The account of the angels appearing to the shepherds on the night of Jesus’ birth “anesthetizes our reading by its very familiarity.”[1] Of course, no one disputes the beauty of Luke’s contrasting word pictures — shepherds in darkness met by angels in glorious light; heavenly choirs enjoining earthly worship. Yet the poetry of the account, joined as it is with the inescapable riot of images and mechanically intoned “glorias”[2] that madly engulf us each Christmas season, inevitably dims in personal significance as it increases in ubiquity. In contemporary culture, the narrative of the angels has become a pretty story[3] — and, sadly, little else.

For ancient readers of the Bible, however, the story of the shepherds was an extraordinary tale, a thinning of the veil like no other. Though the “appearance of angels is by no means frequent in the Gospels,” the first two chapters of Luke are a “remarkable outcrop”[4] of divine visitations, with annunciations to Zacharias and Mary as prelude to the most stunning angelophany recorded in scripture.

Figure 1. Watchtower, Shepherd’s Fields, Bethlehem, ca. 1934

Ancient readers recognized the deep connections in Luke’s account with Old Testament teachings and related traditions. For example Migdal Eder, the “Tower of the Flock,” the place where the angels appeared and where the sheep to be sacrificed in Jerusalem were born and raised,[5] was seen in a Jewish targum as “the place from which the King Messiah will reveal himself at the end of days.”[6] To Luke’s contemporaries, this location would have brought to mind the symbolism of the temple. Margaret Barker explains:

The Tower of the Flock … was not only a place near Bethlehem. It was an ancient name for the Holy of Holies, the place where the Lord of the sheep stood, and where His prophets received revelations.[7] Details about the tower and the flock are found in 1 Enoch, where the history of Israel is the story of the flock and of the Lord of the sheep, who leaves his tower when the flock forsake him. The Lord allowed other angel shepherds to rule them (that is, foreign rulers), but an angel scribe kept a record of their deeds and begged the Lord to intervene.[8] A birth among the shepherds outside Jerusalem but near the “Tower of the Flock” was a sign pointing to the birth in the original tower of the flock among the shepherds, in the Holy of Holies among the angels. The angel announced to the Bethlehem shepherds the birth of the Davidic king, in other words, the return of the Lord to His people in time of danger. Origen knew that the shepherds represented the guardian angels ‘keeping watch over their flocks by night,’ and that the angel of the Lord had announced the coming of the good shepherd to help them in their struggle. … [9] Since the royal child was born in the Holy of Holies, he would have emerged into the world through the temple veil, and so Luke described how the heavens opened at that point. This was all God’s angels worshipping the Firstborn as he came into the world.[10]

Figure 2. John Russell (1745–1806): Portrait of Charles Wesley (1707–1788), 1773

Charles Wesley’s Shepherd Carol

Resonating with the temple themes in Luke’s verses is the most theologically laden shepherd carol in our Christmas repertoire: Charles Wesley’s magnificent anthem “Hark! the Herald Angels Sing”[11] The hymn is given in its entirety below. The italics show verses that are omitted or altered in our current Latter-day Saint hymnbook:[12]

1. Hark how all the Welkin rings[13]

“Glory to the King of Kings[14]

Peace on earth, and mercy mild

God and sinners reconciled!”2. Joyful, all ye nations rise;

Join the triumph of the skies;

Universal nature say

Christ the Lord is born today![15]3. Christ, by highest heav’n adored;

Christ, the everlasting Lord.

Late in time behold Him come,

Offspring of a virgin’s womb.4. Veiled in flesh the Godhead see!

Hail th’Incarnate Deity!

Pleased as man with men t’appear

Jesus, our Immanuel here![16]5. Hail the Heav’nly Prince of Peace![17]

Hail the Sun of Righteousness!

Light and life to all he brings,

Ris’n with healing in His wings.[18]6. Mild He lays His glory by,

Born that man no more may die;

Born to raise the sons of earth,

Born to give them second birth.7. Come, Desire of Nations, come,

Fix us in Thy humble home.

Rise, the Woman’s Conqu’ring Seed,

Bruise in us the Serpent’s head.8. Now display thy saving pow’r,

Ruined nature now restore;

Now in mystic union join

Thine to ours, and ours to Thine.[19]9, Adam’s likeness, Lord, efface,

Stamp Thy Image in its place.

Second Adam from above,

Reinstate us in Thy love.10. Let us Thee, though lost, regain,

Thee, the Life, the Heav’nly Man:

O, to all Thyself impart,

Formed in each believing heart.

A brief review of a small sampling of lines from Wesley’s Christmas masterpiece reveals a surprising number of ideas that can be related to temple themes.

Figure 3. Gustave Doré, 1832–1883: The Empyrean (The Highest Heaven) or The White Rose, 1857. Illustration for Paradiso Canto 31:1–8, Divine Comedy (1308–1321) by Dante Alighieri.

“Join the Triumph of the Skies”

In ancient literature, heavenly worship is always described as taking a circular form. For example, in Abraham 3:23, God is described as standing “in the midst” (i.e., “in the center”) of the premortal souls.[20] Hugh Nibley clarifies this description by observing that: “He’s surrounded on all sides.”[21] Likewise, Lehi describes God upon his throne “surrounded with numberless concourses of angels in the attitude of singing and praising their God.”[22] Nibley again points out: “A concourse is a circle. Of course [numberless] concourses means circles within circles.”[23]

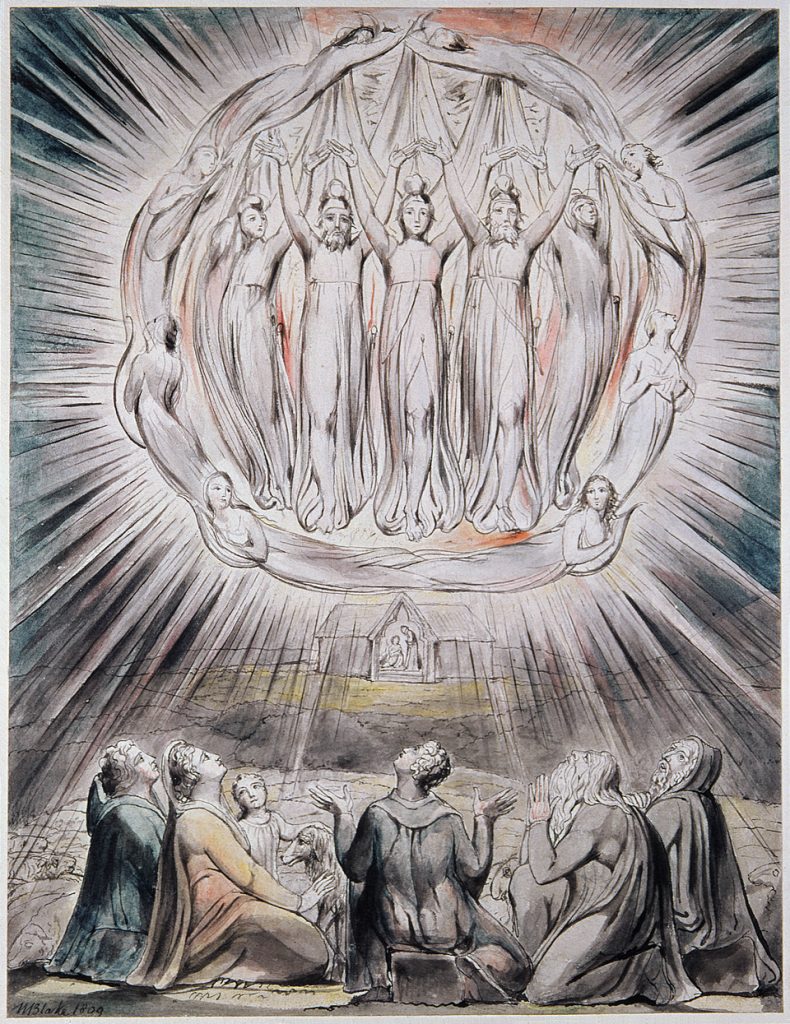

Figure 4. William Blake, 1758–1827: The Annunciation to the Shepherds, 1809

Traditional angel carols highlight the remembrance of how heaven and earth joined in the worship of the Savior.[24] “Saints and angels sing”[25] their “glorias” with one voice, echoing both the symbolism of ancient temple prayer circles and also of later Jewish prayer teachings relating to the minyan. Kogan writes:

On one level, the body that is formed below, the actual minyan [i.e., a quorum of ten men required for public prayer], is entered by the Shekhinah (the supernal holiness), and is thus the point of contact between God and Israel. Simultaneously, the minyan formed in the proper manner below unifies the heavenly realm above.[26]

Figure 5. Cave of the Nativity, Church of the Nativity, Bethlehem, 2014

While modern readers easily miss the temple symbolism in the account of the joint praise of the angels and the shepherds, the author of the Arabic Infancy Narrative[27] did not, noting that when the shepherds came to worship:

the cave [of the Nativity at Bethlehem] was at that time made like a temple of the upper world, since both heavenly and earthly voices glorified and magnified God on account of the birth of the Lord Christ.

Figure 6. Adam Enthroned, the Angels Prostrating Themselves Before Him, 1576

“Christ by Highest Heav’n Adored”

In Jewish midrash, angels are sometimes summoned “to gaze upon righteous individuals.”[28] One such tradition is connected with Adam’s ongoing rivalry with the Devil. This rivalry is said to have begun at the time the newly-created Adam was presented to the hosts of heaven, when Satan refused to pay him homage. As depicted above, an Islamic version of the story “says that seven days after Adam’s creation, God sent from Paradise a throne of red gold studded with pearls, silk cloths, and a crown. Seven hundred angels who were with Iblis [the Devil, who at that time was their leader,] arranged themselves in rows, a circle within a circle around Adam. His throne was placed where the Ka’bah is now,”[29] immediately adjacent to the Tree of Life.[30]

The original setting of Deuteronomy 32:43 (“Rejoice with him heavens, bow down to him, sons of God. Rejoice with his people, nations, confirm him all you angels of God, because he will avenge the blood of his sons”[31]) clearly refers to Jehovah rather than to Adam,[32] and its application in Hebrews 1:6 is to show the superiority of the embodied Jehovah, Jesus Christ, to the angels. F. F. Bruce concludes that the occasion referred to by the phrase “when he bringeth in the first begotten into the world” is “probably neither the incarnation nor the second advent of Christ: it is not so much a question of His being brought into the world as of his being introduced to it as the Son of God, and we may think rather of His exaltation and enthronement as sovereign over the inhabited universe, … including the realm of angels, who accordingly are summoned to acknowledge their Lord.”[33] Hence, Hebrews 1:6 can be seen as a Messianic parallel to accounts of Adam’s premortal exaltation and enthronement.

Figure 7. Master of Erfurt: The Virgin Weaving, Upper Rhine, ca. 1400

“Veiled in Flesh”

In early Christian tradition, Eve and Mary are often associated with the imagery of weaving, since it is due to the former that garments of flesh are “woven” for each child, and through the birth of Christ from the latter that the effects of the Fall were undone — thus eventually enabling mankind’s garments of flesh to be replaced with robes of glory. Moreover, in the apocryphal infancy gospels of James and Matthew, the young Mary is portrayed more specifically as weaving the new veil for the Jerusalem temple prior to the annunciation,[34] consistent with symbolism that identifies the veil of the temple as the flesh of Jesus Christ.[35]

Figure 8. Andrei Rublev, ca. 1360–1427: The Holy Trinity (detail), ca. 1408–1425

Wesley’s hymn also includes the concept of Jesus, the “second Adam,” being “veiled in flesh.”[36] In ancient depictions, Christ is often portrayed in a blue robe that represents the flesh that he put on over his robe of glory. By way of contrast, righteous individuals are sometimes depicted as wearing the blue robe of mortality underneath, with a robe of glory worn over it.

“Born to Give Them Second Birth”

Truman G. Madsen explains the significance of the “second birth” in Latter-day Saint theology: “As spirits, we are born of heavenly parentage. In the quickening processes of the temple we become Christ’s — in mind, spirit, and body. Thus, when Joseph Smith first sent the Twelve to England he instructed them to teach: ‘Being born again, comes by the Spirit of God through ordinances.’”[37]

Speaking of Christ as the prototype for all those who receive these ordinances, the Gospel of Philip expresses the same concept: “He who … [was begotten] before everything was begotten anew. He [who was] once [anointed] was anointed anew. He who was redeemed in turn redeemed (others).”[38]

Figure 9. Protoevangelium

“Rise, the Woman’s Conqu’ring Seed”

The idea behind this line can be found in Moses 4:21, where it is explained that although the serpent (Satan), in its weakened condition, may tempt and torment man, his power will ultimately be destroyed by the seed of the woman (Christ). Historically, Christians have called this prophecy the protoevangelium, the first explicit Biblical allusion to the good news of the Gospel.

Just as Jesus Christ will put all enemies beneath his feet,[39] so the Prophet Joseph Smith taught that each person who would be saved must also, with His help, gain the power needed to “triumph over all [their] enemies and put them under [their] feet,”[40] possessing the “glory, authority, majesty, power and dominion which Jehovah possesses.”[41]

Figure 10. Early Christian Painting of a Baptism, Saint Calixte Catacomb, 3rd century CE

At least one Christian account tells of how those who were about to be baptized “stood [barefoot] on animal skins while they prayed, symbolizing the taking off of the garments of skin they had inherited from Adam”[42] as well as figuratively enacting the putting off the serpent, the representative of death and sin, under one’s heel.[43] Thus the serpent, his head crushed by the heel of the penitent relying on the mercies of Christ’s atonement, is by a single act renounced, defeated, and banished.[44]

Figure 11. William Blake, 1757–1827: The Lord Answers Job from the Whirlwind, 1826

“Now in Mystic Union Join”

William Blake’s depiction shows God surrounded by a concourse of angels. Job looks up to converse with God face to face, while his friends lie prostrate in terror.[45] In other versions of this drawing, Job is caught up with God in the circle, their identical faces mirroring one other in serene mutual regard. According to Fisch, the key to understanding the illustration is that “Man is about to take on the nature of God.”[46]

Wesley’s hymn entreats Christ to join with each person “in mystic union” so that Father “Adam’s likeness” in them may be replaced by the image of Christ, the “Second Adam.” Though the concept of sealing in our day is most strongly associated with the meaning of an eternal “binding” to God and to family, Luke Timothy Johnson reminds us of the additional New Testament idea of sealing as an “imprinting” process, “from the ancient imagery of the seal, which shows identity.”[47] Thus the process of spiritual rebirth is described by Wesley as one in which the old sinful image is “effaced” and the new divine image is “stamp[ed] … in its place.” This idea is preserved in the Book of Mormon, where the Saints are asked: “Have ye spiritually been born of God? Have ye received his image in your countenances?”

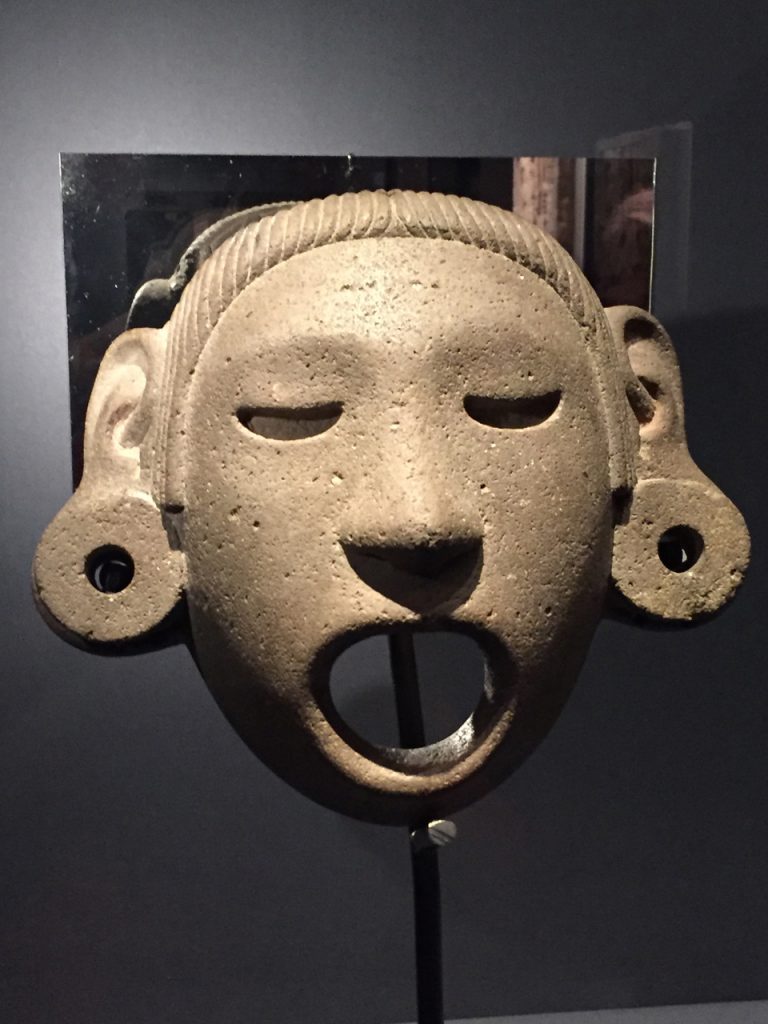

Figure 12. Deity mask of Xipe Totec (c 1400-1521, Mexico) from the British Museum

As a possible resonance with Alma’s question, Brant Gardner and Mark Wright cite the fact that “many Mesoamerican cultures participated in rituals of deity impersonation, where ‘a ritual specialist, typically the ruler, puts on an engraved mask or elaborate headdress and transforms himself into the god whose mask or headdress is being worn.’”[48]

Figure 13. Detail from the Robail-Navier Family Sepulchre, Cimitière de la Madeleine, Amiens, France, ca. 1832

Prior to the sealing of Benjamin F. Johnson to his wife, the Prophet Joseph Smith explained that “there were two seals in the Priesthood. The first was that which was placed upon a man and a woman when they made the [marriage] covenant and the other was the seal which allotted to them their particular mansion.”[49] The idea of sealing, as a confirmation, guarantee, or authentication of divine blessings in time and eternity,[50] is not bestowed simply by the act of participating in certain ritual actions, but must also include the process of one’s gradually becoming more Christlike.[51] Hugh Nibley explains that the saving ordinances, as necessary as they are, in and of themselves “are mere forms. They do not exalt us; they merely prepare us to be ready in case we ever become eligible,”[52] having finally, in the words of Joseph Smith, “attain[ed] to the image, glory, and character of God.”[53]

Figure 14. Illuminated Candles Shine in Darkness

“Such a Light”

The events of Christmas night are beautifully captured in the text of Ursula Vaughan Williams:[54]

Promise fills the sky with light,

Stars and angels dance in flight;

Joy of heav’n shall now unbind

Chains of evil from mankind,

Love and joy their power shall break,

And for a newborn prince’s sake;

Never since the world began

Such a light such dark did span.

The formidable breach of the great span that separates man from God is bridged by the joining of Christ’s condescending downward reach with man’s upward grasp. No greater evidence could be given of Heaven’s “good will toward men.”[55] “Wherefore, may the kingdom of God go forth, that the kingdom of heaven may come, that thou, O God, mayest be glorified in heaven so on earth”[56] and the final reign of the King of Kings[57] begin.

Notes on Figures

Figure 1. https://olivetreealliance.org/2018/12/12/pinpointing-messiahs-nativity-micahs-prophecy/watchtower-shepherds-fields-bethlehem-circa-1934/ (accessed December 4, 2020). Public domain.

Figure 2. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Charles_Wesley.jpg (accessed December 4, 2020). Public domain.

Figure 3. See D. Alighieri, La Divina commedia, p. 661. Cf. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/8799/8799-h/images/31-1.jpg (accessed December, 4, 2020). Public domain. For more detailed explanation of this figure, see J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, Figure 4-4, p. 219.

Figure 4. Illustration for John Milton’s “On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity” from the Thomas set. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/75/Onthemorningthomas2.jpg (accessed December 4, 2020). Public domain.

Figure 5. Photograph © Jeffrey M. Bradshaw. Image ID: DSC00534.jpg (6 May 2014).

Figure 6. With the kind permission of Rachel Milstein. From R. Milstein, et al., Stories. Original in Topkapi Saray Museum Library, H. 1227: Ms. T-7, Istanbul, Turkey. For more detailed explanation of this figure, see J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, Figure 4-7, p. 225.

Figure 7. https://sv.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fil:Master_of_Erfurt,_The_Virgin_Weaving,_Upper_Rhine,_ca_1400_(Berlin).jpg (accessed December 4, 2020). Public domain.

Figure 8. Art Resource, Inc., with the assistance of Tricia Smith. In L. Ouspensky, et al., Icons, p. 198. For more detailed explanation of this figure, see J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, Figure 5-10, p. 340.

Figure 9. https://krausekorner.wordpress.com/tag/protoevangelium/ (accessed December 4, 2020).

Figure 10. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/ commons/0/0a/Baptism_-_Saint_Calixte.jpg (accessed September 11, 2016). No known copyright restrictions. This work may be in the public domain in the United States.

Figure 11. National Galleries of Scotland Picture Library, with the assistance of Rachel Travers. For more detailed explanation of this figure, see J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, Figure E2-1, p. 517.

Figure 12. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Deity_mask_of_Xipe_Totec_(c_1400–1521,_Mexico)_from_the_British_Museum_collection,_National_Museum_of_Singapore_-_20160214.jpg (accessed December 4, 2020).Public domain. Published in Why Did Alma Ask about Having God’s Image Engraven upon One’s Countenance? (KnoWhy #295, 3 April 2017), Why Did Alma Ask.

Figure 13. Cimitière de la Madeleine, Amiens, France, ca. 1832. Photograph DSC00198, 14 September 2009, © Jeffrey M. Bradshaw.

Figure 14. https://www.dreamstime.com/photos-images/nlight.html (accessed December 4, 2020).

References

Alighieri, Dante. La Divina commedia di Dante Alighieri, illustrata da G. Doré e dichiarata con note tratte dai migliori commenti per cura di Eugenio Camerini. Milan, Italy: Società editrici Sonzogno, 1900. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/102743751. (accessed 4 December 2020).

Anderson, Gary A. The Genesis of Perfection: Adam and Eve in Jewish and Christian Imagination. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001.

Barker, Margaret. The Hidden Tradition of the Kingdom of God. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), 2007.

———. Christmas: The Original Story. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 2008.

Beale, Gregory K., and Donald A. Carson, eds. Commentary on the New Testament Use of the Old Testament. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2007.

Bickmore, Barry Robert. Restoring the Ancient Church: Joseph Smith and Early Christianity. Ben Lomond, CA: Foundation for Apologetic Information and Research (FAIR), 1999.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. In God’s Image and Likeness: Ancient and Modern Perspectives on the Book of Moses. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Publishing, 2010.

———. Creation, Fall, and the Story of Adam and Eve. 2014 Updated ed. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014. https://archive.org/details/140123IGIL12014ReadingS.

Brown, Raymond E. The Birth of the Messiah. 2nd ed. The Anchor Bible Reference Library, ed. David Noel Freedman. Doubleday: New York, NY, 1993.

Bruce, F. F., ed. The Epistle to the Hebrews Revised ed. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1990.

Chesterton, Gilbert Keith. 1910. William Blake. New York City, NY: Cosimo, 2005.

Clancy, Ronald M. Best-Loved Christmas Carols: The Stories Behind Twenty-five Yuletide Favorites. New York City, NY: Sterling Publishing, 2006.

Clayton, William. Intimate Chronicle: The Journals of William Clayton. Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books, 1995.

Cook, Lyndon W. Nauvoo Marriages Proxy Sealings 1843-1846. Provo, UT: Grandin Book Company, 2004.

Cooper, Rex Eugene. Promises Made to the Fathers. Publications in Mormon Studies 5, ed. Linda King Newell. Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press, 1990.

Dahl, Larry E., and Charles D. Tate, Jr., eds. The Lectures on Faith in Historical Perspective. Religious Studies Specialized Monograph Series 15. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1990.

Dart, John. Decoding Mark. Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International, 2003.

Elliott, J. K., ed. A Synopsis of the Apocryphal Nativity and Infancy Narratives. New Testament Tools and Studies 34, ed.Bruce M. Metzger and Bart D. Ehrman. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2006.

Faulconer, James E. "Adam and Eve—Community: Reading Genesis 2-3." Journal of Philosophy and Scripture 1, no. 1 (Fall 2003). http://www.philosophyandscripture.org/Issue1-1/James_Faulconer/james_faulconer.html. (accessed August 10).

Fawcett, Thomas. Hebrew Myth and Christian Gospel. London, England: SCM Press, 1973.

Fisch, Harold. The Biblical Presence in Shakespeare, Milton, and Blake: A Comparative Study. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press, 1999.

Gardner, Brant A., and Mark Alan Wright. "The cultural context of Nephite apostasy." Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 1 (2012): 25–55. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/the-cultural-context-of-nephite-apostasy/. (accessed December 4, 2020).

Gaskill, Alonzo L. The Lost Language of Symbolism: An Essential Guide for Recognizing and Interpreting Symbols of the Gospel. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2003.

Hamilton, Victor P. The Book of Genesis: Chapters 1-17. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1990.

Haymond, Bryce. 2009. Who were the shepherds in the Christmas story? (19 December 2009). In Temple Studies. http://www.templestudy.com/. (accessed 21 December, 2009).

Huchel, Frederick M. The Cosmic Ring Dance of the Angels: An Early Christian Rite of the Temple. North Logan, UT: The Frithurex Press, 2009. http://www.lulu.com/content/paperback-book/the-cosmic-ring-dance-of-the-angels—softbound/7409216. (accessed September 21).

———. "The cosmic ring dance of the angels: An early Christian rite of the temple." Presented at the The Temple Studies Group Symposium II, Temple Church, London England, May 30, 2009. http://www.heavenlyascents.com/2009/06/10/the-cosmic-ring-dance-of-the-angels-the-text-of-frederick-m-huchels-presentation-at-the-uk-temple-studies-group-symposium-ii/. (accessed June 11).

Hymns of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1985.

Isenberg, Wesley W. "The Gospel of Philip (II, 3)." In The Nag Hammadi Library, edited by James M. Robinson. 3rd, Completely Revised ed, 139-60. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, 1990.

Johnson, Luke Timothy. Religious Experience in Earliest Christianity: A Missing Dimension in New Testament Studies. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1998.

Keyte, Hugh, and Andrew Parrott. The New Oxford Book of Carols. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Koester, Helmut, and Thomas O. Lambdin. "The Gospel of Thomas (II, 2)." In The Nag Hammadi Library in English, edited by James M. Robinson. 3rd, Completely Revised ed, 124-38. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, 1990.

Larsen, David J. "Email message to Jeffrey M. Bradshaw." December 18, 2009.

Madsen, Truman G., and Ann N. Madsen. 1998. "House of glory, house of light, house of love." In The Temple: Where Heaven Meets Earth, 44-76. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2008.

Maher, Michael, ed. Targum Pseudo-Jonathan, Genesis. Vol. 1b. Aramaic Bible. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1992.

Milstein, Rachel, Karin Rührdanz, and Barbara Schmitz. Stories of the Prophets: Illustrated Manuscripts of Qisas al-Anbiya. Islamic Art and Architecture Series 8, ed. Abbas Daneshvari, Robert Hillenbrand and Bernard O’Kane. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 1999.

Nibley, Hugh W. 1975. "The meaning of the temple." In Temple and Cosmos: Beyond This Ignorant Present, edited by Don E. Norton. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 12, 1-41. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1992.

———. 1986. Teachings of the Pearl of Great Price. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS), Brigham Young University, 2004.

Nickelsburg, George W. E., and James C. VanderKam, eds. 1 Enoch: A New Translation. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2004.

Oaks, Dallin H. "The challenge to become." Ensign 30, November 2000, 32-34.

Ouspensky, Leonid, and Vladimir Lossky. The Meaning of Icons. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1999.

Ricks, Brian W. "James E. Talmage and the Nature of the Godhead: The Gradual Unfolding of Latter-day Saint Theology." Master’s Thesis, Brigham Young University, 2007.

Rowland, Christopher. "Things into which angels long to look: Approaching mysticism from the perspective of the New Testament and the Jewish apocalypses." In The Mystery of God: Early Jewish Mysticism and the New Testament, edited by Christopher Rowland and Christopher R. A. Morray-Jones. Compendia Rerum Iudaicarum ad Novum Testamentum 12, eds. Pieter Willem van der Horst and Peter J. Tomson, 99-136. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2009.

Sayre, Eleanor, ed. A Christmas Book: Fifty Carols and Poems from the 14th to the 17th Centuries. New York City, NY: Clarkson N. Potter, 1966.

Smith, Joseph, Jr. The Words of Joseph Smith. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1980. https://rsc.byu.edu/archived/words-joseph-smith-contemporary-accounts-nauvoo-discourses-prophet-joseph/1843/21-may-1843. (accessed February 6, 2016).

———. 1938. Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1969.

Tvedtnes, John A. "Email message." December 18, 2009.

Vaughan Williams, Ursula. "Chorale from Ralph Vaughan Williams’ ‘Hodie’: No Sad Thought His Soul Affright, second verse." 1954.

Wesley, John, and Charles Wesley. Hymns and Sacred Poems. Fourth ed. Bristol, England: Felix Farley, 1743. http://ia340912.us.archive.org/2/items/hymnsandsacredpo00wesliala/hymnsandsacredpo00wesliala.pdf. (accessed May 2).

Why Did Alma Ask about Having God’s Image Engraven upon One’s Countenance? (KnoWhy #295, 3 April 2017). 2017. In Book of Mormon Central. https://knowhy.bookofmormoncentral.org/knowhy/why-did-alma-ask-about-having-gods-image-engraven-upon-ones-countenance#footnote3_3bisktw. (accessed December 4, 2020).

Williams, Wesley. 2005. The Shadow of God: Speculations on the Body Divine in Jewish Esoteric Tradition. In The Black God. http://www.theblackgod.com/Shadow%20of%20God%20Short%5B1%5D.pdf. (accessed December 21, 2007).

Endnotes

One of the towns located near Bethlehem was Migdal-Eder, ‘tower of the flock’ (Micah 4:8), where Jacob is said to have pitched his tent after the death of his wife, Rachel, whose name means “ewe,” a female sheep (Genesis 35:19-21). It was known as the place where the lambs used for temple sacrifices were born and is mentioned in early Jewish texts. Both the Mishnah (Shekalim 7:4) and the Talmud (Kiddushin 55a) ordained that a sheep or goat found between Jerusalem and Migdal-Eder should be a burnt offering (if a male) or a peace offering (if a female), but if found during the thirty days before Passover, it could be a Passover offering if it met all other requirements for that sacrifice.

St. Jerome wrote to Eustochium of “the tower of Edar, that is “of the flock,” near which Jacob fed his flocks, and where the shepherds keeping watch by night were privileged to hear the words: “Glory to God in the highest and on earth peace, goodwill toward men.” While they were keeping their sheep they found the Lamb of God whose fleece bright and clean was made wet with the dew of heaven when it was dry upon all the earth beside, and whose blood when sprinkled on the doorposts drove off the destroyer of Egypt and took away the sins of the world” (Letter 108 to Eustochium 10).

In medieval times, Migdal-Eder was considered to be the spot where the angels appeared to the shepherds to announce the birth of Christ, and, according to Gaulish Bishop Arculf, who visited the site ca. AD 700, a church stood there with monuments to the three shepherds.

The music comes from a piece Felix Mendelssohn was commissioned to write for the Gutenberg Festival in 1840. The words for bars 9-12 originally read: “Gutenberg! du deutscher Mann!” (H. Keyte et al., New Oxford, pp. 328-329). “The German composer thought the tune had potential as a military or national song, but wrote that ‘it will never do to sacred words … the words must express something gay and popular, as the music tries to do’” (R. M. Clancy, Best-Loved, p. 59).

John Wesley … resented any modification of his or his brother’s hymns, and fulminated against the practice in his preface to the 1779 edition of A Collection of Hymns for the use of the people called Methodists: “Many Gentlemen have done to my Brother and me (though without naming us) the honor to reprint many of our hymns. Now they are perfectly welcome to do so, provided they print them just as they are. But I desire they would not attempt to mend them—for they really are not able.” He goes on to suggest that the original texts be printed in the margin, “that we may no longer be held responsible either for the nonsense or the doggerel of other men.”

Fawcett also notes the Creation and temple symbolism in Luke’s account of Christ’s conception: “The reference to Mary being overshadowed by the power of the Holy Ghost takes us back to the same source. The word was used in connection with the cloud of the tabernacle in the LXX of Exodus 40:35, and this is echoed in its use in the story of the transfiguration (Matthew 17:5). It may be explained, therefore, simply as indication of the presence of God against this background. … Yet there may be more to the use of ‘overshadow’ than a reference to God’s protective presence. We may probably see [a] reference to the imagery of the bird in Genesis 1:2” (T. Fawcett, Hebrew Myth, pp. 145-146).

Fantastic