An Old Testament KnoWhy[1]

relating to the reading assignment for

Gospel Doctrine Lesson 26:

King Solomon: Man of Wisdom, Man of Foolishness

(1 Kings 3; 5-11) (JBOTL26A)

A video version of this article is available on the Interpreter Foundation and FairMormon YouTube channels.

Note: Jeff and his wife, Kathleen, have just returned from their mission. This series of Old Testament KnoWhy articles will resume sometime in the first half of August.

Figure 1. Stephen T. Whitlock: View of the Jerusalem Archaeological Park (Ophel Walls site) from the southwest corner, 2017. The park was opened in 2011, following excavations by Eilat Mazar. Some think the ruins were part of a “complex of fortifications that King Solomon constructed in Jerusalem: ‘…until he had made an end of building his own house, and the house of the Lord, and the wall of Jerusalem round about.'”[2]

Question: Why does “Holiness to the Lord” appear on LDS temples? Was the phrase used on buildings anciently?

Summary: The Wikipedia article on LDS temples asserts that the phrase “Holiness to the Lord” was inscribed “on the Old Testament Temple of Solomon.”[3] However, so far as we know, the phrase was never used as part of any ancient building. It is unique to modern temples. In this article we will address three questions:

- How did the practice of inscribing LDS temples with the words “Holiness to the Lord” begin?

- What was the meaning of the phrase in the Old Testament?

- What is the purpose of modern temples?

The Know

How did the practice of inscribing LDS temples with the words “Holiness to the Lord” begin?

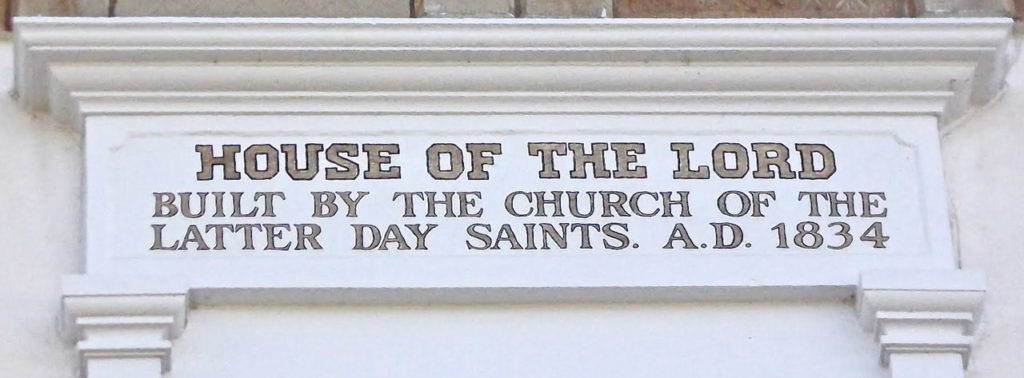

Figure 2. Inscription over the entrance to the Kirtland House of the Lord[4]

Kirtland. The Kirtland “House of the Lord”[5] prominently displays this inscription tablet over the entrance. However, the words “Holiness to the Lord” — included on every other LDS temple — are missing. That said, there is no question but that Joseph Smith considered the temple a place of holiness. His dedicatory prayer included an entreaty “that all people who shall enter upon the threshold of the Lord’s house may feel thy power, and feel constrained to acknowledge that … it is thy house, a place of thy holiness.”[6]

Figure 3. Drawing by William Murphy, a former resident of Nauvoo, in 1868[7]

Nauvoo. The original drawings of the Nauvoo temple do not show an inscription plaque on the façade. However, in 1845 Brigham Young directed the temple architect “to place a stone in the west end of the Temple with the inscription ‘Holiness to the Lord’ thereon.”[8]

The application of the phrase to the temple reflected the song of the psalmist: “Holiness becometh thy house, O Lord, for ever.”[9] Thomas L. Kane, who visited Nauvoo in 1846, felicitously compared “the entablature of the front” to “a baptismal mark on the forehead.”[10]

Figure 4. Inscription on the reconstructed Nauvoo Temple[11]

Details of the inscription as it appears on the reconstructed Nauvoo Temple are shown here. The date of “April 6, 1841” that had been selected for the groundbreaking recalled the anniversary of the organization of the Church in 1830. Unlike the inscription above, the words on the original temple were gilded brightly.[12]

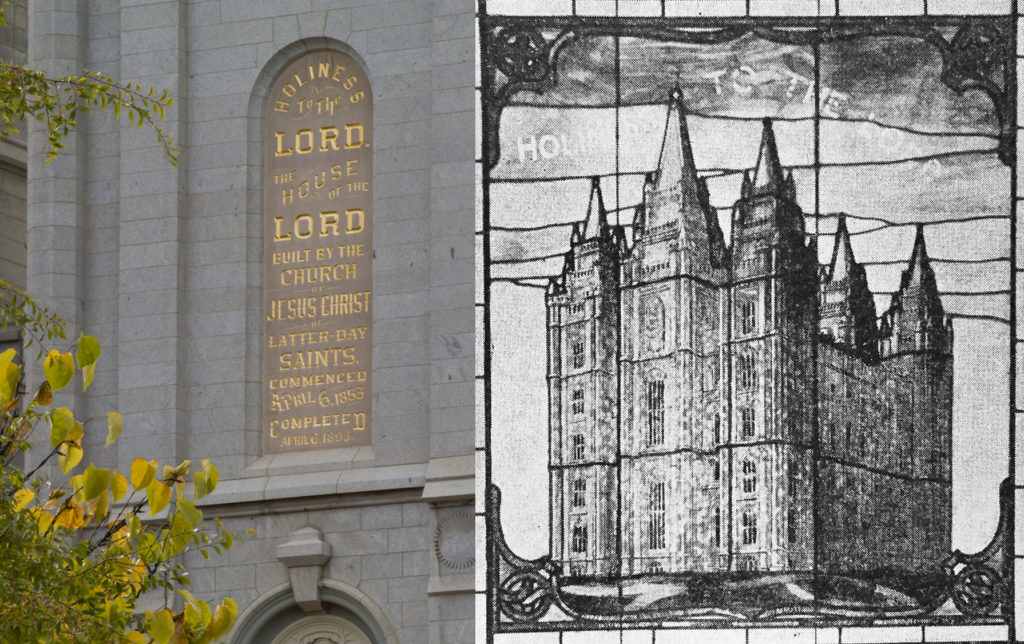

Figure 5a, b. a. Dedicatory inscription for the Salt Lake Temple.>[13] b. Detail from the memorial window adjoining the Council Room of the First Presidency and the Twelve, with the inscription “Holiness to the Lord” appearing as in the clouds above the building.[14] The inscription, “set beneath the cloud-stones, symbolizes the reality of the establishment of [God’s] kingdom on earth with the Temple as His personal sanctuary where heaven and earth are joined in a perfect order. It is also the place (as are any of the temples) where the inhabitants of Zion or those pure in heart can gather and be taught of light and truth. … A house … to which He may come or send His messengers, to confer priesthood and keys and to give revelation to His people.”[15]

Salt Lake City. The administration of Brigham Young encouraged a flowering of the use of “Holiness to the Lord.” The words appeared not only in plans for the dedicatory inscription of the Salt Lake Temple,[16] but throughout the entire territory of Deseret. As Elder D. Todd Christofferson described it:[17]

Figure 6: (top): sacrament goblet,[18] sacrament plate,[19] Seventy’s certificate of ordination;[20] (middle): Salt Lake City Fifteenth Ward Relief Society Hall with window banner,[21] hammer head,[22] drum;[23] (bottom): door knob on the Salt Lake Temple[24]; escutcheon with monogram (HTTL) on an outer door of the Salt Lake Temple[25]; 1860 Mormon five-dollar gold piece with “Holiness to the Lord” written in the Deseret Alphabet[26]

The pioneer Saints … affixed … “Holiness to the Lord,” on seemingly common or mundane things as well as those more directly associated with religious practice. It was inscribed on sacrament cups and plates and printed on certificates of ordination of Seventies and on a Relief Society banner. “Holiness to the Lord” also appeared over the display windows of Zion’s Cooperative Mercantile Institution, the ZCMI department store. It was found on the head of a hammer and on a drum. “Holiness to the Lord” was cast on the metal doorknobs of President Brigham Young’s home.

**

Figure 7. The "Deseret Stone," placed in the George Washington National Monument in Washington, D.C., photographed by Marsena Cannon, 19 March 1853[27]

Washington Monument. In response to an invitation to each state and territory of the United States, “the General Assembly of the provisional State of Deseret passed a resolution on 10 February 1851, approved by Utah Territorial Governor Brigham Young a few days later, to provide a block of marble to the Washington Monument.”[28] The principal illustrations on the stone were described by the First Presidency of the Church as “a Bee-hive, in full operation, in the centre, encircled by the convolvulus [i.e., the “twining plant with trumpet-shaped flowers”[29]], &c, with the inscription, ‘Holiness to the Lord. Deseret.'”[30]

The phrase “Holiness to the Lord” and the motif of the honeybee come from the Bible[31] and the Book of Mormon[32] respectively. Perhaps in this case, however, these elements were selected for the final design not only because they were distinctive identifiers for the Mormon religion and the territory of Deseret, but also because of their association with Freemasonry, a fraternal organization in which many of the Saints had participated in Nauvoo.[33] The use of these symbols might be seen as a tip of the hat to George Washington who, along with many other prominent and ordinary citizens of that era, was a Mason throughout his adult life.[34] It should also be mentioned that Brigham Young’s father, John Young, had served in three campaigns of the American Revolution under General George Washington.[35]

What had the phrase “Holiness to the Lord” come to mean to Brigham Young over his lifetime? Speaking in 1862 of his conversion, he said:[36] “Thirty years’ experience has taught me that every moment of my life must be holiness to the Lord, resulting from equity, justice, mercy, and uprightness in all my actions, which is the only course by which I can preserve the Spirit of the Almighty to myself.”

Figure 8. “Holiness to the Lord” appears on this window keystone of the Logan Utah Temple[37]

What was the meaning of “Holiness to the Lord” in the Old Testament?

Basic meaning of the Hebrew. The Hebrew equivalent of “Holiness to the Lord” is written as קדש ליהוה (kodesh le’YHWH):

- The first word, kodesh[38] (= “Holiness, holy”), has application here to something that is set apart from the world and is considered to be singled out as belonging exclusively to the Lord, often for temple purposes. Anything thus consecrated becomes sacrosanct, dedicated wholly to the Lord’s purposes and under His personal protection and care.

- The second word, le, can mean “to” or “for.” The thing or person referenced in the phrase is considered to be “holy to” or “holy for” the Lord.

- The Hebrew word (YHWH) for the common English form Jehovah is typically vocalized by modern scholars as Yahweh. Although the name is printed in the Hebrew Bible, observant Jews do not say it as it is written. Instead, as a matter of reverence, they substitute the word “Lord” (adonaï) when reading scripture.

Figure 9. Artist’s conception of the plate of pure gold that was to be worn on the forehead of the high priest, as described in Exodus 28:36-38; 39:30

How was the phrase used in the Old Testament? Briefly, it was applied to people, not to buildings. As mentioned above, the phrase “Holiness to the Lord” is never used in the Bible in connection with the temple itself. Instead, the Israelites were instructed to engrave these words on a “plate of pure gold” that was to be worn upon the forehead of high priests who had been consecrated to the Lord’s service through sacred ordinances.[39]

To wear the plate of pure gold engraved with “Holiness to the Lord” on the forehead was a divinely bestowed honor of the greatest significance and belonged solely to the high priest. It identified the high priest with the Lord Himself.[40] To further emphasize that those who enter into the “oath and covenant … [of] the priesthood”[41] today do so in similitude of the Son of God, note Margaret Barker’s description of how the concept of becoming a son of God relates both to ordinances in earthly temples and to actual ascents to the heavenly temple:[42]

The high priests and kings of ancient Jerusalem entered the Holy of Holies and then emerged as messengers, angels [i.e., emissaries] of the Lord. They had been raised up, that is, resurrected; they were sons of God, that is, angels; and they were anointed ones, that is, messiahs. … [By entering the Holy of Holies as part of temple service,] human beings could become angels, and then continue to live in the material world. This transformation did not just happen after physical death; it marked the passage from the life in the material world to the life of eternity.

Today, those who receive the higher temple ordinances also become, in their measure, emissaries of the Lord, “saviors of men,”[43] in likeness of ancient high priests and kings — and ultimately as their Redeemer.

Figure 10. Worshiping the high priest.

Speaking of the figurative heavenly journey that was enacted in ancient temple ordinances, Matthew Bowen has argued elsewhere that both the king and the high priest, emerging from the Holy of Holies, were seen and worshiped as Yahweh, the Lord.[44] Consistent with this identification, Alma 13 specifically states that high priests were ordained “in a manner that thereby the people might know in what manner to look forward to [God’s] Son for redemption.”[45] Moreover, the reason the ancient ordinances of the high priesthood associated with the temple were given was so “that thereby the people might look forward on the Son of God … for a remission of their sins.”[46]

At Sinai, the Lord told Moses that the day would come when all His people would obey His voice and keep His covenant, thus becoming “a kingdom of priests, and an holy nation” that belonged exclusively to Him.[47] A related scene involving a sealing in the forehead with the Father’s name is symbolically represented in Revelation 14:1:[48]

And I looked, and, lo, a Lamb stood on the mount Sion, and with him an hundred forty and four thousand, having his Father’s name written [sealed[49]] in their foreheads.

That day, when all God’s people will be sealed as saints indeed — fully sanctified and holy — is still in the future. This leads to a question about the here and now.

Why are members of the Church called “saints” even though they are not yet completely pure and holy? The short answer is that members of the Church are called saints because they have made covenants, not because they have already completed the process of sanctification. As James E. Faulconer explains:[50]

Holiness derives from being set apart, not from the character of the object in question. For example, the altar is holy because it has been set apart for use in the temple, not because it has a certain shape or is made of a particular material. Any use of the altar not in line with its prescribed use as a holy object is forbidden. Similarly Israel is holy because it is chosen, not the reverse. Being called and set apart for particular divine purposes makes Israel holy, and that holiness puts them under solemn and divine obligation, the obligation to live up to the holiness to which they have been set apart. …

That the Greek word for “saint” [hagios] indicates purity shows that there is more to being a saint, to taking Christ’s name upon ourselves, than membership in the formal organization of the Church. We become saints by being called and set apart for God’s purposes, and we remain saints by striving to meet the obligation of purity that such a calling entails. …

As [King] Benjamin makes clear,[51] Christ’s redemption and our humble submission to him makes us saints [in the ultimate sense]. … It is … presumptuous to declare any individual besides Christ to be a saint if we mean by that word “one who is pure.” However, if by calling ourselves saints we indicate our membership in the Church, our communion with the rest of those who intend to live as God’s people, and our calling to the service of God, it is not presumptuous to claim to be saints.[52]

What is the purpose of modern temples?

We need to become a holy people. The Lord has commanded: “Be ye holy, for I am holy.”[53] The purpose of the temple is to help every person who enters therein to become holy in likeness of the Holy One and the house that bears His name. The Apostle Paul reminded the Saints of the connection between the temple building and our own selves when he wrote:[54]

Know ye not that ye are the temple of God, and that the Spirit of God dwelleth in you? … The temple of God is holy, which temple ye are.

In 2001, President Russell M. Nelson elaborated on the importance of becoming a holy people, worthy and prepared to enter the temple:[55]

Those who enter the temple are also to bear the attribute of holiness.[56] It may be easier to ascribe holiness to a building than it is to a people. We can acquire holiness only by enduring and persistent personal effort. Through the ages, servants of the Lord have warned against unholiness. Jacob, brother of Nephi, wrote: “I would speak unto you of holiness; but as ye are not holy, and ye look upon me as a teacher, [I] must … teach you the consequences of sin.”[57] …

As temples are prepared for our members, our members need to prepare for the temple.

Figure 11. James Tissot: Dedication of Solomon’s temple

We need to take upon ourselves the name of the Lord. The dedicatory prayer for Solomon’s temple stressed that it was not meant to be a residence for God, since He “lived in his ‘dwelling place in heaven’ but that the ‘name of God’ dwelt in the Temple.”[58] In that temple, the final “gate of the Lord, into which the righteous shall enter,”[59] very likely referred to “the innermost temple gate,”[60] where those “seeking the face of the God of Jacob”[61] would find the fulfillment of their temple pilgrimage. This final gate was associated with the name of God Himself.

With this idea in mind, the shout of the people at Christ’s triumphal entry becomes more understandable. Margaret Barker suggested that their words might be translated as “Blessed is he who comes with [rather than in] the Name of the Lord.”[62] Consistent with this translation, such a cry, coupled with the plea of “Hosanna” (literally “save us now”!), could be taken as an acknowledgement of Jesus’ role as the Messiah, the great High Priest, one who, figuratively speaking, had the Divine Name sealed on His forehead[63] and could bring those who were willing and fit to follow Him into the presence of God. In the process of time, each “disciple” could, through obedience and diligence, become “as his master,” and each “servant as his lord.”[64]

For Latter-day Saints, the blessing on the sacrament bread foreshadows that supernal hope as it anticipates the fulness of temple blessings. Elder David A. Bednar, citing President Dallin H. Oaks, explained that:[65]

in renewing our baptismal covenants by partaking of the emblems of the sacrament, “we do not witness that we take upon us the name of Jesus Christ. [Rather], we witness that we are willing to do so.[66] The fact that we only witness to our willingness suggests that something else must happen before we actually take that sacred name upon us in the [ultimate and] most important sense.”[67] The baptismal covenant clearly contemplates a future event or events and looks forward to the temple.

Figure 12. The Democratic Republic of the Congo Kinshasa Temple

The teachings of President Oaks and Elder Bednar above came to mind as I contemplated a particular event that took place during the construction of the DR Congo Kinshasa Temple. At the time, my wife and I were living in an apartment directly across the street from the construction site. We watched with interest from our apartment building as work on the temple progressed. We passed its future entrance regularly at an even closer range while walking to our meetinghouse, which sat on the same piece of property.

Like some other reflections I have had about the temple over the years, this one came as I thought specifically about the difference between English and French versions of temple-related phrases. Through these experiences I have come to agree with the observation of an eminent scholar of translation, Walter Benjamin, that a good “translation transplants the original into a more definitive linguistic realm.”[68] In other words, sometimes, ironically, a translation may promote a better understanding of the original, in effect allowing “the pure language [that is beyond any particular language], as though reinforced by its own medium, to shine upon the original all the more fully.”[69]

Figure 13. Culminating work begins around the Kinshasa Temple doorway

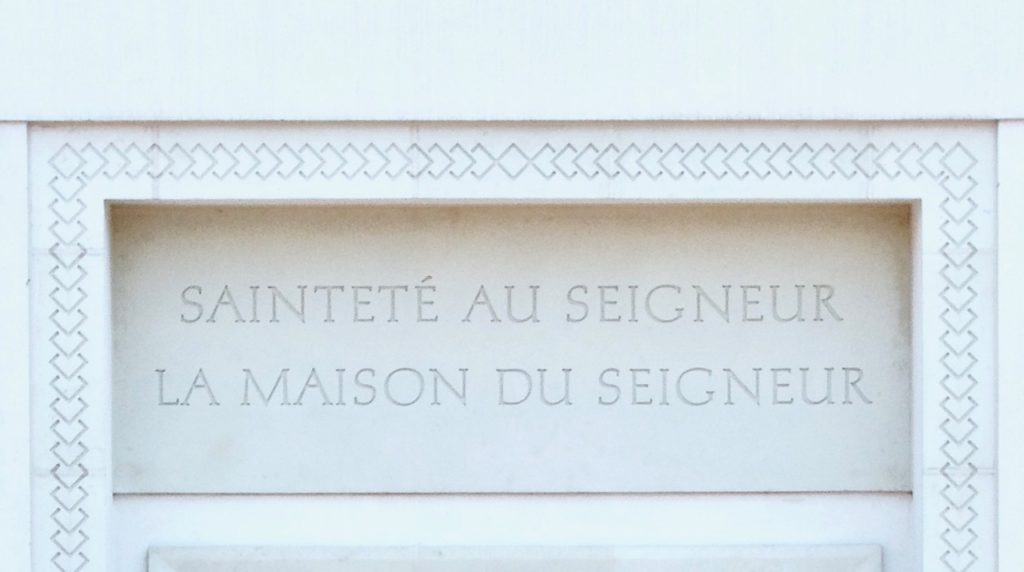

In describing the use of the phrase “Holiness to the Lord” on LDS temples, President Russell M. Nelson mentioned that “translated equivalents are used on temples throughout the world.”[70] Since I was familiar with the translation of the phrase in the Louis Segond Bible that is used by the Church in French-speaking countries, I had already imagined that the inscription on the Kinshasa temple would read a little differently than in English, namely as “Sainteté à l’Éternel” (= “Holiness to the Eternal One”). Imagine our anticipation as we saw the culminating work begin around the doorway in preparation for the inscription plaque.

Figure 14. Kinshasa Temple inscription: “Holiness to the Lord — The House of the Lord,” consistent with the English King James Translation

However, when the long-awaited inscription finally appeared, it was not what I had expected. Instead of reading “Sainteté à l’Éternel” (= “Holiness to the Eternal One”), it followed a literal translation of the English King James Version, namely “Sainteté au Seigneur” (= “Holiness to the Lord”).[71]

At first, I was surprised. The translation “Holiness to the Eternal One” seemed to embody a more appropriate and specific description of God because the Old Testament name of the Lord is usually taken as signifying that God is eternal — that He is and always will be.[72]

But as I reflected further I came to realize that trying to describe God by means of only a particular, more specific name can limit one’s worship, since “every name is an attribute and all names refer to divine manifestations and qualities [e.g., His eternal nature] rather than to His ineffable essence.”[73] For this reason, many religions delight in studying all of the various names of God together while at the same time looking forward to the day when “there [shall] be one Lord, and his name one.”[74]

I also began to think about the sacred nature of the names of Deity, that they should be spoken in awe and reverence and should not be the subject of “too frequent repetition.”[75] The word “Lord” (adonaï) was the one adopted by the Jews as a substitute for speaking the personal name of God. As the single exception to the general rule in Jewish law that the divine name should not be spoken, it was solemnly pronounced in a low voice by the High Priest standing in the most holy place of the temple only once a year, on the Day of Atonement. At the moment that name was spoken, according to the Mishnah, all the people were to fall on their faces.[76]

Even though the word “Lord” is a limiting description in its own way, I began to feel that I could not think of a better word to characterize my relationship to Him as I consecrate myself anew each time I go to the temple. He is my Lord because I belong to Him; because I am bound to Him in a covenant relationship; and because for the blessings of life and salvation I am “indebted unto him, … and will be, forever and ever.”[77] According to Moses 5:4, and consistent with some strands of rabbinic tradition,[78] this was the name Adam and Eve used as they “called upon the name of the Lord” in the fallen world.

Figure 15a, b. “My name shall be there.” Congolese Primary children were invited to write their name on small stones, hand-cut from the Congo River and painted white, to be embedded within the concrete of the Kinshasa Temple. The children shown at right belong to the Buima Branch in Bas Congo

Moreover, the fact that the English word “Lord,” like the Hebrew adonaï, is meant in everyday usage to stand for the divine name rather than being the divine name itself reminds me of God’s declaration when He said, in reference to the temple: “My name shall be there.”[79]

Figure 16. ZCMI Co-op Store displaying a “Holiness to the Lord” motto[80]

The Why

The ubiquitous use of “Holiness to the Lord” in pioneer times served as a constant reminder of the future day prophesied by Zechariah when every person and everything on earth — even the “bells of the horses” — would be fit to bear the inscription “Holiness unto the Lord.”[81]

Hugh Nibley, whose life spanned from the end of pioneer times to the modern day, became a sad witness of how the proliferation of holiness prophesied by Zechariah became a more distant reality as he grew older. He laments:[82]

The greatest change I have noticed in the fifty years since I used to make the three-day bus trip from Los Angeles to Salt Lake is the absence of that thrill I felt when the golden words would begin to appear on the buildings of every little town: “Holiness to the Lord,” over-arching the all-seeing eye that monitors the deeds of men. That inscription was the central adornment of every important building, including each town’s main store — the Co-op, as committed as any other institution of the Church to the plan of holiness. Next to that, what moved me most was the sight of the St. George Temple in its beautiful oasis.

What became of “holiness”? Did it pass away with all the noble pioneer monuments all along the highway, wiped out by the relentless demands of a bottom-line economy? Those delightful old stakehouses, bishop’s storehouses, schools, wardhouses, homes, and even barns have been steadily replaced by service stations, chain restaurants, shopping malls, motels, and prefabricated functional church and school buildings right from the assembly line: admittedly more practical, but must every house and tree and monument be destroyed because it does not at present pay for itself in cold cash? The St. George Temple is now lost in a neon jungle and suburban tidal-wash of brash, ticky-tacky commercialism. One can only assume that it bespeaks the spirit of our times. God has said that the Saints must build Zion with an eye to two things, holiness and beauty: “For Zion must increase in beauty and in holiness”[83] — with no qualifying provision, “Insofar as an adequate return on the investment will allow.”

Everything in Zion is to be holy, for God has called it “My Holy Land,” and that with a dire warning: “Shall the children of [Zion] … pollute my holy land?”[84] Apparently it is possible. Holy things are not for traffic; they are not negotiable: “Thy money perish with thee, because thou hast thought that the gift of God may be purchased with money.”[85] Things we hold sacred we do not sell for money. Consequently, to become commodities of trade, the land of Zion and what is in it must be de-sanctified. … [T]he land of Zion must become un-holy (what was con-secrated must be de-secrated) before it can be used for gain. …

Time and again the Saints have made a bungle of the superstructure, unwilling to conform to the foundation laid down in the beginning. When I first came to Utah in the 1940s, it was a fresh new world, a joy and a delight to explore far and wide with my boys and girls. But now my friends no longer come on visits as they once did, to escape the grim commercialism and ugly litter of the East and the West Coast. We can watch that now on the Wasatch Front. The Saints no longer speak of making the land blossom as the rose, but of making a quick buck in rapid-turnover real estate. … The students I have talked with at the beginning of this semester … are not interested in improving their talents but in trafficking in them.

Though the glory and holiness of God’s presence no longer fills the whole earth as it did at Creation, it has never been completely withdrawn. In a movement similar to the divine concealment that the Lurianic kabbalah terms “contraction,”[86] the fulness of God’s glory is, as it were, concentrated in one place — the Temple — which continues to represent in microcosm the image of what will someday again become the model for a fully renewed Creation, happy in the divine rest of an eternity of Sabbaths.[87] Until that day, however, the Temple remains “to space what the Sabbath is to time, a recollection of the protological dimension bounded by mundane reality. It is the higher world in which the worshiper wishes he could dwell forever. … The Temple is the moral center of the universe, the source from which holiness and a terrifying justice radiate”[88] to the dark and fallen world that surrounds it.

Fittingly, just as the first book of the Bible, Genesis, recounts the story of Adam and Eve being cast out from the Garden, its last book, Revelation, prophesies a permanent return to Eden for the sanctified.[89] In that day, the veil that separates man and the rest of fallen creation from God will be swept away, and all shall be “done in earth, as it is in heaven.”[90] In the original Garden of Eden, “there was no need for a temple — because Adam and Eve enjoyed the continual presence of God” — likewise, in John’s vision “there was no temple in the Holy City, ‘for its temple is the Lord God.'”[91]

May we heed the words of President Russell M. Nelson calling us to greater holiness, not only as “personal preparation for temple blessings,” but also for the eventual return of the heavenly kingdom presaged by that Holy House.

My gratitude for the love, support, and advice of Kathleen M. Bradshaw on this article. Links to the originals of some of the photos above were helpfully provided on http://thetrumpetstone.blogspot.com/2012/02/holiness-to-lord-house-of-lord.html. Thanks also to R. Jean Addams, Marcel Kahne, Stephen L. Ricks, Jonathon M. Riley, and Stephen T. Whitlock for valuable comments and suggestions.

Further Study

A video version of this article is available on the Interpreter Foundation and FairMormon YouTube channels at https://youtu.be/ruSTv7-8w7U.

Video of President Nelson’s April 2001 General Conference talk “Personal Preparation for Temple Blessings” at https://churchofjesuschrist.org/general-conference/2001/04/personal-preparation-for-temple-blessings?lang=eng

For other scripture resources relating to this lesson, see The Interpreter Foundation Old Testament Gospel Doctrine Index (https://interpreterfoundation.org/gospel-doctrine-resource-index/ot-gospel-doctrine-resource-index/) and the Book of Mormon Central Old Testament KnoWhy list (https://knowhy.bookofmormoncentral.org/tags/old-testament).

References

Alexander, T. Desmond. From Eden to the New Jerusalem: An Introduction to Biblical Theology. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel, 2008.

American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (Fourth Edition, 2000). In Bartleby.com. http://www.bartleby.com/61/. (accessed April 26, 2009).

Arrington, Leonard J. Brigham Young: American Moses. New York City, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1985.

Barker, Margaret. The Revelation of Jesus Christ: Which God Gave to Him to Show to His Servants What Must Soon Take Place (Revelation 1.1). Edinburgh, Scotland: T&T Clark, 2000.

———. The Hidden Tradition of the Kingdom of God. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), 2007.

———. Christmas: The Original Story. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 2008.

Bednar, David A. "Honorably hold a name and standing." Ensign 39, May 2009, 97-100.

Benjamin, Walter. 1923. "The task of the translator." In Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, Volume 1: 1923-1926, edited by Marcus Bullock and Michael W. Jennings. Translated by Harry Zohn, 253-63. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1996.

Bowen, Matthew L. "’They came and held Him by the feet and worshipped Him’: Proskynesis before Jesus in Its biblical and Ancient Near Eastern context." Studies in the Bible and Antiquity 5 (2013): 63-89.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. "Standing in the Holy Place: Ancient and modern reverberations of an enigmatic New Testament prophecy." In Ancient Temple Worship: Proceedings of the Expound Symposium, 14 May 2011, edited by Matthew B. Brown, Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, Stephen D. Ricks and John S. Thompson. Temple on Mount Zion 1, 71-142. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014. http://www.templethemes.net/publications/04-Ancient%20Temple-Bradshaw.pdf.

———. Temple Themes in the Oath and Covenant of the Priesthood. 2014 update ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014.

———. "Freemasonry and the Origins of Modern Temple Ordinances." Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 15 (2015): 159-237. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/freemasonry-and-the-origins-of-modern-temple-ordinances/. (accessed May 20, 2016).

———. "What did Joseph Smith know about modern temple ordinances by 1836?”." In The Temple: Ancient and Restored. Proceedings of the 2014 Temple on Mount Zion Symposium, edited by Stephen D. Ricks and Donald W. Parry. Temple on Mount Zion 3, 1-144. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2016.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and Matthew L. Bowen. "”By the Blood Ye Are Sanctified”: The Symbolic, Salvific, Interrelated, Additive, Retrospective, and Anticipatory Nature of the Ordinances of Spiritual Rebirth in John 3 and Moses 6." Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 24 (2017): 123-316. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/by-the-blood-ye-are-sanctified-the-symbolic-salvific-interrelated-additive-retrospective-and-anticipatory-nature-of-the-ordinances-of-spiritual-rebirth-in-john-3-and-moses-6/. (accessed January 10, 2018).

Brooke, John L. The Refiner’s Fire: The Making of Mormon Cosmology, 1644-1844. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Brown, Francis, S. R. Driver, and Charles A. Briggs. 1906. The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2005.

Brown, Lisle G. 1999. Interior description of the Nauvoo Temple. In The Nauvoo Temple: The House of the Lord. http://users.marshall.edu/~brown/nauvoo/interior.html. (accessed July 4, 2018).

———. 1999. Nauvoo Temple exterior symbolism. In The Nauvoo Temple: The House of the Lord. http://users.marshall.edu/~brown/nauvoo/symbols.html. (accessed August 31, 2014).

Christofferson, D. Todd. "The living bread which came down from heaven." Ensign 47 2017, 36-39. https://churchofjesuschrist.org/general-conference/2017/10/the-living-bread-which-came-down-from-heaven?lang=eng. (accessed July 4, 2018).

Clark, James R., ed. Messages of the First Presidency. 6 vols. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1965-1975.

Draper, Richard D., and Donald W. Parry. "Seven promises to those who overcome: Aspects of Genesis 2-3 in the seven letters." In The Temple in Time and Eternity, edited by Donald W. Parry and Stephen D. Ricks, 121-41. Provo, UT: The Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS) at Brigham Young University, 1999.

Faulconer, James E. The Life of Holiness: Notes and Reflections on Romans 1, 5-8. Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, Brigham Young University, 2012.

Faust, James E. "Standing in holy places." Ensign 35 2005, 62-68. https://churchofjesuschrist.org/general-conference/2005/04/standing-in-holy-places?lang=eng. (accessed July 4, 2018).

General Board of Relief Society. History of Relief Society, 1842-1966. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret News Press, 1966.

Hamblin, William J., and David Rolph Seely. Solomon’s Temple: Myth and History. London, England: Thames & Hudson, 2007.

Hamblin, William J. "The sôd of YHWH and the endowment." Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 4 (2013): 147-53. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/the-sod-of-yhwh-and-the-endowment/. (accessed April 19, 2013).

Hamilton, C. Mark. The Salt Lake Temple: A Monument to a People. 5th ed. Salt Lake City, UT: University Services Corporation, 1983.

Holzapfel, Richard Neitzel, and Paul H. Peterson. "Setting the record straight (visual images)." Journal of Mormon History 26, no. 2 (2000): 215-22. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1035&context=mormonhistory. (accessed July 6, 2018).

Immekus, Alexander. Freemasonry. In George Washington’s Mount Vernon. https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/freemasonry/. (accessed July 7, 2018).

Kane, Thomas L. The Mormons: A DIscourse Delivered Before the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, March 26, 1840. Philadlephia, PA: King and Baird, 1850. https://archive.org/details/mormonsdiscourse00kane. (accessed July 6, 2018).

Kimball, Heber Chase. On the Potter’s Wheel: The Diaries of Heber C. Kimball. Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books, 1987. https://archive.org/details/OnThePottersWheelHeberKimball. (accessed July 6, 2018).

Koehler, Ludwig, Walter Baumgartner, Johann Jakob Stamm, M. E. J. Richardson, G. J. Jongeling-Vos, and L. J. de Regt. The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament. 4 vols. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 1994.

Levenson, Jon D. "The temple and the world." The Journal of Religion 64, no. 3 (1984): 275-98. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1202664. (accessed July 2).

Madsen, Truman G. 1994. "The temple and the mysteries of godliness." In The Temple: Where Heaven Meets Earth, 25-37. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2008.

Marmorstein, A. 1920-1937. The Doctrine of Merits in Old Rabbinical Literature and The Old Rabbinic Doctrine of God (1. The Names and Attributes of God, 2. Essays in Anthropomorphism) (Three Volumes in One). New York City, NY: KTAV Publishing House, 1968.

McBride, Matthew. A House for the Most High: The Story of the Original Nauvoo Temple. Draper, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007.

Mowinckel, Sigmund. 1962. The Psalms in Israel’s Worship. 2 vols. The Biblical Resource Series, ed. Astrid B. Beck and David Noel Freedman. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2004.

Nelson, Russell M. "Personal preparation for temple blessings (from a talk in the April 2001 General Conference of the Church)." In Hope in Our Hearts, edited by Russell M. Nelson, 101-10. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2009. https://churchofjesuschrist.org/general-conference/2001/04/personal-preparation-for-temple-blessings?lang=eng. (accessed July 7, 2018).

Neusner, Jacob, ed. The Mishnah: A New Translation. London, England: Yale University Press, 1988.

Nibley, Hugh W. 1980. "How firm a foundation! What makes it so." In Approaching Zion, edited by D.E. Norton. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 9, 149-77. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1989.

Oaks, Dallin H. "Taking upon us the name of Jesus Christ." Ensign 15, May 1985, 80-83. https://churchofjesuschrist.org/general-conference/1985/04/taking-upon-us-the-name-of-jesus-christ?lang=eng. (accessed October 22, 2016).

Parry, Donald W. "Temple worship and a possible reference to a prayer circle in Psalm 24." BYU Studies 32, no. 4 (1992): 57-62.

Salt Lake City Fifteenth (15th) Ward Relief Society Hall p. 1. In Utah Department of Heritage and Arts Classified Photographs. https://collections.lib.utah.edu/details?id=435674. (accessed July 7, 2018).

Sarna, Nahum M., ed. Exodus. The JPS Torah Commentary, ed. Nahum M. Sarna. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society, 1991.

Scholem, Gershom, ed. 1941. Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism. New York City, NY: Schocken Books, 1995.

Schwartz, Howard. Tree of Souls: The Mythology of Judaism. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Smith, Joseph, Jr. 1902-1932. History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Documentary History). 7 vols. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1978.

———. 1938. Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1969.

Talmage, James E. The House of the Lord. Salt Lake City, Utah: The Deseret News, 1912. https://archive.org/stream/houseoflordstudy00talm#page/n0/mode/2up. (accessed August 5, 2014).

———. 1912. La Maison du Seigneur. Translated by Marcel Kahne. Torcy, France: Église de Jésus-Christ des Saint des Derniers Jours, 1982. http://www.lafeuilledolivier.com/Fac_similes/La_maison_du_Seigneur_ed_2.pdf. (accessed July 8, 2018).

Temple (LDS Church). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Temple_(LDS_Church). (accessed July 4, 2018).

Young, Brigham. 1859. "Remarks by President Brigham Young, made in the Tabernacle, Great Salt Lake City, Sunday p.m., 31 July 1859." In Journal of Discourses. 26 vols. Vol. 6, 342-49. Liverpool and London, England: Latter-day Saints Book Depot, 1853-1886. Reprint, Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1966.

Endnotes

At half 11 we have one thing Laken [lacking] in the House of the Lord, that is a stone in the wast [west] End fore [the] super cription. Holyness to the Lord. Rote a leter to the Architect.”

Although John Brooke (J. L. Brooke, Refiner’s Fire, p. 249) mistakenly took a statement by Joseph Smith to “the Holiest of Holies” (J. Smith, Jr., Documentary History, 1 May 1842, 4:608) as an out-of-context reference to the Nauvoo Temple, the Prophet actually and appropriately was making an allusion to the heavenly temple where God the Father resides (see J. M. Bradshaw, Temple Themes in the Oath, pp. 197-200 n. 398).

In 1833, a committee chaired by U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall, began efforts to raise money for the erection of a monument honoring George Washington. It was a lengthy project. The cornerstone-laying ceremonies occurred on 4 July 1848, but it was not dedicated until 21 February 1885. During this almost thirty-seven year period, several groups, organizations, and agencies attempted to move the project along. During the process, an invitation was sent to each state and territory, inviting each to contribute a stone from its region. In response, the General Assembly of the provisional State of Deseret passed a resolution on 10 February 1851, approved by Utah Territorial Governor Brigham Young a few days later, to provide a block of marble to the Washington Monument. When a good specimen of marble could not be located, oolytic limestone quarried near Manti, Sanpete County, Utah, was substituted. William Ward prepared the stone, measuring three feet long, two feet wide, and six and a half inches thick.

When completed, Church leaders asked Marsena Cannon to photograph the stone before sending it off to Washington, D.C. The Historian’s Office Journal notes: "Saturday 19 [March 1853] Clear fine da[y]… Mr. Cannon took a daguerreotype picture of the Deseret block of sculptured marble intended for the Washington Monument." T. W. Ellerebeck, a clerk in the office, also noted in his diary, "19 March 1853. Bro. Cannon taking Daguerotype [sic] of the Tithing Store and of the Stone for the Washington Monument." There is no indication that the stone had any relationship to the Salt Lake Temple’s cornerstone laid on 6 April 1853. There is no contemporary reference to the temple cornerstone as being anything but simple cut stone without any symbolic inscriptions or designs.

Three months later, the Deseret Stone was transported to Washington, D.C, partly by wagon, in June 1853, under the direction of Philemon C. Merrill. The Washington National Monument Society received the stone on 27 September 1853. The stone was still in a storage shed in early 1885. It was placed at the 200-foot level of the monument some time later. (Work continued on the monument after it was dedicated.)

… signifies sealing the blessing upon their heads, meaning the everlasting covenant, thereby making their calling and election sure.

The phrase “called to be saints” [in Romans 1:7] literally means “called saints,” with the word “called” as an adjective. As we have just seen, the saints in Rome are saints by virtue of their calling, not by virtue of their purity.

The meaning of being “willing to take upon [us] the name of Jesus Christ” in the sacrament is clear in light of temple ordinances (D. H. Oaks, Taking Upon Us; D. A. Bednar, Name, p. 98; D&C 20:77; 109:22, 26, 79). Truman G. Madsen writes: “You are required as disciples of Christ to come once in seven days and covenant anew to take upon you the name of Jesus Christ. In the house of the Lord you come to take upon you His name in the fullest sense” (T. G. Madsen, Temple and Mysteries, p. 33).

… the servants of God-and-the-Lamb (a unity) worship Him in the place where the Lord God is their Light, and they have His Name on their foreheads. In other words, they have been admitted to the Holy of Holies/Day One, and they bear on their foreheads the mark of high priesthood, the Name …

The theme of God’s disclosure of His own name to those who approach the final gate to enter His presence is reminiscent of the explanations of Facsimile 2 from the book of Abraham that date to sometime between 1835 and 1841.88 In Figure 7 of that facsimile, God is pictured as “sitting upon his throne, revealing through the heavens the grand Key-words of the Priesthood.” A similar concept is present in Islam. For more on this topic, see J. M. Bradshaw, What Did Joseph Smith Know, pp. 12-15.

The names … have a paradoxical function. They represent something which they are not, and hence they separate us from the reality which they represent. At the same time they also join us to that reality to which, otherwise, we could have no contact at all. In fact, they not only “represent,” but to the extent their opaqueness can become transparent they also “reveal.” …

For the medieval kabbalists the whole of the Torah was a mysterious combination of “Names of God”; in fact, the Torah “is nothing but the one great and holy Name of God” (G. Scholem, Trends, p. 210).

[89] Revelation 22:1-5. See M. Barker, Revelation, pp. 327-333; R. D. Draper et al., Promises; T. D. Alexander, From Eden, pp. 13-15.

In cultic contexts, the term for “glory” (kabod) has a technical meaning; it is the divine radiance… that manifests the presence of God [cf. Exodus 40:34, 1 Kings 8:11]… If my translation of Isaiah 6:3 is correct, then the seraphim identify the world in its amplitude with this terminus technicus of the Temple cult. As Isaiah sees the smoke filling the Temple, the seraphim proclaim that the kabod fills the world (verses 3-4). The world is the manifestation of God as He sits enthroned in His Temple. The trishagion is a dim adumbration of the rabbinic notion that the world proceeds from Zion in the same manner that a fetus, in rabbinic etymology, proceeds from the navel.