. If high growth over a few generations had resulted in much more than 10,000 people with a sex-linked gene of Old-World origin, it would’ve taken something on the scale of a meteor to get rid of them. For those genes to have died out, either low growth and warfare would’ve had to have taken them out early, or they would’ve had to have kept it rare enough (after mixing with the local population) for it to have been feasibly wiped out by the various bottlenecks.

From what I can tell, you can’t have early and sustained levels of high population growth and also have missing DNA. This is a bit of a problem, because the Book of Mormon suggests the former while the current evidence suggests the latter. The only way around this, in my mind, is for Nephi’s people to have mixed with the local population very early on. This would both help to explain apparent early increases in the Nephite population and set the stage for genetic drift and population bottlenecks to feasibly remove Lehi’s DNA.

Now enjoy my amateur python code.

Python Code

import random #importing the package used to distribute the number of surviving children

import statistics #importing the package used to calculate averages and maximums

#code represents high fertility estimates; low fertility values in commented parentheses

#20 generations until 3 Nephi destruction

#32 generations until Moroni

#64 generations until Columbian exchange

generation=0 #declaring variables

genes=50

iteration=0

gen_exit=[]

genes_exit=[]

person=genes

rando=0

gen_num=0

genes_num=0

average=0

maximum=0

while iteration<1000: #setting the number of iterations of 80 generations that the simulation will run

while genes>0 and genes<10000 and generation<80: #setting parameters when each iteration will exit

while person>0: #a loop set to run for each person with the gene at the start of each generation

if generation==20 or generation==32: #indicating the generations with bottlenecks

rando=random.randint(1,100) #a random value that will determine if each person survives

if rando<=75: #the percentage out of 100 that will die to the bottleneck

genes-=1 #decrementing the number of genes if a person dies

person-=1 #moving the simulation to the next person with a gene

#print(‘H1: ‘,’person: ‘,person,’; ‘,"genes: ",genes,’; ‘,’gen: ‘,generation)

else: # if the person survives

person-=1 #moving the simulation to the next person

#print(‘H2: ‘,’person: ‘,person,’; ‘,"genes: ",genes,’; ‘,’gen: ‘,generation)

elif generation==64: #indicating the generation where disease epidemics occurred

rando=random.randint(1,100)

if rando<=90: #the percentage out of 100 that will die to the bottleneck

genes-=1

person-=1

#print(‘H1: ‘,’person: ‘,person,’; ‘,"genes: ",genes,’; ‘,’gen: ‘,generation)

else:

person-=1

#print(‘H2: ‘,’person: ‘,person,’; ‘,"genes: ",genes,’; ‘,’gen: ‘,generation)

else: #conditions if it is not a bottleneck generation

rando=random.randint(1,1000)

#print(‘Rando: ‘,rando)

if rando<=1: #(2) #number out of 1000 who will pass on six (four) extra genes

genes+=6 #(4)

person-=1

#print(‘H3: ‘,’person: ‘,person,’; ‘,"genes: ",genes,’; ‘,’gen: ‘,generation)

elif rando<=6: #(16) #number out of 1000 who will pass on five (three) extra genes

genes+=5 #(3)

person-=1

#print(‘H4: ‘,’person: ‘,person,’; ‘,"genes: ",genes,’; ‘,’gen: ‘,generation)

elif rando<=24: #(85) #number out of 1000 who will pass on four (two) extra genes

genes+=4 #(2)

person-=1

#print(‘H4: ‘,’person: ‘,person,’; ‘,"genes: ",genes,’; ‘,’gen: ‘,generation)

elif rando<=74: #(295) #number out of 1000 who will pass on three (one) extra genes

genes+=3 #(1)

person-=1

#print(‘H4: ‘,’person: ‘,person,’; ‘,"genes: ",genes,’; ‘,’gen: ‘,generation)

elif rando<=192: #(664) #number out of 1000 who will pass on two (zero) extra genes

genes+=2 #(0)

person-=1

#print(‘H4: ‘,’person: ‘,person,’; ‘,"genes: ",genes,’; ‘,’gen: ‘,generation)

elif rando<=409: #number out of 1000 who will pass on one extra gene

genes+=1 #this section not used in low fertility scenario

person-=1

#print(‘H4: ‘,’person: ‘,person,’; ‘,"genes: ",genes,’; ‘,’gen: ‘,generation)

elif rando<=703: #number out of 1000 where number of genes remain stable

genes+=0 #this section not used for low fertility scenario

person-=1

#print(‘H4: ‘,’person: ‘,person,’; ‘,"genes: ",genes,’; ‘,’gen: ‘,generation)

elif rando<=1000: #number out of 1000 where a gene is lost

genes-=1

person-=1

#print(‘H4: ‘,’person: ‘,person,’; ‘,"genes: ",genes,’; ‘,’gen: ‘,generation)

person=genes #resetting the number of people to reflect the new number of genes

#print(‘Gen: ‘,generation,’ Genes: ‘,genes)

generation+=1 #moving to the next generation

print(‘gen: ‘,generation,’; ‘,’genes: ‘,genes)

gen_exit.append(generation) #appending the generation where the simulation exited to a list

genes_exit.append(genes) #appending the number of genes present when the simulation exited

iteration+=1 #moving to the next iteration

genes=50 #resetting the number of genes at the start of the simulation

generation=0 #resetting the generation number

for x in gen_exit: #counting the number of iterations where the simulation ran to 80 generations

if x==80:

gen_num+=1

for x in genes_exit: #counting the number of iterations where there was zero genes left

if x==0:

genes_num+=1

average=statistics.mean(gen_num) #calculating the average number of generations at exit

maximum=statistics.max(genes_num) #calculating the max number of genes at exit

print(‘Number lasting 80 generations: ‘,gen_num)

print(‘Number with extinct genes: ‘,genes_num)

print(‘Max genes: ‘,maximum)

print(‘Average exit generation: ‘,average)

Some estimates of the decimation of native american populations with the introduction of europeans and their diseases is 90%. https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/native-americans-colonial-america/#:~:text=European%20settlers%20brought%20these%20new%20diseases%20with%20them,as%20much%20as%2090%20percent%20of%20their%20population.

And the genetic bottleneck that likely resulted in the genocide of the Nephites being unknown, I don’t know how the evidence can be weighed at anything other than 0 for this factor. A negative 3 is not supported.

Hi Collin:

Both Loren Spendlove and Bruce Dale agree with you (see below). There is simply not enough genetic evidence one way or the other to either confirm or refute the Book of Mormon’s claims. However, to be picky, the effect of this conclusion on the statistics is to multiply the prior skeptical by one, not by zero. 🙂

Bruce

Thanks for the comment Collin. I agree that there are a lot of factors that should lead us to be unsurprised that Lehi’s DNA has yet to be detected. But, in the spirit of giving the critics the fairest possible shake, I don’t think I could assign an evidence score of 0 (which, to clarify Bruce’s comment, corresponds to a Bayes factor of 1). There are a number of cases where war or genocide or famine or disease or other bottlenecks could’ve wiped out a people’s genetic legacy, but their legacy remains nonetheless. If a study turned up tomorrow showing a middle-eastern genetic contribution in the Americas at the right timeframe, I don’t think any faithful member would be surprised that such a trace could’ve survived, given what we read in the BofM. In that context, the current lack of DNA evidence can be considered at least a little unexpected. And in the context of the rest of the evidence discussed in this series, a -3 doesn’t make much of a splash. I feel pretty comfortable with the score as-is, though if you have a robust argument for why the probability of observing that lack HAS to be higher than I have it here, I’d be willing to give it a look.

Moroni: “We are a remnant of the seed of Jacob; yea, we are a remnant of the seed of Joseph.” (Alma 46:3)

Kyler: “That the ancients should care more about lineal ancestry than genetic relatedness should be obvious. That the ancients should care more about lineal ancestry than genetic relatedness should be obvious from the fact that even the most basic of genetic mechanics were unknown in Joseph’s (let alone Lehi’s) day.”

Armand Mauss: “The Mormon prophet Joseph Smith was among those who took literally the relationship between lineage and blood, declaring in a 1839 sermon that converts from Gentile lineages would miraculously undergo an actual change of blood, making their conversion a somewhat more physical experience than would be the case for those converts of literal Israelite descent.”

John Sorenson: “Archaeology, linguistics and related areas of study have established beyond doubt that a variety of peoples inhabited virtually every place in the Western Hemisphere a long time ago.”

Lehi: “It is wisdom that this land should be kept as yet from the knowledge of other nations; for behold, many nations would overrun the land.” (2 Nephi 1:8)

John Sorenson: “Latter-day Saints generally have supposed that the “other nations” were the Gentile (Christian) nations of Europe who began to reach the New World only 500 years ago. To believe so requires limited imagination.”

Armand Mauss: “Joseph Smith and the entire founding generation of Mormonism believed that the descendants of the Lamanites were first and foremost the tribal aborigines of North America. The Book of Mormon was their authentic ancient history, and the attributions and prophecies therein about the Lamanites, both positive and negative, referred to the destiny of the American Indians.”

John Sorenson: “[Jarom 1:5-6] is so contrary to the record of human history that it cannot be accepted at face value.”

Ezra Taft Benson: “[The Book of Mormon] was written for our day. The Nephites never had the book; neither did the Lamanites of ancient times. It was meant for us. Mormon wrote near the end of the Nephite civilization. Under the inspiration of God, who sees all things from the beginning, he abridged centuries of records, choosing the stories, speeches, and events that would be most helpful to us.”

John Sorenson: “I suggest that we should discount this dark portrait of the Lamanites on account of its clear measure of ethnic prejudice and its lack of first-hand observation on the part of the Nephite record keepers.”

According to the Book of Mormon, there was a universal flood around the year 3,000 B.C. killed everybody on the planet (Alma 10:22), including everybody on the western hemisphere. There was a literal tower of Babel and a literal confoundment of the languages (Ether 1:33). When the Jaradites arrived in the New World around 2200 B.C., they were the *only* people there. The Jaradites were all destroyed except for one man, Coriantumr (Ether 15:14-32). Around 600 B.C. the Lehites came from Israel to the new world, followed by the Mulekites in 587 B.C. When they found each other after 350 years it was noteworthy, just as it was noteworthy when they found the lone surviving Jaradite (Omni 1:27). That’s because nobody else was there. The only other “others” explicitly mentioned in the book are Christopher Columbus and the white-skinned immigrants from Europe in the 17th-19th centuries (1 Nephi 13:12-15).

The reason critics see DNA as a slam dunk isn’t because they are “misreading” the Book of Mormon. It is because they are taking what it actually says at face value. This is precisely what almost all believers—both Prophets and faithful members– have done since the very beginning.

John Sorenson has reinterpreted the Book of Mormon to make it less implausible. Yes, when you disregard the implausible parts and exercise limitless imagination, what’s left can’t be proven false. That’s true by definition. However, I fail to see the point. Why would God go to such miraculous lengths to give us the Book, but fail to tell His Prophet that its teachings are the mere prejudices of an ancient myopic civilization that aren’t particularly true or relevant?

I have heard that argument. It is rather simplistic. What it suggests, without any corroboration, is that any document must be read literally, and especially one claiming antiquity. I’m not sure you will get any historian to agree that documents exist (of any complexity) that do not require interpretation. Indeed, history continues to be rewritten precisely because sources are understood in new ways.

So, is there a way around the “limitless imagination”? Of course. Historians deal with it. Ethnohistorians are well aware of it. There are limits and controls, many of which suggest that the way to understand any document from history is to understand the text in context. Second, when there is a translated text from history, the translation must also be understood. While that is more challenging without an original, it is hardly impossible. There are a number of ancient documents surviving in translation but not the original language.

Rather than a substantive critique, you are creating the strawman argument that if what we understand in the modern world conflicts with what a text says, it must be literal and therefore wrong. For example, you note “According to the Book of Mormon, there was a universal flood around the year 3,000 B.C.” First, that is technically incorrect because the Book of Mormon doesn’t date it. Second, the Bible also says that there was such a flood, and any text that claimed inheritance from that literary culture would be surprising if it didn’t conform to the model. What the Bible says can be argued as to whether or not there was a historical flood, but not that there was a historical record (multiple, in fact) that said there was. That is a very different proposition and the two should not be confused.

Brant: “Rather than a substantive critique, you are creating the strawman argument that if what we understand in the modern world conflicts with what a text says, it must be literal and therefore wrong…”

Not exactly. My point is that the “others” hypothesis contradicts the explicit story in the Book of Mormon *and* the myths they told themselves about who they were. As an analogy, the myths of the Bible talked about the Israelites having a promised land that was occupied by enemies, and has all sorts of battles that may or may not have any basis in reality as they tried to carve out a kingdom for themselves. When you look at real-world Israelites, these myths about their conflict with others in the region are congruous with the real-world existence of others and the conflicts they had with them.

In contrast, imagine 50 generations of Nephites passing on myths about how they were a chosen people living in a promised land that was kept secret by God from other nations. If in reality they were quickly integrated into a massive population of the “others,” are these really the myths they’d be telling themselves?

Once again, this is a demonstration of my point. You assume that the Bible is the model for all ancient documents. That is incorrect. For example, the Maya spoke of the Western Lords. They never designated who they were. We know from other evidence what they were probably speaking of. In the Book of Mormon, the text only pays attention to a small set of people. The Nephites never access their living space through conflict, and all conflict comes from what we are told, categorically, is a collective term “Lamanites” (similar to “gentiles”).

In the actual descriptions of the text, however, we find the evidence that there had to have been other people. Think stories in Genesis where Cain is afraid of all of the people who might kill him (not to mention where their wives came from). Such details were not important to the story, but reading between the lines, the story can be reconstructed.

Complaining that the Book of Mormon can’t be an ancient text because it doesn’t meet modern expectations is a circular argument at best.

And deeper we go into the motte. Let’s take these one at a time.

“The Mormon prophet Joseph Smith was among those who took literally the relationship between lineage and blood”

Actually, I read that statement as a pretty solid disconnect between lineage and blood (as in it’s lineage that’s important, including adoptive lineage, and blood is so secondary as to be mutable). Also makes a pretty cool metaphor when you think about it, and it’s not particularly surprising that Joseph would take the metaphor literally in the absence of better information. I’ll get to that in Episode 18, though.

“It is wisdom that this land should be kept as yet from the knowledge of other nations”

The context for Lehi’s statement is pretty important. There’s little reason to think he’s talking about the entire continent here, and it’s early enough on that they might not have run into that many people (if any) on the more sparely populated Western coast. Sorenson’s reading seems reasonable here.

“Joseph Smith and the entire founding generation of Mormonism believed that the descendants of the Lamanites were first and foremost the tribal aborigines of North America.”

And they are, of course, allowed to be wrong about such things. And the likelihood of Lehi’s lineage spanning the continent probably makes them right anyway, even if it might be for the wrong reasons.

“[The Book of Mormon] was written for our day. ”

I don’t imagine Sorenson having a problem with this one, so I’m not sure there’s any contradiction. The book can be both inspired and imperfect, as the book itself states.

“It is because they are taking what it actually says at face value.”

In my mind, it’s because they would rather people didn’t actually use their brains when thinking about the BofM. The objection to nuanced critical thinking reminds me of this more than a little bit:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dx32b5igLwA

To summarize, there are two ways to interpret the basket of evidence for “others” that Sorenson presents.

1- The Book of Mormon is full of inconsistencies, implausible details, and contradictions with known reality. Some of those problems partly go away if we introduce “others” by reinterpreting the explicit story of the Book of Mormon *and* disregarding, watering down, and reinterpreting the Book’s explicit religious messages about the promised land, the covenant people, and the important distinction between Jews, Nephites, Lamanites, and gentiles.

2- The Book of Mormon is full of inconsistencies, implausible details, and contradictions with known reality. This is easily explained by the hypothesis that it is 19th century American fiction.

For the record, I do agree with you that if a guy named Lehi or anything else would have arrived on the shores of the Americas, he and his band would have either died or been absorbed into the local population. That is true. And if he would have survived, his specific DNA would have likely disappeared into the greater population. Sure. My issue with that is that the Book of Mormon simply isn’t a story about a party of 40 or so who were quickly absorbed into a population of gentiles.

In fact, that very idea contradicts the Book of Mormon. God didn’t tell Lehi that he didn’t need to bring any women with him to the promised land because he and his sons would be able to be quickly absorbed into the gentile population who already lived there. Rather, “it was not meet for him, Lehi, that he should take his family into the wilderness alone; but that his sons should take daughters to wife, that they might raise up seed unto the Lord in the land of promise.”

So what is your hypothesis here, exactly? If the hypothesis is some people sailed to the new world in 600 B.C. and integrated with the native population then sure, that is plausible. But if your hypothesis is that the Book of Mormon is a basically accurate history of their civilization that contains basically true promises from God, that is something else entirely.

“The Book of Mormon is full of inconsistencies, implausible details, and contradictions with known reality.”

“Full” is probably an exaggeration here, and there are probably quite a few details that you see as implausible that I don’t, but I get your general point. And I understand that would be a problem for those who hold up Nephi and Mormon as near-deified figures of unimpeachable competence. But you know what else has those things? Authentic ancient historical records.

(And the idea that the book is full of inconsistencies specifically seems to have been lost on the many well-informed folk who see it as an exceptionally consistent book. You can see Episode 17 for that particular discussion.)

“My issue with that is that the Book of Mormon simply isn’t a story about a party of 40 or so who were quickly absorbed into a population of gentiles.”

It is that story, on at least two fronts (Mulekite and Lamanite). That the Nephite story doesn’t also follow that path is perhaps unusual (thus the p = .02 estimate for that part of the analysis), but not unheard of in the historical record.

In terms of your point to Brant regarding mythology, if the political point of the small plates is to establish Nephi’s legitimacy as king, then that would certainly be a convenient mythology to put forward. (And remember that aside from the small plates this is very much an edited text, reflecting the biases and perspectives of its human editor.)

And one of those biases, on both ends, is that the book wasn’t intended as a complete history of the state, a la Kings and Chronicles. It mentions political elements when it needs to (e.g., integration with a rival line of apparently equal legitimacy in Zarahemla and the Mulekites), or when Mormon has a clear interest (i.e., the war chapters), but it’s not surprising that a lot of the details would fall through the cracks.

“So what is your hypothesis here, exactly?”

I don’t see those two hypotheses as mutually exclusive. We’re just operating on different definitions of “basically accurate”. My expectations of accuracy come more from Herodotus and other ancient historians (and, for that matter, the Bible). I’m not sure what bar of accuracy you’d expect out of the Book of Mormon, but it doesn’t seem to be one based in the reality of record keeping in the ancient world.

Ultimately, though, I don’t think our two positions are that far off. We both agree that it would be possible for the DNA evidence to be lost, and that such would’ve probably been the case for the Lamanites and Mulekites as described in the text. We both agree that the description of the Nephites doesn’t present a clear-cut case for early mixing with Inidgenous inhabitants. I’ve worked to incorporate that into the analysis, and though you might prefer an even smaller probability estimate, you seem to consider what I’ve done an acceptable start, pending further data.

Thanks Billy! Looking forward to talking about the witnesses with you this week.

Thanks Kyler.

One quick question before we move on. You said, “We both agree that the description of the Nephites doesn’t present a clear-cut case for early mixing with indigenous inhabitants.”

What is your basis for agreeing with me on this point rather than with Sorenson? According to the Sorenson link you provided, the text clearly implies the Nephites completely integrated with the natives from the very beginning, too. In his words:

“Within a few years Nephi reports that his people “began to prosper exceedingly, and to multiply in the land” (2 Nephi 5:13). When about fifteen years had passed, he says that Jacob and Joseph had been made priests and teachers “over the land of my people” (2 Nephi 5:26, 28). After another ten years, they “had already had wars and contentions” with the Lamanites (2 Nephi 5:34). After the Nephites had existed as an entity for about forty years (see Jacob 1:1), their men began “desiring many wives and concubines” (Jacob 1:15). How many descendants of the original party would there have been by that time?

“…The text and context of [the Sherem] incident would make little sense if the Nephite population had resulted only from natural demographic increase….

“The reports of intergroup Fighting in these early generations also seem to refer to larger forces than growth by births alone would have allowed….”

The text of the Book of Mormon refers to the Laminates as the *seed* of Nephi’s brothers, and it juxtaposes the seed of Nephi’s brothers with the gentiles.

The Lamanites being a lost remnant of the House of Israel isn’t incidental to the Book of Mormon—it is the very point. The Book of Mormon explicitly says the only people in the land of promise are the ones God brought here and if they fall away, they will be wiped out. That is what it says happened to the Jaredites.

The purpose of isolating the promised land for God’s chosen people was to maintain the purity of the Israelite seed—of their dna. Positing that the Lamanites are somehow the “seed” of Israel yet are genetically indistinguishable from gentiles of Asian descent contradicts the fundamental message of the book.

For details on how Mormons started believing this in 1830–not 1981–see All Abraham’s Children: Changing Mormon Conceptions of Race and Lineage by Dr. Armond Mauss.

Out of an abundance of conservatism I’ll use Kyler’s estimate on this point, which updates my odds against historicity to 4-million-to-one.

” The text of the Book of Mormon refers to the Laminates as the *seed* of Nephi’s brothers”

It’s very telling that this is the motte to which critics try to retreat when arguing for the strength of DNA evidence (and every critic I’ve discussed this with has done so). Such critics generally know full well that they can’t lean on the science itself to strengthen this particular point, so they depend on their own rigid misreadings of the Book of Mormon or church leaders to try to do their work for them.The idea that “seed” or ancestry somehow requires genetic inheritance is not, in my mind, a defensible position. If Lehi was a real person with real descendants, he would almost certainly be the ancestor of nearly everyone on the American continent by the time Columbus arrived (in terms of family tree), even without having a single allele surviving to the present day.

That the ancients should care more about lineal ancestry than genetic relatedness should be obvious from the fact that:

1) Even the most basic of genetic mechanics were unknown in Joseph’s (let alone Lehi’s) day.

2) When tracing our own family trees, genetic relatedness is, even today, almost entirely irrelevant.

My dad was adopted, but I very much consider his adopted parents my grandparents, and still would even if I ever wanted the adoption papers unsealed (my dad hasn’t wanted to, to this point–a position I very much understand and respect). I claim the various adventures and exploits of the storied Rasmussen line as much as I do my Cuban line on the other side. Somehow neither of those real human connections depend on the material contained within my cell nuclei.

“I’ll use Kyler’s estimate on this point”

I’m glad that so far my takes on the negative evidence appear to be acceptable to you. Perhaps that should give me confidence that my views on the positive evidence aren’t as far out to lunch as you’ve so far suggested.

“which updates my odds against historicity to 4-million-to-one.”

And I appreciate how you continue to construct your own living representation of the unreasonable skeptics I discussed in my opening post–skeptics who will never for a second allow anything about Joseph or the BofM to be unexpected or difficult to explain, and who appear committed to only accounting for the negative evidence against it. I look forward to watching your posterior as it follows its undeviating course away from authenticity.

“What is your basis for agreeing with me on this point rather than with Sorenson?”

I agree with Sorenson that the hints are there in the text, and that in many ways the text makes more sense with others present than without.

I agree with you that these hints don’t represent a clear-cut case–that a plain reading of the text would favor no interaction with others on the part of the early Nephites, and that seeing it otherwise requires connecting a few relatively obscure dots. I find these dots compelling but not conclusive.

I believe that the Nephites did interact with others, but I can definitely see the critical perspective in terms of the text itself.

Kyler, as you briefly explain above, based on material culture (eg. pottery) archaeologists have long believed that the Philistines were the infamous “sea peoples” from Crete or other locations around the Mediterranean. In 2019, human remains from a Philistine cemetery in Ashkelon were analyzed for the first time with some very interesting results. The researchers state:

“The ancient Mediterranean port city of Ashkelon, identified as “Philistine” during the Iron Age, underwent a marked cultural change between the Late Bronze and the early Iron Age. It has been long debated whether this change was driven by a substantial movement of people, possibly linked to a larger migration of the so-called ‘Sea Peoples.’ Here, we report genome-wide data of 10 Bronze and Iron Age individuals from Ashkelon. We find that the early Iron Age population was genetically distinct due to a European-related admixture. This genetic signal is no longer detectible in the later Iron Age population. Our results support that a migration event occurred during the Bronze to Iron Age transition in Ashkelon but did not leave a long-lasting genetic signature.”

By analyzing human Philistine remains from different time periods the researchers were able to determine that the unique European DNA footprint of the earlier Philistines had disappeared from the later Philistines in just a 200-year period. Even though the later Philistines were still culturally Philistines they were no longer generic matches for their ancestors. To quote the authors of the study:

“We find that, within no more than two centuries, this genetic footprint introduced during the early Iron Age is no longer detectable and seems to be diluted by a local Levantine- related gene pool.”

So, even though they are still culturally Philistines, due to mixing, the later Philistines are no longer genetically identifiable as Philistines. They have become genetically indistinguishable from the “local Levantine-related gene pool.” This might serve as a good comparison for the arrival in the Americas of smaller Lehite or Mulekite groups that eventually mixed with larger local groups.

Source: https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/5/7/eaax0061

Loren,

Thank you. This is an additional piece of information that tends toward the same conclusion I had already come to on the genetics issue, i.e., the DNA evidence cannot be used to either confirm or deny the authenticity of the Book of Mormon.

Thanks Loren. This is a great study, and one that appears to have come out since I initially drafted this episode. It demonstrates clearly the possibility of genetic evidence being lost to time, and also how difficult it might be to track down ancient DNA sources unless we know very clearly where to look.

For me, the key problem is that we do not have a “control group”. We just do not know what survived of the DNA endowment brought to the Americas by the three migrations mentioned in the Book of Mormon against which we are to compare Native American DNA?

The Book of Mormon does not rule out other migrations not recorded in the Book of Mormon and it does not rule out survivors from one migration remaining even if their societies are destroyed. To say that a society is destroyed does not require that every individual in that society perish. Many may have lived to pass on their DNA.

The Jaredites came from Central Asia about the time of the tower. They were always fighting, splitting off and founding new colonies in the New World. So we can’t rule out the possibility that some of the colonies survived the war of mutual extinction that finally ended the only Jaredite colonies that we do have record of. If some such colonies survived, then we have Central Asian DNA in the original New World genetic material.

We know even less about the Mulekites. Their own oral history said that they came from Jerusalem around 600 B.C. But we don’t know what the genetic makeup of the Mulekite immigrant group was. When these Mulekites mingled with a small portion of the Lehite group in about 130 BC, they were much more numerous than the Lehites. To assume that the Lehites did not intermarry with the Mulekites is an assumption that cannot be proven one way or the other.

Lehi led his wife (Sariah) and sons and another family headed by Ishmael and a former servant/slave named Zoram out of Jerusalem. Israelites were forbidden to make slaves of other Israelites, so it is likely that Zoram was not of Israelite descent, but we don’t know what his ancestry was.

Lehi descended from Joseph through Manasseh. Manasseh was the son of Joseph, the husband of Asenath, the daughter of the high priest of On in Egypt. Asenath was therefore an Egyptian and may have passed her DNA down to her descendants, including Lehi.

We don’t know the ancestry of Lehi’s wife, Sariah. Presumably she was “Israelite”. But we don’t know that and we also don’t know what “Israelite” DNA was like in 600 BC. That is a really big problem for drawing any conclusions from DNA evidence. Also, we don’t know Ishmael’s ancestry, but his name strongly suggests at least some Arab/Bedouin progenitors.

The Lehite colony divided itself into two groups shortly after arriving in the New World. We do not know to what extent, if any, these two groups intermingled with peoples already inhabiting the Americas. These two groups were political/religious, not ethnic, and there was a lot of mixing and wars between them.The Lamanite group destroyed the Nephites in about 400 AD.

“Destroyed” means that Nephite society was unmade, it does not mean that all Nephites were killed. In fact, we are informed in the Book of Mormon that some of these Nephites deserted over to the Lamanites. Thus we have no idea what genetic lines were lost from the initial Lehite colony in almost a millennium of warring (600 BC to 400 AD).

We also don’t know what happened to the surviving Lamanite group in the 1100 years between the end of Book of Mormon history and the arrival of the Europeans. We don’t know if they intermarried with subsequent migrations, or with previous migrations not mentioned in the Book of Mormon. We don’t know how much of their own DNA pool they destroyed in the wars that we know were a prominent feature of aboriginal American life prior to the Conquest.

Finally, we know that the European conquest of the New World led to an enormous extermination of Native American peoples through “guns, germs and steel” as documented by Jared Diamond. It has been estimated that the population of the Native Americans was reduced by over 90% during the three centuries or so of the European conquest of the Americas. This is genocide on a truly enormous scale and therefore loss of DNA on a huge scale.

Okay, that’s it. That is what the Book of Mormon says about the genetic background of its three migratory groups and the

possible survival of the DNA of such groups. We have the Jaredites (central Asian, unknown DNA survival), the Mulekites (unknown genetics, unknown DNA survival) and the Lehites (likely Arab, Egyptian, unknown DNA, Israelite DNA…whatever Israelite DNA was in 600 BC, and also unknown DNA survival) and Zoram (unknown genetics and unknown DNA survival).

Thus, among many other problems, we simply don’t know what our “control group” is. We just don’t know the DNA endowment brought to the Americas by the three migrations mentioned in the Book of Mormon against which we are to compare Native American DNA to test the authenticity of the Book of Mormon.

After considering the evidence and the arguments, I think that current DNA evidence simply cannot be used to either confirm or deny the migrations described in the Book of Mormon. The available data are not adequate to the task.

All great points, Bruce. Definitely a lot of nuance to be taken into account here, all of which would deserve to be discussed in detail if there was ever a book-length treatment. (Ugo! Write me a book please!)

My general point is that, even if you ignore a lot of this nuance, and accept the general premise that Lehi and Sariah would’ve left a clear near-eastern genetic legacy, it’s not nearly enough to represent a critical strike.

Reply to Kyler

Yup!

Quick note on autosomal DNA. A child will have 50% from each parent, but NOT 25% from each grandparent. That’s where it gets a little more complicated. You get half your parent’s DNA, but WHICH half is the question. It’s a mix of genetics from each grandparent, but it’s not a 50/50 split. By the time you’re 3 or 4 generations back, the signal can get very hazy or even non-existent for some lines.

Thanks Zach. You’re correct. It averages out to 25% from each grandparent across all individuals, but in each individual case you’re rolling the dice (and potentially rolling each ancestor’s genetic contribution into obscurity).

Even though Rasmussen does mention ancient DNA in passing, he otherwise entirely ignores the need to actually examine skeletal human remains for DNA evidence of any Israelite presence.

The Nephites may have been exterminated, but the Lamanites certainly weren’t, and there should be plenty of ancient evidence of Israelite (Manassite and Judahite) DNA somewhere in the Americas. Not to mention the likely existence of some sort of Mesopotamian DNA attached to the ancient Olmec (Jaredite) civilization.

As to modern DNA evidence, Rasmussen repeatedly suggests that Lehi’s party would likely have mixed with local peoples. However, that is not the pattern exhibited by the Jews (for example) in their long Diaspora: Instead they were determined to remain separate, and they did so for thousands of years. Moreover, geneticist Simon G. Southerton repeatedly declared in 2005: “In 600 BC there were probably several million American Indians living in the Americas. If a small group of Israelites entered such a massive native population it would be very, very hard to detect their genes 200, 2,000, or even 20,000 years later.” “In 600 BC there were probably several million American Indians living in the Americas. If a small group of Israelites, say less than thirty, entered such a massive native population, it would be very hard to detect their genes today.”

Thanks for commenting Robert.

“Even though Rasmussen does mention ancient DNA in passing, he otherwise entirely ignores the need to actually examine skeletal human remains for DNA evidence of any Israelite presence.”