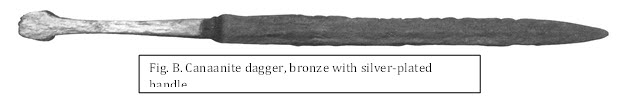

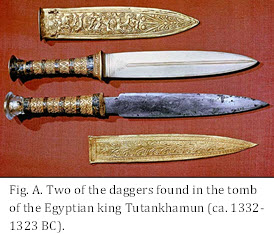

Finding Laban drunk in the streets of Jerusalem, Nephi “beheld his sword, and [he] I drew it forth from the sheath thereof; and the hilt thereof was of pure gold, and the workmanship thereof was exceedingly fine, and . . . the blade thereof was of the most precious steel” (1 Nephi 4:9). ((The golden hilt of Laban’s sword has led a number of people to suggest that this was a special sword, a symbol of office.)) This description is so precise that one is tempted to look for similar weapons from the ancient world in which Laban lived. Comparisons have been made with a long dagger found in the tomb of the fourteenth-century BC Egyptian king Tutankhamun, with its iron blade and hilt of gold, uncovered in 1922 by British archaeologist Howard Carter (see Fig. A). ((Note also the discovery of a Canaanite dagger with a silver-plated handle (Fig. B).)) This comparison is valid insofar as the workmanship is concerned, for Laban’s sword had a steel blade and a gold hilt. But the Egyptian weapon would not have been long enough for Nephi to strike off Laban’s head (1 Nephi 4:18). ((See the discussion in William J. Adams, Jr., “Nephi’s Jerusalem and Laban’s Sword,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 2/2 (1993), 194-95, reprinted in Pressing Forward With the Book of Mormon, eds. John W. Welch and Melvin J. Thorne (Provo: FARMS, 1999), 11-13.))

Gold-hilted swords have been known from both Europe and Asia, but were they known in the region of ancient Israel, where Nephi and Laban lived? The answer is yes. Such weapons are known from the Near East and other places in the eastern Mediterranean, from both ancient texts and archaeological finds. Weapons made of precious metals are mentioned in tablets found in 1975, during excavations of the ancient northwest Syrian city of Ebla (2600–2500 BC), where we read of gold daggers, a silver‑bladed dagger, and silver bows (TM.75.G.1599 obverse III.2–4, VI.3–7, VII.1–3; TM.75.G.2070 obverse VIII.17). ((English translations of the tablets were published in Giovanni Pettinato, The Archives of Ebla: An Empire Inscribed in Clay (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co., 1981). The modern Arabic name of the site is Tell Mardikh.))

Ancient swords that share some features with Laban’s weapon are mentioned in the Iliad, the Greek epic of the Trojan war. ((John A. Tvedtnes, “The Iliad and the Book of Mormon,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 4/2 (Spring 1996): 147-149, reprinted in, Pressing Forward With the Book of Mormon,)) Though its author, Homer, probably lived about 800 BC, the date of the war itself is generally acknowledged to be around 1200 B.C. Consequently, Homer’s description of weapons and battle tactics can be said to be authentic for at least 800 BC and perhaps earlier.

King Menelaus, who led the Greek army against the Trojans, wielded a silver‑studded sword (Iliad 2.45; 3.361; 13.610; 14.405; 23.807–8) or a gold‑studded sword (Iliad 11.29–30), and Hector, leader of the Trojan army, is said to have given Ajax a silver‑studded sword with a sheath (Iliad 7.303–4). Achilles’ sword was bronze with silver studs (Iliad 16.135–36) and had a silver hilt (Iliad 1.219–20). The god Apollo, who participated in the war, is said to have fought with a golden sword (Iliad 5.509).

We can draw a further comparison of Laban’s swords with those mentioned in one of the Dead Sea Scrolls. ((John A. Tvedtnes, “The Workmanship Thereof Was Exceedingly Fine,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 6/1 (1997), 73-75.)) War Scroll (1QM) 5.11-14 describes the swords to be used by the Israelites during the final battle between the forces of good and evil:

The swords shall be of purified iron, refined in a crucible and whitened like a mirror, work of a skilful craftsman; and it will have shapes of an ear of wheat, of pure gold, encrusted in it on both sides. And it will have two straight channels right to the tip, two on each side. Length of the sword: one cubit and a half [about 27 inches]. And its width: four fingers [about 2 inches]. The scabbard will be four thumbs; it will have four palms up to the scabbard and diagonally, the scabbard from one part to the other (will be) five palms. The hilt of the sword will be of select horn, craftwork, with a pattern in many colours: gold, silver and precious stones. ((Florentino García Martínez, The Dead Sea Scrolls Translated (2nd ed., Leiden: Brill, 1996), 99.))

The fact that this text and that of the Book of Mormon mention the gold hilt and the sheath or scabbard of the sword is relatively insignificant. More important is the composition of the hilt and the blade. Laban’s sword blade is made of “the most precious steel,” while the future swords of the Israelite army are to have blades “of purified iron . . . whitened like a mirror.” Nephi describes the hilt of Laban’s sword as being made “of pure gold.” The future Israelite swords will have a hilt “of select horn . . . with a pattern in many colours: gold, silver and precious stones,” though designs in “pure gold” are also mentioned. Both descriptions refer to the “workmanship” or “craftwork” of the swords, saying it was “exceedingly fine” or “of a skilful craftsman.” The War Scroll is particularly detailed when it describes the sword’s ornamentation and size. The idealized Israelite sword described in the War Scroll may reflect the concept of precious swords carried by earlier Israelite leaders such as Laban and perhaps even the kings.

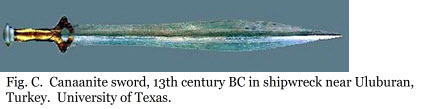

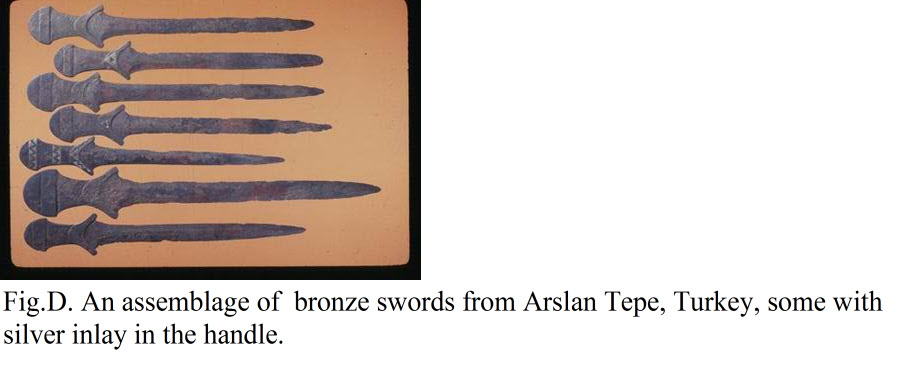

The oldest known swords, forged around 3300-3000 BC, were found at Arslan Tepe in the Taurus mountains of southeastern Anatolia in Turkey. ((A. Palmieri, “Excavations at Arslantepe (Malatya),” Anatolian Studies 31 (1981): 101-119, 1981)) Nine swords, ranging in length from 45 to 60 centimeters [18-24 inches], were found in a palace complex and were made from an arsenic-copper alloy. Three of them were beautifully inlaid with silver (Fig. C). Another sword was found in a royal tomb built just after the destruction of the palace.

A similar cache of weapons is said to have been found in the royal treasure at the site of Dorak in northwestern Anatolia, near the Sea of Marmara. Dating from about 2500 B.C., the cache included a number of swords, of which we have only rubbings prepared by British archaeologist James Melaart, who said he was shown the originals by a Turkish woman who possessed them. Of the bronze swords, one has an ivory hilt with a design formed by red fillings, another a gold hilt decorated with carnelian studs, a third a stained ivory handle covered with gold and a pommel of rock-crystal, a fourth a lion-head pommel of rock-crystal with eyes of lapis lazuli, and a fourth a gold hilt decorated with dolphins and a lapis lazuli pommel. An iron sword from the cache has an obsidian pommel and a hilt studded with gold and amber. Two of the swords have silver blades. One of these has a gold central spine on the blade and a lion-head pommel of pale blue stone with nephrite rivets, while the other has boat engravings on the blade and a silver hilt decorated with gold dolphins.

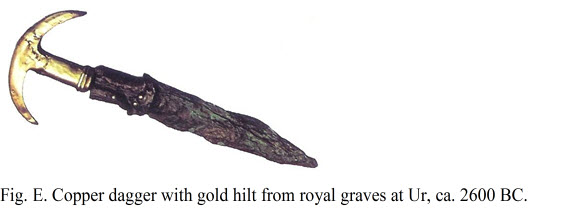

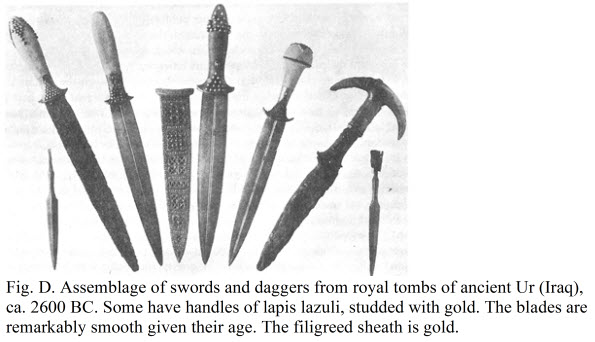

Two gold swords from the same time period as the Dorak finds were uncovered during excavations at the the Royal Cemetery in Ur, a city of southern Mesopotamia (Iraq). One has a blade and lower portion of the hilt made of gold, while the upper portion of the hilt and pommel are comprised of a carved white stone with gold bead inlay for decoration. The other has a blade of gold, while the hilt has gold bead inlay. Of particular interest is that this sword was found with its sheath intact. The sheath is of gold-decorated open-work and has two vertical slits on the back to allow it to be attached to a belt. (Figs. D-F)

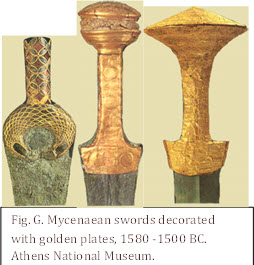

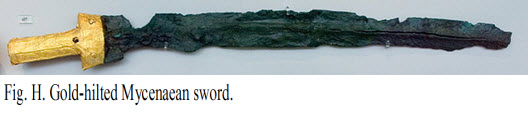

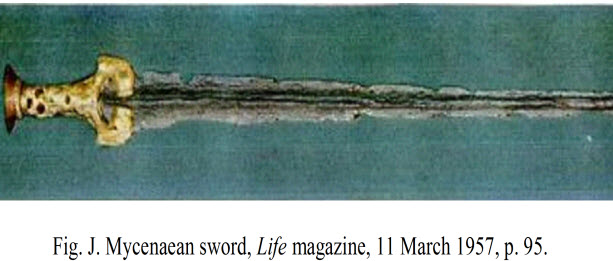

From the region of the Aegean Sea, which separates Greece from Turkey, we have many finds from the Minoan civilization (2700 to 1450 BC) centered in Crete and the Mycenaean civilization (1600–1100 BC), most famous for the Trojan War between various Greek city-states and the city of Troy. Several gold-hilted swords and daggers have been uncovered in this region (Figs. G-J).

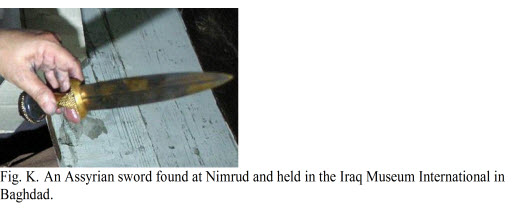

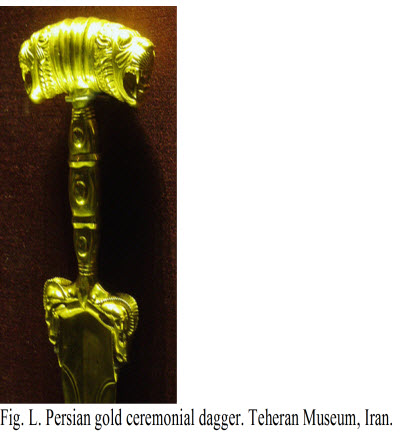

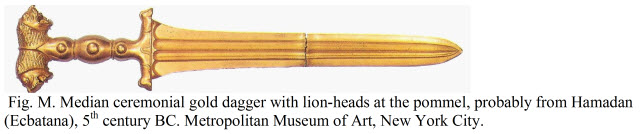

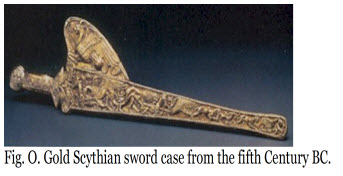

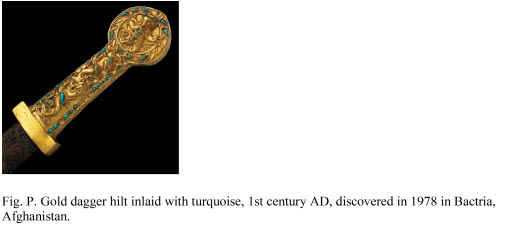

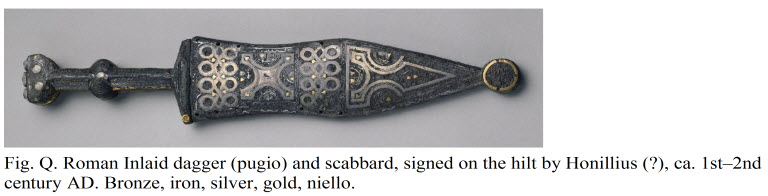

Other nations from Lehi’s time (ca. 600 BC) also had swords with gold hilts. These included Assyria, which fell to the Babylonians in 605 BC Fig. K); Persia, which conquered Babylon in 539 BC (Fig. L); the Medes, who joined with the Persians in the conquest of Babylon (Fig. M), and the Scythians, who migrated from Russia and Afghanistan to the Near East as far south as northern Israel in the 7th century BC (Figs. N-O). ((A. Palmieri, “Excavations at Arslantepe (Malatya),” Anatolian Studies 31 (1981): 101-119, 1981)) Later Mediterranean peoples, notably the Greeks and Romans, also decorated swords with gold. Various examples of swords resembling the one taken from Laban by Nephi were found after Joseph Smith’s time, yet the Book of Mormon testifies of a gold-hilted sword when such were as yet unattested in the biblical world before the age of modern archaeology.

Would the gold hilt have been some kind of indication of rank? Laban was a powerful official.

I don’t know if it was an indication of political or military rank, but it certainly was an indication of economic rank.

John,

I loved your article. Great research, as usual.

The fact that Nephi could recognize the fine qualities of Laban’s sword in the moonlight (or perhaps only starlight?) is evidence of Nephi’s metallurgical training and expertise. That Nephi used the word “most precious steel,” rather than “finest steel,” is an indication of the commercial value of the steel that was used, and therefore that kind of steel was available on the trading market. It was probably steel imported from Sparta, which was known for its exceptional hardness because of the natural manganese in their iron ore.

You mentioned that “the Egyptian weapon would not have been long enough for Nephi to strike off Laban’s head.” I concur with that. Nephi held up Laban’s head by his hair with one hand and “smote off his head” with Laban’s sword in his other hand. This tells us that it was a one-handed sword and that the blade was long enough and wide enough to have enough weight and momentum to take off a man’s head with one stroke.

You also mentioned the sword described in the “War Scroll” as being about 27 inches long and about 2 inches wide, which, with a heavy pommel at the back of the hilt, would have sufficient momentum for the task. A sword with a blade of that size would need a heavy pommel to provide balance for less strain on the wrist, and would give more force on impact. As gold is one of the heaviest metals, the gold hilt would be for utility as well as elegance.

There is no mention directly in the text that the Nephite swords, which were copied after the sword of Laban (2 Nephi 5:14), were two-edged swords, but the scalping of Zerahemnah gives us an indication that they were.

“And now when Moroni had said these words, Zerahemnah retained his sword, and he was angry with Moroni, and he rushed forward that he might slay Moroni; but as he raised his sword, behold, one of Moroni’s soldiers smote it even to the earth, and it broke by the hilt; and he also smote Zerahemnah that he took off his scalp and it fell to the earth. And Zerahemnah withdrew from before them into the midst of his soldiers.” (Alma 44:12)

Zerahemnah raised his sword to strike Moroni. The sword stroke of Moroni’s guard would have been a down-stroke to “smite” the broken sword to the earth. Zerahemnah is glancing down at his broken sword when the guard’s up-stroke took off his scalp; which “fell” to the earth. This scenario requires a two-edged sword. The Doctrine and Covenants states five times, that the word of the Lord is “sharper than a two-edged sword.” Joseph Smith added that phrase four more times to his translation of the Bible, which was done after he had seen the sword of Laban. Perhaps these are all references regarding the sword of Laban that the Lord was using as a symbol of His power.

The down-stroke force of the Nephite swords is also demonstrated when Ammon cut off the arms of his attackers at the waters of Sebus.

“…seeing that they could not hit him with their stones, they came forth with clubs to slay him. But behold, every man that lifted his club to smite Ammon, he smote off their arms with his sword; for he did withstand their blows by smiting their arms with the edge of his sword, insomuch that they began to be astonished, and began to flee before him; …and he smote off as many of their arms as were lifted against him, and they were not a few.” (Alma 17:36-38)

Though not mentioned in this instance, the Nephites also used shields in conjunction with their swords. When an attacker raised his club (stone tomahawk?) to strike Ammon, Ammon would have blocked the blow with his shield in one hand, and at the same time smote off the attacker’s raised arm at the elbow joint with a swift down-stroke of the sword in his other hand. This swift and powerful sword down-stoke is also demonstrated when Zerahemnah and his apostate Zoramites and Amalekites were surrounded by Moroni. These former Nephites “fought like dragons.” They smote in two many Nephite head-plates, and smote off many of their arms (Alma 43:44). The heavy down-stoke is also indicated when in this same battle “the bare heads of the Lamanites were exposed to the sharp swords of the Nephites” (Alma 44:18). The concept of the “sword hanging over” or above someone is a common theme in The Book of Mormon (Alma 48:14; 54:6; 60:29; Helaman 13:5; 3 Nephi 3:8). It appears that the down-stroke from a raised position was the preferred method of attack with the Nephite sword.

The Vikings swords of the 9th and 10th Centuries AD are very close to the description and use of the Nephite swords. Many Viking swords of that period have survived to our day and their unique design and method of use appears to be the same as the Nephite sword. Perhaps the Viking sword was patterned after the earlier Nephite sword, which was patterned after the Sword of Laban?

I have a battle-ready true replica of a 9th Century Viking sword made by “Windlass” of India. They are the people that make the US Marine Corps Ceremonial Swords. Its two-edged blade is 30 inches long and 2 inches wide, with a heavy pommel at the back of the hilt. No, the hilt is not made of pure gold. ☺

Theodore

While I also suspect Nephi was a skilled metal-smith, keep in mind that he wrote his account some 30-40 years after the events took place; the use of “most precious” may be retrospective rather than a recognition at that moment in time of the quality of the steel involved.

Possibly retrospect, but in context Nephi’s use of the past tense, “saw,” implies that was his impression at the time:

“And I beheld his sword, and I drew it forth from the sheath thereof…and I saw that the blade thereof was of the most precious steel.” (1 Nephi 4:9)

I was surprised that footnote one was not amplifted of the possibility that Laban’s sword descended from Joseph of Egypt along with the brass plates.