An Old Testament KnoWhy[1]

relating to the reading assignment for

Gospel Doctrine Lesson 19: The Reign of the Judges

(Judges 2; 4; 6-7; 13-16) (JBOTL19A)

Figure 1. Details of Saturn’s atmosphere and rings[2]

Question: The Bible account of Creation explains very little about the formation of the solar system or the biological origin of life. Archaeological evidence sometimes directly contradicts it, its laws of diet and purity seem irrelevant, and its prophecies are largely unintelligible. Why should I spend my time studying the Old Testament when I could be focusing my attention instead on up-to-date history and science or on the practical, ethical teachings of Jesus that teach us how we should live?

Summary: Having most recently discussed archaeological findings that relate to the books of Joshua and Judges, and having written prior to that on the historical context of the Exodus, I would now like to consider the larger question of why and how one might study the Old Testament. Specifically, in this article, I will explain why I think it is important to counterbalance the study of scripture in its historical and scientific context with traditional forms of scripture reading. First, it should not be forgotten that the Old Testament provides essential background not only for Jesus’ teachings on how we should live from day to day but also on His words about the meaning and purpose of life from an eternal perspective. Relatively little of the rest of scripture — whether ancient or modern — can be adequately understood without reference to its Old Testament backdrop. Sadly, given the common tendency today to treat the stories of the Old Testament as targets of humor and caricature (when they are not ignored altogether),[3] it is difficult for some people to take them seriously. However, serious study of the Old Testament will reveal not merely tales of “piety or … inspiring adventures”[4] but in addition carefully crafted narratives from a highly sophisticated culture that frequently preserve “deep memories”[5] of doctrinal understanding. We do an injustice both to these marvelous records and to ourselves when we treat them merely as pseudo-science, botched history, or careless editorial paste-up jobs. A doctrinal perspective on the Old Testament should always remain central to our efforts to appreciate and understand it, even while acknowledging the significant enrichment that historical, scientific, and textual studies can provide in a secondary role.

Figure 2. “The Simses of Old Greenwich, Conn., gather to read after dinner. Their means of text delivery is divided by generation.”[6] And often, most of what they consume is video and images rather than text. Photograph by Nichole Bengiveno

The Know

Challenges in Reading Scripture Today

Despite the blessing of wider availability of the scriptures than ever before, Church members today face significant challenges in reading them. Of course, the most important of these challenges are spiritual in nature — the requirements of worthiness to receive revelation and willingness to apply it. In addition, however, there are practical challenges that put current generations at a disadvantage in acquiring the basic understanding of scripture that precedes revelation and application. Here are a few of these practical challenges.

Limited vocabulary and reading skills. At the most basic level, many important scriptural terms (significantly including temple-related terms such as “endow,” “seal,” “mystery,” “key,” “sign,” “token,” “calling,” and “election”) have changed in meaning since the early days of the Restoration.[7] In other cases, the words have completely dropped out of our everyday vocabulary.

Besides these challenges at the level of the words, some preliminary evidence seems to indicate that those of us who feed largely on media may read differently than those of previous generations.[8] For one thing, we have become accustomed to a kind of reading that consists of facile skimming for rapid information ingestion — what the great Jewish scholar Martin Buber went so far as to term “the leprosy of fluency.”[9]

For another thing, even if one had the time and patience to read more reflectively, many today lack the capacity to follow the logic of passages that are longer than a sound bite, treating complex descriptions or lines of argument as grab bags of simple, unordered, atomic associations rather than as linear structures that were carefully composed by divinely inspired authors of scripture to serve specific literary, expository, or revelatory purposes.[10]

It cannot be doubted that our difficulties in grasping the larger logic of scripture that binds phrases and sentences together into coherent passages, especially within the doctrinal expositions (versus the stories) of scripture, are at least partly behind what Prothero calls a widespread “religious amnesia” that has dangerously weakened the foundations of faith.[11]

Selective reading. Sadly, scriptures are not the staple of literary and religious life in our day that they were to those who lived in Joseph Smith’s time. When we do study the scriptures, we read not only quickly but selectively, spending much more time on chapters we learned to love as children than on passages we do not enjoy and have never really understood. Many misunderstandings could be avoided by sequential reading of the scriptures in their entirety, start to finish.

Fortunately, we are blessed to have an abundance of revelations and teachings from latter-day prophets. Through their inspired commentary, and the required companionship of the Holy Ghost, “the scriptures [may be] laid open to our understandings, and the true meaning and intention of their more mysterious passages [may be] revealed unto us in a manner which we never could attain to previously, nor ever before had thought of.”[12]

One of Joseph Smith’s frequent teaching methods was to take an obscure or misunderstood passage of scripture and unfold new meanings to his listeners, drawing on both his familiarity with an astonishing number of scriptural passages[13] and also on the prophetic insights he had gained firsthand through divine revelation. His language was often loaded with localisms, creative allusions, and scriptural wordplay.[14] However, the frequent allusions the Prophet made to scripture and other sources will never be recognized, let alone understood, unless we are familiar with these texts ourselves.[15]

Doctrinal ignorance. When scripture is consulted at all, it is too often “solely for its piety or its inspiring adventures”[16] or its admittedly “memorable illustrations and contrasts” rather than the “deep memories” of doctrinal understanding that provide context for the imagery and are woven throughout the stories themselves.[17] We nod our heads in assent (how can we not!), when the Savior Himself tells us “great are the words of Isaiah” and gives “a commandment … that [we should] search these things diligently,[18] but resist giving the copious prophetic and doctrinal passages of scripture their full due.

Harold Bloom concludes that since the current “American Jesus can be described without any recourse to theology” we have become, on the whole, a post-Christian nation.[19] Others have characterized our national “faith in faith” as a “strange brew of devotion to religion and insouciance as to its content.”[20] Little wonder that the teaching of the central doctrines of the Gospel has been a significant focus of church leadership in our day.[21]

The historical divide. Once having gained confidence in our grasp of the plain sense of the words of scripture, we must still decode its pervasive imagery. Our problem with ancient imagery is that we live on the near side of a great divide that separates us from the religious, cultural, and philosophical perspectives of the ancients.[22] The Prophet Joseph Smith was far closer to this lost world than we are—not only because of his personal involvement with the recovery and revelatory expansion of ancient religion, but also because in his time many archaic traditions were still embedded in the language and daily experience of the surrounding culture.[23] Margaret Barker describes the challenges this situation presents to contemporary students of scripture:

Like the first Christians, we still pray “Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done in earth, as it is in heaven,”[24] but many of the complex system of symbols and stories that describe the Kingdom are no longer recognized for what they are.[25]

It used to be thought that putting the code into modern English would overcome the problem, and make everything clear to people who had no roots in a Christian community. This attempt has proved misguided, since so much of the code simply will not translate into modern English. … The task, then, has had to alter. The need now is not just for modern English, or modern thought forms, but for an explanation of the images and pictures in which the ideas of the Bible are expressed. These are specific to one culture, that of Israel and Judaism, and until they are fully understood in their original setting, little of what is done with the writings and ideas that came from that particular setting can be understood. Once we lose touch with the meaning of biblical imagery, we lose any way into the real meaning of the Bible. This has already begun to happen and a diluted “instant” Christianity has been offered as junk food for the mass market. The resultant malnutrition, even in churches, is all too obvious.[26]

The Special Challenges of the Old Testament

While the challenges outlined above apply to scripture reading in general, there are, in addition, special challenges that apply in particular to the Old Testament. Some of these challenges have been summarized by John Walton:[27]

Modern readers … may well be confused by obscure prophecies about people who no longer exist, obtuse laws that the New Testament identifies as obsolete, and graphic narratives of sex and violence that are simply disturbing when read in the context of that which is supposed to be God’s Word. Just how, we may ask, can the Old Testament possibly stand as God’s Word to us?

Walton answers this question as follows:[28]

Whether we are dealing with narratives, proverbs, prophecies, laws, or hymns, the forms and genres of the Old Testament are being employed for theological purposes. When historical events are being portrayed, theological perspectives offer the most important lens for interpretation. Events are not just reported by the authors; they are interpreted — and theology is the goal. When legal sayings are being collected, it is not the structure of society that is the focus, but insight on how Israel was to identify itself with the plans and purposes of Yahweh, its wise and holy covenant God. This literature, then, helped Israel to know how to live in His presence. … The theological nature of the text must have our primary attention.

Below, we will take the case of the Bible story of Creation as an illustration of why a doctrinal perspective on the Old Testament should always remain central to our efforts to appreciate and understand it, even while acknowledging the significant enrichment that historical, scientific, and textual studies can provide in a secondary role.

Figure 3. Michelangelo Buonarroti, 1475-1564:

Creation of Sun, Moon, and Planets, 1511

Creation as a case in point: Assumed vs. actual conflict between science and religion. The Creation account in the Bible has been a lightning rod of controversy for centuries among many Christians, including some Latter-day Saints.[29] Even today, many members of the Church believe that accepting scientific findings about Creation and the origin of man would amount to renouncing faith in the Bible as inspired scripture. However, Church leaders have taught that we need not read the Bible as an argument for “young earth creationism,” the idea that the earth was created over a period of several thousand years at most.[30] With respect to questions about the existence of animal life on earth before the Fall and evolution, current Church teachings are likewise clear.[31] For these questions, at least, scripture and science need not be seen as in conflict when both are well-understood.

More generally, Elder James E. Talmage taught in 1930 that “The opening chapters of Genesis and scriptures related thereto were never intended as a text-book of geology, archaeology, earth-science, or man-science.”[32] It is evident that Elder Talmage did not believe, as a well-respected geologist himself, that he was required to disavow the theories of science to embrace the claims of scripture. In doing so, scientifically-minded people of faith do not see themselves as subordinating the claims of faith to the program of science, but rather as attempting to circumscribe their understanding of truth — the results of learning by “study and also by faith”[33] — into “one great whole.”[34]

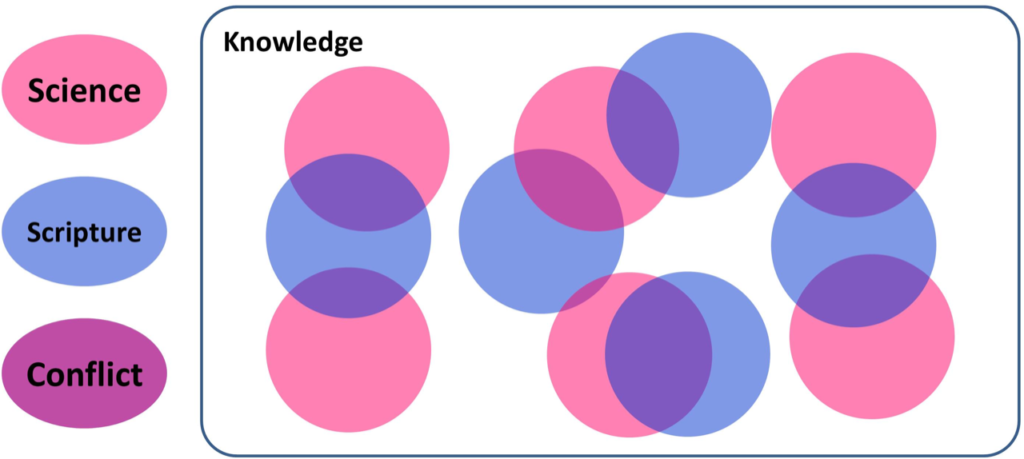

Figure 4. Assumed conflict between science and scripture.

With kind permission of Stephen T. Whitlock

Above is a simplified depiction that illustrates the relationship between science, scripture, and the domain of pertinent knowledge. Most of us are apt to think both that the ratio of our knowledge to our ignorance — the relative size and coverage of the circles in relationship to the rounded rectangle of overall knowledge — is greater than it probably is and also that the areas of conflict between science and scripture — the overlaps of the pink and blue circles — are larger and more numerous than they are likely to be in actuality.

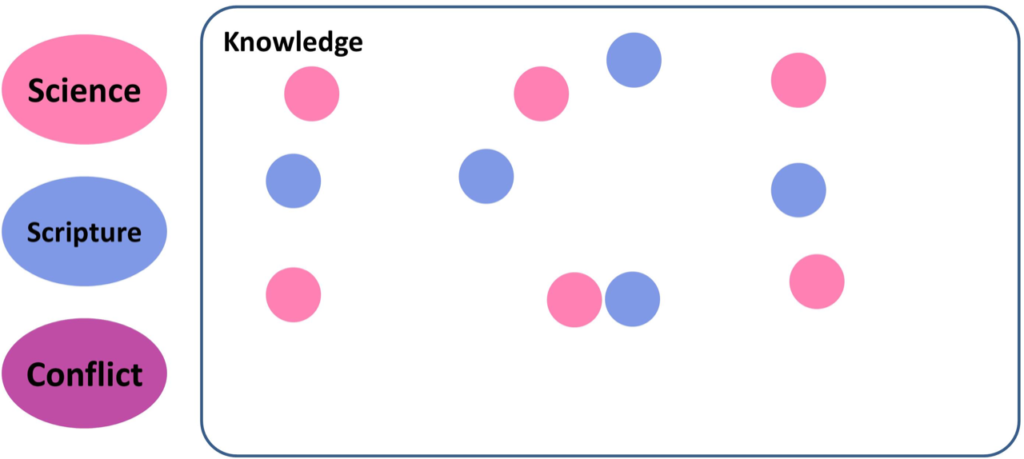

Figure 5. Actual conflict between science and scripture.

With kind permission of Stephen T. Whitlock

Fortunately, when we seriously explore areas of disagreement in just about any subject — rather than just assuming that we already know what those who disagree with us think — we usually learn that there were some aspects of the question about which we were quite ignorant (the pink circles cover much less of the overall space than we at first perceived). In addition, we may discover that the areas of actual disagreement are actually smaller and fewer than we had originally imagined. If we take the figure above to represent God’s view of things, our limited, life experience already provides the basis for the faith that when we finally see all things “as they really are”[35] there will be no conflict at all. Hence Elder Talmage’s dictum:[36]

Within the Gospel of Jesus Christ there is room and place for every truth thus far learned by man or yet to be made known.

Nephi taught the value of combining study and faith when he taught that “to be learned is good if they hearken unto the counsels of God.”[37] There is danger when one of these two approaches to learning predominates at the expense of the other. It has been said that when you only believe what you feel, you are a fanatic; when you only believe what you think, you are a skeptic; but the capacity both to think and to feel is required to receive revelation. As Elder Jeffrey R. Holland has stated: “truly rock-ribbed faith and uncompromised conviction comes with its most complete power when it engages our head as well as our heart.”[38]

That said, although my experience is that nearly all scientists and scholars are honorable and well-intentioned in their search for truth, they do not have the answers to life’s most important questions and most will readily admit that “the answers we have are merely provisional.”[39] For this reason, Holmes Rolston concluded: “The religion that is married to science today will be a widow tomorrow. … Religion that has too thoroughly accommodated to any science will soon be obsolete.”[40]

May I add that any religion that refuses dialogue with sincere scholarship also may be setting itself up for extinction. Elder Jeffrey R. Holland spoke to that point when he quoted the English cleric Austin Farrer:[41]

Though argument does not create conviction, lack of it destroys belief. What seems to be proved may not be embraced; but what no one shows the ability to defend is quickly abandoned. Rational argument does not create belief, but it maintains a climate in which belief may flourish.

Creation as a case in point: Science as a secondary consideration in scriptural understanding. I could have ended this article here, with a concluding statement of my belief that scripture and scholarship should not be seen as adversaries, and that, indeed, the study of each may be mutually enriching. However, I think there is a more important point to make — namely, that even if the scriptures that discuss Creation contributed absolutely nothing to the dialogue with science,[42] they would still merit serious study on other grounds. And those other grounds are of supreme importance: They teach us the doctrines of salvation and exaltation.

Scripture must be understood on its own terms, and not merely through the unconscious lens of our modern outlook.[43] In that respect, 2 Peter 1:20 reminds us that “no prophecy of the scripture is of any private interpretation,”[44] which I take as meaning, in part, that I am obligated to try to understand the divinely inspired expressions that have made their way (albeit imperfectly) to us through them. To consider the significance of scripture only with reference to the narrow, human interests of what they can tell us about science or history is to ignore what they were intended to accomplish. J. D. Pleins wisely observed that “Historical truth is a moving target, not a rock upon which to build faith. Faith, likewise, has its own work to do and cannot wait for the arrival of the latest issue of Near Eastern Archaeology before trying to sort things out.”[45]

For a time, I made this mistake with respect to the Creation scriptures. Having concluded that these passages were of little help to me in understanding how man and the universe came to be from a scientific perspective, I began to study them superficially, seeing their sole contribution as an ancient (though non-negligible) witness that God is our Maker.[46] Sadly, however, because I did not continue serious study of these chapters as significant in their own right, it took me years to realize that they were saturated with other, more important kinds of significance.

What I had failed to notice through my neglect is that the opening chapters of Genesis and the book of Moses seem to have been deliberately shaped to highlight resemblances between the creation of the universe and the architecture of the Tabernacle and later Israelite temples.[47] Understanding these parallels helps explain why, for example, in seeming contradiction to scientific understanding, the description of the creation of the sun and moon appears after, rather than before, the creation of light and of the earth.[48] The devoted study of many scholars has also made it evident that not only the Creation, but also the Garden of Eden provided a model for the architecture of the temple.

Because of this and other similar experiences, I have become more wary of what James L. Kugel has characterized as the “subtle shift in tone” that comes with “the emphasis on reading the Bible [solely] in human terms and in its historical context” without the counterbalance provided by traditional forms of scripture reading:[49]

As modern biblical scholarship gained momentum, studying the Bible itself was joined with, and eventually overshadowed by, studying the historical reality behind the text (including how the text itself came to be). In the process, learning from the Bible gradually turned into learning about it. Such a shift might seem slight at first, but ultimately it changed a great deal. The person who seeks to learn from the Bible is smaller than the text; he crouches at its feet, waiting for its instruction or insights. Learning about the text generates the opposite posture. The text moves from subject to object; it no longer speaks but is spoken about, analyzed, and acted upon. The insights are now all the reader’s, not the text’s, and anyone can see the results. This difference in tone, as much as any specific insight or theory, is what has created the great gap between the Bible of ancient interpreters and that of [many] modern scholars. …

What [modern exegetes] generally share (although there are, of course, exceptions) is a profound discomfort with the actual interpretations that the ancients came up with—these have little or no place in the way Scripture is to be expounded today. Midrash, allegory, typology — what for? But the style of interpretation thus being rejected is precisely the one that characterizes the numerous interpretations of Old Testament texts by Jesus, Paul, and others in the New Testament, as well as by the succeeding generations of the founders of Christianity. … Ancient interpretive methods may sometimes appear artificial, but this hardly means that abandoning them guarantees unbiased interpretation. … At times, [modern] interpretations are scarcely less forced than those of ancient midrashists (and usually far less clever).

The Why

This article has focused largely on why we should study the Old Testament. What about the “how”? Among the many things that could be said, I would like to stress a need for the personal qualities of humility and awe. The characteristic of awe — so vital to the pursuit of any knowledge through study and faith — was equated by Elder Neal A. Maxwell with the scriptural term “meekness.”[51] Illustrating this attitude of meekness with an anecdote about his scientist father, President Henry B. Eyring wrote:[52]

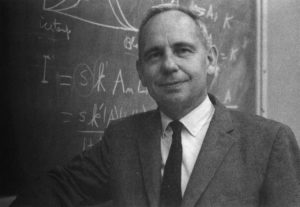

Figure 6. Henry Eyring (1901-1981) at the blackboard, 1958[50]

Some of you have heard me tell of being in a meeting in New York as my father presented a paper at the American Chemical Society. A younger chemist popped up from the audience, interrupted, and said: “Professor Eyring, I’ve heard you on the other side of this question.” Dad laughed and said, “Look, I’ve been on every side of it I can find, and I’ll have to keep trying other sides until I finally get it figured out.” And then he went on with his lecture. So much for looking as though you are always right. He was saying what any good little Mormon boy would say. It was not a personality trait of Henry Eyring. He was a practicing believer in the Lord Jesus Christ. He knew that the Savior was the only perfect chemist. That was the way Dad saw the world and his place in it. He saw himself as a child. He worked his heart out, as hard as he could work. He was willing to believe he didn’t know most things. He was willing to change any idea he’s ever had when he found something which seemed closer to the truth. And even when others praised his work, he always knew it was an approximation in the Lord’s eyes, and so he might come at the problem again, from another direction.

Some take the fact that scholarship reverses its positions from time to time as a disturbing thing. On the contrary, I feel that we should take such events as encouraging news. In this regard, I side with those who locate the rationality of science and scholarship not in the assertion that its theories are erected upon a consistent foundation of irrefutable facts but rather in the idea that it is at heart a self-correcting enterprise.[53] The payload of a mission to Mars precisely hits its landing spot not because we can set its initial course with pinpoint accuracy or because we can predict changing conditions along the way with any degree of reliability but rather because we can continue to adjust its trajectory as the rocket advances to its target. The same thing is true with religion — as Paul says, now we see only in part, now we know only in part[54] — that is why we need continuing revelation, and that is why we won’t understand some things completely until “the perfect day.”[55]

President Eyring’s father once said that it is the people who can tolerate “no contradictions in their minds [that] may have [the most] trouble.” As for himself, he continued: “There are all kinds of contradictions [in religion] I don’t understand, but I find the same kinds of contradictions in science, and I haven’t decided to apostatize from science. In the long run, the truth is its own most powerful advocate.”[56]

My gratitude for the love, support, and advice of Kathleen M. Bradshaw on this article. Thanks also to Mike Harris, Jonathon Riley, and Stephen T. Whitlock for valuable comments and suggestions.

Further Study

See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aXiVXmUBqn0 for a 15-minute excerpt from the 1960’s church film “The Search for Truth” posted on the Interpreter channel. It contains an opening statement by President David O. McKay on the value of science and the search for truth, followed by perspectives from prominent scientists, including Henry Eyring.

For other scripture resources relating to this lesson, see The Interpreter Foundation Old Testament Gospel Doctrine Index (https://interpreterfoundation.org/gospel-doctrine-resource-index/ot-gospel-doctrine-resource-index/) and the Book of Mormon Central Old Testament KnoWhy list (https://knowhy.bookofmormoncentral.org/tags/old-testament).

References

Alleman, John C. "Problems in translating the language of Joseph Smith." In Conference on the Language of the Mormons (May 31, 1973), edited by Harold S. Madsen and John L. Sorenson, 22-31. Provo, UT: Language Research Center, Brigham Young University, 1973.

Bailey, David H. "Science vs. religion: Can this marriage be saved?" In Science and Mormonism: Cosmos, Earth, and Man, edited by David H. Bailey, Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, John H. Lewis, Gregory L. Smith and Michael L. Stark. Interpreter Science and Mormonism Symposia 1, 13-39. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2016.

Bailey, David H., Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, John H. Lewis, Gregory L. Smith, and Michael L. Stark, eds. Science and Mormonism: Cosmos, Earth, and Man. Interpreter Science and Mormonism Symposia 1. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2016.

Ballard, M. Russell. 2016. The opportunities and responsibilities of CES teachers in the 21st century (Address to CES Religious Educators, CES Evening with a General Authority, 26 February 2016, Salt Lake Tabernacle). In LDS Broadcasts. https://churchofjesuschrist.org/broadcasts/article/evening-with-a-general-authority/2016/02/the-opportunities-and-responsibilities-of-ces-teachers-in-the-21st-century?lang=eng. (accessed March 19, 2016).

Barker, Margaret. On Earth as It Is in Heaven: Temple Symbolism in the New Testament. Edinburgh, Scotland: T&T Clark, 1995.

———. The Hidden Tradition of the Kingdom of God. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), 2007.

———. Christmas: The Original Story. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 2008.

Bateson, Gregory. Mind and Nature: A Necessary Unity. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1979.

Bateson, Gregory, and Mary Catherine Bateson. Angels Fear: Towards an Epistemology of the Sacred. New York City, NY: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1987.

Bednar, David A. 1998. "Teach them to understand". In BYU Broadcasting. https://www2.byui.edu/Presentations/transcripts/educationweek/1998_06_04_bednar.htm. (accessed December 18, 2011).

———. Increase in Learning: Spiritual Patterns for Obtaining Your Own Answers. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2011.

Bloom, Harold. Jesus and Yahweh: The Names Divine. New York City, NY: Riverhead Books (Penguin Group), 2005.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. "The tree of knowledge as the veil of the sanctuary." In Ascending the Mountain of the Lord: Temple, Praise, and Worship in the Old Testament, edited by David Rolph Seely, Jeffrey R. Chadwick and Matthew J. Grey. The 42nd Annual Brigham Young University Sidney B. Sperry Symposium (26 October, 2013), 49-65. Provo and Salt Lake City, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University and Deseret Book, 2013.

———. Creation, Fall, and the Story of Adam and Eve. 2014 Updated ed. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014.

———. "The LDS book of Enoch as the culminating story of a temple text." BYU Studies 53, no. 1 (2014): 39-73. http://www.templethemes.net/publications/140224-a-Bradshaw.pdf. (accessed September 19, 2017).

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. "Science and Genesis: A personal view." In Science and Mormonism: Cosmos, Earth, and Man, edited by David H. Bailey, Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, John H. Lewis, Gregory L. Smith and Michael L. Stark. Interpreter Science and Mormonism Symposia 1, 135-92. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2016.

———. "Foreword." In Name as Key-Word: Collected Essays on Onomastic Wordplay and the Temple in Mormon Scripture, edited by Matthew L. Bowen, ix-xliv. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2018.

Carr, Nicholas. 2008. Is Google making us stupid? (July/August 2008). In The Atlantic. http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2008/07/is-google-making-us-stupid/306868/. (accessed March 20, 2016).

———. The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains. New York City, NY: W. W. Norton, 2010.

———. "The juggler’s brain." The Phi Delta Kappan 92, no. 4 (December-January 2010-2011): 8-14. http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/27922479.pdf. (accessed March 20, 2016).

———. The Glass Cage: Automation and Us. New York City, NY: W. W. Norton, 2014.

Coles, Robert. The Secular Mind. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999.

Eco, Umberto. "Notes on referring as contract." In Kant and the Platypus: Essays on Language and Cognition, edited by Umberto Eco. Translated by Alastair McEwen, 280-336. Chicago, IL: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (Harvest), 2000.

Eyring, Henry. Reflections of a Scientist. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1983.

Eyring, Henry B. "Faith, authority, and scholarship." In On Becoming a Disciple-Scholar, edited by Henry B. Eyring, 59-71. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1995.

———. "The power of teaching doctrine." Ensign 29, May 1999, 73-75.

Fishbane, Michael. "A note on the spirituality of texts." In Etz Hayim Study Companion, edited by Jacob Blumenthal and Janet L. Liss, 11-12. New York City, NY: The Rabbinical Assembly, The United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism, and The Jewish Publication Society, 2005.

Fussell, Paul. 1983. Class: A Guide Through the American Status System. New York City, NY: Touchstone, 1992.

GIbb, Jocelyn, ed. Light on C.S. Lewis. San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace and Company/Harvest Book, 1965.

Hafen, Bruce C. Spiritually Anchored in Unsettled Times. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2009.

Harrison, B. Kent. "Truth, the sum of existence." In Of Heaven and Earth: Reconciling Scientific Thought with LDS Theology, edited by David L. Clark, 148-80. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1998.

Holland, Jeffrey R. 2017. The greatness of the evidence (Talk given at the Chiasmus Jubilee, Joseph Smith Building, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, 16 August 2017). In Mormon Newsroom. http://www.mormonnewsroom.org/article/transcript-elder-holland-speaks-book-of-mormon-chiasmus-conference-2017. (accessed August 18, 2017).

Hunter, Howard W. The Teachings of Howard W. Hunter. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1997.

Jensen, Marlin K. "Gospel doctrines: Anchors to our souls." Ensign 38, October 2008, 58-61.

King, Arthur Henry. 1992. "Joseph Smith as a Writer." In Arm the Children: Faith’s Response to a Violent World, edited by Daryl Hague, 285-93. Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 1998.

Knobel, Michele, and Colin Lankshear, eds. A New Literacies Sampler. New York City, NY: Peter Lang, 2007. http://everydayliteracies.net/files/NewLiteraciesSampler_2007.pdf. (accessed April 26, 2016).

Kugel, James L. How to Read the Bible: A Guide to Scripture, Then and Now. New York City, NY: Free Press, 2007.

LaCocque, André. The Trial of Innocence: Adam, Eve, and the Yahwist. Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2006.

Lasch, Christopher. 1995. The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy. New York City, NY: W. W. Norton, 1996.

Lewis, C. S. 1955. "’De Descriptione Temporum’." In Selected Literary Essays, edited by Walter Hooper, 1-14. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1969.

Lynch, Michael Patrick. 2016. Teaching in the time of Google. In The Chronicle of Higher Education. http://chronicle.com/article/Teaching-in-the-Time-of-Google/236180. (accessed April 26, 2016).

Mander, Jerry, and W. David Kubiak. Nancho consults Jerry Mander. In The Nancho Consultations. http://www.nancho.net/advisors/mander.html. (accessed March 20, 2016).

Mander, Jerry. Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television. New York City, New York: HaperCollins, 1978.

Maxwell, Neal A. "The disciple-scholar." In On Becoming a Disciple-Scholar, edited by Henry B. Eyring, 1-22. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1995.

McConkie, Bruce R. "Christ and the creation." Ensign 12, June 1982, 8-15.

McGuire, Benjamin L. "Nephi and Goliath: A case study of literary allustion in the Book of Mormon." Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 18, no. 1 (2009): 16-31. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1535&context=jbms. (accessed March 19, 2016).

———. "Email message to Jeffrey M. Bradshaw." March 7, 2016.

Nadauld, Stephen D. Principles of Priesthood Leadership. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1999.

Numbers, Ronald L. The Creationists: The Evolution of Scientific Creationism. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1992.

Packard, Dennis, and Sandra Packard. Feasting Upon the Word. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1981.

Packer, Boyd K. "Principles (abridged from a talk given at a Regional Representatives Seminar, 6 April 1984)." Ensign 15, March 1985, 6-10.

———. "Little Children." Ensign 16, November 1986, 16-18.

———. "The great plan of happiness." Presented at the Seventeenth Annual Church Educational System Religious Educators’ Symposium on the Doctrine and Covenants/Church History, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, August 10, 1993, 1-7. http://ldsces.org/general%20authority%20talks/bkp.The%20Great%20Plan%20of%20Happiness.1993.pdf. (accessed August 24, 2008).

———. "Do not fear." Ensign 34, May 2004, 77-80.

———. Mine Errand from the Lord: Selections from the Sermons and Writings of Boyd K. Packer. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2008.

Pleins, J. David. When the Great Abyss Opened: Classic and Contemporary Readings of Noah’s Flood. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Prothero, Stephen. Religious Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know—and Doesn’t. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, 2007.

Rackley, Eric D. E-mail message to Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, April 25, 2016.

———. "Latter-day Saint youths’ construction of sacred texts." Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 19 (2016): 39-65. http://cdn.interpreterfoundation.org/jnlpdf/rackley-v19-2016-pp39-65-PDF.pdf. (accessed April 26, 2016).

Radebaugh, Jani. "The outer solar system: A window to the creative breadth of divinity." In Science and Mormonism: Cosmos, Earth, and Man, edited by David H. Bailey, Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, John H. Lewis, Gregory L. Smith and Michael L. Stark. Interpreter Science and Mormonism Symposia 1, 299-314. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2016.

Rich, Motoko. 2008. Literacy debate: Online, R U really reading? (27 July 2008). In The New York Times, Books. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/27/books/27reading.html. (accessed March 30, 2016).

Rolston, Holmes, III. 1987. Science and Religion: A Critical Sruvey. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2006.

Romeo, Nick. 2015. Is Google making students stupid. In The Atlantic (30 September 2014). http://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2014/09/is-google-making-students-stupid/380944/. (accessed March 20, 2016).

Santillana, Giorgio de, and Hertha von Dechend. 1969. Hamlet’s Mill: An Essay on Myth and the Frame of Time. Boston, MA: David R. Godine, 1977.

Seaich, John Eugene. Ancient Texts and Mormonism: Discovering the Roots of the Eternal Gospel in Ancient Israel and the Primitive Church. 2nd Revised and Enlarged ed. Salt Lake City, UT: n. p., 1995.

Smith, Joseph, Jr. Scriptural Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, ed. Richard C. Galbraith. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1993.

———. 1938. Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1969.

Smith, Mark S. The Priestly Vision of Genesis 1. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2010.

Talmage, James E. 1931. "The earth and man (originally published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Deseret News, November 21, 1931, pp. 7-8)." In Science and Mormonism: Cosmos, Earth, and Man, edited by David H. Bailey, Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, John H. Lewis, Gregory L. Smith and Michael L. Stark. Interpreter Science and Mormonism Symposia 1, 335-51. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2016. https://archive.org/details/CosmosEarthAndManscienceAndMormonism1. (accessed 1 April 2018).

Tullidge, Edward W. 1877. The Women of Mormondom. New York City, NY: n.p., 1997.

Valéry, Paul. 1937. "Our destiny and literature." In Reflections on the World Today. Translated by Francis Scarfe, 131-55. New York City, NY: Pantheon Books, 1948.

Vincent, M. R. Word Studies in the New Testament. New York City, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1887.

Viola, Frank, and George Barna. 2002. Pagan Christianity? Exploring the Roots of Our Church Practices. Revised and updated ed. Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale House, 2008.

Walton, John H. Old Testament Theology for Christians: From Ancient Context to Enduring Belief. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2017.

Weimer, W. Notes on the Methodology of Scientific Research. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Erlbaum, 1979.

What does the Church belive about dinosaurs? (February 2016). In New Era. https://churchofjesuschrist.org/new-era/2016/02/to-the-point/what-does-the-church-believe-about-dinosaurs?lang=eng. (accessed April 21, 2018).

What does the Church belive about evolution? (October 2016). In New Era. https://churchofjesuschrist.org/new-era/2016/10/to-the-point/what-does-the-church-believe-about-evolution?lang=eng. (accessed April 21, 2018).

Young, Brigham. 1876. "Personal revelation the basis of personal knowledge; philosophic view of Creation; apostasy involves disorganization and returns to primitive element; one man power (Discourse by Brigham Young, delivered in the New Tabernacle, Salt Lake City, Sunday Afternoon, September 17, 1876)." In Journal of Discourses. 26 vols. Vol. 18, 230-35. Liverpool and London, England: Latter-day Saints Book Depot, 1853-1886. Reprint, Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1966.

Endnotes

Clearly, reading in print and on the Internet are different. On paper, text has a predetermined beginning, middle and end, where readers focus for a sustained period on one author’s vision. On the Internet, readers skate through cyberspace at will and, in effect, compose their own beginnings, middles and ends. …

Critics of reading on the Internet say they see no evidence that increased Web activity improves reading achievement. “What we are losing in this country and presumably around the world is the sustained, focused, linear attention developed by reading,” said Mr. Gioia of the N.E.A. “I would believe people who tell me that the Internet develops reading if I did not see such a universal decline in reading ability and reading comprehension on virtually all tests.”

Nicholas Carr sounded a similar note in “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” in the current issue of the Atlantic magazine (N. Carr, Is Google. See also, e.g., N. Carr, Shallows; N. Carr, Glass Cage; N. Carr, Juggler’s Brain; N. Romeo, Is Google). Warning that the Web was changing the way he — and others — think, he suggested that the effects of Internet reading extended beyond the falling test scores of adolescence. “What the Net seems to be doing is chipping away my capacity for concentration and contemplation,” he wrote, confessing that he now found it difficult to read long books. …

Neurological studies show that learning to read changes the brain’s circuitry. Scientists speculate that reading on the Internet may also affect the brain’s hard wiring in a way that is different from book reading.

“The question is, does it change your brain in some beneficial way?” said Guinevere F. Eden, director of the Center for the Study of Learning at Georgetown University. “The brain is malleable and adapts to its environment. Whatever the pressures are on us to succeed, our brain will try and deal with it.”

Some scientists worry that the fractured experience typical of the Internet could rob developing readers of crucial skills. “Reading a book, and taking the time to ruminate and make inferences and engage the imaginational processing, is more cognitively enriching, without doubt, than the short little bits that you might get if you’re into the 30-second digital mode,” said Ken Pugh, a cognitive neuroscientist at Yale who has studied brain scans of children reading.

Eric Rackley takes issue with some of the views summarized by Rich, and proffers a more hopeful view based on efforts to gain a better understanding of what motivates youth to read in the first place (E. D. Rackley, April 25 2016):

[P]urpose matters. And motivation too. Show me a youth who can’t read scripture for more than two minutes and I’ll give her something to read that’s important to her and probably pretty complex and we’ll sit back and watch her read for hours. … [Those who say that reading ability and comprehension are declining are mistaken.] Adolescents’ reading comprehension as measured by the National Assessment of Educational Progress shows that youths’ reading abilities have actually improved a little since 1992 (http://www.nationsreportcard.gov/). More pressing issues include the reading gap between white and black students, and the relatively stable 2/3 of students who don’t read proficiently. The NEAP data suggest that reading skill isn’t declining, it’s just not increasing as quickly as it could and for all of our young people equally. … A digital text can be as enriching as any other text or as mind-numbing. The issue may not be the nature of the texts, but how we engage with them. Pugh talks about “taking the time to ruminate and make inferences and engage the imaginational processing.” That happens with digital texts. It’s not isolated to books. For me, teaching youth is the key. We must teach them how to do what Pugh suggest with any text, even the boring and complex ones. We must also give them opportunities to practice doing this with various kinds of text for a variety of purposes. One of the affordances of nonlinear digital texts is that they give readers a chance to develop different parts of their “reading” brains.

Consistent with Rackley’s views, M. P. Lynch, Teaching asks whether higher education will become obsolete in the face of ubiquitous, immediate access to the world’s knowledge through technology. He points out what makes what he calls “Google knowing” both useful and problematic: “The Internet is at one and the same time the most glorious fact-checker and the most effective bias-affirmer ever invented.” Because of the “epistemic overconfidence that Google knowing encourages,” “teaching critical, reflective thinking matters more than ever.” Critical thinking, he argues, is one means to achieve one of the enduring ideals of higher education, namely, helping people “gain understanding,” “to comprehend hidden relationships among different pieces of understanding” through facilitating “the creative abilities that understanding requires.”

Although concerns about differences between reading on paper and reading from a screen are probably overdone, there is no doubt that, in general, different media exploit different sensory and cognitive strengths and weaknesses. Already in 1937, the prescient Paul Valéry ruminated on the various consequences of “broadcasting and the gramophone” on literature (P. Valéry, Our Destiny, pp. 148-150, 152. See also J. Mander, Four Arguments; J. Mander et al., Nancho Consults Jerry Mander):

We can already begin wondering whether a purely spoken and auditive literature will not fairly soon replace written literature. That would be a return to the most primitive times, and the technical consequences would be immense. What would happen if writing died out? First of all — and this would be an advantage — the voice and the needs of the ear would regain, in matters of form, the capital importance which whose conditions of the senses had until a few hundred years ago. Immediately, the structure and dimensions of literary works would be strongly affected; but the author’s work would be much less easy to reconsider. Certain poets would no longer be able to remain so complicated as they are made out to be, and readers, transformed into listeners, would hardly be able to return to a passage, read it over, go more deeply into it through enjoyment or criticism as they can do with a text they can hold in their hands.

There is another point. Suppose television develops (and I admit I do not welcome it), then immediately the entire descriptive parts of works could be replaced by visual representation; landscapes and portraits would no longer be the province of men of letters, and they would elude the means of language. One can go further. The sentimental parts would also be reduced, if not entirely abolished, thanks to the intervention of tender pictures and appropriate music released at the psychological moment. …

And there is, finally, another possible and perhaps more serious consequence of the introduction of all these new methods: What happens to abstract literature? So long as it is a question of amusing, touching, or seducing men’s minds one might agree, at a pinch, that broadcasting would be adequate. But science and philosophy demand quite another rhythm of thought than reading aloud could allow, or rather, they impose an absence of rhythm. Reflection stops or breaks its impulsion every second, it introduces uneven tempos, returns, and detours which demand the physical presence of a text and the possibility of handling it at leisure. All this is cut out by audition. Listening is inadequate for the transmission of abstract works. …

But all this is rather clumsily derived from our present physical potentialities. We must go a little farther. To think of the destiny of letters is to think at the same time and above all of the destiny of the mind. At this point everyone is at a loss. We can only too freely imagine this future as we wish, and we can arbitrarily suppose either that things will continue to be fairly like those we know, or that in the age to come there will be a depression of intellectual values, a lowering or decadence comparable to what happened at the close of classical antiquity; culture almost abandoned, works becoming incomprehensible and being destroyed, production abolished, all of which is unfortunately quite possible and even possible by two methods we already know: either through the use of powerful weapons of destruction, decimating the populations of the most cultured regions of the globe, ruining monuments, libraries, laboratories, and archives, and reducing the survivors to a misery exceeding their intelligence and suppressing all the elevates the mind of man; or else that not these means of destruction but those of possession and enjoyment, the incoherence imposed by the frequency and facility of impressions, the rapid vulgarization and application of industrial techniques to the productions, evaluations, and consumption of the mind’s fruits, will end in impairing the highest and most important intellectual virtues — concentration, meditative and critical powers, and what one may call thought in the grand style, thorough research directed towards the most exact and most powerful expression of its object.

We are living under the perpetual régime of intellectual disturbance. Intensity and novelty have in our time become good qualities, which is a rather remarkable symptom. I cannot believe that this system is good for culture. Its first result will be to make unintelligible or insupportable all the works of the past which were composed in quite different conditions and which were meant for minds that were formed entirely differently.

… a disease of the spirit that can lead us to imagine that we already know what we are reading, causing us to blithely and triumphantly read past the text… The spiritual task of interpretation … is to affect or alter the pace of reading so that one’s eye and ear can be addressed by the text’s words and sounds — and thus reveal an expanded or new sense of life and its dynamics. The pace of technology and the patterns of modernity pervert this vital task. The rhythm of reading must, therefore, be restored to the rhythm of breathing, to the cadence of the cantillation marks of the sacred text. Only then will the individual absorb the texts with his or her life breath and begin to read liturgically, as a rite of passage to a different level of meaning. And only then may the contemporary idolization of technique and information be transformed, and the sacred text restored as a living teaching and instruction, for the constant renewal of the self.

Ironically, of all Joseph Smith’s great accomplishments in the work of the Restoration, the one perhaps least appreciated was his immense knowledge of the scriptures. The scriptures were the brick and mortar of all his sermons, writings, and other personal communications; he quoted them, he alluded to them, he adapted them in all his speaking and writing.

The Prophet’s extensive use of the scriptures may not be obvious to the casual reader. In the book Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, for example, the Prophet appears to cite fewer than one passage of scripture every other page. … But that figure misses the mark. A more careful reading of this book reveals some twenty scriptures for every one actually cited. When I discovered that, I began to ask, not “When is the Prophet quoting scripture,” but rather “What might he be quoting that is not scripture?”

Of course, as Ben McGuire observes, we have to be cautious when we draw parallels using a computer-aided search (B. L. McGuire, March 7 2016):

Finding scriptural phrases in a text is not the same thing as finding scriptural citations. A citation is an intentional movement of text, and computer algorithms are, for the most part, not capable of distinguishing between such an intentional borrowing and coincidental usage or echoes. This is particularly true in the time of Joseph Smith, where the King James Bible was arguably the most influential literary work available. And because of this, the use of King James language cannot be automatically considered to be a citation of the biblical text. I am not sure that this needs much clarification in the chapter, but it is a problematic issue. The problem is that it tends to create an opposite swing (and perhaps one just as great) as the original identified problem. If we weren’t identifying all of the citations before, we may be identifying too many now. And reading allusion where none was intended may well provide us with deep insight, it certainly doesn’t represent the message intended by the author (Joseph Smith in this case). At best computer assisted search only helps us identify potential citations which then need to be eyeballed by a human being with a solid method.

With respect to scriptural allusions by Joseph Smith, Alleman concludes that “quoting from the Bible came as naturally to [the Prophet] as speaking itself.” However he notes that the occurrence of scriptures in the writings of Joseph Smith can be a problem for translators because “frequently, whether intentionally, or by oversight, the quotation differs from the original. The example … shows an extreme case in which eight different passages are worded into a single sentence. Some are quoted accurately but others are not. In one case … the difference is so great that one cannot really speak of a quotation; rather we give the translator a reference to the scripture which contains similar words, so that he can have a source for selecting the vocabulary items he will use, but he will have to put them into a completely different structure to translate the sense of the original” (J. C. Alleman, Problems in translating the language of Joseph Smith, p. 26).

… preached therapy more than theology, happiness rather than salvation. Then, as today, debating (or even discussing) religious doctrines was considered ill-mannered, a violation of the cherished civic ideal of tolerance, so it was difficult for children to learn or for adults to articulate what set their religious traditions apart from others.

Current interest in contemplative practice has caused “spiritual but not religious” folks to rediscover such neglected resources inside Christianity and Judaism as centering prayer and Kabbalah. But it has also led them to Buddhism, Hinduism, Taoism, and other Asian religions in search of various forms of meditation, yoga, and tai chi… Here too, however, the trend is toward religion stripped down to its “essentials”—essentials that in this case are confined almost entirely to the experiential or moral dimensions. This development is well advanced in the American Buddhist community, where some have argued that Buddhism can get along just fine without such staples as karma and reincarnation. “Buddhism Without Beliefs,” as this movement has been called, aims to distill the Buddhist life down to nothing more than one’s favorite sitting or chanting practice, and then to put that practice at the service of such American preoccupations as happiness. The tendency to shirk from doctrine is particularly pronounced in the “multi-religious America” camp. Here even the minimal monotheism of the Judeo-Christian-Islamic model must be sacrificed since many Buddhists don’t believe in God and many Hindus believe in more than one. The only common ground here seems to be tolerance itself. When pluralists gather for interreligious dialogue, their discussions always seem to circle back to ethics… [without] a whisper of theology.

Eric Rackley’s pioneering study on how “Latter-day Saint youths’ social and cultural values, practices, beliefs, and experiences influence their views of scripture” is a good example of how empirical research can be helpful in future efforts to develop “more effective religious literacy practices that are more responsive to youths’ histories with scripture” (E. D. Rackley, Latter-day Saint Youths’ Construction, p. 41).

For more on the meaning and implications of this verse, see J. M. Bradshaw, Foreword, pp. xiv, xl-xlii.

Some disagreements [between science and religion] are inevitable because our knowledge is incomplete. But we believe in a unified truth and so we eventually expect agreement. It is tempting to seek agreement now. However, it is inappropriate, and often dangerous, to attempt a premature reconciliation or conflicting ideas where there is a lack of complete knowledge. If a scientist concludes that there is no God — based on inadequate evidence! — and thereby casts doubt on those who believe in God, he does them a disservice. For example, it is inappropriate for a scientist who accepts organic evolution to claim that there is no God. (However, many scientists do indeed take the position that they cannot comment on religious truth because they have little or no information on it.)

Similarly, if an ecclesiastic states that such and such a scientific idea is not true — based on inadequate evidence! — then he does a disservice to the scientist who has carefully explored that idea. As a hypothetical example, it would be inappropriate for a church authority to make a flat statement that special relativity is invalid because it limits information transmission such as prayer to the very slow (!) speed of electromagnetic waves. It may later turn out to be invalid in some sense, but current experimental and other considerations support it strongly.

The proper stance, it seems, is to withhold judgment on such questions until we have more information — but also to take advantage of what knowledge we do have.

face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.”