[Editor’s Note: Commentaries on the Book of Moses and Genesis Chapters 1 – 10 may be found on the ScripturePlus App from Book of Mormon Central and on the Bible Central website here.]

Jacob’s Preparations for His Encounter with Esau (Genesis 32:2–22)

In chapter 31, Leah and Rachel come together in a show of solidarity for Jacob’s plans to leave their family—and their father Laban’s selfish and greedy machinations—behind (Genesis 31:4–16). After a final contentious confrontation with Laban, Jacob manages to make peace with Laban and begins his return to Canaan (Genesis 31:43–54). But there is still a major threat that preoccupies Jacob. “Long-suppressed memories from his ignoble past intrude upon his consciousness. The specter of a vengeful Esau looms before him.”[2]

Jacob had no choice but move forward. But as he “went on his way,” he received the unexpected assurance of continued divine help. “The angels of God met him” (Genesis 32:2).

Robert Alter observes, “There is a marked narrative symmetry between Jacob’s departure from Canaan, when he had his dream of angels at Bethel, and his return, when again he encounters a company of angels.”[3] Indeed, “a law of binary division runs through the whole Jacob story: twin brothers struggling over a blessing that cannot be halved, two sisters struggling over a husband’s love, flocks divided into unicolored and particolored animals, Jacob’s material blessing [will be] divided into two camps”[4] before the encounter with Esau.

In light of Jacob’s previous experiences, another meeting with angels is not surprising. However, the significance of the reference to “Mahanaim” (“two hosts, or camps”[5])is less obvious. Meir Zlotowitz and Nosson Scherman understand it as a divine witness of the strength of Jacob’s family, the nascent nation of Israel that is about to enter the promised land:[6]

The Torah tells us how Jacob saw a company of angels as he finally left Laban and set out for Eretz Yisrael [Hebrew “Land of Israel”]. In their honor, he named the place Machanaim, literally two camps: his own camp and the angelic one (Genesis 32:3).

Grammatically, however, the proper form should have been … [Machanos], in the feminine plural form. But Jacob’s intention was not to indicate the numerical fact that there was more than one camp. Rather he meant to stress the quality of the two camps.

In Hebrew there is a special suffix which appears to be masculine, but actually connotes “pair of.” Thus, [Machanaim] means two times or a pair of times. … When two things are called a pair, the implication is that both items are identical, or at least similar.

Jacob saw before him two camps: that of his wives, children, and possessions; and that of the angels. Knowing observer that he was, he could assess the quality of the camps as well as their size. And he saw that they were a pair! The exterior of the angels was a garment that clothed God’s Presence—and so was the exterior of his family! Jacob had produced a family that was the parallel of the angels. In [Genesis 32] we will read of Jacob’s encounter with, and conquest of, an angel. That was Jacob—but his children? Yes, his children. Perhaps they could not triumph over angels as could their father, but the conqueror of angels had produced a family—a camp—that was the fitting equivalent on earth of an angelic camp above.

Despite the angelic assurance, “Jacob, ever a man of action takes precautionary measures [prior to his encounter with Esau.] First, he gathers intelligence [verses 4–7], then he prepares a stratagem of escape in the event of battle [verses 8–9]. This is followed by prayer [verses 10–13] and, finally, by the dispatch of a handsome gift [verses 14–22].”[7]

The most notable thing about Jacob’s preparations is the high quality of his prayer, imbued with confidence yet marked with humility. Unlike the tentative, bargaining language he employed in his vow at Beth-el (Genesis 28:20–22), his prayer is “an expression of absolute faith in a living God,”[8] beautiful but plainly spoken, free from artifice. It consists of “an invocation, a confession, a supplication, and a recollection:”[9]

9 And Jacob said, O God of my father Abraham, and God of my father Isaac, the Lord which saidst unto me, Return unto thy country, and to thy kindred, and I will deal well with thee:

10 I am not worthy of the least of all the mercies, and of all the truth, which thou hast shewed unto thy servant; for with my staff I passed over this Jordan; and now I am become two bands.

11 Deliver me, I pray thee, from the hand of my brother, from the hand of Esau: for I fear him, lest he will come and smite me, and the mother with the children.

12 And thou saidst, I will surely do thee good, and make thy seed as the sand of the sea, which cannot be numbered for multitude.

Source

Book of Genesis Minute by Jeffrey M. Bradshaw. For further reading, see Nahum M. Sarna, Genesis: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation Commentary, The JPS Torah Commentary, ed. Nahum M. Sarna (Philadelphia, PA: Jewish Publication Society, 1989), 223.

Related verses

Genesis 32:2–22

Genesis 32:24–32: A Wrestle with an Angel and the Promise of a New Name at Jabbok

Robert Alter points out that[10]

The image of wrestling has been implicit throughout the Jacob story: in his grabbing Esau’s heel as he emerges from the womb, in his striving with Esau for birthright and blessing, in his rolling away the huge stone from the mouth of the well, and in his multiple contendings with Laban. Now, in this culminating moment of his life story, the characterizing image of wrestling is made explicit and literal.

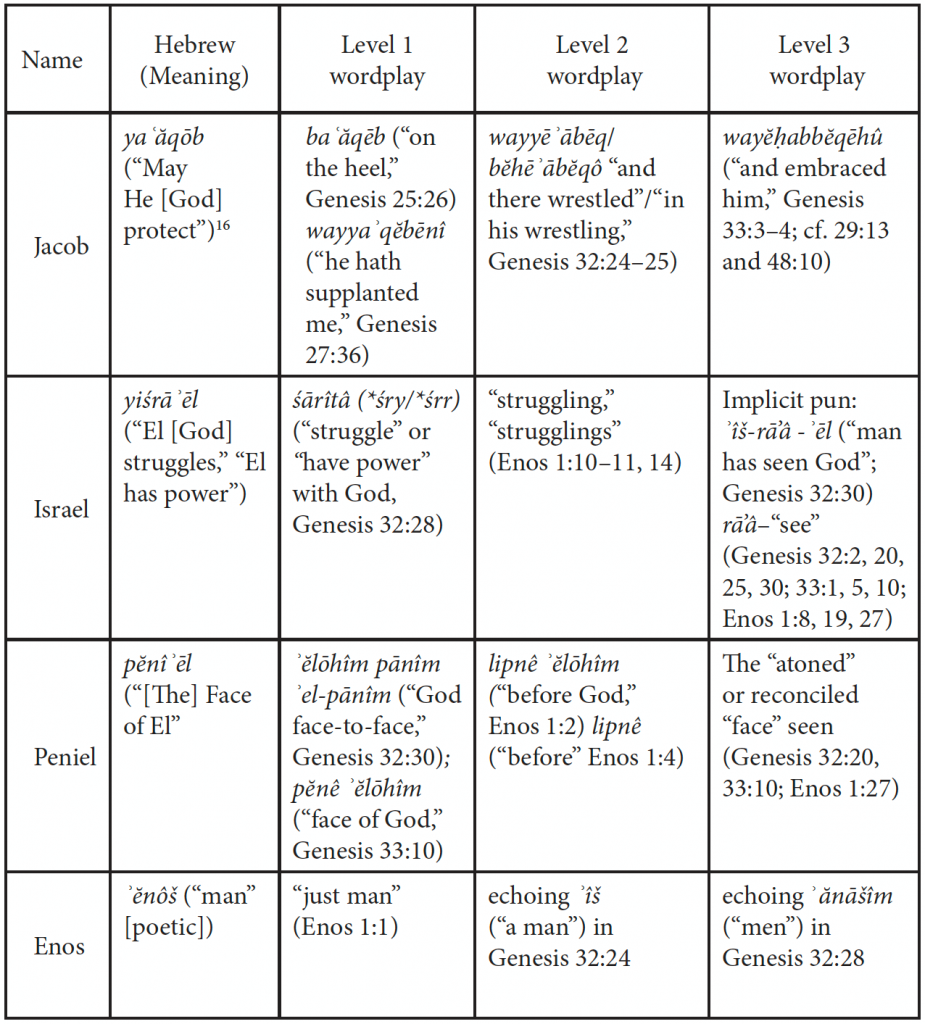

Matthew L. Bowen explains how, in this incident, the transformation of Jacob’s character is revealed through Hebrew wordplay:[11]

In the biblical account, the word “embraced” constitutes a paronomasia on the name Jacob[12] similar to the paronomasia on “wrestle” (yēʾābēq) and “Jacob” (yaʾăqōb). This wordplay is a sublime pun on “Jacob” that emphasizes his transformation from his former identity: he is no longer the “heel [-grabber]” or “usurper,” but “the embraced,” i.e., “the at-one-ed.” This pun confirms Hugh Nibley’s suggestion that “the word conventionally translated as ‘wrestled (yēʾāvēq)’ can just as well mean “embraced.”[13]

Bowen also points out that the very name of the brook where the event took place, Jabbok, also participates in the wordplay: “Jacob (yaʾăqōb) ‘passed over the ford Jabbok’ (yabbōq).”[14] He summarizes the complex Hebrew artistry in the table below, showing the remarkable affinities of the Genesis account with the story of Enos in the Book of Mormon.

Like the equally famous story of the Tower of Babel (Genesis 11:1–9), the whole episode unfolds in nine verses, tightly packed with both meaning and ambiguity. The density of the account warrants a careful phrase-by-phrase examination, drawing selectively from the large library of scholarship on this important incident.

Genesis 32:24: And Jacob was left alone. “He made repeated crossings of the river until all persons and goods had been safely transported. Now utterly alone in the dead of night, with no one to come to his aid, he must rely solely on his own resources.”[15] That he makes the extra effort to return to the north side of the river alone after having made everyone else go ahead of him hints that he as yet felt unprepared to go.

Genesis 32:24: and there wrestled a man with him until the breaking of the day. What kind of a wrestle was it? Describing the physical nature of the wrestle, Andrew C. Skinner comments:[16]

It seems reasonable to conclude that Jacob’s wrestle was physical as well as spiritual, because the text is emphatic in its description of Jacob’s dislocated hip (see Genesis 32:25, 31-32). Perhaps that detail is mentioned precisely to show that his wrestle was a literal as well as a metaphoric occurrence. It is also reasonable to suppose that Jacob’s opponent that night was a being from the unseen world of heavenly messengers, a divine minister possessing a tangible but translated body, because he was able to wrestle all night and throw Jacob’s hip out of joint (see Genesis 32:24-25).

Jacob’s opponent seems unlikely to have been a mere mortal because the text takes care to point out that there were no other humans close by (vv. 22-24). Note that the word ish (Hebrew “man”) refers to heavenly beings elsewhere in the Bible.

Describing the spiritual nature of such wrestles, Hugh Nibley writes:[17]

Nevertheless Alma labored much in the spirit, wrestling with God in mighty prayer” [Alma 8:10]. Wrestling with God? Does God resist you? Do you have to resist him? No, you have to put yourself into position, in the right state of mind. Remember, in our daily walks of life as we go around doing things, we’re far removed. If you’re bowling, or if you’re in business, or if you’re jogging or something like that, doing the things you usually do, and then you have to go from there to prayer, it’s quite a transition. It’s like a culture shock if you really take it seriously. You have to get yourself in form, like a wrestler having to look around for a hold or get a grip, as Jacob did when he wrestled with the Lord. You have to size yourself up, take your stance, circle the ring, and try to find out how you’re going to deal with this particular problem. You’re not wrestling with the Lord; you’re wrestling with yourself. Remember, Enos is the one who really wrestled [Enos 1:2]. And he told us what he meant when he was wrestling; he was wrestling with himself, his own inadequacies. How can I possibly face the Lord in my condition, is what he says. So this is what we’re doing.

However, in addition to the role of Jacob’s wrestle as a physical and spiritual test of his strength and character, there is a ritual aspect to the encounter. Jacob’s wrestle with the Lord’s messenger ends in a ritual embrace, in which Jacob, at first blush, seems to have been named and blessed. Hugh Nibley explained:[18]

One of the most puzzling episodes in the Bible has always been the story of Jacob’s wrestling with the Lord. When one considers that the word conventionally translated by “wrestled” (yē’āvēq) can just as well mean “embrace,” and that it was in this ritual embrace that Jacob received a new name and the bestowal of priestly and kingly power at sunrise (Gen. 32:24–30), the parallel to the Egyptian coronation embrace becomes at once apparent.

Genesis 32:25: And when he saw that he prevailed not against him, he touched the hollow of his thigh. Robert Alter translates “the hollow of his thigh” as the “his hip socket.”[19] As to the term “touched,” Alter notes:[20]

The verb naga‘ in the qal conjugation always means “to touch,” even “to barely touch,” and only in the pi‘el conjugation can it mean “to afflict.” The adversary maims Jacob with a magic touch, or, if one prefers, by skillful pressure on a pressure point.

Genesis 32:25: and the hollow of Jacob’s thigh was out of joint, as he wrestled with him. Despite his injury, “Jacob still refuses to let go.”[21]

Genesis 32:26: And he said, Let me go, for the day breaketh. Alter observes:[22]

This temporal limitation of activity suggests that the “man” is certainly not God Himself and probably not an angel in the ordinary sense. … But the real point, as Jacob’s adversary himself suggests[, is that] he refuses to reveal his name.

Genesis 32:26: And he said, I will not let thee go, except thou bless me. According to a Jewish midrash, “‘Blessing’ or congratulating one’s opponent was the accepted way of admitting defeat, and Jacob wanted the angel to admit defeat.”[23]

Genesis 32:27: And he said unto him, What is thy name? And he said, Jacob. Gordon J. Wenham offers the following explanation for the messenger’s question:[24]

To bestow a blessing, the blesser must know who he is blessing. But for an angel to ask Jacob’s name is superfluous. However, by divulging his name, Jacob also discloses his character. … In uttering his name Jacob admits he has cheated his brother (cf. “Is he not rightly called Jacob? He has tricked me these two times” [Genesis 27:36]).

Though there is merit to Wenham’s explanation, Andrew C. Skinner sees the question as part of a ritual question-answer dialogue:[25]

- Jacob was asked for his name, and he disclosed his own given name to a divine messenger or minister.

- Jacob was then presented with a new name.

- Jacob was next given [or, perhaps better, promised] an endowment of power, which would be recognized in the eyes of both God and men.

Genesis 32:28: And he said, Thy name shall be called no more Jacob, but Israel. Alter observes:[26]

Abraham’s change of name was a mere rhetorical flourish compared to this one, for of all the patriarchs Jacob is the one whose life is entangled in moral ambiguities. Rashi beautifully catches the resonance of the name change: “It will no longer be said that the blessings came to you through deviousness [‘oqbah, a word suggested by the radical of “crookedness” in the name Jacob] but instead through lordliness [serarah, a root that can be extracted from the name Israel] and openness.”[27] It is nevertheless noteworthy … that the pronouncement about the new name is not completely fulfilled. Whereas Abraham is invariably called “Abraham” once the name is changed from “Abram,” the narrative continues to refer to this patriarch in most instances as “Jacob.”

An explanation for the fact that this supposed name change did not really take effect until later is offered in Jewish midrash. Apparently, at Jabbok Jacob received a new name only in anticipation of a new name he would receive later from God Himself:[28]

It was not … the angel who was now renaming Jacob; nor was this name-change to be effective immediately, for the angel did not say, “no longer shall your name be called Jacob.’ The angel was merely revealing to Jacob what God Himself would do later. …

As Rashi continues the angel’s dialogue: ‘ … For later on, the Holy One, Blessed be He, will reveal Himself to you in Beth-el [see Genesis 35:10]. There He will change your name and bless you.

Another midrash adds: “In the Messianic time, however, the name Jacob will be given up entirely and only Israel [or, rather, the real and permanent new name represented by Israel in an anticipatory mode] will remain.”[29]

Genesis 32:28: Israel: for as a prince has thou power with God and with men and hast prevailed. Alter notes that the explanation of the name given in this verse does not square with its meaning. Though Jacob has indeed valiantly struggled, it is not he but God who will ultimately win out:

In fact, names with the ’el ending generally make God the subject, not the object, of the verb in the name. This particular verb, sarah, is a rare one, and there is some question about its meaning, though an educated guess about the original sense of the name would be: “God will rule,” or perhaps, “God will prevail.”

Genesis 32:29: And Jacob asked him, and said, Tell me, I pray thee, thy name. And he said, Wherefore is it that thou dost ask after my name? Wenham comments: “The ‘man’ now implicitly identified with God (se v. 29) refuses to give his name, lest it be abused (see Judges 13:17–18; Exodus 20:7) … Then he disappears in the dark as suddenly as he came.”[30]

Genesis 32:29: And he blessed him there. Skinner remarks that “the text is silent about the nature of the additional blessing.”[31] But Sarna, among others, seems to provide a better reading when he translates the phrase as “He took leave of him there.”[32]

Thus, we are left in doubt as to whether Jacob received or not, at that time, either the new name he sought or the blessing he had requested.[33]

Genesis 32:30: And Jacob called the name of the place Peniel: for I have seen God face to face, and my life is preserved. Nibley reads this verse as follows:[34]

And Jacob called the place Peniel [“the face of El”], because I have seen Elohim face to face and my spirit [nefesh, soul] has been saved [survived].

Genesis 32:31: And as he passed over Penuel. Penuel seems to be a simple name variant for Peniel.

Genesis 32:31: the sun rose upon him. “Jacob’s ignominious flight from home was appropriately marked by the setting of the sun; fittingly, the radiance of the sunrise greets the patriarch as he crosses back into his native land.”[35]

Genesis 32:21: and he halted upon his thigh. “Venerable Jewish tradition identifies this unique and cryptic term [for the thigh muscle] … with the sciatic nerve (nervus ischiadicus).”[36]

After the struggle with the divine messenger, Jacob limped away, badly injured. According to Alter: “Jacob, whose name can be construed as ‘he who acts crookedly,’ is bent, permanently lamed, by his nameless adversary in order to be made straight before his reunion with Esau.” [37]

President Russell M. Nelson has pointed attention to the role reversal reflected in the new name of Israel that will be given to Jacob.[38] In reviewing this reversal, Victor P. Hamilton observes that up until his “wrestle” with God in Genesis 32, “Jacob may well have been called ‘Israjacob,’ ‘Jacob shall rule’ or ‘let Jacob rule.’ In every confrontation he has emerged as the victor: over Esau, over Isaac, over Laban”[39]—and, startlingly, during the divine encounter at Jabbok he attempted to prevail in his conflict with God.

But after “God’s answer to the deceiver Jacob …, whereby God’s sovereignty and faithfulness to his promise despite all human unworthiness is demonstrated[,] Jacob is no longer the strong victorious controller of the divine but Israel who is totally dependent on God’s grace and lame.”[40]

Speaking of this “crucial turning point in the life of Jacob,” President Russell M. Nelson taught:

Through this wrestle, Jacob proved what was most important to him. He demonstrated that he was willing to let God prevail in his life. In response, God changed Jacob’s name to Israel (Genesis 32:28), meaning “let God prevail.” God then promised Israel that all the blessings that had been pronounced upon Abraham’s head would also be his (Genesis 35:11–12).

Source

Book of Genesis Minute by Jeffrey M. Bradshaw. For further reading, see Nahum M. Sarna, Genesis: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation Commentary, The JPS Torah Commentary, ed.

Nahum M. Sarna (Philadelphia, PA: Jewish Publication Society, 1989), 226–28.

Related verses

Genesis 32:24–32

Genesis 33:1–11: Jacob Embraces Esau and Receives Reconciliation with His Brother

Earlier, the “greatly afraid and distressed” (Genesis 32:7) Jacob had offered the most humble and impassioned prayer in his life in anticipation of his encounter with a potentially hostile Esau (Genesis 32:9–12). The “big surprise in the story of the twins” is that “instead of lethal [wrestling], Esau embraces Jacob in fraternal affection.”[41] His weakness having been turned to strength (see Ether 12:27), Jacob was now better prepared to shoulder the blessings and responsibilities of the house of Abraham.

Source

Book of Genesis Minute by Jeffrey M. Bradshaw. For further reading, see Nahum M. Sarna, Genesis: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation Commentary, The JPS Torah Commentary, ed.

Nahum M. Sarna (Philadelphia, PA: Jewish Publication Society, 1989), 229–30.

Related verses

Genesis 33:1–11

Jesus seems to allude directly to this event in his Parable of the Prodigal Son: “And he arose, and came to his father. But when he was yet a great way off, his father saw him, and had compassion, and ran, and fell on his neck, and kissed him” (Luke 15:20). The Lord, speaking to Enoch, describes a similar “at-one-ment” between Enoch’s Zion and the Latter-day Zion: “Then shalt thou and all thy city meet them there, and we will receive them into our bosom, and they shall see us; and we will fall upon their necks, and they shall fall upon our necks, and we will kiss each other” (Moses 7:63).

Trackbacks/Pingbacks