An Old Testament KnoWhy[1]

Gospel Doctrine Lesson 10:

Birthright Blessings; Marriage in the Covenant

(Genesis 24-29) (JBOTL10A)

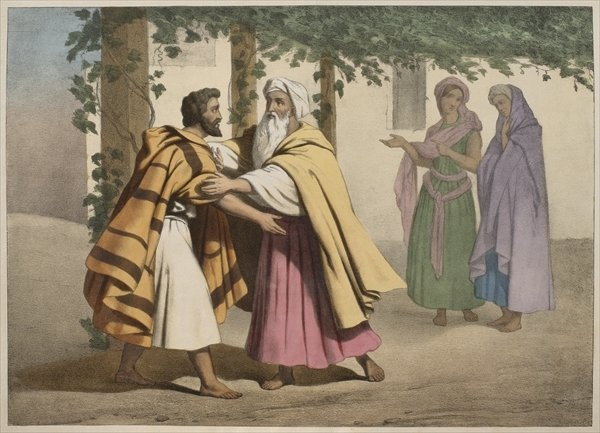

Figure 1. Francesco Hayez (1791-1881): Meeting of Esau and Jacob, 1844

Question: Why is Jacob so greatly blessed when “the pivotal moments in the scriptural account of [his] life seem to turn on deceit”?[2]

Summary: Jacob’s youthful deceits are proverbial. Indeed, the Savior Himself praised Nathanael by contrasting him with Jacob, saying, “Behold an Israelite [i.e., descendant of Jacob] indeed, in whom[, unlike his forefather, there] is no guile!”[3] However, as in all scripture stories (as in life), we cannot fully understand the lessons of Jacob’s divine tutorial unless we follow it to its end. In the Bible’s version of measure-for-measure justice, the deceiver will be himself deceived. Eventually, among the happy results of Jacob’s crucible of experience, he will learn humility, forgiveness, and that God has His own ways to fulfill His own promises.

The Know

Figure 2. Jacob and Esau

The extent of Jacob’s ambition is illustrated when we read that he struggled in the womb with his twin brother Esau by grabbing his heel.[4] By this, his original name Ya-akov-’el ( = May the god El protect) was supplanted by the nickname ‘Akev ( = “heel”), referring to the reputation he acquired as a “heel-holder.”[5] Jacob’s grabbing of his brother’s heel “becomes a kind of emblem of their future relationship.”[6] It also was a portent of several later episodes where he tried to secure through his own uninspired trickery “blessings that God [was] already willing to grant but that [were] made conditional on [his] asking for them.”[7]

In answer to Rebekah’s prayer about the meaning of the struggle among her two sons that had already begun before birth, she received the answer that “the elder [i.e., Esau] shall serve the younger [i.e., Jacob].”[8] According to BYU professor Catherine Thomas, “This divine announcement prophesied that Jacob, even though second born, should have the birthright and the attached patriarchal blessing. The Lord’s description of these two nations reflects choices made by these people in the premortal world as well as the choices they would yet make in mortality.”[9] By prefacing the story of Jacob with this prophecy, the scripture reader is informed that Jacob’s blessings eventually would be realized through divine intervention, not through “the improper means [Jacob] later employed to obtain his rights.”[10]

In this article, we will take a glimpse at three incidents that illustrate Jacob’s efforts to secure his blessings through “improper means”: 1. his attempt to buy of the birthright from Esau for a “mess of pottage”; [11] 2. his conspiring with Rebekah to trick Isaac into giving him Esau’s blessing; 3. his effort to possess as many as possible of the flocks of his wily father-in-law Laban (though in this latter instance, it was eventually revealed that he was helped by the Lord). In each case — by way of contrast to Abraham[12] and Eliezer[13] — Jacob does not ask in faith[14] and wait patiently for the Lord to bring about promised blessings “in his own time, and in his own way, and according to his own will,”[15] but tries to force God’s hand through his own anxious manipulations. However, by the time he is ready for his ultimate “wrestle with God,”[16] his soul is “full of charity towards all men,” and his “confidence [has become] strong in the presence of God.”[17] Jacob has become fit for the “doctrine of the priesthood to distill upon [his] soul,” “without compulsory means,” but rather gently and unforcedly “as the dews from heaven.”[18]

Figure 3. Jan Victors (1619-1676): Esau and the Mess of Pottage, 1653

Attempting to buy the birthright. Though there may be more to the story than what we have in scripture,[19] Genesis opens the account by telling us simply that “Jacob sod pottage: and Esau came from the field, and he was faint.”[20]

However, the few words that Esau utters give us what we need to see into Esau’s heart:

It is well known that in biblical dialogue all the characters speak proper literary Hebrew, with no intimations of slang, dialect, or ideolect. The single striking exception is impatient Esau’s first speech to Jacob in Genesis 25: “Let me gulp down some of this red red stuff.” Inarticulate with hunger, he cannot come up with the ordinary Hebrew term for “stew,” and so he makes do with ha’adom ha’adom hazeh—literally “this red red.”[21] But what is more interesting for our purpose is the verb Esau uses for “feeding,” hal’iteini. This is the sole occurrence of this verb in the biblical corpus, but in the Talmud it is a commonly used term with the specific meaning of stuffing food into the mouth of an animal.[22] … [I]n this instance, the writer … exceptionally allowed himself to introduce the vernacular term for animal feeding in order to suggest Esau’s coarsely appetitive character.[23]

The rapid-fire description in verse 34 of Esau’s subsequent behavior (“he did eat and drink, and rose up, and went his way”) “nicely expresses the precipitous manner in which Esau gulps down his food and, as the verse concludes, casts away his birthright.”[24]

However, BYU professor Arthur Henry King (1910-2000) noted that even though “Esau was obviously wrong,” it does not mean that Jacob is right.[25] Jacob’s mother had no doubt already told him about God’s promise that he would receive the birthright, and his attempt to buy it from Esau was not merely unnecessary but also an offensive vote of no confidence in the Lord. Besides, although “the gift of God” may be sold, it cannot “be purchased,”[26] as Nahum Sarna observed:[27]

[I]t is highly significant that the text only mentions Esau’s sale of the birthright but does not state that Jacob bought it. This is contrary to the usual biblical legal style. … The omission in the present story is another way of dissociating Jacob’s eventual ascendancy from the means he adopted.

Figure 4. Jacques Joseph Tissot (1836-1902):

Jacob Deceives Isaac

Trying to trick Isaac into giving him Esau’s blessing. Esau’s unworthiness is reinforced by the mention of his marriage to two Hittite women, “which were a grief of mind unto Isaac and to Rebekah.”[28] The issue of succession in the family is brought to the fore by the observation that “Isaac was old”[29] — for that reason he was apparently anxious to give a father’s blessing to “his eldest son,”[30] Esau. Note that under normal circumstances, Esau would have been called the “firstborn,” but scripture studiously avoids using this term since ultimately Jacob, not Esau, will receive the birthright.[31]

Of course, Isaac’s blessing does not convey the birthright itself. “Apparently, [the blessing and the birthright] were separate institutions. Nothing is said about the disposition of property”[32] as would have been the case had it been a birthright blessing.

The most important detail in the preface to the story is that “Isaac’s eyes were dim, so that he could not see.”[33] Isaac’s loss of vision allowed Rebekah and Jacob to carry out their deception. More importantly, scripture seems to imply that Isaac is also blind in a figurative sense: his “perception of reality about Esau’s worthiness to receive the blessing appears to have been clouded.”[34]

The details of Rebekah and Jacob’s conspiracy are not important to the theme of this article.[35] What should be realized, however, is that for a second time, Jacob’s deception is designed to secure Esau’s blessing through his own efforts rather than through patience in God’s promises to him, conditioned on his faithfulness. To his mother, Jacob admits that his actions may reveal him to his father as a “deceiver,”[36] but he “seems to be more concerned with the consequences of detection than with the morality of the act.”[37] Neither one seems to anticipate the high price of physical and emotional estrangement that will result.

Despite his age and blindness, Isaac seems to suspect that something is not right. “Deprived of his eyesight, Isaac summons to his aid the remaining senses of hearing, touch, taste and smell.”[38] Immediately after hearing the first word out of Jacob’s mouth — “My father”[39] — Isaac questions his identity. Heightening the dramatic tension, Isaac then wonders how the venison was obtained “so quickly.”[40] Jacob brazenly “invokes God’s name in an outright lie,”[41] saying that “the Lord God brought [the venison] to [him].”[42] Through the touch and smell of Jacob’s clothing and the taste of the meat, Isaac seems convinced at last and bestows the blessing.[43]

When Esau returned from his hunt, Isaac realized what had happened. Despite Esau’s complaint to his father that Jacob had now “supplanted [him] … two times,”[44] Isaac knew that “the blessing he [had] uttered [under the inspiration of heaven was] beyond recall.”[45] Thus, to Esau, he solemnly reaffirmed the promises of Jacob’s blessing: “yea, and he shall be blessed.”[46]

Though the blessing stood, it is important to note that “Rebekah and Jacob’s trouble is for nothing — the deception is not rewarded.”[47] The blessing Jacob received was not the birthright blessing — “it contains no promises of progeny or land.”[48] Later, however, when Rebekah “is forthright about her concerns” — reminding Isaac of her disgust at Esau’s marriages to the Hittite women and expressing her concern about Jacob’s marriage prospects — “the birthright blessing is finally given.”[49]

Nahum Sarna summarizes the point of this episode:[50]

[In the second blessing], Isaac confirms Jacob’s title to the birthright independently of the deception. Jacob is recognized to be the true heir to the Abrahamic covenant, which is why he must not marry outside of the family.

Figure 5. Jacob Meets Laban

The deceiver is deceived, but Jacob finally gets Laban’s goat(s). Jacob had been humbled in his hasty flight to Haran to escape the anger of Esau. This prepared to receive a divine encounter in vision[51] and subsequently to make a covenant with the Lord. Thus God actively began a tutorial designed to prepare Jacob for his unique and essential mission in life.

Having arrived in the village of his relatives, Jacob met his match in the wily Laban, his mother’s brother and the father of his future brides. Jacob, the heel-holder, will be the subject of multiple deceptions at Laban’s hand.

Jacob’s sudden appearance as a solitary and an empty-handed refugee must have raised some questions in the mind of the astute Laban. No doubt he recalled “that the last time someone came from the emigrant branch of the family in Canaan, he brought ten heavily laden camels with him.”[52] Although his warm embrace was probably nothing more than standard hospitality, the Jewish scholar Rashi cynically surmised that Laban’s intent was “to see if Jacob had gold secreted on his person.”[53]

Lacking the means to pay a bride-price, Jacob quickly proposed a generous offer to work seven years for Rachel’s hand in marriage.[54] “Laban’s reply is a piece of consummate ambiguity naively taken by Jacob to be a binding commitment.”[55]

After a night where the marriage was consummated, we are told in the terse economy of style characteristic of Genesis that “in the morning, behold, it was Leah.”[56] Laban’s reply when he was confronted by Jacob is similarly to the point: “It must not be so done in our country, to give the younger before the firstborn.”[57] Robert Alter comments:[58]

Laban is an instrument of dramatic irony: his perfectly natural reference to “our [country]” has the effect of touching a nerve of guilty consciousness in Jacob, who in his [country] acted to put the younger before the firstborn. This effect is reinforced by Laban’s referring to Leah not as the elder but as the firstborn (bekhirah). It has been clearly recognized since late antiquity that the whole story of the switched brides is a meting out of poetic justice to Jacob — the deceiver deceived, deprived by darkness of the sense of sight as his father is by blindness, relying, like his father, on the misleading sense of touch. The Midrash Bereishit Rabba vividly represents the correspondence between the two episodes: “And all that night he cried out to her, ‘Rachel!’ and she answered him. In the morning, ‘and,… look, she was Leah.’ He said to her, ‘Why did you deceive me, daughter of a deceiver? Didn’t I call out Rachel in the night, and you answered me!’ She said: ‘There is never a bad barber who doesn’t have disciples. Isn’t this how your father cried out Esau, and you answered him?’”

However, as Nahum Sarna points out, “retributive justice is not the only motif. Just as Jacob’s succession ot the birthright was divinely ordained, irrespective of human machinations,[59] so Jacob’s unintended marriage to Leah is seen as the working of Providence, for from this unplanned union issued Levi and Judah, whose offspring … [sustained] the two great institutions of the biblical period, the priesthood and the Davidic monarchy.”[60]

Figure 6. Jusepe de Ribera (1591-1652): Jacob With Laban’s Flocks

After having served a second seven years for Rachel, Jacob has obtained a large family, but still lacks the personal means to provide for them independently of Laban.[61] At last, he sees an opportunity to enrich himself through making what seems to be a bargain for his father-in-law. In return for Jacob’s continued service Jacob would ask only for the relatively rare “speckled and spotted cattle, and all the brown cattle among the sheep, and the spotted and speckled among the goats.”[62] We will pass over the details of this episode to focus on its lesson: namely, that once more Jacob’s blessings were, as voiced by Shakespeare’s Antonio, “not in his power to bring to pass, But sway’d and fashion’d by the hand of heaven.”[63]

Two different accounts of Jacob’s actions, meant to assure the multiplication of his sheep and goats, are given in Genesis: one focuses on his implausible strategy of placing specially-prepared sticks in front of mating flocks;[64] the other, relying on divinely suggested and directed propagation of the stronger animals.[65] Sarna points out that these strategies need not be seen as contradictory if one assumes the first was simply an “elaborate display put on by Jacob in order to mask his secret technique.”[66]

Explicitly acknowledging for the first time in scripture that it was God, not him, who deserved credit for the idea that “gave the increase,”[67] Jacob described his revelatory dream to Leah and Rachel.[68] Further, he told them that God had commanded him to “get … out from this land, and return unto the land of [his] kindred.”[69] To this they both agreed heartily.[70]

Having learned through experience, Jacob was ready now to “confess … [God’s] hand in all things, and [to] obey … his commandments.”[71] Thus was fit for the ultimate stage of his divine tutorial.

Figures 7a and b. Jacob Wrestles the Angel; Jacob Embraces Esau[72]

Jacob’s wrestle with God and Esau. Robert Alter points out that “the image of wrestling has been implicit throughout the Jacob story.”[73] Matthew L. Bowen explains how, in this culminating moment of Jacob’s journey, the transformation of his character is revealed through Hebrew wordplay:[74]

In the biblical account, the word “embraced” constitutes a paronomasia on the name Jacob[75] similar to the paronomasia on “wrestle” (yēʾābēq) and “Jacob” (yaʾăqōb). This wordplay is a sublime pun on “Jacob” that emphasizes his transformation from his former identity: he is no longer the “heel [-grabber]” or “usurper,” but “the embraced,” i.e., “the at-one-ed.” This pun confirms Hugh Nibley’s suggestion that “the word conventionally translated as ‘wrestled (yēʾāvēq)’ can just as well mean “embraced.”[76]

Going further, Andrew Skinner points out how the sequence of events where Jacob received additional temple blessings from God is apparent:[77]

- Jacob wrestled all night for a blessing in the face of great trial, in which he, his family, and the fulfillment of the covenant all faced annihilation.

- Jacob was asked for his name, and he disclosed his own given name to a divine messenger or minister.

- Jacob was then presented with a new name.

- Jacob was next given an endowment of power, which would be recognized in the eyes of both God and men.

- Jacob was finally given an additional blessing, and the divine minister was not heard from again.

The text is silent about the nature of the additional blessing. We get only Jacob’s response to the blessing bestowed upon him at that moment. But what an arresting response it was, for it tells us what we may read into the narrative. The text says, “And he [the divine being] blessed him there. … And Jacob called the name of the place Peniel: for I have seen God face to face, and my life is preserved.”[78] Let there be no misunderstanding; the text says Jacob was blessed, and then the very next words out of his mouth which are (or, perhaps, can be) reported to us are, “I have seen God face to face, and my life is preserved.”[79] Thus, the event occurring between verses 29 and 30, though only implied, was no less than the ultimate theophany of Jacob’s life — his being ushered into the presence of God to have every promise of past years sealed and confirmed upon him.

During the struggle with the divine messenger, Jacob was badly injured. According to Alter: “Jacob, whose name can be construed as ‘he who acts crookedly,’ is bent, permanently lamed, by his nameless adversary in order to be made straight before his reunion with Esau.”[80]

Earlier, the “greatly afraid and distressed”[81] Jacob had offered the most humble and impassioned prayer in his life in anticipation of his encounter with a potentially hostile Esau.[82] The “big surprise in the story of the twins” is that “instead of lethal [wrestling], Esau embraces Jacob in fraternal affection.”[83] His weakness having been turned to strength,[84] Jacob’s new name was Israel, “a prince [possessing] power with God and with men, and [having] prevailed.”[85] He was now fully prepared to shoulder the blessings and responsibilities of the house of Abraham.

The Why

Shakespeare’s Hamlet once boasted that he would destroy his enemies by “blow[ing] them [to] the moon.”[86] Later, when his “deep plots”[87] failed and his rashness faded, he was left helpless and in despair. It was then that Divine Providence exercised its incontrovertible prerogative, bringing him effortlessly “what he had so long and eagerly desired.”[88] Afterward, he humbly confessed to the agreeing nod of his friend Horatio:[89]

There’s a divinity that shapes our ends,

Rough-hew them how we will —

We learn from the story of Jacob that rough-hewing of one’s own ends, trying to leave God out of the picture, is a tedious, sometimes painful, and always futile pastime.

“Man proposes, but God disposes.”[90] No human folly is more common or more destructive than the attempt to wrest our future from the hand of God so we may place it, as we suppose, securely into our own hands. After the inevitable disaster that follows an awakening from the illusion of exclusive self-reliance, those wise enough to listen will hear the kind, corrective voice of the Father, “I am the gardener here, and I know what I want you to be.”[91]

Thanks to Kathleen M. Bradshaw and Stephen T. Whitlock for their careful proofreading and valuable suggestions.

Further Study

See the Reference section below for complete access information for the following:

For discussions of the meaning and significance of Jacob’s vision of the ladder, see J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1; J. M. Bradshaw, Faith, Hope, and Charity, p. 34; and J. M. Bradshaw, et al., God’s Image 2, p. 395.

For discussions of Jacob’s wrestling with an angel of the Lord in a temple context, see J. J. Huston, Integration of Temples; A. C. Skinner, Jacob.

For an insightful reading on the many allusions the Book of Mormon character Enos makes to the story of Jacob, see see M. L. Bowen, Jacob, Enos.

For a scripture roundtable video from The Interpreter Foundation on the subject of Gospel Doctrine lesson 10, see https://interpreterfoundation.org/scripture-roundtable-60-old-testament-gospel-doctrine-lesson-10-birthright-blessings-marriage-in-the-covenant/.

References

Alter, Robert, ed. Genesis. New York City, NY: W. W. Norton, 1996.

Bowen, Matthew L. "Jacob, Enos, Israel, and Peniel." In Name as Key-Word: Collected Essays on Onomastic Wordplay and the Temple in Mormon Scripture, edited by Matthew L. Bowen, 83-90. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2018.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. "The ark and the tent: Temple symbolism in the story of Noah." In Temple Insights: Proceedings of the Interpreter Matthew B. Brown Memorial Conference ‘The Temple on Mount Zion,’ 22 September 2012, edited by William J. Hamblin and David Rolph Seely. Temple on Mount Zion Series 2, 25-66. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation/Eborn Books, 2014.

———. Creation, Fall, and the Story of Adam and Eve. 2014 Updated ed. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. "Faith, hope, and charity: The ‘three principal rounds’ of the ladder of heavenly ascent." In “To Seek the Law of the Lord”: Essays in Honor of John W. Welch, edited by Paul Y. Hoskisson and Daniel C. Peterson, 59-112. Orem, UT: The Interpreter Foundation, 2017.

Brown, Hugh B. 1968. God Is the Gardener (31 May 1968). In BYU Speeches. https://speeches.byu.edu/talks/hugh-b-brown_god-gardener/. (accessed February 28, 2018).

Brown, S. Kent. Class Notes, Old Testament Class, Brigham Young University, 1979.

Ginzberg, Louis, ed. The Legends of the Jews. 7 vols. Translated by Henrietta Szold and Paul Radin. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1909-1938. Reprint, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Huston, Jamie J. "The integration of temples and families: A Latter-day Saint structure for the Jacob cycle." Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 13 (2015): 131-67. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/the-integration-of-temples-and-families-a-latter-day-saint-structure-for-the-jacob-cycle/. (accessed March 3, 2018).

Josephus, Flavius. "The Antiquities of the Jews." In The New Complete Works of Josephus. Translated by Paul L. Maier and William Whiston, 47-664. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications, 1999.

Kempis, Thomas à. 1441. The Imitation of Christ: A New Reading of the 1441 Latin Autograph Manuscript. Translated by William C. Creasy. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2007.

King, Arthur Henry. Class Notes, Reading the Scriptures Class, Brigham Young University, 1980.

LDS Bible Dictionary. In LDS Scriptures. https://churchofjesuschrist.org/scriptures/bd/prayer?lang=eng. (accessed February 28, 2018).

Mabillard, Amanda. Divine Providence in Hamlet. In Shakespeare Online. http://www.shakespeare-online.com/plays/hamlet/divineprovidence.html. (accessed February 28, 2018).

Mess of Pottage. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mess_of_pottage. (accessed March 2, 2018).

Nibley, Hugh W. 1975. "Sacred vestments." In Temple and Cosmos: Beyond This Ignorant Present, edited by Don E. Norton. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 12, 91-138. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992.

———. 1975. The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment. 2nd ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005.

Ricks, Stephen D. "The garment of Adam in Jewish, Muslim, and Christian tradition." In Temples of the Ancient World, edited by Donald W. Parry, 705-39. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1994.

Sarna, Nahum M., ed. Genesis. The JPS Torah Commentary, ed. Nahum M. Sarna. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society, 1989.

Shakespeare, William. 1594. "The Merchant of Venice." In The Riverside Shakespeare, edited by G. Blakemore Evans, 250-85. Boston, MA: Houghton-Mifflin Company, 1974.

———. 1600. "The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark." In The Riverside Shakespeare, edited by G. Blakemore Evans, 1135-97. Boston, MA: Houghton-Mifflin Company, 1974.

Skinner, Andrew C. 1994. "Jacob in the presence of God." In Sperry Symposium Classics: The Old Testament, edited by Paul Y. Hoskisson, 117-32. Provo and Salt Lake City, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2005. https://rsc.byu.edu/archived/sperry-symposium-classics-old-testament/jacob-presence-god. (accessed March 3, 2018).

Thomas, Catherine. "Jacob rightly received blessings." Salt Lake City, UT: Church News, June 25, 1994.

Tvedtnes, John A. "Priestly clothing in Bible times." In Temples of the Ancient World, edited by Donald W. Parry, 649-704. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1994.

Endnotes

The phrase alludes to Esau’s sale of his birthright for a meal (“mess”) of lentil stew (“pottage”) in Genesis 25:29-34 and connotes shortsightedness and misplaced priorities. …

Its first attested use, already associated with Esau’s bargain, is in the English summary of one of John Capgrave’s sermons, c1452, “[Jacob] supplanted his broþir, bying his fader blessing for a mese of potage.” In the sixteenth century it continues its association with Esau, appearing in Bonde’s Pylgrimage of Perfection (1526) and in the English versions of two influential works by Erasmus, the Enchiridion (1533) and the Paraphrase upon the New Testament (1548): “th’enherytaunce of the elder brother solde for a messe of potage.” It can be found here and there throughout the sixteenth century, e.g. in Johan Carion’s Thre bokes of cronicles (1550) and at least three times in Roger Edgeworth’s collected sermons (1557). Within the tradition of English Biblical translations, it appears first in the summary at the beginning of chapter 25 of the Book of Genesis in the so-called Matthew Bible of 1537 (in this section otherwise a reprint of the Pentateuch translation of William Tyndale), “Esau selleth his byrthright for a messe of potage”; thence in the 1539 Great Bible and in the Geneva Bible published by English Protestants in Geneva in 1560.[9] According to the OED, Coverdale (1535) “does not use the phrase, either in the text or the chapter heading…, but he has it in 1 Chronicles 16:3 and Proverbs 15:7.” Miles Smith used the same phrase in “The Translators to the Reader,” the lengthy preface to the 1611 King James Bible, but by the seventeenth century the phrase had become very widespread indeed and had clearly achieved the status of a fixed phrase with allusive, quasi-proverbial, force.

Blood was considered to constitute the life-essence and was widely believed to contain magical properties. It was a symbol of strength and vitality. A suggestion that Esau thought the “red stuff” to be a blood broth is most plausible. His primitive instincts were aroused by the sight. He expected his vitality to be renewed by drinking it.

Jesus seems to allude directly to this event in his Parable of the Prodigal Son: “And he arose, and came to his father. But when he was yet a great way off, his father saw him, and had compassion, and ran, and fell on his neck, and kissed him” (Luke 15:20). The Lord, speaking to Enoch, describes a similar “at-one-ment” between Enoch’s Zion and the Latter-day Zion: “Then shalt thou and all thy city meet them there, and we will receive them into our bosom, and they shall see us; and we will fall upon their necks, and they shall fall upon our necks, and we will kiss each other” (Moses 7:63).