An Old Testament KnoWhy[1]

Gospel Doctrine Lesson 14:

“Ye Shall Be a Peculiar Treasure Unto Me”

(Exodus 15-20; 32-34) (JBOTL14B)

Figure 1. Nicolas Poussin, 1594-1665: The Adoration of the Golden Calf, 1634-1635.

Question: The making of the golden calf is often presented as the height of Israel’s rejection of God and His law. But it was only one of several incidents of rebellion that occurred in the wilderness. Among all these provocations, which ones were the most serious?

Summary: The translations, revelations, and teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith make it clear that the most serious provocations of Israel had nothing to do with their frequent complainings in the wilderness, as one might otherwise imagine. Rather, they had to do with Israel’s deliberate rejection of “the last law from Moses,”[2] a law associated with the fulness of the priesthood and its blessings. In their rejection of that law, Israel had refused “to sanctify [themselves] that they might behold the face of God”[3] at Sinai. Instead, they prayed “that God would speak to Moses and not to them.”[4] “In consequence of [their actions, God] cursed them with a carnal law.”[5] And, as a result of their actions, the generation of Israelites who left Egypt in the Exodus would neither enter into the promised land[6] nor into “the rest of the Lord”[7] during their mortal lives. Happily, the Lord holds out the possibility of receiving these sometimes-rejected blessings to faithful disciples in our day who are willing to make and keep the covenants that will enable them to continually enjoy the divine presence. Through “sufficient hope,”[8] the “peaceable followers of Christ”[9] may “enter into the rest of the Lord”[10] in this life, “until [they] shall rest with him in heaven.”[11] This rest “is the fulness of his glory.”[12]

The Know

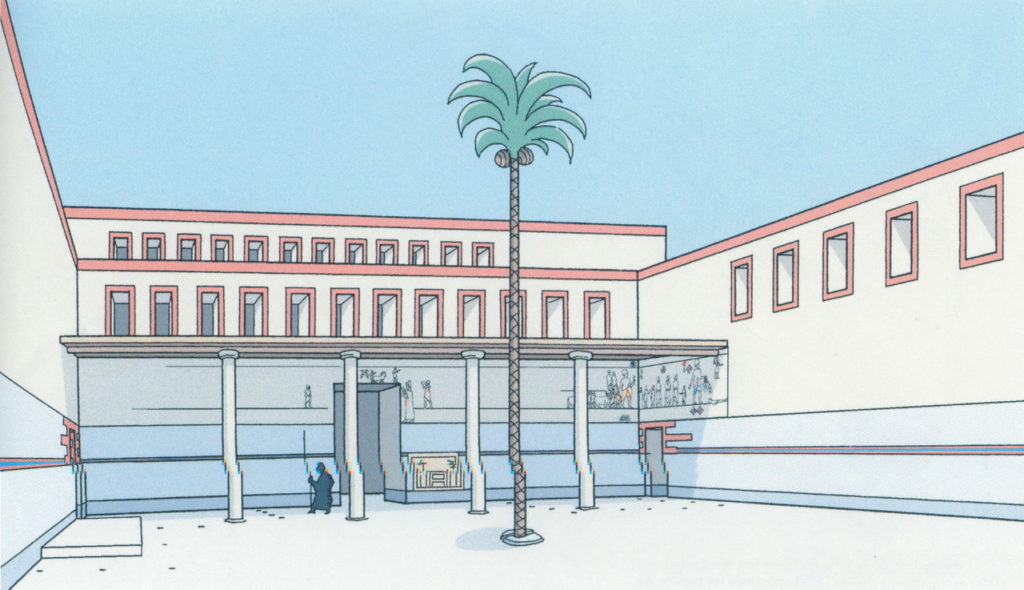

Temple Ordinances Sometimes Administered in Partial Form

Figure 2. The Court of the Palm at the Old Babylonian Palace of Mari, ca. 1800 BCE.[13] A tree, either real or artificial, took the central position in the palace courtyard through which the king would pass as part of rites of royal investiture. Sometime prior to passing through this area, he would have heard the recital of an account of the Creation. The placement of the tree recalls the biblical account of the tree “in the midst”[14] (literally “in the center”) of the Garden of Eden. Wooden posts, crafted to represent a second type of tree, supported a woven partition. The king would eventually pass through this partition to enter into the presence of the gods.[15]

Joseph Smith taught that temple ordinances had been available in their fulness to select individuals and families since the time of Adam and Eve.[16] However, they often have been administered only in a partial form due to the unreadiness of the covenant people to receive more.[17] In times of apostasy, the temple ordinances associated with the higher or Melchizedek Priesthood were almost totally withdrawn from the earth. Intriguingly, Jewish sources allude to things pertaining to Solomon’s Temple that were no longer present in the Second Temple.[18]

The translations, revelations, and teachings of the Prophet are clear in their witness that earlier forms of such loss also occurred in Moses’ day. At first, the Lord expressed His intent to make the higher ordinances of the holy priesthood available to all of Israel.[19] However, because of their rebellion, the higher priesthood and its associated laws and ordinances were instead generally withheld from the people.[20] Consistent with the teachings of Joseph Smith, President Brigham Young stated:[21]

If they had been sanctified and holy, the children of Israel would not have traveled one year with Moses before they would have received their endowments and the Melchizedek Priesthood. But they could not receive them, and never did. … The Lord told Moses that he would show Himself to the people, but they begged Moses to plead with the Lord not to do so.

Some prophets and kings, however, did continue to receive the highest ordinances of the Melchizedek priesthood in later Old Testament times.[22] The overall structure and many of the details of kingship rites in Israel can be found in the Bible, and analogous rituals were practiced elsewhere in the ancient Near East and in Egyptian tradition.[23] Portions were imperfectly preserved in the teachings and rituals of some strands of second temple Judaism, in the practices of Copts and of Christians with Gnostic leanings, and in the liturgies of Christian Churches.[24] Later, Christians with antiquarian interests incorporated and further developed selected aspects of ancient rituals as early Freemasonry took shape.[25] But although many of these individuals and movements held worthy ideals and intentions, because they lacked the “authority” of the “greater priesthood” that enables the “power of godliness” to be “manifest[ed]” through its “ordinances,”[26] these rites could be no more than a shadow of what God originally had in store for His covenant people.

By way of contrast to unauthorized and imperfectly preserved temple rites, the rites performed by Aaronic priests, though not incorporating the ordinances pertaining to the higher priesthood, were performed in a manner that was acceptable to the Lord. Before continuing with a discussion of how and what temple privileges were partially withdrawn from the Israelite priesthood — and completely withdrawn from the children of Israel generally — it will be helpful to understand how the Tabernacle functioned as a model of God’s holy mountain in Eden and at Sinai.

The Tabernacle as a Model of God’s Holy Mountain

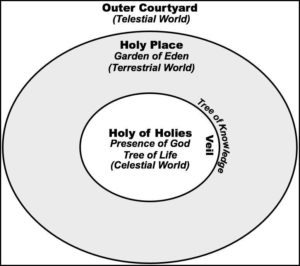

Figure 3. Zones of Sacredness in the Garden of Eden and in the Temple[27]

Although Latter-day Saints are familiar with the mountain as a symbol of the temple (e.g., Isaiah 2:2: “the mountain of the Lord’s house”), many may not realize how deeply this theme is interwoven in the scriptures from Genesis onward.

Biblical scholarship has increasingly come to see the Garden of Eden as a temple prototype,[28] consistent with many earlier Jewish and Christian traditions. For example, Ephrem the Syrian, a fourth-century Christian, pictured Paradise as a great mountain with the tree of knowledge providing a permeable, circular boundary partway up the slopes. The tree of knowledge, Ephrem concluded, “acts as a sanctuary curtain [i.e., veil] hiding the Holy of Holies, which is the Tree of Life higher up.”[29] In addition to this inner boundary, Jewish, Christian, and Muslim sources sometimes speak of a “wall” surrounding the whole of the garden, separating it from the “outer courtyard” of the mortal world.[30]

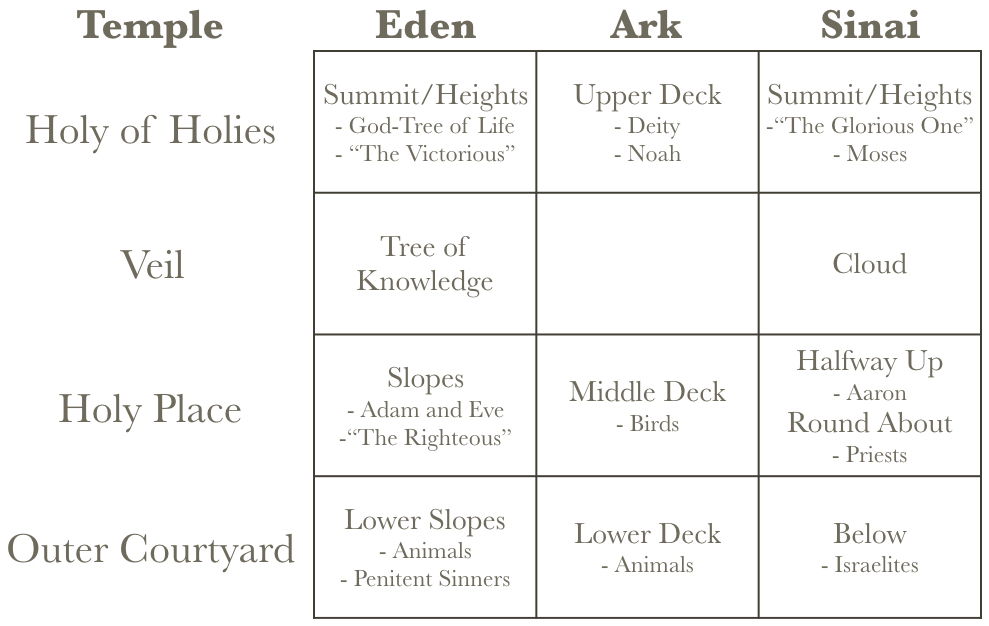

Figure 4. Ephrem the Syrian’s Comparison of the Layout of Eden, Noah’s Ark, and Mount Sinai

In explaining his conception of Eden, Ephrem cited parallels with the division of the animals on Noah’s ark and the demarcations on Sinai separating Moses, Aaron, the priests, and the people.[31] According to this way of thinking, movement inward toward the sacred center was symbolically equivalent to moving upward toward the top of the sacred mountain.

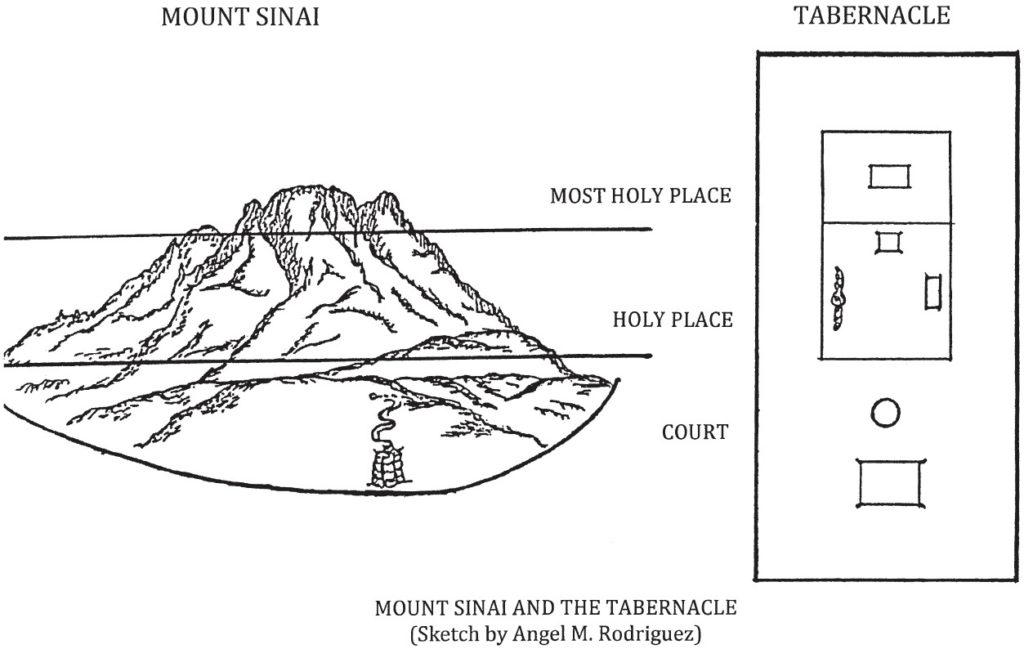

Figure 5. Correspondence Between Mount Sinai and the Layout of the Tabernacle[32]

Recall that on Sinai, Israel was gathered in three groups: “the masses at the foot of the mountain, where they viewed God’s ‘Presence’ from afar; the Seventy part way up; and Moses at the very top, where he entered directly into God’s Presence,”[33] having received his full endowment.[34] Likewise, Ephrem described the “lower, second, and third stories”[35] of the temple-like Ark so as to highlight the righteousness of Noah and to distinguish him from the “animals” and the “birds.”[36] Finally, as explained previously, Ephrem pictured Eden similarly as a great mountain, with the Tree of Knowledge providing a boundary partway up the slopes.

Seen from this perspective, the Tabernacle was a model of God’s Holy Mountain.[37] Within the Tabernacle, the high priest was able to come into the presence of the Lord ritually. On Mount Sinai, Moses was able to come into the presence of the Lord in actuality. Understanding this model helps us make sense of Israel’s most serious provocations and their consequences.

Israel’s Provocations in the Wilderness

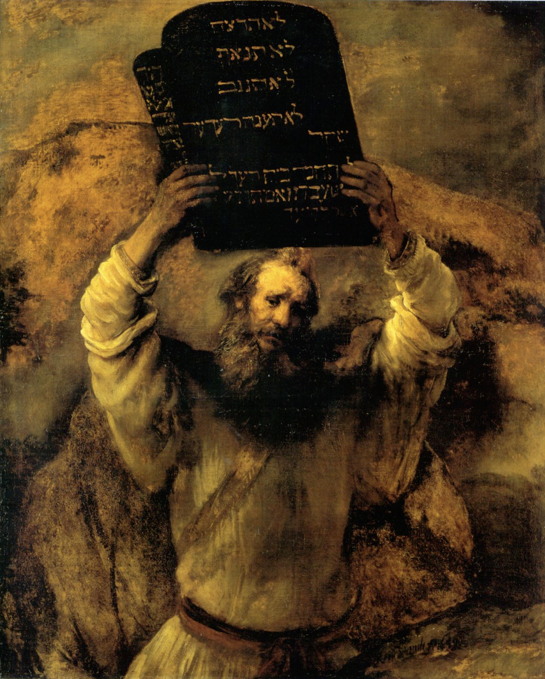

Figure 6. Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, 1606-1669:

Moses and the Tablets of the Law

In Numbers 14:22, the Lord told Moses why He would not allow the children of Israel who were part of the first generation of the Exodus into the promised land:

Because all those men which have seen my glory, and my miracles, which I did in Egypt and in the wilderness, and have tempted[38] me now these ten times, and have not hearkened to my voice.

Although students of the Bible have produced various lists of the “ten” provocations mentioned in this verse, it is more likely that the number ten is “a round figure, emphasizing complete testing.”[39] In other words, the Lord is saying that the provocations of the children of Israel have tested him to the limit.

BYU Professor M. Catherine Thomas has summarized the three most serious provocations:[40]

- First, at the foot of Sinai, where the Lord tried to sanctify His people and to cause them to come up the mountain, enter His presence, and behold His face, the Israelites refused to exercise sufficient faith to overcome their fear and enter into the fire, smoke, and earthquake that lay between them and the face of God. They said to Moses, “Speak thou with us, and we will hear: but let not God speak with us, lest we die.”[41] Moses responded, “Fear not.”[42] Nevertheless, “the people stood afar off, and Moses drew [alone] near unto the thick darkness where God was.”[43]

- Second, when the Israelites were camped at Kadesh Barnea in the wilderness, the Lord tried to bring them into the promised land, but they were so frightened by the report of giants in the land that neither Moses nor Caleb and Joshua could get them to exercise enough faith to enter and conquer the land.[44] Again, as at Massah and Meribah, they refused the grace of the Lord.

- Third, again at Sinai, when Moses went up to receive the fulness of the Gospel from the Lord on the first set of plates, the Israelites made and set up the golden calf. Their rejection of the Lord in the very moment that Moses was receiving the fulness of the Gospel for them was a most serious provocation. When he discovered what they had done, Moses broke the tables before the children of Israel. A second, lesser set of plates was made, but they were missing “the words of the everlasting covenant of the holy priesthood,”[45] meaning the higher, sanctifying ordinances of the Melchizedek Priesthood. Those were the very ordinances that gave access to the presence of the Lord.[46]

Note that these three provocations are interrelated. In the first, Israel refused to come into the presence of God. In the second, they refused to enter the promised land. And in the third, they refused to accept God’s “last law.”[47] In each case, they were willing to go thus far and no farther. Finally, in a sort of “three-strikes-your-out” fashion, the people had fully disqualified themselves for the enjoyment of God’s personal presence — a blessing for which Moses had “sought diligently”[48] to prepare them. The people had chosen to stand “afar off”[49] from the Lord and in the end they were granted just what they wanted — distance from the divine presence at Sinai, distance from the divine presence in the Tabernacle.

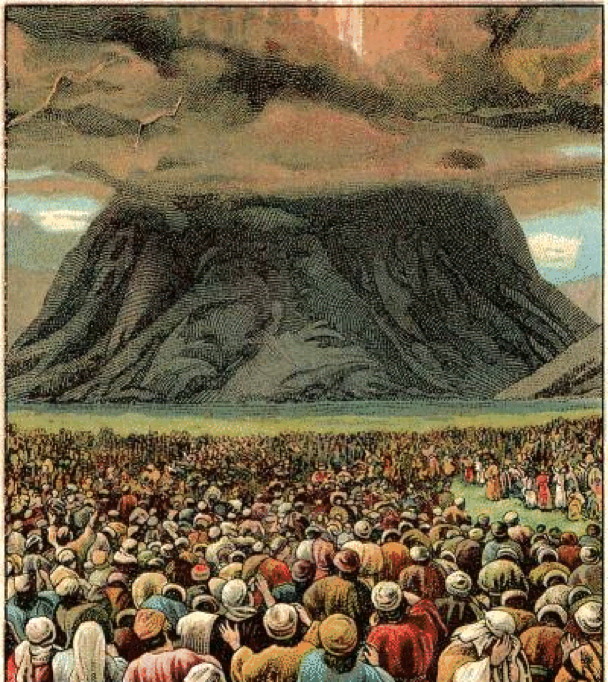

Figure 7. The Children of Israel at Mount Sinai.

Painting a vivid word picture of the Israelites’ inability to stand in the presence of the Lord, the medieval Jewish commentator Rashi explained that when the people heard the sound of the voice of God emanate from Sinai “they moved backwards and stood at a distance: they were repelled to the rear a distance of twelve miles — that is the whole length of the camp. Then the angels came and helped them forward again.” Avivah Zornberg reasons: “If this happened at each of the Ten Commandments, the people are imagined as traveling 240 miles in order to stand in place!”[50] Though Rashi’s imagery is, of course, only figurative, it is highly instructive.

We see a similar, movement away from eternal life and toward the regions of spiritual death at the incident of the Golden Calf.[51] Before their sin, the Israelites looked without fear upon the divine flames of God’s presence at the top of the mountain, but, as soon as they had sinned, they could not bear to see even the face of Moses, God’s intermediary.[52] By way of contrast to the Israelites, Moses, like Jesus at the Transfiguration,[53] was covered by a glorious cloud[54] as he communed face-to-face with the Lord, having been made like God Himself.[55] Moses then stood to Israel as God stood to him and, having received the power of an eternal life, he became known in the Samaritan literature as “the Standing One.”[56]

Figure 8. Harry Anderson, 1906-1996: Moses Calls Aaron to the Ministry[57]

Varying Distances from the Lord in Tabernacle Service

Varying distances from the Lord’s presence in Tabernacle service are made vivid in this painting by Harry Anderson. Moses, who stands, according to the Lord’s own declaration,[58] as a god to Aaron, makes Aaron a high priest.[59] Just as Moses communed face-to-face with the Lord in actuality on Mount Sinai (shown prominently in the background), so Aaron as high priest will enter into the Lord’s presence ritually in the Tabernacle Holy of Holies each Day of Atonement.

Two priests, sons of Aaron dressed in the sacred vestments of the Levitical priesthood, stand close by at the outer veil. Much of their ministry took place in the Tabernacle courtyard where they conducted sacrifices and offerings. However, they were also permitted to enter the Holy Place. There they made offerings of incense, maintained the oil lamps, and prepared the table of shewbread.[60] The priests and their families were allowed the additional privilege of consuming the shewbread and wine each Sabbath.[61]

The ministry of the Levites was confined only to the courtyard of the temple, where they assisted the sons of Aaron in tasks such as the transportation and assembly of the Tabernacle and the handling of temple vessels. They also provided service as musicians and temple guards. In the painting they are shown standing remotely, next to the exterior curtain.

Consistent with their preferred position at Mount Sinai, away from the Lord’s presence at the foot of the mountain, the rest of the people are camped outside the sacred space, excluded even from the Tabernacle courtyard.

Figure 9. Standing in the Holy Place in the Last Days

The Why

The story of Israel’s provocations and withdrawn privileges has important lessons for our time. The eleventh chapter of Revelation, which describes the situation in the last days, opens with the angel’s instruction to John to “measure the temple of God, and the altar, and them that worship therein.”[62] By way of contrast, John is told not to measure the areas lying outside the temple complex proper — in other words, the outer courtyard. In the context of the rest of the chapter, the meaning of the angel’s instructions is clear: only those who are standing within the scope of John’s measure — in other words, within the temple itself — will receive God’s protection.[63]

Of course, the angel is not speaking to John the Revelator about the measurement of a literal physical structure, but rather of measuring or judging the community of disciples who have been called to form the living temple of God,[64] each individual in his or her differing degree of righteousness.[65] Spiritually speaking, the worshippers standing in the holy place are those who have kept their covenants.[66] These are they who, according to Revelation 14:1, will stand with the Lamb “on… mount Sion.”

By way of contrast, all individuals standing in the outer courtyard, being unmeasured and unprotected, will be, in the words of the book of Revelation, “given unto the Gentiles” to be “tread under foot”[67] with the rest of the wicked in Jerusalem. Mere association with covenant-keepers will not save unfaithful covenant-makers.[68]

Ultimately, we read in D&C 101, “every corruptible thing… that dwells upon all the face of the earth… shall be consumed.”[69] By “every corruptible thing” the verse denotes every being that is of a telestial nature. Only those who can withstand the rigors of dwelling in at least a terrestrial glory will remain on the earth during the millennial reign of Christ. In that day, only those who remain unmoved in the holy place will be able to “stand still, with the utmost assurance to see the salvation of God.”[70]

Where are the “holy places” in which disciples are to stand in the last days? In light of everything discussed above, the frequently heard suggestion that such “holy places” include temples, stakes, chapels, and homes seems wholly appropriate.[71] However, it should be remembered that what makes these places holy — and secure — are the covenants kept by those standing within. According to Jewish midrash, Sodom itself could have been a place of safety had there been a circle of as few as ten righteous individuals in the city to “pray on behalf of all of them.”[72]

As always, I appreciate the love, support, and advice of Kathleen M. Bradshaw on this article. Thanks to Stephen T. Whitlock for valuable suggestions.

Further Study

For a comprehensive discussion of the Tabernacle, its furnishings, its priesthood, and its symbolism from an LDS perspective, see M. B. Brown, Gate, chapter 3. See also the in-depth research of Michael Morales on Tabernacle history and symbolism (L. M. Morales, Tabernacle Pre-Figured).

M. Catherine Thomas has written an insightful article on the provocations of Israel (M. C. Thomas, Provocation). For an excellent presentation on the subject touching on many of the themese of the current article, see A. F. Ehat, Torah Harmony. Unfortunately, Ehat’s study has not yet been published.

For more on the idea of the layout of sacred space of Eden, including Ephrem the Syrian’s idea of the Tree of Knowledge as the veil for the sanctuary, see J. M. Bradshaw, Tree of Knowledge.

For extensive discussion of ancient conceptions and examples relating to the idea of standing in holy places, see J. M. Bradshaw, Standing in the Holy Place, freely downloadable at www.TempleThemes.net.

See this article for a related KnoWhy from Book of Mormon Central: https://knowhy.bookofmormoncentral.org/content/why-did-moroni-use-temple-imagery-while-telling-the-brother-of-jared-story

For other scripture resources relating to this lesson, see The Interpreter Foundation Old Testament Gospel Doctrine Index (https://interpreterfoundation.org/gospel-doctrine-resource-index/ot-gospel-doctrine-resource-index/) and the Book of Mormon Central Old Testament KnoWhy list (https://knowhy.bookofmormoncentral.org/tags/old-testament).

References

Anderson, Gary A., and Michael Stone, eds. A Synopsis of the Books of Adam and Eve 2nd ed. Society of Biblical Literature: Early Judaism and its Literature, ed. John C. Reeves. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1999.

Barker, Margaret. The Hidden Tradition of the Kingdom of God. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), 2007.

Beale, Gregory K. The Temple and the Church’s Mission: A Biblical Theology of the Dwelling Place of God. New Studies in Biblical Theology 1, ed. Donald A. Carson. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2004.

Benson, Ezra Taft. The Teachings of Ezra Taft Benson. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1988.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and Ronan J. Head. "The investiture panel at Mari and rituals of divine kingship in the ancient Near East." Studies in the Bible and Antiquity 4 (2012): 1-42.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. "The tree of knowledge as the veil of the sanctuary." In Ascending the Mountain of the Lord: Temple, Praise, and Worship in the Old Testament, edited by David Rolph Seely, Jeffrey R. Chadwick and Matthew J. Grey. The 42nd Annual Brigham Young University Sidney B. Sperry Symposium (26 October, 2013), 49-65. Provo and Salt Lake City, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University and Deseret Book, 2013.

———. "The ark and the tent: Temple symbolism in the story of Noah." In Temple Insights: Proceedings of the Interpreter Matthew B. Brown Memorial Conference ‘The Temple on Mount Zion,’ 22 September 2012, edited by William J. Hamblin and David Rolph Seely. Temple on Mount Zion Series 2, 25-66. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation/Eborn Books, 2014.

———. Creation, Fall, and the Story of Adam and Eve. 2014 Updated ed. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014.

———. "Standing in the Holy Place: Ancient and modern reverberations of an enigmatic New Testament prophecy." In Ancient Temple Worship: Proceedings of the Expound Symposium, 14 May 2011, edited by Matthew B. Brown, Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, Stephen D. Ricks and John S. Thompson. Temple on Mount Zion 1, 71-142. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014. http://www.templethemes.net/publications/04-Ancient%20Temple-Bradshaw.pdf.

———. Temple Themes in the Oath and Covenant of the Priesthood. 2014 update ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014.

———. "Freemasonry and the Origins of Modern Temple Ordinances." Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 15 (2015): 159-237. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/freemasonry-and-the-origins-of-modern-temple-ordinances/. (accessed May 20, 2016).

———. "Faith, hope, and charity: The ‘three principal rounds’ of the ladder of heavenly ascent." In “To Seek the Law of the Lord”: Essays in Honor of John W. Welch, edited by Paul Y. Hoskisson and Daniel C. Peterson, 59-112. Orem, UT: The Interpreter Foundation, 2017.

Brown, Matthew B. The Gate of Heaven: Insights on the Doctrines and Symbols of the Temple. American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 1999.

———. The Throne of God. American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, in preparation.

Ehat, Andrew F. 2012. A Torah Harmony (Presentation given at “The Temple on Mount Zion” Conference, Provo, Utah, September 22, 2012). In The Interpreter Foundation YouTube Channel. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r9a3UxTTDp8. (accessed April 8, 2018).

Ephrem the Syrian. ca. 350-363. "The Hymns on Paradise." In Hymns on Paradise, edited by Sebastian Brock, 77-195. Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1990.

———. ca. 350-363. Hymns on Paradise. Translated by Sebastian Brock. Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1990.

Fletcher-Louis, Crispin H. T. "Some reflections on angelomorphic humanity texts among the Dead Sea Scrolls." Dead Sea Discoveries 7, no. 3 (2000): 292-312. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4193167. (accessed January 23, 2010).

Freedman, H., and Maurice Simon, eds. 1939. Midrash Rabbah 3rd ed. 10 vols. London, England: Soncino Press, 1983.

Ginzberg, Louis, ed. The Legends of the Jews. 7 vols. Translated by Henrietta Szold and Paul Radin. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1909-1938. Reprint, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Hymns of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1948.

Leonard, Glen M. Nauvoo: A Place of Peace, A People of Promise. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2002.

Margueron, Jean-Claude. Mari: Métropole de l’Euphrate au IIIe et au début du IIe millénaire avant Jésus-Christ. Paris, France: Éditions A. et J. Picard, 2004.

Maxwell, Neal A. "Deny yourselves of all ungodliness." Ensign 25, May 1995, 66-68.

Metzger, Bruce M. Breaking the Code: Understanding the Book of Revelation. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 1993.

Milgrom, Jacob. Studies in Levitical Terminology. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1970.

Morales, L. Michael. The Tabernacle Pre-Figured: Cosmic Mountain Ideology in Genesis and Exodus. Biblical Tools and Studies 15, ed. B. Doyle, G. Van Belle, J. Verheyden and K. U. Leuven. Leuven, Belgium: Peeters, 2012.

The NET Bible. In New English Translation Bible, Biblical Studies Foundation. https://net.bible.org/. (accessed August 12, 2017).

Nibley, Hugh W. 1975. The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment. 2nd ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005.

Nickelsburg, George W. E., ed. 1 Enoch 1: A Commentary on the Book of 1 Enoch, Chapters 1-36; 81-108. Hermeneia: A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2001.

Orlov, Andrei A. "The pteromorphic angelology of the Apocalypse of Abraham." In Divine Manifestations in the Slavonic Pseudepigrapha, edited by Andrei A. Orlov. Orientalia Judaica Christiana 2, 203-15. Pisacataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2009.

Parry, Jay A., and Donald W. Parry. Understanding the Book of Revelation. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1998.

Philo. b. 20 BCE. "On Dreams." In Philo, edited by F. H. Colson and G. H. Whitaker. Revised ed. 12 vols. Vol. 5. Translated by F. H. Colson and G. H. Whitaker. The Loeb Classical Library 275, 283-579. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1934.

Pitre, Brant. Jesus and the Last Supper. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2015.

Rashi. c. 1105. The Torah with Rashi’s Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated. Vol. 2: Shemos/Exodus. Translated by Rabbi Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg. ArtScroll Series, Sapirstein Edition. Brooklyn, NY: Mesorah Publications, 1994.

Scofield, C. I., ed. The Scofield Reference Bible: The Holy Bible Containing the Old and New Testaments. New York City, NY: Ocford University Press, 1917.

Seaich, John Eugene. Ancient Texts and Mormonism: Discovering the Roots of the Eternal Gospel in Ancient Israel and the Primitive Church. 2nd Revised and Enlarged ed. Salt Lake City, UT: n. p., 1995.

Smith, Joseph Fielding, Jr. 1957-1966. Answers to Gospel Questions. 5 vols. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1979.

Smith, Joseph, Jr. The Words of Joseph Smith. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1980. https://rsc.byu.edu/archived/words-joseph-smith-contemporary-accounts-nauvoo-discourses-prophet-joseph/1843/21-may-1843. (accessed February 6, 2016).

———. 1902-1932. History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Documentary History). 7 vols. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1978.

———. 1938. Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1969.

Thomas, M. Catherine. "The provocation in the wilderness and the rejection of grace." In Sperry Symposium Classics: The Old Testament, edited by Paul Y. Hoskisson, 164-76. Provo and Salt Lake City, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2005. https://rsc.byu.edu/archived/sperry-symposium-classics-old-testament/provocation-wilderness-and-rejection-grace. (accessed November 21, 2017).

Tvedtnes, John A. "Temple prayer in ancient times." In The Temple in Time and Eternity, edited by Donald W. Parry and Stephen D. Ricks, 79-98. Provo, UT: The Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, Brigham Young University, 1999.

———. E-mail message to Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, March 8, 2010.

Welch, John W. "Counting to ten." Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 12, no. 2 (2003): 42-57, 113-14. http://publications.mi.byu.edu/publications/jbms/12/2/S00006-50be698e8c0ab5Welch.pdf. (accessed January 15, 2016).

Wenham, Gordon J. 1986. "Sanctuary symbolism in the Garden of Eden story." In I Studied Inscriptions Before the Flood: Ancient Near Eastern, Literary, and Linguistic Approaches to Genesis 1-11, edited by Richard S. Hess and David Toshio Tsumura. Sources for Biblical and Theological Study 4, 399-404. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1994.

Young, Brigham. 1857. "Attention and reflection necessary to an increase of knowledge; self-control; unity of the Godhead and of the people of God (Discourse by President Brigham Young, delivered in the Tabernacle, Great Salt Lake City, November 29, 1857)." In Journal of Discourses. 26 vols. Vol. 6, 93-101. Liverpool and London, England: Latter-day Saints Book Depot, 1853-1886. Reprint, Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1966.

Zlotowitz, Meir, and Nosson Scherman, eds. 1977. Bereishis/Genesis: A New Translation with a Commentary Anthologized from Talmudic, Midrashic and Rabbinic Sources 2nd ed. Two vols. ArtScroll Tanach Series, ed. Rabbi Nosson Scherman and Rabbi Meir Zlotowitz. Brooklyn, NY: Mesorah Publications, 1986.

Zornberg, Avivah Gottlieb. Genesis: The Beginning of Desire. Philadelphia, PA: Jewish Publication Society, 1995.

Endnotes

How shall God come to the rescue of this generation? He shall send Elijah. The law revealed to Moses in Horeb [Sinai] never was revealed to the children of Israel. He shall reveal the covenants to seal the hearts of the fathers to the children and the children to the fathers [see Malachi 4:5-6]. Anointing and sealing. Called, elected, and made sure [2 Corinthians 1:21-22. See ibid., 27 June 1839, p. 19 n. 11. Ibid., p. 302 n. 12: “Apparently it is one thing to receive the anointing and sealing blessings of the priesthood and another thing for them to be called, elected, and made sure.”]. Without father, etc. [Hebrews 7:3]. A priesthood which holds the priesthood by right from the eternal Gods, and not descended from father and mother [JST Genesis 14:28; JST Hebrews 7:3].

According to Andrew F. Ehat and Lyndon W. Cook further explained (ibid., pp. 143-144 n. 5):

Undoubtedly, if, at this stage of Joseph Smith’s thinking [1 May 1842], he had been asked, “What was taken away when Moses died?” he would not have answered, “the Endowment ordinances as they were given in Kirtland.” Those ordinances there administered were identical for the Aaronic and Melchizedek Priesthoods (see J. Smith, Jr., Documentary History, 5:1-2 or ibid., p. 137). … Moreover, the sacred vestments of the priesthood shown by the pattern of God for the Levitical order of the temple service (Exodus 28, 39, and 40:1-33) were not restored in Kirtland, but were given in Nauvoo.

The Prophet taught that “Christ fulfilled all righteousness in becoming obedient to the law which [He] Himself had given to Moses on the mount and thereby magnified it and made it honorable instead of destroying it” (J. Smith, Jr., Words, Franklin D. Richards “Scriptural Items”, 29 January 1843, pp. 162-153).

Within modern temple ordinances, as within the sacrament, animal sacrifice is replaced by the offering of oneself. Such offerings are “memorials of … sacrifices by the sons of Levi” (&C 124:39, emphasis added. See M. B. Brown, Gate, p. 242) — in other words, symbolic rather than literal reenactments of ancient temple practices that required the shedding of blood. Illuminating the difference between the ordinances of the “preparatory” (D&C 84:26) Aaronic priesthood and those of the “holy” Melchizedek priesthood “after the Order of the Son of God” (D&C 107:3), Elder Neal A. Maxwell taught that “real, personal sacrifice never was placing an animal on the altar. Instead, it is a willingness to put the animal in us upon the altar and letting it be consumed!” (N. A. Maxwell, Deny, p. 68).

Similarly, in Genesis 14:18 Melchizedek does not offer animal sacrifices to God, but “presents only the memorials of sacrifice, bread and wine” (C. I. Scofield, Scofield Reference Bible, Genesis 14:18, p. 23, emphasis in original).

For more on this topic, see J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, Excursus 33: The Restoration of Sacrifice, pp. 609–610.

The keys are certain signs and words by which false spirits and personages may be detected from true, which cannot be revealed to the elders till the temple is completed. The rich can only get them in the temple; the poor may be them on the mountain top as did Moses. … There are signs in heaven, earth, and hell. The elders must know them all to be endowed with power. … No one can truly say he knows God until he has handled something, and this can only be in the Holiest of Holies” (John 17:3; 1 John 1:1-3; 3 Nephi 11:14-17; D&C 45:51-53; 50:45; 64:10; 84:98 (see ibid., 27 June 1839, p. 19 n. 9); 93:1, 132:22-24; JST Matthew 7:33 (“Ye never knew me”); and JST Matthew 25:11 (“Ye know me not”).

Elsewhere, the Prophet taught:

God … visited Moses in the bush [and] … said “Thou shalt be a god unto the children of Israel” [compare Exodus 4:15; cf. Exodus 7:1: “a god to pharaoh”]. God said, “Thou shalt be a god unto Aaron and he shall be thy spokesman” [see Exodus 4:16; 7:1]. I believe in these gods that God reveals as gods. To be sons of God [Job 38:7; John 1:12; Romans 8:14, 19; 1 John 3:1-2; 3 Nephi 9:17; Moroni 7:26, 48; D&C 11:30; 39:4; 45:8; 76:24, 58 (50-60); Moses 6:68 (57-68); 7:1; 8:13-22 (cf. Genesis 6:1-8)] and all can cry “Abba, Father” [Romans 8:15 (14-17)]. Sons of God who exalt themselves to be gods even from before the foundation of the world and are all the only gods I have a reverence for [Abraham 3:22-4:1].

The verb נָסָה (nasah) means “to test, to tempt, to prove.” It can be used to indicate things are tried or proven, or for testing in a good sense, or tempting in the bad sense, i.e., putting God to the test. In all uses there is uncertainty or doubt about the outcome. Some uses of the verb are positive: If God tests Abraham in Genesis 22:1, it is because there is uncertainty whether he fears the Lord or not; if people like Gideon put out the fleece and test the Lord, it is done by faith but in order to be certain of the Lord’s presence. But here, when these people put God to the test ten times, it was because they doubted the goodness and ability of God, and this was a major weakness. They had proof to the contrary, but chose to challenge God.

This sin was so serious that the chief participants in the act were executed by the sons of Levi, and the Lord brought a plague upon the remainder of the people (see Exodus 32:25-35; see also JST Exodus 32:14). The Lord even refused, in his anger, to allow Moses to see his face when they met together (see JST Exodus 33:18-25). The Lord threatened to destroy the entire nation except for Moses and commanded the Israelites to remove their “ornaments” (Exodus 33:4-6). The Septuagint (or ancient Greek version of the Old Testament) adds that the Israelites had on “robes of glory” and they were required to remove them also. These robes may be related to the”garments … for glory” (i.e., temple robes) worn by the Israelite priests (see Exodus 28:2).

“Here I stand there before you, on the rock in Horeb” (Exodus 17:6), which means, “this I, the manifest, Who am here, am there also, am everywhere, for I have filled all things. I stand ever the same immutable, before you or anything that exists came into being, established on the topmost and most ancient source of power, whence showers forth the birth of all that is.…” And Moses too gives his testimony to the unchangeableness of the deity when he says “they saw the place where the God of Israel stood” (Exodus 24:10), for by the standing or establishment he indicates his immutability. But indeed so vast in its excess is the stability of the Deity that He imparts to chosen natures a share of His steadfastness to be their richest possession. For instance, He says of His covenant filled with His bounties, the highest law and principle, that is, which rules existent things, that this god-like image shall be firmly planted with the righteous soul as its pedestal… And it is the earnest desire of all the God-beloved to fly from the stormy waters of engrossing business with its perpetual turmoil of surge and billow, and anchor in the calm safe shelter of virtue’s roadsteads. See what is said of wise Abraham, how he was “standing in front of God” (Genesis 18:22), for when should we expect a mind to stand and no longer sway as on the balance save when it is opposite God, seeing and being seen?… To Moses, too, this divine command was given: “Stand here with me” (Deuteronomy 5:31), and this brings out both the points suggested above, namely the unswerving quality of the man of worth, and the absolute stability of Him that IS. (modified by Fletcher-Louis from Philo, Dreams, 2:32, 221-2:33, 227, pp. 543, 545).

Fletcher-Louis comments on parallels between Philo, 4Q377 from Qumran, and the Pentateuch:

Like Philo, 4Q377 is working with Deuteronomy 5:5, the giving of the Torah, and perhaps Exodus 17:6. Both texts think standing is a posture indicative of a transcendent identity in which the righteous can participate and of which Moses is the pre-eminent example. With the stability of standing is contrasted the corruptibility of motion, turmoil and storms, which is perhaps reflected in the tension between Israel’s “standing” (lines 4 and 10) and her “trembling” (line 9) before the Glory of God in the Qumran text. Whether this and other similar passages in Philo (cf. esp. Sacr. 8-10; Post. 27-29) are genetically related to 4Q377 is not certain, but remains a possibility. (C. H. T. Fletcher-Louis, Reflections, p. 304)

Will it relieve their horrors there,

To recollect their stations here?

How much they heard, how much they knew,

How long amongst the wheat they grew!