Introduction

Jeremiah lived at the crossroads of troubled times and troubled places. He stood as a witness and a representative of an old covenant dying away with the promise of a new covenant emerging. His message was both timely and timeless. It was directed to the people of his day. It spoke to later generations of Israelites. And it yet speaks to us today as we open our scriptures and our hearts. In this lesson we will search the promises and covenants of the Lord, expressed through Jeremiah, which can be ours if we so desire, for the Lord has promised, “Whatsoever thing ye shall ask in faith, believing that ye shall receive in the name of Christ, ye shall receive it” (Enos 1:15).

Blessings that Aid Our Scriptural Searching

We are fortunate in many respects as we study the life, time, and writings of Jeremiah. We have over fifty chapters of material in the Bible written by or pertaining to Jeremiah. We have enormous archaeological and literary evidence and information of the history, culture, and life of Ancient Israel, Ancient Egypt and Ancient Mesopotamia (Assyria & Babylon((This word Babylon comes from the Akkadian language (a Semitic language related to Hebrew and Arabic) and is a composite of two words, “bab” (gate) and “ilu” (god). So it means “gate of god” most likely referring to the great temple complex dedicated to Marduk where priests could approach their god Marduk at his gate. The Hebrew world “el” (god) is related to the Akkadian word “ilu.” In the Old Testament the word for God is usually written in the Hebrew as “Elohim” which is the plural form of “el.” Interestingly, the Akkadian word “bab” (gate) has endured through the centuries and is still in use today in the Arabic language. A traveler to Egypt today when passing through doorways into buildings will often be greeted by a man who is called the “bowab” (the doorkeeper). The unwary traveler however, will give away all of his money in tips within the first day because each “bowab” asks for a tip as he opens the door for you! The Hebrew version of the word Babylon is “babel” and means “confusion” no doubt inspired by the confusion of tongues that occurred in primeval history and is recorded not only in Genesis but the Book of Ether as well as many other ancient texts.))) that pertains to the time period of Jeremiah’s life. Furthermore, we have the second witness of the Book of Mormon to events and teachings of Jeremiah’s milieu (Lehi and Jeremiah lived in Jerusalem at the same time). And finally, we have the words of modern scripture and modern prophets that continue to urge us, like Jeremiah of old, to trust in the Lord, to turn our lives to Him, to find peace and joy in penitent humility and security in the faith of a living God.

Living the Words of God

Let us now bring the words of Jeremiah to life. We will do so in several ways. First we will explore the historical and cultural background of Ancient Israel and surrounding nations during the lifetime of Jeremiah. Then we will look more closely at the life of Jeremiah, his call to be a prophet, the main contours of his message, and key events in his life. Finally, we will discuss four chapters of his writings, commenting on the significance of the words preserved over the centuries for our benefit. Ultimately, however, the words of Jeremiah, as is the case with any living words from the Lord, will not live unless we enact them in our lives.

History of the Ancient Near East

Quite often it is best for us to step back a century or so in time from the person or time period that is our main focus to begin our historical stroll. ((Much of this information is drawn from John Bright’s A History of Israel (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1981) and the entry on “Mesopotamia” in The Anchor Bible Dictionary, edited by David Noel Freedman (Doubleday: New York, 1992), 4.714-777.)) In that way, we can begin looking at the subject in a coherent, logical, and chronological framework, as if we were silent participants in the flow of history as it approaches the time period or individual that is our main focus. Such an approach allows us a much broader view and understanding of the life situations that gave context for the people and institutions of later days. So, let us take that approach with Jeremiah. We will leave aside for the moment questions about the life of Jeremiah, except to say that we are quite certain that he was born in the Kingdom of Judah around the year 640 BC and probably died in Egypt sometime after 587 BC. What was life like one hundred years before Jeremiah? What had happened in the ancient world during the century before Jeremiah’s birth? And what had specifically happened in the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah?

The Century before Jeremiah

One hundred years before the day of Jeremiah, Israel and Judah existed as independent kingdoms. We remember that they had been one unified kingdom under David and Solomon (ca. 1000-925 BC), but political and religious ruptures tore the kingdoms apart around the year 925 BC. ((See 1 Kings 12.)) For the course of two hundred years Israel, the Northern Kingdom, and Judah, the Southern Kingdom, existed as separate political entities, at times enemies with each other, at other times collaborators and allies in alliances against outside political powers (usually against the Egyptians or the Assyrians).

Fall of the Northern Kingdom (Israel)

Around the year 740 BC Israel, the Northern Kingdom, had fallen into political, moral and religious decay. The timing could not have been worse. Though the Lord raised up prophets such as Hosea to correct the problems, the mighty Assyrian Empire was expanding with renewed vigor under the direction of Tiglath-Pilesar III. Having no desire to pay tribute to a foreign enemy, the king of Israel joined an alliance with the king of Syria to protect themselves and their interests. Being small kingdoms they needed additional support. They hoped to find it in the unwilling Southern Kingdom of Judah. When Judah refused to join the ill-fated alliance of rebellion, the Syro-Ephraimite war began (734-732 BC), a war created to force Judah to join with Syria and Ephraim (Israel). Within a decade of the end of this conflict the pride of Israel had been leveled to the dust in literal humility. (( Our English word “humility” derives from the Latin word humilis which means “low” as in “low to the dust.”)) It was at this time that the Ten Tribes of Israel were taken into Assyrian captivity and lost to the records of history. Judah escaped the wrath of Assyria at this time and again twenty years later under the inspired and courageous leadership of righteous king Hezekiah and his loyal counselor, the prophet Isaiah. (( See Isaiah 36-39 for a historical treatment in scripture of the difficulty imposed upon Judah by the invading Assyrians and the mighty salvation wrought by the Living God on behalf of Judah.)) Penitent righteousness had brought the saving hand of the Lord to the Kingdom of Judah.

The Fate of the Southern Kingdom (Judah)

From a political standpoint, Hezekiah had refused to fully acquiesce to the Assyrians, and in essence was standing in outright rebellion against the mightiest empire of his day. Such a stance was not possible to maintain as the years wore on. After the turn of the century Hezekiah died (ca. 698 BC) and his young son, Manasseh, was installed on the throne. Assyria at this time was making plans to attack Egypt for its role in aiding resistance and rebellion against Assyrian westward expansion. The offensive was launched in the year 674 BC with the submission of Egypt complete by the year 663 BC. Assyria was now the undisputed power of the Ancient Near East, rebellion or resistance was political suicide, if not literal suicide for king and people. It is no wonder that at this time Manasseh consented to a vassalage status for Judah. As a political move it was probably the wisest for the security of his people and nation. However, we must not misunderstand why biblical writers spoke so disparagingly of Manasseh. It was not because he chose to relinquish Judah’s independence and sovereignty, but rather that he chose to Assyrianize Judah. This latter act was one of the reasons that the Lord’s prophets spoke out from time to time against making treaties with foreign nations; the prophets were worried that such treaties would lead to foreign incursions into the religious and cultural purity of the people of God. In an effort to display the effects of submission and vassalage to the Assyrians Manasseh imported many of their rituals and worship services. Soon altars to Assyrian astral deities had place next to the altar of Jehovah in the sacred temple of Jerusalem. The reform that his father, Hezekiah, had instituted to nationalize and centralize worship of Jehovah at Jerusalem was reversed by Manasseh. Indeed, Manasseh’s (ir)religious actions were very much like those of his grandfather Ahaz, idolatrous worship and religion that Hezekiah tirelessly worked to overcome with Isaiah throughout his reign. Unfortunately, Manasseh’s predilection for “foreign” forms of worship went further. He allowed local shrines to flourish throughout the land of Judah, shrines dedicated to any number of gods and goddesses or where worshippers inappropriately invoked the name of Jehovah in adulterated expressions of religious fervor. There also is evidence that the popularity of Assyrian forms of magic and divination were practiced in Judah, while quiet but abominable hints of human sacrifice surfaced. Ah, the peace and security of political stability at the expense of all that is lovely, virtuous, and praiseworthy. One scholar describes the situation in the following words:

It is, to be sure, probable that much of this represented no conscious abandonment of the national religion. The nature of [worshipping Jehovah] had been so widely forgotten, and rites incompatible with it so long practiced, that in many minds the essential distinction between [Jehovah] and the pagan gods had been obscured. It was possible for such people to practice these rites alongside the [worship of Jehovah] without awareness that they were turning from the national faith in doing so. The situation was one of immense, and in some ways novel, danger to the religious integrity of Israel. [The worship of Jehovah] was in danger of slipping unawares into outright polytheism. Since [Jehovah] had always been thought of as surrounded by his heavenly host, and since the heavenly bodies had been popularly regarded as members of that host, the introduction of the cults of astral deities encouraged the people both to think of these pagan gods as members of [Jehovah’s] court and to accord them worship as such. Had this not been checked, [Jehovah] might soon have become the head of a pantheon, and Israel’s faith might have been prostituted altogether. In addition to this, the decay of the national religion brought with it contempt of [Jehovah’s] law and new incidents of violence and injustice (Zeph. 1:9; 3:1-7), together with a skepticism regarding [Jehovah’s] ability to act in events (ch.1:12). Hezekiah’s reform was canceled completely and the voice of prophecy silenced; those who protested—and apparently there were those who did—were dealt with severely (II Kings 21:16). The author of Kings can say no good word of Manasseh, but instead brands him as the worst king ever to sit on David’s throne, whose sin was such that it could never be forgiven (chs.21:9-15; 24:3f.; cf. Jer. 15:1-4). ((John Bright, A History of Israel, (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1981), pp. 312-313.))

The Fall of the Assyrian Empire

The awful situation in Judah of religious and moral decay in the context of political submission would not last forever. The Assyrian empire had stretched itself beyond its capacity to administer, gathering many external and internal enemies along the way. The end was imminent. From within, the Babylonians, a distinct ethnic and political (though subjected) entity to the southeast of the main Assyrian enclaves, threatened to rebel and topple the Assyrian hegemony. From without, the Egyptians on the southwest, the Indo-Aryans from the north and the Medes from the east all pressed against the tenuous Assyrian borders. Trusting in the security of their borders and their military might, the Assyrians felt quite at ease in their prosperous cities such as Nineveh and Ashur. ((The Book of Jonah that describes one prophetic attempt to call the Assyrians to repent, with apparent success for the hand of the Lord is stayed for perhaps another generation before Assyria’s eventual collapse.)) Babylon struck the first blow against Assyria (ca. 652 BC), but in many regards it was an unexpected foe for at the time Babylon was ruled by an Assyrian governor and the brother of the Assyrian emperor. This internecine conflict played out in the theater of a civil war of sorts. In the end, Ashurbanipal ((Ashurbanipal is an Assyrian word that means “the god Ashur is the creator of an heir.” Unfortunately, this name-prophecy was short-lived for Ashurbanipal’s dynasty and empire soon came crashing to the earth within two decades of his death.)) gained the upper hand and his treasonous brother committed suicide. However, the damage was already done. Peoples within the empire and neighbors without saw the Assyrian weaknesses and sallied forth in continuous attempts to gain their independence or take the empire for themselves.

After forty years (ca. 616 BC) the situation had become desperate for the Assyrians. They no longer held tyrannical and fearsome power over the hordes of Near Eastern populations. However, not all groups desired their ultimate demise. Ironically, it was the Egyptians, erstwhile enemies of the Assyrians just fifty years before, who came to the aid of the Assyrians in order to maintain a weak, but viable government on the northern frontiers of the Fertile Crescent. This was done, in effect, to keep the advancing Babylonians and Medes at bay. The Egyptians had no desire to have a repeat of new and emerging empires follow the Assyrian example of invading Egyptian soil. However, the coalition failed and Assyria as an empire was effectively erased from the history books by 610 BC.

Before we move on, let us briefly put this into context. The year that the Assyrian Empire fell (ca. 610 BC) Jeremiah was probably thirty years old. Lehi, a contemporary of Jeremiah, may have been about the same age or perhaps a little bit older. No doubt that Nephi, Sam, Lemuel, and Laman were already alive, the older brothers approaching perhaps their teenage years. Thus we begin to have a better sense for the international political turmoil of the time, turmoil from which Judah was certainly not entirely shielded, being on the great geographical axis between Mesopotamia and Egypt and turmoil which undoubtedly informed the life experience of Lehi and his family.

A New King for Judah

We will momentarily move the clock back once again to the year 640 BC. However, we are not yet ready to shine our full focus on Jeremiah (this being the likely year of his birth). Let us first discuss the political and religious scene within Judah now that we have a clearer backdrop of the international problems that framed life in Judah. Previously we considered the wicked ways of Judean king Manasseh son of Hezekiah. To the relief of not a few religious purists he passed away around 641 BC only to be succeeded by his like-minded son Amon. ((These patterns of kingly (father-to-son) wickedness bear striking resemblance to episodes in the Book of Ether.)) That his ways of religious adultery would not be tolerated by all is born out in the fact that after but two years on the throne of David an assassination plot ended his life. Amon’s young son, Josiah was then heralded as the new king of Judah at the tender age of eight. No doubt that the first many years of his reign were orchestrated by powerful court officials who had their own agendas, many of which were supported by religious reformers. What many of the people most desired was political independence. Among the religious reformers this independence would be displayed by expanding Judean borders to encompass what was once the entire geographical domain of David. Judah had been reduced to but a small petty state at that point encompassing only 25% of what had been the former glory of Israel’s golden age. Josiah also reinstalled national and centralized worship of Jehovah at the national shrine known as the Jerusalem Temple. As long as foreign powers held political dominance over Judah, the religious reformers and religious purists believed (and with some justification) that commingled religion, worship, and rites would forever profane the sacred places of Judah.

Independence for Judah

As Assyrian hegemony waned and Josiah grew bolder the propitious moment for action arrived. In 628 BC, king Ashurbanipal died and his ineffectual son took the throne. Josiah, then a courageous young man of twenty years, seized the opportunity to work independent of any Assyrian lordship. He brought about political independence and religious reformation, following in the steps of his grandfather Hezekiah. He began by expanding the Judean borders, first to reclaim the area of Samaria (what had previously been the domain of the Ten Northern Tribes of Israel until they had been conquered and deported a century before by the Assyrians). Later military attempts were made to regain the Galilee region. ((This brought about his unfortunate and premature death in a battle at Megiddo ca. 609 BC.)) His religious reforms included cleansing the Jerusalem temple of religious and political symbols and rites associated with the Assyrian empire and Assyrian pagan religions. He also enacted a return to the purity of Israelite worship of Jehovah, advocating one national, centralized location where such legitimate worship could take place. The local family, community and village shrines throughout the countryside were summarily closed and any priests of Jehovah were required to incorporate themselves with the authorized priesthood at Jerusalem. We cannot delve into all of the social upheaval that such reforms would cause but it is clear that not all people were happy with or socially and economically benefited from such reforms.

Book of the Law Discovered

One of the greatest aspects of the religious reform was the unanticipated discovery of the book of the law (most likely our present day Book of Deuteronomy or some version of it) in the year 622 BC. As the priests were obeying orders to cleanse the temple of disrepair Hilkiah, the high priest, discovered the sacred book, which was soon delivered to the king. Josiah read it with much sorrow, for the people had so fully forgotten the Lord that even their most revered scripture had been forgotten and lost somewhere in the sacred temple precincts. Such a discovery only fueled Josiah’s enthusiasm and desire for religious reform. In an awesome display of covenantal ritual he read the book of the law to his people and committed them to obey the voice of the Lord. In covenantal unity and affirmation the people took upon themselves the name of Jehovah, to serve him, and to keep his commandments according to the words written in the book of the law (see 2 Kings 23). ((This powerful display of covenantal worship and commitment is paralleled in striking similarity in the Book of Mormon in what we know as King Benjamin’s speech. See Mosiah 2-6.))

A New Golden Age?

A renewed Golden Age appeared to be dawning over Israel once again. A legitimate and righteous heir of David sat upon the throne. But the religious awakening of returning to the true worship of Jehovah would not last. And interestingly, the national independence disappeared soon thereafter (ca. 608 BC). What was the cause of such rapid reversals of fortune in the course of some forty years (subjection to the Assyrians until 628 BC, independence after 628 BC and subjection to a foreign power once again beginning about 608 BC)?

Misfortune for Judah

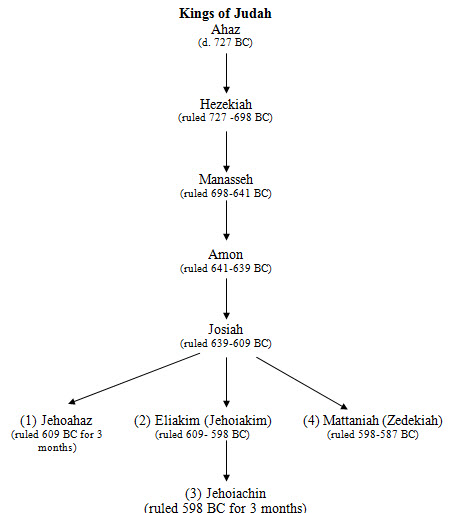

After the Assyrian empire fell into demise, emergent kingdoms warred over the loot (land and property) of such a vast empire. Egypt was one in particular who wanted to reassert power in the region. With that intent the Egyptian army took the 800 mile march from Egyptian lands to the city of Carchemish (a strategic Mesopotamian city on the Euphrates river about 450 miles northwest of Jerusalem) to take a stand against the rising Babylonian empire. For reasons that we do not entirely understand, Josiah sought to thwart the Egyptian march through his country side, which had to pass by the strategic fortress city of Megiddo which lay in the fertile Jezreel valley (about 50 miles north of Jerusalem). On the ill-fated day of battle Josiah lost his life and thus passed with him the promise of national independence and religious reform. Summarily Josiah’s son Jehoahaz became king of Judah at the age of twenty-three, this being the year 609 BC. ((For more scriptural details of the Egyptian military campaign, Josiah’s failed attempt to stop the march and Jehoahaz’s rise to the throne see 2 Kings 23:29ff and 2 Chronicles 35:20-24.))

Loss of Independence for Judah

When the Egyptians returned from the failed military expedition against the Babylonians (609 BC), they removed Jehoahaz from power and in his place installed his brother Eliakim on the throne (he assumed the throne name of Jehoiakim), ((In Ancient Near Eastern Tradition a king had two names: his birth name and his throne name. In essence, when the new king took the throne he received a new name to mark that he had received royal power from God to serve as the king.)) perhaps because he would be more loyal to Egyptian interests. Judah’s independence disappeared at this point for Egypt had also put Judah under tribute. Jehoiakim did not walk after the ways of his father Josiah to do righteousness. Instead, the religious awakening that had begun with Hezekiah and that was vigorously renewed with Josiah once again was reversed, much like Manasseh had done. Those who understood the ways of the Lord condemned such wickedness, though often it put their very lives in jeopardy. In this regard, Jeremiah the prophet was particularly vulnerable as was Lehi who eventually had to flee Jerusalem with his family.

The Wickedness of Jehoiakim

Under heavy tribute the economic and temporal conditions of the kingdom of Judah foundered. Unfortunately, the moral backbone that may have kingdom survive such trials and tribulations was seriously lacking. Why? Jehoiakim allowed for popular forms of pagan worship and ritual to reenter public and private life instead of turning to the Lord God. In such destitute circumstances, Jehoiakim displayed his total disregard for the well-being of his people. He moved forward with great arrogance to build himself a beautiful and spacious palace by means of forced labor. This wickedness Jeremiah vigorously denounced (see Jeremiah 22:13-19).

Changing Vassalage

Some six years (603 BC) after the Egyptians put the Judean kingdom into vassalage status, the Babylonian empire was sufficiently strong enough to contend with the Egyptians. Into the lands of Palestine the Babylonians poured on their way to conquer Egypt. Though wicked, yet having enough political wisdom to see the turn of events, Jehoiakim astutely threw in his allegiance with the Babylonian overlords, submitting to be their vassal and to pay the annual tribute.

Jerusalem under Siege

Jehoiakim had no desire for such vassalage status so when the opportunity arose, he rebelled. This rebellion lasted for about 3 years (601-598 BC) before the Babylonians could return to Palestine and put down the insurrection. But Jehoiakim died just before the Babylonian war machine arrived to Jerusalem (597 BC). For a brief three months his young eighteen year-old son Jehoiachin held the Judean throne. When the Babylonian army arrived, they put down the Judean king and deported a large portion of the most important people of the city back to Babylon. In essence, the fall of Jerusalem took place in stages, the earliest stage occurring in 597 BC while the majority of the destruction and deportation was not complete until 587 BC, the traditional date of the “Fall of Jerusalem.”

Zedekiah Becomes King of Judah

The Babylonians installed a new king on the Judean throne in 597 BC, one that they believed would be loyal to them and faithfully pay the tributary taxes on a regular basis. This king was named Mattaniah and he assumed the throne name of Zedekiah, the same Zedekiah mentioned by Nephi in 1 Nephi 1. Unfortunately for Zedekiah and his people, Zedekiah followed in the footsteps of his seditious brother Jehoiakim. So, after ten years of such behavior the Babylonian desired no more. They marched upon Jerusalem, put the people to the sword, burnt the temple to the ground, and removed anyone of consequence to Babylon. Thus passed away the era of the 1st Solomonic temple. ((A second temple was begun about seventy years later after some Jews returned from exile under the direction of Zerubbabel (this names means “born in Babylon”). It was this second temple which King Herod (37 – 4 BC) later enlarged and refurbished, which was known to Jesus and the people of his day.)) And thus came an end to the rule of kings over Israel and Judah.

The Prophet Jeremiah

Jeremiah lived through all of the events that we have recently witnessed in this narrative. ((Much of the information concerning Jeremiah is drawn from John Bright’s A History of Israel and from the entry on “Jeremiah” in The Anchor Bible Dictionary, 3.684-698.)) Indeed, he played a role in some of these great events, crying out to the people to be submissive to God, penitent in their hearts, and to cease sedition against an enemy that was willing to destroy all hopes of peace. But he was not alone in his prophetic work. God called other prophets at this time to preach penitent fidelity to his love and covenants. Among the prophets contemporary with Jeremiah we find the names of Zephaniah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Lehi, Ezekiel, and others.

With this historical framework in place, let us explore more fully the life of Jeremiah, the times in which he lived, and the timely and timeless message he has left for the ages. A summary of Jeremiah’s life in the context of national and international problems raging during his life time is best expressed in the words of John Bright:

No braver or more tragic figure ever trod the stage of Israel’s history than the prophet Jeremiah. His was the authentic voice of [the] Mosaic [covenant] speaking, as it were, out of season to the dying nation. It was his lot throughout a long lifetime to say, and say again, that Judah was doomed and that that doom was [Jehovah’s] righteous judgment upon her for her breach of covenant.

Thanks to a wealth of biographical material in his book, the story of Jeremiah’s life is better known than that of any other prophet. Born toward the end of Manasseh’s reign in the village of Anathoth, just north of Jerusalem, he was still a lad ((Jeremiah received his call as a prophet from the Lord while still a very young man. He was probably about the age of Joseph Smith at the time of the first vision, making him about 14 years old. This was the year 627 BC. We learn in Jeremiah 1:5 that the Lord had foreordained Jeremiah to be a prophet unto the nations. The Lord knows who he calls and he will magnify those that he calls. Elder Eyring spoke of these truths at the October 2002 General Conference when he offered the following counsel about receiving callings from the Lord: “First, you are called of God. The Lord knows you. He knows whom He would have serve in every position in His Church. He chose you. He has prepared a way so that He could issue your call…You are called to represent the Savior. Your voice to testify becomes the same as His voice, your hands to lift the same as His hands. His work is to bless His Father’s spirit children with the opportunity to choose eternal life. So, your calling is to bless lives…Your call has eternal consequences for others and for you. In the world to come, thousands may call your name blessed, even more than the people you serve here…Just as God called you and will guide you, He will magnify you. You will need that magnification. Your calling will surely bring opposition. You are in the Master’s service. You are His representative. Eternal lives depend on you. He faced opposition, and He said that facing opposition would be the lot of those He called.”)) when he began his career five years before the lawbook was found in the Temple (ch.1:1f., 6). He was of priestly stock, his family possibly tracing its descent from the priesthood of the ancient Ark shrine at Shiloh—which might help to explain Jeremiah’s profound feeling for Israel’s past, and for the nature of the [Mosaic] covenant…Both Jeremiah and Zephaniah…[assailed] the paganism that Manasseh had fostered, [which] helped to prepare the climate for more thoroughgoing reform. Though it is unlikely that Jeremiah participated actively in the reform itself, he certainly must have approved of its eradication of pagan practices and its attempt to revive the theology of the Mosaic covenant. He both admired Josiah greatly (ch.22:15f.) and, as that king pushed his program of reunification, hoped for the day when a restored Israel would join Judah in the worship of [Jehovah] in Zion (ch.3:12-14; 31:2-6, 15-22). But, as we have also seen, he soon had misgiving. He saw a busy cult, but no return to the ancient paths (ch.6:16-21); a knowledge of [Jehovah’s] law, but an unwillingness to hear [Jehovah’s] word (ch.8:8f.); and a clergy that offered the divine peace to a people whose crimes against the covenant stipulation were notorious (chs.6:13-15; 8:10-12; 7:5-11). He realized that the demands of covenant had been lost behind cultic externals (ch.7:21-23), and that the reform had been a superficial thing that had effected no repentance (chs.4:3f.; 8:4-7).

Jeremiah, who was early haunted by that premonition of doom which ultimately became well-nigh his entire burden, found his disillusionment complete under Jehoiakim. As that king allowed the reform to lapse, Jeremiah began to preach the nation’s funeral oration, declaring that, having revolted against its divine King (ch.11:9-17), it would know the penalties that [Jehovah’s] covenant holds for those who breach its stipulations. The humiliation of 609…[was] something the nation brought on itself by forsaking [Jehovah] (ch.2:16). But that punishment, he warned, was only provisionary, for [Jehovah] was sending “from the north” the agent of his judgment, now seen as the Babylonians (e.g., chs.4:5-8, 11-17; 5:15-17; 6:22-26), who would fall upon the unrepentant nation and destroy it without remnant (e.g., chs.4:23-26; 8:13-17).

Standing thus in the theology of the Mosaic covenant, Jeremiah rejected the national confidence in the Davidic promises utterly. ((The Davidic promises, given unto King David by the Lord, promised David a dynasty and property (see The Anchor Bible Dictionary “Davidic Covenant” 2.69-72). Apparently David felt that it was an eternal covenant that could never be broken (see Psalm 89:4-5). The people of Israel (this before the two kingdoms split) apparently were partakers of the blessings and benefits of this covenant. Thus, during the time of Jeremiah many people took security in a nearly 400 year old covenant, believing that they could do anything that they wanted without consequence and that God would maintain his covenant. Jeremiah knew better. Jeremiah recognized that any covenant is null and void, even if one of the subscribing parties is God Himself, if any party is not true and faithful, (i.e. if God’s children fail to be obedient to his laws).)) He did not, to be sure, deny that those promises had theoretical validity (cf. ch.23:5f.), nor did he reject the institution of the monarchy as such. But he was convinced that, since the existing state had failed of its obligation, neither it nor its kings would know anything of promises (chs.21:12 to 22:30): [Jehovah’s] promise to it was total ruin! The popular trust in [Jehovah’s] eternal choice of Zion he branded a fraud and a lie, declaring that [Jehovah] would abandon his house and give it over to destruction, as he had the Ark shrine of Shiloh (chs.7:1-15; 26:1-6).

The persecution that such words earned Jeremiah, and the agony it cost him to utter them form one of the most moving chapters in the history of religion. Jeremiah was hated, jeered at, ostracized (e.g., chs.15:10f., 17; 18:18; 20:10), continually harassed, and more than once almost killed (e.g., chs.11:18 to 12:6; 26; 36). In thus dooming state and Temple, he had, as the official theology saw it, committed both treason and blasphemy; he had accused [Jehovah] of faithlessness to his covenant with David (cf. ch.26:7-11)! Jeremiah’s spirit almost broke under it. He gave way to fits of angry recrimination, depression, and even suicidal despair (e.g., chs.15:15-18; 18:19-23; 20:7-12, 14-18). He hated his office and longed to quit it (e.g., chs.9:2-6; 17:14-18), but the compulsion of [Jehovah’s] word forbade him to be silent (ch.20:9); always he found strength to go on (ch.15:19-21)—pronouncing [Jehovah’s] judgment. Yet when that judgment came, it brought him the deepest agony (e.g., chs.4:19-21; 8:18 to 9:1; 10:19f).

After 597, when it seemed that judgment had been accomplished and wild hopes of speedy restoration were abroad, Jeremiah continued his monotone of doom. Seeing no sign that any lesson had been learned, or any repentance effected by the tragedy, he declared that the people—what a twist on Isaiah’s theme (Isa. 1:24-26)!—were refuse metal which could not be refined (Jer. 6:27-30). Indeed, it seemed to him (ch.24) that the best fruit of the nation, and its hope, had been plucked away, leaving only worthless culls. Yet, when (594) hope flared that Jehoiachin would soon return, Jeremiah denounced it and, wearing an ox yoke on his neck (ch.27f.), declared that God himself had placed Babylon’s yoke on the neck of the nations, and that they must submit to it or perish.

When final rebellion came [c.587 BC], Jeremiah unwaveringly predicted the worst, announcing that there would be no intervening miracles, but that [Jehovah] himself was fighting against his people (ch.21:1-7). When hopes soared as the Egyptians advanced [against Judah’s overlord Babylon] (ch.37:3-10), he dashed them without pity. He even went so far as to advise people to desert (ch.21:8-10)—which many did (chs.38:19; 39:9). For this, he was put in a dungeon where we very nearly died (ch.38). The Babylonians finally released him and, thinking that he had been on their side (ch.39:11-14), allowed him to choose between going to Babylon and remaining behind. He elected to stay (ch.40:1-6). But after Gedaliah’s assassination, the Jews who fled to Egypt took [Jeremiah] with them against his will; and there he died. The last words reported from his lips (ch.44) were still of judgment on his people’s sin. ((Bright, A History of Israel, pp. 333-336.))

I realize that this is a hefty amount of historical material that does not initially seem to be of the greatest spiritual worth. However, when we have a clearer understanding of the history of God’s people and the choices of righteousness or wickedness that they made and the consequences for such choices, we can look at our own lives and find relevant application and hopefully, as in the words of Moroni, be wiser than they were. ((“Condemn me not because of mine imperfection, neither my father, because of his imperfection, neither them who have written before him; but rather give thanks unto God that he hath manifest unto you our imperfections, that ye may learn to be more wise than we have been” (Mormon 9:31).)) An additional benefit to all of this historical background is quite important to our understanding of the Book of Mormon. When we remember that Lehi and his family were contemporaries of Jeremiah and lived in Jerusalem at the same time, we recognize that all of this history is a backdrop for the Book of Mormon. We now begin to have a very clear picture of the world in which Lehi, Sariah, Nephi, Sam, Laman, and Lemuel lived. We also have a better understanding of what they thought, knew and experienced and thus what they brought with them over to the New Promised Land.

Jeremiah and His Message

This particular article is only specifically focused on elucidating four of the more than fifty chapters in the Book of Jeremiah (16; 23; 29; 31). Even though we will not be able to completely treat the power and fullness of Jeremiah’s message we have sufficient historical backdrop to deeply explore any of the chapters and those chapters that we will discuss will give us sufficient taste of his message and words. My approach will be something akin to a commentary, which by its nature hopes to explicate specific passages, and with a little creativity can highlight common themes across several passages. Before looking at the specific passages we should mention a few themes that cut across the pages of Jeremiah: Israel is a covenant people; God will gather his covenant people both as individuals and as a group; covenant relationships are sacred and binding.

Jeremiah 16

Jeremiah 16:1-9

In these verses the Lord commands Jeremiah to speak out against getting married, mourning for the dead, or participating in celebrations and feasts. At first glance we might be somewhat confused why the Lord would speak against those things that deal with the bonds of loving family relationships. It is not that God despises marriage or that participating in the acts of remembering dead ancestors are worthless, ((In the Ancient Near Eastern culture many societies had cults of the dead. In other words, these were rituals and activities for families to remember their deceased ancestors. It was a way of gathering the family together to show respect to those who had passed on to the next life. Among the activities that would take place, the father officiating as priest at the family shrine located in the home, was a meal and drinking of wine. It was believed that the deceased ancestors needed to receive food and drink. So for the food and drink offered to the deceased the individuals in the family did eat and drink in kind. This could lead to much merriment and in some cases insobriety if too many wine libations were poured in behalf of the deceased. Thus Jeremiah spoke out against these things. How could the people be merry at a time when they should be in sackcloth and ashes as they repented of their many sins? See The Anchor Bible Dictionary “Dead, Cult of The” 2.105-108.)) but God wanted his people of Judah to understand how serious and imminent the threat of destruction was. His people had every need to repent; the day of repentance is not a day of festivals, celebration, and mirth. Additionally, by telling the people not to contract marriage covenants the Lord was warning that destruction would come swiftly and soon by the hand of the Babylonians.

Jeremiah 16:10-13

How unfortunate it was that when Jeremiah preached the message of repentance to the people of Judah they responded,

[Why] hath the Lord pronounced all this great evil against us? or what is our iniquity? or what is our sin that we have committed against the Lord our God? (v.10)

This is akin to the insolent response of a certain group of Nephites in the Book of Mormon during the reign of wicked king Noah. When Abinadi was sent among that people to call them to repentance they bound him in anger and brought him before king Noah with accusation and feigned innocence saying,

O king, what great evil hast thou done, or what great sins have thy people committed, that we should be condemned of God or judged of this man? And now, O king, behold, we are guiltless, and thou, O king, hast not sinned; therefore, this man has lied concerning you, and he has prophesied in vain. And behold, we are strong, we shall not come into bondage, or be taken captive by our enemies; yea, and thou hast prospered in the land, and thou shalt also prosper. Mosiah 12:13-15

Perhaps we should not be entirely surprised at such gross wickedness born of ignorance among these Nephites for we read in the following passage that such sinful audacity was modeled by king Noah himself:

Now when king Noah had heard of the words which Abinadi had spoken unto the people, he was also wroth; and he said: Who is Abinadi, that I and my people should be judged of him, or who is the Lord, that shall bring upon my people such great affliction? Mosiah 11:27

We should pause for a moment to consider if we are like these Nephites in any way. Do we believe that we are safe and secure from bondage because we are strong or because we have mighty cities and armies? There is only one sure path to safety and security: “Our safety lies in repentance. Our strength comes of obedience to the commandments of God.” ((Gordon B. Hinckley, “The Times in Which We Live” Ensign (November, 2001), p. 74.))

Like the Nephites of old we also see in verses 10-13 of chapter 16 that Jeremiah’s generation of Israelites had done worse than their fathers. Instead of worshipping dumb idols they had turned to worshipping the vain imaginations of their own hearts! They trusted in themselves and not in the almighty power of God. Do we do this today?

Jeremiah 16:14-21

Though harsh the condemnation of the prior verses, the everlasting kindness and mercy of our God shines through as He promises to gather in his people in love, offering them the terms of temporal and spiritual salvation. These verses describe some of the ways in which God will seek out his people. The Lord knows his people, he knows where and how to find them, and they will ultimately know that the Lord is God.

Jeremiah 23

Jeremiah 23:1-8

When righteous king Josiah was killed in battle against the Egyptians at Megiddo (609 BC), his son Jehoiakim (also known as Eliakim) came to throne after his older brother Jehoahaz ruled for a short three month period. Jehoiakim, as we learned earlier, stopped the religious reformation which his father had instituted and instead returned to the old ways of paganism while wickedly practicing social injustice against his own people. Jeremiah spoke out in righteous anger against this wickedness declaring that such iniquity would not go unpunished. Following these condemnations Jeremiah spoke words of redemption and promise, saying that eventually a righteous heir to the throne of David would rule over Israel. Jesus Christ is that heir and we are His people who have Him as our King.

Jeremiah 23:9-40

Not only did Jeremiah have to deal with the iniquity of state sponsored wickedness during the eleven year reign of king Jehoiakim, Jeremiah had to constantly battle against false prophets and against the charges that he was a false prophet. Apparently during Jeremiah’s time, there were those who believed that they could simply say, “thus saith the Lord” and that the message they had to deliver would then be automatically authenticated by God himself. Many arose in the days of Jeremiah as self-proclaimed prophets, leading the people astray with flatteries and lies, claiming that they spoke for God. These false prophets were in reality servants of the father of all lies who was the one they had chosen to follow. The mighty prophet Nephi once spoke about such false messages, false prophets and the people who gave heed to such deceit:

For behold, at that day shall he rage in the hearts of the children of men, and stir them up to anger against that which is good. And others will he pacify, and lull them away into carnal security, that they will say: All is well in Zion; yea, Zion prospereth, all is well—and thus the devil cheateth their souls, and leadeth them away carefully down to hell. And behold, others he flattereth away, and telleth them there is no hell; and he saith unto them: I am no devil, for there is none—and thus he whispereth in their ears, until he grasps them with his awful chains, from whence there is no deliverance. Yea, they are grasped with death, and hell; and death, and hell, and the devil, and all that have been seized therewith must stand before the throne of God, and be judged according to their works, from whence they must go into the place prepared for them, even a lake of fire and brimstone, which is endless torment. Therefore, wo be unto him that is at ease in Zion! Wo be unto him that crieth: All is well! Yea, wo be unto him that hearkeneth unto the precepts of men, and denieth the power of God, and the gift of the Holy Ghost! Yea, wo be unto him that saith: We have received, and we need no more! And in fine, wo unto all those who tremble, and are angry because of the truth of God! For behold, he that is built upon the rock receiveth it with gladness; and he that is built upon a sandy foundation trembleth lest he shall fall. Wo be unto him that shall say: We have received the word of God, and we need no more of the word of God, for we have enough! 2 Nephi 28:20-29

We learn from the words of Jeremiah that God promises to destroy such false prophets. ((As a sign that he fulfills such promises read the story of Jeremiah’s contest with the false prophet Hananiah in Jeremiah 28.)) What is interesting about God’s promise to destroy false prophets is that the Lord had told his people that they can detect false prophets in the following way: if a prophet prophesies falsely he will die. The people of Israel understood this and often endeavored to bring this to pass of their own doing. In other words, if a prophet came to them with a message that they did not want to obey they believed that they simply needed to kill the prophet to “fulfill” the words of God that a false prophet will die. Thus they could deceive themselves, through their own murderous act, that the prophet who had called them to repentance was simply a false prophet. This did indeed happen in the days of Jeremiah and so he had every reason to fear for his life:

And there was also a man that prophesied in the name of the LORD, Urijah the son of Shemaiah of Kirjath-jearim, who prophesied against [Jerusalem] and against this land according to all the words of Jeremiah: And when Jehoiakim the king, with all his mighty men, and all the princes, heard his words, the king sought to put him to death: but when Urijah heard it, he was afraid, and fled, and went into Egypt; And Jehoiakim the king sent men into Egypt…And they fetched forth Urijah out of Egypt, and brought him unto Jehoiakim the king; who slew him with the sword, and cast his dead body into the graves of the common people. ((The name Urijah means “Light of Jehovah.” In symbolic and analogous terms wicked king Jehoiakim murdered the light of Jehovah.)) Jeremiah 26:20-23

On several occasion the people also sought the life of Jeremiah (see Jeremiah 26) and this is akin to what happened to the righteous Abinadi in Book of Mormon. Both came to the people of God calling them to repentance. In both instances the people were angry and brought railing accusations against the prophet while clamoring for the king to put the prophet to death.

| Jeremiah 26:8, 21 | Mosiah 11:26-28 |

| 8 Now it came to pass, when Jeremiah had made an end of speaking all that the LORD had commanded him to speak unto all the people, that the priests and the prophets and all the people took him, saying, Thou shalt surely die…21 And when Jehoiakim the king, with all his mighty men, and all the princes, heard his words, the king sought to put him to death | 26 Now it came to pass that when Abinadi had spoken these words unto [the people] they were wroth with him, and sought to take away his life; but the Lord delivered him out of their hands.27 Now when king Noah had heard of the words which Abinadi had spoken unto the people, he was also wroth; and he said…28 I command you to bring Abinadi hither, that I may slay him, for he has said these things that he might stir up my people to anger one with another, and to raise contentions among my people; therefore I will slay him. |

Jeremiah was spared, but Abinadi was not. His fate was similar to the prophet Urijah who died at the hands of a wicked king and wicked people to seal the witness of his testimony (Jeremiah 26:20-23).

Jeremiah 29

Jeremiah 29:1-9

Jeremiah directs this message to the Jews already in Babylon. We remember that an initial deportation of Jews occurred in 597 BC (the full destruction of Jerusalem took place ten years later). He tells the Jews in Babylon to build houses, plant gardens and move forward with life. Why? In essence, his message indicates to them that they will be in bondage for a long time. Jeremiah again admonishes the people to turn away from false prophets.

Jeremiah 29:10:19

In these verses Jeremiah speaks forth the words of comfort and promise that one day the people of God will be returned and restored into their lands of inheritance. Jeremiah reminds the people of the loving mercy of God who sends true prophets unto them to teach them the things of truth.

Jeremiah 29:20-32

Unfortunately, however, Jeremiah had to once again contest against false prophets who had appointed themselves as spokesman for God, leading the people away with vain and flattering lies.

Jeremiah 31

This is a chapter of restoration and thus it speaks of how all of the mighty promises from the ancient days will be fulfilled in the Lord’s due time. All of the beautiful symbols of life, prosperity, peace, joy, and happiness are employed throughout this chapter. God’s everlasting mercy and kindness ((The English word “loving-kindness” is translated from the Hebrew word hesed. This unique and special Hebrew word carries powerful significance. One scholar has said the following things about the Biblical word hesed: “In general one may identify three basic meanings of the word, which always interact: ‘strength,’ ‘steadfastness,’ and ‘love.’ Any understanding of the word that fails to suggest all three inevitably loses some of its richness. ‘Love’ by itself easily becomes sentimentalized or universalized apart from the covenant. Yet ‘strength’ or ‘steadfastness’ suggest only the fulfillment of a legal or other obligation…Marital love is often related to hesed. Marriage certainly is a legal matter, and there are legal sanctions for infractions. Yet the relationship, if sound, far transcends mere legalities. The prophet Hosea applies the analogy to Yahweh’s [Jehovah’s] hesed to Israel within the covenant (e.g., 2:21). Hence, ‘devotion’ is sometimes the single English word best capable of capturing the nuance of the original. The [Revised Standard Version Translation] attempts to bring this out by its translation, ‘steadfast love.’ Hebrew writers often underscored the element of steadfastness (or strength) by paring hesed with `emet (‘truth, reliability’) and `emunah (‘faithfulness’).” Vine, Vine’s Complete Expository Dictionary of Old and New Testament Words, p. 142.)) is redolent throughout. The Lord promises to establish a new, solemn, and binding covenant with his people Israel. Just as he had delivered Israel from Egyptian bondage with a covenant, so too would God deliver his people from Babylonian bondage with a new covenant. And we are children of the covenant. God will deliver us still with a covenant and a promise which cannot be broken except through faithlessness and disobedience.

In these troubled times may we see the relevance of Jeremiah’s timely and timeless message today for our lives and by so doing reap the ripe fruit of this life’s purpose that “men are, that they might have joy.” 2 Nephi 2:25

praise the Lord For the prophet Jeremiah i have always felt for him and the time he lived in trying so hard to get the people to turn there hearts back to the living breathing ever present one and only God . Much like today there are words of God in the world telling people his people the signs of the time and the never ending Love That God has for his people Now here we are in 2022 with the world plagued by three pandemics and the only person we can turn to is The Lord God himself for eternal safety . I am certainly no prophet But i do love and believe that He is here in the hearts of every living individual worldwide and thus he is the living breathing one and only Living God who lives and breaths in the hearts of every single one of us. Glory To God thank You Jesus for your sacrifice and resurrection . Revelation 19.

When did the lds start to interpret vs 16 as missionary work?

Thank you, Taylor. The background you provide is most helpful in understanding the writings of Jeremiah, Nephi and other Book of Mormon authors.