An Old Testament KnoWhy[1]

for Gospel Doctrine Lesson 5:

“If Thou Doest Well, Thou Shalt Be Accepted” (Moses 5-7) (JBOTL05C)

[See the link to video supplements for this lesson at the end of this article under “Further Study.”]

Figure 1. George Campfield, fl. 1861: Enoch, Creation Window, All Saints Church, Selsley, England, 1861. This stained glass window, commissioned from the company of craftsmen headed by William Morris, shows Enoch standing in heaven following his final ascension.

Question: Some say that Joseph Smith drew on ancient stories about Enoch not found in the Bible as he translated the chapters on Enoch in Moses 6-7. How similar are the stories of Enoch in ancient accounts to modern scripture? And could Joseph Smith have been aware of them?

Summary: Although an English translation of the Ethiopian book of 1 Enoch appeared in 1821, the ancient manuscripts that are most relevant to the LDS story of Enoch were not available during Joseph Smith’s lifetime. The Qumran Book of Giants, discovered in 1948, contains striking resemblances to Moses 6-7, ranging from general themes in the story line to specific occurrences of rare expressions in corresponding contexts. It would be thought remarkable if any nineteenth-century document were to exhibit a similar density of close resemblances with this small collection of ancient fragments, but to find such similarities in appropriate contexts relating in each case to the story of Enoch is astonishing.

The Know

Both in the expansive nature of its content and the eloquence of its expression, Terryl and Fiona Givens consider the LDS account of Enoch as perhaps the “most remarkable religious document published in the nineteenth century.”[2] It was produced early in Joseph Smith’s ministry — in fact in the same year as the publication of the Book of Mormon — as part of a divine commission to “retranslate” the Bible.[3] Writing the account of Enoch found today in Moses 6-7 appears to have occupied a few days of the Prophet’s attention sometime between 30 November and 31 December 1830.

Joseph Smith’s “Book of Enoch” provides “eighteen times as many column inches about Enoch… than we have in the few verses on him in the Bible. Those scriptures not only contain greater quantity [than the Bible] but also … contain … [abundant] new material about Enoch on which the Bible is silent.”[4] It seems impossible that this new material was derived from deep study of the scriptures[5] or that it was largely absorbed from Masonic or hermetical influences.[6] Hence, the most popular suggestion from non-Mormon scholars is that Joseph Smith derived important themes in the LDS stories of Enoch from exposure to ancient Enoch manuscripts from outside the Bible, in particular 1 Enoch.[7]

Could Joseph Smith have borrowed significant portions of his accounts of Enoch from other sources? In his 2010 master’s thesis from Durham University, Salvatore Cirillo[8] cites and amplifies the arguments of Michael Quinn[9] that the available evidence that Joseph Smith had access to published works related to 1 Enoch has moved “beyond probability — to fact.” He sees no other explanation than this for the substantial similarities that he finds between the book of Moses and the pseudepigraphal Enoch literature.[10] However, after having reflected on the evidence with the more rigorous approach of a seasoned historian about the availability of the 1821 English translation of 1 Enoch to the Prophet, Richard L. Bushman concluded differently:[11] “It is scarcely conceivable that Joseph Smith knew of Laurence’s Enoch translation.”

Just as important, even if 1 Enoch had been available to the Prophet, a study y LDS historian Jed Woodworth reveals that the principal themes of “Laurence’s 105 translated chapters do not resemble Joseph Smith’s Enoch in any obvious way.”[12] Indeed, apart from the shared prominence of the Son of Man motif in 1 Enoch’s Book of the Parables and the book of Moses[13] and one or two general themes in Enoch’s visions of Noah,[14] little of great substance in common between 1 Enoch and modern scripture. After careful study of the two works on Enoch, Woodworth succinctly concluded: “Same name, different voice.”[15]

Note that since Joseph Smith was aware that the biblical book of Jude quotes Enoch[16] — more specifically 1 Enoch itself — the most obvious thing he could have done to bolster his case for the authenticity of the book of Moses (if he were a conscious deceiver) would have been to include the relevant verses from Jude somewhere within his revelations on Enoch. But this the Prophet did not do.

For such reasons, it is increasingly apparent that despite all the spilled ink spent in looking for significant parallels to the Prophet’s revelations on Enoch in 1 Enoch, the most striking resemblances are not found in that work, but rather in related pseudepigrapha such as 2 Enoch, 3 Enoch, and the Qumran Book of Giants.

Reflecting the trend of scholars to look beyond 1 Enoch for these resemblances, LDS scholar Cheryl L. Bruno, in a 2014 article in the Journal of Religion and Society,[17] tries to make the case that Jewish Enoch traditions, mediated by Masonic accounts that Joseph Smith presumably encountered, significantly influenced Mormon accounts of Enoch. In support of her claims, she notes, in addition to 1 Enoch and other Jewish sources, similarities in 2 Enoch and the LDS Enoch in “Enoch’s call to preach” [18] and his divine transfiguration.[19] She also cites 3 Enoch in relation to Enoch’s enthronement.[20] Surprisingly and disappointingly, apart from a short reference relating to Enoch as a scribe for divine tablets,[21] she does not mention the prominent resemblances between Moses 6-7 and the Book of Giants.

However, Cirillo did not let these significant resemblances go unnoticed, having argued in his master’s thesis in strong terms that Joseph Smith must have known about the Qumran Book of Giants. He writes:[22]

Nibley‘s own point that Mahujah and Mahijah from the EPE share their name with Mahaway in the [Book of Giants (BG)] is further evidence that influence [from pseudepigraphal books of Enoch] occurred [in Joseph Smith’s Enoch writings]. And additional proof of Smith‘s knowledge of the BG is evidenced by his use of the codename Baurak Ale.[23]

What goes unmentioned in Cirillo’s arguments for the influence of Enoch pseudepigrapha on Moses 6-7 is that, apart from 1 Enoch, none of the significant Jewish Enoch manuscripts were available in English translation during Joseph Smith’s lifetime. Indeed, Cirillo’s strongest arguments for the Prophet’s having been influenced by these ancient works comes from the Qumran Book of Giants, a book that was not discovered until 1948. Cirillo offers no attempt at an explanation for how a manuscript that was unknown until the mid-twentieth century could have influenced LDS accounts of Enoch, written in 1830-31.

In addition, although Bruno takes a different route in arguing that resemblances to ancient Jewish pseudepigrapha in Joseph Smith’s Enoch writings were mediated to an important degree by (as it is argued) the Prophet’s early exposure to the traditions of Freemasonry, it should be remembered that the most numerous, significant, and specific echoes of antiquity in the book of Moses are not found in the Masonic literature but rather only in the Jewish traditions themselves.

This is not to say that the rituals, ideas, and ideals of Freemasonry were not important to Joseph Smith, particularly after he became institutionally involved during the Nauvoo period from 1839 onward.[24] However, what is important in the context of a discussion about possible influences on Joseph Smith’s translation of Moses 6-7 in 1830 is that one must not overstate resemblances with Freemasonry while understating more relevant and specific affinities to ancient traditions not present in Freemasonry — thus making proverbial molehills into mountains while reducing mountains to molehills.

In summary, it would have been impossible for Joseph Smith to have been aware of the most important affinities to ancient literature in his Enoch revelations by 1830, regardless of whether one claims that he got them by direct access to English translations of important Jewish Enoch manuscripts (other than, perhaps, 1 Enoch) or that his exposure was mediated by a knowledge of Masonic traditions.

After a brief survey of some of the ancient affinities of the story of Enoch in Moses 6-7 throughout the wider Jewish literature, we will focus more specifically on the most important of these writings: the Qumran Book of Giants. Even a summary of all these important topics had made this article much longer than others published so far in this series. More extensive discussions of these topics by LDS authors can be found elsewhere.[25]

Ancient Affinities in Jewish Enoch Pseudepigrapha

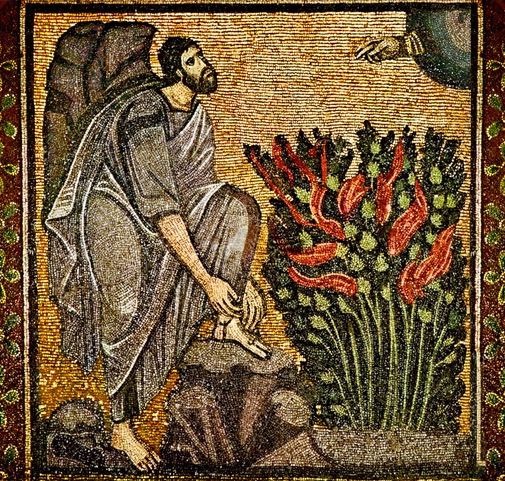

Figure 2. Moses and the Burning Bush, St. Catherine’s Monastery, ca. 548-560.

Enoch’s call. LDS scholar Stephen Ricks has shown how the six characteristic features of the Old Testament narrative call pattern identified by Norman Habel are shown in the commissioning of Joseph Smith’s Enoch.[26] According to non-Mormon scholar Samuel Zinner,[27] the ideas behind the unusual wording found within Enoch’s prophetic commission in the book of Moses arose in the matrix of the ancient Enoch literature.[28]

“Rivers shall turn from their course.” Joseph Smith’s Enoch will manifest God’s power in both his words and, notably, in his actions:[29]

… the mountains shall flee before you, and the rivers shall turn from their course

Later in the book of Moses we read the fulfillment of this promise: “[S]o great was the faith of Enoch that … the rivers of water were turned out of their course.”[30] Compare the Enoch’s experience in the book of Moses to a Mandaean Enoch account:[31]

The [Supreme] Life replied, Arise, take thy way to the source of the waters, turn it from its course … At this command Tavril [the angel speaking to Enoch] indeed turned the pure water from its course …

We find no account of a river’s course turned by anyone in the Bible. However, such a story appears in this pseudepigraphal account and in its counterpart in Joseph Smith’s revelations — in both instances within the story of Enoch.

Figure 3. Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (Le Carvage), 1571-1610: David with the Head of Goliath, 1607. In a prophecy “of old” that is later applied to David we read: “I have set a youth above the warrior; I have [exalted] a young man over the people.”>[32] The youth (Hebrew bahur) who is set above the warrior (Hebrew gibbor) recalls Enoch’s victory as a “lad” (Hebrew na’ar) over the warriors (Hebrew gibborim) in the Dead Sea Scrolls Book of Giants and in the book of Moses.[33]

Figure 4. Franz Johansen, 1928-: Resurrection, Brigham Young University Sculpture Garden, Provo, Utah. [37] The scene of celestial clothing recounted in 2 Enoch 22:8 recalls a vision that President Lorenzo Snow, then an apostle, received of his own resurrection. His journal records:[38] “I heard a voice calling me by name, saying: “He is worthy, he is worthy, take away his filthy garments.” My clothes were then taken off piece by piece and a voice said: “Let him be clothed, let him be clothed.” Immediately, I found a celestial body gradually growing upon me until at length I found myself crowned with all its glory and power. The ecstasy of joy I now experienced no man can tell, pen cannot describe it.”

Figure 5. Gustav Kaupert, 1819-1897: Jesus Christ, 1880.[45] This magnificent bust now stands in The Protestant Church of the Redeemer. The church is housed in the former Roman Palace Basilica of Constantine (Aula Palatina), built in the early fourth century in what is now Trier, Germany. The full-size statue was broken to pieces after World War II, but in 2006, following loving restoration, the bust was given a place of honor in the church.

Figure 5. Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, 1606-1669: Jeremiah Laments the Destruction of Jerusalem, 1630.

A chorus of weeping. In a vision of Enoch found in the book of Moses, three distinct parties weep for the wickedness of mankind: God,[55] the heavens,[56] and Enoch himself.[57] In addition, a fourth party, the earth, mourns — though does not specifically weep — for her children.[58] Daniel Peterson[59] has discussed the interplay among the members of this chorus of weeping voices, citing the arguments of non-LDS biblical scholar J. J. M. Roberts[60] that identify three similar voices within the laments of the book of Jeremiah: the feminine voice of the mother of the people (corresponding in the Book of Moses to the voice of the earth, the “mother of men”[61]), the voice of the people (corresponding to Enoch), and the voice of God Himself. In addition, with regard to the complaints of the earth described in Moses 7:48-49, valuable articles by Andrew Skinner[62] and Peterson,[63] again following Nibley’s lead,[64] discuss interesting parallels in ancient sources. Finally, taking up the subject of previously neglected voices of weeping — namely the weeping of Enoch and that of the heavens — David Larsen, Jacob Rennaker, and I have written a comparative study of ancient texts.[65]

Translation of Enoch and his city. Genesis implies that Enoch escaped death by being taken up alive into heaven.[66] In a significant addition to the biblical record, the Book of Moses states that not only Enoch but his entire city was eventually received up into heaven.[67] Two late accounts preserve echoes of a similar motif. In Adolph Jellenik’s translation of Jewish traditions, Bet ha-Midrasch,[68] we find the account of a group of Enoch’s followers who steadfastly refused to leave him as he journeyed toward the place where he was going to be taken up to heaven.[69] Afterward, a group of kings came to find out what happened to these people. After searching under large blocks of snow they unexpectedly found at the place, they failed to discover any remains of Enoch or of his followers. In a Mandaean Enoch fragment,[70] a group of the prophet’s adversaries complain that Enoch and those who had gone to heaven with him have escaped their reach: “By fleeing and hiding the people on high have ascended higher than us. We have never known them. All the same, there they are, clothed with glory and splendors. … And now they are sheltered from our blows.”

In addition to these accounts alluding to a group who rose with Enoch to heaven, David Larsen provides a valuable discussion that includes “examples in early Jewish and early Christian literature that depict this motif in a different way. Although they do not feature Enoch or his city explicitly, there is a recurring theme in some of the texts that corresponds to the idea of a priestly figure who leads a community of priests in an ascension into the heavenly realm.”[71]

We now focus our attention on the Book of Giants, which contains surprising resonances with Joseph Smith’s book of Enoch at both the large and the small scale.

Enoch’s Mission to the Gibborim in the Qumran Book of Giants

The Book of Giants is a collection of fragments from an Enochic book discovered at Qumran, the location of the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Though it is missing from the Ethiopic book of 1 Enoch[72] and resembles little else in the Enoch tradition, material related to the Book of Giants already had been found elsewhere in fragmentary form.[73] Some of the fragments showed that the “composition is at least five hundred years older than previously thought”[74] and thus they help us “to reconstruct the literary shape of the early stages of the Enochic tradition.”[75] Although the Book of Giants scarcely fills three pages in the English translation of Martinez, we find in it the most extensive series of parallels between a single ancient text and Joseph Smith’s Enoch writings.

The wickedness of the gibborim. The term “giants” in the title of the book is misleading. Actually, this book describes two different groups of individuals, referred to in Hebrew as the gibborim and the nephilim. In the Bible, gibborim almost always referred to a “mighty hero” or “warrior” and only later came to be interpreted in some cases as “giant.”[76] Correctly understanding the distinctions among these groups is important because Joseph Smith specifically differentiated the “giants” from Enoch’s other adversaries.[77]

Figure 6. William Blake, 1757-1827: Sketch for “War Unchained by an Angel — Fire, Pestilence, and Famine Following, ca. 1780-1784. Speaking as if he were standing before this scene, John Bright (1811–1889), a Quaker, movingly addressed the English House of Commons in opposition to the Crimean War: “The angel of death has been abroad throughout the land; you may almost hear the beating of his wings. There is no one as of old … to sprinkle with blood the lintel and the two side-posts of our doors, that he may spare and pass on; he takes his victims from the castle of the noble, the mansion of the wealthy, and the cottage of the poor and lowly.”[78]

And the children of men were numerous upon all the face of the land. And in those days Satan had great dominion among men, and raged in their hearts; and from thenceforth came wars and bloodshed; and a man’s hand was against his own brother, in administering death, because of secret works, seeking for power.

The Book of Giants account likewise begins with references to “slaughter, destruction, and moral corruption”[81] that filled the earth.[82] The mention of “secret works” and “administering death”[83] in the book of Moses recalls a similar description in the Book of Giants:[84] “they knew the se[crets[85] … ] and they killed ma[ny … ].” Elsewhere the Qumran manuscripts refer to the spread of the “mystery of wickedness.”[86]

“A wild man.” In the book of Moses, Enoch’s preaching first attracts listeners out of pure curiosity:[87]

And they came forth to hear him, upon the high places, saying unto the tent-keepers: Tarry ye here and keep the tents, while we go yonder to behold the seer, for he prophesieth, and there is a strange thing in the land; a wild man hath come among us.

The term “wild man”[88] is used in only one other place in the Bible, as part of Jacob’s prophecy about the fate of Ishmael. We see a more fitting parallel in the Book of Giants — if the translation by Wise is correct — where the wicked leader of the gibborim, ’Ohya, boasts that he is called “the wild man,”[89] just as in the book of Moses the same term is used — sarcastically — to describe Enoch.

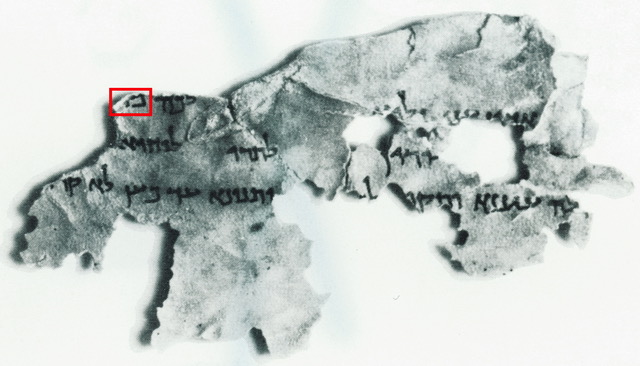

Figure 7. Fragment of the Qumran Book of Giants (4Q203) containing the first part of the personal name MḤWY (outlined in red).[90] In modern translations, the name is usually transliterated as “Mahawai.” Hugh Nibley was the first to suggest a correspondence between this Book of Giants character and the names Mahijah/Mahujah in the book of Moses.A HREF=”#_edn91″ NAME=”_ednref91″>[91] Unlike many of the other poorly preserved Aramaic fragments of the Book of the Giants, the translation of this one is straightforward: “5 [ … ] to you, Mah[awai … ] 6 the two tablets [ … ] 7 and the second has not been read up till now [ … ].”[92]

In Joseph Smith’s story of Enoch, Mahijah appears out of nowhere as the only named character in the account besides Enoch himself:[94]

And there came a man unto him, whose name was Mahijah, and said unto him: Tell us plainly who thou art, and from whence thou comest?

In the book of Moses, the name “Mahijah”[95] appears a second time in a different form, namely “Mahujah.”[96] Notably, in the Masoretic Hebrew text of the Bible the variants MḤYY [= Mahija-] and MḤWY [= Mahuja-] both appear in a single verse (with the suffix “-el”) as references to the same person, namely Mehuja-el.[97] Because the King James translation renders both variants of the Hebrew name identically in English, Joseph Smith would have had to access and interpret the Hebrew text to see that there were two versions of the name. But there is no evidence that he or anyone else associated with the translation of Moses 6-7 knew how to read Hebrew at that time or, for that matter, even had access to a Hebrew Bible.

Even if someone were to claim that Joseph Smith became aware of these two variants by examining the Hebrew text, it would still be difficult to explain why, assuming that he did indeed possess this information, the Prophet would have chosen not to normalize the two variant versions of the name into a single version in the book of Moses, as is almost always done in translations of Genesis 4:18. Instead, each of the attested variants of the name is included in the book of Moses in appropriate contexts, preserving both ancient traditions. Moreover, Joseph Smith’s versions of the name omit the suffix “-el,”[98] thus differing from the Hebrew text of the Bible and according appropriately with its Dead Sea Scrolls[99] equivalent in the Book of Giants.

There are intriguing similarities between Mahijah in Joseph Smith’s book of Moses and Mahawai in the Book of Giants not only in their names but also in their respective roles. Hugh Nibley observes:[100]

The only thing the Mahijah in the book of Moses is remarkable for is his putting of bold direct questions to Enoch. And this is exactly the role, and the only role, that the Aramaic Mahujah plays in the story.

Mahijah is sent to Enoch. In the Book of Giants, we read the report of a series of dreams that troubled the gibborim. The dreams “symbolize the destruction of all but Noah and his sons by the Flood.”[101] In an impressive correspondence to the questioning of Enoch by Mahijah in the book of Moses, the gibborim send Mahawai to “consult Enoch in order to receive an authoritative interpretation of the visions.”[102] In the Book of Giants, we read:[103]

[Then] all the [gibborim and the Nephilim] … called to [Mahujah] and he came to them. They implored him and sent him to Enoch, the celebrated scribe[104] and they said to him: “Go… and tell him to [explain to you] and interpret the dream…”[105]

Cirillo comments: “The emphasis that [Joseph] Smith places on Mahijah’s travel to Enoch is eerily similar to the account of Mahawai to Enoch in the [Book of Giants].”[106]

Secret combinations. It is interesting to speculate as to whether the Book of Giants Mahujah (who elsewhere describes himself as a “son of Baraq’el”[107]) might be identified with the biblical Mehuja-el, who was a descendant of Cain and the grandfather of the wicked Lamech. Note that in the book of Moses, Mehuja-el’s grandson, like the other “sons of men,”[108] “entered into a covenant with Satan after the manner of Cain.”[109] Similarly, in 1 Enoch[110] we read that a group of conspirators, here depicted as fallen sons of God, “all swore together and bound one another with a curse.” Elsewhere in 1 Enoch we learn additional details about that oath:[111]

This is the number of Kasbe’el, the chief of the oath, which he showed to the holy ones when he was dwelling on high in glory, and its (or “his”) name (is) Beqa. This one told Michael that he should show him the secret name, so that they might mention it in the oath, so that those who showed the sons of men everything that was in secret might quake at the name and the oath.

The passages in 1 Enoch are reminiscent of a passage in the book of Moses that describes a “secret combination” that had been in operation “from the days of Cain.”[112] As to the deadly nature of the oath, we read in the book of Moses: “Swear unto me by thy throat, and if thou tell it thou shalt die,”[113] just as in 1 Enoch the conspirators “bound one another with a curse.”[114]

In 1 Enoch, the conspirators agreed on their course of action by saying:[115] “Come, let us choose for ourselves wives from the daughters of men.” Likewise, in the book of Moses, Mehuja-el’s grandson became infamous because he “took unto himself… wives”[116] to whom he revealed the secrets of their wicked league (to the chagrin of his fellows).[117] In 1 Enoch, as in the book of Moses,[118] we also read specifically of how “they all began to reveal mysteries to their wives and children.”[119]

A land of righteousness. In answer to the second part of Mahijah’s question, Joseph Smith’s Enoch says:[120]

And he said unto them: I came out from the land of Cainan, the land of my fathers, a land of righteousness unto this day.

Amplifying the book of Moses description of Enoch’s home as a “land of righteousness,” the leader of the gibborim in the Book of Giants says that his “opponents”[121] “… reside in the heavens and live with the holy ones.”[122]

In the book of Moses, Enoch describes the setting for his vision:

42 And it came to pass, as I journeyed from the land of Cainan, by the sea east, I beheld a vision …

Enoch’s vision as he travelled “by the sea east”[123] recalls the direction of his journey in 1 Enoch 20-36 where he traveled “from the west edge of the earth to its east edge.”[124] Elsewhere 1 Enoch[125] records a vision that Enoch received “by the waters of Dan,” arguably a “sea east.”[126]

A “book of remembrance.” In preaching to the people, the Enoch of the book of Moses refers to a “book of remembrance”[127] in which the words of God and the actions of the people were recorded. Correspondingly, in the Book of Giants, a book in the form of “two stone tablets”[128] is given by Enoch to Mahujah to stand as a witness of “their fallen state and betrayal of their ancient covenants.”[129] In the book of Moses, Enoch says the book is written “according to the pattern given by the finger of God.”[130] This may allude to the idea that a similar record of their wickedness is kept in heaven[131] as attested in 1 Enoch:[132]

Do not suppose to yourself nor say in your heart that they do not know nor are your unrighteous deeds seen in heaven, nor are they written down before the Most High. Henceforth know that all your unrighteous deeds are written down day by day, until the day of your judgment.

As Enoch is linked with the book of remembrance in the book of Moses, so he is described in the Testament of Abraham as the heavenly being who is responsible for recording the deeds of mankind so that they can be brought into remembrance.[133] Likewise, in Jubilees 10:17 we read:[134] “Enoch had been created as a witness to the generations of the world so that he might report every deed of each generation in the day of judgment.”

In the book of Moses, Enoch’s reading of the book of remembrance put the people in great fear:[135]

And as Enoch spake forth the words of God, the people trembled, and could not stand in his presence.

Likewise, in the Book of Giants,[136] we read that the leaders of the mighty warriors “bowed down and wept in front of [Enoch].” 1 Enoch describes a similar reaction after Enoch finished his preaching:[137]

Then I [i.e., Enoch] went and spoke to all of them together. And they were all afraid and trembling and fear seized them. And they asked that I write a memorandum of petition[138] for them, that they might have forgiveness, and that I recite the memorandum of petition for them in the presence of the Lord of heaven. For they were no longer able to speak or to lift their eyes to heaven out of shame for the deeds through which they had sinned and for which they had been condemned.… and they were sitting and weeping at Abel-Main,[139] … covering their faces.

Conceived in sin. Among the declarations that Joseph Smith’s Enoch makes to his hearers from the book of remembrance is that their children “are conceived in sin.”[140] This has nothing to do with the concept of “original sin” but rather is the result of their own moral transgressions. As Nibley expressed it:[141] “[T]he wicked people of Enoch’s day … did indeed conceive their children in sin, since they were illegitimate offspring of a totally amoral society.” The relevant passage in the Book of Giants reads:[142] “Let it be known to you th[at … your activity and that of [your] wive[s and of your children … through your fornication.”[143]

A note of hope. Both the Qumran and the Joseph Smith sermons of Enoch “end on a note of hope”[144] — a feature unique to these two Enoch accounts:[145]

If thou wilt turn unto [God], and hearken unto my voice, and believe, and repent of all thy transgressions …

In the Book of Giants, Enoch also gives hope to the wicked through repentance:[146] “Now, then, unfasten your chains [of sin]… and pray.”[147] In addition, Reeves[148] conjectures that another difficult-to-reconstruct phrase in the Book of Giants might also be understood as an “allusion to a probationary period for the repentance of the Giants.”[149]

Defeat of the gibborim by Enoch. Any conjectured move toward repentance was temporary, however, and eventually Enoch’s enemies began to attack, as we read in the book of Moses:[150]

And so great was the faith of Enoch that he led the people of God, and their enemies came to battle against them; and he spake the word of the Lord, and the earth trembled, and the mountains fled, even according to his command; and the rivers of water were turned out of their course; and the roar of the lions was heard out of the wilderness …

Similarly, in the Book of Giants, ’Ohya, a leader of the gibborim, gives a description of his defeat in a great battle:[151]

[… I am a] [mighty warrior],[152] and by the mighty strength of my arm and my own great strength[153] [I went up against a]ll mortals, and I have made war against them; but I am not … able to stand against them.

Of special note is a puzzling phrase in some translations of the Book of Giants that immediately follows the description of the battle:[154] “… the roar of the wild beasts has come and they bellowed a feral roar.” Remarkably the book of Moses account has a similar phrase following the battle description, recording that “the roar of the lions was heard out of the wilderness.”

Figure 8. William Blake, 1757-1827: The Primaeval Giants Sunk in the Soil, 1824-1827. In a scene from Dante, giants are sunk to their waists in a well whose massive drop leads to Cocytus, a great frozen lake of the lowest region of hell. Their defiant rebellion was the more terrible and destructive because of the coupling of their evil will with the brute force of their mighty stature. Now reduced to pale mountainous shapes amidst the chaos, they stand, in Blake’s depiction, eternally unmoved by the sharp fires of lightning above and the rude blasts of icy storm winds swirling upward from below.

Destruction and confinement of the gibborim. Both the book of Moses and the Book of Giants contain a “prediction of utter destruction and the confining in prison that is to follow”[155] for the gibborim. From the book of Moses we read:[156]

But behold, these … shall perish in the floods; and behold, I will shut them up; a prison have I prepared for them.

Similarly, in the Book of Giants we read:[157] “he imprisoned us and has power [ov]er [us].”

Explanations for book of Moses resemblances to the Book of Giants. The only attempt of which I am aware to explain how a manuscript discovered in 1948 could have influenced a work of scripture translated in 1830-31 comes from remembrances by two individuals about the well-known Aramaic scholar Matthew Black, who collaborated with Jozef Milik in the first translation of the fragments of the Book of Giants into English in 1976. Black was approached by Gordon C. Thomasson after a guest lecture at Cornell University, during a year that Black spent at the Institute of Advanced Studies at Princeton (1977–1978).[158] According to Thomasson’s account:[159]

I asked Professor Black if he was familiar with Joseph Smith’s Enoch text. He said he was not but was interested. He first asked if it was identical or similar to 1 Enoch. I told him it was not and then proceeded to recite some of the correlations Dr. [Hugh] Nibley had shown with Milik and Black’s own and others’ Qumran and Ethiopic Enoch materials. He became quiet. When I got to Mahujah,[160] he raised his hand in a “please pause” gesture and was silent. Finally, he acknowledged that the name Mahujah “could not have come from 1 Enoch.” He then formulated a hypothesis, consistent with his lecture, that a member of one of the esoteric groups he had described previously [i.e., clandestine groups who had maintained, sub rosa, a religious tradition based in the writings of Enoch that pre-dated Genesis] must have survived into the 19th century, and hearing of Joseph Smith, must have brought the group’s Enoch texts to New York from Italy for the prophet to translate and publish.

At the end of our conversation he expressed an interest in seeing more of Hugh’s work. I proposed that Black should meet with Hugh, gave him the contact information. He contacted Hugh the same day, as Hugh later confirmed to me. Soon Black made a previously unplanned trip to Provo, where he met with Hugh for some time. Black also gave a public guest lecture but, as I was told, in that public forum would not entertain questions on Moses.

Hugh Nibley recorded a conversation with Matthew Black that apparently occurred near the end of the latter’s 1977 visit to BYU. Nibley asked Black if he had an explanation for the appearance of the name Mahujah in the Book of Moses, and reported his answer as follows: “Well, someday we will find out the source that Joseph Smith used.”[161]

Figure 9. Enoch Window at Canterbury Cathedral, ca. 1178-1180. Enoch is shown here with upraised hands in the traditional attitude of prayer. The right hand of God emerges from the cloud to grasp the wrist of Enoch and lift him to heaven

Summary. Note that the parallels with the Book of Giants we have cited are not drawn at will from a large corpus of Enoch manuscripts but rather are concentrated in a scant three pages of Qumran fragments, as published in the translation of Martinez. These resemblances range from general themes in the story line (secret works, murders, visions, earthly and heavenly books of remembrance that evoke fear and trembling, moral corruption, hope held out for repentance, and the eventual defeat of Enoch’s adversaries in battle, ending with their utter destruction and imprisonment) to specific occurrences of rare expressions in corresponding contexts. It would be thought remarkable if any nineteenth-century document were to exhibit a similar density of close resemblances with this small collection of ancient fragments, but to find such similarities in appropriate contexts relating in each case to the story of Enoch is astonishing.

According to the eminent Yale professor and Jewish literary scholar Harold Bloom, Joseph Smith’s ability to produce writings on Enoch so “strikingly akin to ancient suggestions” stemmed from his “charismatic accuracy, his sure sense of relevance that governed biblical and Mormon parallels.” Having studied the life and revelations of the Prophet, Bloom concludes: “I hardly think that written sources were necessary.” While expressing “no judgment, one way or the other, upon the authenticity” of LDS scripture, he found “enormous validity” in these writings and could “only attribute to [the Prophet’s] genius or daemon” his ability to “recapture … crucial elements in the archaic Jewish religion … that had ceased to be available either to normative Judaism or to Christianity, and that survived only in esoteric traditions unlikely to have touched [Joseph] Smith directly.”[162]

The Why

Harold Bloom has called the book of Moses and the book of Abraham two of the “more surprising” and “neglected” works of LDS scripture.[163] With the great spate of publications over the decades since fragments of Egyptian papyri were rediscovered in the Metropolitan Museum of Art,[164] we have begun to see a remedy for the previous neglect of the book of Abraham.[165] Now, gratefully, because of wider availability of the original manuscripts and new detailed studies of their contents, the book of Moses is also beginning to receive its due.[166]

Regarding the value of the “greatness of the evidences”[167] available to enhance our study of modern scripture, Elder Jeffrey R. Holland has said:[168]

Our testimonies aren’t dependent on evidence — we still need that spiritual confirmation in the heart of which we have spoken — but not to seek for and not to acknowledge intellectual, documentable support for our belief when it is available is to needlessly limit an otherwise incomparably strong theological position and deny us a unique, persuasive vocabulary in the latter-day arena of religious investigation and sectarian debate. Thus armed with so much evidence of the kind we have celebrated here tonight, we ought to be more assertive than we sometimes are in defending our testimony of truth.

As part of a broader discussion of Mormon theology, Stephen Webb[169] concluded that Joseph Smith “knew more about theology and philosophy than it was reasonable for anyone in his position to know, as if he were dipping into the deep, collective unconsciousness of Christianity with a very long pen.” Far more significant than the astonishing discovery of ancient echoes in a work of modern revelation is that the Prophet recovered a story of Enoch the Seer that manifests a deep understanding of what it means to become a “partaker of the divine nature”[170] and in that process to become a partner with God Himself in the salvation and exaltation of His children,[171] being raised to a perspective from which we see the world through God’s eyes.

Joseph Smith yearned that Enoch’s vision of eternity might be experienced by all the Saints. The essential prerequisite is that they be filled with the same “pure love of Christ”[172] that animated the ancient seer:[173]

… let every selfish feeling be not only buried, but annihilated; and let love to God and man predominate and reign triumphant in every mind, that their hearts may become like unto Enoch’s of old, so that they may comprehend all things present, past, and future, and “come behind in no gift; waiting for the coming of the Lord Jesus Christ.”[174]

Further Study

As a first video supplement to this lesson with additional details and artwork not included in this article, see Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, “Could Joseph Smith Have Drawn on Ancient Manuscripts When He Translated the Story of Enoch?” available at The Interpreter Foundation (https://cdn.interpreterfoundation.org/ifvideo/180122-Could Joseph Smith Have Drawn on Ancient.m4v) and FairMormon (https://youtu.be/7zJwuZ_yPyY).

As a second video supplement to this lesson, see Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, “The LDS story of Enoch As a Temple Text (http://www.templestudies.org/2013-enoch-and-the-temple-conference/conference-videos/). Several other excellent video presentations on Enoch and the temple, including one by David J. Larsen discussing ancient parallels with the taking up of Enoch’s city to heaven, are available at this same link.

BYU studies published a special issue containing expanded versions of the presentations by Nickelsburg, Larsen, and Bradshaw (J. M. Bradshaw, LDS Book of Enoch; G. W. E. Nickelsburg, Temple According to 1 Enoch D. J. Larsen, Enoch and the City of Zion (2014)).

For a verse-by-verse commentary on the story of Enoch in Moses 6:13-7, see J. M. Bradshaw, et al., God’s Image 2, pp. 32-196. The book is available for purchase in print at Amazon.com and as a free pdf download at www.TempleThemes.net.

For more on the similarities between the pseudepigraphal 2 Enoch 10[175] and Nephi’s vision of the fountain of filthy water and the mists of darkness, see Book of Mormon Central KnoWhy #404, “What Does an Ancient Book About Enoch Have to Do With Lehi’s Dream?” (https://knowhy.bookofmormoncentral.org/ot-gospel-doctrine).

For a scripture roundtable video from The Interpreter Foundation on the subject of Gospel Doctrine lesson 5, see https://interpreterfoundation.org/scripture-roundtable-55-old-testament-gospel-doctrine-lesson-5-if-thou-doest-well-thou-shalt-be-accepted/.

References

Achtemeier, Paul J. 1 Peter. Hermeneia, ed. Helmut Koester, Harold W. Attridge, Adela Yarbro Collins, Eldon Jay Epp and James M. Robinson. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1996.

Alexander, P. “3 (Hebrew Apocalypse of) Enoch.” In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. 2 vols. Vol. 1, 223-315. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Alexander, Philip S. “From son of Adam to second God: Transformations of the biblical Enoch.” In Biblical Figures Outside the Bible, edited by Michael E. Stone and Theodore A. Bergren, 87-122. Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International, 1998.

Allison, Dale C., ed. Testament of Abraham. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter, 2003.

Andersen, F. I. “2 (Slavonic Apocalypse of) Enoch.” In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. 2 vols. Vol. 1, 91-221. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Anderson, Gary A. “The exaltation of Adam.” In Literature on Adam and Eve: Collected Essays, edited by Gary A. Anderson, Michael E. Stone and Johannes Tromp, 83-110. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2000.

Anderson, H. “3 Maccabees.” In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. Vol. 2, 509-29. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Bandstra, Barry L. Genesis 1-11: A Handbook on the Hebrew Text. Baylor Handbook on the Hebrew Bible, ed. W. Dennis Tucker, Jr. Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2008.

Barker, Kenneth L., ed. New International Version (NIV) Study Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2002.

Barlow, Philip L. Mormons and the Bible: The Place of the Latter-day Saints in American Religion. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1991.

———. “Decoding Mormonism.” Christian Century, 17 January 1996, 52-55.

Barney, Quinten. “Sobek: The idolatrous god of Pharaoh Amenemhet III.” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 22, no. 2 (2013): 22-27.

Beecher, Maureen Ursenbach. “The Iowa Journal of Lorenzo Snow.” BYU Studies 24, no. 3 (1984): 261-73.

Bennett, Archibald F. Saviors on Mount Zion: Course No. 21 for the Sunday School. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Sunday School Union Board, 1950.

Bloom, Harold. The American Religion: The Emergence of the Post-Christian Nation. New York City, NY: Simon and Schuster, 1992.

———. Jesus and Yahweh: The Names Divine. New York City, NY: Riverhead Books (Penguin Group), 2005.

Bowen, Matthew L. E-mail message to Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, January 23, 2018.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. Ancient and Modern Perspectives on the Book of Moses. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Publishing, 2010.

———. “The Ezekiel Mural at Dura Europos: A tangible witness of Philo’s Jewish mysteries?” BYU Studies 49, no. 1 (2010): 4-49.

———. Creation, Fall, and the Story of Adam and Eve. 2014 Updated ed. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014.

———. “The LDS book of Enoch as the culminating story of a temple text.” BYU Studies 53, no. 1 (2014): 39-73. http://www.templethemes.net/publications/140224-a-Bradshaw.pdf. (accessed September 19, 2017).

———. “Freemasonry and the Origins of Modern Temple Ordinances.” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 15 (2015): 159-237. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/freemasonry-and-the-origins-of-modern-temple-ordinances/. (accessed May 20, 2016).

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and Ronan J. Head. “The investiture panel at Mari and rituals of divine kingship in the ancient Near East.” Studies in the Bible and Antiquity 4 (2012): 1-42.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., Jacob Rennaker, and David J. Larsen. “Revisiting the forgotten voices of weeping in Moses 7: A comparison with ancient texts.” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 2 (2012): 41-71.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. “Ancient affinities within the LDS book of Enoch, Part One.” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 4 (2013): 1-27. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/ancient-affinities-within-the-lds-book-of-enoch-part-one/. (accessed May 25, 2013).

———. “Ancient affinities within the LDS book of Enoch, Part Two.” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 4 (2013): 29-74. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/ancient-affinities-within-the-lds-book-of-enoch-part-two/. (accessed May 25, 2013).

———. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014.

Brenton, Lancelot C. L. 1851. The Septuagint with Apocrypha: Greek and English. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2005.

Brooke, John L. The Refiner’s Fire: The Making of Mormon Cosmology, 1644-1844. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Brown, Francis, S. R. Driver, and Charles A. Briggs. 1906. The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2005.

Brown, Matthew B. Exploring the Connection Between Mormons and Masons. American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 2009.

Brown, S. Kent. “Man and Son of Man: Issues of theology and Christology.” In The Pearl of Great Price: Revelations from God, edited by H. Donl Peterson and Charles D. Tate, Jr., 57-72. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Religious Studies Center, 1989.

Bruno, Cheryl L. “Congruence and concatenation in Jewish mystical iiterature, American Freemasonry, and Mormon Enoch Writings.” Journal of Religion and Society 16 (2014): 1-19.

Bushman, Richard. “The Mysteries of Mormonism.” Journal of the Early Republic 15, no. 3 (Fall 1995): 501-08.

Bushman, Richard Lyman. Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling, A Cultural Biography of Mormonism’s Founder. New York City, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005.

Calabro, David. E-mail message to Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, January 24, 2018.

Cirillo, Salvatore. “Joseph Smith, Mormonism, and Enochic Tradition.” Masters Thesis, Durham University, 2010.

Clark, E. Douglas. The Blessings of Abraham: Becoming a Zion People. American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 2005.

Collins, John J. “The angelic life.” In Metamorphoses: Resurrection, Body and Transformative Practices in Early Christianity, edited by Turid Karlsen Seim and Jorunn Okland. Ekstasis: Religious Experience from Antiquity to the Middle Ages, ed. John R. Levison, 291-310. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter, 2009.

Davids, Peter H. The Letters of 2 Peter and Jude. The Pillar New Testament Commentary, ed. Donald A. Carson. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2006.

———. II Peter and Jude: A Handbook on the Greek Text. Waco, TX: Baylor University, 2011.

Dennis, Lane T., Wayne Grudem, J. I. Packer, C. John Collins, Thomas R. Schreiner, and Justin Taylor. English Standard Version (ESV) Study Bible. Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles, 2008.

Dogniez, Cécile, and Marguerite Harl, eds. Le Pentateuque d’Alexandrie: Texte Grec et Traduction. La Bible des Septante, ed. Cécile Dogniez and Marguerite Harl. Paris, France: Les Éditions du Cerf, 2001.

Draper, Richard D., S. Kent Brown, and Michael D. Rhodes. The Pearl of Great Price: A Verse-by-Verse Commentary. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005.

Eaton, John H. The Psalms: A Historical and Spiritual Commentary with an Introduction and New Translation. London, England: T&T Clark, 2003.

Elliott, Nicholas. 1988. John Bright: Voice of Victorian Liberalism. In The Freeman. http://www.fee.org/the_freeman/detail/john-bright-voice-of-victorian-liberalism – axzz2RtlkTEaO. (accessed April 29, 2013).

Etheridge, J. W., ed. The Targums of Onkelos and Jonathan Ben Uzziel on the Pentateuch, with the Fragments of the Jerusalem Targum from the Chaldee. 2 vols. London, England: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts, 1862, 1865. Reprint, Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2005. http://www.targum.info/pj/psjon.htm. (accessed August 10, 2007).

Faulring, Scott H., Kent P. Jackson, and Robert J. Matthews, eds. Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible: Original Manuscripts. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2004.

Fitzmyer, Joseph A. , ed. The Genesis Apocryphon of Qumran Cave 1 (1Q20): A Commentary Third ed. Biblica et Orientalia 18/B. Rome, Italy: Editrice Pontificio Istituto Biblico, 2004.

Fletcher-Louis, Crispin H. T. “The revelation of the sacral Son of Man: The Genre, History of Religions Context and the Meaning of the Transfiguration.” In Auferstehung — Resurrection : The Fourth Durham-Tübingen Research Symposium: The Fourth Durham-Tübingen-Symposium: Resurrection, Exaltation, and Transformation in Old Testament, Ancient Judaism, and Early Christianity (Tübingen, Germany, September 1999), edited by Friedrich Avemarie and Hermann Lichtenberger, 247-98. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr-Siebeck, 2001.

Gee, John, and Brian M. Hauglid, eds. Astronomy, Papyrus, and Covenant. Studies in the Book of Abraham 3. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS), Brigham Young University, 2005.

Gee, John, and Kerry Muhlestein. “An Egyptian context for the sacrifice of Abraham.” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 20, no. 2 (2011): 70-77.

Gee, John. An Introduction to the Book of Abraham. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2017.

Givens, Terryl L., and Fiona Givens. The God Who Weeps: How Mormonism Makes Sense of Life. Salt Lake City, UT: Ensign Peak, 2012.

Hamblin, William J., Daniel C. Peterson, and George L. Mitton. “Mormon in the fiery furnace or Loftes Tryk goes to Cambridge.” Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 6, no. 2 (1994): 3-58.

———. “Review of John L. Brooke: The Refiner’s Fire: The Making of Mormon Cosmology, 1644-1844.” BYU Studies 34, no. 4 (1994): 167-81.

Hauglid, Brian M., ed. A Textual History of the Book of Abraham: Manuscripts and Editions. Studies in the Book of Abraham 5, ed. John Gee and Brian M. Hauglid. Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute, Brigham Young University, 2010.

Hendel, Ronald S. The Text of Genesis 1-11: Textual Studies and Critical Edition. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Hess, Richard S. Studies in the Personal Names of Genesis 1-11. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2009.

Holland, Jeffrey R. 2017. The greatness of the evidence (Talk given at the Chiasmus Jubilee, Joseph Smith Building, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, 16 August 2017). In Mormon Newsroom. http://www.mormonnewsroom.org/article/transcript-elder-holland-speaks-book-of-mormon-chiasmus-conference-2017. (accessed August 18, 2017).

Howard, Richard P. Restoration Scriptures. Independence, MO: Herald House, 1969.

Jackson, Kent P. The Book of Moses and the Joseph Smith Translation Manuscripts. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Religious Studies Center, 2005. https://rsc.byu.edu/archived/book-moses-and-joseph-smith-translation-manuscripts. (accessed August 26, 2016).

Jellinek, Adolph, ed. Bet ha-Midrasch. Sammlung kleiner midraschim und vermischter Abhandlungen aus der ältern jüdischen Literatur. 6 vols. Vol. 4. Leipzig, Germany: C. W. Vollrath, 1857.

Josephus, Flavius. 37-ca. 97. “The Antiquities of the Jews.” In The Genuine Works of Flavius Josephus, the Jewish Historian. Translated from the Original Greek, according to Havercamp’s Accurate Edition. Translated by William Whiston, 23-426. London, England: W. Bowyer, 1737. Reprint, Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications, 1980.

Kee, Howard C. “Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs.” In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. Vol. 1, 775-828. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Keener, Craig S. The Gospel of John: A Commentary. 2 vols. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2003.

Koehler, Ludwig, Walter Baumgartner, Johann Jakob Stamm, M. E. J. Richardson, G. J. Jongeling-Vos, and L. J. de Regt. The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament. 4 vols. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 1994.

Larsen, David J. “Enoch and the City of Zion: Can an entire community ascend to heaven?” BYU Studies 53, no. 1 (2014): 25-37.

Martinez, Florentino Garcia. “The Book of Giants (1Q23).” In The Dead Sea Scrolls Translated: The Qumran Texts in English, edited by Florentino Garcia Martinez. 2nd ed. Translated by Wilfred G. E. Watson, 260. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1996.

———. “The Book of Giants (4Q203).” In The Dead Sea Scrolls Translated: The Qumran Texts in English, edited by Florentino Garcia Martinez. 2nd ed. Translated by Wilfred G. E. Watson, 260-61. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1996.

———. “The Book of Giants (4Q530).” In The Dead Sea Scrolls Translated: The Qumran Texts in English, edited by Florentino Garcia Martinez. 2nd ed. Translated by Wilfred G. E. Watson, 261-62. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1996.

———. “The Book of Giants (4Q531).” In The Dead Sea Scrolls Translated: The Qumran Texts in English, edited by Florentino Garcia Martinez. 2nd ed. Translated by Wilfred G. E. Watson, 262. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1996.

———. “Genesis Apocryphon (1QapGen ar).” In The Dead Sea Scrolls Translated: The Qumran Texts in English, edited by Florentino Garcia Martinez. 2nd ed. Translated by Wilfred G. E. Watson, 230-37. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1996.

Martinez, Florentino Garcia, and Eibert J. C. Tigchelaar, eds. The Dead Sea Scrolls Study Edition. 2 vols. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 1997-1998.

Matthews, Robert J. “A Plainer Translation”: Joseph Smith’s Translation of the Bible—A History and Commentary. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1975.

Maxwell, Neal A. A Wonderful Flood of Light. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1990.

McConkie, Bruce R. Doctrines of the Restoration: Sermons and Writings of Bruce R. McConkie. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1989.

McKane, William. 1994. Matthew Black. In Obituaries of Past Fellows, Royal Society of Edinburgh. http://www.royalsoced.org.uk/cms/files/fellows/obits_alpha/black_matthew.pdf. (accessed April 3, 2013).

Migne, Jacques P. “Livre d’Adam.” In Dictionnaire des Apocryphes, ou, Collection de tous les livres Apocryphes relatifs a l’Ancien et au Nouveau Testament, pour la plupart, traduits en français, pour la première fois, sur les textes originaux, enrichie de préfaces, dissertations critiques, notes historiques, bibliographiques, géographiques et théologiques, edited by Jacques P. Migne. Migne, Jacques P. ed. 2 vols. Vol. 1. Troisième et Dernière Encyclopédie Théologique 23, 1-290. Paris, France: Migne, Jacques P., 1856. http://books.google.com/books?id=daUAAAAAMAAJ. (accessed October 17, 2012).

Mika’el, Bakhayla. ca. 1400. “The book of the mysteries of the heavens and the earth.” In The Book of the Mysteries of the Heavens and the Earth and Other Works of Bakhayla Mika’el (Zosimas), edited by E. A. Wallis Budge, 1-96. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1934. Reprint, Berwick, ME: Ibis Press, 2004.

Milik, Józef Tadeusz, and Matthew Black, eds. The Books of Enoch: Aramaic Fragments from Qumran Cave 4. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press, 1976.

Mopsik, Charles, ed. Le Libre hébreu d’Hénoch ou Livre des Palais. Les Dix Paroles, ed. Charles Mopsik. Lagrasse, France: Éditions Verdier, 1989.

Morano, Enrico. 2012. New research on Mani’s Book of Giants. In.

Muhlestein, Kerry. “Egyptian papyri and the book of Abraham: A faithful, Egyptological point of view.” In No Weapon Shall Prosper: New Light on Sensitive Issues, edited by Robert L. Millet, 217-43. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Religious Studies Center, 2011.

———. “The religious and cultural background of Joseph Smith Papyrus 1.” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 22, no. 1 (2013): 20-33.

———. “Assessing the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Introduction to the Historiography of their Acquisitions, Translations, and Interpretations.” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 22 (2016): 17-49.

Neyrey, Jerome H. 2 Peter, Jude: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. The Anchor Bible 37 C, ed. William F. Albright and David Noel Freedman. New York City, NY: Doubleday, 1993.

Nibley, Hugh W. “A New Look at the Pearl of Great Price.” Improvement Era 1968-1970. Reprint, Provo, UT: FARMS, Brigham Young University, 1990.

———. “Churches in the wilderness.” In Nibley on the Timely and the Timeless, edited by Truman G. Madsen, 155-212. Salt Lake City, Utah: Bookcraft, 1978.

———. Enoch the Prophet. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 2. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986.

———. “Abraham’s temple drama.” In The Temple in Time and Eternity, edited by Donald W. Parry and Stephen D. Ricks, 1-42. Provo, UT: The Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, Brigham Young University, 1999. Reprint, Nibley, Hugh W. “Abraham’s temple drama.” In Eloquent Witness: Nibley on Himself, Others, and the Temple, edited by Stephen D. Ricks. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 17, 445-482. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2008.

———. The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment. 2nd ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005.

———. 1981. Abraham in Egypt. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 14. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2000.

———. 1986. Teachings of the Pearl of Great Price. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS), Brigham Young University, 2004.

Nibley, Hugh W., and Michael D. Rhodes. One Eternal Round. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 19. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2010.

Nickelsburg, George W. E. “Enoch, Levi, and Peter: Recipients of revelation in Upper Galilee.” Journal of Biblical Literature 100, no. 4 (December 1981): 575-600.

———, ed. 1 Enoch 1: A Commentary on the Book of 1 Enoch, Chapters 1-36; 81-108. Hermeneia: A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2001.

Nickelsburg, George W. E., and James C. VanderKam, eds. 1 Enoch 2: A Commentary on the Book of 1 Enoch, Chapters 37-82. Hermeneia: A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2012.

Nickelsburg, George W. E. “The Temple According to 1 Enoch.” BYU Studies 53, no. 1 (2014): 7-24.

Noah, Mordecai M., ed. 1840. The Book of Jasher. Translated by Moses Samuel. Salt Lake City, UT: Joseph Hyrum Parry, 1887. Reprint, New York City, NY: Cosimo Classics, 2005.

Orlov, Andrei A. “The flooded arboretums: The garden traditions in the Slavonic version of 3 Baruch and the Book of Giants.” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 65, no. 2 (April 2003): 184-201.

———. The Enoch-Metatron Tradition. Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism 107. Tübingen, Germany Mohr Siebeck, 2005.

Ostler, Blake T. Of God and Gods. Exploring Mormon Thought 3. Draper, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2008.

Packer, Boyd K. The Holy Temple. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1980.

———. “Scriptures.” Ensign 12, November 1982, 51-53.

Peters, Melvin K. H., ed. A New English Translation of the Septuagint and the Other Greek Translations Traditionally Included under that Title: Deuteronomy Provisional ed. NETS: New English Translation of the Septuagint, ed. Albert Pietersma and Benjamin Wright. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2004. http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/nets/edition/deut.pdf.

Peterson, Daniel C. “On the motif of the weeping God in Moses 7.” In Reason, Revelation, and Faith: Essays in Honor of Truman G. Madsen, edited by Donald W. Parry, Daniel C. Peterson and Stephen D. Ricks, 285-317. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2002.

Peterson, H. Donl. The Story of the Book of Abraham: Mummies, Manuscripts, and Mormonism. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1995.

Quinn, D. Michael. Early Mormonism and the Magic World View. Revised and Enlarged ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books, 1998.

Rashi. c. 1105. The Torah with Rashi’s Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated. Vol. 1: Beresheis/Genesis. Translated by Rabbi Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg. ArtScroll Series, Sapirstein Edition. Brooklyn, NY: Mesorah Publications, 1995.

Reed, Annette Yoshiko. Fallen Angels and the History of Judaism and Christianity: The Reception of Enochic Literature. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Reeves, John C. Jewish Lore in Manichaean Cosmogony: Studies in the Book of Giants Traditions. Monographs of the Hebrew Union College 14. Cincinnati, OH: Hebrew Union College Press, 1992.

Rhodes, Michael D., ed. The Hor Book of Breathings: A Translation and Commentary. Studies in the Book of Abraham 2, ed. John Gee. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, Brigham Young University, 2002.

Ricks, Stephen D. “The narrative call pattern in the prophetic commission of Enoch.” BYU Studies 26, no. 4 (1986): 97-105.

Roberts, J. J. M. 1992. “The motif of the weeping God in Jeremiah and its background in the lament tradition of the ancient Near East.” In The Bible and the Ancient Near East: Collected Essays, edited by J. J. M. Roberts, 132-42. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2002.

Rowland, Christopher, and Christopher R. A. Morray-Jones. The Mystery of God: Early Jewish Mysticism and the New Testament. Compendia Rerum Iudaicarum ad Novum Testamentum 12, ed. Pieter Willem van der Horst and Peter J. Tomson. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2009.

Sandmel, Samuel, M. Jack Suggs, and Arnold J. Tkacik. “The Wisdom of Solomon.” In The New English Bible with the Apocrypha, Oxford Study Edition, edited by Samuel Sandmel, M. Jack Suggs and Arnold J. Tkacik, 97-114. New York City, NY: Oxford University Press, 1976.

Sarna, Nahum M., ed. Genesis. The JPS Torah Commentary, ed. Nahum M. Sarna. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society, 1989.

Sherry, Thomas E. “Changing attitudes toward Joseph Smith’s translation of the Bible.” In Plain and Precious Truths Restored: The Doctrinal and Historical Significance of the Joseph Smith Translation, edited by Robert L. Millet and Robert J. Matthews, 187-226. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1995.

Shipps, Jan. Sojourner in the Promised Land: Forty Years among the Mormons. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2000.

Shoulson, Mark, ed. The Torah: Jewish and Samaritan Versions Compared: LightningSource, 2008.

Skinner, Andrew C. “Joseph Smith vindicated again: Enoch, Moses 7:48, and apocryphal sources.” In Reason, Revelation, and Faith: Essays in Honor of Truman G. Madsen, edited by Donald W. Parry, Daniel C. Peterson and Stephen D. Ricks, 365-81. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2002.

Skousen, Royal. “The earliest textual sources for Joseph Smith’s “New Translation” of the King James Bible.” The FARMS Review 17, no. 2 (2005): 451-70.

Smith, Joseph, III. “Last testimony of Sister Emma.” Saints’ Herald 26 (1879): 289-90.

Smith, Joseph, Jr. The Personal Writings of Joseph Smith. 2nd ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2002.

———, ed. 1867. The Holy Scriptures: Inspired Version. Independence, MO: Herald Publishing House, 1991.

———. 1902-1932. History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Documentary History). 7 vols. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1978.

———. 1938. Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1969.

Smith, Lucy Mack. 1853. Lucy’s Book: A Critical Edition of Lucy Mack Smith’s Family Memoir. Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books, 2001.

Smoot, Stephen O. “Council, chaos, and creation in the book of Abraham.” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 22, no. 2 (2013): 28-39.

———. “In the Land of the Chaldeans”: The Search for Abraham’s Homeland Revisited.” BYU Studies 56, no. 3 (2017): 7-37.

Smoot, Stephen O., and Quinten Barney. “The Book of the Dead as a Temple Text and the Implications for the Book of Abraham.” In The Temple: Ancient and Restored. Proceedings of the 2014 Temple on Mount Zion Symposium, edited by Stephen D. Ricks and Donald W. Parry. Temple on Mount Zion 3, 183-209. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2016.

Starr, James. 2007. “Does 2 Peter 1:4 speak of deification?” In Partakers of the Divine Nature: The History and Development of Deification in the Christian Traditions, edited by Michael J. Christensen and Jeffery A. Wittung, 81-92. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2008.

Stuckenbruck, Loren T. The Book of Giants from Qumran: Texts, Translation, and Commentary. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, 1997.

Thomas, Samuel I. The “Mysteries” of Qumran: Mystery, Secrecy, and Esotericism in the Dead Sea Scrolls. Early Judaism and its Literature 25, ed. Judith H. Newman. Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature, 2009.

Thomasson, Gordon C. “Items on Enoch — Some Notes of Personal History. Expansion of remarks given at the Conference on Enoch and the Temple, Academy for Temple Studies, Provo, Utah, 22 February 2013 (unpublished manuscript, 25 February 2013).” 2013. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EaRw40r-TfM.

———. “Email message to Jeffrey M. Bradshaw.” April 7, 2014.

Tvedtnes, John A., Brian M. Hauglid, and John Gee, eds. Traditions about the Early Life of Abraham. Studies in the Book of Abraham 1, ed. John Gee. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, Brigham Young University, 2001.

VanderKam, James C. Enoch: A Man for All Generations. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1995.

Vermes, Geza, ed. 1962. The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English Revised ed. London, England: Penguin Books, 2004.

Webb, Stephen H. Jesus Christ, Eternal God: Heavenly Flesh and the Metaphysics of Matter. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Weber, Robert, ed. Biblia Sacra Vulgata 4th ed: American Bible Society, 1990.

Wevers, John William. Notes on the Greek Text of Genesis. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1993.

Whittaker, David J. “Substituted names in the published revelations of Joseph Smith.” BYU Studies 23, no. 1 (1983): 103-12.

Wintermute, O. S. “Jubilees.” In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. Vol. 2, 35-142. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Wise, Michael, Martin Abegg, Jr., and Edward Cook, eds. The Dead Sea Scrolls: A New Translation. New York City, NY: Harper-Collins, 1996.

Woodworth, Jed L. “Extra-biblical Enoch texts in early American culture.” In Archive of Restoration Culture: Summer Fellows’ Papers 1997-1999, edited by Richard Lyman Bushman, 185-93. Provo, UT: Joseph Fielding Smith Institute for Latter-day Saint History, 2000.

Wright, Archie T. The Origin of Evil Spirits. Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 2. Reihe 198, ed. Jörg Frey. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, 2005.

Zinner, Samuel. 2013. Underemphasized Parallels between the Account of Jesus’ Baptism in the Gospel of the Hebrews/Ebionites and the Letter to the Hebrews and an Overlooked Influence from 1 Enoch 96:3: “And a Bright Light Shall Enlighten You, and the Voice of Rest You Shall Hear from Heaven”. In Dr. Samuel Zinner – World Literature. http://www.samuelzinner.com/uploads/9/1/5/0/9150250/enochgosebionites.pdf. (accessed March 6, 2013).

Zucker, Louis C. “Joseph Smith as a student of Hebrew.” Dialogue 3, no. 2 (1968): 41-55.

Endnotes

While I do not share the confidence the parallelist feels for the inaccessibility of Laurence to Joseph Smith, I do not find sharp enough similarities to support the derivatist position. The tone and weight and direction of [1 Enoch and the book of Moses] are worlds apart … The problem with the derivatist position is [that] … Laurence as source material for Joseph Smith does not make much sense if the two texts cannot agree on important issues. The texts may indeed have some similarities, but the central figures do not have the same face, do not share the same voice, and are not, therefore, the same people. In this sense, the Enoch in the book of Moses is as different from the Enoch of Laurence as he is from the Enoch in the other extra-Biblical Enochs in early American culture. Same name, different voice.

For a verse-by-verse commentary on Moses 6-7 including extensive discussion of Enoch pseudepigrapha, see J. M. Bradshaw et al., God’s Image 2, pp. 33-196. Earlier discussion of the LDS story of Enoch in light of ancient Enoch documents appeared in J. M. Bradshaw et al., Ancient Affinities 1; J. M. Bradshaw et al., Ancient Affinities 2.

A human-like earth is not a new idea. An expression of earth as human-like in an account related to Enoch and Noah together, however, is beyond parallels. This is a substantial similarity that cannot be explained away as mere coincidence. In the [book of Moses] and in [1 Enoch]: A) Enoch has a vision of the impending flood (1 Enoch 91:5; Moses 7:43); B) Enoch sees Noah and his posterity survive (1 Enoch 106:18; Moses 7:43, 52); C) Enoch knows Noah’s future through an eschatological vision directed by God (1 Enoch 106:13-18; Moses 7:44-45, 51); and, D) an anthropomorphized earth suffers only to be healed by Noah (1 Enoch 107:3; Moses 7:48-50). It is not difficult to consider that [1 Enoch] and the [book of Moses] might share the idea of Enoch and Noah having had a relationship. It is the substantial similarities of the expression of this idea that provide overwhelming cause for consideration.

The term gbryn is the Aramaic form of Hebrew gibborim (singular gibbor), a word whose customary connotation in the latter language is ‘mighty hero, warrior,’ but which in some contexts later came to be interpreted in the sense of ‘giants.’ (The term is translated seventeen times with the Greek word for “giants” in the Septuagint. (ibid., p. 134 n. 60)) … Similarly nplyn is the Aramaic form of the Hebrew np(y)lym (i.e., nephilim), an obscure designation used only three times in the Hebrew Bible. Genesis 6:4 refers to the nephilim who were on the earth as a result of the conjugal union of the [‘sons of God’ and the ‘daughters of Adam’] and further qualifies their character by terming them gibborim. Both terms are translated in [Septuagint] Genesis 6:4 by [‘giants’] and in Targum Onkelos by gbry’. Numbers 13:33 reports that gigantic nephilim were encountered by the Israelite spies in the land of Canaan, here the nephilim are associated with a (different?) tradition concerning a race of giants surviving among the indigenous ethnic groups that inhabited Canaan. A further possible reference to both the nephilim and gibborim of Genesis 6:4 occurs in Ezekiel 32:27. The surrounding pericope presents a description of slain heroes who lie in Sheol, among whom are a group termed the gibborim nophelim [sic] me’arelim. The final word, me’arelim, ‘from the uncircumcised,’ should probably be corrected on the basis of the Septuagint… to me’olam, and the whole phrase translated ‘those mighty ones who lie there from of old’…

The conjunction of gbryn wnpylyn in QG1 1:2 may be viewed as an appositional construction similar to the expression ‘yr wqdys “Watcher and Holy One” (e.g., Daniel 4:10, 14). However, the phrase might also be related to certain passages that suggest there were three distinct classes (or even generations) of Giants, names for who of which are represented in this line . … [C]ompare Jubilees 7:22: ‘And they bore children, the Naphidim [sic] … and the Giants killed the Naphil, and the Naphil killed the ‘Elyo, and the ‘Elyo [killed] human beings, and humanity [killed] one another.”

For more in-depth analysis of these terms, see A. T. Wright, Evil Spirits, pp. 79-95.

The -ah in Mahujah and Mahijah is problematic if you are interpreting the current forms of these names as equivalents of both Mahaway and also of Mehuja-/Mehija- in Mahujael/Mahijael at the same time. In other words, Mahujah can = MHWY + Jah or Mehjael can = Mahujael can = Mahujah + El, but both equations can’t be applied to the current forms of these names at the same time.

Of course, Calabro observes, the rules were different in earlier times, since “dropping of final vowels only happened sometime between 1200 and 600 BC” (ibid.):

But it’s unlikely that the names in Moses are making a point of this. Joseph left the rest of the biblical names untouched. And if Lehi, Paul, and Jude all had access to the Book of Moses (as I believe they did), the name would have dropped any final short vowels before the text was finished being transmitted. …

[I]n the Book of Mormon, the Prophet was very careful about the spelling of proper names, especially the first time they occurred. I would assume that this was the case with the book of Moses also.

That said, Calabro goes on to explain why the connections between these names are not unlikely, even in the face of these considerations (ibid.):

Very often in pseudepigraphal traditions, you get names that sound similar (or sometimes not even similar), just garbled a bit. It’s frequent in Arabic forms of biblical names: Ibrahim for “Abraham” (perhaps influenced by Elohim or some other plural Hebrew noun), ‘Isa for Yasu‘ “Jesus,” etc. So Mahujah, Mahijah, Mehujael/Mehijael, and MḤWY could all be connected, with something getting mixed up in transmission.

With respect to correspondences between Mahujah and Mahijah, H. W. Nibley, Enoch, p. 278 argues that they are variants of the same name, given that “Mehuja-el” appears in the Greek Septuagint as “Mai-el” (C. Dogniez et al., Pentateuque, Genesis 4:18, p. 145; M. K. H. Peters, Deuteronomy, Genesis 4:18, p. 8) and in the Latin Vulgate as Mawiah-el (R. Weber, Vulgata, Genesis 4:18, p. 9). Since the Greek version had no internal “Ḥ,” Nibley reasons that “Mai-” could come only from “Mahi-” (MḤY-).

J. W. Wevers likewise writes that “the Septuagint spelling of Mai-el [in Genesis 4:18] follows the Samaritan tradition [Mahi-el], with the only difference being the dropped ‘h.’ The [Mahawai] version that we see in the Book of Giants, which is probably related to Genesis 4:18, shows up in the Latin Vulgate as Maviahel is likely due to the fact that Jerome went to the Hebrew version for his translation. He didn’t use the ‘Ḥ’ either and made the ‘W’ a consonant (‘v’) instead of a vowel (‘u’) in his transliteration. This is why in the Douay-Rheims Bible (based on the Vulgate), we see the name rendered as Maviael” (J. W. Wevers, Notes, p. 62 n. 4:18). See more on Genesis 4:18 below.

Note that the grandfather of the prophet Enoch also bore a similar name to Mahawai/Mahujah: Mahalaleel (Genesis 5:12-17; 1 Chronicles 1:2; Moses 6:19-20. See also Nehemiah 11:4). As a witness of how easily such names can be confused, observe that the Greek manuscript used for Brenton’s translation of the Septuagint reads “Maleleel” for “Maiel” in Genesis 4:18 (L. C. L. Brenton, Septuagint, Genesis 4:18, p. 5).

I … think it’s interesting that JST has Mahujah instead of Mehujah, which the MT also has written as Mehijael (same w/y spelling issue as in Mahujah and Mahijah – the LXX-A, Peshitta, and Vulgate all point to Mehijael or Mahijael), I’m drawn to the idea that the name derives from ḤYY/ḤYH and means “God gives life” (L. Koehler et al., Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon, 568). However, a paronomastic connection with MḤY/MḤH (“wipe out,” “annihilate” — i.e., “blot out”) is also intriguing, especially since this name occurs in the degenerate line of Cain before the Flood (cf. the use of this verb in Genesis 6:7 and 7:4). I’m even more intrigued by a possible connection between this root and the name-title “Mahan” in “Master Mahan” which could easily be MḤN, which might suggest the idea of “destroyer” or “annihilator.”

Baraq’el appears as Virogdad (= gift of the lightning, a name recognized by Henning as having affinities to Baraq’el (J. T. Milik et al., Enoch, pp. 300, 311) in the Manichaean fragments of the Book of Giants (J. C. Reeves, Jewish Lore, p. 147 n. 202, p. 138 n. 98). According to Jubilees 4:15 (O. S. Wintermute, Jubilees, Jubilees 4:15, p. 61, see also pp. 61-62 n. g.), Baraq’el is also the father of Dinah, the wife of Enoch’s grandfather Mahalaleel. If one assumed the descriptions in the relevant accounts were consistent (no doubt a far-fetched assumption), this would make the prophet Enoch a first cousin once-removed to Mahujah.

In the Doctrine and Covenants, the name of Enoch (D&C 78, 82, 92, 96, 104) or Baraq’el (= Baurak Ale. D&C 103, 105. Note that Joseph Smith’s approach is simply to follow the lead of his Hebrew teacher, J. Seixas, who seems to have transliterated both the Hebrew letters kaph and qoph with a “k,” so it is difficult to trace what original name he is transliterating) was sometimes used as a code name for Joseph Smith (D. J. Whittaker, Substituted Names, p. 6). H. W. Nibley, Teachings of the PGP, p. 268 observes:

That Baraq’el is interesting… because[, in the Book of Giants,] Baraq’el is supposed to have been the father of [Mahujah] … A professor in Hebrew at the University of Utah said, “Well, Joseph Smith didn’t understand the word barak, meaning ‘to bless’” (L. C. Zucker, Hebrew, p. 49. William W. Phelps had suggested that “Baurak Ale” meant “God bless you.” [D. J. Whittaker, Substituted Names, p. 6]). But “Baraq’el” means the “lightning of God” (G. W. E. Nickelsburg, 1 Enoch 1, p. 180). The Doctrine and Covenants is right on target in that.

S. Cirillo, Joseph Smith., p. 111 cites the conclusion of D. M. Quinn, Magic 1998, p. 224 that the transliteration “Baurak Ale” came from a “direct reading” of Laurence’s English translation of 1 Enoch. Note, however, that Laurence’s transliteration was “Barakel” not “Baurak Ale.” If Joseph Smith simply borrowed this from Laurence, why do the transliterations not match more closely?

M. L. Bowen, January 23 2018 comments:

Regarding bārāqʾēl or bāraqʾēl, I think Baurak Ale makes for a very natural transliteration, especially if Joseph is trying to pronounce ʾēl like the beverage Ale. The other possibility would be a form of BRK (“bless”), but this is less likely since the verb only occurs as a passive participle in the Qal stem. It’s hard to come to any other conclusion than that bārāqʾēl or bāraqʾēl is the name to which Joseph has reference.

Abel-Main is the Aramaic form of Abel-Maim … (cf. 1 Kings 15:20 and its parallel in 2 Chronicles 16:4). It is modern Tel Abil, situated approximately seven kilometers west-northwest of “the waters of Dan,” at the mouth of the valley between the Lebanon range to the west and Mount Hermon, here called Senir, one of its biblical names (Deuteronomy 3:8-9; cf. Song of Solomon 4:8; Ezekiel 27:5).

For more on the history of the sacred geography of this region, see ibid., pp. 238-247.