An Old Testament KnoWhy[1]

relating to the reading assignment for

Gospel Doctrine Lesson 36:

“The Glory of Zion Will Be a Defense”

(Isaiah 1-6) (JBOTL36A)

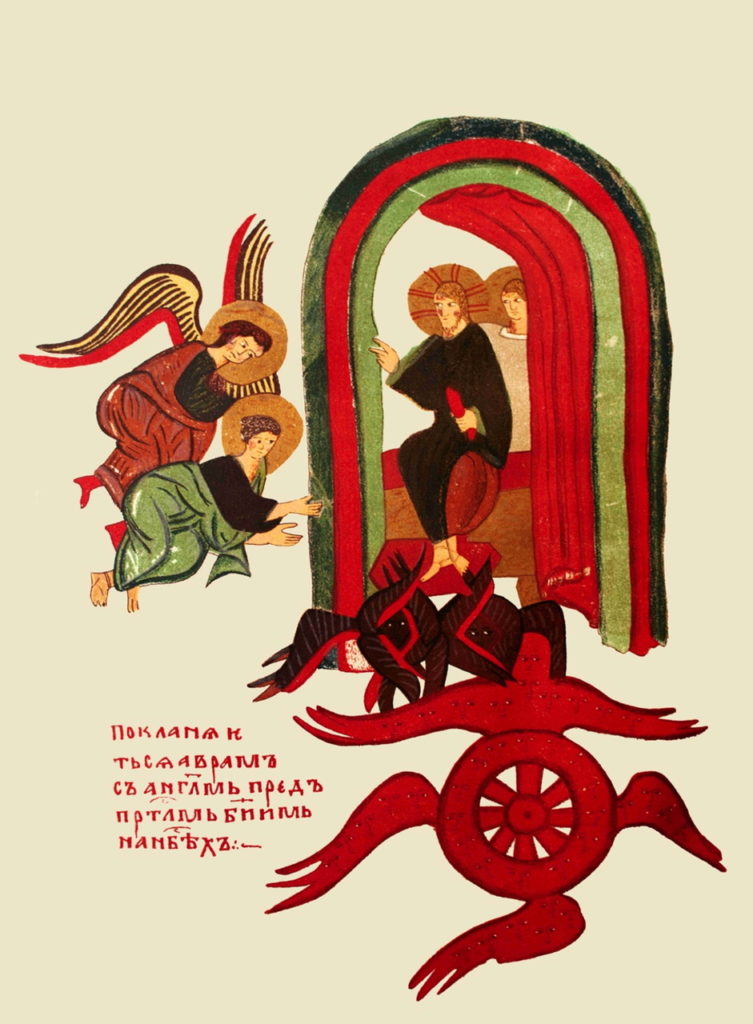

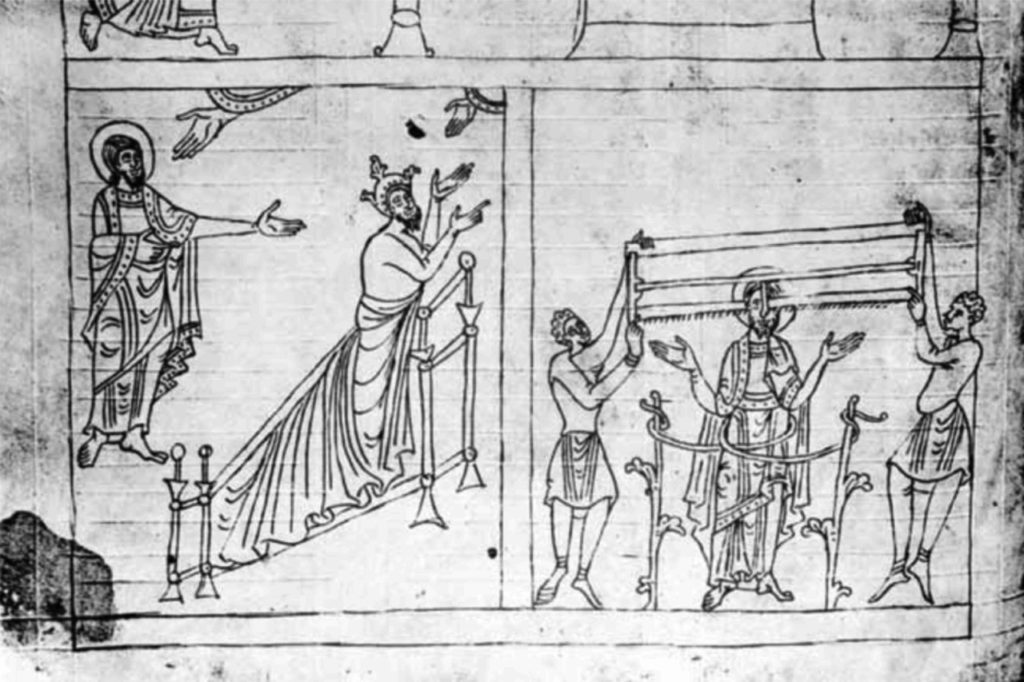

Figure 1. Isaiah’s prophetic commission

Question: The short heavenly vision of Isaiah 6 is almost as difficult to understand as the entire book of Revelation. How might we interpret its symbolism?

Summary: Isaiah 6 is important for two reasons: 1. Historically, it gives us insight into the prophet’s divine commission, received near the beginning of his ministry; 2. Doctrinally, it provides valuable insights into the commissioning of other prophets and individuals who received similar visions. Much of what makes Isaiah’s vision — as well as his prophecies — difficult to understand is his rich poetic imagery, which is often grounded in temple symbolism. This article provides a detailed commentary on Isaiah 6, focused largely on these temple themes. Though none of the temple-related insights are exclusive to Latter-day Saints, their general familiarity with temple doctrines and practices make this chapter more accessible to them than to many other Christians.

The Know

Importance of the Temple in Isaiah’s Ministry

Before delving into the specifics of Isaiah 6, we give Margaret Barker’s overview of the importance of the temple in Isaiah’s ministry:

The temple and its rituals were at the center of Isaiah’s world. Time and again he presents contemporary events as the fulfillment of temple rituals and predicts their outcome accordingly. Whether or not he was the first to do this we cannot tell, but ritual becoming history is one of the characteristics of the Isaiah prophecies.

The temple was sacred space in sacred time. The building had been erected by Solomon about two hundred years before the time of Isaiah as the house of the Lord. The interior was divided into two areas: the Holy of Holies, which represented heaven, and the body of the temple [the Holy Place], which represented the garden of Eden. The two were separated by an elaborately woven curtain [or veil] which represented the material world hiding the Lord from human eyes. Behind the curtain were two huge cherubim which formed the golden chariot throne of the Lord. The best description of this is in 2 Chronicles 3–4, written long after Isaiah’s time but incorporating authentic detail. … The king sat on the throne of the Lord and was worshiped as the Lord.[ 2] …

Isaiah, like John on Patmos centuries later, saw the events of the heavenly world being realized in the history of his own time. He spoke to the king as the divine son who was assured of victory over his enemies; he knew that foes which massed against the Lord and his anointed[ 3] would be destroyed. The role of the royal high priest on the Day of Atonement inspired the Servant poem of Isaiah 53. The festival scenes in Isaiah 2:2–4, 4:2–6, and 25:6–9 depict the temple, both heaven and earth. Isaiah had stood before the heavenly throne.

Who could have had access to all this temple tradition? It is unlikely that it was common knowledge among the populace of Jerusalem. One possibility that cannot be dismissed is that Isaiah was a priest, as were those whose oracles were added to his to form the final scroll. …

[Prophecies] of judgment and salvation probably originated in the temple. … There were also [prophecies in the form of] trial scenes which could have been based on the everyday court procedures of the time, but it is possible that these, too, originated in a temple setting. … There are hymn forms [of prophecy], and again we are pointed to a temple setting. …

Some of the prophet’s words, such as the threat of the Day of Judgment in Isaiah 2:12–19, described what the Lord was about to do. These pronouncements suggest that a prophet had access to the heavenly court where these matters were decided.[ 4] This right was also granted to the high priest,[ 5] and, like Isaiah, he had to have his iniquity taken away before he could enter the presence of God.[ 6] …

On many occasions, however, the prophet spoke not as himself but as the Lord.[ 7] [The prophets] became His mouthpiece, as did the king.[ 8] Something similar was implied of Jesus; the Spirit came upon him and he spoke with authority, not like the scribes.[ 9] He was the Lord.

Historical Setting

Abraham Joshua Heschel gives the following description of the historical setting for Isaiah 6:[ 10]

Under the long reign of Uzziah[, also known as Azariah,[ 11]] (ca. 783-ca. 742 BCE), in fame second only to Sol0mon’s, Judah reached the summit of its power. Uzziah built up the economic resources of the country as well as its military strength. He conquered the Philistines and the Arabians, and received tribute from the Ammonites; he fortified the country, reorganized and re-equipped the army. “In Jerusalem he made engines, invented by skillful men, to be on the towers and the corners, to shoot arrows and great stones” (2 Chronicles 26:15). His success as king, administrator, and commander-in-chief of the arm made him ruler over the largest realm of Judah since the disruption of the Kingdom.

Uzziah’s strength became his weakness. “He grew proud, to his destruction,” and attempted to usurp the power of the priesthood, even entering the Temple of the Lord to burn incense on the altar, a privilege reserved for the priests.[ 12] It was about 750 BCE when Uzziah was stricken with leprosy, and his pace in public [until his death] was taken over by his son Jotham, though actual power seems to have remained with Uzziah.

Commentary

1 In the year that king Uzziah died I saw also the Lord sitting upon a throne, high and lifted up, and his train filled the temple.

In the year that king Uzziah died. About 742-738 BCE. Logically, this vision would have been the inaugural event for Isaiah’s ministry, so it is unclear why the account of it does not appear until chapter 6:

- Some scholars explain the later placement of this vision by suggesting “that it depicts the beginning of a new stage in Isaiah’s career; he receives a new assignment that differs from earlier ones. Supporting this notion is that the first five chapters call on the Judeans to repent, but from this chapter until the last prophecy of Isaiah son of Amoz, the prophet does not call on the Israelites to repent; Isaiah 6:9–10 may account for this difference.”[ 13]

- Avraham Gileadi explains the placement of this vision within the book of Isaiah in terms of his theory that the overall book was deliberately structured in “bifid” fashion. In this seven-part literary structure, the first 33 chapters of the book mirror the last 33 chapters in chiastic fashion. Thus, he sees the prophetic commission of Isaiah in 6:1-11 paralleling chapter 40 and the historical preface in 6:12-13 paralleling chapter 39.

The Lord sitting upon a throne, high and lifted up. Whereas some scholars interpret this phrase as describing “a high and lofty throne,”[ 14] Gileadi,[ 15] more plausibly, reads this phrase as a describing the Lord Himself as “highly exalted,” a divine attribute.[ 16] the skirt of his robe filling the sanctuary. Gileadi comments further:[ 17] “As Solomon’s temple in Jerusalem contained no throne, Jehovah’s throne was not in the temple itself, though it may have appeared to Isaiah above the Ark of the Covenant in the Holy of Holies.”

More broadly described, Isaiah’s vision is of the divine court[ 18] — In other words, according to Jewish scholar Benjamin D. Sommer, “Isaiah sees God and [His] retinue. This is one of many passages indicating that some biblical authors conceive of God as a physical being whom a few people can see.”[ 19]

Margaret Barker further describes the nature of this “throne theophany,” as such experiences are commonly called by scholars, and its parallels elsewhere in the Bible:[ 20]

What we have here is an early description of a throne vision in which a prophet or visionary was taken into the presence of God. The temple and its rituals were believed to make visible on earth the reality of heaven; and so the setting of Isaiah’s vision was both heaven and the temple. In such visions the temple furnishings come alive as their heavenly archetypes.[ 21] Isaiah saw the heavenly throne in the holy of holies,[ 22] the chariot of the two golden cherubim.[ 23] Nobody knows the ultimate origin of such visionary material, but something similar appears in the Songs of the Sabbath Day Sacrifice,[ 24] used by the Qumran community eight centuries after the time of Isaiah: in the Songs the figures on the walls of the temple become the heavenly host worshiping God.

There are other throne visions in the Old Testament: the elders on Mt. Sinai saw the God of Israel;[ 25] Micaiah saw the Lord enthroned in the midst of his hosts;[ 26] Ezekiel saw the throne chariot leaving the polluted temple in Jerusalem[ 27] and appearing to him in Babylon;[ 28] Daniel saw the Ancient of Days sitting on a fiery chariot throne and a human figure approaching him;[ 29] Jesus told the parable of the sheep and the goats, assembled for judgment before the King on his throne.[ 30] 1 Enoch records many such visions, some in detail, others only in fragments,[ 31] but the pattern is the same: a temple setting, a human figure approaching the throne or observing another approach, and the threat of judgment. The best known of these visions is recorded in Revelation 4–5, where John observes the Lamb approaching the throne before the judgment begins.

his train filled the temple. Some commentators try to disambiguate the phrase by translating more precisely (e.g., “the hem of his robe filled the temple,”[ 32] “the skirts of his robe filled the temple”[ 33]), with the phrase signifying “the bottom of God’s robe or the part hanging down from the knees.”[ 34]

J. J. M. Roberts misses the primary, symbolic meaning in this depiction, commenting simply that Isaiah is trying to paint the image “of a God too gigantic to be contained in the temple.”[ 35] Hugh Nibley, however, observed that in ancient Israel, the temple clothing of priests symbolized the heavenly clothing that would be given them in the next life.[ 36] He explained that “the white undergarment is the proper preexistent glory of the wearer, while the [outer garment of the high priest] is the priesthood later added to it.”[ 37] Figuratively speaking, each increase in purity and each resulting increment of power of the wearers of the robe of the priesthood is represented in an addition to the extent of the robe itself, God’s honor and power and glory being the greatest of all.[ 38] Thus, in Barker’s succinct summary, verse 1’s description of “the temple filled with His robe” is an exact parallel to verse 3’s description of “the earth filled with His glory.”[ 39]

Latter-day Saints who understand that the “bring[ing] to pass the immortality and eternal life of man” constitutes God’s “work and glory”[ 40] will appreciate the additional layer of meaning that Barker draws from later Jewish tradition. In that tradition, the robe of God was associated with His entourage, the heavenly host.[ 41] Latter-day Saints know that the angels of God’s heavenly host are not a distinct order of Creation completely separate from humankind, as some Christians believe, but rather comprise the members of the “general assembly and church of the firstborn.”[ 42] These individuals, also described as “just men made perfect,” have been made fit to dwell in the presence of the Lord.[ 43] Thus, figuratively speaking, as God continually progresses in His work to save and exalt His children, the extent of His robe (which symbolically represents His glory) expands to fill the Universe.

Figure 2. Abraham and Yahoel Before the Divine Throne. Sylvester Codex. Photograph by Stephen T. Whitlock. In the illustration,[44] the figure seated on the throne seems to be Christ. His identity is indicated by the cruciform markings on His halo. Behind Him sits another figure, perhaps alluding to the statement that “Michael is with me [God] in order to bless you forever.”[45] Beneath the throne are fiery seraphim and many-eyed “wheels” praising God. The throne is surrounded by a series of heavenly veils, representing different levels of the firmament separating God from the material world—the latter being signified by the outermost dark blue veil. The fact that the veils are depicted as fabric rather than simply a “rainbow effect” is easily revealed by close inspection.

2 Above it stood the seraphims: each one had six wings; with twain he covered his face, and with twain he covered his feet, and with twain he did fly.

seraphims. “Above the throne Isaiah saw the six-winged seraphs (literally “the burning ones”), [probably] the golden pair which formed the throne in the sanctuary; but in Isaiah’s vision they, too, have come alive”[ 46] as the heavenly equivalents of the temple furnishings.

In scripture and tradition,[ 47] the glorious seraphim were symbolized as “fiery flying serpents,”[ 48] figuratively similar to the earthly serpents that were the plague of the children of Israel, and which were symbolized on the pole that Moses lifted up as their means of salvation.[ 49] In visions of the heavenly temple, these burning, godlike beings served as divine messengers, proximal attendants of God’s throne,[ 50] and preeminent members of the divine council. In temple contexts, the essential function of the seraphim was similar to the role of the cherubim at the entrance of the Garden of Eden:[ 51] they were to be sentinels or “keep[ers] [of] the way,”[ 52] guarding the portals of the heavenly temple against unauthorized entry, governing subsequent access to increasingly secure compartments, and ultimately assisting in the determination of the fitness of worshipers to enter God’s presence.[ 53]

Figure 3. Marc Chagall (1887–1985): L’Exode, 1952–1966. “If I Be Lifted Up from the Earth, [I] Will Draw All Men Unto Me” (John 12:32)

In his discussion with Nicodemus,[ 54] Jesus Christ portrayed Himself as the better of all the seraphim and the innermost “keeper of the gate,[ 55] could literally and legitimately assert: “no man cometh unto the Father, but by me.”[ 56]

six wings. There is not much that can be said beyond the literal description in scripture to help us understand the symbolic function of the seraphim wings. In D&C 77:4, the wings of the beasts in Revelation 4:8 are said simply to be “a representation of power, to move, to act, etc.”

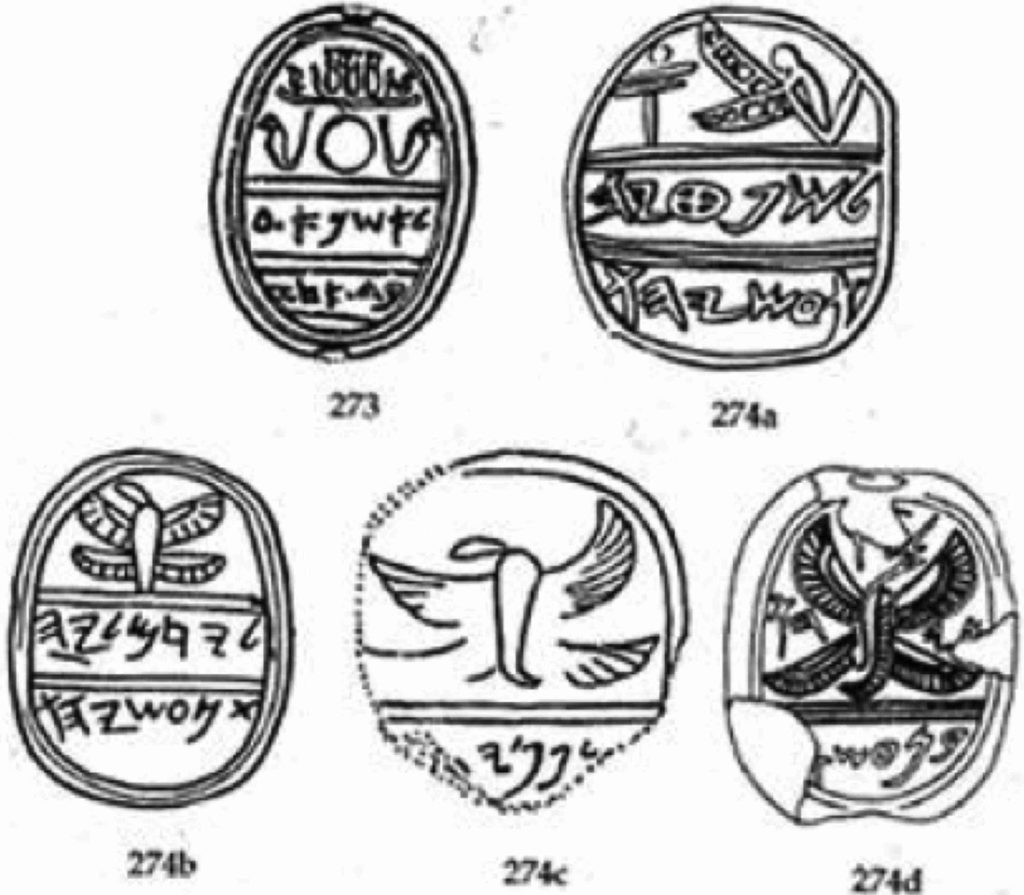

Figure 4. Seal of Ashna with seraph. “Seal 273 portrays Yhwh symbolically as a sun disk wearing a crown (a typical representation in Israelite-Judean art). YHWH is thus portrayed as king, and surrounding him are the seraphs. Seal 274a may portray YHWH as king, sitting on some sort of structure or throne, also attended by a seraph, this time a seraph with wings.”[57]

Adele Berlin comments on the figure above as follows: [ 58]

Representations of seraphs who surround the heavenly throne appear in Judean art of the 8th century, including a seal presenting a picture almost identical to Isaiah’s vision (first published by archaeologists in 1941). The seal belonged to a contemporary of Isaiah’s named Ashna, who was a courtier of King Ahaz. Given the relatively small size of Jerusalem in the 8th c. and Isaiah’s close connections with the royal court (evident in chapter 7 and in chapters 36–39), it is highly probable that Isaiah and Ashna knew each other.

3 And one cried unto another, and said, Holy, holy, holy, is the Lord of hosts: the whole earth is full of his glory.

one cried unto another. The seraphim seem to be singing their song of praise in antiphonal fashion — with different individuals or groups alternating among themselves. Some have suggested “that the Hebrew could mean ‘called in unison.'”[ 59]

Holy, holy, holy. Gileadi observes that the Hebrew superlative “most holy” or “thrice holy” is reserved for Jehovah, whereas the seraphim are described with a single “holy.”[ 60]

Barker[ 61] observes that this is “the song of the heavenly host in 1 Enoch 39:12, where the ‘Lord of hosts’ becomes the ‘Lord of Spirits,’ and in Revelation 4:8, where the Greek for ‘Lord God Almighty’ renders ‘Lord of hosts.'”[ 62]

For many Christians, variants of this song are a regular part of worship services. Benjamin D. Sommer describes the important place this song of praise also has in Jewish tradition.[ 63] It:

serves as the centerpiece of the Kedushah prayer, in which worshipers praise God using angelic liturgy. The Kedushah appears in the communal recitation of the ʿamidah (the main statutory prayer in Judaism), which requires a prayer quorum (Hebrew minyan) of ten. It is also found in services for all mornings, Sabbath afternoons, and Saturday nights in sections that can be recited in private. These verses share several features with other biblical and ancient Jewish texts that describe angelic worship,[ 64] and early Jewish mystical texts known as heikhalot rabbati literature. The common elements among these texts include God’s kingship, glory (Hebrew kabod), and holiness (expressed with the adjective kadosh); the three-fold (in some other cases, seven-fold) repetition of key vocabulary; the motif of the heavenly beings singing together or singing antiphonally.

Scripture and pseudepigrapha recount how those who pass through the veil of the heavenly temple are permitted to do so only after they have learned to speak or sing praises “with the tongue of angels.”[ 65] For example, in the Apocalypse of Abraham, Abraham must recite certain words taught to him by an angel in preparation for his ascent to receive a vision of the work of God.[ 66] In such accounts, once a person has been thoroughly tested, the “last phrase” of welcome is extended to him: “Let him come up!”[ 67] Similarly, an account by Philo describes the great and final song that Moses sang “in the ears of both mankind and ministering angels”[ 68] as part of his heavenly ascent.[ 69] Such a song, figuratively representing the sacred, culminating words of the heavenly temple entrance liturgy, seems to be precisely what the seraphim are modeling for Isaiah in his vision.

4 And the posts of the door moved at the voice of him that cried, and the house was filled with smoke.

The posts of the door moved. The doorposts may refer to the wooden structure on which the veil of the temple was mounted. The shaking of the doorposts at the sound of the voice recalls the jarring description in the Apocalypse of Abraham of a voice “like the roaring of the sea”[ 70] that Abraham heard after he recited the angelic words and was brought through the veil into the presence of the fiery seraphim surrounding the heavenly throne.[ 71]

the voice of him that cried. Although the natural referent for the voice would be one of the seraphim, parallels in similar visions favor the conclusion that it was the voice of God Himself. Barker[ 72] writes that Isaiah’s experience is “exactly as is recorded of Moses in the tabernacle: ‘from between the two cherubim … I will deliver to you all my commands,’[ 73] and of St. John, who saw a heavenly figure in the midst of the seven temple lamps.”[ 74]

the house was filled with smoke. Barker[ 75] comments that the smoke was “probably incense [from the temple altar], but compare 1 Kings 8:10–11, the consecration of Solomon’s temple, where the priests were unable to stay in the sanctuary because of the cloud of the glory.”

5 ¶ Then said I, Woe is me! for I am undone; because I am a man of unclean lips, and I dwell in the midst of a people of unclean lips: for mine eyes have seen the King, the Lord of hosts.

I am undone. “A double-entendre that could also be rendered ‘I am silenced’[ 76]” or “struck dumb.”[ 77] “As often occurs when a person sees God with his physical eyes, he is physically impaired.”[ 78] “Jerome, in his Commentary on Isaiah, says that this indicates the prophet’s regret either that he did not join in the song of the angels or that he did not rebuke Uzziah’s sin in entering the sanctuary.”[ 79]

I am a man of unclean lips. “Isaiah was overcome with a sense of his own uncleanness, a cultic term, a condition which should have excluded him from the sanctuary.”[ 80] While service in Israelite temples under conditions of worthiness was intended to sanctify the participants. However, as taught in Levitical laws of purity, doing the same “while defiled by sin, was to court unnecessary danger, perhaps even death.”[ 81]

for mine eyes have seen the King. Barker has written extensively about various effects of Israel’s apostasy. These effects were particularly evident during the time of Josiah, when sweeping reforms of temple practices were carried out.[ 82]

In its zeal to eradicate heretical beliefs and practices, the movement condemned those who had tried to remain faithful to the older priestly traditions and the religion of the patriarchs. Among other things, the reformers denied that God could be seen, even though this idea was well-attested in scripture:[ 83]

Isaiah saw the Lord, as did Ezekiel,[ 84] Moses, who spoke with God face-to-face,[ 85] and the elders who ascended Sinai with him.[ 86] Other texts deny such [visions. They say that] Moses heard only a voice at Mt. Sinai; he saw no form,[ 87] and he was told that he could not see the face of God and live.”[ 88] The temple setting of the visions suggests that they originated there, perhaps in the traditions of the Jerusalem priesthood. It was the Deuteronomists, reformers of the temple cult, who were opposed to this aspect of the tradition.

Barker further observed:[ 89]

To see the glory of the Lord’s presence — to see beyond the veil — was the greatest blessing. The high priest used to bless Israel with the words: “The Lord bless you and keep you: The Lord make his face to shine upon you, and be gracious unto you: The Lord lift up his countenance upon you, and give you peace.”[ 90] … Seeing the glory, however, became controversial. Nobody knows why. There is one strand in the Old Testament that is absolutely opposed to any idea of seeing the divine. … [On the other hand,] Jesus said: “Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God”;[ 91] and John saw “one seated on the throne.”[ 92] There can be no doubt where the early Christians stood on this matter.

the King, the Lord of hosts. Barker[ 93] explains the use of these names for God, highlighting the idea of angelic “hosts” as another target of the over-zealous reformers of Israelite temple worship:

The King[ 94] and the Lord of hosts (“Lord God of Sabaoth” in the older versions) were two ancient titles for the Lord, one linking him to the royal dynasty in Jerusalem and the other proclaiming him the ruler of the angel hosts.[ 95] A comparison of Isaiah 37:16 and 2 Kings 19:15, the Deuteronomic historian’s version of the same passage, shows that the title “Lord of hosts” has been removed by the disciple of the reformers.

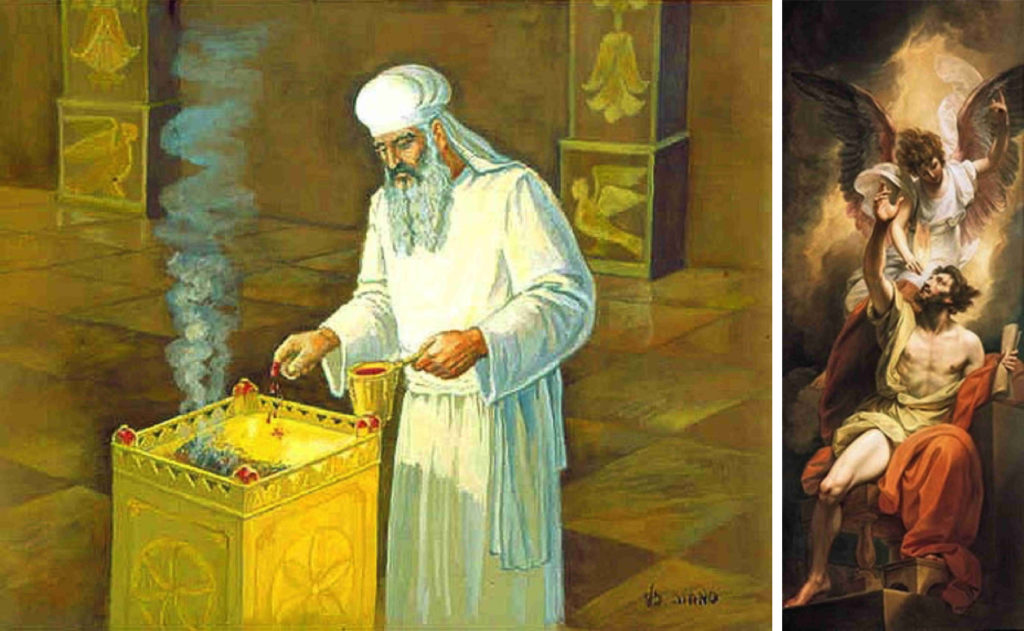

Figures 5a and 5b. Left: The high priest sprinkles blood on the altar of incense that stood before the veil

Right: Benjamin West (1738–1820): Isaiah’s Lips Anointed with Fire, after 1772.

6 Then flew one of the seraphims unto me, having a live coal in his hand, which he had taken with the tongs from off the altar:

7 And he laid it upon my mouth, and said, Lo, this hath touched thy lips; and thine iniquity is taken away, and thy sin purged.

Barker describes the scene as follows:[ 96]

One of the seraphim then picked up a coal from the incense altar and took away the guilt and sin from his lips.[ 97] This small altar inside the temple was used for incense offerings,[ 98] and so the heavenly and earthly temples coalesce.

Presumably the coal, “taken … off the altar”[ 99] of incense that “purged” (literally “atoned for”[ 100]) Isaiah’s sin previously had been sprinkled with sacrificial blood. Thus, symbolically, his lips had been sanctified by blood of Jesus Christ (who, arguably, may have been the very “one of the seraphims” mentioned in the verse), preparing him to speak with and for God.

It should be remembered, however, that being touched by the coals of the altar — like the application of the Savior’s Atonement that it represents — does not bring purity by a purely mechanical process. Rather, its effect depends on the state of the person or thing to which the coals are applied. In the case of the righteous Isaiah, the effect was a healing purging of sin. On the other hand, in Ezekiel’s vision of the angel who takes coals from the altar, they are used to burn up the wicked Jerusalem.[ 101] Likewise, in Revelation 8:5-13, the coals from the altar brought destruction throughout the earth.

8 Also I heard the voice of the Lord, saying, Whom shall I send, and who will go for us? Then said I, Here am I; send me.

Gileadi explains the significance of this verse:[ 102]

Now that Isaiah can again speak — and desiring to do for his people as has been done for him — he gladly accepts Jehovah’s prophetic commission to minister to his people. The verb “send” (salah) has the same Hebrew root as the noun “apostle” (saliah), signifying one who is “sent” to bear witness of what he has seen and heard.

In response to God’s call to sacrifice his son Isaac, Abraham had become the first Old Testament prophet known to have answered God with the words “Behold, here I am.”[ 103] Erich Auerbach observes that the reply is “not meant to indicate the actual place where Abraham is but a moral position in respect to God, who has called to him — Here am I awaiting thy command.”[ 104] Likewise, Richard D. Draper, S. Kent Brown, and Michael D. Rhodes note that the statement carries the implicit claim “that the speaker is in the right path.”[ 105] The symbolic purging of Isaiah’s lips is a witness that he is not only willing but fit to represent the Lord.

9 ¶ And he said, Go, and tell this people, Hear ye indeed, but understand not; and see ye indeed, but perceive not.

10 Make the heart of this people fat, and make their ears heavy, and shut their eyes; lest they see with their eyes, and hear with their ears, and understand with their heart, and convert, and be healed.

Go and tell this people. Gileadi draws out the meaning of this phrase:[ 106]

The verb “go” denotes Jehovah’s actual commission of Isaiah as His prophet. The terms “these people” or “this people” (ha’am hazzeh), however, reflects the people’s repudiation of their covenant relationship with Jehovah that is commonly expressed by the possessive “My people” (‘ammî). When they grow alienated, they see things their way, not His.[ 107] Hence the words, “Go on hearing, but not understanding; Go on seeing, but not perceiving.” As Jehovah forewarns, a wayward people’s typical response when a prophet appeals to them to repent is to harden their hearts and dull their senses.

Hear ye indeed, but understand not; and see ye indeed but perceive not. Translators have struggled to come up with a meaningful rendering of this message: e.g., “Keep listening, but do not comprehend; keep looking, but do not understand”;[ 108] “Hear, indeed, but do not understand; See, indeed, but do not grasp.”[ 109] The Book of Mormon reads it as: “Hear ye indeed, but they understood not; and see ye indeed, but they perceived not.”[ 110]

Make the heart of this people fat, and make their ears heavy, and shut their eyes. “Dull that people’s mind, Stop its ears, And seal its eyes.”[ 111]

Heschel eloquently describes the painful situation in which the prophet has been placed as the result of his commission:[ 112]

The mandate Isaiah received is fraught with an appalling contradiction. He is told to be a prophet in order to thwart and defeat the purpose of being a prophet. … It is generally assumed that the mission of a prophet is to open the people’s hearts, to enhance their understanding, and to bring about rather than to prevent their turning to God.

How can we reconcile the nature of such a commission with God’s relentless efforts elsewhere to persuade men to come unto [Him]”?[ 113] Heschel further explains:[ 114]

The haunting words which reached Isaiah seem not only to contain the intention to inflict insensitivity, but also to declare that the people already are afflicted by a lack of sensitivity. The punishment of spiritual deprivation will be but an intensification or an extension of what they themselves have done to their own souls.

Jesus drew on some of the same prophetic types as Isaiah to characterize His own ministry. For example, in Abraham 3:27, His response to the Father’s call parallels that of the prophet. Jesus also invoked the Lord’s commission to Isaiah to “shut their eyes” “lest they … be healed” in his explanation of why He spoke in parables[ 115] and why — despite the miracles He performed — he was not believed.[ 116] However, at first glance there seemed to be a difference in that at least His closest disciples were meant to understand His words, as Barker explains:[ 117]

The New Testament usage implies that only Jesus’ closest disciples were to understand the “secrets” of which he spoke and to see his glory. Perhaps there was something of this in the original; Isaiah 8:16 does speak of sealing the teaching among his disciples.

lest they … be healed. In short, “repentance is no longer an option.”[ 118] “The message God gives Isaiah will … lead to … the hardening of the people’s heart, thus making them ripe for God’s judgment.[ 119]

11 Then said I, Lord, how long? And he answered, Until the cities be wasted without inhabitant, and the houses without man, and the land be utterly desolate,

12 And the Lord have removed men far away, and there be a great forsaking in the midst of the land.

Gileadi comments as follows:[ 120]

Taken aback by the pessimistic prospect of his prophetic commission, Isaiah [asks] how long his ministry will last. Jehovah’s response illustrates the utter desolation his unrepentant people will experience when a full measure of covenant curses overtakes them. … When given a similar prophetic commission to warn Jehovah’s people, the servant meets with a similar response.[ 121]

Accordingly, “the divine judgment will involve the exile of most of the nation.”[ 122]

13 ¶ But yet in it shall be a tenth, and it shall return, and shall be eaten: as a teil tree, and as an oak, whose substance is in them, when they cast their leaves: so the holy seed shall be the substance thereof.

The Hebrew of this verse poses unsurmountable difficulties for Bible translators, who can only guess at its complete meaning. Unfortunately, the translation of the verse in 2 Nephi 16:13 does not shed significant light as it is similar in substance to the King James version. Here is Gileadi’s translation of the verse:[ 123]

And while yet a tenth [of the people] remains in it, or return, they shall be burned. But like the terebinth or the oak when it is felled, whose stump remains alive, so shall the holy offspring be what is left standing.

He explains the meaning of the verse as follows:

Using the imagery of tithing — in which the Israelites pay a tenth of the land’s yield to the Levites and the Levites pay a tenth of that tenth to the priests[ 124] — Isaiah contrasts the many who perish with the few who survive. The “holy offspring” left standing — a tenth of the tenth — compares to a terebinth or oak that can renew itself when cut down. The one who fells the tree is the king of Assyria/Babylon, Jehovah’s “axe” and “saw.”[ 125]

Figure 6. Isaiah’s Career, Sawed in Two at the End (Roda Bible)[126]

Ironically, according to tradition, Isaiah, the one who prophesied of axe and saw being applied to the Israelites, was himself martyred by being trapped in a tree and sawn in two.

The Why

Gileadi concludes with an observation that is as true and relevant today as it was in Isaiah’s time:[ 127]

“Seeing” with the eyes, “hearing” with the ears, “understanding” in the heart, and “repenting” at the same time constitutes Jehovah’s formula for “healing” or salvation. A remnant of Jehovah’s people — a “holy offspring”[ 128] comprised of those who repent — thus survives destruction in his Day of Judgment.

References

Alexander, P. "3 (Hebrew Apocalypse of) Enoch." In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. 2 vols. Vol. 1, 223-315. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Anderson, Gary A. The Genesis of Perfection: Adam and Eve in Jewish and Christian Imagination. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001.

Attridge, Harold W., Wayne A. Meeks, Jouette M. Bassler, Werner E. Lemke, Susan Niditch, and Eileen M. Schuller, eds. The HarperCollins Study Bible, Fully Revised and Updated Revised ed. New York City, NY: HarperOne, 2006.

Auerbach, Erich. 1946. Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature. Translated by Willard R. Trask. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013.

Barker, Margaret. "What did King Josiah reform?" In Glimpses of Lehi’s Jerusalem, edited by John W. Welch, David Rolph Seely and Jo Ann H. Seely, 523-42. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS) at Brigham Young University, 2004.

———. Christmas: The Original Story. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 2008.

Berlin, Adele, and Marc Zvi Brettler, eds. The Jewish Study Bible, Featuring the Jewish Publication Society TANAKH Translation. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. "The Ezekiel Mural at Dura Europos: A tangible witness of Philo’s Jewish mysteries?" BYU Studies 49, no. 1 (2010): 4-49.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and Ronan J. Head. "Mormonism’s Satan and the Tree of Life (Longer version of an invited presentation originally given at the 2009 Conference of the European Mormon Studies Association, Turin, Italy, 30-31 July 2009)." Element: A Journal of Mormon Philosophy and Theology 4, no. 2 (2010): 1-54.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. "The tree of knowledge as the veil of the sanctuary." In Ascending the Mountain of the Lord: Temple, Praise, and Worship in the Old Testament, edited by David Rolph Seely, Jeffrey R. Chadwick and Matthew J. Grey. The 42nd Annual Brigham Young University Sidney B. Sperry Symposium (26 October, 2013), 49-65. Provo and Salt Lake City, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University and Deseret Book, 2013.

———. Creation, Fall, and the Story of Adam and Eve. 2014 Updated ed. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014.

———. Temple Themes in the Book of Moses. 2014 update ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Publishing, 2014.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. "’He that thrusteth in his sickle with his might … bringeth salvation to his soul’: Doctrine and Covenants section 4 and the reward of consecrated service." In D&C 4: A Lifetime of Study in Discipleship, edited by Nick Galieti, 161-278. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2016.

———. "Faith, hope, and charity: The ‘three principal rounds’ of the ladder of heavenly ascent." In “To Seek the Law of the Lord”: Essays in Honor of John W. Welch, edited by Paul Y. Hoskisson and Daniel C. Peterson, 59-112. Orem, UT: The Interpreter Foundation, 2017.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and Matthew L. Bowen. "”By the Blood Ye Are Sanctified”: The Symbolic, Salvific, Interrelated, Additive, Retrospective, and Anticipatory Nature of the Ordinances of Spiritual Rebirth in John 3 and Moses 6." Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 24 (2017): 123-316. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/by-the-blood-ye-are-sanctified-the-symbolic-salvific-interrelated-additive-retrospective-and-anticipatory-nature-of-the-ordinances-of-spiritual-rebirth-in-john-3-and-moses-6/. (accessed January 10, 2018).

Charlesworth, James H. The Good and Evil Serpent: How a Universal Symbol Became Christianized. The Anchor Bible Reference Library, ed. John J. Collins. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010.

Draper, Richard D., S. Kent Brown, and Michael D. Rhodes. The Pearl of Great Price: A Verse-by-Verse Commentary. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005.

Dunn, James D. G., and John W. Rogerson. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2003.

Ephrem the Syrian. ca. 350-363. "The Hymns on Paradise." In Hymns on Paradise, edited by Sebastian Brock, 77-195. Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1990.

Fisch, Harold. The Biblical Presence in Shakespeare, Milton, and Blake: A Comparative Study. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press, 1999.

Fletcher-Louis, Crispin H. T. "Heavenly ascent and incarnational presence: A revisionist reading of the ‘Songs of the Sabbath Sacrifice’." In Society of Biblical Literature 1998 Seminar Papers. SBLSP 37, 367-99. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1998.

Freedman, H., and Maurice Simon, eds. 1939. Midrash Rabbah 3rd ed. 10 vols. London, England: Soncino Press, 1983.

Gee, John. "The keeper of the gate." In The Temple in Time and Eternity, edited by Donald W. Parry and Stephen D. Ricks. Temples Throughout the Ages 2, 233-73. Provo, UT: FARMS at Brigham Young University, 1999.

Gileadi, Avraham. The Apocalyptic Book of Isaiah: A New Translation with Interpretative Key. Provo, Utah: Hebraeus Press, 1982.

Goodenough, Erwin Ramsdell. Symbolism in the Dura Synagogue. 3 vols. Jewish Symbols in the Greco-Roman Period 9-11, Bollingen Series 37. New York City, NY: Pantheon Books, 1964.

Heschel, Abraham Joshua. 1962. The Prophets. Two Volumes in One ed. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2007.

Jensen, Jay E. "Spirit." In Encyclopedia of Mormonism, edited by Daniel H. Ludlow. 4 vols, 1403-05. New York City, NY: Macmillan, 1992. https://eom.byu.edu/index.php/Spirit. (accessed October 4, 2016).

Joines, Karen Randolph. "Winged serpents in Isaiah’s inaugural vision." Journal of Biblical Literature 86, no. 4 (1967): 410-15.

Kulik, Alexander. Retroverting Slavonic Pseudepigrapha: Toward the Original of the Apocalypse of Abraham. Text-Critical Studies 3, ed. James R. Adair, Jr. Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature, 2004.

Newsom, Carol. Songs of the Sabbath Sacrifice: A Critical Edition. Harvard Semitic Studies 27. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1985.

Nibley, Hugh W. 1975. The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment. 2nd ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005.

Nickelsburg, George W. E., ed. 1 Enoch 1: A Commentary on the Book of 1 Enoch, Chapters 1-36; 81-108. Hermeneia: A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2001.

Nickelsburg, George W. E., and James C. VanderKam, eds. 1 Enoch 2: A Commentary on the Book of 1 Enoch, Chapters 37-82. Hermeneia: A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2012.

Origen. ca. 200-230. "De Principiis." In The Ante-Nicene Fathers (The Writings of the Fathers Down to AD 325), edited by Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson. 10 vols. Vol. 4, 239-384. Buffalo, NY: The Christian Literature Company, 1885. Reprint, Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2004.

Parry, Donald W. "Garden of Eden: Prototype sanctuary." In Temples of the Ancient World, edited by Donald W. Parry, 126-51. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1994.

Philo. b. 20 BCE. "On the Virtues (De Virtutibus)." In Philo, edited by F. H. Colson. 12 vols. Vol. 8. Translated by F. H. Colson. The Loeb Classical Library 341, 158-305, 440-50. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1939.

———. b. 20 BCE. "On the Confusion of Tongues (De Confusione Linguarum)." In The Works of Philo: Complete and Unabridged, edited by C. D. Yonge. New Updated ed. Translated by C. D. Yonge, 234-52. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2006.

Rubinkiewicz, R. "Apocalypse of Abraham." In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. 2 vols. Vol. 1, 681-705. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Sandmel, Samuel, M. Jack Suggs, and Arnold J. Tkacik. "Ecclesiasticus or The Wisdom of Jesus Son of Sirach." In The New English Bible with the Apocrypha, Oxford Study Edition, edited by Samuel Sandmel, M. Jack Suggs and Arnold J. Tkacik, 115-75. New York City, NY: Oxford University Press, 1976.

Scholem, Gershom, ed. 1941. Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism. New York City, NY: Schocken Books, 1995.

Stone, Michael E. "The fall of Satan and Adam’s penance: Three notes on the Books of Adam and Eve." In Literature on Adam and Eve: Collected Essays, edited by Gary A. Anderson, Michael E. Stone and Johannes Tromp, 43-56. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2000.

Thomas, M. Catherine. "Women, priesthood, and the at-one-ment." In Spiritual Lightening: How the Power of the Gospel Can Enlighten Minds and Lighten Burdens, edited by M. Catherine Thomas, 47-58. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1996.

Tvedtnes, John A. "Priestly clothing in Bible times." In Temples of the Ancient World, edited by Donald W. Parry, 649-704. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1994.

von Wellnitz, Marcus. "The Catholic Liturgy and the Mormon temple." BYU Studies 21, no. 1 (1979): 3-35.

Young, Brigham. 1853. "Necessity of building temples; the endowment (Oration delivered in the South-East Cornerstone of the Temple at Great Salt Lake City, after the First Presidency and the Patriarch had laid the Stone, 6 April 1853)." In Journal of Discourses. 26 vols. Vol. 2, 29-33. Liverpool and London, England: Latter-day Saints Book Depot, 1853-1886. Reprint, Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1966.

Endnotes

When Isaiah saw the throne, the hem of the Lord’s robe filled the temple. Later tradition associated the robe of God with his entourage, the heavenly host, and it may be that the more ambiguous “train” better captures the sense of the vision; “His train,” that is, his attendants, “filled the temple.” The Targum of Isaiah and the LXX say that the temple was filled with his glory; again, later tradition found in Philo (Philo, Tongues, 171) shows that the visible glory of the Lord was the angels who filled the created order, and since the hekal (nave) of the temple represented the created order, we see here that the Septuagint is quite consistent with what is known of temple imagery in a later period. The cherubim depicted on the walls of the temple (2 Chronicles 3:7) became the heavenly host.

Ezekiel 1 and Revelation 4:6–9 describe beings with a similar function. Charlesworth comments: “The seraphim have wings, faces, feet, and human features; these characteristics have confused some scholars who assume they thus cannot be serpents. Near Eastern iconography … is replete with images of serpents with faces, feet, wings, and human features” (ibid., p. 444).

The only explicit references in the Bible to seraphim in the Holy of Holies are in Isaiah 6:2, 6. However, Nickelsburg suggests, based on a midrash on Genesis 3:24 that cites Psalm 104:4 H. Freedman et al., Midrash, 1:178) that the “flaming sword” of Genesis 3:24 (Moses 4:31) might be associated more correctly with seraphim rather than cherubim G. W. E. Nickelsburg, 1 Enoch 1, p. 296 n. 7).

He also sees the “those who were there … like a flaming fire” in 1 Enoch 17:1 and the “serpents” of 1 Enoch 20:7 as good candidates for the appellation of seraphim (ibid., 17:1 p. 276; 20:7, p. 294).

Of course, the serpent is an ambivalent symbol, as James H. Charlesworth captured in the title of his book The Good and Evil Serpent (J. H. Charlesworth, Serpent). Not only does the serpent sometimes represent evil, it also impersonates the good, as it apparently did in the Garden of Eden (J. M. Bradshaw et al., Mormonism’s Satan, pp. 18–19):

Of great significance here is the fact that the serpent is a frequently used symbol of life-giving power (Numbers 21:8–9; John 3:14–15; 2 Nephi 25:20; Alma 33:19; Helaman 8:14–15). In the context of the temptation of Eve, LDS scholars Draper, Brown, and Rhodes conclude that Satan “has effectively come as the Messiah, offering a promise that only the Messiah can offer, for it is the Messiah who will control the powers of life and death and can promise life, not Satan” R. D. Draper et al., Commentary, p. 43. See John 5:25–26; 2 Nephi 9:3–26).

Not only has the Devil come in guise of the Holy One, he seems to have deliberately appeared, without authorization, at a most sacred place in the Garden of Eden ibid., pp. 42, 150–151). Indeed, if it is true, as Ephrem the Syrian believed, that the Tree of Knowledge was a figure for “the veil for the sanctuary” Ephrem the Syrian, Paradise, 3:5, p. 92. See also J. M. Bradshaw, Tree of Knowledge), then Satan has positioned himself, in the extreme of sacrilegious effrontery, as the very “keeper of the gate” (2 Nephi 9:41. Compare 2 Thessalonians 2:3–4) to the Tree of Life — symbolizing the possibility, under proper circumstances, of “exaltation” in Mormon language. Thus, it seems, Eve’s deception consisted in having taken the forbidden fruit “from the wrong hand, having listened to the wrong voice” M. C. Thomas, Women, p. 53).

On Jesus as the “better of all the seraphim,” see Hebrews 1:3–8, where He is described as the greatest of the divine attendants of the Father — specifically as the “brightness of [God’s] glory, and the express image of his person,” sitting nearer to the throne than any of the seraphim, i.e., “on the right hand of the Majesty on high,” and, in explicit terms, as having been “made so much better than the angels” (see vv. 3–4). Barker adds this interesting reference: “Origen, a Christian biblical scholar in the first half of the third century ad, said that the two angel figures of the vision were the Son of God and the Holy Spirit, an interpretation which he claimed to have learned from a rabbi” (Margaret Barker, Isaiah, in J. D. G. Dunn et al., Eerdmans Commentary. See Origen, De Principiis, 1.3.4).

In LDS theology and scripture, angels are not typically understood as beings of a different race than man. Although “Latter-day revelation has not identified or clarified the nature of seraphim or cherubim mentioned in the Bible” (J. E. Jensen, Spirit), the argument of Hebrews 1 is that although the angels spoken of resemble in their various honors God’s preeminent Son, He, through the accomplishment of His unique mission as Savior and Redeemer, has “by inheritance obtained a more excellent name than they” (Hebrews 1:4).

Of course, sometimes an equivalent reply can be given using different words. For example, the reply of Mary in Luke 1:38 certainly is made in the same spirit as Abraham’s reply: “Behold the handmaid of the Lord; be it unto me according to thy word.”