This series is cross-posted with the permission of Book of Mormon Central

from their website at Pearl of Great Price Central

Figure 1. Thomas Cole, 1801-1848: Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, 1828.

East of Eden

In his characteristic epic style, Thomas Cole depicted Adam and Eve being driven from the lush garden to live in the relative wilderness of the mortal world. The exit of the Garden of Eden—and presumably the only means of access—is on the east side, at the end farthest away from the mountain of God’s presence. The image of the tiny couple is almost lost in the wide expanse of the landscape, emphasizing the greatness of the power of God and the grandeur of His Creation as compared with the forced humility of fallen mankind. The light emanating from the Garden contrasts with the darkness of the way ahead for Adam and Eve.

Adam and Eve’s expulsion is described twice in Moses’ account, with different terms used in each case.[1] The Hebrew word shillah (“send him forth”) in verse 23 is followed by the harsher term geresh (“drove out”), used in Genesis 3:24. Significantly, the same two terms are used in the same order by the Lord to describe how Pharaoh would drive Israel away from their familiar comforts in Egypt[2]—their erstwhile “Eden”—suggesting that we are not meant to read Adam and Eve’s exit from Eden as depicting a unique event but rather, in the case of their expulsion from Eden, as demonstrating a repeated type of mankind’s difficulty, in its fallen state, to “stand in holy places” and not be “moved.”[3]

Though the scriptural admonition to “stand in holy places and be not moved”[4] is a familiar one, the relevance of its symbolism to the story of Adam and Eve has been underappreciated. In this essay, we will explore how one’s fitness to stand in holy places was understood in ancient sources, showing the paramount importance of this idea in the Old and New Testament—and its particular relevance for our own time. Indeed, Avivah Zornberg has argued that to “hold [one’s] ground” in sacred circumstances is the meaning of being itself—“kiyyum: to rise up (la-koom), to be tall (koma zokufa) in the presence of God.”[5]

Figure 2. Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378-1455): Creation of Adam, from Gates of Paradise, 1425-1452.

Adam and Eve’s Standing in Eden

According to Jewish tradition, the dust used to create Adam was taken from two places: 1. From the four corners of the earth (so that wherever he died, he would be accepted for burial), and 2. From the “sacred center,” the place of Adam’s altar and the location of the temple:

“God took his dust from the place of which it is said, ‘You shall make an altar of earth for Me—I wish that he may gain atonement, and that he may be able to stand.’”[6]

In contrast to cattle, which “do not stand to be judged”[7] (i.e., are not held accountable for their actions[8]), a midrashic account of Adam’s creation specifically highlights his first experience after being filled with the breath of life:[9] namely, the moment when God “stood him on his legs.”[10] According to Zornberg,[11] it is in the ability to stand in the presence of God that one specifically demonstrates the attainment of full “majesty and strength,” a divine quality Adam will lose through his subsequent transgression:

Before the sin, Adam could “hear God speaking and stand on his legs, … he could withstand it.”[12] After the sin, he hides; the midrash imagines Adam and Eve as shrinking[13] essentially pretending not to be. In another midrash, God says, “Woe Adam! Could you not stand in your commandment for even one hour? Look at your children who can wait three years for the fruit tree to pass its forbidden stage [orlah]”[14]

Zornberg is puzzled by the allusion to an immature fruit tree, calling it “a strange analogy,” and noting that “the capacity to wait seems to be the issue here.”[15] However, this idea, though uncommon, is not completely without parallel. For example, the fifteenth-century Adamgirk does not see Adam and Eve’s attempt to “become divine,”[16] as forever futile, but merely premature—not being, as yet, “in its time.”[17] As Joseph Smith is thought to have written: “That which is wrong under one circumstance, may be, and often is, right under another.”[18]

Figure 3. The Harrowing of Hell. The Barberini Exultet Roll, ca. 1087.

Medieval artistic convention makes it clear that Christ was imagined as raising the dead to eternal life by the same gesture that was used to create Adam and stand him on his feet.[19] Likewise, we note the Old Testament literary formula that nearly always follows descriptions of miraculous revivals of the dead with the observation that they “stood up upon their feet.”[20] More generally, in Christian iconography this gesture is used in scenes representing a transition from one state or place to another. For example, a depiction at the Church of San Marco in Venice shows God taking Adam by the wrist to bring him through the door of Paradise and to introduce him into the Garden of Eden.[21] Another Christian scene shows God taking Adam by the wrist as he and Eve receive the commandment not to partake of the Tree of Knowledge.[22] Likewise, scripture and pseudepigrapha describe how prophets such as Enoch,[23] Abraham,[24] Daniel,[25] and John[26] are grasped by the hand of an angel and raised to a standing position in key moments of their heavenly visions.[27]

It is by being raised by the hand to the upright position that we are made ready to hear the word of the Lord. It is no mere coincidence that before heavenly messengers can perform their errands to Ezekiel,[28] Daniel,[29] Paul,[30] Alma the Younger,[31] and Nephi[32] they must first command these seers to stand on their feet.[33] As biblical scholar Robert Hayward has said: “You stand in the temple,[34] you stand before the Lord,[35] you pray standing up[36]—you can’t approach God on all fours like an animal. If you can stand, you can serve God in His temple.”[37] If you are stained with sin, you cannot stand in His presence.[38]

Figure 4: Stephen T. Whitlock, 1951-: Tree Near British Camp, 2009.

Although to be banished from the Garden of Eden “is to lose a particular standing ground,”[39] it was always God’s intention to restore Adam and Eve to their former glory,[40] enabling their “confidence” to again “wax strong”[41] in His presence. Succinctly expressing the hopelessness of Adam’s predicament in the absence of God’s remedy, midrash states: “If it were not for Your mercy, Adam would have had no standing (amidah).”[42]

Israel’s Failure to Stand at Sinai

We have already mentioned the parallel between the first couple’s expulsion from Eden and Israel’s exodus from Egypt to the places of their probation. As the path of exaltation was revealed through five covenants given to Adam and Eve after the Fall,[43] so Israel’s salvation was also understood to have been made contingent on its acceptance of the five parts of God’s law.[44] Indeed, Rashi wrote of how all creation from the beginning waited in expectation for this Law to be revealed:

All the works of the beginning are suspended (literally, hanging and standing) until the sixth day of Sivan, which is destined for the giving of the Torah.[45]

Implicit in such commentary is the idea that the very earth and heavens are preserved by means of the same covenant that humankind makes in order to assure its own standing with God. The original covenant from which all others derive was made before the “foundation of the world,”[46] when the members of the Godhead agreed to create the universe.[47] Afterward, the terms of this covenant were said to have been marked or “engraved” upon Creation itself, symbolically delimiting the bounds beyond which they were not to pass. For example, in the book of Proverbs, Wisdom speaks poetically as having been present “when [God] prepared the heavens, … when he engraved a circle upon the face of the deep:… when he set for the sea its engraved mark… when he engraved the foundations of the earth.”[48] In modern times, Joseph Smith also anticipated with great longing the day when he, like the author of Proverbs, would be able to “gaze upon eternal wisdom engraven upon the heavens.”[49] Themes relating to these primordial “bounds” also appear in the Doctrine and Covenants[50] and in other statements by Joseph Smith.[51]

Figure 5. William Blake, 1757-1827: God Creating the Universe, 1824.

Illustrating the idea of the engraving of divine law on the fabric of the cosmos is the well-known print by William Blake, entitled “God Creating the Universe.” The solitary posture of the form seems to have been prescribed by Milton, who wrote of the moment when the Almighty “took the golden Compasses prepar’d… to circumscribe This Universe, and all created things: One foot he centred, and the other turn’d Round through the vast profunditie obscure.”[52]

A corollary to the idea of God having ordered Creation through the establishment of Law is the Jewish teaching that man’s continued defiance of the great covenant could cause the entire universe to “dissolve and disappear,” bringing back the primordial state of a watery earth. It was, in fact, this very state that had been brought on by the rebellion of mankind in the prelude to Noah’s flood, that was later witnessed in the total annihilation of Sodom, and that was also described by the prophets as they envisioned the complete desolation of a world destroyed by wickedness.[53] Thus, midrash asserted: “God made a condition with the works of the Beginning—If Israel accepts the Torah, you will continue to exist; if not, I will bring you back to chaos.”[54]

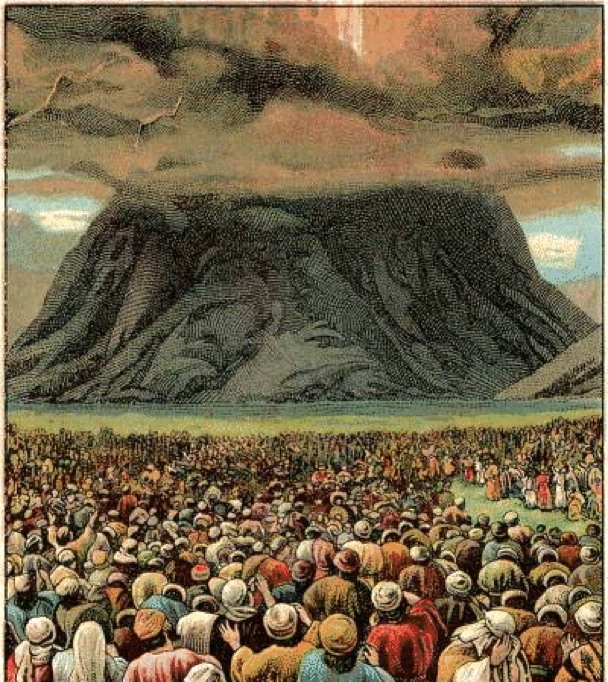

Figure 6: The Children of Israel at Mount Sinai

Israel, however, proved themselves unready to accept the fulness of God’s law at Sinai.[55] They preferred that Moses ascend the holy mountain alone.[56] Painting a vivid word picture of the Israelites’ inability to stand unmoved in the divine presence, Rashi explains that when they heard the sound of the voice of God “they moved backwards and stood at a distance: they were repelled to the rear a distance of twelve miles—that is the whole length of the camp. Then the angels came and helped them forward again.” Zornberg reasons: “If this happened at each of the Ten Commandments, the people are imagined as traveling 240 miles in order to stand in place!”[57] Though this imagery is, of course, figurative, it is highly instructive.

We see this same movement away from God and toward the regions of death at the incident of the Golden Calf.[58] Before their sin, the Israelites looked upon the divine flames at the top of the mountain without fear, but as soon as they had sinned, they could not even bear to see the face of Moses, God’s intermediary.[59] On the other hand, Moses, like Jesus at the Transfiguration,[60] had been covered by a glorious cloud[61] and was made like God Himself.[62] Moses then stood to Israel as God stood to him and, having received the power of an eternal life, he became known in the Samaritan literature as “the Standing One.”[63]

Comparing the sin of the Israelites to the transgression of Adam, midrash has God reproaching them as follows:[64]

Like Adam, the people were destined to live forever, but “when they said, ‘These are your gods, O Israel!,’ death came upon them. God said, ‘You have followed the system of Adam, who did not stand the pressure of his testing for three hours.…” ‘I said, “You are gods.…” But you went in the ways of Adam,’ so ‘indeed like Adam you shall die. And like one of the princes you shall fall’—you have brought yourself low.”[65]

The midrash uses the imagery of the Fall, with a perfect consistency. The sin, as such, is not mentioned. Instead, what Adam, and again the Israelites, represents is a kind of spinelessness, a vapidity … The word that is used in Sanhedrin 38b to describe the sin is sarah, which implies exactly this aesthetic offensiveness: it holds nuances of evaporation, loss of substance, and the offensive odor of mortification. “O my offense is rank, it smells to heaven.”[66] It signifies a failure to stand in the presence of God, to maintain the posture of eternal life. “You have brought yourselves low”: man, the midrash boldly implies, does not really want full and eternal being. He chooses death, lessened being. What looks like defiance is an abandonment of a difficult posture.

The Fall of the Temple Guards at Jesus’ Arrest

In his moving discourse on the Atonement, Elder Bruce R. McConkie compared the Garden of Eden to the Garden of Gethsemane.[67] Note that a “serpent” was present on both occasions. In the first instance, one who had been “drawn away”[68] by Satan incited Eve to transgress God’s command, resulting in expulsion from Eden. In the second, Jesus bore our transgressions, resulting in an arrest and departure incited by the “son of perdition.”[69] In the Garden of Gethsemane, however, there was no deception, for Jesus already knew “all things that should come upon him.”[70] Nor could the Christ be compelled by the officers sent to arrest Him. Though the incident occurred “in a situation of apparently complete inequality of power, … it is not they but He who takes charge.”[71] As Elder James E. Talmage wrote: “The simple dignity and gentle yet compelling force of Christ’s presence proved more potent than strong arms and weapons of violence.”[72]

Figure 7. James Tissot, 1836-1902: The Guards Falling Backwards, 1886-1894

While Matthew, Mark, and Luke’s accounts highlight the perfidy of Judas as the one who identified his Master to the temple guards, the gospel of John instead emphasizes Christ’s own mastery of the situation. Perhaps this is why kiss of Judas does not appear in John’s narrative. Explains Ridderbos “Judas’ task of identifying Jesus had been taken out of his hands.”[73] Instead, when Judas enters the scene, Jesus is shown in full control of the arresting party by His startling self-identification:[74]

4 Jesus therefore, knowing all things that should come upon him, went forth, and said unto them, Whom seek ye?

5 They answered him, Jesus of Nazareth. Jesus saith unto them, I am he. …

6 As soon then as he had said unto them, I am he, they went backward, and fell to the ground.

The King James translation of the Greek phrase ego eimi as “I am he” obscures an essential detail. In reality, Jesus has not said, “I am he,” but rather “i am,” using a divine name that directly identifies Him as being Jehovah.[75] Thus, asserts Raymond E. Brown, it is clear that the fall of the temple guards is no mere slapstick scene that might be “explained away or trivialized. To know or use the divine name, as Jesus does [in replying with ‘i am’], is an exercise of awesome power.”[76]

This event is nothing less than a replay of the scene of the children of Israel at Sinai discussed earlier.[77] In effect, in the gospel of John, the narrative takes the form of an eyewitness report[78] of a solemn revelation to the band of arresting Jewish temple guards[79] that they were standing, as it were, in a “Holy of Holies” made sacred by the presence of the embodied Jehovah, and that they, with full comprehension of the irony of their pernicious intent, were about to do harm to the very Master of the Lord’s House, whose precincts they had been sworn to protect. As with the Israelites at Sinai who were unworthy and thus unable to stand in the holy place, “those of the dark world fell back, repelled by the presence of the Light of the world.”[80]

To delve further into the symbolism of the scene, remember that the Jews were generally prohibited from pronouncing the divine name, Jehovah. As an exception, that Name was solemnly pronounced by the High Priest standing in the most holy place of the temple once a year, on the Day of Atonement. Upon the hearing of that Name, according to the Mishnah, all the people were to fall on their faces. Was it any coincidence, then, that Jesus Christ, the great High Priest after the order of Melchizedek, boldly proclaimed His identity as the great “I AM” at the very place and on the very night He atoned for the sins of the world? Ironically, the temple guards who failed to fall on their faces at the sound of the divine Name as prescribed in Jewish law were instead thrown on their backs in awestruck impotence.

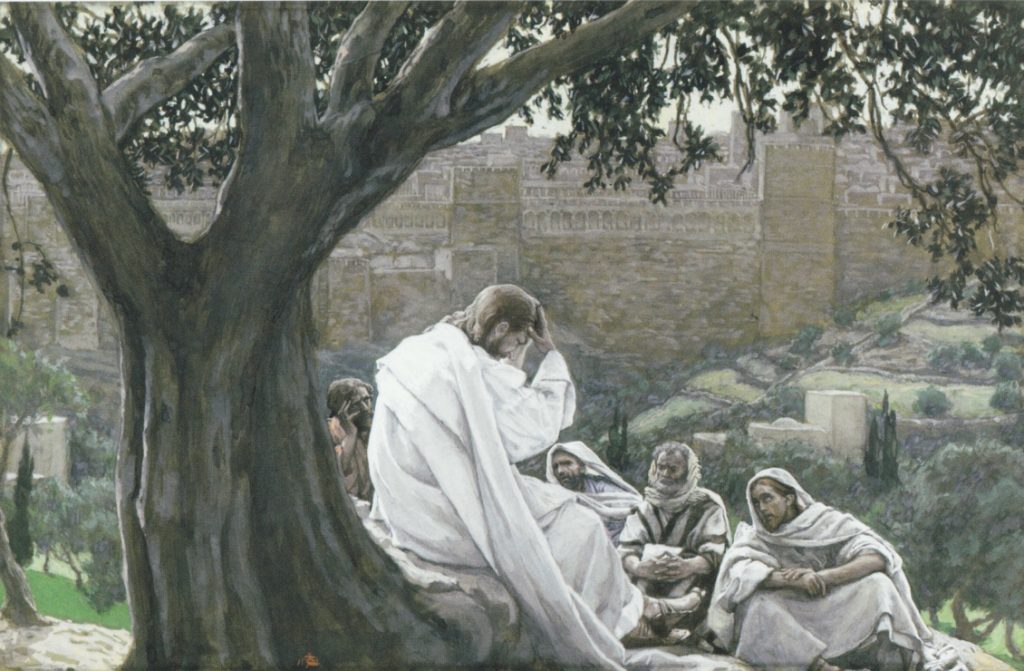

Figure 8. J. James Tissot, 1836-1902: The Prophecy of the Destruction of the Temple, 1886-1894.

Standing in Holy Places in the Latter Days

The only direct mention in the New Testament of the idea of “stand[ing] in the holy place” is in Matthew 24:15:

When ye therefore shall see the abomination of desolation, spoken of by Daniel the prophet, stand in the holy place, (whoso readeth, let him understand:)

Here the phrase is used descriptively, as part of Jesus’ discussion of the warning signs to which His disciples would be wise to attend. The plain meaning of the verse becomes more clear when it is rendered in conjunction with v. 16, with ellipsis, as follows: “When ye therefore shall see the abomination … stand in the holy place, … let them … flee into the mountains.”[81] Essentially, the disciples are being told that the sign by which they will know that they should “flee into the mountains” is the event of an “abomination” having been set up to “stand” in the “holy place” of the Jerusalem Temple—in other words, following Mark 13:14, “standing where it ought not to be.”

In view of the fact that the “abomination” referred to by Daniel involved a disruption of temple sacrifices, most scholars accept that the “abomination” prophesied by Jesus would occur in the lifetime of the disciples had something to do with the desecration of Herod’s temple. The problem is that, as Richard T. France admits, none of the possibilities adduced for a specific event of temple desecration in the first century CE “quite fits what [the verse in Matthew] says.”[82]

As a distinctly different possibility, Peter G. Bolt has argued that Jesus’ reference to the “abomination” that would precede the destruction of Jerusalem was more likely a prophecy of the violent and ultimately fatal profanation of the temple of His own body—which He previously had said could be destroyed and raised up in three days (Matthew 26:61; Mark 14:58; John 2:19). Bolt asserts that in quoting the prophet Daniel, the Savior was using “apocalyptic language preparing the disciples for [His own] coming death. This fits with the rest of [the] story, for [there could be no] greater act of sacrilege than the destruction of God’s Son in such a horrendous way.”[83] Had not Jesus referred to Himself earlier in Matthew 12:6 as “one greater than the temple” (Matthew 12:6)? Note also Craig S. Keener’s view that Daniel 9:26 “associates the [“abomination that maketh desolate”] with the cutting off of an anointed ruler, close to the time of Jesus.”[84]

While confirming that the event in question described above was somehow connected with “the destruction of Jerusalem,” the Joseph Smith Translation (JST) differs with the King James Version in its prescriptive rendering of the key phrase:

When you, therefore, shall see the abomination of desolation, spoken of by Daniel the prophet, concerning the destruction of Jerusalem, then you shall stand in the holy place; whoso readeth let him understand.[85]

Also of interest is a verse, inserted later in the chapter by the Prophet, which speaks of a second “abomination of desolation” that is destined to occur “in the last days”:

And again, in the last days, the abomination of desolation, spoken of by Daniel the prophet, will be fulfilled.[86]

Doctrine and Covenants 45:31-33 reiterates and further explains the events described in Matthew 24:

31 And there shall be men standing in that generation, that shall not pass until they shall see an overflowing scourge; for a desolating sickness shall cover the land.

32 But my disciples shall stand in holy places, and shall not be moved; but among the wicked, men shall lift up their voices and curse God and die.[87]

33 And there shall be earthquakes also in divers places, and many desolations; yet men will harden their hearts against me, and they will take up the sword, one against another, and they will kill one another.

The central message of these verses is that in spite of the “overflowing scourge” of a “desolating sickness” that “shall cover the land,” the “disciples shall stand in holy places and shall not be moved.” Note that in every reference to this concept in modern revelation[88] the idea that the Saints should “stand in holy places” is connected to descriptions of the latter-day gathering and the destruction that will precede the Savior’s Second Coming.[89]

Where are the “holy places” in which we are to stand? In answer to this question, Elder David A. Bednar has drawn parallels to the first Passover, when the obedient Israelites marked their homes with lamb’s blood, consumed the sacred meal, and shut the door on passing death. Note that the Israelites ate while standing.[90] Elder Bednar stated his belief that someday there will be a kind of latter-day Passover.[91] In light of such teachings, the frequently heard suggestion that such “holy places” include temples, stakes, chapels, and homes seems wholly appropriate.[92] However, it should be remembered that what makes these places holy—and secure—are the covenants kept by those standing within. Sodom itself could have been a place of safety had there been as few as ten righteous in the city to “pray on behalf of all of them.”[93]

Another vivid picture of such “holy places” is drawn for us in Isaiah[94] and the Doctrine and Covenants, where the kingdom of God is described as a tent whose expanse increases continually outward from the “center place”[95] with the establishment of “stakes, for the curtains or strength of Zion.”[96] It is “in Zion, and in her stakes, and in Jerusalem” that are to be found “those places which [God has] appointed for refuge.”[97] God’s whole work and glory is to draw the people of the world to such places of safety, the express purpose of the Church being “for the gathering of his saints to stand upon Mount Zion.”[98]

Those who are determined to stand and not be moved will pitch their “tent with the door thereof towards the temple,”[99] the place of God’s presence where He covenants with His people. On the other hand, to knowingly and deliberately place oneself outside the tent of Zion through failure to make or keep saving covenants100 is to court mortal danger. Only through “cheerfully do[ing] all things that lie in our power,”101 while relying on “the merits, and mercy, and grace of the Holy Messiah”102 to make up our lack, can we be filled with sufficient faith to “stand still, with the utmost assurance to see the salvation of God.”103]

Conclusions

In words once sung to those who aspired to enter the temple,[104 the Psalmist asks: “Who shall ascend into the hill of the Lord? or who shall stand in his holy place?”105 The consistent answer from scripture is: “He that hath clean hands, and a pure heart.”106] Even with the best intentions, of course, no mortal is capable of remaining fully in this state for very long. However, the permanence of this blessing eventually can be realized through lifelong persistence in a process of engagement and reengagement in sincere repentance and faithfulness to covenants—covenants that must be frequently renewed by participation in the ordinances of the Gospel. As Chauncey Riddle has written:[107]

[Human] beings may be saved only by binding themselves to Christ.[108 It is as if our task were to stand straight and tall before Father, but because of the Fall, we are broken and twisted. The Savior is our straight and tall splint. If we bind ourselves to Him, wrap strong covenants around us and Him that progressively draw us up into His form and nature, then we can become righteous as He is and can be saved.109]

In spite of the bruised knees and tired limbs that this repeated cycle of standing and falling requires, our hearts are full of gratitude to God daily for the privilege of living for a while on an imperfect earth, for this is the way we gain our knowledge. Zornberg insightfully summarizes this lesson from Jewish tradition:

The Talmud makes an extraordinary observation about the paradoxes of “standing”: “No man stands on [i.e., can rightly under-stand] the words of Torah, unless he has stumbled over them.”[110 To discover firm standing ground, it is necessary to explore, to stumble, even to fall.111]

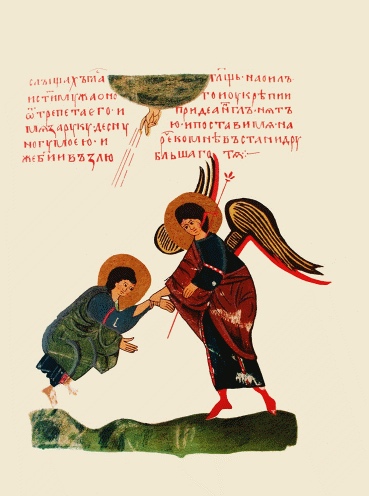

Figure 9. Yahoel Lifts the Fallen Abraham, Sylvester Codex, 14th century

In our repeated falls, we should be reassured in the knowledge that, like the Israelites at Sinai, we can receive help from “angels” appointed to assist our return.[112 Such a scene is depicted above, where the fallen Abraham gratefully testified that the Angel Yahoel “took me by my right hand and stood me on my feet.”113]

The continual challenges endemic in a disciple’s life should teach us something about “standing” itself: namely, that what might appear to the naïve as a “static position” will, with experience, eventually be better understood as “a point of equilibrium in the eye of a storm.”[114] Lest anyone think that living a life of continual standing in the presence of God is a “heavy, humdrum, and safe” affair, we close with the words of G. K. Chesterton, who understood that the essence of discipleship is to maintain:

the equilibrium of a man behind madly rushing horses, seeming to stoop this way and to sway that, yet in every attitude having the grace of statuary and the accuracy of arithmetic. … It is always simple to fall; there are an infinity of angles at which one falls, only one at which one stands.[115]

This essay is updated adapted from Jeffrey M. Bradshaw. Temple Themes in the Book of Moses. 2014 update ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Publishing, 2014. English: https://archive.org/details/150904TempleThemesInTheBookOfMoses2014UpdatedEditionSReading ; Spanish: http://www.templethemes.net/books/171219-SPA-TempleThemesInTheBookOfMoses.pdf, pp. 159–172.

For a more complete exposition of this theme, see Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, "Standing in the Holy Place: Ancient and modern reverberations of an enigmatic New Testament prophecy." In Ancient Temple Worship: Proceedings of the Expound Symposium, 14 May 2011, edited by Matthew B. Brown, Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, Stephen D. Ricks and John S. Thompson. Temple on Mount Zion 1, 71-142. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014. Reprint, Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 37, 163–236, https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/standing-in-the-holy-place-ancient-and-modern-reverberations-of-an-enigmatic-new-testament-prophecy/. http://www.templethemes.net/publications/04-Ancient%20Temple-Bradshaw.pdf.

For an extensive commentary on Joseph Smith—Matthew, the JST version of Matthew 24 in which standing in the holy place Is enjoined, see Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, The First Days and the Last Days: A Verse-By-Verse Commentary on the Book of Moses and JS—Matthew in Light of the Temple. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2021.

Notes on Figures

Figure 1. Photograph © 2007 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The Art Object: Thomas Cole, American (born in England), 1801-1848, Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, 1828, Oil on canvas, 100.96 x 138.43 cm (39 ¾ x 54 ½ in.), Gift of Martha C. Karolik for the M. and M. Karolik Collection of American Paintings, 1815-1865, 47.1188

Figure 2. http://artmight.com/albums/2011-02-07/art-upload-2/g/Ghiberti-Lorenzo/Ghiberti-Lorenzo-Creation-of-Adam-and-Eve-dt1.jpg (accessed 2 October 2014).

Figure 3. The Harrowing of Hell from the Exultet Roll: Codex Barberini Latinus 592. (f. 4), ca. 1087. Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. Public Domain.

Figure 4. Photograph IMGP1311, 8 December 2009, © Stephen T. Whitlock. British Camp is an iron age fort at the top of Herefordshire Beacon, Malvern Hills, England.

Figure 5. The William Blake Archive. Original in The British Museum.

Figure 6. http://castyournet.files.wordpress.com/2012/09/mt_sinai.gif (accessed 2 October 2014).

Figure 7. The Brooklyn Museum, with the assistance of Deborah Wythe.

Figure 8. The Brooklyn Museum, with the assistance of Deborah Wythe.

Figure 9. Yahoel Lifts the Fallen Abraham, Codex Sylvester, 14th century. Photograph IMGP2167, 26 April 2009, © Stephen T. Whitlock and Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, with special thanks to Carole Menzies and Jennifer Griffiths of the Taylor Bodleian Slavonic and Modern Greek Library. Photograph adapted from P. P. Novickij (Novitskii or Novitsky), Otkrovenie Avraama.

References

Ackroyd, Peter. 1995. Blake. London, England: Vintage, 1999.

Alexander, P. "3 (Hebrew Apocalypse of) Enoch." In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. 2 vols. Vol. 1, 223-315. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983. https://eclass.uoa.gr/modules/document/.

at-Tabataba’i, Allamah as-Sayyid Muhammad Husayn. 1973. Al-Mizan: An Exegesis of the Qur’an. Translated by Sayyid Saeed Akhtar Rizvi. 3rd ed. Tehran, Iran: World Organization for Islamic Services, 1983.

Barker, Margaret. Temple Theology. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), 2004.

Barney, Kevin L., ed. Footnotes to the New Testament for Latter-day Saints. 3 vols, 2007. http://feastupontheword.org/Site:NTFootnotes. (accessed February 26, 2008).

Beale, Gregory K., and Donald A. Carson, eds. Commentary on the New Testament Use of the Old Testament. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2007.

Bednar, David A. 2002. Stand ye in holy places (Talk given during Mothers’ Weekend, BYU Idaho, 22 March). In. https://www.byui.edu/speeches/stand-ye-in-holy-places-2. (accessed March 6, 2010).

Benson, Ezra Taft. The Teachings of Ezra Taft Benson. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1988.

Blake, William. The Illuminated Blake: William Blake’s Complete Illuminated Works with a Plate-by-Plate Commentary. New York City, NY: Dover Publications, 1974.

Bolt, Peter G. The Cross from a Distance: Atonement in Mark’s Gospel. New Studies in Biblical Theology 18, ed. Donald A. Carson. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2004.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. Creation, Fall, and the Story of Adam and Eve. 2014 Updated ed. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014. https://archive.org/download/140123IGIL12014ReadingS.

———. "Standing in the Holy Place: Ancient and modern reverberations of an enigmatic New Testament prophecy." In Ancient Temple Worship: Proceedings of the Expound Symposium, 14 May 2011, edited by Matthew B. Brown, Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, Stephen D. Ricks and John S. Thompson. Temple on Mount Zion 1. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014. Reprint, Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 37, 163–236, https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/standing-in-the-holy-place-ancient-and-modern-reverberations-of-an-enigmatic-new-testament-prophecy/. http://www.templethemes.net/publications/04-Ancient%20Temple-Bradshaw.pdf.

Braude, William G., ed. Pesikta Rabbati: Discourses for Feasts, Fasts, and Special Sabbaths. 2 vols. Yale Judaica Series 28, ed. Leon Nemoy, Saul Lieberman and Harry A. Wolfson. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1968.

Brown, Matthew B. The Gate of Heaven: Insights on the Doctrines and Symbols of the Temple. American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 1999.

Brown, Raymond E. The Death of the Messiah: From Gethsemane to the Grave. 2 vols. The Anchor Bible Reference Library, ed. David Noel Freedman. New York City, NY: Doubleday, 1994.

Brown, S. Kent. "The arrest." In From the Last Supper through the Resurrection: The Savior’s Final Hours, edited by Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Thomas A. Wayment. The Life and Teachings of Jesus Christ 2, 165-209. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2003.

Carasik, Michael, ed. The JPS Miqra’ot Gedolot: Exodus. The Commentator’s Bible. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 2005.

Charlesworth, James H., ed. The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha. 2 vols. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983. (accessed September 20).

Chesterton, Gilbert Keith. 1908. Orthodoxy. New York City, NY: Image Books / Doubleday, 2001.

———. 1910. William Blake. New York City, NY: Cosimo, 2005.

Clark, James R., ed. Messages of the First Presidency. 6 vols. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1965-1975.

Davis, Avrohom, and Yaakov Y. H. Pupko. The Metsudah Midrash Tanchuma, Bamidbar 2. Translated by S. Cassel. Kamenetsky ed. Lakewood, NJ: Israel Book Shop, 2006.

Dennis, Lane T., Wayne Grudem, J. I. Packer, C. John Collins, Thomas R. Schreiner, and Justin Taylor. English Standard Version (ESV) Study Bible. Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles, 2008.

Ephrem the Syrian. ca. 350-363. "The Hymns on Paradise." In Hymns on Paradise, edited by Sebastian Brock, 77-195. Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1990.

Faulring, Scott H., Kent P. Jackson, and Robert J. Matthews, eds. Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible: Original Manuscripts. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2004.

Fletcher-Louis, Crispin H. T. "Some reflections on angelomorphic humanity texts among the Dead Sea Scrolls." Dead Sea Discoveries 7, no. 3 (2000): 292-312. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4193167. (accessed January 23, 2010).

France, Richard Thomas. The Gospel of Matthew. The New International Commentary on the New Testament, ed. Gordon D. Fee. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2007.

Freedman, H., and Maurice Simon, eds. 1939. Midrash Rabbah 3rd ed. 10 vols. London, England: Soncino Press, 1983.

Hayward, Robert. "An Aramaic paradise: Adam and the Garden in the Jewish Aramaic translations of Genesis." Presented at the Temple Studies Group Symposium IV: The Paradisiac Temple—From First Adam to Last, Temple Church, London, England, November 6, 2010.

Jackson, Kent P. The Book of Moses and the Joseph Smith Translation Manuscripts. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Religious Studies Center, 2005. https://rsc.byu.edu/archived/book-moses-and-joseph-smith-translation-manuscripts. (accessed August 26, 2016).

Keener, Craig S. The Gospel of John: A Commentary. 2 vols. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2003.

———. The Gospel of Matthew: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2009.

Koester, Craig R. Symbolism in the Fourth Gospel: Meaning, Mystery, Community. 2nd ed. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 2003.

Kulik, Alexander. Retroverting Slavonic Pseudepigrapha: Toward the Original of the Apocalypse of Abraham. Text-Critical Studies 3, ed. James R. Adair, Jr. Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature, 2004.

Lachs, Samuel Tobias. A Rabbinic Commentary on the New Testament: The Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. Hoboken, NJ: KTAV Publishing House, 1987.

Levine, Baruch A. Leviticus. The JPS Torah Commentary, ed. Nahum M. Sarna and Chaim Potok. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society, 1989.

Martinez, Florentino Garcia, ed. The Dead Sea Scrolls Translated: The Qumran Texts in English 2nd ed. Translated by Wilfred G. E. Watson. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1996.

McConkie, Bruce R. Doctrines of the Restoration: Sermons and Writings of Bruce R. McConkie. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1989.

Milton, John. 1667. "Paradise Lost." In Paradise Lost, Paradise Regained, Samson Agonistes, edited by Harold Bloom, 15-257. London, England: Collier, 1962.

Neusner, Jacob, ed. Genesis Rabbah: The Judaic Commentary to the Book of Genesis, A New American Translation. 3 vols. Vol. 1: Parashiyyot One through Thirty-Three on Genesis 1:1 to 8:14. Brown Judaic Studies 104, ed. Jacob Neusner. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1985.

———, ed. The Mishnah: A New Translation. London, England: Yale University Press, 1988.

Nibley, Hugh W. 1975. The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment. 2nd ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005.

Nickelsburg, George W. E., ed. 1 Enoch 1: A Commentary on the Book of 1 Enoch, Chapters 1-36; 81-108. Hermeneia: A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2001.

Nickelsburg, George W. E., and James C. VanderKam, eds. 1 Enoch: A New Translation. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2004.

Novickij (Novitskii or Novitsky), P. P., ed. Откровение Авраама (Otkrovenīe Avraama [Apocalypse of Abraham]) (Facsimile edition of Silʹvestrovskiĭ sbornik [Codex Sylvester]). Reproduced from RGADA (Russian State Archive of Early Acts, formerly TsGADA SSSR = Central State Archive of Early Acts), folder 381, Printer’s Library, no. 53, folios 164v-186. Общество любителей древней письменности (Obščestvo Li︠u︡biteleĭ Drevneĭ Pis’mennosti [Society of Lovers of Ancient Literature]), Izdaniia (Editions) series, (= OLDP edition, 99:2). St. Petersburg, Russia: Tipo-Lit. A. F. Markova, 1891. Reprint, Leningrad, Russia, 1967. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/012239580. (accessed December 3, 2019).

Oaks, Dallin H. "Preparing for the Second Coming." Ensign 34, May 2004, 7-10.

Ogden, D. Kelly, and Andrew C. Skinner. The Four Gospels. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2006.

Ouaknin, Marc-Alain, and Éric Smilévitch, eds. 1983. Chapitres de Rabbi Éliézer (Pirqé de Rabbi Éliézer): Midrach sur Genèse, Exode, Nombres, Esther. Les Dix Paroles, ed. Charles Mopsik. Lagrasse, France: Éditions Verdier, 1992.

Parry, Donald W. "Temple worship and a possible reference to a prayer circle in Psalm 24." BYU Studies 32, no. 4 (1992): 57-62.

Payne, J. Barton. The Imminent Appearing of Christ. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1962.

Philo. b. 20 BCE. "On Dreams." In Philo, edited by F. H. Colson and G. H. Whitaker. Revised ed. 12 vols. Vol. 5. Translated by F. H. Colson and G. H. Whitaker. The Loeb Classical Library 275, 283-579. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1934.

Rashi. c. 1105. The Torah with Rashi’s Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated. Vol. 2: Shemos/Exodus. Translated by Rabbi Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg. ArtScroll Series, Sapirstein Edition. Brooklyn, NY: Mesorah Publications, 1994.

———. c. 1105. The Torah with Rashi’s Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated. Vol. 1: Beresheis/Genesis. Translated by Rabbi Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg. ArtScroll Series, Sapirstein Edition. Brooklyn, NY: Mesorah Publications, 1995.

Ridderbos, Herman N. The Gospel According to John: A Theological Commentary. Translated by John Vriend. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1997.

Riddle, Chauncey C. "The new and everlasting covenant." In Doctrines for Exaltation: The 1989 Sperry Symposium on the Doctrine and Covenants, 224-45. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1989. https://chaunceyriddle.com/restored-gospel/the-new-and-everlasting-covenant/. (accessed August 7, 2014).

Sarna, Nahum M., ed. Genesis. The JPS Torah Commentary, ed. Nahum M. Sarna. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society, 1989.

———, ed. Exodus. The JPS Torah Commentary, ed. Nahum M. Sarna. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society, 1991.

Shakespeare, William. 1600. "The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark." In The Riverside Shakespeare, edited by G. Blakemore Evans, 1135-97. Boston, MA: Houghton-Mifflin Company, 1974.

Smith, Joseph, Jr. The Words of Joseph Smith. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1980.

———. 1902-1932. History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Documentary History). 7 vols. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1978.

———. 1938. Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1969.

Smith, William. Dr. William Smith’s Dictionary of the Bible: Comprising Its Antiquities, Biography, Geography, and Natural History. 3 vols. Revised ed. New York City, NY: Hurd and Houghton, 1873. http://books.google.com/books?id=wDYXAAAAYAAJ&pg. (accessed February 9).

Stone, Michael E., ed. 1401-1403. Adamgirk’: The Adam Book of Arak’el of Siwnik’. Translated by Michael E. Stone. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Tabory, Joseph. JPS Commentary on the Haggadah: Historical Introduction, Translation, and Commentary. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society, 2008.

Talmage, James E. 1915. Jesus the Christ. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1983.

Townsend, John T., ed. Midrash Tanhuma. 3 vols. Jersey City, NJ: Ktav Publishing, 1989-2003.

Tvedtnes, John A. "Temple prayer in ancient times." In The Temple in Time and Eternity, edited by Donald W. Parry and Stephen D. Ricks, 79-98. Provo, UT: The Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, Brigham Young University, 1999.

———. E-mail message to Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, March 8, 2010.

Wickman, Lance B. "Stand ye in holy places." Ensign 24, November 1994, 82.

Zlotowitz, Meir, and Nosson Scherman, eds. 1977. Bereishis/Genesis: A New Translation with a Commentary Anthologized from Talmudic, Midrashic and Rabbinic Sources 2nd ed. Two vols. ArtScroll Tanach Series, ed. Rabbi Nosson Scherman and Rabbi Meir Zlotowitz. Brooklyn, NY: Mesorah Publications, 1986.

Zornberg, Avivah Gottlieb. Genesis: The Beginning of Desire. Philadelphia, PA: Jewish Publication Society, 1995.

Endnotes

Alma the Younger experienced a fall and a figurative death when he and his companions were visited by an angel, and a rebirth three days later when his mouth was opened and he was again able to stand on his feet: “I fell to the earth; and it was for the space of three days and three nights that I could not open my mouth, neither had I the use of my limbs… But behold my limbs did receive their strength again, and I stood upon my feet, and did manifest unto the people that I had been born of God” (Alma 36:10, 23; cf. King Lamoni and his people in Alma 18:42-43, 19:1-34).

Falling in weakness after a vision of God is a common motif in scripture. Daniel reported that he “fainted, and was sick certain days,” and of a second occasion he wrote: “I was left alone… and there remained no strength in me… and when I heard the voice of his words, then was I in a deep sleep on my face, and my face toward the ground” (Daniel 8:26; 10:8-9). Saul “fell to the earth” during his vision and remained blind until healed by Ananias (Acts 9:4, 17-18). Lehi “cast himself on his bed, being overcome with the Spirit” (1 Nephi 1:7). Of his weakness following the First Vision, Joseph Smith wrote: “When I came to myself again, I found myself lying on my back, looking up into heaven. When the light had departed, I had no strength…” (JS-H 1:20). See also discussion of A. Kulik, Retroverting Apocalypse of Abraham 10:1-4, p. 17 below.

The seer must be rehabilitated and accepted into the divine presence before he can receive his commission. Restoration by an angel becomes a typical feature in visions, where, however, it is the angel whose appearance causes the collapse.

See also Joshua 7:6, 10-13:

6 ¶ And Joshua rent his clothes, and fell to the earth upon his face before the ark of the Lord until the eventide, he and the elders of Israel, and put dust upon their heads .… 10 ¶ And the Lord said unto Joshua, Get thee up; wherefore liest thou thus upon thy face? 11 Israel hath sinned, and they have also transgressed my covenant which I commanded them: for they have even taken of the accursed thing, and have also stolen, and dissembled also, and they have put it even among their own stuff. 12 Therefore the children of Israel could not stand before their enemies, but turned their backs before their enemies, because they were accursed: neither will I be with you any more, except ye destroy the accursed from among you. 13 Up, sanctify the people, and say, Sanctify yourselves against to morrow: for thus saith the Lord God of Israel, There is an accursed thing in the midst of thee, O Israel: thou canst not stand before thine enemies, until ye take away the accursed thing from among you.

By way of contrast, consider Cain’s protest: “Since I am to be a restless wanderer, I cannot stand in one place—that is what banishment form the soil means—I have no place of rest. ‘And I must avoid Your presence’—for I cannot stand before You to pray” (ibid., p. 21).

The idea of five sacred things is encountered in other forms Jewish tradition. For example, Jewish authorities held that five things were lost when Solomon’s temple was destroyed. Both Margaret Barker and Hugh Nibley specifically connect these “five things” to lost ordinances of the High Priesthood (see J. M. Bradshaw, God’s Image 1, pp. 658-660).

Although the tools of an architect are frequently used in medieval depictions of the Creation to portray the geometry of the heavens, seas, and earth, Blake also may have been attracted to this symbol because of his acquaintance with Freemasonry while he was an apprentice engraver (P. Ackroyd, Blake, p. 377). An associate of Blake said that the artist saw the vision of this image hovering “at the top of his staircase; and he [was] frequently… heard to say, that it made a more powerful impression upon his mind than all he had ever been visited by” (ibid., p. 378). He worked and reworked this image continually, reportedly returning to it for a final effort in the last hours before his death.

R. Huna said in the name of R. Aha (Aba?): The earth and all the inhabitants thereof were about to be dissolved; but then because of the I, (the “I” which begins the Ten Commandments and hence stands for Israel’s acceptance of God and the Torah, it stood firm], as the verse concludes, I caused the pillars of it to stand firm (Psalm 75:4). Long ago the world might have dissolved and disappeared. Had not Israel stood before Mount Sinai and said: All that the Lord hath said we will do and obey (Exodus 24:7), the world might have already reverted to chaos. And who made the world stand firm? I [anokhi] made the pillars of it stand firm, because of the merit Israel acquired in heeding “I [anokhi] am the Lord thy God.” (W. G. Braude, Rabbati, 21:21, p. 451)

Zornberg comments on the passage above as follows:

On a first reading, it seems that what saves the world from decomposing is God and His Law, which the people obediently accept. (“It is I who gives solidity to the world, through my commandments, encoded in the opening word of the Ten Commandments, anokhi—I.…”) But there is another possible—and compelling reading. Here, the anokhi, which gives substance and coherence to reality, is the “I” of human beings. Rashi reads the prooftext, the verse from Psalms (75:4), in just this unexpected way: “’It is I who keeps its pillars firm’—when I said, ‘We shall do and we shall listen.’” The people are responsible for the “I” that “fixes,” that congeals a dissolving reality. The world is saved by a human affirmation, a human “standing at Sinai,” which halts the process of disintegration. (A. G. Zornberg, Genesis, p. 28)

“Here I stand there before you, on the rock in Horeb” (Exodus 17:6), which means, “this I, the manifest, Who am here, am there also, am everywhere, for I have filled all things. I stand ever the same immutable, before you or anything that exists came into being, established on the topmost and most ancient source of power, whence showers forth the birth of all that is.…” And Moses too gives his testimony to the unchangeableness of the deity when he says “they saw the place where the God of Israel stood” (Exodus 24:10), for by the standing or establishment he indicates his immutability. But indeed so vast in its excess is the stability of the Deity that He imparts to chosen natures a share of His steadfastness to be their richest possession. For instance, He says of His covenant filled with His bounties, the highest law and principle, that is, which rules existent things, that this god-like image shall be firmly planted with the righteous soul as its pedestal… And it is the earnest desire of all the God-beloved to fly from the stormy waters of engrossing business with its perpetual turmoil of surge and billow, and anchor in the calm safe shelter of virtue’s roadsteads. See what is said of wise Abraham, how he was “standing in front of God” (Genesis 18:22), for when should we expect a mind to stand and no longer sway as on the balance save when it is opposite God, seeing and being seen?… To Moses, too, this divine command was given: “Stand here with me” (Deuteronomy 5:31), and this brings out both the points suggested above, namely the unswerving quality of the man of worth, and the absolute stability of Him that IS. (modified by Fletcher-Louis from Philo, Dreams, 2:32, 221-2:33, 227, pp. 543, 545).

Fletcher-Louis comments on parallels between Philo, 4Q377 from Qumran, and the Pentateuch:

Like Philo, 4Q377 is working with Deuteronomy 5:5, the giving of the Torah, and perhaps Exodus 17:6. Both texts think standing is a posture indicative of a transcendent identity in which the righteous can participate and of which Moses is the pre-eminent example. With the stability of standing is contrasted the corruptibility of motion, turmoil and storms, which is perhaps reflected in the tension between Israel’s “standing” (lines 4 and 10) and her “trembling” (line 9) before the Glory of God in the Qumran text. Whether this and other similar passages in Philo (cf. esp. Sacr. 8-10; Post. 27-29) are genetically related to 4Q377 is not certain, but remains a possibility. (C. H. T. Fletcher-Louis, Reflections, p. 304)

Only John mentions the “garden” (John 18:1, 26; 19:41); gardens often were walled enclosures. Perhaps John alludes to the reversal of the Fall (cf. Romans 5:12-21) in the Garden of Eden (Genesis 2:8-16), but John nowhere else uses an explicit Adam Christology, and the Septuagint uses [kepos] for the Hebrew’s Garden of Eden only in Ezekiel 36:35 (and there omits mention of Eden, normally preferring [paradeisos]), rendering the parallel less likely. (John could offer his own free translation, but the proposed allusion, in any case, lacks adequate additional support to be clear.) The Markan line of tradition suggests that perhaps olive trees grew nearby; its name, Gethsemane, suggests an olive press and hence was probably the name for an olive orchard at the base of Mount Olivet. In the Septuagint, a [kepos] appears as an agricultural unit alongside olive groves and vineyards (e.g., 1 Kings 21:2; 2 Kings 5:26; Song of Solomon 6:11; Amos 4:9, 9:14). If the garden has symbolic import (which it might not), it may connect Jesus’ arrest with his tomb and the site of his resurrection (John 19:41) or perhaps allude to the seed that must die (John 12:24) or to the Father’s pruning (John 15:1). (C. S. Keener, John, p. 1077)

Judas’ defection is accompanied by his alliance with the circle of Jesus’ opponents. When Jesus was met by soldiers and police in the garden, the evangelist points out that Judas “was standing with them” (John 18:5). The detail confirms that Judas is no longer one of Jesus’ followers but has become one of his foes. His group membership visibly changes… By standing with them, Judas shows that he belongs to those who are swayed by the demonic ruler of this world. (C. R. Koester, Symbolism, p. 74)

God did not cause the evil of betrayal but turned it in a direction that ultimately served his saving purposes. When Judas is introduced in John 6:70, he is called “a devil.” The evangelist does not speculate about the reasons for Judas becoming a devil, but accepts the evil as a given. The question is: Given the presence of evil, whatever its origin, how will God and Christ deal with it? As the story unfolds, Judas is a devil, but Jesus chooses him along with the other disciples (John 6:70); the devil puts betrayal into Judas’ heart, yet Jesus washes his feet (John 13:1-11). Jesus gives Judas a piece of bread, only to have Satan enter; so Jesus gives the betrayer permission to leave (John 13:26-30). Rather than causing the evil, Christ meets evil with gracious actions, finally turning the evil toward God’s saving ends. (C. R. Koester, Symbolism, p. 75)

Jesus’ self-identification in 18:5, “I am,” probably has connotations of deity… This is strongly suggested by the soldiers’ falling to the ground in 18:6, a common reaction to divine revelation (see Ezekiel 1:28, 44:4; Daniel 2:46, 8:18, 10:9; Acts 9:4, 22:7, 26:14; Revelation 1:17, 19:10, 22:8). This falling of the soldiers is reminiscent of certain passages in Psalms (see Psalms 27:2, 35:4; cf. 56:9; see also Elijah’s experience in 2 Kings 1:9-14). Jewish literature recounts the similar story of the attempted arrest of Simeon (Genesis Rabbah 91:6). The reaction also highlights Jesus’ messianic authority in keeping with texts such as Isaiah 11:4 (cf. 2 Esdras 13:3-4). (G. K. Beale et al., NT Use of the OT, John 18-19, p. 499)

OT antecedents for this reaction have been proposed, e.g., Psalm 56:10(9): “My enemies will be turned back… in the day when I shall call upon you”; Psalm 27:2: “When evildoers come at me… my foes and my enemies themselves stumble and fall…”; Psalm 35:4: “Let those be turned back… and confounded who plot evil against me.” Falling down (piptein) as a reaction to divine revelation is attested in Daniel 2:46, 8:18; Revelation 1:17; and that is how John would have the reader understand the reaction to Jesus’ pronouncement. Piptein chamai is combined with the verb “to worship” in Job 1:20. No matter what one thinks of the historicity of this scene, it should not be explained away or trivialized. To know or use the divine name, as Jesus does, is an exercise of awesome power. In Acts 3:6 Peter heals a lame man “in the name of Jesus of Nazareth,” i.e., by the power of the name that Jesus has been given by God; and “there is no other name under heaven among human beings by which we must be saved.” Eusebius (Praeparatio Evangelica 9:27:24-26 in J. H. Charlesworth, Pseudepigrapha, 2:901; GCS 43.522) attributes to Artapanus, who lived before the 1st century BC, the legend that when Moses uttered before Pharaoh the secret name of God, Pharaoh fell speechless to the ground (R. D. Bury, ExpTim 24 (1912-13), 233). That legend may or may not have been known when John wrote, but it illustrates an outlook that makes John’s account of the arrest intelligible.

This same Jesus will say to Pilate, “You have no power over me at all except what was given to you from above” (John 19:11). Here he shows how powerless before him are the troops of the Roman cohort and the police attendants from the chief priests—the representatives of the two groups who will soon interrogate him and send him to the cross. Indeed, an even wider extension of Jesus’ power may be intended. Why does John suddenly, in the midst of this dramatic interchange, mention the otiose presence of Judas, “now standing there with them was also Judas, the one who was giving him over” (John 18:5)? John 17:12 calls Judas “the son of perdition,” a phrase used in 2 Thessalonians 2:3-4 to describe the antichrist who exalts himself to the level of God. Is the idea that the representative of the power of evil must also fall powerless before Jesus? I have already pointed out a close Johannine parallel to the Mark/Matthew saying about the coming near of the one who gives Jesus over, namely, John 14:30: “For the Prince of this world is coming.” In John 12:31, in the context of proclaiming the coming of the hour (John 12:23) and of praying about that hour (John 12:27), Jesus exclaims, “Now will the Prince of this world be driven out” (or “cast down,” a textual variant; see also 16:11). (R. E. Brown, Death, 1:261-262)

Keener offers additional precedents for the “involuntary prostration” of Jesus’ enemies:

Other ancient texts report falling backward in terror—for instance, fearing that one has dishonored God (Sipra Sh. M.D. 99:5:12; cf. perhaps 1 Samuel 4:18). (C. S. Keener, John, p. 1082)

Talbert, John, 233, adds later traditions in which priests fell on their faces when hearing the divine name (b. Qidd. 71a; Eccl. Rab. 3:11, S3). (ibid., p. 1082 n. 124)

Shortly before his crucifixion, the Savior took the twelve apostles, and perhaps others, with Him to the Garden of Gethsemane, which is located on the western slope of the Mount of Olives. When they had entered into the garden area, the Lord instructed the majority of His disciples to wait for Him while He took Peter, James, and John further into the Garden. Then, at some unspecified location, Christ told Peter, James, and John to stay where they were while He “went a little further” into Gethsemane by Himself (see Matthew 26:30-39; Mark 14:26-36). It was in this third area of the Garden that the Savior was visited and strengthened by an angel and where He shed His sacrificial blood (see JST Luke 22:43-44). This pattern is intriguing because it seems to match the tripartite division of the people during the Mount Sinai episode (Ground Level—Israelites, Half-Way—Seventy Elders, Top—Moses) and the tripartite division in the temple complex (Courtyard—Israelites, Holy Place—Priests, Holy of Holies—High Priest). It was, of course, in the Holy of Holies on the Day of Atonement that the final rite was performed to purge the sins of the Israelites with sacrificial blood (see Leviticus 16:15).

Jesus clarifies that the complete fulfillment of Daniel’s prophecy will be found in (1) the Roman destruction of the temple in AD 70 and (2) the image of the Antichrist being set up in the last days (cf. 2 Thessalonians 2:4: Revelation 13:14). (L. T. Dennis et al., ESV, Matthew 24:15n., p. 1873)

Though such an event may indeed be part of what is being prophesied by JS-Mathew 1:32, the desolation predicted in Doctrine and Covenants 43:31-33 appears to be of much more extensive in scope.