One of my favorite Christmas stories comes from Provence, in the south of France. Two hundred years ago, during the French Revolution, the new government prevented the churches from displaying their traditional life-size nativity scenes. As a result, many people began to display small nativity scenes in their own homes. Besides the traditional shepherds and wise men, the nativity figurines included all the villagers of Bethlehem, who are dressed, not in the robes of Bible times, but rather in the traditional clothing of the trades of the French countryside: the musician, the miller, the fisherman, the knife sharpener, and the rich farmer. Each one was portrayed on his way to the stable, bringing his own special gift to the Christ child. This nighttime procession of the villagers to see the Holy Family is the scene pictured in the French Christmas carol “Bring a Torch, Jeannette, Isabella!”[1]

The version of the story I will share today is narrated by an angel named Boufaréo, who speaks with an unmistakable accent from the south of France, where they pronounce their words in a musical way, often with a twang at the end. I will not attempt to mimic the accent, but here is what Boufaréo the angel said about that night:

I’m going to tell you how it all happened, because, after all, from where I was, it was me who had the best view of things. It was the night of December 24, and the wild west wind was blowing and all the people of Bethlehem went to bed early. And they pulled the covers over their heads so they didn’t have to listen to the wind howl. The west wind, which was a friend of the good Lord, had chased the clouds for thousands of miles, so that the sky would be all clean and all shining with stars for the birth of the little one. It was not a bad thought, but it brought the temperature right down. I only had my wings to cover me, and thought I was going to freeze to death. I hunkered down the best I could.

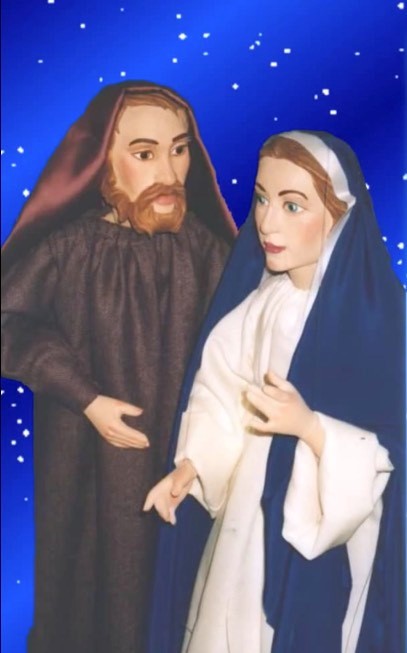

Finally, I saw them, the poor wretches. It was painful to watch. Saint Joseph walked in front, his beard shaken by the wind like a streamer. He tried to shield the holy Mother with his large shoulders. From time to time, he looked back and said:

“How are you doing, my beautiful one?”

“I can’t go on,” Mary replied.

“Keep it up just a little longer. Look, I see a cottage there, close by.”

“No one wants us,” said Mary despairingly.

“Well, maybe not the rich people, but, here, these are the poor. They will surely make a little place for us.”

Mary stumbled and reached out to Joseph, “Give me your arm.”

“Here, hold tight…” he said.

“Oh, how it pains! Aïe!” Mary cried.

“ Oh, aïe, aïe, aïe, aïe, aïe, aïe,” said Joseph, “what misery, oh, we are really in a fix. No money, no house, and a wife who is going to deliver in the middle of the night! And in such awful weather! Don’t be afraid … Wait, I’ll carry you.”

“Please forgive me for being so much trouble, Joseph,” said Mary.

“I’m sure it will all work out,” he replied. “But all the same, the good Lord, He is asking too much. When I agreed to marry you, I should have given Him my terms and conditions.”

“Do you regret it?” Mary asked, gently.

“No, but listen well, my beauty,” said Joseph. “Who am I? Me, a poor nobody. And the good Lord gave me the right to hold you by the hand, to carry you in my arms, you, the mother of His Little One. And you think I might regret it? Oh, but such happiness, it’s something I don’t deserve. If only the good Lord would only help us out a little. Otherwise, we’re headed for disaster! And people will say that it was my fault. Wait here, don’t move, we’re here. Knock, knock, knock. Anyone here? Oh, the poor people are sleeping. I hate to wake them up, but there is no choice. Knock, knock, knock.”

As we all know, Joseph and Mary’s search for lodging ended up in a strawy stable where the baby was cradled in a manger. Eventually each of the villagers in the story was led to the place where Jesus was laid. And as they went along, each of the villagers was touched by their own miracle on that first Christmas night.[2] The lazy Miller, who escaped his great sadness through constant sleep, unexpectedly wakes up with a sudden urge to grind wheat. As if responding to his unspoken intention, the blades of his windmill begin turning, though there was not the slightest breeze to move them. The Thief steals a turkey and is strangely filled with regret. The Constable, who had been trying to catch the Thief for years, just as strangely loses any desire to arrest him. The Fish Woman finds that her rotten fish are now so fresh that they seem almost alive; and her husband Pistachié, a luckless hunter, succeeds in shooting a rabbit for the first time ever, and brings it as a gift to the newborn Child.

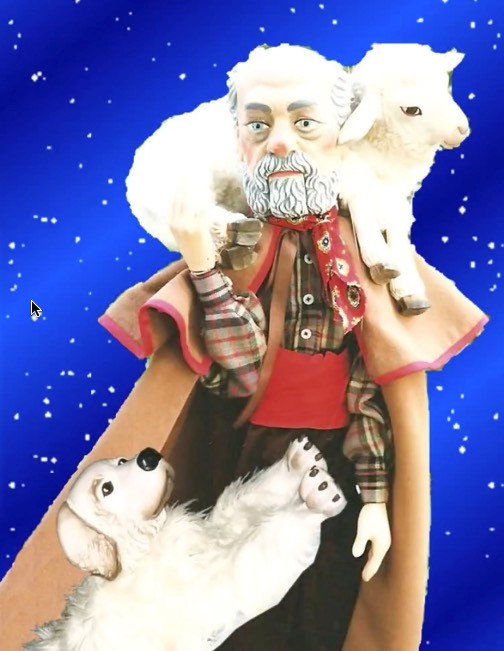

Finally, the old Shepherd, whose only companion, a sheep dog, has died in the night, cries out with joy when his cherished friend suddenly whimpers and returns to life. Thinking the dog might be useful as a guard for the stable, he presents it to the holy Mother. Refusing his offer, Mary says: “Shepherd, my son will someday be a shepherd like you. He will be a shepherd of men, and men don’t need a dog to guard them. They need love.” Mary’s words penetrate the heart of the shepherd and, according to the story, he later became one of the Lord’s apostles.

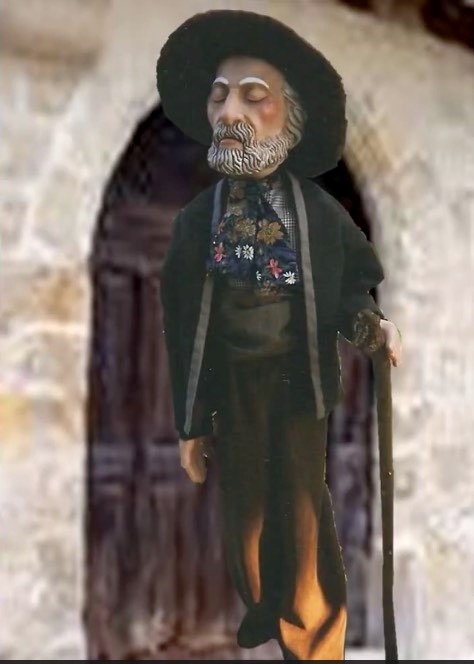

Arriving at the stable, the Blind Man falls to his knees and praises the Lord. Surprised, Mary exclaims: “You thank God, you who have never seen the heavens or the stars? You who are shut up in the darkest of prisons?” Mary begins a prayer to heal his sight, but the Blind Man interrupts: “Oh, no, no, good Mother, no, it’s not worth the trouble. Don’t bother Him. I know that the world is beautiful, because it is He who made it, and I’m certain that the heavens are even more beautiful because it is there that He dwells. No, ask Him only that He does not make me wait a long time; that I shall open my eyes on the day of my death; that I shall see when it will truly be worthwhile to see.”

And then the group of villagers breaks into song.

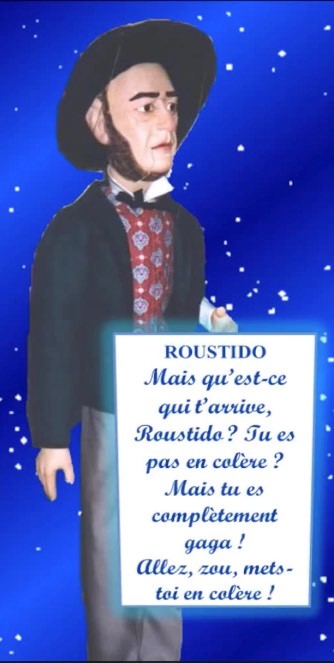

While everyone is singing, another figure enters the stable. It is the heartless miser Roustido. He was the only rich man in Bethlehem, and the more money he got, the more hard-hearted he became. It was he who slammed the door of the inn on Joseph and Mary, calling them beggars and good-for-nothings. The angel explains that Roustido’s name was left out of the Gospels because Jesus’ disciples didn’t want to make him feel bad.

Roustido stays quietly in his corner and, little by little, a feeling of gentleness, of kindness, of goodness comes over him. He fights this wonderful feeling, repeating over and over to himself: “What’s happening to you, Roustido? Why aren’t you angry? You’re completely out of your mind! Come on, get angry, will you!” But instead of rising to shout at the villagers, he continues to stay very still — and he feels better and better as each moment passes.

Then, at last, Roustido gets up. He kneels down before the Holy Family and, passionately smiting his breast, exclaims: “Baby Jesus, I’m a vicious man. When your father and mother came knocking at my door, I left them in the street. I can never forgive myself. I’m a criminal. I am going to prepare a lovely covered carriage for you, with a gentle horse. And I’m going to drive you to my house and put you in the most beautiful and well-heated bedroom. In my bedroom, I mean. And you will stay as long as you like — until the end of your days, if you wish. And your worries will be over.”[3]

Joseph, enticed by the offer, replies: “Ah, you are very kind. What do you say, Mary?” But Mary says: “My Son and I, we thank you, but we cannot accept your offer. We must stay here in the stable to fulfill the will of God.”

And then, at that moment, each of the villagers poses as if for a photograph, but it is not a photograph. Each of the clay figurines of the nativity scene takes its position, then never moves again.[4] They will remain in perfect stillness until the end of the world: Mary and Joseph looking at the sleeping baby Jesus with their heads leaning on their shoulders and their hands folded; the Dreamer, his arms in the air; the Blind Man, leaning on his cane; the hunter Pistachié, leaning on his rifle; the Fish Woman, a basket of fish on each side of her big hips; the Shepherd, with a lamb lying motionless around his neck and his dog sleeping between his legs; the Thief, with his hand resting on the shoulder of the Constable in a friendly way; the miser Roustido, with a smile on his face for the first time in his life; and the ox and the ass who have fallen asleep, overcome with joy.

Why do I love this simple story? Because it conveys the most vital message that each of us can share with those we love during the Christmas season:

- that Christ has come to change men’s hearts;

- that a changed heart means a joy-filled life here and hereafter; and

- that the joy-filled lives of faithful Christians are as millions of lighted candles that can brighten and bring hope to all those who now sit in darkness.

If there is hope for the heartless Roustido, there is hope for you and me. The hope born of deep and permanent change comes not through mere self-discipline or the exercise of will power but through faith and repentance in the only One who can fully refashion human nature in His image. Though we may think it impossible that years of the accumulated bitterness of resentment could all at once be healed by the balm of the pure love of Christ, though we might otherwise despair in the face of repeated failures to overcome weaknesses and addictions, though we may face mountains of troubles of all kinds on every side, I bear my testimony of the great hope we have in our Savior, and in the power of His Atonement.

Adapted from a talk given at the Atmore Branch, Mobile Alabama Stake, 14 December 2014. For a video version of “La pastorale des santons de Provence” accompanied by Yvan Audouard’s French text and including the images of the “santons” used in this article, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gLAh0RmGHA8. For a complete English translation of Audouard’s version of the story, see http://www.templethemes.net/publications.php.

References

Audouard, Yvan. La Pastorale des santons de Provence. Paris, France: Le pré aux clers, 1986.

Barker, Margaret. Christmas: The Original Story. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 2008.

———. "The Infancy Gospel of James and translation of the text." In Christmas: The Original Story, edited by Margaret Barker, 128-61. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 2008.

A Catalan Christmas Carol. In Catholic Inspiration: A Pilgrim’s Collection of Spiritual Matters. http://www.acatholicinspiration.com/2012/01/03/a-catalan-christmas-carol/. (accessed November 22, 2014).

El Noi de la Mare (The Child of the Mother). In Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/El_Noi_de_la_Mare. (accessed November 22, 2014).

Eyring, Henry B. 2010. The gift of a Savior. In 2010 First Presidency Christmas Devotional, 5 December 2010. http://www.lds.org/broadcasts/article/christmas-devotional/2010/12/the-gift-of-a-savior?lang=eng. (accessed November 21, 2014).

Keyte, Hugh, and Andrew Parrott. The New Oxford Book of Carols. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Le jongleur de Notre Dame. In Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Le_Jongleur_de_Notre_Dame. (accessed November 21, 2014).

The Little Drummer Boy. In Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Little_Drummer_Boy. (accessed November 21, 2014).

Monson, Thomas S. 2010. A bright shining star. In 2010 First Presidency Christmas Devotional, 5 December 2010. http://lds.org/broadcasts/article/christmas-devotional/2010/12/a-bright-shining-star?lang=eng. (accessed December 16, 2010).

The Son of Mary (El Noi de la Mare). In ChoralWiki. http://www2.cpdl.org/wiki/index.php/The_Son_of_Mary_(El_Noi_de_la_Mare)_(Traditional). (accessed November 22, 2014).

What Shall We Give? Mormon Tabernacle Choir and Orchestra at Temple Square. In MusixMatch. http://www.musixmatch.com/lyrics/Mormon-Tabernacle-Choir-Orchestra-at-Temple-Square-2/What-Shall-We-Give. (accessed November 22, 2014).

Endnotes

Short Version

1. Què li darem an el Noi de la Mare?

Què li darem que li sàpiga bo?

Li darem panses amb unes balances,

Li darem figues amb un paneró.2. Què li darem al Fillet de Maria?

Què li darem al formós Infantó?

Panses i figues i nous i olives,

Panses i figues i mel i mató.3. Tam-pa-tam-tam que les figues són verdes,

Tam-pa-tam-tam que ja maduraran.

Si no maduren el dia de Pasqua,

maduraran en el dia del Ram.

Long Version

1. Què li darem, an el Noi de la Mare?

Què li darem que li sàpiga bo?

Panses i figues i nous i olives,

panses i figues i mel i mató.2. Què li darem, al fillet de Maria?

què li darem a l’hermós Jesuset?

Jo li voldria donar una cota

que l’abrigués ara que fa tant fred.3. Una cançó jo també cantaria,

una cançó ben bonica d’amor,

i que n’és treta d’una donzelleta

que n’és la Verge Mare del Senyor.4. En eixint de ses virginals entranyes

apar que tot se rebenti de plors,

i la mareta, per a consolar-lo,

ella li canta la dolça cançó.5. No ploris, no, manyaguet de la Mare,

no ploris, no, ai, alè del meu cor!

Cançó és aquesta que el Noi de la Mare,

cançó és aquesta que l’alegra molt.6. Àngels del cel són els que l’en bressolen,

àngels del cel que li fan venir son,

mentre li canten cançons d’alegria,

cants de la glòria que no són del món.7. Què li darem, al fillet de Maria?

què li darem a l’hermós Jesuset?

Li darem panses amb unes balances,

li darem figues amb un paneret:8. Tam, pa, tam, tam, que les figues són verdes,

tam, pa, tam, tam, que ja maduraran;

si no maduren el dia de Pasqua,

maduraran en el dia del Ram.

English Translation 1

1. What shall we give to the child of the Mother?

What shall we give that to him will taste good?

Hazel nuts, honeycomb, figs and ripe olives,

Honey and curds we will bring for his food.2. What shall we give to the sweet son of Mary?

What shall we give to the beautiful child?

Figs in a basket and scales for to weigh them,

Sweet corn and figs we will bring to the child.3. Tan-ta-ta-tan-ta, the figs are not ripened,

Tan-ta-ta-tan-ta, the figs are still green,

They will be ripe by the day of the palm leaves,

Ripe when the bright sun at Easter is seen.

English Translation 2

1. What shall we give to the Son of the Virgin?

What can we give that the Babe will enjoy?

First, we shall give Him a tray full of raisins,

Then we shall offer sweet figs to the Boy.2. What shall we give the Beloved of Mary?

What can we give to her beautiful Child?

Raisins and olives and nutmeats and honey,

Candy and figs and some cheese that is mild.3. What shall we do if the figs are not ripened?

What shall we do if the figs are still green?

We shall not fret; if they’re not ripe for Easter,

On a Palm Sunday, ripe figs will be seen.

The carol has received a beautiful choral arrangement by Mack Wilberg, accompanied by David Warner’s English text that that simplifies the symbolism (What Shall We Give?):

What shall we give to the babe in the manger?

What shall we offer the child in the stall?

Incense and spices and gold we’ve a-plenty-

Are these the gifts for the king of us all?Tan ta tan tan ta ta tan ta ta tan ta

Ta ta tan tan ta ta tan ta ta taWhat shall we give to the boy in the temple,

What shall we offer the man by the sea?

Palms at his feet and hosannas uprising;

Are these for him who will carry the tree?Tan ta tan tan ta ta tan ta ta tan ta

Tan ta tan tan ta ta tan ta ta taWhat shall we give to the lamb who was offered,

Rising the third day and shedding his love?

Tears for his mercy we’ll weep at the manger,

Bathing the infant come down from above.

As I, Joseph, was walking, I did not walk. I looked up into the air in amazement. I looked up into the air in amazement. I looked up to the highest spot in the heavens, and saw it was still, and the birds of the air were not moving. When I looked to the earth I saw a dish set there, and workmen reclining with their hands in the dish. The ones that had been chewing were not chewing, the ones that were taking food [to their mouths] stopped moving. All their faces were looking upwards. There were some sheep being driven, and they stood still. The shepherd about to strike them with his staff remained with his hand in the air. There were kids about to drink from the stream, and they did not drink. And then, suddenly, everything began to move again. (M. Barker, Infancy Gospel of James, 18, p. 158)

Margaret Barker conjectures that this event, along with other details of the story, might have to do with “the mystery of the Holy of Holies, and the writer of the Protoevangelium matching the historical incidents in the nativity story to the symbolism of the ancient temple and the birth of the divine son” (Little Drummer, p. 136). Thus, we might see the temporary interruption of the stream of events as a symbol of the timeless, eternally unchanging state of the Holy of Holies, where God dwells.