This series is cross-posted with the permission of Book of Mormon Central

from their website at Pearl of Great Price Central

Audio Player

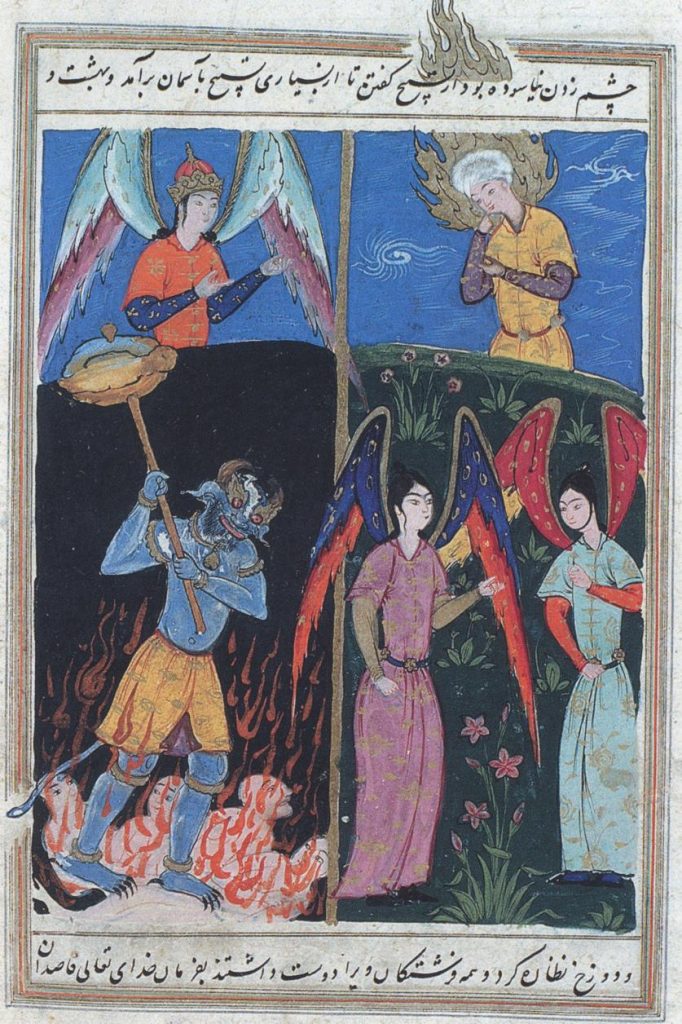

Idris [Enoch] witnessing the torments of hell. From an illustrated version of the Islamic “Tales of the Prophets” composed near the end of the 16th century.[1]

In the Book of Moses, Enoch’s reading of the book of remembrance put the people in great fear:[2]

And as Enoch spake forth the words of God, the people trembled, and could not stand in his presence.

Likewise, in the Book of Giants,[3] we read that the leaders of the mighty warriors “bowed down and wept in front of [Enoch].” 1 Enoch describes a similar reaction after Enoch finished his preaching:[4]

Then I [i.e., Enoch] went and spoke to all of them together. And they were all afraid and trembling and fear seized them. And they asked that I write a memorandum of petition[5] for them, that they might have forgiveness, and that I recite the memorandum of petition for them in the presence of the Lord of heaven. For they were no longer able to speak or to lift their eyes to heaven out of shame for the deeds through which they had sinned and for which they had been condemned.… and they were sitting and weeping at Abel-Main,[6] … covering their faces.

Conceived in Sin

Among the declarations that Joseph Smith’s Enoch makes to his hearers from the book of remembrance is that their children “are conceived in sin.”[7] Richard Draper, Kent Brown, and Michael Rhodes explain the appearance of this surprising phrase, seemingly inconsistent with the preceding verse, as follows:[8]

This statement appears to be troublesome in light of an earlier passage declaring that “children are whole from the foundation of the world.”[9] The act of conceiving between married parents is not itself sinful. Rather, it seems that because of the Fall, children come into a world saturated with sin. There is no escape. Therefore, “when they begin to grow up, sin conceiveth in their hearts.”

When verses 64 and 65 are put together, however, it becomes apparent that the tragic state of the children of Enoch’s hearers is not due simply to their fallen nature, but rather to the depth of their parents’ willfully chosen corruption. As Nibley expressed it:[10] “[T]he wicked people of Enoch’s day … did indeed conceive their children in sin, since they were illegitimate offspring of a totally amoral society.” The relevant passage in the Book of Giants reads:[11] “Let it be known to you th[at ] … your activity and (that) of [your] wive[s ] those (giants) [and their] son[s and] the [w]ives o[f ] through your fornication on the earth.”[12]

In al-Kisa’i’s version of the Islamic Tales of the Prophets, we are given further detail on the people’s wickedness:[13]

When [Enoch] was forty years old, God made him a messenger to the sons of Cain, who were giants on the earth and so preoccupied with frivolity, singing and playing musical instruments that none of them was on guard. They would gather about a woman and fornicate with her, and the devils would make their action seem good to them. They fornicated with others, daughters, and sisters, and mingled together.

A Note of Hope

Despite the rampant immorality described among their societies, both the Qumran and the Book of Moses sermons of Enoch “end on a note of hope”[14]—a feature unique to these two Enoch accounts. In the Book of Moses account, Enoch draws attention to God’s invitation of repentance that he gave to Father Adam:[15]

If thou wilt turn unto me, and hearken unto my voice, and believe, and repent of all thy transgressions … ye shall receive the gift of the Holy Ghost … and whatsoever ye shall ask, it shall be given you.

In the Book of Giants, Enoch also gives hope to the wicked through repentance:[16] “set loose what you hold captive … and pray.”[17]

Reeves[18] conjectures that another difficult-to-reconstruct phrase in the Book of Giants might also be understood as an “allusion to a probationary period for the repentance of the [gibborim].”[19] The description of a period of repentance seems to echo a specific Jewish tradition that continues to modern times. In this regard, we note Geo Widengren’s description of the Jewish tradition that “on New Year’s Day, … the judgment is carried out when three kinds of tablets are presented, one for the righteous, one for sinners, and one for those occupying an intermediate position.” [20] Widengren explains that “people of an intermediate position are granted ten days of repentance between New Year’s Day and Yom Kippurim.”[21]

Unfortunately, as we see later in the story, the initial sorrowing of the gibborim brought about only short-lived repentance for some of them. However, Matthew Goff speculates, drawing on both the Qumran and Manichaean versions of the Book of Giants that others may have repented more sincerely. He asks:[22]

Why would God give the [gibborim] a vision about the Flood in the first place? Why give them the opportunity to know about the Flood before it happens? If God’s plan is to kill them, why bother? The dreams disclosed to Ohyah and Hahyah may signify that God, by making clear to the [gibborim] what the punishment for their crimes would be, gives them the opportunity to repent. This may be a variation of the tradition often associated with the 120 years of Genesis 6:3. And, even though there is no explicit evidence for this proposal in the Qumran Book of Giants, the Manichaean Book of Giants suggests that this narrative element could have been present in the Qumran text and that the prayers of the [gibborim], in striking contrast to those of the angels in [the 1 Enoch Book of] Watchers, could have been successful.

The real hope of repentance preached by Enoch in the Book of Moses[23] and in the Book of Giants is yet another resemblance between these two texts, and a significant difference between their outlook and that of 1 Enoch.

This article was adapted and expanded from Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014, pp. 47–48.

Further Reading

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014, pp. 47–48.

Draper, Richard D., S. Kent Brown, and Michael D. Rhodes. The Pearl of Great Price: A Verse-by-Verse Commentary. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005, pp. 97–98, 101, 103.

Nibley, Hugh W. Enoch the Prophet. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 2. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986, p. 216.

References

al-Kisa’i, Muhammad ibn Abd Allah. ca. 1000-1100. Tales of the Prophets (Qisas al-anbiya). Translated by Wheeler M. Thackston, Jr. Great Books of the Islamic World, ed. Seyyed Hossein Nasr. Chicago, IL: KAZI Publications, 1997.

Draper, Richard D., S. Kent Brown, and Michael D. Rhodes. The Pearl of Great Price: A Verse-by-Verse Commentary. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005.

Etheridge, J. W., ed. The Targums of Onkelos and Jonathan Ben Uzziel on the Pentateuch, with the Fragments of the Jerusalem Targum from the Chaldee. 2 vols. London, England: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts, 1862, 1865. Reprint, Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2005. http://www.targum.info/pj/psjon.htm. (accessed August 10, 2007).

Goff, Matthew. "The sons of the Watchers in the Book of Watchers and the Qumran Book of Giants." In Ancient Tales of Giants from Qumran and Turfan: Contexts, Traditions, and Influences, edited by Matthew Goff, Loren T. Stuckenbruck and Enrico Morano. Wissenschlaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 360, ed. Jörg Frey, 115-27. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, 2016.

Kee, Howard C. "Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs." In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. Vol. 1, 775-828. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Martinez, Florentino Garcia. "The Book of Giants (4Q203)." In The Dead Sea Scrolls Translated: The Qumran Texts in English, edited by Florentino Garcia Martinez. 2nd ed. Translated by Wilfred G. E. Watson, 260-61. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1996.

———. "The Book of Giants (4Q530)." In The Dead Sea Scrolls Translated: The Qumran Texts in English, edited by Florentino Garcia Martinez. 2nd ed. Translated by Wilfred G. E. Watson, 261-62. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1996.

Milik, Józef Tadeusz, and Matthew Black, eds. The Books of Enoch: Aramaic Fragments from Qumran Cave 4. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press, 1976.

Milstein, Rachel. "The stories and their illustrations." In Stories of the Prophets: Illustrated Manuscripts of Qisas al-Anbiya, edited by Rachel Milstein, Karin Rührdanz and Barbara Schmitz. Islamic Art and Architecture Series 8, eds. Abbas Daneshvari, Robert Hillenbrand and Bernard O’Kane, 105-83. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 1999.

Milstein, Rachel, Karin Rührdanz, and Barbara Schmitz. Stories of the Prophets: Illustrated Manuscripts of Qisas al-Anbiya. Islamic Art and Architecture Series 8, ed. Abbas Daneshvari, Robert Hillenbrand and Bernard O’Kane. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 1999.

Nibley, Hugh W. "Churches in the wilderness." In Nibley on the Timely and the Timeless, edited by Truman G. Madsen, 155-212. Salt Lake City, Utah: Bookcraft, 1978.

———. Enoch the Prophet. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 2. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986.

Nickelsburg, George W. E., ed. 1 Enoch 1: A Commentary on the Book of 1 Enoch, Chapters 1-36; 81-108. Hermeneia: A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2001.

Parry, Donald W., and Emanuel Tov, eds. The Dead Sea Scrolls Reader Second ed. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2013.

Reeves, John C. Jewish Lore in Manichaean Cosmogony: Studies in the Book of Giants Traditions. Monographs of the Hebrew Union College 14. Cincinnati, OH: Hebrew Union College Press, 1992.

Reeves, John C., and Annette Yoshiko Reed. Sources from Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. 2 vols. Enoch from Antiquity to the Middle Ages 1. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Rich, Tracy R. Days of Awe. In Judaism 101. http://www.jewfaq.org/holiday3.htm. (accessed March 31, 2020.

Stuckenbruck, Loren T. The Book of Giants from Qumran: Texts, Translation, and Commentary. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, 1997.

Touger, Eliyahu. The Rambam’s Misheneh Torah. In Chabad.org. https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/682956/jewish/Mishneh-Torah.htm. (accessed March 31, 2020).

Widengren, Geo. The Ascension of the Apostle and the Heavenly Book. King and Saviour III, ed. Geo Widengren. Uppsala, Sweden: A. B. Lundequistska Bokhandeln, 1950.

Wise, Michael, Martin Abegg, Jr., and Edward Cook, eds. The Dead Sea Scrolls: A New Translation. New York City, NY: Harper-Collins, 1996.

Endnotes

Abel-Main is the Aramaic form of Abel-Maim … (cf. 1 Kings 15:20 and its parallel in 2 Chronicles 16:4). It is modern Tel Abil, situated approximately seven kilometers west-northwest of “the waters of Dan,” at the mouth of the valley between the Lebanon range to the west and Mount Hermon, here called Senir, one of its biblical names (Deuteronomy 3:8-9; cf. Song of Solomon 4:8; Ezekiel 27:5).

For more on the history of the sacred geography of this region, see ibid., pp. 238–247.

The idea continues today in what has come to be called the Yamim Noraim (Days of Awe) or Aseret Yemei Teshuvah (Ten Days of Repentance/Return). The tradition draws on Isaiah 55:6. Which says: “Seek ye the Lord while he may be found, call ye upon his name while he is near.” Maimonides formulated the most cited passages associated with this period. He wrote (E. Touger, Rambam’s Mishneh Torah, Laws of Teshuvah, 2:6):

Even though repentance and crying out to God are always timely, during the ten days from Rosh Hashanah to Yom Kippur it is exceedingly appropriate, and accepted immediately [on high].

According to T. R. Rich, Days of Awe:

One of the ongoing themes of the Days of Awe is the concept that God has “books” that he writes our names in, writing down who will live and who will die, who will have a good life and who will have a bad life, for the next year. These books are written in on Rosh Hashana, but our actions during the Days of Awe can alter God’s decree. The actions that change the decree are “teshuvah, tefilah, and tzedakah,” repentance, prayer, good deeds (usually, charity). These “books” are sealed on Yom Kippur. This concept of writing in books is the source of the common greeting during this time: “May you be inscribed and sealed for a good year.”