Review of Thomas A. Wayment, trans., The New Testament: A Translation for Latter-day Saints: A Study Bible (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018). $29.99 print. $17.00 digital. 491 pp.

In a sermon delivered in Salt Lake City, Utah on August 27, 1871, Brigham Young issued this charge:

[If] there is a scholar on the earth who professes to be a Christian, and he can translate [the Bible] any better than King James’s translators did it, he is under obligation to do so, or the curse is upon him. If I understood Greek and Hebrew as some may profess to do, and I knew the Bible was not correctly translated, I should feel myself bound by the law of justice to the inhabitants of the earth to translate that which is incorrect and give it just as it was spoken anciently.

Putting a fine point on it, President Young asked rhetorically “Is that proper?” and answer in the affirmative. “Yes, I would be under obligation to do it.”[1]

English-speaking members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have long cherished the King James Bible, which is both the official English Bible of the Church and has informed Latter-day Saint theological vocabulary since the founding of the Church in 1830. Allusions to and citations of KJV passages and language are woven deeply throughout Latter-day Saint scripture and theological vernacular,[2] and Joseph Smith famously undertook a “new translation” or revision of the KJV as part of his larger restoration project.[3] Given that the Latter-day Saint leaders have historically resisted the adoption of modern English translations of the Bible,[4] it would not be unfounded to assume that the KJV enjoys a supremacy over Bibles among English-speaking Latter-day Saints that will not be contested anytime soon.[5]

Nevertheless, it simply cannot be denied that after 400 years of intense biblical scholarship since the publication of the KJV in 1611, to say nothing of 400 years of development of the English language, the time is long overdue for English-speaking Latter-day Saints to seriously re-examine their exclusive loyalty to the KJV.[6] While the KJV unquestionably remains unsurpassed in literary excellence amongst English Bibles–––the veritable crown jewel in the diadem of English prose and poetry–––the plain fact is that sole reliance on the KJV is in many regards a serious impediment to deeper understanding of the biblical text. President Young’s insistence that faithful scholars are obliged “by the law of justice to the inhabitants of the earth to translate that which is incorrect and give it just as it was spoken anciently” must be seriously reckoned with by members of the Church, as there is abundant justification for just such an undertaking.

Thankfully, Latter-day Saints have now been supplied with a landmark publication that meets this demand. Thomas A. Wayment, currently a professor of Classics and previously a professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University who has published extensively on New Testament and early Christianity in both popular and academic venues,[7] has benefited members of the Church with a fresh, precise, engaging, and approachable translation of the New Testament (henceforth the WT for “Wayment Translation”) geared squarely at a mainstream Latter-day Saint audience.

At the outset, Wayment is quick to clarify what his translation is not. “This translation is not an attempt to replace the King James Bible for Latter-day Saint readers, but it is an invitation to engage again the meaning of the text for a new and more diverse English readership” of the New Testament. If Wayment’s translation, then, is not meant to replace the KJV, what precisely does it intend to accomplish? “This translation intentionally engages the possibility that the New Testament can be rendered into modern language in a way that will help a reader more fully understand the teachings of Jesus, his disciples, and his followers” (vii). This is a worthwhile undertaking, since the inspired words of Jesus and his first century apostles are liable to be obscured if modern readers only have access to them through archaic language that is no longer suitable to their modern needs. “When the language of translation becomes too foreign,” Wayment observes, “too distant from the present age, it is time to consider the possibility of another translation” (vii). The fact that a portion of the revisions made by Joseph Smith in his “new translation” of the Bible were updates to the archaic language of the KJV puts Wayment in good company on this point.[8]

Besides providing a fresh translation, Wayment also endeavors to make his edition “a study tool, an aid to inviting readers into the text so that new meaning can be discovered, and new inspiration can be found” (vii). To that end, the WT overhauls the formatting of the text in some ways that his Latter-day Saint readers are perhaps not too familiar with. This includes the use of “quotation marks to designate what was said and by whom,” a “paragraph structure” as opposed to versification, the minimalization of “the intrusion of verse divisions” by “placing verse designations in a smaller superscript font,” the inclusion of headings to demarcate literary pericopes in narrative and thematic, doctrinal, or structural sections in epistles, and the rendering of intertextual quotations into italics with “notes [to] direct the reader to the source of those quotations” (viii–ix). It is apparent that Wayment and his editor(s) at the Religious Studies Center have put great care into making this an aesthetically pleasing and readable edition.

The study notes in the WT “favor intertextuality, especially with the Book of Mormon and the Doctrine and Covenants.” Wayment informs his readers that he included “those references to help the reader see how the New Testament texts are engaged, developed, and interpreted in the Book of Mormon and the Doctrine and Covenants.” References to the JST are also included in the notes, but Wayment is “selective” in how many JST variant readings he includes because “many of the changes that [Joseph Smith] made are inextricably linked to the King James Version.” Important variant readings found in different Greek manuscripts are likewise provided in the notes, as is commentary on disputed passages of “questionable origin” which “offer[s] an opinion regarding the authenticity” of said passages. Latter-day Saints, naturally, should not be scandalized by potential corruptions in the biblical text (see Article of Faith 8), and in any case, it is important to note disputed or variant readings to “show how the text of the New Testament developed over time.” In instances of clearly spurious passages (e.g. 1 John 5:7–8, the interpolation known commonly today as the Johannine Comma), the offending verses have “been removed from the text and placed in the notes” (ix).

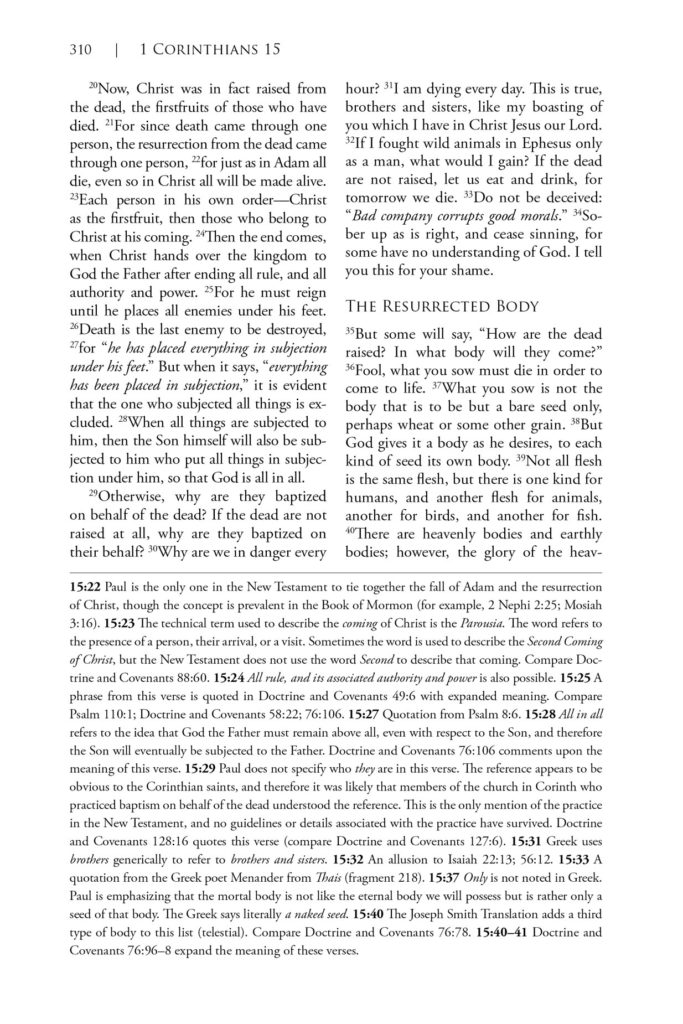

Figure 1. A page from Wayment’s study edition of the New Testament

Figure 2. A page from Wayment’s study edition of the New Testament.

In terms of what kind of the translation Wayment has produced, based on his own prefatory explanation and from a sampling of passages, it appears that the WT is more or less a moderate to formal equivalence of the underlying Greek text somewhere between the New Revised Standard Version and the New International Version. That is to say, Wayment has not “attempted to translate Greek words exactly the same way in each instance, nor the same [grammatical] order in which the words appear in their Greek sentences,” as such would come at the cost of readability. He has, essentially, “chosen to err on the side of context in determining” how to render the Greek (viii).

Take, for instance, the question of how to render the word ἀδελφός (adelphos). A straightforward translation of the word would be “brother,” and, as Wayment notes, there are some passages where “the author appears to have intended ‘men’ exclusively” (e.g. Matthew 2:16; 8:28; 14:21). However, there are many other uses of adelphos in the New Testament that do not require a gender-exclusive rendering of the word. “The original context of the word was not intentionally exclusionary but rather an artifact of first-century common usage and parlance,” notes Wayment. Because the New Testament often uses the word “generically to refer to those who believe alike, regardless of gender,” Wayment opts to translate adelphos inclusively as “brother and sister” in many instances (ix). In my judgment, this is a perfectly reasonable, even laudable, way to stay true to the sense of the Greek (based on context) while adapting the English to be meaningful for a broader–––in this case a gender-non-exclusionary–––audience.

Accordingly, Wayment’s approach is welcome because “the New Testament is written in a variety of different Greek styles,” and so imposing a rigid and uniform rendition of English would obscure the range of refined to simple Greek encountered in the various New Testament books. “A translation that can represent the simple power of the language of Jesus and his followers is truly a gift,” Wayment correctly points out, “and as we are further and further removed from the seventeenth century, we have begun to lose sight of the realization that Jesus spoke like everyday people. Jesus did not speak using archaic English terms and phrases. His speech was quite ordinary, his meaning was quite profound, and his intent was often clear. As language evolves, so too translations need to evolve” (vii). So while Wayment’s translation is not likely to be heard being sung by the King’s Singers in Cambridge (or The Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square in Salt Lake City) during Christmastime, it nevertheless does effectively render the Greek in a readable yet faithful manner.

It is clear that the WT is aimed at a general, non-academic audience. The question might thus naturally arise as to how Wayment navigates historical or textual issues that become apparent from a critical reading of the New Testament. Issues pertaining to authorship, historicity, and textual corruption in the New Testament are handled judiciously by Wayment. True to its self-styling as a “study Bible for Latter-day Saints,” the WT does not shy away from questions or concerns about the authorship and historicity of the New Testament books, but it also does not lose focus on its devotional and pastoral purposes. Nor does it appear to take any overly radical positions at odds with the restored gospel that are propounded by more “liberal” or secular scholars of the New Testament. On the contrary, I found the WT being, at times, fairly “conservative” in how it approaches a number of issues.[9] Take these three examples:

- Concerning the Pericope Adulterae (John 7:53–8:11), Wayment writes, “The earliest manuscripts of the New Testament omit this verse and John 8:1–11. Some manuscripts place the story of the woman caught in adultery at John 7:36, after John 21:25, or after Luke 21:38. The story appears to have strong external support that it originated with Jesus, but it may not have originally been placed here in the Gospel of John or even to have been written by the author of the Fourth Gospel. It is placed in double brackets [in the WT] to indicate that it has questionable textual support, but it is included in the text because it has a reasonable likelihood of describing a historical event from the life of Jesus” (181).

- Concerning the depiction in Luke 22:43–44 of Jesus experiencing hematohidrosis, Wayment writes, “These two verses are greatly disputed, and a number of important ancient manuscripts omit them. Other early and important manuscripts include these verses. Given the current evidence, it is unlikely that the question of their omission or inclusion can be resolved. However, the evidence is strong enough to suggest that they may be original to Luke’s Gospel but were perhaps omitted over doctrinal concerns. Mosiah 3:7 seems to have these verses in mind (compare Doctrine and Covenants 19:16–19)” (156–157).[10]

- Concerning the disputed authorship of Hebrews, Wayment writes, “In one of the earliest Greek manuscripts (Chester Beatty papyrus 46), this epistle is included immediately following Romans, indicating that whoever made that copy of the New Testament felt that Paul was the author of the work because the scribe placed the book alongside the other Pauline epistles. . . . However, there are also significant concerns regarding Paul’s authorship of the letter, and the style of Hebrews and the quality of the Greek writing is so markedly different from Paul’s other letters as to suggest that Paul certainly did not write the letter in the same way and under the same circumstances that he wrote his other letters. . . . Tradition suggests that Paul wrote Hebrews, which is a reasonable assumption; the evidence is fairly conclusive that an early Christian author who was connected to Timothy wrote this epistle with the intent of addressing the topic of Christ for a Jewish Christian audience” (401).[11]

Overall, I found much in Wayment’s new study edition of the New Testament to commend to its intended Latter-day Saint audience. It is precisely the sort of thing that qualified Latter-day Saint biblical scholars can and should be doing for each of the biblical books. The world already benefits from the HarperCollins Study Bible, the Jewish Study Bible, the Catholic Study Bible, and the New Oxford Annotated Bible, to name just a few examples. It’s time for an authoritative Latter-day Saint Study Bible (perhaps a Restoration Study Bible) for both the Old and New Testaments. Wayment has provided a promising glimpse at what a reliable, comprehensive study Bible for Latter-day Saints could look like. If Latter-day Saint scholars collaborated to synthesize the best of biblical scholarship with doctrinal and historical insights from Restoration scripture and the teachings of modern prophets and apostles, I am confident that the publication of just such a study Bible could be accomplished to great benefit for the Saints.

Until that time, every Latter-day Saint wishing to seriously engage the New Testament should pick up a copy of Wayment’s new translation.

Appendix: Parallel Comparison of Select KJV and WT Passages

| Citation | LDS KJV (2013) | Wayment (2018) |

| Matt. 5:14–16 | Ye are the light of the world. A city that is set on a hill cannot be hid. Neither do men light a candle, and put it under a bushel, but on a candlestick; and it giveth light unto all that are in the house. Let your light so shine before men, that they may see your good works, and glorify your Father which is in heaven. | You are the light of the world. A city built on a hill cannot be hid: no one who lights a lamp places it under a basket but on a lampstand, and it gives light to all those in the house. Therefore, let your light shine before people so they may see your good works and give glory to your Father who is in heaven. |

| Matt. 5:48 | Be ye therefore perfect, even as your Father which is in heaven is perfect. | Therefore, you will be perfect, even as your heavenly Father is perfect. |

| Matt. 16:18–19 | And I say unto thee, That thou art Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church; and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it. And I will give unto thee the keys of the kingdom of heaven: and whatsoever thou shalt bind on earth shall be bound in heaven: and whatsoever though shalt loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven. | I say to you that you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of Hades will not overpower it. I will give to you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth, it will be bound in the heavens, and whatever you undo on earth, it will be undone in the heavens. |

| Matt. 28:19–20 | Go ye therefore, and teach all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. Teaching them to observe all things whatsoever I have commanded you; and, lo, I am with you always, even unto the end of the world. Amen. | Go forward, making disciples of all nations and baptizing them in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all things that I have commanded you, and behold, I am with you always, until the end of time. |

| John 3:5 | Jesus answered, Verily, verily, I say unto thee, Except a man be born of water and of the Spirit, he cannot enter into the kingdom of God | Jesus answered, “Truly, truly, I say unto you, unless a person is born of water and Spirit, that person cannot enter the kingdom of God.” |

| John 3:16 | For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life. | For this is how God loved the world: he gave his Only Begotten Son so that all who believe in him will not perish but have eternal life. |

| 1 Cor. 15:20–22 | But now is Christ risen from the dead, and become the firstfruits of them that slept. For since by man came death, by man came also the resurrection of the dead. For as in Adam all die, even so in Christ shall all be made alive. | Now, Christ was in fact raised from the dead, the firstfruits of those who have died. For since death came through one person, the resurrection from the dead came through one person, for just as in Adam all die, even so in Christ all will be made alive. |

| 1 Cor. 15:29 | Else what shall they do which are baptized for the dead, if the dead rise not at all? why are they then baptized for the dead? | Otherwise, why are they baptized on behalf of the dead? If the dead are not raised at all, why are they baptized on their behalf? |

| Eph. 4:11–14 | And he gave some, apostles; and some, prophets; and some, evangelists; and some, pastors and teachers; For the perfecting of the saints, for the work of the ministry, for the edifying of the body of Christ: Till we all come in the unity of the faith, and of the knowledge of the Son of God, unto a perfect man, unto the measure of the stature of the fulness of Christ: That we henceforth be no more children, tossed to and fro, and carried about with every wind of doctrine, by the sleight of man, and cunning craftiness, whereby they lie in wait to deceive. | And he gave some apostles, prophets, evangelists, shepherds, and teachers, to equip the saints for the work of the ministry, for building up the body of Christ, until we all arrive at the unity of faith and the knowledge of the Son of God, at being a mature person at the measure of the stature of the fulness of Christ so that we are no longer infants, tossed back and forth by the waves and carried about by every wind of teaching, by the cunning of people who with craftiness carry out deceitful schemes. |

| 2 Thess. 2:3 | Let no man deceive you by any means: for that day shall not come, except there come a falling away first, and that man of sin be revealed, the son of perdition. | Let no one deceive you by any means, because that day will not come until the apostasy comes first and the man of lawlessness, who is the son of perdition, is revealed. |

| James 1:5 | If any of you lack wisdom, let him ask of God, that giveth to all men liberally, and upbraideth not; and it shall be given him. | If anyone lacks wisdom, let that person ask God, who gives to everyone generously and without reproach, and it will be given to him. |

| 1 Peter 4:6 | For for this cause was the gospel preached also to them that are dead, that they might be judged according to men in the flesh, but live according to God in the spirit. | For this is the reason the gospel was preached also to those who are dead, so that they may be judged in the flesh by human standards, and they may live according to God’s standards. |

| Rev. 22:18–19 | For I testify unto every man that heareth the words of the prophecy of this book, If any man shall add unto these things, God shall add unto him the plagues that are written in this book: And if any man shall take away from the words of the book of this prophecy, God shall take away his part out of the book of life, and out of the holy city, and from the things which are written in this book. | I testify to everyone who hears the words of the prophecy of this book. If anyone adds to them, God will place the plagues that are written in this book upon that person. And if anyone removes anything from the words of the book of this prophecy, God will remove his part from the tree of life and his part in the holy city, which are described in this book. |

For Christmas, I got copies for family members. I think we all agree this is the right study tool to with this year’s study in Sunday School of the New Testament. This translation feels like the KJV served in a more delicious way.

Thanks for the nice review. I would have preferred one-column pages with parallel scriptural references in the margin. The extensive notes are impressive.

This is good. One really wonderful verse in the bible makes no sense to a modern reader reading the King James. “6 Be careful for nothing; but in every thing by prayer and supplication with thanksgiving let your requests be made known unto God.” Philippians 4:6.

This is basically saying, “Don’t worry, but remember God in prayer and be thankful for everything.” It’s a really comforting verse, but no one uses it because what does it mean to “be careful for nothing?”

I’m a little surprised at the support he gives to Pauline authorship of Hebrews. I suspect the average LDS who reads this will not understand it as a tentative judgment, but confirmation of tradition.

Even seeing it brought up in the careful way he does will be a big step for most “average LDS” to take. I wonder how much the authorship of Hebrews should really matter to them? I know a lot of people who will be skittish about even trying any other translation. This is a great opportunity for many to try something new. Wayment shouldn’t scare them off 🙂

Wayment is careful not to ruffle feathers in his book, but on the LDS Perspectives Podcast he makes his own view clear (episode 98, around 35:16): “I don’t think there’s any way Paul wrote this. The person who wrote Hebrews did not write First Corinthians. Full stop.”

It will be interesting to see if this “WT” catches on beyond academic Latter-day Saint circles, especially as 2019 begins, with the church using a new study manual for the New Testament, and all members being expected to study the NT. I postulate the vast majority will stay with the KJV. If this new translation can be of help to some, good.

I am a huge fan and promoter of Elder McConkie’s 3 Vol. Doctrinal New Testament Commentary and plan to keep that at my elbow in both study for and teaching gospel doctrine class.

Further, some readers may not be aware that Elder McConkie gave a talk to CES men called “The Bible: A Sealed Book” (see link below) in which he cautioned them about adopting other translations–this because most all of them were written by Catholic and Protestant (or agnostic) Bible scholars that were biased toward their own theological understanding or that didn’t believe the theology they were translating.

https://www.lds.org/manual/teaching-seminary-preservice-readings-religion-370-471-and-475/the-bible-a-sealed-book?lang=eng

Elder McConkie’s keys to unlocking, or understanding better, the Biblical text are worth evaluation and do allow for a Wayment-type translation, while at the same time cautioning readers about how far such works might have value.

I also note that BYU is publishing a multi-volume New Testament Commentary project, with author names that I have found largely trustworthy and therefore give me hope for their works to be insightful. I do worry that a commentary/text by Julie Smith would be crafted through the lens of feminism, as she is a feminist activist, and that might tend to color and weaken her text. However, these do seem to be potential helpful study resources for those who wish to venture beyond the Come, Follow Me–for Individuals and Families amual, which is obviously prepared for the lowest common denominator throughout the church.

Interpreter’s crowd will want far more, both of milk and meat, and I hope these new publications provide it for them. From what Smoot says in this review, perhaps there is hope.

McConkie’s warning was about “translations of the world.” I’m not sure how much this would apply to a translation by a BYU professor like Thomas Wayment.

On the other hand Brigham Young said, “If [the Bible] be translated incorrectly, and there is a scholar on the earth who professes to be a Christian, and he can translate it any better than King James’s translators did it, he is under obligation to do so, or the curse is upon him.

“If I understood Greek and Hebrew as some may profess to do, and I knew the Bible was not correctly translated, I should feel myself bound by the law of justice to the inhabitants of the earth to translate that which is incorrect and give it just as it was spoken anciently.

“Is that proper? Yes, I would be under obligation.”

–Brigham Young, “Remarks,” New Tabernacle, Salt Lake City, August 27, 1871, in Deseret Evening News, September 2, 1871, 2.

Mark, if you look a little closer, you will notice I said BRM did allow for this WT type of translation; just pointing that out.