This series is cross-posted with the permission of Book of Mormon Central

from their website at Pearl of Great Price Central

Audio Player

“How is it that the heavens weep, and shed forth their tears as the rain upon the mountains?”[1]

Describing the literal and figurative weeping of the heavens at the time of Enoch, Hugh Nibley writes:[2]

One of nature’s ironies is that not enough water usually leads to too much. Enoch’s world was plagued by flood as well as drought; we are regaled by the picture of lowering heavens ceaselessly dumping dismal avalanches of rain and snow upon the earth. The constant weeping of Enoch and all the saints is matched in the powerful imagery of the weeping heavens and the earth veiled in darkness under the blackest of skies: In the book of Enoch the same imagery is applied to the meridian and the fulness of times as well as the Adamic age.

In this Essay, we will survey examples of the weeping of the heavens from the time of Creation through the time of Noah.

The Weeping of the Heavens at the Time of Creation

Providing a plausible echo of the imagery of the weeping of the heavens in Enoch’s account is an ancient Jewish theme that is always associated with the second day of Creation, when the heavenly and earthly waters were separated by the firmament. According to David Lieber:[3]

The Midrash pictures the lower waters weeping at being separated from the upper waters, suggesting that there is something poignant in the creative process when things once united are separated.

So painful was the command of God for the waters to separate that they were seen as having actually rebelled.[4] As Heschel recounts:[5]

On the second day of creation, the Holy and Blessed One said: “Let there be an expanse (raki’a) in the midst of the water, that it may separate water from water. God made the expanse, and it separated the water that was below the expanse from the water which was above the expanse.”[6] God said to the waters: “Divide yourselves into two halves; one half shall go up, and the other half shall go down”; but the waters presumptuously all went upward. Said to them the Holy and Blessed One: “I told you that only half should go upward, and all of you went upward?” Said the waters: “We shall not descend!” Thus did they brazenly confront their Creator. … What did the Holy and Blessed One do? God extended His little finger, and they tore into two parts, and God took half of them down against their will. Thus it is written: “God said, ‘let there be an expanse’”[7] (raki’a)—do not read “expanse” (raki’a) but “tear” (keri’a).”

Heschel makes it clear “that the waters rebelled against their Creator not out of competitiveness or jealousy but rather out of protest against the partition made by the Holy and Blessed One between the upper and lower realms.”[8]

Avivah Zornberg has the lower waters complaining:[9] “We want to be in the presence of the King.” This statement is made meaningful in the understanding that the partition that divided the upper and lower divisions of the waters was an allusion to the veil that separated the Holy of Holies from other precincts in the temple. Because of their separation, the lower waters no longer enjoyed the glory of the direct presence of God.[10]

The Weeping of the Heavens at the Time of Enoch

Jewish tradition records that the weeping of the heavens at the time of Enoch included not only the figurative drenching of the world in rain, but also the literal weeping of God, the angels, and the patriarchs. For example, in 3 Enoch, Enoch is led on a tour of heaven where he sees the righteous who have ascended to heaven pray to the Holy One:[11] “Lord of the Universe, how long will you sit upon your throne, as a mourner sits in the days of his mourning, with your right hand behind you, and not redeem your sons?” Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and the rest of the righteous wonder when God will show his compassion and save his children, with the same “right hand” by which he created the heavens and the earth.

God answers the petitioners, explaining that He cannot save His people “in their sins”[12]: “Since these wicked ones have sinned thus and thus, and have transgressed thus and thus before me, how can I deliver my sons from among the nations of the world, reveal my kingdom in the world before the eyes of the gentiles and deliver my great right hand which has been brought low by them?”[13]

Metatron (Enoch) then calls out for the book of remembrance to be read, in which the wicked deeds of the people were recorded, with every letter of the law having been violated from A to Z.[14] “At once, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob began to weep. … [And] Michael, the Prince of Israel, cried out and lamented in a loud voice, saying: ‘Lord, why do you stand aside?’”[15]

Summing up the scene, Elder Neal A. Maxwell observed:[16] “When Enoch saw the heavens weep, they reflected the same drenching and wrenching feelings of the Father.” Sadly, mankind was heedless and the suffering was needless.

The Weeping of the Heavens at the Time of Noah

Even though the heavens are usually conceived of as being far above the earth, Jewish sages knew them as being very near. In one story, Simeon ben Zoma is recorded as having said:[17]

I was pondering the creation of the universe and I have concluded that there was scarcely a handbreadth’s division between the upper and lower waters. For we read in Scripture, “The spirit of God hovered over the waters.”[18] Now Scripture also says: “Like an eagle who rouses his nestlings, hovering over his young.”[19] Just as an eagle, when it flies over its nest, barely touches the nest, so there is barely a handbreadth’s distance separating the upper and lower waters.”

Given the creation setting of this motif, it is not surprising that the Book of Moses associates the weeping of the heavens with the story of the Flood, which, in essence, recounts the destruction and the re-creation of the earth.[20]

To appreciate the complex symbolism in the stories of the Creation and the Flood with respect to the separation and uniting of the waters, one must see the imagery of the Ark as it would have been seen through ancient eyes.[21] Briefly, in the story of the Ark’s bird-like “hovering” motions upon the waters, we are made to understand that, figuratively speaking, the very sky has fallen. As a consequence, the “habitable and culture-orientated world lying between the heavens above and the underworld below, and separating them”[22] by “a handbreadth’s distance,”[23] has utterly disappeared.[24]

New life, of which the Ark was a portent, cannot come into being without some measure of pain and destruction, as Enoch’s account reminds us when it compares the elements of mortal birth to those involved in spiritual rebirth.[25] Like human birth, the re-breaking of the waters when the earth was created anew involved pain—and the action of tearing:[26] “The tear in the waters was necessary to create space in which life could develop, and the tear of birth is necessary for the baby to begin an independent life.” The weeping of the heavens witnessed by Enoch as a prelude to the Flood, and the rains that attended the Flood itself were inevitable accompaniments to the pain of the birthing of a new telestial earth, separated for a second time from heaven.

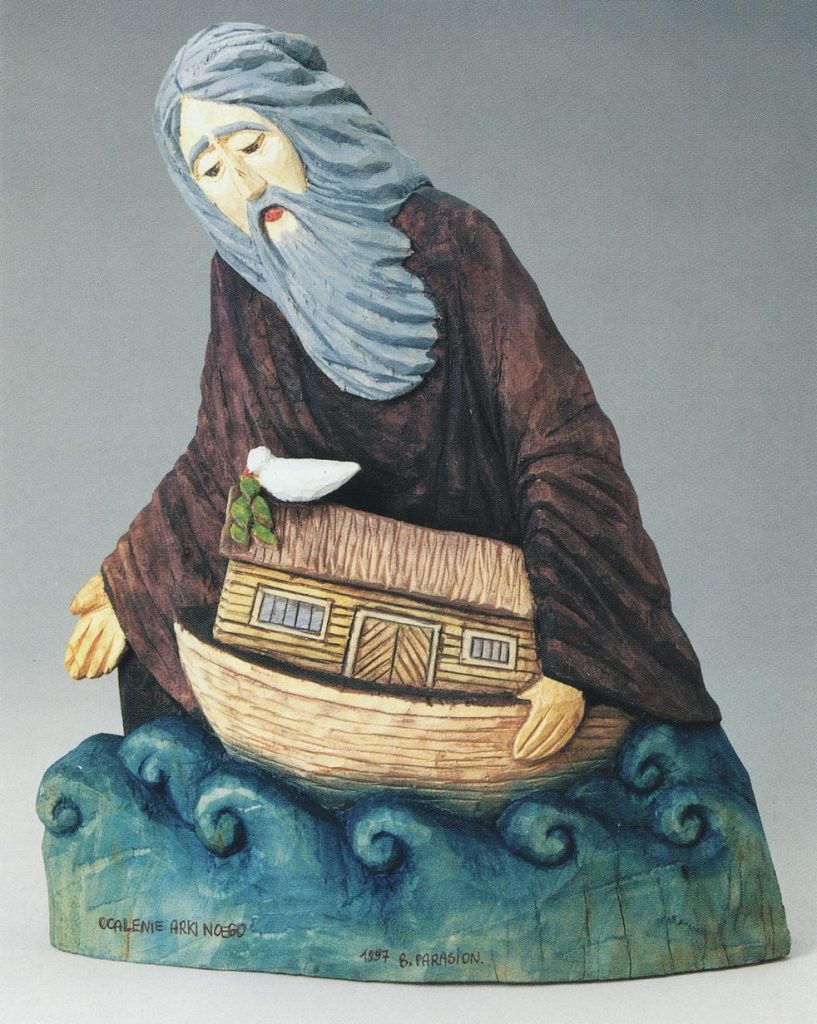

Boleslaw Parasion, 1950–: Noah’s Ark[27]

The sculpture above is drawn from former mission president Walter Whipple’s large collection of Polish folk art. It “depicts a thoughtful God guiding the Ark with his hands.”[28]

Although the Bible does not mention explicitly God’s role during the Flood at the time of Noah, the scene shown in the sculpture is described in 1 Enoch 67:2:[29] “I will put my hand upon [the Ark] and protect it.” George Nickelsburg conjectures that “God’s placing a protective hand on the Ark corresponds either to Genesis 7:16 (“and YHWH shut him in”), or to the covering of the Ark mentioned in Genesis 6:16; 8:13, or both.”[30]

However, we discover a better parallel to 1 Enoch than anything in Genesis in the Grand Vision of Enoch found in Moses 7:43: “Enoch saw that Noah built an ark; and that the Lord smiled upon it, and held it in his own hand.” The language of the Lord smiling upon the Ark is reminiscent of the priestly blessing of Numbers 6:25 (“The Lord make his face shine upon thee”) but the passage finds an even greater resonance in 3 Nephi 19:25 when Jesus visited his disciples and “his countenance did smile upon them, and the light of his countenance did shine upon them.”

In this connection, some ancient interpreters saw in the mention of a tsohar in the Ark an allusion to a shining stone that was said to have hung from its rafters in order to lighten the darkness within.[31] Readers of the Book of Mormon will not miss the similarity to the story of the shining stones divinely provided to the brother of Jared to provide light for their barges.[32]

While the heavens wept for the destruction of the earth, the light of the Lord smiled upon the Ark as a portent of a new Creation. And not only can God hold the Ark “in his own hand,”[33] He has already told Enoch that He can “stretch forth [his] hands and hold all the creations which [he has] made.”[34] In passages resonating with this Book of Moses imagery, Jewish mystical tradition envisions Enoch as protectively holding the cosmos in his hands in a joint effort with God Himself.[35]

This article is adapted and expanded from Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014, pp. 108–110, 148 n. 37d, 149 n. 40a, 259.

Further Reading

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014, pp. 108–110, 148 n. 37d, 149 n. 40a, 259. https://interpreterfoundation.org/books/in-gods-image-and-likeness-2-enoch-noah-and-the-tower-of-babel/.

Draper, Richard D., S. Kent Brown, and Michael D. Rhodes. The Pearl of Great Price: A Verse-by-Verse Commentary. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005, pp. 128–129, 133, 134–137.

Nibley, Hugh W. Enoch the Prophet. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 2. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986, pp. 198–200.

Nibley, Hugh W. 1986. Teachings of the Pearl of Great Price. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS), Brigham Young University, 2004, pp. 284–285.

References

Alexander, Philip S. "3 (Hebrew Apocalypse of) Enoch." In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. 2 vols. Vol. 1, 223-315. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014. https://interpreterfoundation.org/books/in-gods-image-and-likeness-2-enoch-noah-and-the-tower-of-babel/.

Dant, Doris R. "Polish religious folk art: Gospel echoes from a disparate clime." BYU Studies 37, no. 2 (1997-1998): 88-112.

Freedman, H., and Maurice Simon, eds. 1939. Midrash Rabbah 3rd ed. 10 vols. London, England: Soncino Press, 1983.

Gardner, Brant A. Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary of the Book of Mormon. 6 vols. Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007.

Ginzberg, Louis, ed. The Legends of the Jews. 7 vols. Translated by Henrietta Szold and Paul Radin. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1909-1938. Reprint, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Heschel, Abraham Joshua. 1962, 1965, 1995. Heavenly Torah as Refracted Through the Generations. 3 in 1 vols. Translated by Gordon Tucker. New York City, NY: Continuum International, 2007.

Lieber, David L., ed. Etz Hayim: Torah and Commentary. New York City, NY: The Rabbinical Assembly of the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism, produced by The Jewish Publication Society, 2001.

Maxwell, Neal A. Moving in His Majesty and Power. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2004.

Neusner, Jacob, ed. Genesis Rabbah: The Judaic Commentary to the Book of Genesis, A New American Translation. 3 vols. Vol. 1: Parashiyyot One through Thirty-Three on Genesis 1:1 to 8:14. Brown Judaic Studies 104, ed. Jacob Neusner. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1985.

Nibley, Hugh W. Enoch the Prophet. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 2. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986.

———. "The Babylonian Background." In Lehi in the Desert, The World of the Jaredites, There Were Jaredites, edited by John W. Welch, Darrell L. Matthews and Stephen R. Callister. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 5, 350-79. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1988.

———. 1957. An Approach to the Book of Mormon. 3rd ed. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 6. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1988.

———. 1989-1990. Teachings of the Book of Mormon. 4 vols. Provo, UT: FARMS, 2004.

Nickelsburg, George W. E., ed. 1 Enoch 1: A Commentary on the Book of 1 Enoch, Chapters 1-36; 81-108. Hermeneia: A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2001.

Orlov, Andrei A. "Adoil outside the cosmos: God before and after creation in the Enochic tradition." In Histories of the Hidden God: Concealment and Revelation in Western Gnostic, Esoteric, and Mystical Traditions, edited by April D. DeConick and Grant Adamson. Gnostica: Tests and Interpretations, eds. Garry Trompf, Iaian Gardner and Jason BeDuhn, 30-57. Bristol, CT: Acumen, 2013.

Ouaknin, Marc-Alain, and Éric Smilévitch, eds. 1983. Chapitres de Rabbi Éliézer (Pirqé de Rabbi Éliézer): Midrach sur Genèse, Exode, Nombres, Esther. Les Dix Paroles, ed. Charles Mopsik. Lagrasse, France: Éditions Verdier, 1992.

Reeves, John C., and Annette Yoshiko Reed. Sources from Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. 2 vols. Enoch from Antiquity to the Middle Ages 1. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Wolski, Nathan, ed. The Zohar, Pritzker Edition. Vol. 10. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2016.

Wyatt, Nicolas. "The darkness of Genesis 1:2." In The Mythic Mind: Essays on Cosmology and Religion in Ugaritic and Old Testament Literature, edited by Nicholas Wyatt, 92-101. London, England: Equinox, 2005.

Zornberg, Avivah Gottlieb. Genesis: The Beginning of Desire. Philadelphia, PA: Jewish Publication Society, 1995.

Endnotes

God told the angels: On the first day of Creation, I shall make the heavens and stretch them out; so will Israel raise up the Tabernacle as the dwelling place of my Glory (see Exodus 40:17–19). On the second day I shall put a division between the terrestrial waters and the heavenly waters, so will [Moses] hang up a veil in the Tabernacle to divide the Holy Place and the Most Holy (see Exodus 40:20–21).

It is intriguing that Enoch-Metatron’s governance of the world includes not only administrative functions but also the duty of the physical sustenance of the world. Moshe Idel refers to the treatise The Seventy Names of Metatron where the angel and God seize the world in their hands. This motif of the Deity and his vice-regent grasping the universe in their cosmic hands invokes the conceptual developments found in the Shiur Qomah and Hekhalot materials, where Enoch-Metatron possesses a cosmic corporeality comparable to the physicque of the Deity and is depicted as the measurement of the divine Body.