This series is cross-posted with the permission of Book of Mormon Central

from their website at Pearl of Great Price Central

Audio Player

Figure 1. Greg K. Olsen: Keeper of the Gate

Knowledge as the Prize in Adam and Eve’s Test of Obedience

The battle begun in the premortal councils and waged again in the Garden of Eden was a test of obedience for Adam and Eve. However, it should be remembered that the actual prize at stake was knowledge—the knowledge required for them to be saved and, ultimately, to be exalted. The Prophet taught that the “principle of knowledge is the principle of salvation,”[1] therefore “anyone that cannot get knowledge to be saved will be damned.”[2]

This raises a question: Since salvation was to come through knowledge, why did Satan encourage—rather than prevent—the eating of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge by Adam and Eve? Surprisingly, the scriptural story makes it evident that their transgression must have been as much an important part of the Devil’s strategy as it was a central feature of the Father’s plan. In this one respect, the programs of God and Satan seem to have had something in common.

However, the difference in intention between God and Satan became apparent when it was time for Adam and Eve to take the next step.[3] In this regard, the scriptures seem to suggest that the Adversary wanted Adam and Eve to eat of the fruit of the Tree of Life directly after they partook of the Tree of Knowledge—a danger that moved God to take immediate preventive action by the placement of the cherubim and the flaming sword.[4] For had Adam and Eve eaten of the fruit of the Tree of Life at that time, “there would have been no death” and no “space granted unto man in which he might repent”—in other words no “probationary state” to prepare for a final judgment and resurrection.[5]

It is easy to see a parallel between Satan’s initial proposal in the spirit world and his later strategy to “frustrate” the plan of salvation through his actions in Eden. Just as his defeated premortal scheme had proposed to provide a limited measure of “salvation” for all by precluding the opportunity for exaltation,[6] so it seems that his unsuccessful scheme in the Garden was intended to impose an inferior form of immortality that would have forestalled the possibility of eternal life.[7] Fortunately, however, because the Devil “knew not the mind of God,” his efforts “to destroy the world”[8] would be in vain: the result of his deceitful manipulations to get Adam and Eve to eat of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge was co-opted[9] by God, and the risk of Adam and Eve’s partaking immediately of the fruit of the Tree of Life was averted by the merciful placement of the cherubim and flaming sword.

The Father did intend—eventually—for Adam and Eve to partake of the Tree of Life, but not until they had learned through mortal experience to distinguish good from evil.[10]

With this understanding as a background, let us examine the story of the Fall in more detail.

Satan’s Strategy for Confusion and Deception

The serpent, represented in scripture as Satan’s alter ego (or perhaps his associate[11]), is described as “subtle.”[12] The Hebrew term behind the word

thus depicts it as shrewd, cunning, and crafty, but not as wise.[13] “Subtle,” in this context, also has to do with the ability to make something appear one way when it is actually another. Thus, it is not in the least out of character later for Satan both to disguise his identity and to distort the true nature of a situation in order to deceive.[14]

At the moment of temptation, Satan deliberately tries to confuse Eve. The Devil—and the scripture reader—know that there are two trees in the midst of the Garden, but only one of them is visible to Eve.[15] Moreover, as Margaret Barker explains:

He made the two trees seem identical: the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil would open her eyes, and she would be like God, knowing both good and evil. Almost the same was true of the Tree of Life, for Wisdom opened the eyes of those who ate her fruit, and as they became wise, they became divine.[16]

Figure 2. Giuliano Bugiardini, 1475-1554: Adam, Eve (detail), ca. 1510

A second theme of confusion stems from Satan’s efforts to mask his identity. The painting shown here portrays the Tempter in the dual guise of a serpent and a woman whose hair and facial features exactly mirror those of Eve. This common form of medieval portrayal was not intended to assert that the woman was devilish, but rather to depict the Devil as trying to allay Eve’s fears, deceptively appealing to her by appearing in a form that resembled her own.[17]

However, the more pertinent aspect of Satan’s deceptive appearance to Eve in the Garden of Eden is the symbolism of the serpent itself. Of great significance here is the fact that the serpent is a frequently used representation of Christ and his life-giving power.[18] Moreover, with specific relevance to the location of his appearance to Eve, evidence suggests that the form of the Seraphim, whose function it was to guard the Divine Throne, was that of a fiery winged serpent.[19] In the context of the temptation of Eve, Richard D. Draper, S. Kent Brown, and Michael D. Rhodes conclude that Satan “has effectively come as the Messiah, offering a promise that only the Messiah can offer, for it is the Messiah who will control the powers of life and death and can promise life, not Satan.”[20]

Not only has the Devil come in guise of the Holy One, he seems to have deliberately appeared, without authorization, at a most sacred place in the Garden of Eden.[21] If it is true, as Ephrem the Syrian believed, that the Tree of Knowledge was a figure for “the veil for the sanctuary,”[22] then Satan has positioned himself, in the extreme of sacrilegious effrontery, as the very “keeper of the gate.”[23] Thus, in the apt words of BYU Professor Catherine Thomas, Eve was induced to take the fruit “from the wrong hand, having listened to the wrong voice.”[24]

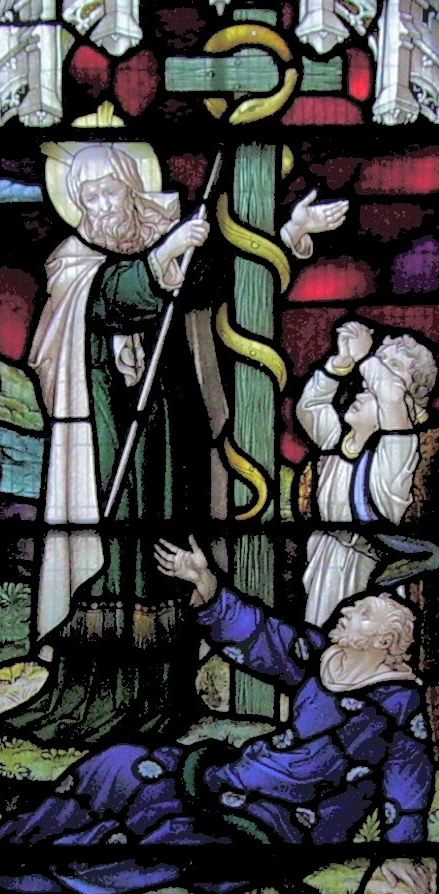

Figure 3. Moses and the Brazen Serpent (detail), ca. 1866

The Forbidden Fruit as a Form of Knowledge

Whether speaking of the heavenly temple or of its earthly models, the theme of access to hidden knowledge is inseparably connected with the passage through the veil. With respect to the heavenly temple, scripture and tradition amply attest of how a knowledge of eternity is available to those who are permitted to enter the heavenly veil.[25] For example, Jewish and Christian accounts speak of a “blueprint” of eternity that is worked out in advance and shown on the inside of the veil to prophetic figures as part of their heavenly ascent.[26] In a similar vein, Islamic tradition speaks of a “white cloth from Paradise” upon which Adam saw the fate of his posterity.[27] Nibley gave the “great round” of the hypocephalus as an example of an attempt to capture the essence of such pictures of eternity among the Egyptians, and showed how similar concepts pervade the literature of other ancient cultures.[28]

With respect to earthly temples, a conventional answer to the question of what kind of knowledge the tree provided is supplied by Psalm 19:7-9 where, in parallel to the description of the forbidden fruit in Genesis 3:6 (“pleasant to the sight, good for food and to be desired to make one wise”), God’s law is described as “making wise the simple, rejoicing the heart and enlightening the eyes.” Gordon Wenham observes:[29]

The law was of course kept in the Holy of Holies: the decalogue inside the ark and the book of the law beside it.[30] Furthermore, Israel knew that touching the ark or even seeing it uncovered brought death, just as eating from the Tree of Knowledge did.[31]

However, given explicit admissions about elements of the First Temple that were later lost, plausibly including things that were once contained in the temple ark, it is reasonable to conjecture that the knowledge in question may have included something more than the Ten Commandments and the Torah as we now know them.[32] Having carefully scrutinized the evidence, Margaret Barker concluded that the lost items were “all associated with the high priesthood.”[33] Also probing the significance of the lost furniture “list of the schoolmen,” Nibley, like Barker, specifically connects the missing “five things” to lost ordinances of the High Priesthood.[34] By piecing together the ancient sources, it can be surmised that the knowledge revealed to those made wise through entering in to the innermost sanctuary of the Temple of Solomon included an understanding of premortal life, the order of creation, and the eternal covenant[35]—and that it “provided a clue to the pattern and future destiny of the universe”[36] that “gave power over creation” when used in righteousness.[37]

Figure 4. William Bell Scott, 1811-1890: The Rending of the Veil, 1867-1868

The rending of the veil at the death of Christ thus symbolizes not only renewed access to the divine presence in heaven but also to the knowledge revealed in earthly temples that makes such access possible.[38]

Consistent with this general idea, Islamic legend insists that the reason Satan was condemned after the Fall was because he had claimed that he would reveal a knowledge of certain things to Adam and Eve.[39] In deceptive counterpoint to God’s authentic teachings to Adam in the Islamic version of the naming episode,[40] Satan is portrayed as recruiting his accomplice, the “fair and prudent” serpent, by promising that he would reveal to it “three mysterious words” which would “preserve [it] from sickness, age, and death.”[41] Having by this means won over the serpent, Satan then directly equates the effect of knowing these secret words with the eating of the forbidden fruit by promising the same protection from death to Eve, if she will but partake.[42]

The fifteenth-century Adamgirk asks: “… if a good secret [or mystery[43]] was in [the evil fruit], why did [God] say not to draw near?”[44] and then answers its own question implicitly. Simply put, the gift by which Adam and Eve would “become divine,”[45] and for which the Tree of Knowledge constituted a part of the approach, was, as yet, “an unattainable thing [t]hat was not in its time.”[46] Though God intended Adam and Eve to advance in knowledge, the condemnation of Satan seems to have come because he had acted without authorization, in the realization that introducing the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge to Adam and Eve under circumstances of disobedience and unpreparedness would bring the consequences of the Fall upon them, putting them in a position of mortal danger.

Note that the knowledge itself was good—indeed it was absolutely necessary for their exaltation. However, some kinds of knowledge are reserved to be revealed by God Himself “in his own time, and in his own way, and according to his own will.”[47] As Joseph Smith taught:

That which is wrong under one circumstance, may be, and often is, right under another. A parent may whip a child, and justly, too, because he stole an apple; whereas if the child had asked for the apple, and the parent had given it, the child would have eaten it with a better appetite; there would have been no stripes; all the pleasure of the apple would have been secured, all the misery of stealing lost. This principle will justly apply to all of God’s dealings with His children. Everything that God gives us is lawful and right; and it is proper that we should enjoy His gifts and blessings whenever and wherever He is disposed to bestow; but if we should seize upon those same blessings and enjoyments without law, without revelation, without commandment, those blessings and enjoyments would prove cursings and vexations.[48]

By way of analogy to the situation of Adam and Eve and its setting in the temple-like layout of the Garden of Eden, recall that service in Israelite temples under conditions of worthiness was intended to sanctify the participants. However, as taught in Levitical laws of purity, doing the same “while defiled by sin, was to court unnecessary danger, perhaps even death.”[49]

Hugh Nibley succinctly sums up the situation: “Satan disobeyed orders when he revealed certain secrets to Adam and Eve, not because they were not known and done in other worlds, but because he was not authorized in that time and place to convey them.”[50] Although Satan had “given the fruit to Adam and Eve, it was not his prerogative to do so—regardless of what had been done in other worlds. (When the time comes for such fruit, it will be given us legitimately.)”[51]

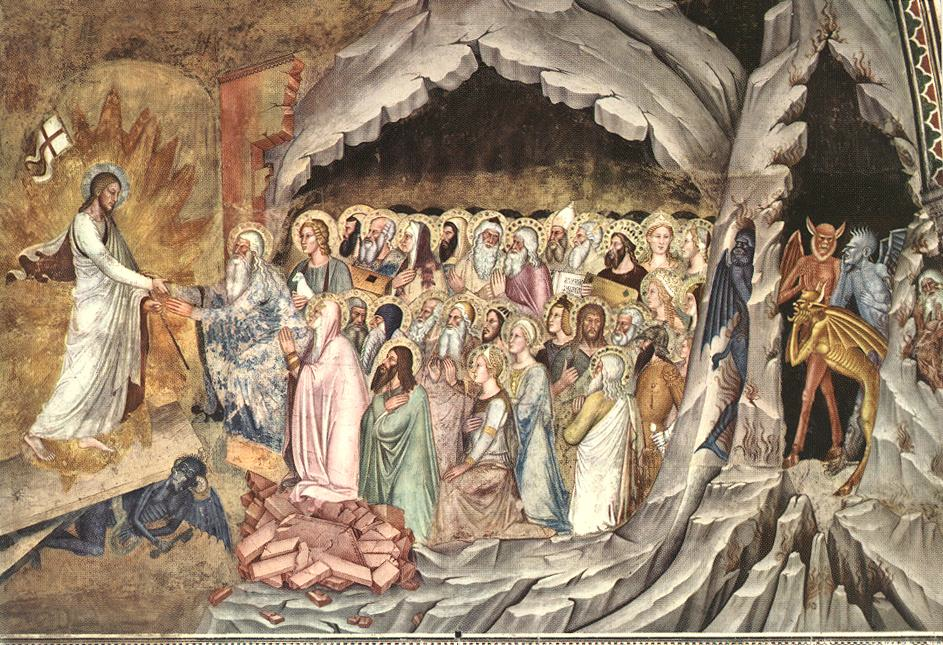

Figure 5. Andrea da Firenze, act. 1343-1377: Descent of Christ to Limbo, 1368

The True “Keeper of the Gate”

This work by Andrea da Firenze illustrates the descent of Jesus Christ, after His death and before His resurrection, into what is called in Roman Catholic tradition “Limbo.”[52] Limbo was described as a place reserved for the just who died before Jesus Christ came to earth (Limbo of the Patriarchs) and also—in the Augustinian tradition at least—for infants who died before they could receive baptism and be freed from “original sin” (Limbo of Infants).[53] Here, in a depiction of an event called “The Harrowing of Hell,”[54] Jesus Christ is shown carrying a Crusader’s flag into the dominion of Death and Hell, whose broken gates are gaping wide.[55] Satan, grasping a useless key, peers out from beneath the feet of the advancing Christ. Adam (recognizable here by his long white hair and beard) and Eve (at his arm) are shown as the first ones to be reclaimed by Christ, followed by Abel (carrying a lamb), and other notables including Abraham, David, and Solomon. As they are brought forth, Adam, Eve, and the other just souls are typically shown in depictions of this scene as being taken by the right hand[56] or pulled by the wrist from the place of death,[57] emphasizing their utter dependence on the sure and steady strength of the Savior for their escape.[58] Nibley paraphrases the teaching of the Pistis Sophia, which emphasizes that “[u]ntil Christ came … no soul had gone through the ordinances in their completeness. It was He who opened the gates and the way of life.”[59]

Figure 6. Ilya Efimovich Repin, 1844-1930: Raising of Jairus’ Daughter, 1871

About this redemptive hour of unalloyed joy, Elder Neal A. Maxwell has written:

God’s is a loving and redeeming hand which we are to acknowledge, for “eye hath not seen, nor ear heard.”[60] Even His children in the telestial kingdom receive “the glory of the telestial, which surpasses all understanding.”[61] He is an exceedingly generous God! … One later day, Jesus’ hand will not give the faithful merely a quick, approving pat on the shoulder. Instead, both Nephi and Mormon tell of the special reunion and welcome at the entrance to His kingdom. There, we are assured, He is “the keeper of the gate … and He employeth no servant there.”[62] Those who reject Him will miss out on a special personal moment, because, as He laments, He has “stood with open arms to receive you.”[63] The unfaithful—along with the faithful—might have been “clasped in the arms of Jesus.”[64] The imagery of the holy temples and holy scriptures thus blend so beautifully, including things pertaining to sacred moments. This is the grand moment toward which we point and from which we should not be deflected. Hence, those who pass through their fiery trials[65] and still acknowledge but trust His hand now will feel the clasp of His arms later![66]

Meanwhile: “One cannot read very far in the scriptures without realizing how much God has concentrated on giving us guidance for the journey between the two gates”[67] of baptism and of celestial glory.

Conclusions

Satan deceived Adam and Eve by offering them fruit from the deceptively described Tree of Knowledge and by enacting a cynically false impersonation of the Savior. Having protected them from the intended consequences of the Devil’s plan of entrapment, God instead offers the first couple and all their posterity the real thing: the fruit of the Tree of Life, the atoning power of the Redeemer to sustain them through their mortal probation, and, ultimately, an everlasting endowment of His power and glory.

This essay is adapted from Jeffrey M. Bradshaw. Temple Themes in the Book of Moses. 2014 update ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Publishing, 2014. English: https://archive.org/details/150904TempleThemesInTheBookOfMoses2014UpdatedEditionSReading ; Spanish: http://www.templethemes.net/books/171219-SPA-TempleThemesInTheBookOfMoses.pdf, pp. 94–105.

Notes on Figures

Figure 1. https://www.gregolsen.com/gallery/keeper-of-the-gate-15×23-limited-edition-paper-1500-sn-framed/ (accessed June 29, 2021).

Figure 2. Photograph IMGP9635, © Stephen T. Whitlock.

Figure 3. St. Mark’s Church, Gillingham, England, Photograph by Mike Young.

Figure 4. Courtesy of Peter Nahum at The Leicester Galleries, http://www.leicestergalleries.com.

Public Domain, http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/83/Descent_of_Christ_to_Limbo_WGA.jpg.

References

al-Kisa’i, Muhammad ibn Abd Allah. ca. 1000-1100. Tales of the Prophets (Qisas al-anbiya). Translated by Wheeler M. Thackston, Jr. Great Books of the Islamic World, ed. Seyyed Hossein Nasr. Chicago, IL: KAZI Publications, 1997.

al-Tha’labi, Abu Ishaq Ahmad Ibn Muhammad Ibn Ibrahim. d. 1035. ‘Ara’is Al-Majalis Fi Qisas Al-Anbiya’ or "Lives of the Prophets". Translated by William M. Brinner. Studies in Arabic Literature, Supplements to the Journal of Arabic Literature, Volume 24, ed. Suzanne Pinckney Stetkevych. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2002.

Alexander, T. Desmond. From Eden to the New Jerusalem: An Introduction to Biblical Theology. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel, 2008.

Anderson, Gary A., and Michael Stone, eds. A Synopsis of the Books of Adam and Eve 2nd ed. Society of Biblical Literature: Early Judaism and its Literature, ed. John C. Reeves. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1999.

Anderson, Gary A. The Genesis of Perfection: Adam and Eve in Jewish and Christian Imagination. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001.

Barker, Margaret. Where shall wisdom be found? In Russian Orthodox Church: Representation to the European Institutions. http://orthodoxeurope.org/page/11/1/7.aspx. (accessed December 24, 2007).

———. The Older Testament: The Survival of Themes from the Ancient Royal Cult in Sectarian Judaism and Early Christianity. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), 1987.

———. The Revelation of Jesus Christ: Which God Gave to Him to Show to His Servants What Must Soon Take Place (Revelation 1.1). Edinburgh, Scotland: T&T Clark, 2000.

———. "The veil as the boundary." In The Great High Priest: The Temple Roots of Christian Liturgy, edited by Margaret Barker, 202-28. London, England: T & T Clark, 2003.

———. Temple Theology. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), 2004.

———. The Hidden Tradition of the Kingdom of God. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), 2007.

Box, G. H. 1918. The Apocalypse of Abraham. Translations of Early Documents, Series 1: Palestinian Jewish Texts (Pre-Rabbinic). London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1919. https://www.marquette.edu/maqom/box.pdf. (accessed July 10, 2020).

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. "The Ezekiel Mural at Dura Europos: A tangible witness of Philo’s Jewish mysteries?" BYU Studies 49, no. 1 (2010): 4-49. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol49/iss1/2/.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and Ronan J. Head. "Mormonism’s Satan and the Tree of Life (Longer version of an invited presentation originally given at the 2009 Conference of the European Mormon Studies Association, Turin, Italy, 30-31 July 2009)." Element: A Journal of Mormon Philosophy and Theology 4, no. 2 (2010): 1-54. http://www.templethemes.net/publications/1%20-%20Bradshaw%20Head%20-%20Mormonisms%20Satan%20and%20the%20Tree%20of%20Life.pdf.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. Creation, Fall, and the Story of Adam and Eve. 2014 Updated ed. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014. https://archive.org/download/140123IGIL12014ReadingS.

Budge, E. A. Wallis, ed. The Book of the Cave of Treasures. London, England: The Religious Tract Society, 1927. Reprint, New York City, NY: Cosimo Classics, 2005.

Bynum, Caroline Walker. The Resurrection of the Body in Western Christianity, 200-1336. Lectures on the History of Religions, American Council of Learned Societies, New Series 15. New York City, NY: Columbia University Press, 1995.

Charlesworth, James H. The Good and Evil Serpent: How a Universal Symbol Became Christianized. The Anchor Bible Reference Library, ed. John J. Collins. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010.

Compton, Todd M. "The handclasp and embrace as tokens of recognition." In By Study and Also by Faith: Essays in Honor of Hugh W. Nibley, edited by John M. Lundquist and Stephen D. Ricks. 2 vols. Vol. 1, 611-42. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1990.

Condie, Spencer J. Your Agency: Handle with Care. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1996.

Draper, Richard D., S. Kent Brown, and Michael D. Rhodes. The Pearl of Great Price: A Verse-by-Verse Commentary. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005.

England, Eugene. "George Laub’s Nauvoo Journal." BYU Studies 18, no. 2 (Winter 1978): 151-78.

Ephrem the Syrian. ca. 350-363. "The Commentary on Genesis." In Hymns on Paradise, edited by Sebastian Brock, 197-227. Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1990.

———. ca. 350-363. Hymns on Paradise. Translated by Sebastian Brock. Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1990.

———. ca. 350-363. "The Hymns on Paradise." In Hymns on Paradise, edited by Sebastian Brock, 77-195. Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1990.

Giorgi, Rosa. Anges et Démons. Translated by Dominique Férault. Paris, France: Éditions Hazan, 2003.

Hafen, Bruce C. The Broken Heart. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1989.

Hamilton, Victor P. The Book of Genesis: Chapters 1-17. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1990.

Harrowing of Hell. In Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harrowing_of_Hell. (accessed December 26, 2007).

Harvey, A. E. The New English Bible Companion to the New Testament. 2nd ed. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

International Theological Commission. "The hope of salvation for infants who die without being baptized." Origins: CNS Documentary Service (Washington, DC: Catholic News Service) 36, no. 45 (26 April 2007): 725-46.

Isenberg, Wesley W. "The Gospel of Philip (II, 3)." In The Nag Hammadi Library, edited by James M. Robinson. 3rd, Completely Revised ed, 139-60. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, 1990.

James, Montague Rhodes, ed. 1924. The Apocryphal New Testament. Oxford, England: The Clarendon Press, 1983.

Joines, Karen Randolph. "Winged serpents in Isaiah’s inaugural vision." Journal of Biblical Literature 86, no. 4 (1967): 410-15.

Koester, Helmut, and Thomas O. Lambdin. "The Gospel of Thomas (II, 2)." In The Nag Hammadi Library in English, edited by James M. Robinson. 3rd, Completely Revised ed, 124-38. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, 1990.

Maxwell, Neal A. Wherefore, Ye Must Press Forward. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1977.

———. The Neal A. Maxwell Quote Book. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1997.

McConkie, Bruce R. The Promised Messiah: The First Coming of Christ. The Messiah Series 1, ed. Bruce R. McConkie. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1978.

Mettinger, Tryggve N. D. The Eden Narrative: A Literary and Religio-historical Study of Genesis 2-3. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2007.

Morray-Jones, Christopher R. A. "Transformational mysticism in the apocalyptic-merkabah tradition." Journal of Jewish Studies 43 (1992): 1-31.

———. "Divine names, celestial sanctuaries, and visionary ascents: Approaching the New Testament from the perspective of Merkava traditions." In The Mystery of God: Early Jewish Mysticism and the New Testament, edited by Christopher Rowland and Christopher R. A. Morray-Jones. Compendia Rerum Iudaicarum ad Novum Testamentum 12, eds. Pieter Willem van der Horst and Peter J. Tomson, 219-498. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2009.

Nibley, Hugh W., and Michael D. Rhodes. One Eternal Round. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 19. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2010.

Nibley, Hugh W. 1967. "Apocryphal writings and the teachings of the Dead Sea Scrolls." In Temple and Cosmos: Beyond This Ignorant Present, edited by Don E. Norton. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 12, 264-335. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992.

———. 1975. The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment. 2nd ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005.

———. 1979. "Gifts." In Approaching Zion, edited by D.E. Norton. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 9, 85-117. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1989.

———. 1981. Abraham in Egypt. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 14. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2000.

———. 1986. "Return to the temple." In Temple and Cosmos: Beyond This Ignorant Present, edited by Don E. Norton. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 12, 42-90. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1992. https://mi.byu.edu/book/temple-and-cosmos/. (accessed August 21, 2020).

———. 1986. Teachings of the Pearl of Great Price. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS), Brigham Young University, 2004.

Nickelsburg, George W. E., ed. 1 Enoch 1: A Commentary on the Book of 1 Enoch, Chapters 1-36; 81-108. Hermeneia: A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2001.

O’Reilly, Jennifer. "The trees of Eden in mediaeval iconography." In A Walk in the Garden: Biblical, Iconographical and Literary Images of Eden, edited by Paul Morris and Deborah Sawyer. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 136, eds. David J. A. Clines and Philip R. Davies, 167-204. Sheffield, England: JSOT Press, 1992.

Pratt, Orson. 1880. "Discourse delivered in the Tabernacle, Salt Lake City, Sunday Afternoon, 18 July 1880." In Journal of Discourses. 26 vols. Vol. 21, 286-96. Liverpool and London, England: Latter-day Saints Book Depot, 1853-1886. Reprint, Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1966.

Ricks, Stephen D. "Dexiosis and Dextrarum Iunctio: The sacred handclasp in the classical and early Christian world." The FARMS Review 18, no. 1 (2006): 431-36.

Savedow, Steve, ed. Sepher Rezial Hemelach: The Book of the Angel Rezial. Boston, MA: WeiserBooks, 2000.

Schmidt, Carl, ed. 1905. Pistis Sophia (Askew Codex). Translated by Violet MacDermot. Nag Hammadi Studies 9, ed. Martin Krause, James M. Robinson and Frederik Wisse. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 1978.

Seaich, John Eugene. Ancient Texts and Mormonism: The Real Answer to Critics of Mormonism. 1st ed. Murray, UT: Sounds of Zion, 1983.

———. Ancient Texts and Mormonism: Discovering the Roots of the Eternal Gospel in Ancient Israel and the Primitive Church. 2nd Revised and Enlarged ed. Salt Lake City, UT: n. p., 1995.

Smith, Joseph F. 1919. Gospel Doctrine. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986.

Smith, Joseph, Jr., Andrew F. Ehat, and Lyndon W. Cook. The Words of Joseph Smith: The Contemporary Accounts of the Nauvoo Discourses of the Prophet Joseph, 1980. https://rsc.byu.edu/book/words-joseph-smith. (accessed August 21, 2020).

Smith, Joseph, Jr. 1902-1932. History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Documentary History). 7 vols. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1978.

———. 1938. Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1969.

Stone, Michael E., ed. 1401-1403. Adamgirk’: The Adam Book of Arak’el of Siwnik’. Translated by Michael E. Stone. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Stordalen, Terje. Echoes of Eden: Genesis 2-3 and the Symbolism of the Eden Garden in Biblical Hebrew Literature. Leuven, Belgium: Peeters, 2000.

Thomas, M. Catherine. "Women, priesthood, and the at-one-ment." In Spiritual Lightening: How the Power of the Gospel Can Enlighten Minds and Lighten Burdens, edited by M. Catherine Thomas, 47-58. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1996.

Weil, G., ed. 1846. The Bible, the Koran, and the Talmud or, Biblical Legends of the Mussulmans, Compiled from Arabic Sources, and Compared with Jewish Traditions, Translated from the German. New York City, NY: Harper and Brothers, 1863. Reprint, Kila, MT: Kessinger Publishing, 2006. http://books.google.com/books?id=_jYMAAAAIAAJ. (accessed September 8).

Wenham, Gordon J. 1986. "Sanctuary symbolism in the Garden of Eden story." In I Studied Inscriptions Before the Flood: Ancient Near Eastern, Literary, and Linguistic Approaches to Genesis 1-11, edited by Richard S. Hess and David Toshio Tsumura. Sources for Biblical and Theological Study 4, 399-404. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1994.

Young, Brigham. 1870. "Discourse delivered in the new Tabernacle, Salt Lake City, 30 October 1870." In Journal of Discourses. 282 vols. Vol. 13, 274-83. Liverpool and London, England: Latter-day Saints Book Depot, 1853-1886. Reprint, Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1966.

Endnotes

Satan, on the other hand, was reported in Laub’s account of the Prophet’s statement to have countered with an absurdly unconditional proposal: “Send me, I can save all, even those who sinned against the Holy Ghost” (see J. Smith, Jr., cited in E. England, Laub, discourse apparently given 7 April 1844, p. 22, spelling and punctuation standardized). Apparently trying to do away with the need for an atonement, Satan instead “sought… to redeem… all in their sins” (O. Pratt, 18 July 1880, p. 288; cf. S. J. Condie, Agency, p. 6, Helaman 5:10-11).

It is at the very least questionable whether or not such a “redemption” really would “save” anyone in any sense of the word worth caring about. Be that as it may, it is certain that without the empowering atonement, none could hope to ever attain the degree of righteousness and virtue required for exaltation—for, as President Brigham Young said, “if you undertake to save all, you must save them in unrighteousness and corruption” (B. Young, 30 October 1870, p. 282).

For example, Moses 4:6 says that: “Satan put it [i.e., the idea to beguile Eve] into the heart of the serpent, (for he had drawn away many after him,).” This JST change directly reinforces the idea that the serpent is not to be identified with Satan himself, but is rather a subsequently recruited accomplice. In addition, Moses 4:5 mentions the serpent simply as a “beast of the field which I, the Lord God, had made.” The phrase in Moses 4:7, “And he [Satan] spake by the mouth of the serpent,” further reinforces this same idea. Such an interpretation, however, should be considered in light of what is presented in the LDS temple endowment.

The Gospel of Philip depicts the rending of the veil not as the abolition of the temple ordinances, as the church fathers fondly supposed, but of the opening of those ordinances to all the righteous of Israel, “in order that we might enter into… the truth of it.” “The priesthood can still go within the veil with the high priest (i.e., the Lord).” We are allowed to see what is behind the veil, and “we enter into it in our weakness, through signs and tokens which the world despises” (see W. W. Isenberg, Philip, 85:1-20, p. 159).

According to Brock, Ephrem’s answer for “why God did not from the very first grant to Adam and Eve the higher state he had intended for them… illustrates the very prominent role which he allocates to human free will” (Ephrem the Syrian, Paradise, p. 59). In his Commentary on Genesis, Ephrem writes (Ephrem the Syrian, Commentary, 2:17, p. 209):

God had created the Tree of Life and hidden it from Adam and Eve, first, so that it should not, with its beauty, stir up conflict with them and so double their struggle, and also because it was inappropriate that they should be observant of the commandment of Him who cannot be seen for the sake of a reward that was there before their eyes. Even though God had given them everything else [in the Garden of Eden] out of Grace, He wished to confer on them, out of Justice, the immortal life which is granted through eating of the Tree of Life. He therefore laid down this commandment. Not that it was a large commandment, commensurate with the superlative reward that was in preparation for them; no, He only withheld from them a single tree, just so that they might be subject to a commandment. But He gave them the whole of Paradise, so that they would not feel any compulsion to transgress the law.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks