An Old Testament KnoWhy[1]

Gospel Doctrine Lesson 11:

“How Can I Do This Great Wickedness?”

(Genesis 34; 37-39) (JBOTL11A)

Figure 1. Jacques Joseph Tissot (1836-1902): Joseph Converses with Judah, His Brother

Question: Immediately after telling us that Joseph was sold as a slave in Egypt, Genesis suddenly shifts our attention to the story of Judah and Tamar. Why is Joseph’s story abruptly interrupted at such a crucial point in the narrative? Why are the stories of Joseph and Judah intertwined throughout?

Summary: The story of Judah and Tamar in Genesis 38 “seems to be out of place,”[2] with some scholars going so far as to dismiss it entirely as “an extraneous fragment.”[3] But closer examination of this story demonstrates that it was placed where it was for good reason — and with great skill and subtlety. Lacking this important interlude, we might think that the final chapters of Genesis were concerned only with the rise of Joseph in Egypt and how, through God’s hand and his faithfulness, Jacob’s family was saved from death by famine. In fact, however, the inspired editor of Genesis has deliberately interwoven the stories of Joseph and Judah. In doing so, he demonstrates that their trials and tests were part of a divine tutorial designed to prepare them to become models for and eventually leaders of their brothers. Later, Joseph and Judah would become the ancestors of the most prominent tribes of Israel’s northern and southern dominions respectively, thus fulfilling (in part) God’s promises to Abraham: “I will make nations of thee, and kings shall come out of thee.”[4]

The Know

Readers of Genesis are sometimes jarred when they encounter the sudden shift the end of chapter 37. At that point in the story of Joseph, the seemingly unrelated chapter about Judah and Tamar inserted as chapter 38 seems intrusive.[5] The interruption occurs “at a crucial dramatic spot, and is not chronologically fully consistent with it ([Judah] ages considerably; then we return to [Joseph] as a seventeen-year-old). … [However, a closer look reveals that t]he narrator has woven Chapters 38 and 37 together with great skill.” [6] The careful reader will notice significant parallels in the stories of Joseph and Judah. For example, in both chapter 37 and 38 “a man is asked to ‘recognize’ objects,” [the kid of a goat] is used, and … a brother is betrayed.”[7] Finally, when Genesis shifts our attention back from Judah to Joseph (Genesis 39), “we move in pointed contrast from a tale of exposure through sexual incontinence [in the case of Judah and Tamar] to a tale of seeming defeat and ultimate triumph through sexual continence — Joseph and Potiphar’s wife.”[8] All this is convincing evidence that the story of Judah and Tamar was placed in its current sequence for a reason.[9]

But what is that reason?

To find out, let’s take a closer look at the story as a whole.

Judah and Joseph’s Intertwined Journeys

Judah’s three older brothers disqualify themselves as leaders.

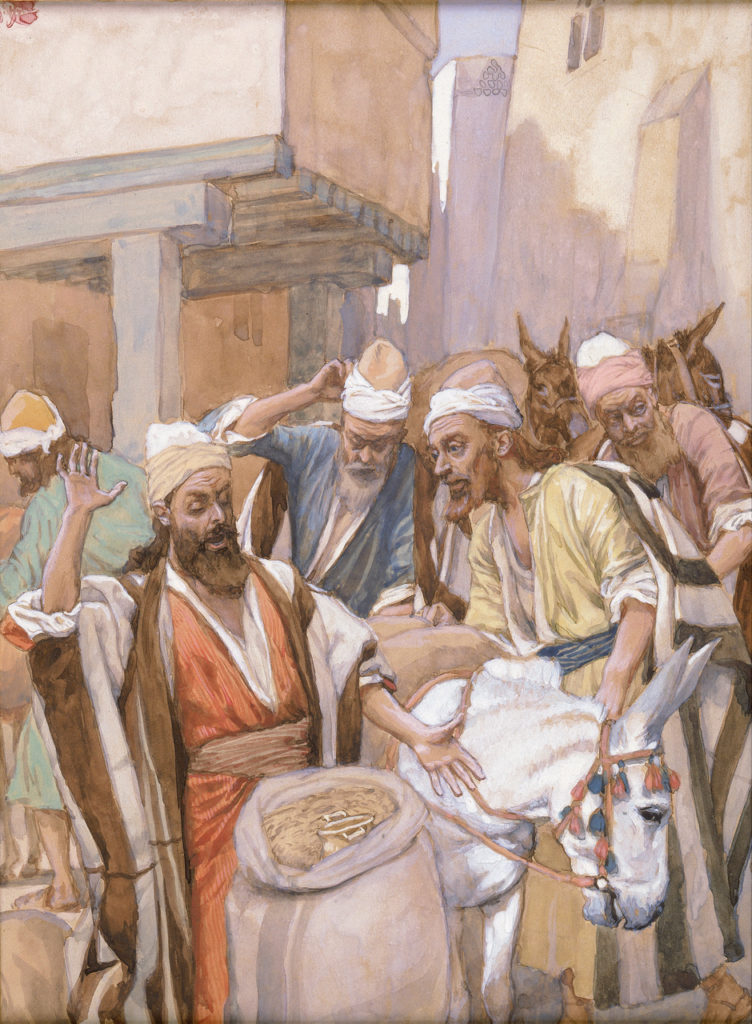

Figure 2. Jacques Joseph Tissot (1836-1902):

Joseph Is Sold Into Egypt

Judah’s rise as a leader among the sons of Leah is a natural aftermath to the disgraceful actions of his three older brothers, Reuben, Simeon, and Levi. In each case, their actions had sprung from a context of sexual sin. Reuben had disqualified himself for the birthright when he “went and lay with Bilhah his father’s concubine.”[10] As a result, his father’s later blessing characterized him as “unstable as water,” and stated his fate starkly: “thou shalt not excel.”[11] Afterward, when the children of Israel began to spread out and occupy the land of Canaan under the leadership of Joshua, Reuben’s tribe dwindled into insigificance.

After Jacob’s only daughter Dinah was defiled by Shechem the Hivite, her father had tried to transform an ugly situation into something more honorable by consenting to a marriage, conditioned on the willingness of the men of the village to undergo circumcision.[12] But in contrast to Jacob’s graciousness and desire to bless the people of Shechem, Simeon and Levi “were very wroth.”[13] Defying the formal agreement their father had made, Simeon and Levi “took each man his sword, and came upon the city boldly, and slew all the males.”[14] Afterward, Jacob reproached them, saying “Ye have troubled me to make me to stink among the inhabitants of the land.”[15] The later benediction they received from their father was really a malediction — it addressed Simeon and Levi jointly with these words: “Cursed be their anger, for it was fierce; and their wrath, for it was cruel: I will divide them in Jacob, and scatter them in Israel.”[16]

Joseph and Judah are separated in order to prepare them for their future callings. As a consequence of these episodes, God intended that Joseph and Judah should be “separate from [their] brethren.”[17] Being “separated” (or we might even say “set apart”) from their brothers allowed them to develop as leaders. Indeed, Bible scholar Nahum Sarna translates the Hebrew term given as “separate” in the King James Version as “leader.” This reading hints at the eventual destiny of the posterity of Joseph and Judah as kings, since the “Hebrew nazir may here be ‘one who wears the nezer,’ the symbol of royal power, as in 2 Samuel 1:10 and 2 Kings 11:12.”[18]

Although the term “separate” is used explicitly only for Joseph, the biblical record clearly signals the parallel nature of the two brothers’ journeys. While Genesis 38:1 says that “Judah went down from his brethren,”[19] the first verse of Genesis 39 reads that “Joseph was brought down to Egypt.”[20] Robert Alter sees the commonality in the verb root in the opening of both stories as having the purpose of “connecting this separation of [Judah] from the rest with Joseph’s.”[21]

In the Bible’s description of these parallel journeys, “more than geography seems to be meant.”[22] Indeed, In Judah’s case, it portends a thorough reform of his character. In the process he will change from a hardened, selfish individual to a tender-hearted, selfless father and brother. So effective will be the change that by chapter 44 he will be ready to “[offer] himself in place of Benjamin for their father’s sake.”[23]

Judah’s Trials (Genesis 38)

Judah loses two sons. Chapter 37 closes with Jacob “bemoaning what he believed to be the death of his son. By way of contrast, Genesis 38 begins with Judah fathering three sons, one after another, recorded in breathless pace.”[24] But Judah’s seeming good fortune quickly turns to grief. No sooner do we learn of the oldest son Er’s marriage to Tamar than we hear of his death because he was “wicked in the sight of the Lord.”[25]

Afterward, Judah reminds his second son, Onan, of his duty to marry his elder brother’s widow. “It was a well-known practice in biblical times that if a man died without leaving an heir, it was the obligation of his nearest of kin (usually his brother) to marry the widow and sire a son — who would then bear the name of the deceased man”[26] However, as the Joseph Smith Translation (JST) tells us: “when [Onan] married his brother’s wife, … he would not lie with her, lest he should raise up seed unto his brother.”[27] The jealousy and rivalry between the sons of Jacob is continued in Judah’s posterity. Perhaps Onan refused out of greed, knowing that Er’s property might revert to him if Tamar were never blessed to bear an heir. In any case, Onan’s actions “displeased the Lord: wherefore he slew him also.”[28]

Judah seems unmoved by his two elder sons’ deaths. In contrast to Jacob’s deep grief “over the imagined death of one son, [his] reaction to the actual death in quick sequence of two sons is passed over in complete silence: he is only reported in delivering pragmatic instructions having to do with the next son in line,”[29] Shelah.

Judah’s deception and Tamar’s counter-deception. Having lost two sons to Tamar already makes her, in Judah’s eyes, a bad risk for his last son Shelah. So he takes a practical precaution:

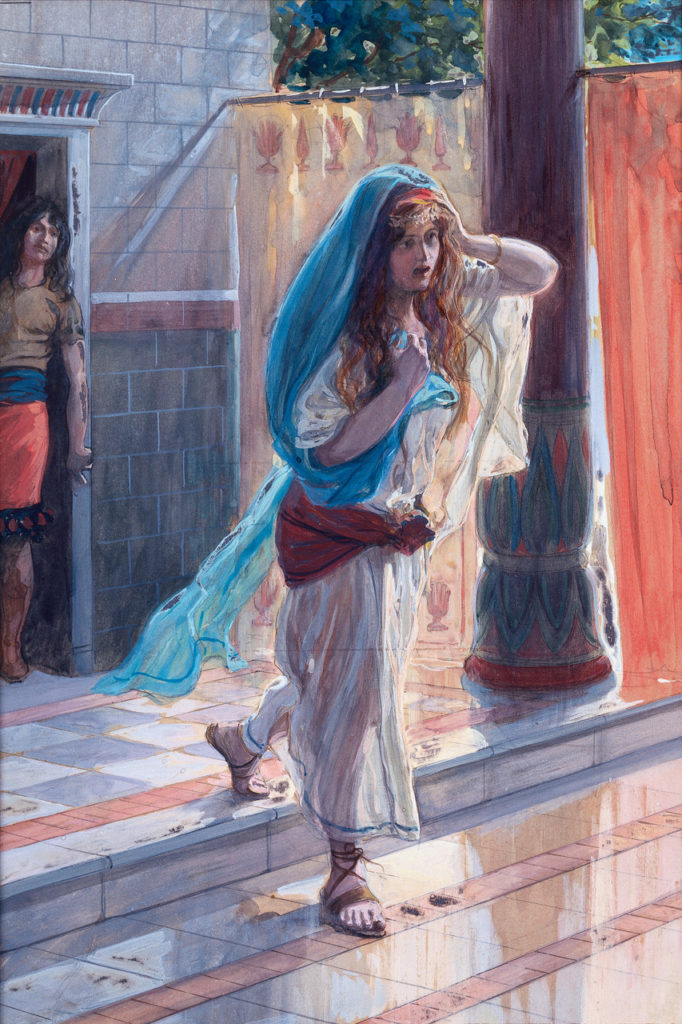

Figure 3. Jacques Joseph Tissot (1836-1902):

The Desolation of Tamar

Judah deceives Tamar by seeming to promise Shelah’s services when he grows up, when in fact he is expelling her from his household to her father’s house. … He instructs her to remain a widow, outside of his care. Tamar is deceived, unaware of Judah’s intentions. … The tables turn when Tamar recognizes the truth [that Judah never intended to give her to Shelah] some time later and plans a counter-deception.[30]

Tamar’s counter-deception succeeds and ultimately makes her a mother through her father-in-law Judah. Pointedly, each incident in the unfolding of events repeatedly confirms Judah’s callous disregard for others. When Tamar’s actions are unmasked and Judah pronounces stern judgment on her wrongdoing (“Bring her forth, and let her be burnt”[31]), a grave dishonor in which he himself was unwittingly the more guilty party, his response reveals a spirit of “naked unreflective brutality.”[32] In Hebrew, his “deadly instructions” are uttered swiftly in two words: hotzi`uha vetisaref.[33]

Judah’s repentance and reformation. Before Tamar’s penalty can be carried out, her clever trap closes on the unsuspecting Judah. He is forced not only to recognize his ownership of the tokens of signet, bracelets, and staff she presents,[34] but also to see himself as he really is. In repentant frankness Judah admits: “She hath been more righteous than I.”[35]

Happily, this turn of events becomes the turning point for Judah’s life — and helps us understand why in later chapters he is the only one of the brothers willing to sacrifice himself in order to save Benjamin.[36] Through the events of Genesis 38, Judah has learned “what it is to lose sons, and to want to desperately to protect his youngest.”[37] He has come to know “what it means to stake oneself for a principle.”[38]

Joseph Tests His Brothers (Genesis 42-44)

Why did Joseph test Judah and his other brothers? Joseph needed to know whether his brothers had overcome their selfishness, hatred, and envy. Judah’s trials and repentance had prepared him for this test.

There had been a famine in the land where Jacob’s family lived.[39] Knowing that grain was available in Egypt, Jacob sent ten of his sons there to buy provisions.[40] He prevented them, however, from taking Benjamin — whom he supposed to be the last remaining son of his beloved Rachel — with them. He worried “lest … mischief befall [Benjamin],”[41] as it had earlier befallen Joseph when he had been left in the care of his envious brothers. Though the brothers led their father to believe that Joseph had been slain by a wild animal,[42] they had actually sold him to Midianites who brought him to Egypt as a slave.[43]

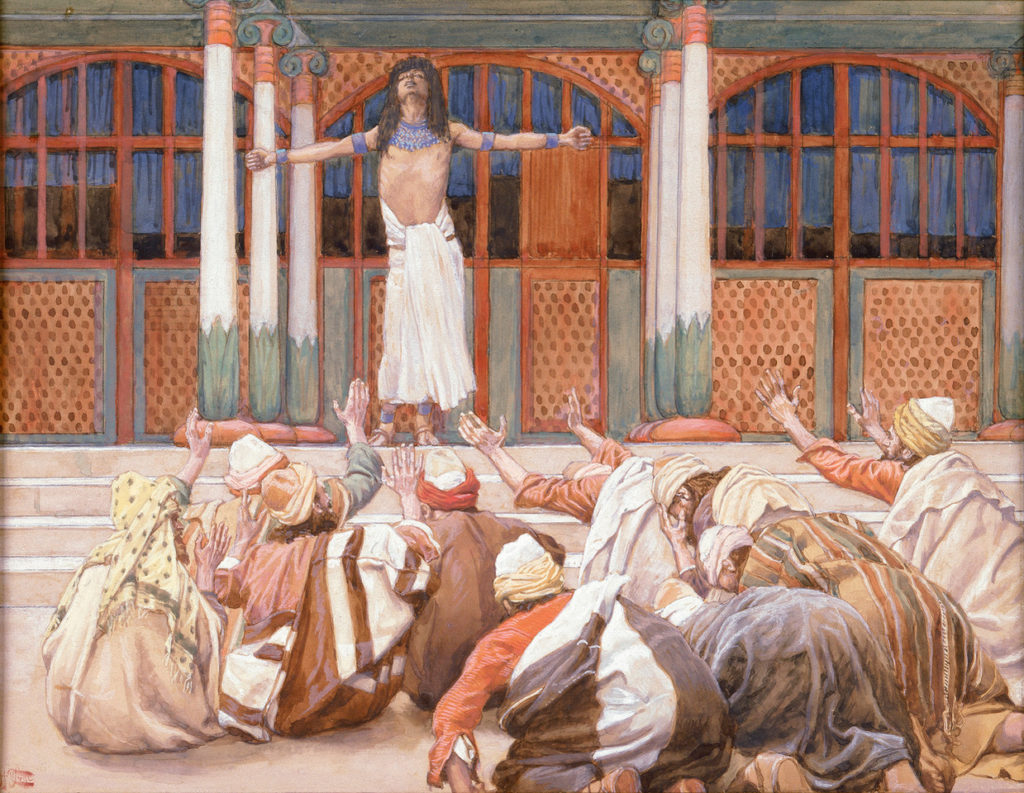

Figure 4. Jacques Joseph Tissot (1836-1902):

The Glory of Joseph

Although the brothers believed Joseph to be enslaved in obscurity or perhaps dead, Joseph had actually risen — through God’s design and his faithfulness — to a position of prominence in Egypt.[44] The brothers’ “last encounter with Joseph in Canaan, more than two decades earlier, was in an open field, where he was entirely in their power. Now, … they will be entirely in his power — whether for evil or for good they cannot say.”[45] This new situation, with Joseph as their indisputable superior, had been “predicted in his dreams.[46] He recognizes them but conceals his identity[47] and devises a deceptive scheme to test their loyalty to their youngest brother, Benjamin. This is the brothers’ punishment for their evil treatment of Joseph, but also provides an opportunity for redemption if they protect rather than abandon Benjamin.”[48]

The first phase of the test. At their initial meeting in Egypt, Joseph treated his brothers roughly and accused them of being spies.[49] Joseph put Simeon in prison and said he would not release him until they returned with their youngest brother.[50] All this Joseph did in the hope of provoking them to “godly sorrow”[51] and repentance for what they had done to him. The success of the first phase of the test is attested by the admission of Reuben:

We are verily guilty concerning our brother, in that we saw the anguish of his soul, when he besought us, and we would not hear; therefore is this distress come upon us.[52]

Joseph, deeply moved, “turned himself about from them, and wept.”[53]

Then, after binding Simeon “before their eyes”[54] so they could witness firsthand their brother’s mistreatment, Joseph sent the remaining brothers home. In order to further heighten their guilt and anxiety, Joseph instructed his servant to place the silver the brothers had used to pay for the grain in their packs.[55]

Some have questioned whether Joseph’s harsh tactics were justified. But Everett Fox explains: “Only by recreating something of the original situation — the brothers are again in control of the life and death of a son of [Rachel, i.e., Benjamin] — can [Joseph] be sure that they have changed. Once the brothers pass the test, life and covenant can then continue.”[56]

Robert Alter further observes: “The ‘test’ of bringing Benjamin to Egypt is actually a test of fraternal fidelity. Joseph may have some lingering suspicion as to whether the brothers have done away with Benjamin, the other son of Rachel, as they imagine they have gotten rid of him.”[57]

The second phase of the test. When Jacob and the brothers had returned home and saw the money in their sacks, they were greatly afraid,[58] thinking that the Egyptians might have done it as a deliberate means to accuse and entrap them when they returned.[59] The silver also served Joseph’s purposes as a deliberate reminder of the similar means by which they had once been paid for his sale as a slave.[60]

Figure 5. Jacques Joseph Tissot (1836-1902):

Jacob Mourns His Son Joseph

Jacob at first refused to send Benjamin back with them, seeing that he had already “lost” two sons (Joseph and Simeon), and fearing the worst for a third.[61] Trying to reassure his father, Reuben told Jacob that he would be willing to have his own two sons slain as a surety should Benjamin not return. The medieval Jewish rabbi David Kimhi captures the ridiculous nature of Reuben’s offer to kill his children in his paraphrase of Jacob’s reply: “‘Stupid firstborn! Are they your sons and not my sons?” This is not the only moment in the story when we sense that Reuben’s claim to preeminence among the brothers as firstborn is dubious.”[62] As the reader knows, “he will be displaced by Judah, the fourth-born.”[63]

In the end, the brothers know that they must return to Egypt again or face certain death because of the continuing famine.[64] This time it is Judah, in evident sincerity, who offered himself as a guarantee of Benjamin’s safe return: “I will be surety for him; of my hand shalt thou require him: if I bring him not unto thee, and set him before thee, then let me bear the blame for ever.”[65] Having no other choice, Jacob reluctantly relented, telling them to bring, in addition a double amount of silver for repayment allong with some luxury items as a gift to appease the Egyptians.[66] Ironically, the list of luxury items includes “a little balm, and a little honey, spices, and myrrh, nuts, and almonds,”[67] recalling the items in the Midianite caravan that carried Joseph into Egypt as a slave.[68]

Fearfully, the brothers were brought into Joseph’s own house, an ominous sign.[69] After seeing Benjamin, Joseph was so overcome he could utter no more than a few short words (“God be gracious unto thee, my son”[70]). Moved more deeply than before, he was constrained to leave the room quickly, “for his bowels did yearn upon his brother: and he sought where to weep; and he entered into his chamber, and wept there.”[71] Not wanting to disclose his emotions, “he washed his face, and [again] went out”[72] to his brothers.

According to Egyptian custom, Joseph sat apart while his brothers enjoyed the unexpected and bounteous hospitality of food and drink.[73] Pointedly, Joseph seated them from oldest to youngest — “a kind of dramatization of the contrast between knowledge and ignorance — ‘and he recognized them but they did not recognize him’ — that has been paramount from the moment the brothers first set foot in Egypt.”[74] “The youngest has the most lavish portion, recalling Joseph’s previous status within the family, which might kindle the jealousy of the older brothers. But the brothers drank and were merry, with no hint of resentment.”[75]

Figure 6. Jacques Joseph Tissot (1836-1902):

The Cup Found

The third and final phase of the test. As Joseph sent his brothers away with their grain, he again returned all their silver to their sacks. But in addition, as a final phase of the test, Joseph told his steward to “put my cup, the silver cup, in the sack’s mouth of the youngest.”[76] The idea is, of course, to justify Joseph in bringing charges of theft against Benjamin. “This is, of course, the last turn of the screw in Joseph’s testing of his brothers: will they allow Rachel’s other son to be enslaved, as they did with her elder son?”[77]

An important detail is revealed in Joseph’s charge to his steward, namely that Joseph uses the cup not only for drinking but also for “divining” — in other words, he employs it as a means to discern the real truth of hidden matters.[78] In this revelation, the careful reader will detect the irony in Joseph’s statement: while it is true that Joseph will acquire information by means of the cup, he will not do so by the usual superstitious means of pouring liquid into it and watching how it ripples. Rather he will use it in a different manner to “divine” his brothers’ repentance and reform.[79] The unexpected appearance of the silver cup in the sack of Benjamin will test their willingness to lay their own lives on the line to save the youngest. Once the results of the test are made clear to the brothers, they will have no doubt that “such a man as [Joseph] can certainly divine.”[80]

Figure 7. Arent de Gelder (1645-1727): Judah and Joseph, 1685

It will be remembered that Judah had made a solemn promise to Jacob, specifically offering himself as a surety for Benjamin.[81] Significantly, it is Judah’s impassioned speech — the longest speech in Genesis, which includes the renewal of promise to offer himself as a sacrifice in place of his brother — that saves the entire family, including those whom Jacob had presumed were already irretrievably gone.[82]

Judah ends his speech by recognizing the grief that will come upon his father with the loss of Benjamin: “How shall I go up to my father, and the lad be not with me? lest peradventure I see the evil that shall come on my father.”[83] “This of course,” comments Alter, “stands in stark contrast to his willingness years before to watch his father writhe in anguish over Joseph’s supposed death. The entire speech, as these concluding words suggest, is at once a moving piece of rhetoric and the expression of a profound inner change. Joseph’s ‘testing’ of his brothers is thus also a process that induces the recognition of guilt and leads to … transformation."[84]

Joseph and His Brothers Are Reconciled (Genesis 45)

Figure 8. Jacques Joseph Tissot (1836-1902):

Joseph Makes Himself Known to His Brethren

After hearing Judah’s moving speech, Joseph “could [no longer] refrain himself.”[85] Though he had all the Egyptians sent out so he could remain alone with his brothers, he wept in a voice so loud that all of them could still hear.[86]

When he was able to speak, he said, in “a two-word [Hebrew] bombshell tossed at his brothers”[87]: “I am Joseph.”[88] “He follow[ed] this by asking whether his father is alive, as though he could not altogether trust the assurances they had given him about this when he questioned them in his guise of Egyptian viceroy.”[89]

After telling his brothers to come close to him (they are “troubled”[90] by his words and still hold their distance), he identified himself again, saying: “I am Joseph your brother, whom ye sold into Egypt.”[91] “The qualifying clause Joseph now adds to his initial ‘I am Joseph’ is surely a heart-stopper for the brothers, and could be construed as the last — inadvertent? — gesture of his test of them. Their most dire imaginings of retribution could easily follow from these words, but instead, Joseph immediately proceeds in the next sentence to reassure them.”[92] He says, in the style of plain simplicity that true forgiveness teaches: “Now therefore be not grieved, nor angry with yourselves, that ye sold me hither: for God did send me before you to preserve life.”[93]

The tenderness of Joseph’s words recalls the sweet reconciliation of Shakespeare’s King Lear with his daughter Cordelia. Lear expects fierce recriminations from Cordelia as do the ten brothers from Joseph. Instead, in both stories, the one most wronged becomes the first to forgive. Every troubled feeling is suddenly transformed into joy at the simple, repeated expression of Cordelia’s unchanged love for her father:[94]

Lear: “I know, you do not love me, … You have some cause. …

Cordelia: No cause, no cause.[95]

In the account of Judah and Joseph, the “personal story is intertwined with the national one.”[96] Although a single nation of Israel eventually will reach a glorious zenith during the rule of David, the redactor of Genesis already knows that that united monarchy will soon fracture into rival northern and southern kingdoms led by the tribes of Joseph and Judah respectively. Thus, while the personal story of the reconciliation of Jacob’s immediate family is found by glancing backward in history, the happy ending to the corresponding national story still lies ahead. The day will yet come when Joseph’s seed will be “a light unto [Judah], … to bring salvation unto them when they are altogether bowed down under sin.”[97]

The Why

“The whole inset of Genesis 38… concludes with four verses devoted to Tamar’s giving birth to twin boys, her aspiration to become the mother of male offspring realized twofold. Confirming the pattern of the whole story and of the larger cycle of tales, the twin who is about to be second-born somehow ‘bursts forth’ (parotz) first in the end, and he is Peretz, progenitor of Jesse from whom comes the house of David.”[98] From the same line of Judah, who enacted a small similitude of the Son of God in his willingness to sacrifice himself in behalf of his brother, will come the Savior of the world, Jesus Christ.

A repeated lesson of scripture is that neither ancestry nor primogeniture is the final determinant of one’s blessings. As Gunther Plaut summarizes:[99]

Both [the story of Tamar and the story of Ruth] emphasize that King David [as well as his descendant Jesus Christ] stemmed from a strange and non-indigenous line: Tamar and Ruth were not Israelites, both were widows, and both claimed a son by dint of the levirate tradition. … After tragedy had marred their lives, it appeared that Tamar and Ruth would remain childless, but God in His wisdom turned fate to His own design. The Judah-Tamar interlude is, therefore, … an important link in the main theme: to show the steady, though not always readily visible, guiding hand of God who never forgets His people and their destiny.

Thanks to Kathleen M. Bradshaw and Stephen T. Whitlock for their careful proofreading and valuable suggestions.

Further Study

For a scripture roundtable video from The Interpreter Foundation on the subject of Gospel Doctrine lesson 11, see https://interpreterfoundation.org/scripture-roundtable-61-old-testament-gospel-doctrine-lesson-11-how-can-i-do-this-great-wickedness/.

For a related Book of Mormon Central KnoWhy, see https://knowhy.bookofmormoncentral.org/content/should-2-nephi-11-412-be-called-the-testament-of-lehi

References

Alter, Robert. The Art of Biblical Narrative. New York: Basic Books, 1981.

———, ed. The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary. New York City, NY: W. W. Norton, 2004.

Attridge, Harold W., Wayne A. Meeks, Jouette M. Bassler, Werner E. Lemke, Susan Niditch, and Eileen M. Schuller, eds. The HarperCollins Study Bible, Fully Revised and Updated Revised ed. New York City, NY: HarperOne, 2006.

Fox, Everett, ed. The Five Books of Moses: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy. The Schocken Bible: Volume I. New York, NY: Schocken Books, 1995.

Hendel, Ronald S. "Genesis." In The HarperCollins Study Bible, Fully Revised and Updated, edited by Harold W. Attridge, Wayne A. Meeks, Jouette M. Bassler, Werner E. Lemke, Susan Niditch and Eileen M. Schuller. Revised ed. New York City, NY: HarperOne, 2006.

King, Arthur Henry. 1971. "The Child is Father to the Man." In Arm the Children: Faith’s Response to a Violent World, edited by Daryl Hague, 101-19. Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 1998.

Plaut, W. Gunther, ed. The Torah: A Modern Commentary. New York City, NY: Union of American Hebrew Congregations, 1981.

Rendsburg, Gary A. 1986. The Redaction of Genesis. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2014.

Sandmel, Samuel, M. Jack Suggs, and Arnold J. Tkacik, eds. The New English Bible with the Apocrypha, Oxford Study Edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 1976.

Shakespeare, William. 1605. "The Tragedy of King Lear." In The Riverside Shakespeare, edited by G. Blakemore Evans, 1240-305. Boston, MA: Houghton-Mifflin Company, 1974.

Walton, John H. "Genesis." In Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, edited by John H. Walton. Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary 1, 2-159. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2009.

Endnotes

It hardly takes deep analysis into the Joseph Story to realize that [Genesis 38] is a unit with no direct relationship to the general story line. Joseph is nowhere mentioned, and although there are connections [with the stories that precede and follow it], the narrative is complete without 38:1–30. That this chapter is an interlude has not only been recognized by modern scholars, but by Rashi and Ibn Ezra centuries ago.

Ronald Hendel comments similarly (R. S. Hendel, Genesis (HarperCollins), Genesis 38:1-30):

Among the story’s remarkable features is the heroic prominence of a righteous foreign woman in contrast to the usually dangerous foreign woman, exemplified by Potiphar’s wife in ch. 39.

Rather, “leader.” Hebrew nazir may here be ‘one who wears the nezer,’ the symbol of royal power, as in 2 Samuel 1:10 and 2 Kings 11:12. Another tradition takes it in the sense of “separated,” a transferred use of its usual meaning. “Nazarite,” meaning the one who took vows of abstinence as detailed in Numbers 6:1-6. This refers to the early relationships between Joseph and his brothers. Since Hebrew nezer also means “the hair of the head” (Jeremiah 7:29) — the outward characteristic of the Nazarite, who is not permitted to cut his hair — a word play with ro’sh and kodkod is probably intended.

The custom of levirate marriage mandated that if a man died without a male heir, a relative was to sire a son with the widow on his behalf. A number of possible motives or anticipated results may underlie this custom, and the issue is still disputed. Alternative and not unrelated possibilities include provision of an heir, protection of the family holdings and/or dowry, or caring for the widow. Information from the ancient Near East comes from family documents from Emar as well as Hittite laws and Middle Assyrian laws.554

Westbrook points out that care for the widow cannot be seen as the sole motive, for then the legislation would simply mandate that the dead husband’s family care for her. He also points out that it is unlikely for the retention and benefit of the dowry to be the motivation, for then the new husband would have much to gain and would hardly view the task as unpleasant duty. The primary beneficiary of the practice must therefore be considered to be the dead husband rather than the surviving family. But as Westbrook concludes, it is not simply for the memory of the dead father that an heir must be born, but so that the deceased might be provided with an heir to his estate. If the land has been forfeited, the relative must redeem it for the widow and then produce an heir to whom to pass it.

It should be pointed out that the law pertains when brothers are living together (cf. Deuteronomy 25:5). Westbrook concludes that this refers to a situation in which the inheritance has not yet been divided. In such a case, if one brother dies, each of the others would receive a larger share. Three circumstances call for the invoking of the levirate rule:

father is alive and brothers are still living in his house

father is dead but the inheritance has not yet been divided

land has been alienated and levir must redeem it.

The punishment of burning is rare and reserved for the most serious of sexual crimes (cf. Lev. 20:14; 21:9 for the only other biblical occurrences). … This was a most serious punishment since it probably precluded proper burial.

The same verb, moreover, will play a crucial thematic role in the dénouement of the Joseph story when he confronts his brothers in Egypt, he recognizing them, they failing to recognize him. … The first use of the [recognition] formula was for an act of deception; the second use is for an act of unmasking. Judah with Tamar after Judah with his brothers is an exemplary narrative instance of the deceiver deceived. … In the most artful of contrivances, the narrator shows him exposed through the symbols of his legal self given in pledge for a kid (gedi `izim), as before Jacob had been tricked by the garment emblematic of his love for Joseph which had been dipped in the blood of a goat (se`ir `izim).

The idea that a cup was used for divination suggests that divination took place by observing liquids poured into the cup (either the shapes of oil on water or the ripples of the water, to name a few techniques known from Mesopotamia). Little is known of these techniques in Egyptian practice. Divination was a means of acquiring information. It is of interest that Joseph acquires information by means of the cup — not by pouring liquid into it, but by using it to test his brothers, thus using observation at a different level.

Excellent!

Of course there is much more to the intertwining of the descendants of Joseph and Judah which was beyond the scope of your article. I will mention just a few thoughts.

Of all the Israelites that came out of Egypt the only two that entered into the Promised Land were Joshua, the leader of tribe of Ephraim (Joseph), and Caleb, the leader of the tribe of Judah. There has to be some significance in that.

Concerning the latter-days we read:

“The envy also of Ephraim shall depart, and the adversaries of Judah shall be cut off: Ephraim shall not envy Judah, and Judah shall not vex Ephraim. But they shall fly upon the shoulders of the Philistines toward the west; they shall spoil them of the east together: they shall lay their hand upon Edom and Moab; and the children of Ammon shall obey them.” (Isaiah 11:13-14)

The stage is set for this occur any day now.

Abraham and his seed were given the responsibility to teach the Gospel to all the world for the rest of time (Abraham 2:9). This responsibility was transferred to Jacob and his descendants. When Jacob gave Judah his patriarchal blessing he said:

Judah is a lion’s whelp: from the prey, my son, thou art gone up: he stooped down, he couched as a lion, and as an old lion; who shall rouse him up? (Genesis 49:9).

In this symbolic blessing God is the lion and Judah is His son. The prey is the food of God, that is, the Gospel, the bread of life. Judah went away from the fullness of the Gospel, lay down on the job and rejected the responsibility of teaching it to the world. In the latter days, who shall rouse him up? The answer is obvious. Joseph must rouse up Judah.

“…seek diligently to turn the hearts of the children to their fathers, and the hearts of the fathers to the children; And again, the hearts of the Jews unto the prophets, and the prophets unto the Jews; lest I come and smite the whole earth with a curse, and all flesh be consumed before me.” (D&C 98:16-17

It appears that the Millennium of Peace cannot be brought to pass unless Joseph rouses Judah to a full knowledge and sense of his responsibility.

Thank you, Theodore. In fact, next week the blessings of Judah and Joseph (Genesis 49) will be the subject of the article.

Thank you for your comments, Theodore. In fact, next week the blessings of Judah and Joseph (Genesis 49) will be the subject of the article.

Really liked this one.

Why the ‘Lysoling’ on Tamar’s story?

Greg–

There are so many additional things that could have been said, but I had to discipline myself a bit knowing that the details of Genesis 38 were really not central to the question that motivated this article: namely why Joseph and Judah’s story were intertwined. You will see that in order to keep my focus on the question at hand, I take the same tactic in other articles. For example, in the last article I felt I needed to skip over many interesting details of the story of Jacob and Laban and the sheep/goats.

People already complain that my articles are too long, so you can only imagine how miserable I would make readers if I tried to turn them into verse-by-verse commentaries! 🙂

Thanks for your comment, Kent. From my own professional training and experience in clinical psychology, I wholeheartedly concur with your recommendation of your book an excellent resource for those who are dealing with this difficult problem. I also agree that it may take time and great effort to forgive others to achieve reconciliation and peace.

That said, my own study of the story of Joseph leads me to conclude that it is a misreading of Genesis to describe the account from the perspective of modern psychology. This interpretation simply cannot be sustained or justified through an appeal to scripture, but must be “read in” to the text from the outside using modern categories and framing of events that are not supported by the text of Genesis itself unless it is read at such a high level of abstraction as to obscure the important textual details that reveal the intent of the ancient redactors of Genesis.

Of course, none of this is meant to deny that Joseph was severely mistreated. Nor is it to deny his own personal growth and development throughout the Genesis account. But we cannot rely on general resemblances of events to modern situations of abuse as a reliable guide to scripture interpretation. Scripture must be read and understood on its own terms.

In short, though the psychological and emotional trauma of abuse is real the its consequences are serious, I find nothing compelling in the story itself, when it is read carefully in its ancient context, that commends its interpretation as a tale of survivor retribution. Though the story may seem strange and disturbing to us as it stands from a modern perspective, ancient scripture readers would have understood the genre, message, and cultural connotations as a story of divinely directed providence and testing.

The author may be interested in an alternate explanation for Joseph’s rough treatment of his brothers. This is due to Wendy Ulrich, in a chapter on forgiveness in the book Confronting Abuse, edited by Anne L. Horton, Barry Johnson, and myself. Wendy sees the situation as reflecting Joseph’s difficulty in forgiving his brothers, and draws the lesson that it may take time and great effort to forgive others (which point is not often made in church talks on forgiveness.