This series is cross-posted with the permission of Book of Mormon Central

from their website at Pearl of Great Price Central

Audio Player

Figure 1. Bas-relief showing Ashurbanipal, King of Assyria, stabbing a wounded lion, North Palace, Nineveh, Mesopotamia, Iraq, ca. 645-635 BCE

The defeat of the gibborim

A previous Essay[1] described how the gibborim sorrowed and trembled after Enoch read their wicked deeds out of the book of remembrance and tendered the possibility of repentance. Drawing jointly on the Manichaean and Qumran accounts, Matthew Goff conjectures that the Book of Giants follows a set of Jewish traditions where at least some of the nephilim and gibborim “are not killed in a flood but rather have long lives.”[2] However, any conjectured move of at least some of the gibborim toward repentance was short-lived. Eventually, when Enoch’s enemies began to attack, they were roundly defeated, as we read in the Book of Moses:[3]

And so great was the faith of Enoch that he led the people of God, and their enemies came to battle against them; and he spake the word of the Lord, and the earth trembled, and the mountains fled, even according to his command; and the rivers of water were turned out of their course; and the roar of the lions was heard out of the wilderness; and all nations feared greatly, so powerful was the word of Enoch, and so great was the power of the language which God had given him.

As shown in the following translation by Edward Cook, significant details of the victory of Enoch and the people of God are echoed in the Book of Giants, including the mention of “the wild man”[4] and “the wild beast(s)”:[5]

3. [ … I am] mighty, and by the mighty strength of my arm and my own great strength

4. [and I went up against a]ll flesh, and I made war against them; but I did not

5. [prevail, and I am not] able to stand firm against them, for my opponents

6. [are angels who] reside in [heav]en, and they dwell in the holy places [ … ] And they were not

7. [defeated, for they] are stronger than I. [ … ]

8. [ ] of the wild beast has come, and the wild man they call [me.]

The roar of the wild beasts

The puzzling phrase “[ ] of the wild beast has come” immediately follows the description of the battle. The first portion of the phrase, indicated by brackets in Cook’s translation above, has proven difficult for other translators to reconstruct as well. Thus, for example, Loren Stuckenbruck renders it simply as two untranslated letters: “rh” (i.e., “rh of the beasts of the field is coming”[6]). However Martinez and Milik, less conservative in their willingness to make a conjecture, respectively understand the phrase as “the roar of the wild beasts has come”[7] and “the roaring of the wild beasts came.”[8] Lending credence to their reading, the Enoch account in the Book of Moses has a remarkably similar phrase: “the roar of the lions was heard.”[9] This phrase, placed in a nearly identical context that follows the description of the battle, is one of the most striking and unexpected affinities between Joseph Smith’s Enoch story and the ancient Book of Giants.

| Stuckenbruck Translation | Martinez Translation | Milik Translation | Moses 7:13 |

| rh of the beasts of the field is coming | the roar of the wild beasts has come | the roaring of the wild beasts came | the roar of the lions was heard |

Brian R. Doak’s sociolinguistic analysis reveals a convincing rationale for the author of the Book of Giants having placed these references together, giving an Old Testament example where victory against an elite adversary (in this case, a giant) and an prestige animal (lion) were also deliberately juxtaposed.[10] Yet, while there was indeed a close connection in ancient times between a military victory and “the roar of wild beasts,” that association would likely have been just as unfamiliar to Joseph Smith as it is to non-specialist readers today.

Figure 2. Fragmentary lion hunting scene from Uruk, Iraq, Iraq Museum, Baghdad, Iraq, ca. 3200 BCE. The scene shows “a bearded figure wearing a diadem that appears twice; one at the top killing a lion with a spear and once below killing lions with bow and arrow.”

Nimrod as an exemplar of a “wild man” who hunted “wild beasts”

To better interpret the “wild beast” motif, the importance of royal lion hunts in the ancient Near East must be understood. Note first that the evidence for these practices goes back to the primeval times in which Enoch lived, as in the scene from Uruk above. About the significance of lion hunting in this milieu, Doak observes:[11]

Ancient Mesopotamian kings routinely bragged of their hunting exploits, the prey being exotic animals in faraway lands; the Assyrian royal lion hunt represents the apex of this tradition insofar as it has been passed down to us visually.

Nimrod is one of the clearest biblical exemplars of this tradition. Described in the King James Bible, like Enoch’s opponents, as a “mighty one”[12] (Hebrew gibbor) and as a “mighty hunter”[13] (Hebrew gibbor tsayid), his prowess in pursuing and subduing his prey was legendary. According to Robert Kawashima:[14]

Nimrod’s exploits call to mind the famous monumental reliefs of the royal hunt scenes—discovered at Nineveh and housed in the British Museum—and the epic hero Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, who is immortalized in epic for slaying Humbaba and the Bull of Heaven[15] and for constructing the monumental walls of Uruk.

In his biblical role, Nimrod is presented to us as a proud archetype of Mesopotamian civilization that will be satirized in the story of the Tower of Babel,[16] and is even sometimes described as a “giant”:

It should be noted that postbiblical lore [invested] Nimrod with giant status and associated him with the building of the Tower of Babel in Genesis 11:1–5 (probably due to Nimrod’s association with Shinar). Furthermore, the Greek translation of gibbor as “Giant” in Genesis 10:8–9 attests to what may have been a popular, and not altogether illogical, interpretation that Nimrod’s stock as a giant somehow was passed through Noah, thus manifesting the hubris with which giants are often associated in his act of founding several cities[17] and inciting the Tower of Babel project.[18]

Of course, the brother of Jared, who may have been a contemporary of Nimrod, is also described as “a large and mighty man,”[19] as were, apparently, many of the Jaredite people.[20] However, notwithstanding the apparent “might” of men such as Nimrod and the brother of Jared, consistent with arguments made in a previous Essay,[21] it is probably a mistake to equate the gibborim (mighty warriors) with the nephilim (giants). Relative to Nimrod, Doak emphasizes:[22]

The reference to Nimrod as the first gibbor[23] immediately brings to mind the earlier invocation of the “gibborim of old” in Genesis 6:4, and it is noteworthy that the Bible provides here a prototype of all gibborim in the figure of Nimrod. Though it is not clear that Nimrod is a “giant,” [some] lines of interpretation suggest that Nimrod was thought to be something greater than an ordinary human.

In brief, Nimrod’s status as both a “mighty one”[24] (gibbor) and a “mighty hunter”[25] (gibbor tsayid) seem to depict him as a personification of the same “wild man” and “wild beast” hero ideals that Enoch’s proud opponents strove to emulate. Moreover, the resemblance of Nimrod to the gibborim of Enoch’s day extends to their similar refusal to accept God as their master. Nimrod, like the opponents of Enoch and Noah, is presented as the spiritual progenitor of those who sought to make a name for themselves[26] by building the Tower of Babel. In the gibborim culture, as in the culture of heroes throughout history:[27]

flesh is elevated above spirit, and the “name” of humanity is elevated above the “name” of God. In contrast to these heroes [stand Noah and Enoch], who [are] unique because [they have] found favor in the eyes of God.[28] [They do] not achieve a “name” through strength and power, but through [their] relationship with God.

Converging parallels in ancient sources and the Book of Moses

Bringing together the various threads running through ancient sources and the Book of Moses, Joseph Angel provides an additional piece of evidence by pointing out the association between the wild man, the lion, and the tree stump in the Book of Daniel and Nebuchadnezzar’s twin inscriptions at Wadi Brisa in northern Lebanon. “These two texts sit across from one another on the facing slopes of a river bed and are accompanied by partially preserved images of the king.”[29]

Figure 3. Bas-relief depicting Nebuchadnezzar battling a lion, west side of Wadi Brisa

The bas-relief on the west side shows Nebuchadnezzar battling a lion.

Figure 4. Bas-relief showing Nebuchadnezzar standing in front of a tall tree with no leaves, east side of Wadi Brisa

The facing bas-relief on the east “shows him standing in front of a tall tree with no leaves, perhaps a dead cedar. In the accompanying inscription, the Babylonian monarch speaks of the ‘strong cedars that I cut with my pure hands in the Lebanon.’”[30]

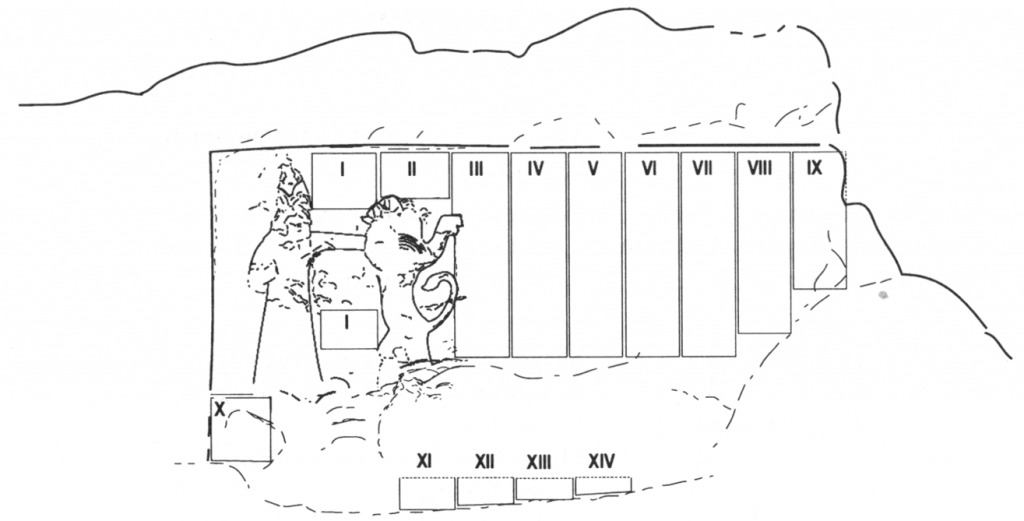

| Motifs | Nebuchadnezzar Reliefs (pro-Nebuchadnezzar) |

Book of Daniel (anti-Nebuchadnezzar) |

Book of Giants (anti-gibborim) |

Moses 6-7 (anti-gibborim) |

|

| Destruction of the wicked | Cedar tree hewn down, representing his subjugation of rival rulers | Dream of tree that is hewn down, representing subjugation of Nebuchadnezzar (4:10–27) | Dream of trees that are burned, representing death of all but Noah’s family in the Flood (4Q530, Fragment 2) | Vision of the death of the wicked in the Flood (Moses 7:43) | |

| Wild man | Nebuchadnezzar slays lion and cuts down tree, attesting to his status as a “wild man” | Nebuchadnezzar, abased by Daniel’s God, becomes animal-like “wild man” (4:31–33) | Leader of gibborim, abased by Enoch’s God, becomes animal-like “wild man”; Enoch’s people prove “stronger” than him because they are “angels” (4Q531, 22:8) | Enoch, sarcastically called “a wild man” by the “wild men” of the gibborim, proves stronger than them through his “faith” (Moses 6:38) | |

| Wild beasts | Lion is slain by Nebuchadnezzar, proving his power over “wild beasts” | The power of Daniel’s God subjugates the wild beasts in the lions’ den (6:16–23) | “the roar of the wild beasts,” presumably subjugated as part of Enoch’s victory through God’s power (4Q531, 22:8[31]) | “the roar of the lions,” presumably subjugated as part of Enoch’s victory through God’s power (Moses 7:13) |

Convergence of motifs in ancient sources and Moses 6-7.

Despite differences in the details of these stories,[32] Doak argues for the possibility of a deliberate convergence of patterns between the Nebuchadnezzar reliefs, Daniel 4, and the “fusion of the image of the humbling of the giants through dream-visions with the wild man and tree stump motifs in the Book of Giants.”[33] Going further, we add the story of Daniel in the lion’s den and the Book of Moses Enoch account to fill out the table above.

Besides the ironic reversal of the roles of Enoch and his wicked opponent as “wild men” (as discussed in a previous Essay[34]), a similar turning of the tables is now apparent in the subjugation of the wild beasts/lions to the God of the righteous Daniel and Enoch, rather than to their wicked adversaries. The same God who “shut the lions’ mouths”[35] to save Daniel from harm opened the mouth of Enoch to destroy his enemies through the “power of [his] language.”[36]

As demonstrated in the remarkable evidences described in this article, Joseph Smith’s account of Enoch stretches ancient threads beyond Second Temple Judaism and into Mesopotamia.[37] For those who see an authentic historic core in the story of Enoch found in the Book of Moses, such findings are not altogether surprising.

This article was adapted and expanded from Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014, pp. 48–49, 346, 348.

Further Reading

Angel, Joseph L. “The humbling of the arrogant and the ‘wild man’ and ‘tree stump’ traditions in the Book of Giants and Daniel 4.” In Ancient Tales of Giants from Qumran and Turfan: Contexts, Traditions, and Influences, edited by Matthew Goff, Loren T. Stuckenbruck and Enrico Morano. Wissenschlaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 360, ed. Jörg Frey, 61-80. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, 2016, pp. 72–77.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014, pp. 48–49, 346, 348, 386, 388–390, 393–397, 414–415.

Doak, Brian R. “The giant in a thousand years: Tracing narratives of gigantism in the Hebrew Bible and beyond.” In Ancient Tales of Giants from Qumran and Turfan: Contexts, Traditions, and Influences, edited by Matthew Goff, Loren T. Stuckenbruck and Enrico Morano. Wissenschlaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 360, ed. Jörg Frey, 13–32. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, 2016, pp. 24–25.

Draper, Richard D., S. Kent Brown, and Michael D. Rhodes. The Pearl of Great Price: A Verse-by-Verse Commentary. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005, p. 119.

Nibley, Hugh W. “Churches in the wilderness.” In Nibley on the Timely and the Timeless, edited by Truman G. Madsen, 155–212. Salt Lake City, Utah: Bookcraft, 1978, pp. 160–161.

Nibley, Hugh W. Enoch the Prophet. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 2. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986, p. 280.

Nibley, Hugh W. 1986. Teachings of the Pearl of Great Price. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS), Brigham Young University, 2004, p. 282.

Reade, Julian Edgeworth. 2018. “The Assyrian Royal Hunt.” In I am Ashurbanipal: King of the World, King of Assyria (The BP Exhibition at The British Museum), edited by Gareth Brereton. London, England: Thames and Hudson and The British Museum, 2019.

References

Abegg, Martin, Jr., Peter Flint, and Eugene Ulrich, eds. The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible. New York City, NY: Harper, 1999.

Angel, Joseph L. “The humbling of the arrogant and the “wild man” and “tree stump” traditions in the Book of Giants and Daniel 4.” In Ancient Tales of Giants from Qumran and Turfan: Contexts, Traditions, and Influences, edited by Matthew Goff, Loren T. Stuckenbruck and Enrico Morano. Wissenschlaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 360, ed. Jörg Frey, 61-80. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, 2016.

Bradley, Don. The Lost 116 Pages: Reconsructing the Book of Mormon’s Missing Stories. Draper, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2019.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014. www.templethemes.net.

Collins, John J. Daniel. Hermeneia — A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible, ed. Frank Moore Cross. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1993.

Doak, Brian R. “The giant in a thousand years: Tracing narratives of gigantism in the Hebrew Bible and beyond.” In Ancient Tales of Giants from Qumran and Turfan: Contexts, Traditions, and Influences, edited by Matthew Goff, Loren T. Stuckenbruck and Enrico Morano. Wissenschlaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 360, ed. Jörg Frey, 13-32. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, 2016.

George, Andrew, ed. 1999. The Epic of Gilgamesh. London, England: The Penguin Group, 2003.

Goff, Matthew. “The sons of the Watchers in the Book of Watchers and the Qumran Book of Giants.” In Ancient Tales of Giants from Qumran and Turfan: Contexts, Traditions, and Influences, edited by Matthew Goff, Loren T. Stuckenbruck and Enrico Morano. Wissenschlaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 360, ed. Jörg Frey, 115-27. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, 2016.

Grossman, Jonathan. “Who are the sons of God? A new suggestion.” Biblica 99, no. 1 (January 2018): 1-18. https://www.academia.edu/40515229/_Who_are_the_Sons_of_God_A_New_Suggestion_. (accessed February 16, 2020).

Hallo, William W., and K. Lawson Younger, eds. The Context of Scripture. 3 vols. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill Academic Publishers, 1996-2002.

Hartman, Louis F., and Alexander A. Di Lella. 1978. The Book of Daniel. The Anchor Yale Bible, ed. William Foxwell Albright and David Noel Freedman. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005.

Henze, Matthias. “Additions to Daniel: Bel and the dragon.” In Outside the Bible: Ancient Jewish Writings Related to Scripture, edited by Louis H. Feldman, James L. Kugel and Lawrence H. Schiffman. 3 vols. Vol. 2, 135-39. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society, 2013.

Lambert, Wilfred G. Babylonian Wisdom Literature. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1960. Reprint, Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1996. http://books.google.com/books?id=vYuRDcieF2EC&dq. (accessed September 29).

Martinez, Florentino Garcia. “The Book of Giants (4Q531).” In The Dead Sea Scrolls Translated: The Qumran Texts in English, edited by Florentino Garcia Martinez. 2nd ed. Translated by Wilfred G. E. Watson, 262. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1996.

Milik, Józef Tadeusz, and Matthew Black, eds. The Books of Enoch: Aramaic Fragments from Qumran Cave 4. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press, 1976.

Naqvi, Asif. n.d. British Museum: Assyrian Lion Hunt Reliefs and Much More. In Asif Naqvi Photoworks. https://www.aksgar.me/british-museum. (accessed February 15, 2020).

Parry, Donald W., and Emanuel Tov, eds. The Dead Sea Scrolls Reader. 6 vols. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2005.

Pietersma, Albert, and Benjamin G. Wright, eds. A New English Translation of the Septuagint and the Other Greek Translations Traditionally Included Under That Title. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Reade, Julian Edgeworth. 2018. “The Assyrian Royal Hunt.” In I am Ashurbanipal: King of the World, King of Assyria (The BP Exhibition at The British Museum), edited by Gareth Brereton. London, England: Thames and Hudson and The British Museum, 2019.

Stuckenbruck, Loren T. The Book of Giants from Qumran: Texts, Translation, and Commentary. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, 1997.

Tvedtnes, John A., Brian M. Hauglid, and John Gee, eds. Traditions about the Early Life of Abraham. Studies in the Book of Abraham 1, ed. John Gee. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, Brigham Young University, 2001.

Notes for Figures

Figure 1. http://classconnection.s3.amazonaws.com/128/flashcards/2014128/png/ashurbanipal_hunting_lions1349142126836.png (accessed February 15, 2020). The bas-relief is currently housed in The British Museum. Asif Naqvi’s description of the work as displayed at an exhibition of Assyrian Lion Hunt Reliefs at The British Museum is as follows (A. Naqvi, British Museum: Assyrian Lion Hunt):

This is one of the very vivid moments which speaks clearly on its behalf without any narration. The king, on foot, wearing his elegant costume and accessories, grips the lion’s neck firmly with his left hand while the right hand stabs a sword rapidly and deeply into the lion’s belly. The king, rigid-faced, and the lion, roaring in fear and agony, look at each other. The king’s attendant holds a bow and arrows but does not seem to do anything to protect his master; it is not credible that the king exposed himself to mauling from a slightly wounded but still vigorous and aggressive lion in the way that this sculpture, viewed in isolation, implies. The lion is in a very close proximity, almost touching the king with his sharp paws.

For an in-depth discussion of the Assyrian Royal Hunt, with an emphasis on the exploits of Ashurbanipal, see J. E. Reade, Assyrian Royal Hunt.

A similar scene appears on the Assyrian imperial seal (see J. E. Reade, Assyrian Royal Hunt, p. 75 and p. 89 Figure 92). Brian R. Doak has described the connection “between elite military victory against a prestige animal (lion) and the defeat of [a] giant” (B. R. Doak, Giant in a Thousand Years, p. 24.) — which may help explain why “wild man” and “wild beast” appear in the same breath in the Book of Giants.

Figure 2. Published in J. M. Bradshaw, et al., God’s Image 2, Figure G10-7, p. 346. Quote in the caption is from J. E. Reade, Assyrian Royal Hunt, p. 54.

Figure 3. From J. L. Angel, Humbling, p. 74.

Figure 4. From J. L. Angel, Humbling, p. 75.

Endnotes

The close relationship of the two royal activities—killing animals which were dangerous like lions or merely wild, and killing people who were dangerous enemies or merely foreign—is implicit in several inscriptions of Assyrian kings, between the eleventh and ninth centuries.

Reade provides several examples of these activities being closely associated in art and inscriptions. One inscription from Tiglath-pileser I (1115–1076 BCE) (ibid., p. 56):

after giving extensive details of forty-two lands and rulers that the king has conquered, immediately proceeds to describe four extraordinarily strong, wild, virile bulls he has shot in the desert … in just the same way as he has brought enemy booty home; there were also ten elephants killed and four captured, and 120 lions killed on foot and 800 lions killed from his chariot.

Louis Hartman and Alexander Di Lella caution as follows regarding the historical setting of this story (L. F. Hartman et al., Book of Daniel, p. 199):

Whereas the keeping of lions in ancient Mesopotamia is well attested in the inscriptions and stone reliefs of the Assyrian kings, who used to let the lions out of their cage to hunt them down, there is no ancient evidence for the keeping of lions in underground pits, apart from the present story and perhaps its variant [Bel and the Dragon]. Perhaps one might compare, for a later period, the hypogeum of the Roman Colosseum, where animals were kept before being brought up to the arena.

A temporary holding area for lions is also attested in an 1800 BCE letter from a senior official to a king of Mari in Old Babylon (J. E. Reade, Assyrian Royal Hunt, pp. 54–55).

Trackbacks/Pingbacks