An Old Testament KnoWhy[1]

relating to the reading assignment for

Gospel Doctrine Lesson 21:

“God Will Honor Those Who Honor Him”

(1 Samuel 2-3; 8) (JBOTL21A)

Figure 1. Eli and Samuel

Question: Within the short space of one chapter, the boy prophet Samuel speaks the phrase “Here am I” five times.[2] Is there something more than meets the eye in his repeated reply?

Summary: Yes, when spoken in a spirit of meekness in response to a call from the Lord, it is not a simple assertion of availability but rather of humility and moral readiness. In this article, we will review a few instances of the phrase “Here am I” in scripture. With these examples in mind, we will examine the story of Samuel’s call verse-by-verse — and its implications for our own responses to God’s invitations to serve. Modern photographs and descriptions of the ancient site of Shiloh, where the building housing the Tabernacle once stood, are included at the end of the article.

The Know

The call of the lad Samuel by the Lord is a scriptural gem. It has been called[3] “a remarkably finely crafted chapter. Several rare words are set together, illuminating each other and reflecting flashes of light from more distant parts of the [Bible]. … [T]he stage set is very carefully explored with much slower deliberation than is common in biblical narrative.[4] … Nothing happens till the Lord calls.”[5]

The focus of this article will not be so much on the Lord’s call as on Samuel’s response: “Here am I.” The same reply is repeated, with interesting differences, by other biblical prophets[6] — and also by a few false pretenders.[7]

The Response As a Window Into the Heart

A call from the Lord opens a window into the heart of the respondent. Some object to their call — feeling unworthy or unfit.[8] Others feign worthiness, craving the merits of God’s favor while seeking their own selfish ends.[9] A relative few respond reflexively in the correct spirit of the phrase “Here am I” with simple humility and childlike guilelessness, feeling their weakness yet made ready by their faith in God to hear and obey.[10]

Importantly, Elder Neal A. Maxwell taught that “feeling unworthy, unready, and uncertain about what we can contribute, when so called, is different from questioning the call itself.”[11] For example, in Enoch’s “honest questions … there was a sense of unpreparedness but not an unwillingness. … [God] needs our meekness … in order to part the curtains of our understanding.”[12] Thus, before Enoch could receive a vision of eternity, he needed to receive “a new vision of himself.”[13]

On the other hand, Satan’s response to the Father’s call manifested a very different spirit:[14]

Behold, here am I, send me, I will be thy son, and I will redeem all mankind, that one soul shall not be lost, and surely I will do it; wherefore give me thine honor.

Richard D. Draper, S. Kent Brown, and Michael D. Rhodes note that the statement “here am I, send me” carries the implicit claim “that the speaker is in the right path, ready to do the Lord’s bidding.”[15] However, the fact that Satan’s intent was to directly oppose God’s plan undermined his claim of moral readiness and substantiated the scriptural statement that he is “a liar from the beginning.”[16]

Satan’s self-centeredness is fittingly reflected in the full wording of his proposal. With passionate rapid-fire delivery, he narcissistically repeats the terms “I” and “me” six times in the short span of half a verse.[17] The original manuscripts of the Joseph Smith Translation reinforce the stylistic egoism of Satan’s reply of “Behold, here am I” with a briefer reading: “Behold I.”[18] Significantly, the Prophet’s inspired dictation matches a literal English translation of “Behold, here am I” in biblical Hebrew: hinne-ni (Behold, I).[19]

The Devil had the right words down pat, but his heart reeked of duplicity.

In response to God’s call to sacrifice his son Isaac, Abraham became the first Old Testament prophet known to have answered with the words “Behold, here I am.”[20] Erich Auerbach observes that the reply is “not meant to indicate the actual place where Abraham is but a moral position in respect to God, who has called to him — Here am I awaiting thy command.”[21]

Jewish tradition goes further, specifically linking Abraham’s earnest reply to his desire for the “blessings of the fathers”[22] that he so earnestly sought and eventually received:[23]

Now Abraham said, “Here am I” — ready for priesthood, ready for kingship, and he attained priesthood and kingship. He attained priesthood, as it says, “The Lord hath sworn, and will not repent: Thou art a priest for ever after the manner of Melchizedek”;[24] kingship: “Thou art a mighty prince among us.”[25]

With these examples in mind, we will examine the story of Samuel’s call verse-by-verse — and its implications for our own responses to God’s invitations to serve.

Figure 2. The Dedication of Samuel

The Call of Samuel (1 Samuel 3)

1. And the child Samuel ministered unto the Lord before Eli. And the word of the Lord was precious in those days; there was no open vision.

the child Samuel. Samuel was likely older than he is usually pictured in common Bible illustrations. The Hebrew term used is na’ar (נַעַר), often translated elsewhere as “lad” or “youth,” as in the stories of Enoch’s call and David’s combat with Goliath. Fox says the term can mean “either a child or a teenager.”[26] I picture Samuel at the time of his call being about the same age of Joseph Smith when he received the First Vision.

the word of the Lord was precious in those days. Clarifying the meaning of this phrase, the Targum of Samuel reads: “the word of the Lord was hidden in those days; no prophecy was revealed.”[27] According to Robert Alter, the phrase indicates that “there is some sort of breakdown in the professional performance of the house of Eli.”[28] Thus, a primary purpose of the chapter is to announce that things are about to change: the gift of prophecy is about to return through the ministry of Samuel, the “faithful priest”[29] whose coming had just been announced to Eli by “a man of God”[30] at the end of chapter 2.

2. And it came to pass at that time, when Eli was laid down in his place, and his eyes began to wax dim, that he could not see;

Eli was laid down in his place. As a priest descended from Aaron, Eli’s duty is to sleep in the Tabernacle.[31] Night was “a frequent time for revelations in the Bible and the ancient Near Eastern world,”[32] but he is blind and deaf to the word of the Lord. Thus, though he physically sleeps “in his place” within the “terrestrial room” of the sanctuary, he is, as it were, spiritually outside it — in the “world room” of the Tabernacle courtyard with the Levites.[33] In Job 33:14-16, we read:

God speaketh once, yea twice, yet man perceiveth it not.

In a dream, in a vision of the night, when deep sleep falleth upon men, in slumberings upon the bed;

Then he openeth the ears of men, and sealeth their instruction.

In verse 9, we learn Samuel, like Eli, is also lying “in his place.”[34] But Samuel’s place, unlike Eli’s, is “near the Ark of God from where God’s voice is heard.”[35]

his eyes began to wax dim, that he could not see. Alter comments: “Eli’s blindness … reflects [not only] his decrepitude but [also] his incapacity for vision. … He is immersed in permanent darkness while the lad Samuel has God’s lamp burning by his bedside.”[36]

Besides Eli’s inability to “see afar off”[37] by the lamp of the visions of prophecy, he fails to “see” the urgency to more effectively restrain his two wicked sons.[38] Indeed, the same Hebrew word for “wax dim” in verse 2 is used again in verse 13 with reference to Eli’s failure to correct his sons, thus making an explicit connection between Eli’s “failing eyesight” and his “lack of insight.”[39] In short, the weakening of Eli’s vision will lead, inevitably, to the death of his sons and the end of his priestly lineage.[40]

The offense of Eli’s sons is of the gravest sort, a sort that will ring[41] with painful horror when it is made known in the ears of all the people:[42]

The Masoretic Text reads, “his sons have been scorning for themselves [lahem],” but the last Hebrew word has long been recognized as a tiqun sofrim, a scribal euphemism for Elohim, God — that is, the scribes were loath to write out so sacrilegious a phrase as scorning, or cursing, God.[43] The verb here is commonly used in the sense of “to damn” or “to express contempt.”

Figure 3. The structure that housed the Tabernacle at Shiloh

3. And ere the lamp of God went out in the temple of the Lord, where the ark of God was, and Samuel was laid down to sleep;

ere the lamp of God went out. The golden lampstand, in the Holy Place of the Tabernacle, was to be filled with pure olive oil and kept alight throughout the night.[44] In addition to the lampstand, the altar of incense stood immediately in front of the veil and represented the sweet savor of the prayers of the righteous.[45] At twilight, the appointed priests were to assure both that the lampstand was lit and also that incense was burning upon the altar.[46] It is not improbable that Samuel, in preference to the sons of Eli, had been assigned these duties.

The phase “ere the lamp of God went out” seems to imply, in a literal sense, that the call of Samuel took place not long before dawn. But Alter notes that “the symbolic overtones of the image should not be neglected: though vision has become rare, God’s lamp has not yet gone out, and the young ministrant will be the one to make it burn bright again.”[47] Hauntingly, the reference to the lamp that was not yet “out” at the time of Samuel’s call anticipates the horrible fears of David’s friends, in a later chapter of the book of Samuel, that their chieftain’s death might extinguish the lamp of Israel once and for all.[48]

where the ark of God was. Unlike the lampstand and the altar of incense that stood outside the veil, the Ark was kept in the Holy of Holies. The implication of verses 3 and 4, made explicit in the Targum,[49] is that the voice of the Lord spoke from the invisible throne of God above the Ark — in other words, from behind the veil. Though the veil hid the Ark from view, the spiritually perceptive Samuel, sleeping nearby, could clearly hear the voice that emanated therefrom,[50] even if he was mistaken in thinking it came from the direction of Eli.

4. That the Lord called Samuel: and he answered, Here am I.

5. And he ran unto Eli, and said, Here am I; for thou calledst me. And he said, I called not; lie down again. And he went and lay down.

6. And the Lord called yet again, Samuel. And Samuel arose and went to Eli, and said, Here am I; for thou didst call me. And he answered, I called not, my son; lie down again.

7. Now Samuel did not yet know the Lord, neither was the word of the Lord yet revealed unto him.

the Lord called Samuel. Though Eli and Samuel both slept in the Tabernacle, only Samuel heard the Lord’s voice that night. The circumstances recall Moroni’s nighttime appearance to Joseph Smith.[51] Despite the fact that the Prophet shared a bed with siblings, he was the only one who saw and heard the Nephite prophet speak to him.

And he ran unto Eli, and said, Here am I; for thou callest me. The fact that Samuel “ran unto Eli” is evidence that his initial answer was “not a direct response to God. … Samuel’s thrice-repeated error in this regard reflects not only his youthful inexperience but [also] the general fact that ‘the world of the Lord was rare,’ revelation an unfamiliar phenomenon.”[52]

I called not, my son. Alter comments: “Until this point, we have been told nothing about Eli’s relationship with Samuel. The introduction of this single term of affection, ‘my son,’ reveals the fondness of the blind and doomed Eli for his young assistant. His own biological sons have of course utterly betrayed his trust.”[53]

Samuel did not yet know the Lord. 1 Samuel 2:12 had already stated that the sons of Eli “knew not the Lord.” Out of reverence for Samuel, the Targum did not want to assert that Samuel was as “ignorant as Eli’s sons,”[54] so it paraphrased the Hebrew to read “Samuel had not yet learned to recognize instruction from before the Lord.”[55]

8. And the Lord called Samuel again the third time. And he arose and went to Eli, and said, Here am I; for thou didst call me. And Eli perceived that the Lord had called the child.

9. Therefore Eli said unto Samuel, Go, lie down: and it shall be, if he call thee, that thou shalt say, Speak, Lord; for thy servant heareth. So Samuel went and lay down in his place.

Eli perceived that the Lord had called the child. Although the Lord’s call had been addressed to Samuel, Eli will be first to recognize what is happening.[56]

Figure 4. Harry Anderson: Speak; for thy servant heareth

10. And the Lord came, and stood, and called as at other times, Samuel, Samuel. Then Samuel answered, Speak; for thy servant heareth.

And the Lord came, and stood. Although depictions of the physical presence of God are found in several other places in the Bible,[57] this “very human description of God” literally standing to speak to Samuel “made later readers somewhat uncomfortable.”[58]

In addition, while it is “commonplace in the Bible for humans (or even divine beings, as in Job 1) to ‘take their stand’ before Yahweh,” the opposite is rare. In part, this is due to the fact that the Hebrew term commonly used for this position, ‘amad lifnei (stand before), “is language of subordination.”[59] For example, Deuteronomy 10:8[60] describes the duties of the Levites as being “to bear the ark of the covenant of the Lord, to stand before the Lord to minister unto him,[61] and to bless in his name.”[62] In other words, their office was to stand and serve —not to be served.[63]

Samuel, Samuel. The Lord’s words to Samuel are now reported directly in dialogue rather than in impersonal, third-person style (i.e., v. 4: “the Lord called Samuel”).[64] The name of Samuel is repeated twice by the Lord, just as it was at important junctures in the lives of Abraham and Moses.[65]

Speak; for thy servant heareth. Remarkably, having repeated four times the usual prophetic response of “Here am I” earlier in the chapter, Samuel’s first knowing reply to the Lord took a different form — unknown elsewhere in similar encounters in scripture. Of course, the simple explanation for this deviation is that these were (with one slight exception[66]) the same words that Eli had instructed Samuel to say. But because the word for “heareth” (shama’) is similar to the word for “Samuel” (Shemuel) some wordplay also may be involved.

What is most important to note, however, is that “God’s words to Shemuel do not, as so often in biblical ‘call’ narratives, require answer and dialogue. Young Shemuel appears in this chapter as one through whom God speaks, and is thus a prophet, but there is none of the usual tension between the one called and the burden he is asked to carry — at least for the moment — that we find elsewhere in the Bible.”[67] Despite the fearful prospect of recounting the Lord’s words to Eli, Samuel listens in silent acceptance of the divine will.

Arising from his bed in the morning, Samuel opened the doors to the Tabernacle, thus continuing “to carry out his daily duties as usual.”[68] And when the old priest called to talk with him, Samuel answered to him as he had every time the night before with the words “Here am I.”[69]

After having heard Samuel’s report, Eli’s response is characteristically passive. Instead of falling on his face and pleading for the Lord’s forgiveness and direction, he accepts the word of the Lord humbly but fatalistically. Likewise, when the repentant but still sin-wracked David could no longer find the faith to hope that the Lord would deliver him, he replied with sad resignation: “here am I, let [the Lord] do to me as seemeth good unto him.”[70]

Figure 5. Jean Jacques Tissot: The Death of Eli

Summary and Aftermath

Everett Fox gives the following summary and aftermath of the story of Samuel’s call, emphasizing that it was no coincidence that the book began with the account of the prayer of Samuel’s faithful mother Hannah and that her psalm of praise summarizes what will become major themes throughout 1 and 2 Samuel:[71]

Hanna [Hannah] makes a telling contrast to the High Priest, Eli, continuing a pattern that recurs throughout Judges and Samuel, where women provide a [contrast] and a profound sounding board for issues of power.

It is worth noting, as many have, that Hanna’s poem in chapter 2 … is a prelude to major themes of the book, especially the idea that God, the great Reverser [who sets things right], may choose to exalt the powerless. YHWH [Jehovah], who “brings down … and brings up” (v. 6), will be directing the fate of Israel and its early kings, and while he will in the end “give power to his king” (v. 10), he will also make it clear that “not by might does a man prevail” (v. 9).

The priest-judge Eli, an ineffective leader, typifies an era that is coming to a close. His first act, mistaking Hanna’s deep inner religiosity for drunkenness, sets the tone. Unlike his young charge Shemuel, he is never in direct verbal contact with God; in addition, he is incapable of providing the military leadership of his predecessors, and, most tellingly, unable to control the highly inappropriate behavior of his sons. Barely noticeable amid Eli’s initial bluster in chapter 1 is a striking detail: he sits on a kind of “throne.” The first part of this section of the book (chapters 1-4) will end with his death in that very seat, overturned when he hears the disastrous news of the Ark’s capture. The fall of the house of Eli gives way to the leadership of his judge-prophet successor, Shemuel.

Auld summarizes: “Samuel is to Eli as David will be to Saul.”[72]

The Why

When we are called of God, He works with us in our imperfections. Those who are proud and think that they can succeed because of their own talents and abilities soon find themselves very wrong. President Spencer W. Kimball taught: “The mighty and vain and noble and brilliant are not called because they are unteachable, sometimes. They feel they know so much that God cannot teach them.”[73] In a similar vein, we read the following in JST I Corinthians 1:26-28:

26 For ye see your calling, brethren, how that not many wise men after the flesh, not many mighty, not many noble, are chosen.

27 But God hath chosen the foolish things of the world to confound the wise; and God hath chosen the weak things of the world to confound the things which are mighty;

28 And base things of the world, and things which are despised, hath God chosen, yea, and things which are not, and to bring to nought things that are mighty.

What is important is that whenever the Lord calls and whatever He asks us to do, we respond sincerely and without objection in the true spirit of “Here am I.”

Once I was assigned to visit an elderly couple who had served in many positions of prominence in the Church. The picture of them seated together on the couch in their modest home is still vivid in my mind. I had been asked to extend a call to the sister to be the accompanist for the ward choir. The faithful sister could have objected that they had already put in their time and that now, in their later years, had a right to retire from church service, but she accepted the calling graciously. Over the course of their lives they had become the kind of great souls they were by accepting callings of all kinds, from the kinds of callings that require great sacrifice of time and means, to those that are so much less visible and so seemingly mundane that some might think them unworthy of their talents.

Over the years, my admiration has continued to grow for faithful members such as this couple that Elder Boyd K. Packer called “the rank and file of the Church”[74] and that President J. Reuben Clark called “them of the last wagon.”[75] Their quiet service and willingness to serve wherever they are called is a measure of the degree of their conversion and understanding that the purpose of life for each of us is to fulfill the unique mission on the earth to which each of us has been assigned. I love the way this is expressed in a poem by Meade MacGuire:[76]

Father, where shall I work today?”

And my love flowed warm and free.

Then he pointed out a tiny spot

And said, “Tend that for me.”

I answered quickly, “Oh no, not that!

Why, no one would ever see,

No matter how well my work was done.

Not that little place for me.”

And the word he spoke, it was not stern;

He answered me tenderly:

“Ah, little one, search that heart of thine;

Art thou working for them or for me?

Nazareth was a little place,

And so was Galilee.

My love and gratitude to my wife Kathleen for her suggestions on this article and for her unwearied willingness to serve wherever she is called.

Archaeological Remains of Ancient Shiloh

Figure 6. Ruins of ancient Shiloh on Tel Shiloh (Khirbet Seilun), West Bank.[77] The site is near modern Seilun, 18 kilometers south of Nablus. The site was reoccupied from about 1200 BCE until about 1050 BCE when the area was burned, correlating to events in 1 Samuel 4. The city was later rebuilt, then abandoned again after the Assyrian conquest in 722 BCE. Off and on occupation continued for many centuries afterward. Opened in 2014, the “HaRo’eh Tower” (“Tower of the Seer” from Hebrew רֹאֶה, ro’eh = seer, referring to Samuel[78]) now sits atop the tel, the first among many large projects that are being undertaken to increase tourism at the site. Israel Finkelstein has proposed that the Tabernacle was housed on the summit of the tel.

Figure 7. Some traditions see the location of the Tabernacle as being on the slopes north of Tel Shiloh. Cultic usage of the site persisted over many centuries.[79]

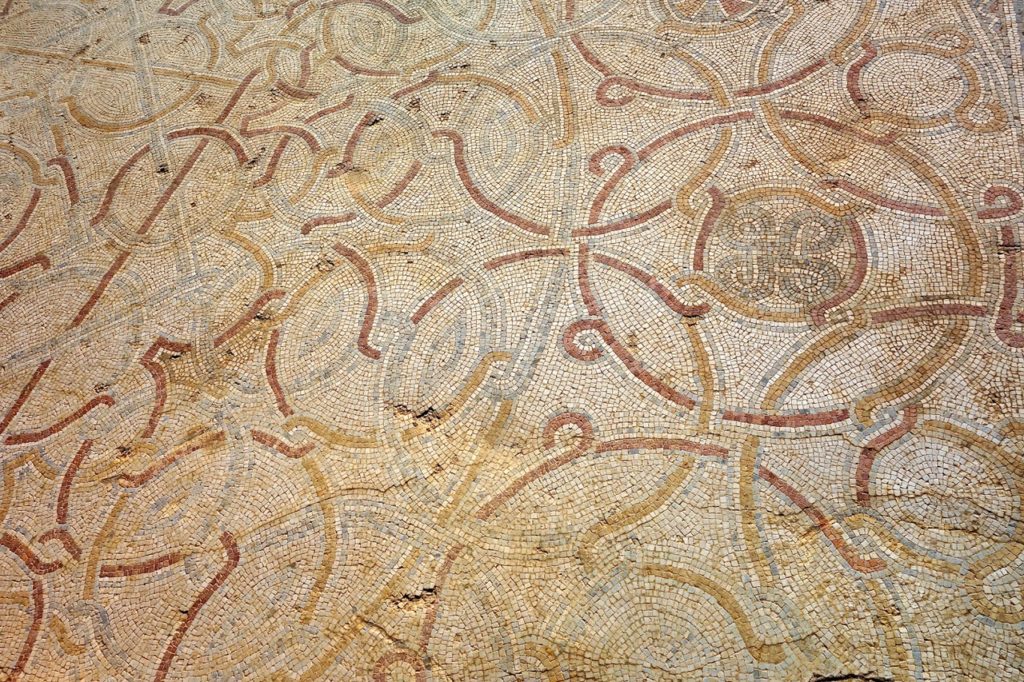

Figure 8. Mosaic floors from a Byzantine church were found underneath the foundation of the Mosque of the Orphan (Jama al-Yatim). Some, especially Christians, tend to identify the location of the Tabernacle with this general area, just south of Tel Shiloh. One of the inscriptions on the Byzantine mosaic floors included a prayer (inset): ” … have compassion for the people of Shilo” (CIλOYN = Siloun)[80]

Figure 9. Portion of mosaic floor in Byzantine Church[81]

Further Study

For other scripture resources relating to this lesson, see The Interpreter Foundation Old Testament Gospel Doctrine Index (https://interpreterfoundation.org/gospel-doctrine-resource-index/ot-gospel-doctrine-resource-index/) and the Book of Mormon Central Old Testament KnoWhy list (https://knowhy.bookofmormoncentral.org/tags/old-testament).

References

Alter, Robert, ed. The David Story: A Translation with Commentary of 1 and 2 Samuel. New York City, NY: W. W. Norton, 1999.

Auerbach, Erich. 1946. Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature. Translated by Willard R. Trask. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013.

Berlin, Adele, and Marc Zvi Brettler, eds. The Jewish Study Bible, Featuring the Jewish Publication Society TANAKH Translation. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. "Standing in the Holy Place: Ancient and modern reverberations of an enigmatic New Testament prophecy." In Ancient Temple Worship: Proceedings of the Expound Symposium, 14 May 2011, edited by Matthew B. Brown, Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, Stephen D. Ricks and John S. Thompson. Temple on Mount Zion 1, 71-142. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014. http://www.templethemes.net/publications/04-Ancient%20Temple-Bradshaw.pdf.

———. Temple Themes in the Oath and Covenant of the Priesthood. 2014 update ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and Matthew L. Bowen. "”By the Blood Ye Are Sanctified”: The Symbolic, Salvific, Interrelated, Additive, Retrospective, and Anticipatory Nature of the Ordinances of Spiritual Rebirth in John 3 and Moses 6." Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 24 (2017): 123-316. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/by-the-blood-ye-are-sanctified-the-symbolic-salvific-interrelated-additive-retrospective-and-anticipatory-nature-of-the-ordinances-of-spiritual-rebirth-in-john-3-and-moses-6/. (accessed January 10, 2018).

Clark, E. Douglas. The Blessings of Abraham: Becoming a Zion People. American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 2005.

Clark, J. Reuben, Jr. 1947. "To them of the last wagon (October 5, 1947)." In J. Reuben Clark: Selected Papers on Religion, Education, and Youth, edited by David H. Yarn, Jr., 67-74. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1984. Reprint, Ensign, July 1997, pp. 34-39.

Danby, Herbert, ed. The Mishnah. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1933.

Dew, Sheri L. No Doubt About It. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 2001.

Draper, Richard D., S. Kent Brown, and Michael D. Rhodes. The Pearl of Great Price: A Verse-by-Verse Commentary. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005.

Dunn, James D. G., and John W. Rogerson. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2003.

Faulring, Scott H., Kent P. Jackson, and Robert J. Matthews, eds. Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible: Original Manuscripts. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2004.

Fisch, Harold. The Biblical Presence in Shakespeare, Milton, and Blake: A Comparative Study. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press, 1999.

Fox, Everett. The Early Prophets: Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings. The Schocken Bible 2. New York City, New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2014.

Freedman, H., and Maurice Simon, eds. 1939. Midrash Rabbah 3rd ed. 10 vols. London, England: Soncino Press, 1983.

Jackson, Kent P. The Book of Moses and the Joseph Smith Translation Manuscripts. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Religious Studies Center, 2005. https://rsc.byu.edu/archived/book-moses-and-joseph-smith-translation-manuscripts. (accessed August 26, 2016).

Kimball, Spencer W. The Teachings of Spencer W. Kimball. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1982.

Lyon, Jack M., Linda Ririe Gundry, Jay A. Parry, and Devan Jensen, eds. Best-Loved Poems of the LDS People. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1996.

Maxwell, Neal A. Wherefore, Ye Must Press Forward. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1977.

———. Men and Women of Christ. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1991.

Milgrom, Jacob. Numbers. The JPS Torah Commentary, ed. Nahum M. Sarna and Chaim Potok. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society, 1990.

Packer, Boyd K. "A tribute to the rank and file of the Church." Ensign 10, May 1980, 62-65. https://churchofjesuschrist.org/general-conference/1980/04/a-tribute-to-the-rank-and-file-of-the-church?lang=eng. (accessed May 28, 2018).

Rashi. c. 1105. The Torah with Rashi’s Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated. Vol. 5: Devarim/Deuteronomy. Translated by Rabbi Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg. ArtScroll Series, Sapirstein Edition. Brooklyn, NY: Mesorah Publications, 1998.

Smith, Joseph, Jr. The Words of Joseph Smith. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1980. https://rsc.byu.edu/archived/words-joseph-smith-contemporary-accounts-nauvoo-discourses-prophet-joseph/1843/21-may-1843. (accessed February 6, 2016).

Tigay, Jeffrey H., ed. Deuteronomy. The JPS Torah Commentary, ed. Nahum M. Sarna and Chaim Potok. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society, 1996.

Van Staalduine-Sulman, Eveline. The Targum of Samuel. Studies in the Aramaic Interpretation of Scripture 1, ed. Paul V. M. Flesher. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

Endnotes

Of course, sometimes an equivalent reply can be given using different words. For example, the reply of Mary in Luke 1:38 certainly is made in the same spirit as Abraham’s reply: “Behold the handmaid of the Lord; be it unto me according to thy word.”

Similarly, Joseph Smith stated that by the “oath of God unto our Father Abraham,” his children were “secured [to him] by the seal wherewith [Abraham had] been sealed” (J. Smith, Jr., Words, 13 August 1843, p. 241). In the greatest irony of Abraham’s life, only by binding Isaac for the sacrifice had Abraham bound him to himself in the eternal bonds of priesthood sealing.

8. The Chamber of the Hearth^ was vaulted; it was a large chamber and around it ran a raised stone pavement; and there the eldest of the father’s house used to sleep with the keys of the Temple Court in their hand. The young priests had each his mattress on the ground.

9. And there was a place there, one cubit square, whereon lay a slab of marble in which was fixed a ring and a chain on which hung the keys. When the time was come to lock up [the Temple Court] he lifted up the slab by the ring and took the keys from the chain. And the priest locked [the gates] from inside while a levite slept outside. When he had finished locking [the gates] he put back the keys on the chain and the slab in its place, put his mattress over it, and went to sleep. If one of them suffered a pollution he would go out and go along the passage that leads below the Temple building, where lamps were burning here and there, until he reached the Chamber of Immersion. R. Eliezer b. Jacob said: He used to go out by the passage that leads below the Rampart and so he came to the Tadi Gate.

The Hebrew kihah occurs only here as a transitive verb in the pi’el conjugation, though it is fairly common as an intransitive verb in the qal conjugation, meaning “to grow weak,” “to become dark,” or, as with the eyes of Eli in verse 2, bleary. The transitive sense of the verb would then be something like “to incapacitate,” to prevent someone from doing something. Its unusual usage in this sentence is obviously meant to align Eli’s failing in parental authority with the failing of his sight.