An Old Testament KnoWhy[1]

relating to the reading assignment for

Gospel Doctrine Lesson 29:

“He Took Up … the mantle of Elijah” (2 Kings 2:5-6)

(JBOTL29B)

Figure 1. Cornelis Engelbrechtsen (1468-1533): Triptych of the Cleansing of Naaman: the center panel depicts Naaman, commander of the Syrian army, washing in the River Jordan to cure his leprosy at the command of the prophet Elisha, who in the background refuses gifts offered to him, 1520

Question: Elisha’s request of Naaman to immerse himself seven times in the Jordan River in order to be healed[2] and his “stretching himself” upon a child to raise him from the dead[3] seem highly unusual. Was there any special meaning to Elisha’s actions?

Summary: Like some other Old Testament prophets, Elisha’s invocation of God’s power as he taught and blessed his people was accompanied by actions that symbolized sacred realities. As with modern priesthood ordinances, the physical actions themselves do not bring about the resultant blessings. However, such sacred actions, when required by the Lord, invite participants to reflect about resonances of those actions that extend beyond immediate circumstances and teach eternal principles. Symbolic actions that parallel Elisha’s miracles has at times accompanied healing both anciently and today.

The Know

In this article, I will summarize the practice of immersion to effect healing in the story of Naaman and in modern times. This will be followed by a discussion of the symbolism involved in Elisha’s actions in raising of a child from the dead and of its ancient and modern parallels.

Symbolism in the Practice of Immersion for Healing

Few stories of Old Testament prophets are better known among the Latter-day Saints than that of the healing of Naaman the Syrian after he followed the instructions of the prophet Elisha:[4]

Then went [Naaman] down, and dipped himself seven times in Jordan, according to the saying of the man of God [Elisha]: and his flesh came again like unto the flesh of a little child, and he was clean.

Members of the Church are familiar with the common application of the story to the requirement of faith to follow difficult-to-understand instructions from modern Church leaders. Parallels to the symbolism of baptism have also been noted. For example, Travis T. Anderson has written:[5]

Conversion to Christ and baptism by immersion free us from the shadow of spiritual death, leaving us, like Naaman, clean as a little child.

The Old Testament story of Naaman’s cleansing from leprosy serves as a wonderful symbol of the baptism of repentance taught in the New Testament. It illustrates both the relation of many Old Testament events to New Testament teachings and the overarching unity of the two works that can be seen when viewed from a perspective that Naaman lacked — an understanding of the plan of salvation and its requisite Messianic atonement.

Less-well-known to many modern Latter-day Saints is that rebaptism for renewal of baptismal covenants or for healing was often practiced in the restored Church from the Nauvoo period and into the early 20th century. Jonathan A. Stapley summarized:[6]

In Nauvoo, Joseph Smith envisioned the temple to be a sacred place for healing. Not only was anointing a commonality between the temple rites and healing rites — from the first formal day of baptisms in the Nauvoo Temple font, people were also baptized for their health, a practice that was soon common outside the temple. In addition, the initiatory rituals of the Nauvoo Temple liturgy were also adapted to healing, as was the prayer circle.[7] Thus almost every aspect of the temple rites had a healing analogue.

Stapley also noted that “Joseph Smith led out in example. He baptized his wife Emma Smith for her health when she was sick, as well as a young girl in his care.”[8] Counseling the Nauvoo Saints on the practice, the Prophet wrote: “Baptisms for the dead, and for the healing of the body must be in the [temple] font, those coming into the Church, and those re-baptized [to renew their baptismal covenants] may be baptized in the river.”[9]

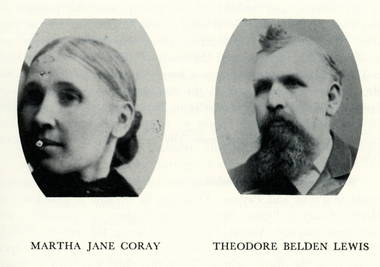

Figure 2. Martha Jane Knowlton Coray (June 3, 1821 – December 14, 1881)

Martha Jane Knowlton Coray (1821-1881) — a school teacher and the secretary to the Female Relief Society in Nauvoo, the only female member of the first Board of Trustees of Brigham Young Academy in Utah, and the mother of twelve children — is best known for the pains that she took, with the assistance of her husband Howard, to record Lucy Mack Smith’s dictations of the history of her family.[10] Howard wrote the following in his autobiography:[11]

Sometime in the winter following [the martyrdom], Mother Smith came to see my wife about getting her to write the history of Joseph, to act in the matter only as her, Mother Smith’s, amanuensis. This my wife was persuaded to do and so dropped the school.

According to family accounts, Martha would take their little two-year-old son Howard and their baby daughter, nine-month-old Martha Jane (Little Martha),[12] with her every day as she took dictation from Mother Smith. On one tragic day:[13]

the baby, Little Martha, accidentally fell down some steps and lost her sight. Now the baby who was showing such strides in crawling around could only grope and cry with an outstretched arm for help. It became necessary for Martha Jane to spend more time with Little Martha but she felt the need to carry on with Mother Smith’s book. So, they took the problem to Brother Brigham.

Brigham was a leader of action and quick decision. [He] came to them and said, “Brother Coray, I know your heart is with the school, but I can’t find anyone that could help your wife as much as you can. Will you help her? I promise you that as you do, you will feel the Lord’s approval and gain His blessing in your life. Howard responded, “I’ll do the best I can.” Martha and Howard continued for a year to complete Joseph’s history. …

[After tensions reached the breaking point in Nauvoo, Martha and Howard] were able to leave with the majority of the Saints in May of 1846. They had hoped and prayed that Little Martha’s eyes could be healed before the trek, for her own ease and safety. She was now walking and able to grope her way around the house, but walking numerous miles blind and being around campsites would be very dangerous. Her older brother was assigned to hold her hand or walk right beside her whenever Howard or Martha couldn’t.

Figure 3. Martha Jane Coray and her husband Theodore Belden Lewis

[Delays plagued the Coray’s completion of the trek to the Salt Lake Valley.] Little Howard was approaching eight years old so Martha Jane had been taking evenings to discuss with the children about baptism, the Gift of the Holy Ghost and gifts of the Spirit. Howard gave both Little Howard and Little Martha a father’s blessing. Martha Jane felt a confirming heavenly spirit with the family that summer.

One day in late July she saw Howard coming from the field so she walked out to meet him. His first words were, “Something strange happened to me today. I always pray for guidance and for my family. But, today I had the distinct impression that if I immerse Little Martha in a running stream once each morning for seven mornings she will regain her sight. I didn’t hear anything. I didn’t see anything. It was just a rather small but clear impression.” Martha reminded him of the sweet spirit that had been with the family these past weeks and said, “We must do it.” “Yes, I feel we must,” said Howard, “and so we shall. I will make a partial dam in the creek tonight and it will be deep enough by morning.” It was a tender family experience, the next morning after a simple truthful explanation, the children and parents went in the fields to the little creek. Five-year-old Martha was not afraid for she was in the care of those she loved. She held tightly to Papa’s arm and did as he instructed. She was lowered into the cool water for just a few moments and then brought up again. Afterward she was dried and dressed by a loving mother. This ritual took place every day. On the sixth day, after the immersion Martha Jane hugged her husband, regardless of his wet clothes.

“Tomorrow,” was all she said. On the seventh day, the brightness of hope held them all in silence, A sweet child’s voice whispered, “Mama, this is the last day.” Her mother held her tight before she went into the water. Howard’s eyes were wet and his arms trembled but his voice was clear and confident. As the little girl came up from the immersion, her father lifted her into his arms and carried her toward her mother. Cradled in his arms, her face turned upward. She cried out, “The clouds, the clouds, they are fluffy pillows.” Her father stopped and fell to his knees. The child ran to her mother, “Mamma, Mamma, I see you.” Her little hands were still feeling as usual. “I see the baby. She looks like I knew she would look. Mamma, why are you crying, why are you kneeling, what are you saying? Are you praying? My brother, my brother, I see you. You won’t have to lead me anymore. Jesus has made me see.” …

How grateful Martha and Howard were that they had followed this quiet but clear prompting from the Lord. This they had done before but here committed to do more faithfully from that day on.

Symbolism in the Sacred Embrace

Figure 4. Pompeo Batoni, 1708-1787: The Return of the Prodigal Son, 1773

Another ancient symbol of renewed life is the sacred embrace.[14] Hugh Nibley notes that according to the Manichaean religion, “the right hand was used for bidding farewell to our heavenly parents upon leaving our primeval home and [was] the greeting with which we shall be received when we return to it.”[15] Likewise, the Mandaeans, whose history may intersect with disciples of John the Baptist,[16] still continue a ritual practice in which the kushta, a ceremonial handclasp, is given three times, each one of which, according to Elizabeth Drower, “seems to mark the completion … of a stage in a ceremony.”[17] At the moment of glorious resurrection, Mandaean scripture records that a final kushta will also take place, albeit in the form of an embrace — what the Ginza calls the “key of the kushta of both arms.” In this context, the two-armed embrace of Mandaean ritual can be seen as an intensification and a fulfillment of the handclasp gesture.

Both the handclasp and the sacred embrace may represent not only mutual love and trust but also a transfer of life and power from one individual to another. In what Elder Willard Richards called “the sweetest sermon from Joseph he ever heard in his life,”[18] the Prophet described a vision of the resurrection that, like Mandaean ritual, included a handclasp and an embrace:[19]

So plain was the vision. I actually saw men, before they had ascended from the tomb, as though they were getting up slowly. They took each other by the hand, and it was, “My father and my son, my mother and my daughter, my brother and my sister.” When the voice calls for the dead to arise, suppose I am laid by the side of my father, what would be the first joy of my heart? Where is my father, my mother my sister? They are by my side. I embrace them, and they me.

Joseph Smith’s words about the gesture of embrace in the resurrection recalls similar symbolism in the stories of Elijah and Elisha, who each employed a similar ritual gesture as they raised a dead child back to life.[20] The more detailed account of Elisha reads as follows (see Figure 5):[21]

Figure 5. Frederic Leighton, 1830-1896: Elisha Raising the Son of the Shunamite, 1881

And he [Elisha] went up, and lay upon the child, and put his mouth upon his mouth, and his eyes upon his eyes, and his hands upon his hands: and he stretched himself upon the child;[22] and the flesh of the child waxed warm.[23]

Figure 6. Frank Wesley, 1923-2002: The Forgiving Father, ca. 1954-195

Although some might take the “intent of this physical contact [as] to transfer the bodily warmth and stimulation of the prophet to the child, Elijah’s prayer, however, makes it clear that he expected the life of the child to return as an answer to prayer, not as a result of bodily contact.”[24] The threefold repetition of the act in the story of Elijah points to a ritual context,[25] perhaps corresponding to a similar Mesopotamian procedure where “the healer superimpose[s] his body over that of the patient, head to head, hand to hand, foot to foot.”[26]

In addition to the stories of Elijah and Elisha, Eugene Seaich noted the following parallels in Jewish and Christian sources:[27]

The same embrace reappeared in the early Christian Gospel of Thomas, where Jesus tells the disciples that they must “become one” with him by placing eyes in the place of an eye, and a hand in the place of a hand, and a foot in the place of a foot, and an image in the place of an image.[28]

That this was remembered even during the Middle Ages is shown by the fact that the Seder Eliyahu Rabbah (eighth century) also explains how God will resuscitate the dead by lifting them out of the dust, setting them on their feet, and placing them between his knees to embrace them and press them to him. … Compare Acts 20:10, where Paul raises a man from the dead with a sacred embrace. Also the Jewish apocryphon, Joseph and Aseneth, where Joseph gives his bride eternal life with an embrace and a kiss.[29]

Seeing anticipatory symbolism in this story, the Seder Eliyahu Rabbah specifically adds that the Messiah will be the very “Son of the Widow” whom Elijah raised from the dead.[30]

Figure 7. Pietro Lorenzetti, ca. 1280-1348: Deposition of Christ from the Cross, Lower Basilica of San Francesco d’Assisi, ca. 1320.[31]

There is also a symbolism of the sacred embrace in the miracles, death, and resurrection of the Savior. According to H. Riesenfeld,[32] whose careful study of Old Testament incidents of raising the dead showed detailed parallels to the later miracles of the Savior: “It is perhaps more than chance that the miracles of revivication performed, according to Jewish belief, by Elijah, Elisha, and Ezekiel, each prefiguring the coming Messiah, in some way have reached fulfillment in the Messianic activity of Jesus Christ.” According to Sparks and Gilquist, the actions of Elijah in reviving a dead child can also be seen as pointing forward to the “death, burial, and resurrection of Christ.”[33] Matthew Brown brought attention to Medieval paintings such as this one by Lorenzetti (Figure 7) that echo the actions of Elijah and Elisha, showing specific points of contact with the Savior at his death — face, hand, knee, and foot — with an embrace across the chest. Brown correlated such scenes with passages such as these from English mystery plays: “Behold my body … / And therefore thou shalt understand / In body, head, feet, and hand.”[34]

The Why

Specific gestures have been divinely prescribed for each priesthood ordinance. While the form of baptism recalls the symbolism of death and resurrection, the laying of hands on the head[35] that is used in confirmation suggests a retrospective regard toward the scriptural account of the creation of Adam wherein God “breathed into his nostrils the breath of life.”[36] In this respect, recall also the account in John 20:22, when Jesus “breathed on [His disciples], and saith unto them, Receive ye the Holy Ghost.” As Joseph Smith highlighted the importance of the manner in which baptism is performed, describing it as a “sign,” so did he refer to the symbolic evocation of the breath of life in “the laying on of hands,” by which the Holy Ghost is given, ordinations are performed, and the sick are healed, as a “sign.” He said pointedly that if such ordinances were not performed in the way God had appointed they “would fail.”[37]

Despite the relative consistency of ordinances over time, D&C 1:24 explicitly recognizes the need for bounded flexibility in adapting divine communication through words and symbols to accommodate mortal limitations, asserting that God always speaks to humans “in their weakness,” choosing a language of revelation that is “after the manner of their language, that they might come to understanding.” For example, Elder Bruce R. McConkie noted that three different ordinances — baptism, the sacrament, and animal sacrifice — were instituted at different times, using different tangible symbols, and in different types of settings, but all in association with one and the same covenant.[38] Though these three ordinances vary significantly in their expressions of relevant symbolism, each of them “is performed in similitude of the atoning sacrifice by which salvation comes.”[39]

What is important in all ordinances, including temple ordinances, is that any adaptations to different times, cultures, and practical circumstances be done under prophetic authority in order to minimize the possibility of changes that alter them in crucial ways.

Thanks to Kari Maxwell for sharing the manuscript of the unpublished family account entitled “One Seven-Dip Saint” for use in this article.

References

Anderson, Travis T. "Naaman, baptism, and cleansing." Ensign 24, January 1994. https://churchofjesuschrist.org/ensign/1994/01/naaman-baptism-and-cleansing?lang=eng. (accessed August 8, 2018).

Attridge, Harold W., Wayne A. Meeks, Jouette M. Bassler, Werner E. Lemke, Susan Niditch, and Eileen M. Schuller, eds. The HarperCollins Study Bible, Fully Revised and Updated Revised ed. New York City, NY: HarperOne, 2006.

Barker, Kenneth L., Donald Burdick, John Stek, Walter Wessel, Ronald F. Youngblood, and Kenneth Boa, eds. NASB Study Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1999.

Berlin, Adele, and Marc Zvi Brettler, eds. The Jewish Study Bible, Featuring the Jewish Publication Society TANAKH Translation. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. Creation, Fall, and the Story of Adam and Eve. 2014 Updated ed. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014.

———. "What did Joseph Smith know about modern temple ordinances by 1836?”." In The Temple: Ancient and Restored. Proceedings of the 2014 Temple on Mount Zion Symposium, edited by Stephen D. Ricks and Donald W. Parry. Temple on Mount Zion 3, 1-144. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2016.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and Matthew L. Bowen. "”By the Blood Ye Are Sanctified”: The Symbolic, Salvific, Interrelated, Additive, Retrospective, and Anticipatory Nature of the Ordinances of Spiritual Rebirth in John 3 and Moses 6." Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 24 (2017): 123-316. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/by-the-blood-ye-are-sanctified-the-symbolic-salvific-interrelated-additive-retrospective-and-anticipatory-nature-of-the-ordinances-of-spiritual-rebirth-in-john-3-and-moses-6/. (accessed January 10, 2018).

Brown, Matthew B. E-mail message to George L. Mitton, 16 November 2010, 2010.

Burchard, C. "Joseph and Aseneth." In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. Vol. 2, 177-247. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Cogan, Mordechai, and Hayim Tadmor. 2 Kings: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. The Anchor Bible 11, ed. William F. Albright and David Noel Freedman. New York City, NY: Doubleday, 1988.

Coray, Howard. n.d. Excerpts from the Autobiography of Howard Coray. In Book of Abraham Project. http://www.boap.org/LDS/Early-Saints/HCoray.html. (accessed August 9, 2018).

Drower, E. S. Water into Wine: A Study of Ritual Idiom in the Middle East. London, England: John Murray, 1956.

England, George, and Alfred William Pollard, eds. 1897. The Towneley Plays. New York City, NY: Charles Scribner and Company, 1952. https://archive.org/details/townleyplays00engluoft. (accessed 26 September 2015).

Hamilton, Victor P. The Book of Genesis: Chapters 1-17. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1990.

Kittel, Gerhard, and Gerhard Friedrich. Theological Dictionary of the New Testament. 10 vols. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1977.

Knowlton, Ezra Clark. 1971. The Utah Knowltons: History and genealogy of three generations of Sidney Algernon Knowlton and his descendants. In. http://michaelbro.x10host.com/utah-knowltons/#martha-jane-knowlton-and-howard-coray. (accessed August 9, 2018).

Koester, Helmut, and Thomas O. Lambdin. "The Gospel of Thomas (II, 2)." In The Nag Hammadi Library in English, edited by James M. Robinson. 3rd, Completely Revised ed, 124-38. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, 1990.

Marshall, Elaine S. "The power of God to heal: The shared gifts of Joseph and Hyrum." In Joseph and Hyrum — Leading As One, edited by Mark E. Mendenhall, Hal B. Gregersen, Jeffrey S. O’Driscoll, Heidi S. Swinton and Breck England, 165-84. Provo and Salt Lake City, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Deseret Book, 2010. https://rsc.byu.edu/joseph-hyrum-leading-one/power-god-heal. (accessed August 8, 2018).

McConkie, Bruce R. A New Witness for the Articles of Faith. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1985.

Nibley, Hugh W. "On the sacred and the symbolic." In Temples of the Ancient World, edited by Donald W. Parry, 535-621. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1994. Reprint, Nibley, Hugh W. “On the Sacred and the Symbolic.” In Eloquent Witness: Nibley on Himself, Others, and the Temple, edited by Stephen D. Ricks. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 17, 340-419. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2008.

———. 1975. The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment. 2nd ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005.

"One Seven-Dip Saint. Manuscript in the possession of Jeffrey M. Bradshaw obtained from Knowlton/Coray family member Kari Maxwell on August 8, 2018."

Quinn, D. Michael. "The practice of rebaptism at Nauvoo." BYU Studies 18 (Winter 1978): 226-32. https://byustudies.byu.edu/content/practice-rebaptism-nauvoo. (accessed August 8, 2018).

Riesenfeld, Harald. The Resurrection in Ezekiel XXXVII and in the Dura-Europos Paintings. Uppsala Universitets Arsskrift 11. Uppsala, Sweden: Almqvist and Wiksells, 1948.

Robinson, J. The First Book of Kings. The Cambridge Bible Commentary on the New English Bible, ed. P. R. Ackroyd, A. R. C. Leaney and J. W. Packer. Cambridge, England: University of Cambridge, 1972.

Seaich, John Eugene. Was Freemasonry derived from Mormonism? In Scholarly and Historical Information Exchanged for Latter-day Saints (SHIELDS). http://www.shields-research.org/General/Masonry.html. (accessed November 6, 2007).

———. Ancient Texts and Mormonism: Discovering the Roots of the Eternal Gospel in Ancient Israel and the Primitive Church. 2nd Revised and Enlarged ed. Salt Lake City, UT: n. p., 1995.

Smith, Joseph, Jr. The Words of Joseph Smith. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1980. https://rsc.byu.edu/archived/words-joseph-smith-contemporary-accounts-nauvoo-discourses-prophet-joseph/1843/21-may-1843. (accessed February 6, 2016).

Smith, Joseph, Jr., Andrew H. Hedges, Alex D. Smith, and Richard Lloyd Anderson. Journals: December 1841-April 1843. The Joseph Smith Papers, Journals 2, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin and Richard Lyman Bushman. Salt Lake City, UT: The Church Historian’s Press, 2011.

Smith, Joseph, Jr. 1902-1932. History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Documentary History). 7 vols. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1978.

———. 1938. Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1969.

Smith, Lucy Mack. 1853. Lucy’s Book: A Critical Edition of Lucy Mack Smith’s Family Memoir. Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books, 2001.

Sparks, Jack Norman, and Peter E. Gillquist, eds. The Orthodox Study Bible. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 2008.

Stapley, Jonathan A., and Kristine Wright. "’They shall be made whole’: A history of baptism for health." Journal of Mormon History 34 (Fall 2008): 69-112. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1664180. (accessed August 8, 2018).

Stapley, Jonathan A. "The forms and the power: The development of Mormon ritual healing to 1847." Journal of Mormon History 35 (Summer 2009): 44-51. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1664187. (accessed August 8, 2018).

———. "’Pouring in oil’: The development of the modern Mormon healing ritual." In By Our Rites of Worship: Latter-day Saint Views on Ritual in Scripture, History, and Practice, edited by Daniel L. Belnap, 283-316. Provo and Salt Lake City, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Deseret Book, 2013. https://rsc.byu.edu/our-rites-worship/pouring-oil-development-modern-mormon-healing-ritual. (accessed August 8, 2018).

Tate, Charles D., Jr. "Howard and Martha Jane Knowlton Coray of Nauvoo." In Regional Studies in Latter-day Saint Church History: Illinois, edited by H. Dean Garrett, 331-57. Provo, UT: Department of Church History and Doctrine, Brigham Young University, 1995.

Zinner, Samuel. The Vines of Joy: Comparative Studies in Mandaean History and Theology. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, in preparation.

Endnotes

21 And he stretched himself upon the child three times, and cried unto the Lord, and said, O Lord my God, I pray thee, let this child’s soul come into him again.

22 And the Lord heard the voice of Elijah; and the soul of the child came into him again, and he revived.

The importance of this symbol of the atonement was also emphasized in Egyptian temple rites (H. W. Nibley, Message (2005), p. 427):

The normal sequence of ordinances as depicted in temple reliefs is, according to Barguet, washing, laying on of hands, leading by the hand, entering the gate, embracing, and crowning. In Egyptian rites, gates or doorways are symbolic of passage and arrival, of the completion of one phase of the operation and the beginning of another; not only is the gate the normal place for the embrace of greeting and farewell, but, as the symbols and inscriptions engraved on the door frames of tombs and temples make clear, the portal itself typifies the performing of such an embrace. A spontaneous and natural gesture, embracing is not only a sign of affection but also one of acceptance, recognition, and reception at every level, from the formal and hypocritical embrace of the diplomat to the “mystical union” of the initiate. The ritual embrace is the “culminating rite of the initiation”; it is “an initiatory gesture weighted with meaning …, the goal of all consecration.”

What is the sign of the healing of the sick? The laying on of hands is the sign or way marked out by James [James 5:14–15] and the custom of ancient saints as ordered by the Lord [Acts 8:18; 1 Timothy 4:14; Hebrews 6:2], and we should not obtain the blessing by pursuing any other course except the way which God has marked out. What if we should attempt to get the Holy Ghost through any other means except the sign or way which God hath appointed. Should we obtain it? Certainly not. All other means would fail. The Lord says do so and so, and I will bless so and so.

There are certain key words and signs belonging to the priesthood which must be observed in order to obtain the blessings. The sign of Peter was to repent and be baptized for the remission of sins, with the promise of the gift of the Holy Ghost, and in no other way is the gift of the Holy Ghost obtained. … Had [Cornelius] not taken [these] sign[s or] ordinances upon him … and received the gift of the Holy Ghost, by the laying on of hands, according to the order of God, he could not have healed the sick or commanded an evil spirit to come out of a man, and it obey him [cf. Moses 1:21: “Moses received strength, and called upon God, saying: In the name of the Only Begotten, depart hence, Satan.”] for the spirits might say unto him, as they did to the sons of Sceva: “Paul we know and Jesus we know, but who are ye?” [see Acts 19:13–15].