Part 1 ⎜ Part 2 ⎜ Part 3 | Part 4 ⎜ Part 5 ⎜ Part 6 ⎜ Part 7 ⎜ Part 8 ⎜ Part 9

For more information on the book, visit https://interpreterfoundation.org/books/

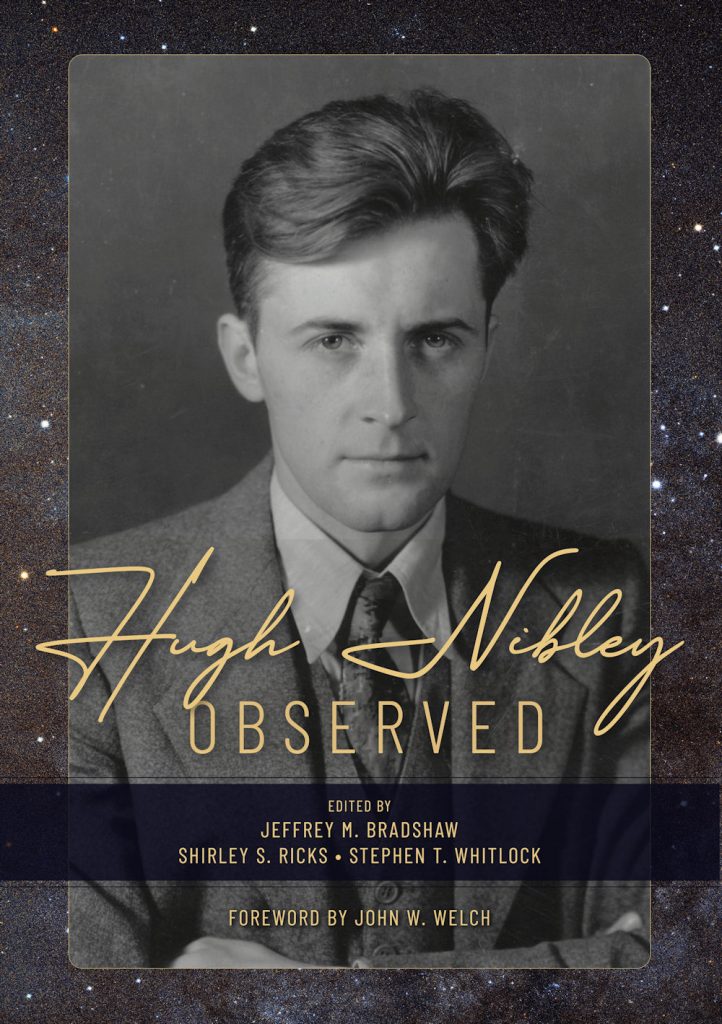

This is the fourth of eight weekly blog posts published in honor of the life and work of Hugh Nibley (1910–2005). The series is in honor of the new, landmark book, Hugh Nibley Observed, available in softcover, hardback, digital, and audio editions. Each week our post is accompanied by interviews and insights in pdf, audio, and video formats. (See the links at the end of this post.)

In line with Nibley’s description of the Pearl of Great Price, we borrow a chapter title from Boyd Jay Petersen’s wonderful biography on Hugh Nibley as the theme of this week’s Insight: “The Book That Answers All the Questions.”[1]

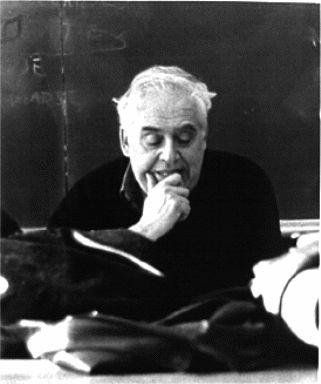

Harold Bloom, 1930-2019

The eminent Yale professor and Jewish literary scholar Harold Bloom, described in 2017 by Oxford Bibliographies as “probably the most famous literary critic in the English-speaking world,”[2] called the Book of Moses and the Book of Abraham two of the “more surprising” and “neglected” works of Latter-day Saint scripture.[3] With the great spate of publications over the decades since fragments of Egyptian papyri were rediscovered in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, we have begun to see a remedy for the previous neglect of the Book of Abraham. Now, gratefully, because of wider availability of the original manuscripts and new detailed studies of their contents, the Book of Moses is also beginning to receive its due. In fact, this coming Friday and Saturday, April 23–24, 2021, the Interpreter Foundation, BYU Ancient Scripture, Book of Mormon Central, and FAIR will host the second of two groundbreaking conferences on the theme of “Tracing Ancient Threads in the Book of Moses” ( https://interpreterfoundation.org/conferences/2021-book-of-moses-conference/ ).

What did Professor Bloom find so “surprising” in the Book of Moses? He said he was intrigued by the fact that many of its themes are “strikingly akin to ancient suggestions.” While expressing “no judgment, one way or the other, upon the authenticity” of Latter-day Saint scripture, he found “enormous validity” in the way these writings “recapture … crucial elements in the archaic Jewish religion … that had ceased to be available either to normative Judaism or to Christianity, and that survived only in esoteric traditions unlikely to have touched [Joseph] Smith directly.”[4] In other words, Professor Bloom found it a great wonder that Joseph Smith could have come up with, on his own, a modern book that resembles so closely ancient Jewish and Christian teachings. Not surprisingly, Gary Gillum noted that three heavily annotated copies of a talk by Harold Bloom on Joseph Smith were found among Nibley’s papers after his passing.[5]

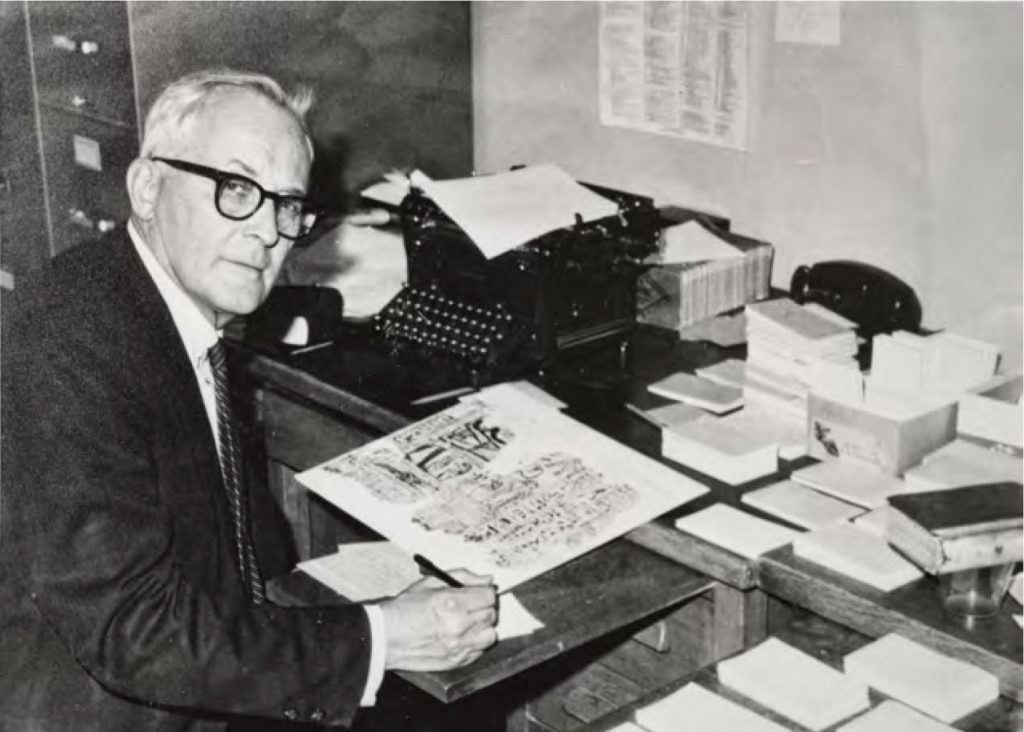

Hugh looks over a reproduction of Facsimile 1 from the Joseph Smith Papyri, ca. 1967, his desk covered by stacks of his trademark notecards.”[6]

Like Professor Bloom, Hugh Nibley had glowing assessment of the Pearl of Great Price. Comparing the different volumes of scripture in the Latter-day Saint canon, he wrote:[7]

The Book of Mormon and the Old Testament are tribal histories — we still identify ourselves with the tribes of Israel. The New Testament and the Doctrine and Covenants are theological and doctrinal teachings, everlasting and timeless. But the Pearl of Great Price brings together the contemporary accounts of the seven main dispensations of the world since Adam. Coming last, it sums up the entire history of mankind, filling in many of the gaps in our knowledge that have remained to this day. The records of Adam, Enoch, Noah, Abraham, Moses, and Joseph Smith were given to the Saints as a bonus for their acceptance of the Book of Mormon and are still kept in reserve; we may anticipate the pleasure of more light to come.

Because the subject of this week’s Insight essay, video, and podcast is the Book of Moses, we will focus below on Nibley’s involvement with the Book of Abraham.

To undertake serious study of the Book of Abraham, Nibley realized he would have to learn Egyptian. In Hugh Nibley Observed he relates how he got started with the language during a sabbatical at Berkeley:[8]

Along with teaching I sweated for a year at Egyptian and Coptic with a very able and eager young professor.[9] The Coptic would be useful, but Egyptian? At my age? As soon as I got back to Provo I found out. … Then in 1966 I studied more Egyptian in Chicago, thanks to the kind indulgence of Professors Baer and Wilson, but still wondered if it was worth all the fuss. When lo, in the following year came some of the original Joseph Smith Papyri into the hands of the Church; our own people saw in them only a useful public relations gimmick, but for the opposition they offered the perfect means of demolishing Smith once and for all.

In BYU professor Michael D. Rhodes’ chapter in Hugh Nibley Observed, he says more about the finding of the papyri and its significance in Nibley’s work for years to come:[10]

On November 27, 1967, the Metropolitan Museum of Art formally gave the Joseph Smith Papyri fragments to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The Church then published photos of the papyri in the February 1968 Improvement Era. This was a remarkable feat, since at that time, it took two full months to publish talks from general conference, which we now can get online the next day. Nibley had been given access to the papyri, and he began an in-depth study of them. Nibley’s work on the Joseph Smith Papyri and the Book of Abraham covered more than forty years and resulted in four books and numerous articles and talks.

While BYU professor John Gee was well aware that Nibley’s approach to Egyptology had both strengths and weaknesses, he admired Nibley’s willingness to dive into such daunting research headlong. Gee recalled Nibley’s list of four options available to Latter-day Saint scholars in the face of the opportunities and challenges afforded by the newly discovered papyri:[11]

- We can ignore them. …

- We can run away from them. …

- We can agree with the world. …

- Finally, we can meet the opposition on their own grounds.

According to Gee, “Nibley followed the last of the options that he laid out. Even more than half a century later, Nibley’s observations are still on target and as relevant as ever.”[12]

Nibley was determined to finish a final book relating to the Book of Abraham, entitled One Eternal Round, and worked diligently on it for more than fifteen years. However, the work was uncompleted when Nibley suffered his final illness at age 94. Michael Rhodes recounts the dilemma that faced a small group of Nibley’s friends as they met in his home to decide what to do about the manuscript. Nibley himself was present in a hospital bed, asleep or unconscious:[13]

A few months before, a group of us had gone to the upper story of his home to collect all of Hugh’s materials relating to this book that were scattered in several different rooms. This comprised over thirty boxes of papers, notes, and pictures, as well as some 450 computer files that contained sometimes as many as twenty different versions of a given chapter. This was a huge amount of material. How could we take all this and make a book out of it? …

It became clear that the only practical way to do this would be for one person to simply immerse himself in this massive collection of material and condense and distill it into publishable form. This would require much more than simple editing, and the person would have to be a coauthor because there were many parts that were still incomplete. As we all looked uncomfortably at each other, no one at that point was willing to commit to doing it. So we adjourned without making a final decision. The rest of that day, I almost felt what Alma describes as “suffering the pains of a damned soul” (Alma 35:16). I kept going over and over in my mind, thinking, “Mike, you’ve got to do this for Hugh.” That night, I lay awake, still struggling with the magnitude of the task and whether I could even accomplish it. Finally, sometime in the middle of the night, a sense of calm came over me, and I realized this was something I had to do and could do. I would finish this book for Hugh. I owed him so much because of all the things he had done for me over the years.

So, the next morning I called Shirley Ricks to tell her I’d be willing to finish the book. … I was doing a couple of other things in my office … when the phone rang. It was Shirley saying that Hugh had passed away earlier that morning. I firmly believe that once I had made that decision, Hugh somehow knew it and felt he could then leave this life assured that his book would be finished.

Before closing, I would like to focus on a statement by Gary Gillum: “Infinitely more important than Nibley’s scholarship, talents, and gifts was the man himself.”[14] There are many reasons why this statement is true, but an incident related by Sterling J. Albrecht is revealing about Nibley’s personal priorities:[15]

Hugh and I were invited to [Salt Lake City] to pick up the [newly rediscovered Joseph Smith] Papyri. We met with Elder Tanner [counselor to President David O. McKay] in his office. He told us that the First Presidency was sending the Papyri to BYU so that Hugh could study and interpret it. He also said that the Papyri was very valuable and if anything happened … [while we were driving] that Hugh and I should just keep going. As we were driving to Provo, we saw two ladies at the side of the road with the hood of their car up. I thought that we should stop but also remembered Elder Tanner’s admonition that we had very valuable cargo, so I was going to drive on by. Hugh said, “Stop the car, they need help!” We stopped, locked the car and walked over to see if we could help the women. They said that the car would start but they couldn’t get the hood down so that they could drive it. Hugh got up on the top of the car, hung his feet down over the windshield, and then pushed on the hood with both of his feet. He forced the hood down and the ladies were able to drive it.

Such stories reveal the real Hugh Nibley.

A Conversation about Hugh Nibley with Stephen T. Whitlock

We hope you will enjoy the video interview of Stephen T. Whitlock embedded here, which you can view in either long or short form. Steve shares his experiences as an editor for Hugh Nibley Observed as well as describing Nibley’s impact on his personal life.

What Did Enoch Scholar Matthew Black Say To Hugh Nibley about the Book of Moses Enoch Account?

In addition, this week’s Insight media outlines one of Hugh Nibley’s discoveries about the Book of Moses. A short video entitled “What Did Enoch Scholar Matthew Black Say To Hugh Nibley about the Book of Moses Enoch Account?” is embedded below, along with a longer podcast and pdf transcript that are available for listening or download.

Listen to the complete audio recording of “What Did Enoch Scholar Matthew Black Say To Hugh Nibley about the Book of Moses Enoch Account?”:

Finally, don’t forget to check out the program for the April 23–24 conference on “Tracing Ancient Threads in the Book of Moses” (https://interpreterfoundation.org/conferences/2021-book-of-moses-conference/).

References

Bloom, Harold. The American Religion: The Emergence of the Post-Christian Nation. New York City, NY: Simon and Schuster, 1992.

———. Jesus and Yahweh: The Names Divine. New York City, NY: Riverhead Books (Penguin Group), 2005.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., Shirley S. Ricks, and Stephen T. Whitlock, eds. Hugh Nibley Observed. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2021.

Nibley, Hugh W., and Michael D. Rhodes. One Eternal Round. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 19. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2010.

Petersen, Boyd Jay. Hugh Nibley: A Consecrated Life. Draper, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2002.

I’ve seen various references to Hugh Nibley’s collection of 3×5 cards, but they give only a vague idea about what was on these cards and how he used them. Does anyone know what all those boxes of cards were for?