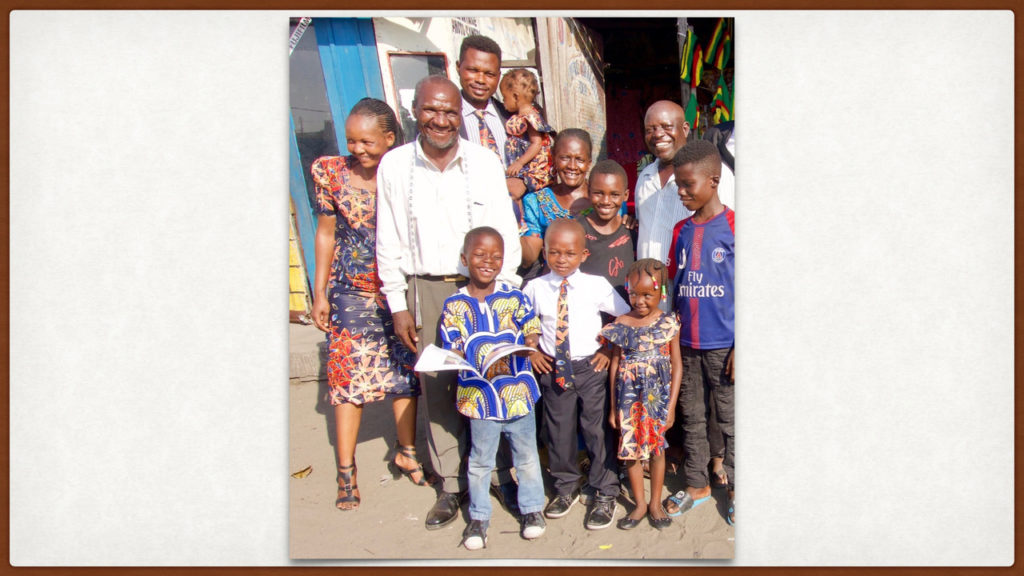

Author’s note: This series shares stories about members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Each story is framed in the context of a Christlike attribute. This article with examples of hope is an adapted and expanded from part of a presentation given at the FairMormon 2018 Conference. The video version of the entire FairMormon presentation is available on the FairMormon YouTube channel at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nJl9FvLKmjw.

As I think about the faithful Congolese Saints, I realize that what I love the most is that they take the Gospel seriously. For them, the Gospel is not simply a part of life, it is their life, their hope, and their joy.

Not long before the end of our mission, I met with a Congolese church leader who is a great example of devotion and diligence. He had scheduled another meeting later that morning. He called the Congolese brother who was in charge of this meeting to confirm the time. But the brother told my friend that he had just returned to Kinshasa by plane and for that reason had had to cancel the meeting.

After my friend hung up, he gave the situation some more thought. He realized that it couldn’t be true that this brother had just returned to Kinshasa because there were no flights that morning. He must have come back the night before. Because this brother had returned the night before there was no reason he couldn’t have been available for the meeting that morning. My friend called him again and took him to task for having canceled the meeting.

I felt compassion for the brother who had been corrected. But I also felt the power of the sincerity and earnestness with which my friend had spoken. D&C 121:43 speaks of “reproving betimes with sharpness, when moved upon by the Holy Ghost.” According to Elder H. Burke Peterson, this “means reproving with clarity, with loving firmness, with serious intent. It does not mean reproving with sarcasm, or with bitterness, or with clenched teeth and raised voice. One who reproves as the Lord has directed deals in principles, not personalities.”[2] Among other things, my friend had said in a spirit of love and inspiration, with directness and without guile: “You like to sleep too much. You cannot sleep when the work of the Lord awaits you.”

After he hung up for the second time, my friend looked me straight in the eye. He said something like this: “You can sleep, but I can’t. You have great-grandparents who were members of the Church and who gave you the rich legacy of their example and the blessings of the Gospel. But we who are of the first generations of the Church in the Congo must build this legacy for our posterity from nothing. We don’t have time to sleep.”

His words touched me deeply. I knew he had spoken truly about the urgency of the work that had to be accomplished by pioneering members of the Church in the DR Congo. But I also knew that I had no more time myself for sleep than he did. I remembered that Elder Dieter F. Uchtdorf spoke to every member of the Church when he said: “We [must] not sleep through the Restoration.” “Let us be awake and not be weary of well-doing for we ‘are laying the foundation of a great work,’ even preparing for the return of the Savior.”[3] I also remembered the words of J. Reuben Clark, a former member of the First Presidency:[4]

In living our lives let us never forget that the deeds of our fathers and mothers are theirs, not ours; that their works cannot be counted to our glory; that we can claim no excellence and no place, because of what they did, that we must rise by our own labor, and that labor failing we shall fail. We may claim no honor, no reward, no respect, nor special position or recognition, no credit because of what our fathers were or what they wrought. We stand upon our own feet in our own shoes. There is no aristocracy of birth in this Church; it belongs equally to the highest and the lowliest; for as Peter said to Cornelius, the Roman centurion, seeking him:[5]

Of a truth I perceive that God is no respecter of persons: But in every nation he that feareth him, and worketh righteousness, is accepted with him.

Traditionally, the West sent Christian missionaries to evangelize in the Global South. In 2018, should it be the other way around?”[6]

To most of us reading this article — comfortable and sometimes sleepy Saints living among long-established stakes who are accustomed to thinking of ourselves as keepers of the flame of global faith — the growing strength of the members of the Church in places like the DR Congo should provide an urgent wake-up call, encouraging us to reassess the depth of our discipleship. While the more abundant tangible resources of Western nations remain essential to the leadership and logistics of missionary operations worldwide, the spiritual vitality of the “Global South” is becoming an increasingly important dynamic in the growth and ongoing nourishment of faith among all nations.[7]

To first-world countries who have long sent missionaries to bring Christianity to “the ends of the earth,”[8] the examples of faithful members from the nations of Africa, Latin America, and Asia can serve as striking models of what Latter-day Saints worldwide are striving to become. As their growing presence in the West becomes a leavening influence in wards and stakes, the service of these “missionaries-in-reverse”[9] lifts and blesses not only those from their countries of origin,[10] but also the peoples of the “New Dark Continents” of Europe and North America.[11]

As in the days of Samuel the Lamanite — perhaps the most obvious scriptural type of a missionary-in-reverse — avoiding disaster in the crucial coming days is not so much a matter of adapting the institutional Church to a changing world (though sometimes changing policies, programs, and organizational structures can help focus our awareness and increase our collective effectiveness[12]) but ultimately will be the result of the deepened conversion of individuals and families.[13] As President Russell M. Nelson has reminded us, the salvation of the world, both individually and collectively, is a matter of “cultivat[ing our] own covenant of consecration”[14] and ministering to each other in a “higher and holier way.”[15]

May God help us to emulate the example of the faithful Congolese Saints.[16]

Thanks to Matthew K. Heiss of the global support and training division at the Church History Library for his encouragement and support in the publication of this story, and for affirming permission on behalf of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to use oral history-related material found in this series of articles.

References

Clark, J. Reuben, Jr. 1947. "To them of the last wagon (October 5, 1947)." In J. Reuben Clark: Selected Papers on Religion, Education, and Youth, edited by David H. Yarn, Jr., 67-74. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1984. Reprint, Ensign 27, July 1997, pp. 34-39.

da Silva, Oseias. "Reverse mission in the Western context." Holiness: The Journal of Wesley House Cambridge 1, no. 2 (2015): 231-44. https://www.wesley.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/06-da-silva.pdf. (accessed October 13, 2018).

Hearne, Brian. "Reverse mission: Or mission in reverse?" The Furrow 42, no. 5 (1991): 281-86. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27661975?read-now=1&loggedin=true. (accessed October 13, 2018).

"How Africa is changing the face of mission." Sedos Bulletin (https://sedosmission.org/article/how-africa-is-changing-the-face-of-mission/, accessed October 13, 2018).

Imtiaz, Saba. 2018. A new generation redefines what it means to be a missionary (8 March 2018). In The Atlantic (Global). https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/03/young-missionaries/551585/. (accessed October 13, 2018).

Killingray, David. "Passing on the Gospel: Indigenous mission in Africa (24 March 2011)." Transformation: An International Journal of Holistic Mission Studies (2011). https://doi.org/10.1177/0265378810396296. (accessed October 13, 2018).

Kim, Rebecca Y. 2015. Why are missionaries in America? In OUPblog: Oxford University Press’s Academic Insights for the Thinking World. https://blog.oup.com/2015/02/missionaries-america/. (accessed October 13, 2018).

Kim, S. Hun, and Wonsuk Ma. Korean Diaspora and Christian Mission. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2011.

Kuo, Lily. 2017. Africa’s ‘reverse missionaries’ are bringing Christianity back to the United Kingdom (11 October 2017). In QuartzAfrica (Spread the Word). https://qz.com/africa/1088489/africas-reverse-missionaries-are-trying-to-bring-christianity-back-to-the-united-kingdom/.

Nelson, Russell M. Teachings of Russell M. Nelson. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2018.

Olofinjana, Israel. Reverse in Ministry and Missions: Africans in the Dark Continent of Europe: An Historical Study of African Churches in Europe. AuthorHouse. Central Milton Keynes, UK, 2010. https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=0mqbq4290n8C&rdid=book-0mqbq4290n8C&rdot=1&source=gbs_vpt_read&pcampaignid=books_booksearch_viewport. (accessed October 13, 2018).

———. "Reverse mission: Spiritual children of Western missionaries (19 October 2013)." Mission Africanus: Journal of African Missionology in Britain (2013). https://israelolofinjana.wordpress.com/2013/10/25/reverse-mission-spiritual-children-of-western-missionaries/. (accessed October 13, 2018).

—?—. 2014. Reverse mission: A sign of arrogance or gratitude (6 May 2014). In EthicsDaily.com. https://www.ethicsdaily.com/reverse-mission-a-sign-of-arrogance-or-gratitude-cms-21774/. (accessed October 13, 2018).

Payne, J. D. 2010. Missions in reverse? (8 December 2010). In Missiologically Thinking. http://www.jdpayne.org/2010/12/missions-in-reverse/. (accessed October 13, 2018).

Peterson, H. Burke. "Unrighteous dominion." Ensign 19, July 1989, 7. https://churchofjesuschrist.org/ensign/1989/07/unrighteous-dominion?lang=eng. (accessed October 13, 2018).

Priest, Michael. 2016. On reverse mission (9 December 2016). In Local Church Global Mission. https://localchurchglobalmission.org/2016/12/09/on-reverse-mission/. (accessed October 13, 2018).

Ross, Kenneth R. . "Non-Western Christians in Scotland: Mission in reverse." Theology in Scotland 12, no. 2 (2005): 71-89. https://ojs.st-andrews.ac.uk/index.php/TIS/article/viewFile/294/287. (accessed October 13, 2018).

Uchtdorf, Dieter F. "Are you sleeping through the restoration?" Ensign 44, May 2014, 58-62.

Währisch-Oblau, Claudia. "Mission in reverse: Whose image in the mirror?" Anvil 18, no. 4 (2001): 261-67. https://biblicalstudies.org.uk/pdf/anvil/18-4_261.pdf. (accessed October 13, 2018).

Endnotes

S. Imtiaz, New Generation provides an apt summary of the current state of affairs in the perception and practice of missionary work among Christian denominations worldwide:

Christianity is shrinking and aging in the West, but it’s growing in the Global South, where most Christians are now located. With this demographic shift has come the beginning of another shift, in a practice some Christians from various denominations embrace as a theological requirement. There are hundreds of thousands of missionaries around the world, who believe scripture compels them to spread Christianity to others, but what’s changing is where they’re coming from, where they’re going, and why.

The model of an earlier era more typically involved Christian groups in Western countries sending people to evangelize in Africa or Asia. In the colonial era of the 19th and early 20th centuries in particular, missionaries from numerous countries in Europe, for example, traveled to countries like Congo and India and started to build religious infrastructures of churches, schools, and hospitals. And while many presented their work in humanitarian terms of educating local populations or assisting with disaster relief, in practice it often meant leading people away from their indigenous spiritual practices and facilitating colonial regimes in their takeover of land. Kenya’s first post-colonial president Jomo Kenyatta described the activities of British missionaries in his country this way: “When the missionaries arrived, the Africans had the land and the missionaries had the Bible. They taught us how to pray with our eyes closed. When we opened them, they had the land and we had the Bible.”

Yet as many states achieved independence from colonial powers following World War II, the numbers of Christian missionaries kept increasing. In 1970, according to the Center for the Study of Global Christianity, there were 240,000 foreign Christian missionaries worldwide. In 2000, that number had grown to 440,000. And by 2013, the center was discussing in a report the trend of “reverse mission, where younger churches in the Global South are sending missionaries to Europe,” even as the numbers being sent from the Global North were “declining significantly.” The report noted that nearly half of the top 20 mission-sending countries in 2010 were in the Global South, including Brazil, India, the Philippines, and Mexico.

As the center of gravity of mission work shifts, the profile of a typical Christian missionary is changing—and so is the definition of their mission work, which historically tended to center on the explicit goal of converting people to Christianity. While some denominations, particularly evangelicalism, continue to emphasize this, Christian missionaries nowadays are relatively less inclined to tell others about their faith by handing out translated Bibles, and more likely to show it through their work — often a tangible social project, for example in the context of a humanitarian crisis. Humanitarian work has long been part of the Christian mission experience, but it can now take precedence over the work of preaching; some missions do not involve proselytizing in any significant way. “It’s not to say that no one ever does any preaching—of course they do,” said Melani McAlister, a George Washington University professor who writes about missionaries, “but the notion that ‘our main goal is to convert people’ has been much less common among more liberal missionaries.” Instead, undertaking mission work can entail serving as a doctor, an aid worker, an English teacher, a farmer’s helper, or a pilot flying to another country to help a crew build wells. Many missionaries I’ve spoken to say they hope their actions, and not necessarily explicit words, will inspire others to join them.

“When I’m abroad I don’t use the word ‘missionary’ because of the stigma that it carries with other communities,” Jennifer Taylor, a 38-year-old missionary in Ukraine, told me recently. “I just usually use ‘volunteer’ or ‘English teacher’ so it actually sounds like I’m there with a purpose, and I’m not going to make you believe something you don’t want to believe.” She considers it her job to model a life with purpose, which she hopes can lead people to embrace Christianity without it having to be forced down their throat.

Beyond faith, Christian missionaries’ motivations can vary widely, in part because they come from diverse denominations. Mormons, Pentecostals, evangelicals, Baptists, and Catholics all do mission work. The work is particularly central to Mormonism, which encourages observation of the scriptural invocation to “preach the gospel to every creature.” Pentecostals and evangelicals are also among the more visible. (By way of comparison, at the beginning of this year, 67,000 Mormons from around the world were serving as missionaries, while the U.S.-based Southern Baptist Convention reported having sent only about 3,500 missionaries overseas.) They may be driven by their faith, the wish to do good in the world, and an interest in serving a higher purpose. But their motivations, according to young Christian missionaries I’ve spoken to, also include everything from the desire to travel abroad to the desire for social capital. Often, these are mutually reinforcing.

Faith, of course, remains a primary driver. Many feel that they’ve been “called,” that they’ve received “a transcendent summons,” said Lynette Bikos, a psychologist who has researched children in international missionary families. For some, the sense of a calling might lead to joining the Peace Corps or a non-profit, but “what distinguishes missionaries is this sense of transcendent missions; they’re doing it for religious purposes—to dig wells, but to do it in a Christian context,” Bikos said.

Among the new generation of Western Christian missionaries, the so-called “white savior complex”—a term for the mentality of relatively rich Westerners who set off to “save” people of color in poorer countries but sometimes do more harm than good—is slowly fading. “I think for many missionaries today, contrary to when I was growing up, missionary experience is primarily seen through the lens of social justice and advocacy, with proselytizing as a secondary condition,” said Mike McHargue, an author and podcaster who writes about science and faith. “I think young Christians today have experienced and internalized some critique of that colonial approach to mission work.”

Sarah Walton, a 21-year-old Mormon from Utah, went on a 19-month mission trip to Siberia when she was 19; she said her desire to go emerged from her belief in God. “I was really lucky to have the experience to go outside the United States,” she told me. “Since then I’ve become addicted to traveling and going outside the U.S.” She’s studying in Israel this year. …

Meanwhile, missionary life looks very different for people coming from outside the West. “To a surprising degree, third-world Christians, or ‘majority-world’ Christians in the language of political correctness, are not burdened by a Western guilt complex, and so they have embraced the vocation of mission as a concomitant of the gospel they have embraced: The faith they received they must in turn share,” said Lamin Sanneh, a professor of Missions and World Christianity at Yale Divinity School. “Their context is radically different from that of cradle Christians in the West. Christianity came to them while they had other equally plausible religious options. Choice rather than force defined their adoption of Christianity; often discrimination and persecution accompanied and followed that choice.”

At the Jordan Evangelical Theological Seminary in Amman, for example, two-thirds of the 150-odd student body comes from within the Middle East, according to the founder Imad Shehadeh. The curriculum focuses on understanding Arab culture, the role of Arab Christians, and how to minister in the region. The majority of the students are setting out to be church leaders, build new churches, and proselytize; students are asked to serve in Arab countries. “We had a couple go back to Aleppo” in Syria, Shehadeh said. “They’d lost everything, came here, studied here. They did so well. They returned to Aleppo—they’re leading a church there. They said, ‘We cannot go back to our countries when things are okay. We need to go back when things are tough.'” …

While mission work may have evolved in some countries and denominational groups, several organizations still offer trips to countries where proselytizing can be ethically dubious, applying religious pressure to vulnerable groups. … In Jordan, Father Rif’at Bader, the director of the Catholic Center for Studies and Media, said that missionaries can harm the image of existing Christian communities. “When the Syrian refugees came to Zaatari camp, many missionaries or evangelizers came to the camp and they were speaking frankly: ‘You want to regain your peace? Join Jesus Christ.’ These are vulnerable people. Some were trying to attract them [by offering] visas or money to change their religion.”

In some places, accusing people of performing missionary work is a way to target Christian communities. In India, for instance, Hindu right-wing activists have accused Christians of being missionaries or attempting conversions, using this as a pretext to attack Christians.

And missionaries themselves face danger in some countries. Last year, for instance, two Chinese 20-somethings reportedly working as missionaries in Pakistan were kidnapped and killed in an attack claimed by ISIS. In other cases, missionaries confront political and cultural barriers. During Walton’s mission to Siberia, Russia barred proselytizing. She and her group shifted their focus to working with local church members instead.

“We’re sending Gospel workers to the Dark Continent!”

Praise the Lord, right?! But what exactly does this seemingly simple statement mean?

Its meaning used to be plain enough. For over 200 years it meant that western churches were setting aside people, resources and prayer to send Christian missionaries to Africa, or some other continent where the Gospel was not yet known. This is still happening, and rightly so.

But we wouldn’t dare use the term “Dark Continent” for Africa, or Latin America or Asia today! The reasons are a complex mix of political correctness, delight in a mission task nearing completion and embarrassment that in the West we’re no longer feeling so ‘Enlightened’.

In fact, if you still want to hear the term “Dark Continent” used, you’ll probably have to go to a mission conference in the Global South. As mission agencies springing up south of the Equator seek mission recruits, “Dark Continent” is how they are describing Europe.

How does that make you feel? How do you feel about African Christians in Nigeria putting up a world map in a mission meeting in a church in Lagos and pointing at Europe to single it out as the spiritually most needy continent? It’s a bit shocking really, but at our most honest we’d have to agree, sadly, with that description. We’re living in the “New Dark Continent.”

However, B. Hearne, Reverse Mission, p. 285 has observed that the ignorance and inaction of the West continue to contribute to such problems:

An example that came home to me recently: BBC 2 is presenting a series of African films. Of the many missionaries I asked, only one showed any interest in this series. Similarly, how many missionaries have read the worlds of writers like Chinua Achebe, Nguiga wa Thiongo, Wole Soyinka — even among those who would flock to support Nelson Mandela or Desmond Tutu? …

Today we all eat Chinese food, Indonesian food, Japanese food, when [some decades ago] Italian food would have turned our stomachs. But our mentalities don’t seem to have changed as much as our digestive tracts. You hear people blaming Africa’s economic woes and famines on mismanagement, corruption, and incompetence. You don’t hear very much about economic colonialism, multinational firms, the abuse of labor and raw materials. Even international aid has easily become an instrument of oppression, with rival agencies competing for money and publicity, and doing very little to change the order of things.

I very much appreciate Jeff’s very insightful remarks above. My own experience among the Maori in New Zealand in 1950-52 was that they had a far greater impact on me than I ever had on them. What now stuns me is that it was 68 years after Maori had begun to become Latter-day Saints. And they mostly lived in tiny communities scattered around especially the North Island. Only two Maori had been to university. But they were truly remarkable Saints with a far greater understanding of the contents of our scriptures, and especially the Book of Mormon, than one would find along the Wasatch Front. Given the situation in which they found themselves, they faith was genuine and well worth emulating. They were aware that they had become better Maori by becoming faithful Saints, while they more than suspected that our missionaries became better Saints by having come to know them and experiencing what they call mana.

Jeff more than hints that something very much like this is going on in the Democratic Republic of Congo. I admit to being a tad bit envious of his experience, which clearly confounds the notion that our missionary endeavors are manifestations of a version of American cultural imperialism. It seem obvious that what is taking place in Africa is a truly remarkable cultural exchange where those called to serve there are being transformed by their experiences by those to whom they minister.

Dear Louis, Thank you for your very kind and eloquent comments. I am grateful that in knowing you as a friend I have been able to experience vicariously a bit of the mana that has rubbed off from the Maori Saints and thoroughly penetrated your soul.