This series is cross-posted with the permission of Book of Mormon Central

from their website at Pearl of Great Price Central

Audio Player

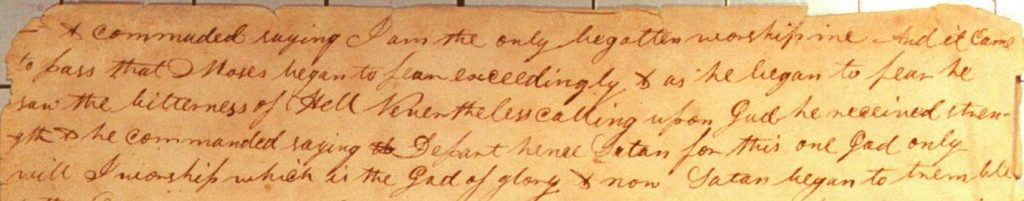

Joseph Smith Bible Translation (JST), Old Testament Manuscript 1, p. 2 (detail). In Moses 1:20, Moses calls upon God and receives strength. This event is the hinge point of a concentric chiasmus arrangement for the entire chapter.

This Essay examines the ancient literary form of chiasmus within Moses 1. Chiasmus includes “several types of inverted parallelisms, short or long, in which words first appear in one order and then in the opposite order.”[1]

In contrast to earlier discussions, recent studies of chiasmus have increasingly focused on its purpose and function. Scholars have relied on chiasmus to identify textual boundaries, to account for repetitions within a literary unit, to discover a composition’s main theme and as a marker for textual unity.

Here, we will focus on two of these aspects: First, we will look at chiasmus as a structuring device and second, as an indicator of textual units.

Chiasmus as a Structuring Device

Concentric structuring. Moses 1 can be structured as three scenes arranged in a concentric pattern. Moses’ face-to-face encounters with God provide a frame for the confrontation between Moses and Satan:

A Moses in the presence of God (1:1-11)

B Confrontation between Moses and Satan (1:12-22)

A′ Moses in the presence of God (1:23-2:1)

The contest against Satan completes a tripartite structure which is folded between the ascent accounts. Satan’s sudden arrival, temptation of Moses and expulsion is a natural hinge for the following concentric arrangement:

Moses 1:1-2:1

A The word of God, which he spoke unto Moses upon an exceeding high mountain (1) B Endless is God’s name (3) C God’s work and his glory (4) D The Lord has a work for Moses E Moses is in the similitude of the Only Begotten (6) F Moses beholds the world and the ends thereof (7-8) G The presence of God withdraws from Moses (9) H Man, in his natural strength, is nothing (10) I Moses beheld God with his spiritual eyes (11) J Satan came tempting him (12) K Moses’ response to Satan (13-15) L Moses commands Satan to depart (16-18) M Satan ranted upon the earth (19) N Moses began to fear O Moses called upon God N′ Moses received strength (20) M′ Satan began to tremble and the earth shook L′ Moses cast Satan out in the name of the Only Begotten (21) K′ Satan cried with weeping and wailing J′ Satan departs from Moses (22) I′ Moses lifted up his eyes unto heaven (23-24) H′ Moses is made stronger than many waters G′ Moses beheld God’s glory again (25) F′ Moses is shown the heavens and the earth (27-31) E′ Creation by the Only Begotten (32-33) B′ God’s works and words are endless (38) C′ God’s work and his glory (39) D′ Moses to write the words of God (40-41) A′ The Lord spoke unto Moses concerning the heaven and earth (Moses 2:1)

The author’s use of chiasmus as a structuring device is significant on many levels. Most importantly, it uses the center of the structure to highlight the theme of this chapter. Moses calling upon God and being strengthened by him is the turning point. After that, everything changes. Moses is able to overcome this trial by Satan and then return to the presence of the Lord to speak with him face to face. The instruction and blessings Moses receives at the end of the chapter are greater than what he received at the beginning of the chapter.[2]

The structure of the chapter dictates that the second half of the chapter is very closely related to the first half. The parallels are striking. The two divine encounters of the author tightly frame this epic battle with Satan at the center of the chiasm and the turning point of the story being Moses calling upon God and being strengthened. Dan Belnap elaborates that, “The differences between the two encounters will reflect the new understandings of the vision Moses gains through his confrontation with the adversary.”[3]

One of Nils Lund’s laws of chiasmus demonstrates that the center of the chiasm often has a parallel theme in the outer portion of the arrangement as well.[4] The center of the arrangement has Moses being strengthened. This theme of strength occurs in verse 10 and later in verse 25. Perhaps the most interesting parallel is the pairing with the oft quoted Moses 1:39, where God’s work and glory is explained, with its counterpart in verse 5. Verse 39, when seen as an expansion of verse 5, gives God’s work and glory a cosmic context that places humankind as a higher priority than all the rest of creation.

It is also important to note that the boundaries of this literary unit go beyond the current chapter limits of our published Book of Moses and stretch into chapter two. The significance of this will be discussed below.

Smaller chiastic structures. Wayne Larsen[5] has proposed that the description of God’s “work and glory” in verse 39 forms a chiastic bookend with God’s statement in Moses 1:31-32: “For mine own purpose have I made these things. Here is wisdom and it remaineth in me. And by the word of my power, have I created them, which is mine Only Begotten Son, who is full of grace and truth.”

Moses 1:31-39

A God’s purpose (verse 31)

B Worlds without number / worlds pass away (32-34)

C Only an account of this earth (35)

C’ Moses accepts an account of only this earth (36)

B’ Heavens cannot be numbered / heavens pass away (37-38)

A’ God’s purpose (39)

Small gems like this indicate the careful way in which the English text was crafted.

Bipartite structuring. One of the strange things about the detailed structure of Moses 1 as a whole is a seemingly intrusive verse near the middle of the chapter that commands Moses not to share certain parts of his account with unbelievers. However, once the bipartite structure of the chapter is recognized, the seeming intrusion makes perfect sense.

Moses 1:1-41

A Moses is caught up to see God (1) B God declares himself as the Almighty (3) C God is without beginning of days or end of years (3) D Moses beholds the world (7) E Moses beholds the children of men (8) F Moses sees the face of God (11) G Moses to worship the Only Begotten (17) H Moses bore record of this, but due to wickedness, it shall not be had among the children of men (23) A’ Moses beholds God’s glory (24-25) B’ God declares himself the as Almighty (25) C’ God to be with Moses until the end of his days (26) D’ Moses beholds the earth (27) E’ Moses beholds the earth’s inhabitants (28) F’ Moses sees the face of God (31) G’ Creation through the Only Begotten (33) H’ Moses to write the words of God, but they shall be taken away (41)

Guiding the reader. The use of chiasmus in Moses 1 also serves as a rhetorical purpose to guide the reader along the journey the narrator has created. This structural form is appropriate for when the flood rises and falls, for times when the first shall be last and the last shall be first, and when things that are lost are to be restored. Or for when a prophet is caught up to God and then returned. The chiastic pattern rhetorically reflects the narrative direction of the unit.

Consider this example from the first ascent in the first verses of Moses 1. Here the author ends the ascent in a mirror image of the way it began:

Moses was caught up into an exceedingly high mountain

Moses saw God face to face, and he talked with him

The glory of God was upon Moses

Moses could endure his presence. (Moses 1:1-2)The presence of God withdrew from Moses.

God’s glory was not upon Moses.

Moses was left unto himself.

Moses fell unto the earth. (Moses 1:9)

The ending in verse nine mirrors the introduction in verses 1-2. This gives the audience an abrupt ending to the ascent, almost as if the reader tripped and fell down these steps, not unlike Moses falling to the earth. The phrases used by the author in verse nine are abrupt and to the point, hurrying the pace of the narrative.

With such rhetorical effect in the text, it is easy to see that Hugh Nibley has correctly referred to Moses 1 as a “literary tour de force”.[6]

Chiasmus as a Tool in Text Criticism

Another way that chiasmus can be used is an indicator of textual unity. If a structural device is employed in the text, it can be argued that the author or editor who was responsible for the first part of the text was also responsible for the rest of the structure. If the additions by the JST are found embedded in such structures, it is reasonable to view those as a restoration of a pre-existing text.

Consider this example from the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible (JST). In Mark 9:13, Jesus answers a question from Peter, James and John about Elijah (Elias in the KJV). The additions made in the JST continue the response of the Savior with a few additional details. Note that the text added in the JST revision of the verses is italicized.

Mark 9:13 (JST)

But I say unto you

A that Elias is indeed come

B and they have done unto him

whatsoever they listed

C as it is written of him

C’ and he bore record of me

B’ and they received him not.

A’ Verily, this was Elias.

The fact that this addition to the text makes a complete chiastic unit is evidence that the added material may be a restoration of a once original text. The presence of the chiastic structure fits the observations of Francis I. Anderson who noted, “Some editor has put together scraps of … the same story with scissors and paste, and yet has achieved a result which from the point of view of discourse grammar, looks as if it has been made out of whole cloth.”[7]

Once the chiastic structure of the verse is recognized, the addition by the Prophet Joseph Smith to the New Testament text appears to read as whole cloth.

This notion of narrative structures in the text as indicators of a prophetic restoration has application to Moses 1. The end of Moses 1 contains an injunction from the Lord to Moses to write his words, which is carried through to Moses 2. Kent Jackson notes that in the transition between chapters, “[the words of Moses 2] do not give the impression of having been written to stand at the head of a new document, but to continue the texts that precede them.”[8]

This flow of the words invites a look for literary features. Here we find a connecting link between these two separate revelations in the form of a small chiasm.

[9]

The earlier revelation of Moses 1 is presented in regular type while the separate revelation that begins the next chapters (Moses 2) is in italics.

Moses 1:40-2:1

A …this earth upon which thou standest B write the words which I shall speak. (40) C And in a day when the children of men D shall esteem my words as naught E and take many of them from the book which thou shall write, F behold, I will raise up another F′ like unto thee E′ and they shall be had again C′ among the children of men D′ as many as shall believe. (41) B′ …write the words which I speak A′ …and the earth upon which thou standest. (2:1)

Note that verse 42 has been left out of the arrangement as it is a parenthetical aside from the Lord to the Prophet Joseph Smith and is not part of the vision itself.[10]

The presence of chiasmus in these verses link these two revelations together suggesting a deliberate textual unit. The words “earth upon which thou standest” act as an inclusio demarcating the limits of the segment.

The use of chiasmus to demonstrate the fabric of the text and show possible tampering has also been used cautiously by Bart D. Ehrman. He wisely notes: “Such probabilities cannot be overlooked, even if they do not prove decisive in and of themselves.”[11]

If a narrative structure contains elements from both the JST and the extant biblical text, it strongly suggests a textual unity between the two.[12]

Conclusion

The study of chiasmus in Moses chapter 1 reveals a carefully constructed literary masterwork.

In addition to testifying to the antiquity of Moses 1, chiasmus serves as an important tool for understanding the textual fabric of the Book of Moses and may indicate passages where the JST additions are carefully woven into the biblical text.

Further Reading

Bowen, Matthew L. "‘And They Shall Be Had Again’: Onomastic Allusions to Joseph in Moses 1:41 in View of the So-called Canon Formula." Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 32 (2019): 297-304. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/and-they-shall-be-had-again-onomastic-allusions-to-joseph-in-moses-141-in-view-of-the-so-called-canon-formula/. (accessed July 20, 2020).

Johnson, Mark J. "The lost prologue: Reading Moses Chapter One as an Ancient Text." Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 36 (2020): 145-86. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/the-lost-prologue-reading-moses-chapter-one-as-an-ancient-text/. (accessed June 5, 2020).

Rappleye, Neal. "Chiasmus criteria in review." BYU Studies Quarterly 59, no. Supplement containing the papers from the Chiasmus Jubilee Conference at BYU, August 15-16, 2017, sponsored by Book of Mormon Central and BYU Studies. John w. Welch and Donald W. Parry, eds. (2020): 289-309. https://byustudies.byu.edu/issue/59-2-Supplement. (accessed August 17, 2020).

Notes on Figures

Figure 1. S. H. Faulring, et al., JST Electronic Library, OT 1-2 (Moses 1:19b-36), Moses 1:19b-21a.

References

Andersen, Francis I. The Sentence in Biblical Hebrew. The Hague, Netherlands: Mouton, 1974.

Belnap, Daniel. "‘Where is thy glory’: Moses 1, the nature of truth, and the plan of salvation." Religious Educator 10, no. 2 (2009): 163-79. https://rsc.byu.edu/sites/default/files/pub_content/pdf/Where_Is_Thy_Glory_Moses_1_the_Nature_of_Truth_and_the_Plan_of_Salvation.pdf. (accessed August 17, 2020).

Berman, Joshua A. Inconsistency in the Torah: Ancient Literary Convention and the Limits of Source Criticism. New York City, NY: Oxford University Press, 2017. https://www.scribd.com/document/439395392/Joshua-A-Berman-Inconsistency-in-the-Torah-Ancient-Literary-Convention-and-the-Limits-of-Source-Criticism-2017-Oxford-University-Press. (accessed August 8, 2020).

Bowen, Matthew L. "‘And They Shall Be Had Again’: Onomastic Allusions to Joseph in Moses 1:41 in View of the So-called Canon Formula." Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 32 (2019): 297-304. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/and-they-shall-be-had-again-onomastic-allusions-to-joseph-in-moses-141-in-view-of-the-so-called-canon-formula/. (accessed July 20, 2020).

Calabro, David. "Joseph Smith and the architecture of Genesis." In The Temple: Ancient and Restored. Proceedings of the 2014 Temple on Mount Zion Symposium, edited by Stephen D. Ricks and Donald W. Parry. Temple on Mount Zion 3, 165-81. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2016. https://www.academia.edu/37488023/Joseph_Smith_and_the_Architecture_of_Genesis. (accessed August 25, 2020).

Ehrman, Bart D. The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Faulring, Scott H., and Kent P. Jackson, eds. Joseph Smith’s Translation of the Bible Electronic Library (JSTEL) CD-ROM. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 2011.

Jackson, Kent. "The visions of Moses and Joseph Smith’s Bible translation." In “To Seek the Law of the Lord”: Essays in Honor of John W. Welch, edited by Paul Y. Hoskisson and Daniel C. Peterson, 161-69. Orem, UT: The Interpreter Foundation, 2017. Reprint, Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 40(2020), 89–98. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/the-visions-of-moses-and-joseph-smiths-bible-translation/.

Lund, Nils W. Chiasmus in the New Testament. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1942.

Nibley, Hugh W. "To open the last dispensation: Moses chapter 1." In Nibley on the Timely and the Timeless: Classic Essays of Hugh W. Nibley, edited by Truman G. Madsen, 1-20. Provo, UT: BYU Religious Studies Center, 1978. https://archive.bookofmormoncentral.org/content/open-last-dispensation-moses-chapter-1. (accessed August 21, 2020).

Rappleye, Neal. "Chiasmus criteria in review." BYU Studies Quarterly 59, no. Supplement containing the papers from the Chiasmus Jubilee Conference at BYU, August 15-16, 2017, sponsored by Book of Mormon Central and BYU Studies. John W. Welch and Donald W. Parry, eds. (2020): 289-309. https://byustudies.byu.edu/issue/59-2-Supplement. (accessed August 17, 2020).