This series is cross-posted with the permission of Book of Mormon Central

from their website at Pearl of Great Price Central

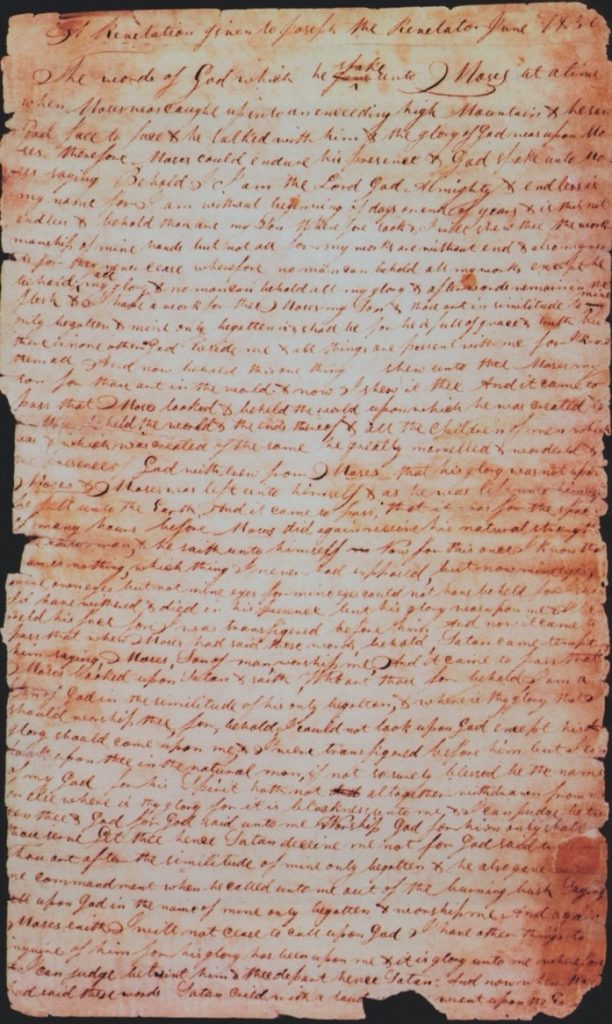

Figure 1. Old Testament Manuscript 1, Page 1, 1830. A revelation given to Joseph the Revelator, June 1830. This page, in Oliver Cowdery’s handwriting, records the text of Moses 1:1–19

This collection of frequently asked questions (FAQ) addresses general topics relating to the Book of Moses:[1]

How Did We Get the Book of Moses?

The Book of Moses is an extract from the Joseph Smith Translation (JST) of the Bible, specifically from his translation of the book of Genesis. Joseph’s efforts to provide a translation of the Bible were in response to a divine command, and he explicitly called it a “branch of my calling.”[2]

In October 1829, Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery purchased a Bible that was eventually used in the preparation of the JST.[3] However, in light of the press of events surrounding the publication of the Book of Mormon and the subsequent organization of the Church on April 6, 1830, the first revelation related to Bible translation, Moses 1, was not received until June 1830. Moses 1 can be best understood as a prologue to Genesis.[4]

In August 1832, the first published extract from JST Genesis, Moses 7, appeared in the Church’s newspaper, The Evening and Morning Star.[5] Publication continued with additional extracts from the new translation (Moses 6:43–68, 5:1–16, and 8:13–30) in March and April 1833.[6] Two years later, several verses from Moses 2–5 were used in the publication of the Lectures on Faith in the 1835 Doctrine and Covenants.[7] Finally, Moses 1 appeared in the January 16, 1843 issue of the Times and Seasons.[8]

The manuscript and publication history of the Book of Moses is complex and often misunderstood. Mostly drawing on the earlier newspaper publications, Elder Franklin D. Richards published portions of Moses 1–8 in the first edition of the Pearl of Great Price, printed in England in 1851. However, later editions of the Pearl of Great Price instead relied primarily on the version of Moses 1–8 that had been published by the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (RLDS, now renamed the Community of Christ). Importantly, besides containing changes made by later editors, versions of the Pearl of Great Price up to the present time omit many revisions to the original dictation in the Old Testament 1 (OT1) manuscript that were made subsequently in the Old Testament 2 (OT2) manuscript of the Book of Moses.[9]

The Prophet’s wife, Emma, had kept the original JST manuscripts until 1866, when they were given to the RLDS Church. Based on a review of the original manuscripts by an RLDS publication committee, the “Inspired Version” (I.V.) of the Bible first appeared in 1867. In 1944, the RLDS Church brought out a carefully prepared “new corrected edition.” However, because Latter-day Saint scholars had not yet had an opportunity to compare the I.V. to the original manuscripts, its initial acceptance by Church members was limited.[10]

A thorough study by Brigham Young University (BYU) religion professor Robert J. Matthews was published in 1975.[11] He established that the 1944 and subsequent editions of the “Inspired Version,” notwithstanding their shortcomings, constituted a faithful rendering of the work of the Prophet Joseph Smith and his scribes—insofar as the manuscripts were then understood.[12]

In 1979 and 1981, the Church first published new editions of the scriptures which contained, along with various study aids, extracts of many (but not all) revisions from the JST.[13] Elder Boyd K. Packer heralded this publication event as “the most important thing that [the Church has] done in recent generations.”[14] Although it is not the official Bible of the Church, the JST is seen as an invaluable aid in scripture study and a witness for the calling of the Prophet Joseph Smith.[15] In particular, the JST texts of Genesis 1–8 (Book of Moses) and Matthew 24 (Joseph Smith—Matthew) hold a place of special importance in the Latter-day Saint scriptural canon since they have been wholly incorporated within the Pearl of Great Price.

With painstaking effort over a period of eight years, and with the generous cooperation of the Community of Christ, a facsimile transcription of all the original manuscripts of the JST was at last published in 2004.[16] A detailed study of the text of the portions of the JST relating to the Book of Moses appeared in 2005.[17] Taken together, these studies allow us to see the process and results of translation with greater clarity than ever before.

Oliver Cowdery and Joseph Smith … did not state their purpose in purchasing the Bible at that time, but in view of the instructions and experiences they had received, it is possible that they were thinking of a new translation of the Bible even at that early date.

Moses 1 was recorded on the first three pages of a fifty-two page folio that continued without a break into the translation of the first chapters of Genesis, and was similarly positioned in later JST manuscripts. It seems reasonable to conclude that Moses 1 was not merely “an independent revelation that evolved into a retranslation of the Bible” (R. L. Bushman, Mormonism, p. 64), but rather was preconceived as an integral part of the translation project from its inception.

What Kinds of Challenges Was Joseph Smith Facing at the Time He Received Moses 1?

The account of Moses’ vision was no doubt reassuring to Joseph Smith as he faced his own trials during the period this revelation was received. Richard L. Bushman observes that Moses’ test “echoed Joseph’s struggle with darkness before his First Vision.[18] … The Book of Moses … conveys the sense of prophethood as an ordeal. Visions of light and truth alternate with evil and darkness.”[19]

Moses 1 was given to Joseph Smith at such a time of alternation of darkness and light. Although he and Oliver Cowdery had purchased a large pulpit-style edition of the King James Bible in Palmyra in October 1829,[20] it was not until June 1830—during a period of jubilant expectation and intense persecution—that he was able to free himself to begin a new work of translation that was intended to restore “many important points touching the salvation of men, [that] had been taken from the Bible, or lost before it was compiled.”[21] Many wonderful events had recently transpired: the Book of Mormon had come from the press in March, the Church had been organized in April, and the first conference had been held in early June. On the other hand, tremendous opposition began to mount during a visit of the Prophet to the Saints in Colesville, New York later that month. As Bushman described it:[22]

On Saturday afternoon, June 26, they dammed a small stream to make a pond for baptisms and appointed a meeting for the Sabbath. That night the dam was torn out. The Mormons replaced the dam early Monday morning and held their baptism later that day… On their way back, a collection of the Knight’s neighbors scoffed at the new Mormons as they passed by. Later about fifty men surrounded Joseph Knight’s house, Joseph Smith said, “raging with anger, and apparently determined to commit violence upon us.” When Joseph left…, the mob followed along, threatening physical attack. …

When village toughs failed to stop the baptisms, the law stepped in. Before the newly baptized members could be confirmed, a constable from South Bainbridge delivered a warrant for Joseph’s arrest. … On June 28, he was carried off to court in South Bainbridge by constable Ebenezer Hatch, trailed by a mob that Hatch thought planned to waylay them en route. When a wheel came off the constable’s wagon, the mob nearly caught up, but, working fast, the two men replaced it in time and drove on. Hatch lodged Joseph in a tavern in South Bainbridge and slept all night with his feet against the door and a musket by his side. …

The hearing [the next day] dragged on until night, when Justice Chamberlain… acquitted Joseph. Joseph had no sooner heard the verdict than a constable from neighboring Broome County served a warrant for the same crimes. The constable hurried Joseph off on a fifteen-mile journey without a pause for a meal. When they stopped for the night, the constable offered no protection from the tavern-haunters’ ridicule. After a dinner of crusts and water, Joseph was put next to the wall, and the constable lay close against him to prevent escape.

At ten the next morning, Joseph was in court again… [Joseph’s lawyer John Reed] said witnesses were examined until 2 a.m., and the case argued for another two hours. The three justices again acquitted Joseph. … The next day Joseph and Emma were safely home in Harmony.

Joseph and Cowdery tried to steal back to Colesville a few days later to complete the confirmations that the trials had interrupted, but their enemies were too alert. They had no sooner arrived at the Knights’ than the mob began to gather. The Knights had suffered along with Joseph. On the night of the South Bainbridge trial, their wagons had been turned over and sunk in the water. Mobbers piled rails against the doors and sank chains in the stream. On Joseph’s and Cowdery’s return to Colesville, there was no time for a meeting or even a meal before they had to flee. Joseph said they traveled all night, “except a short time, during which we were forced to rest ourselves[s] under a large tree by the way side, sleeping and watching alternately.”

A later account coolly summarized the trying circumstances during the month of June 1830 and described how the revelation of Moses 1 had provided needed encouragement:[23]

I will say, however, that amid all the trials and tribulations we had to wade through, the Lord, who well knew our infantile and delicate situation, vouchsafed for us a supply of strength, and granted us “line upon line” of knowledge—“here a little and there a little,”[24] of which the [vision of Moses] was a precious morsel.

How Was the Book of Moses Translated?

Book of Moses scholar Kent P. Jackson summarized the translation process that began with Moses 2 (i.e., Genesis 1) as follows:[25]

Beginning with Genesis 1:1, the Prophet apparently had the Bible before him and read aloud from it until he felt impressed to dictate a change in the wording. If no changes were required, he read the text as it stood. Thus dictating the text to his scribes, he progressed to Genesis 24, at which point he set aside the Old Testament as he was instructed in a revelation on March 7, 1831.[26] The following day he began revising the New Testament. When he completed John 5 in February 1832, he ceased dictating the text in full to his scribes and began using an abbreviated notation system. From that time on it appears that he read the verses from the Bible, marked in it the words or passages that needed to be corrected, and dictated only the changes to his scribes, who recorded them on the manuscript. Following the completion of the New Testament in February 1833, Joseph Smith returned to his work on the Old Testament.

Without knowing more than this, one might reasonably assume that each chapter of the Bible received about the same amount of attention from the Prophet. However, by looking at the known durations of periods when each part of the translation was completed, we can discover that the first 24 chapters of Genesis occupied nearly a quarter of the total time Joseph Smith spent on the entire Bible translation. As a proportion of page count, changes in Genesis occur four times more frequently than in the New Testament, and twenty-one times more frequently than in the rest of the Old Testament. The changes in Genesis are not only more numerous, but also more significant in the degree of doctrinal and historical expansion. Though we cannot know how much of Joseph Smith’s daily schedule the translation occupied during each of its phases, it seems evident that Genesis 1–24, the first 1% of the Bible, must have received a significantly more generous share of the Prophet’s time and attention than did the remaining 99%.[27]

What important things could Joseph Smith have learned from translating Genesis 1–24? To begin with, the story of Enoch and his righteous city would have had pressing relevance to the mission of the Church, as the Prophet worked to help the Saints understand the law of consecration and to establish Zion in Missouri. Thus, it is understandable that this account was the first extract of the JST to be published in 1832 and 1833. However, we should not allow the salience of these immediate events to overshadow the importance of the fact that the first JST Genesis chapters also relate the stories of other prophets and patriarchs, especially Adam, Noah, Melchizedek, and Abraham. In consideration of this fact, and other evidence from revelations and teachings of this period, it has been suggested that the most significant impact of the translation process may have been the early tutoring in temple-related doctrines received by Joseph Smith as he revised and expanded Genesis 1–24, in conjunction with his later translation of relevant passages in the New Testament and, for example, Old Testament references to prophets such as Moses and Elijah.[28]

As to the results of the translation process, most scholars agree that the Prophet’s Bible translation in general, and the Book of Moses in particular, is not a homogeneous production. Rather, it is composite in structure and eclectic in its manner of translation. For example, the vision of Moses (Moses 1) and the story of Enoch (Moses 6–7) contain long, revealed sections that, although using King James Bible language, have little or no direct relationship to the Genesis narrative. However, other chapters are more in the line of clarifying commentary that takes the text of the King James Bible as its starting point, incorporating new elements based on Joseph Smith’s prophetic inspiration and understanding.[29] According to Philip Barlow, the most common type of change consists of “grammatical improvements, technical clarifications, and modernization of terms.”[30]

Of course, even in the case of passages that seem to be explicitly revelatory, it remained to the Prophet to exercise considerable personal effort in rendering these experiences into words.[31] As Kathleen Flake puts it, Joseph Smith did not see himself as “God’s stenographer. Rather, he was an interpreting reader, and God the confirming authority.”[32] Evidence from a study by Kent Jackson and Peter Jasinski of two New Testament passages that were translated twice indicates that in this particular instance the JST “is not being revealed word-for-word, but largely depends upon Joseph Smith’s varying responses to the same difficulties in the text.”[33]

With specific reference to large biblical additions of the Book of Moses, the original dictation in Old Testament Manuscript 1 is closer to a word-for-word revealed text than to anything else. In this general respect, the result of the effort is “much like the Book of Mormon.”[34] If we are not mistaken, some analogies to the Book of Mormon translation process may be in order. For example, in Royal Skousen’s careful examination of difficult readings and conjectural emendations made by scribes and editors (and doubtless sometimes by Joseph Smith himself) in the source manuscripts of the Book of Mormon, Skousen has “determined that a fair number were unlikely or unnecessary.”[35] Besides specific arguments related to the Prophet’s revelations and translations, the general literature is full of examples of scribes who made manuscripts worse through their unintentional or intentional “corrections.”[36]

Some aspects of the Book of Moses, possibly including the comprehensive understanding of the Creation and the Fall that both Moses and Joseph Smith received, may have first come in vision and only later have been put into words. Regarding such visionary experiences, Lorenzo Brown remembered Joseph Smith as saying:[37]

After I got through translating the Book of Mormon, I took up the Bible to read with the Urim and Thummim. I read the first chapter of Genesis, and I saw the things as they were done, I turned over the next and the next, and the whole passed before me like a grand panorama; and so on chapter after chapter until I read the whole of it. I saw it all!

However, even if Brown’s account is accurate, it is not likely that Joseph Smith recorded in a direct fashion everything that he saw and understood relating to the material in the Book of Moses. In the chapters where the book of Moses closely parallels the Genesis account (i.e., Moses 2–5, 8 vs. Moses 1, 6, 7), he seems to have emended the biblical text only to the degree he felt necessary and authorized to do so, running roughshod, as it were, over the divisions of biblical source texts generally accepted by scholars. For example, rather than compose a completely new account of Creation and the Fall in the Book of Moses, Joseph Smith wove in changes based on his prophetic insights piece-by-piece into the existing Genesis account.[38] As a result, in his effort to fulfill his divine mandate to “translate” scripture, the Prophet gives us enough revised and expanded material in the Book of Moses to significantly impact our understanding of important doctrinal and historical topics, but does not rework existing verses to the point they become unrecognizable to those familiar with the King James Bible.[39]

In redoing the early chapters of Genesis, the stories of Creation, of Adam and Eve, and the Fall were modified, but with less extensive interpolations than in the revelation to Moses. Joseph wove Christian doctrine into the text without altering the basic story. But with the appearance of Enoch in the seventh generation from Adam, the text expanded far beyond the biblical version. In Genesis, Enoch is summed up in 5 verses; in Joseph Smith’s revision, Enoch’s story extends to 110 verses.

Royal Skousen differs in his understanding of the translation process, arguing that the words chosen for the English text of the Book of Mormon were generally given under “tight control” (R. Skousen, Tight Control).

Did Joseph Smith Use Bible Commentaries in His Translation of the Book of Moses?

Research by Thomas Wayment and Haley Wilson Lemmon[40] suggests that Joseph Smith possessed a copy of Adam Clarke’s 1825 Bible commentary.[41] Research on the possibility that the Prophet used this commentary and perhaps other translation aids is ongoing. However, as things stand at the moment, Wayment has drawn attention to the fact that “there are no parallels to Clarke between Genesis 1–Genesis 24,”[42] where the Book of Moses corresponds to the first chapters of the JST Genesis account.

Is the Book of Moses in “Final” Form?

It would be a mistake to assume that the Book of Moses is currently in any sort of “final” form—if indeed such perfection in expression could ever be attained within the confines of what Joseph Smith called our “little, narrow prison, almost as it were, total darkness of paper, pen and ink; and a crooked, broken, scattered and imperfect language.”[43] As Robert J. Matthews, a pioneer of modern scholarship on the Joseph Smith Translation, aptly put it, “any part of the translation might have been further touched upon and improved by additional revelation and emendation by the Prophet.”[44]

Though Joseph Smith was careful in his efforts to render a faithful translation of the Bible, he was no naïve advocate of the inerrancy or finality of scriptural language.[45] For instance, although in some cases his Bible translation attempted to resolve blatant inconsistencies among different accounts of the Creation and the life of Christ, he did not attempt to merge these sometimes divergent perspectives on the same events into a single harmonized version. Of course, having multiple accounts of these important stories should not always be seen as a defect or inconvenience. Differences in perspective between such accounts—and even seeming inconsistencies—composed “in [our] weakness, after the manner of [our] language, that [we] might come to understanding,”[46] can be an aid rather than a hindrance to human comprehension, sometimes serving disparate sets of readers or diverse purposes to some advantage.

In translating the Bible, Joseph Smith’s criterion for the acceptability of a given reading was typically pragmatic rather than absolute. For example, after quoting a verse from Malachi in a letter to the Saints, he admitted that he “might have rendered a plainer translation.” However, he said that his wording of the verse was satisfactory in this case because the words were “sufficiently plain to suit [the] purpose as it stands.”[47] This pragmatic approach is also evident both in the scriptural passages cited to him by heavenly messengers and in his sermons and translations. In these instances, he often varied the wording of Bible verses to suit the occasion.[48]

There is another reason we should not think of the Book of Moses as being in its “final” form. Careful study of the translations, teachings, and revelations of Joseph Smith suggest that he sometimes knew much more about certain sacred matters than he taught publicly. Indeed, in some cases, we know that the Prophet deliberately delayed the publication of early temple-related revelations connected with his work on the JST until several years after he initially received them.[49] Even after Joseph Smith was well along in the translation process, he seems to have believed that God did not intend for him to publish the JST in his lifetime. For example, writing to W. W. Phelps in 1832, he said: “I would inform you that [the Bible translation] will not go from under my hand during my natural life for correction, revisal, or printing and the will of [the] Lord be done.”[50]

Although in later years Joseph Smith reversed his position and apparently made serious efforts to prepare the manuscript of the JST for publication, his own statement makes clear that initially he did not feel authorized to share publicly all he had produced—and learned—during the translation process. Indeed, a prohibition against indiscriminate sharing of some revelations, which parallels similar cautions found in pseudepigrapha,[51] is explicit in the Book of Moses when it says of one sacred portion of the account: “Show [these words] not unto any except them that believe.”[52] Such admonitions are consistent with a remembrance of a statement by Joseph Smith that he intended to go back and rework some portions of the Bible translation to add in truths he was previously “restrained … from giving in plainness and fulness.”[53]

Does the Book of Moses Restore the Original Text of Genesis?

In an 1834 letter from Joseph Smith and other elders in Kirtland to the Saints, we read: “[f]rom what we can draw from the Scriptures relative to the teaching of heaven, we are induced to think that much instruction has been given to man since the beginning which we have not.”[54]

Kathleen Flake summarized how scholarly views of the Bible have moved in the direction of Joseph Smith’s views since he made the statement above:[55]

Today, the Bible itself is believed to be largely the product of periodic manipulation of foundational texts. “Redaction” has become the preferred term for an invasive revision of a source that seamlessly inserts new material in an authoritative text in order to meet new exigencies. Though only a gleam in the eye of the academy at the time Smith was writing and still a source of concern for literalist readers, redaction has become the regnant explanation for the construction of the Bible as having “experienced change, accretions, and reinterpretations as it was being transmitted through centuries.”

Speaking specifically of the Book of Moses, Latter-day Saint teachings and scripture clearly imply that Moses learned of the Creation and the Fall in vision and was told to write it. Moreover, there are revelatory passages in the Book of Moses that have remarkable congruencies with ancient texts. However, it is probably fruitless to rely on JST Genesis as a means for uncovering a Moses urtext. Even if, for example, the longer, revelatory passages of chapters 1, 6, and 7 of the Book of Moses were found to be direct translations of ancient documents, it is impossible to establish whether or not they once existed in that form as an actual part of some sort of “original” manuscript of Genesis or whether they were instead “lost before it was compiled.”[56]

Latter-day Saints understand that the primary intent of modern revelation is for divine guidance to latter-day readers, and not necessarily to provide precise matches to texts from other times. Because this is so, we would expect, rather, to find deliberate deviations from the content and wording of ancient manuscripts in Joseph Smith’s translations in the interest of clarity and relevance to modern readers.[57] As Elder Hyrum M. Smith, a former apostle, expressed it, “the Holy Spirit does not quote the Scriptures, but gives Scripture.”[58] If we keep this perspective in mind, we will be less surprised with the appearance of New Testament terms such as “Jesus Christ” in the Book of Moses account of Enoch when the title “the Son of Man” would be more in line with ancient Enoch texts.[59]

In most instances, the new materials [in the JST] uses archaic pronouns and verbal conjugations, clearly patterned after the language of the King James translation. But the language does not give the impression of formality and antiquity as much as does the KJV. Both in vocabulary and in syntax, the wording is more contemporary, and thus the meaning is more clear.

The Holy Spirit may inspire scripture, and that scripture may take a particular form at a particular time, undergo redactions, and then the Holy Spirit may indeed quote either the original or a revised version of the scripture (which is a combination of spiritual influence and human exigency) while simultaneously inspiring the current recipient of the revelation to understand the core essence or truth that stood behind the scripture to begin with.

This point reminds us that we must never lose sight of the most rigorous requirement of all in scripture interpretation: namely, that we cannot “receive the word of truth” except “by the Spirit of truth” (D&C 50:19). “To put it bluntly,” wrote Hugh Nibley, “short of revelation, no real translation of [scripture — or, for that matter, any inspired interpretation or teaching —] is possible” (H. W. Nibley, H. W. Nibley, Message (2005), p. 55). Indeed, for their own witness of any religious truths, including the revelations of others, Latter-day Saints look to personal revelation. Speaking of this pattern, David Holland wrote: “Personal confirmation replaced the canon walls as the barrier to deception and tyranny. Revelation checked revelation” (D. F. Holland, Sacred Borders, p. 153. Holland draws on pertinent teachings of Brigham Young in this regard).

Notably, Ben McGuire observes that sometimes, rather than leading us to interpret scripture by learning “all we can about the context in which it was written,” the Spirit may direct us instead to “reinterpret it radically for a new context” (B. L. McGuire, 15 August 2017).

Joseph Smith set an example of flexibility in this regard. He taught not only that scripture should be interpreted by “enquiring” about the particulars of the situation that “drew out the answer” (J. Smith, Jr., Teachings, 29 January 1843, p. 276. Cf. J. Smith, Jr. et al., Words, Willard Richards, 29 January 1843, p. 161; J. Smith, Jr. et al., Journals, 1841-1843, 29 January 1843, p. 252) for a given teaching in its ancient context, but also, like Nephi, radically reshaped some of his interpretations in order to “liken them” (1 Nephi 19:24. Cf. 1 Nephi 19:23; 2 Nephi 11:2, 8) to the situation of those living in the latter days. Indeed, on many occasions, the specifics of Joseph Smith’s interpretations of scripture and doctrinal pronouncements can be understood only with reference to current events.

Did Moses Write the Book of Genesis?

An impressive array of evidences for the seeming diversity of sources within the first five books of the Bible have converged to form the basis of the Documentary Hypothesis, a broad scholarly consensus whose most able current popular expositor has been Richard Friedman.[60] However, even those who find the Documentary Hypothesis—or some variant of it—compelling have good reason to admire the resulting literary product on its own terms. For example, in the case of the two Creation chapters, Friedman himself writes that in the scriptural version of Genesis we have a text “that is greater than the sum of its parts.”[61] John Sailhamer aptly summarized the situation when he wrote that “Genesis is characterized by both an easily discernible unity and a noticeable lack of uniformity.”[62]

The idea that a series of individuals may have had a hand in the authorship and redaction of Genesis should not be foreign to readers of the Book of Mormon, where inspired editors have explicitly revealed the process by which they wove separate overlapping records into the finished scriptural narrative. The authors and editors of the Book of Mormon knew that their account was preserved not only for the people of their own times, but also for future generations,[63] including our own.[64]

Of course, in contrast to the carefully controlled prophetic redaction of the Book of Mormon, we do not know how much of the writing and editing of the Old Testament may have taken place with less inspiration and authority.[65] And although the processes of selection, transmission, and translation of ancient scripture were doubtless guided in at least some respects by the divine Hand,[66] these long and complex processes were not wholly accomplished under prophetic supervision. Joseph Smith said: “I believe the Bible … as it came from the pen of the original writers.”[67]

Scholarly conversation on the Documentary Hypothesis and other important issues in higher criticism is, of course, ongoing. Although broad agreement persists on many issues, the state of research on the composition of the Pentateuch continues to evolve in important ways. In 2012, Konrad Schmid gave the following assessment:[68]

Pentateuchal scholarship has changed dramatically in the last three decades, at least when seen in a global perspective. The confidence of earlier assumptions about the formation of the Pentateuch no longer exists, a situation that might be lamented but that also opens up new and—at least in the view of some scholars—potentially more adequate paths to understand its composition. One of the main results of the new situation is that neither traditional nor newer theories can be taken as the accepted starting point of analysis; rather, they are, at most, possible ends.

However, despite these and other unresolved complexities, there is little doubt that the basic principles of source criticism behind the Documentary Hypothesis are here to stay.

The idea that scriptural figures may sometimes be more accurately regarded as the authorities rather than the direct authors or scribes for biblical books associated with their names is not necessarily inconsistent with Latter-day Saint acceptance of the Bible as scripture “as far as it is translated [and transmitted] correctly.”[69] Though we should have no quarrel with the idea that the Old Testament, as we have it today, might have been compiled at a relatively late date from many sources of varying perspectives and levels of inspiration, we are able to accept that its major figures were historical and that the sources may go back to authentic traditions (whether oral or written), associated with these figures as authorities.[70]

These views about the authorship of the Old Testament are consistent with the increasing recognition of the importance of the role of oral transmission in the preservation of religious traditions that were later normalized by scribes—both with respect to the Bible[71] and the Book of Mormon.[72] It should also be noted that vestiges of otherwise lost oral or written traditions[73] are sometimes included in extracanonical texts.[74] Significantly, such writings rarely if ever constitute de novo accounts. Rather, they tend to incorporate diverse traditions of varying value and antiquity in ways that make difficult the teasing out of the contribution that each makes to the whole.[75] As a result, even relatively late documents rife with midrashic speculations unattested elsewhere,[76] unique Islamic assertions,[77] or seemingly fantastic Christian interpolations[78] may sometimes preserve fragments of authentically inspired principles, history, or doctrine, or may otherwise bear witness of legitimate exegetically derived[79] or ritually transmitted[80] realities. While the inspiration, legitimacy, or reality of these teachings may be debated by scholars, Latter-day Saints have a distinct advantage in testing their worth and antiquity through close comparison with Latter-day Saint teachings and scripture and the companionship of the Holy Spirit.[81]

In trying to imagine more concretely how authority and authorship may have come together in the writing of prophetic teachings and revelations that may have originated, in part, in oral sources, we have modern day analogues. Consider, for example, the fact that Joseph Smith’s Nauvoo sermons were neither written out in advance nor taken down by listeners verbatim as they were delivered. Rather, they were copied as notes and reconstructions of his prose (sometimes retrospectively) by a small number of individuals, generally including an official scribe.[82] These notes were in turn shared and copied by others.[83] Later, as part of serialized versions of history that appeared in church publications, many (but not all) of the notes from such sermons were expanded, amalgamated, and harmonized; prose was smoothed out; and punctuation and grammar were standardized. Sometimes the wording of related journal entries from scribes and others was changed to the first person and incorporated into the Documentary History of the Church[84] in order to fill in gaps, an accepted practice at the time.[85]

Over the years, various compilations drew directly from these published accounts[86] while, more recently, transcriptions of contemporary notes (including sources that were unavailable to historians who produced the standard amalgamated versions) were also collected and published.[87] Translations of these accounts into different languages sometimes created new difficulties.[88]

The important point in all this is that while each of these published accounts of the Prophet’s Nauvoo sermons has been widely used to convey his teachings to church members on his authority, it is likely that none of these accounts was written or reviewed by him personally.[89] Moreover, less than two hundred years after these sermons were delivered, multiple variants in their content and wording—none of which completely reflect the actual words spoken—are in common circulation. In some cases, imperfect transcriptions of Joseph Smith’s words led to misunderstandings of doctrine by early Church leaders and, in consequence, have been explicitly corrected by later Church leaders. One need look no further than the March 2014 edition of the Ensign for an apostolic correction of this sort.[90]

What this example is intended to show is how easily divergence in written records can happen, even in the best case where like-minded “scribes,” recording events as they occurred, are doing the best they can to preserve the original words of a prophet. This phenomenon also helps explain the great lengths that Joseph Smith went to in order to preserve an accurate written record of the doings of his day.

Returning to our original question, though we find it doubtful that Moses wrote every word ascribed to him in the Bible as we now have it, Latter-day Saints accept him as the authority behind important biblical works, and as a divinely appointed prophet and a historical character who figures prominently in modern scripture and in the restoration of priesthood keys in the latter-days.

What thank they the Jews for the Bible which they receive from them? … Do they remember the travails, and the labors, and the pains of the Jews, and their diligence unto me, in bringing forth salvation unto the Gentiles?

O ye Gentiles, have ye remembered the Jews, mine ancient covenant people? Nay; but ye have cursed them, and have hated them, and have not sought to recover them.

Thou fool, that shall say: A Bible, we have got a Bible, and we need no more Bible. Have ye obtained a Bible save it were by the Jews?

On the important place of the Bible in the faith of the Latter-day Saints, see, e.g., N. A. Maxwell, Living Scriptures; R. L. Millet, What the Bible Means. On the spiritual seriousness with which King James Bible translators undertook their task, see J. R. Clark, Jr., Why the KJV, pp. 418-420; K. P. Jackson, Coming Forth, pp. 52-56.

There are similar difficulties that have come into play in the textual, editing, and publishing history of the Book of Mormon and the Doctrine and Covenants (e.g., Section 27), a fact that should help us better understand the idea of a textual history described by source criticism for the Old Testament. As Ben McGuire explains (B. L. McGuire, 17 March 2014):

Within the short history of our scripture we see numerous such changes (even with the existence of printing technology) that help us to understand that these changes occur quite naturally—and are not necessarily the results of translational issues or corrupt priests. We can, of course, completely identify the history of some of these changes, we can detail corruptions in the Book of Mormon that have occurred from the original manuscript. We can speculate about the existence of these errors where the original manuscript does not exist, and so on. And the fact that we can talk about [D&C] 27 as a composite work is itself another symptom of the process by which our texts come into existence in a way that doesn’t reflect a single author with a single pen, providing us with the perfect word of God.

The Christian world accepts the Bible as the word of God. Most have no idea of how it came to us.

I have just completed reading a newly published book by a renowned scholar. It is apparent from information which he gives that the various books of the Bible were brought together in what appears to have been an unsystematic fashion. In some cases, the writings were not produced until long after the events they describe. One is led to ask, “Is the Bible true? Is it really the word of God?”

We reply that it is, insofar as it is translated correctly. The hand of the Lord was in its making.

Robert F. Smith, http://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/sorting-out-the-sources-in-scripture/#comment-13917, 6 March 2014 observes that “ancient Near Eastern creation stories generally differ in details, but agree in the broad schema—as Speiser shows in his Anchor Bible translation-commentary on Genesis (E. A. Speiser, Genesis, pp. 9-13). The same is true of the various Flood and Tower stories. … What would be truly odd would be the lack of divergent accounts.”

What Can Be Learned from Comparing the Book of Moses to Ancient Texts?

There are a variety of comparative approaches that can be used to understand the texts and translations of modern scripture. For example, in the Book of Moses Essays we are interested in comparing Latter-day Saint scripture with ancient sources unknown to Joseph Smith in support of arguments that the Prophet translated through a process that was dependent on divine revelation.[91] On the other hand, some comparative studies seek to identify instances where Joseph Smith might have drawn on the Bible and other resources known to him as aids in translation. Yet other studies analyze intertextuality between the Bible and modern scripture with the goal of recognizing and understanding the interplay of these texts, while generally setting aside questions about the translation process.

There is still much to be learned about the texts and translation of modern scripture, and more research is needed along all these lines.[92] But the primary focus of the Book of Moses Essays and related resources is to describe how the Book of Moses appears to parallel (and sometimes invert) extant narrative elements of ancient descriptions found elsewhere. When the totality of these ancient connections are considered, it seems highly implausible that Joseph Smith possessed the detailed knowledge necessary to create such a text, or that it was cut out of whole cloth from some combination of his background and his imagination.

Of course, current evidence suggests that Joseph Smith was not entirely bound to a character-by-character, word-by-word reproduction of a source text in all of his translation work.[93] But we consider the text’s significant patterns of resemblance and unexpected conformance to ancient manuscripts that the Prophet could not have known as potential indicators of antiquity, and that these are best explained when the essential element of divine revelation is acknowledged.[94]

Though comparative research can never prove a particular interpretation of the text, it can certainly rule out some and suggest others.[95] In addition, we are persuaded that the process of careful comparison can increase understanding and appreciation of otherwise obscure details in both ancient and modern texts.

The capacity of scholars to appreciate God’s historical presence does not depend on an ability to share their subjects’ faith in God’s actual presence. Over two decades have passed since Edmund Morgan brilliantly demonstrated how one might consider the very “real” influence in history of even the most “fictional” sovereigns. Part of the genius displayed by Morgan’s mentor, Perry Miller, was the ability of an avowed atheist to let God play a starring role in his subjects’ lives. In an essay that continues to draw me in seven decades after its publication — and after countless efforts at criticism, including my own — Miller tried to divert scholarly attention away from prevailing interest in Emerson’s thought on capitalist economics, or Thoreau’s potent critique of American aggression against Mexico, and toward their ideas about communing with the divine. He did so with a warning to those who would rather not bother with such ethereal things: “Our age has the tendency,” Miller wrote, “to amputate whatever we find irrelevant form what the past itself considered the body of its teaching.” The thoroughly skeptical Miller did not care much for the content of his subjects’ metaphysics, nor was he insensitive to religion’s historical uses as an instrument of social control and social protest, but his work remains a powerful witness to the fact that serious effort to understand “human strainings to raise God’s veil” only enriches our ability to comprehend the people of the past.

Does the Book of Moses Have a Basis in History?

Though the historicity of some characters in the Bible might be reasonably questioned, so far as we have been able to determine in the case of modern scripture, named figures from ancient times are consistently represented as historical individuals.

On what basis should determinations about the historicity of scriptureal characters be made? According to John Walton and Brent Sandy, when determining whether the “people and events portrayed in narrative about the real past are fictional or literary constructs,” our decisions “must be driven by our best assessments of what the biblical narrator intended. … We may still find reason to discuss whether the author of Job intends every part of the book to represent real events in a real past or whether it is literature built around a historical core. The point is that any conclusion that seeks to maintain authority will conform to the demonstrable intentions of the narrator.”[96]

Some scholars have come to the conclusion that there is little of genuine value that can be gleaned by comparing modern scripture to writings from antiquity. In part, this is due to the fact that comparative studies sometimes have been conducted carelessly. However, a more important reason for the reluctance of some to embrace the comparative method is that they may see little or nothing of historical value in either the scriptural productions of Joseph Smith or in ancient traditions preserved inside and outside the Bible. If both the Moses of modern scripture and the Moses of ancient Near East tradition are largely, if not exclusively, literary rather than historical figures, why would a detailed comparison of their stories reveal anything real about the material past?

While imperfections in the Bible will not greatly disturb or surprise most Latter-day Saints, their belief that the principal events and characters described in modern scripture have a basis in history and revelation is of great consequence to their faith. How so?

- First, Joseph Smith claimed to have met and conversed with many of these characters;[97]

- Second, many ancient figures mentioned in modern scripture are presented at face value as historical characters in historical settings;

- Finally, and most importantly, some of these individuals are recorded as having personally transmitted priesthood authority and keys to Joseph Smith.

For these reasons, those who believe that Joseph Smith met, conversed with, wrote about, spoke about, and was given authority by divinely sent personages who formerly lived on earth, also embrace by implication the idea that authentic history sits behind the records of the Prophet’s visions, teachings, translations, and revelations.

Book of Mormon figures personally known to Joseph Smith include Lehi, Nephi, Moroni, and apparently others. See ibid., pp. 129–131.

For a useful collection of additional accounts of divine manifestations to the Prophet, see J. W. Welch et al., Opening, Opening.

Is the Book of Moses a Work of Pseudepigrapha?

In a discussion on scripture authorship, it is appropriate to introduce another class of ancient writings known today as pseudepigrapha. James Charlesworth notes that the term “pseudepigrapha” (literally “with false superscription”[98]) has a “long and distinguished history,”[99] with changes in the way it has been applied to various writings over the years that mirror major shifts in the general field of biblical studies itself.[100] The definition in the American Heritage Dictionary is “spurious or pseudonymous writings, especially Jewish writings ascribed to various biblical patriarchs and prophets.”[101] Importantly, however, the tenor of these definitions would seem to exclude the following situation:[102]

For example, if the sixth-century Daniel[103] was the authority figure who gave oracles that were duly recorded in documents that were saved until the second century, when someone compiled them into the book we have now and perhaps even included some updated or more specific information (provided by recognized authority figures in that time), that would not constitute pseudepigraphy or false attribution.[104] If that sort of process was an accepted norm, the attribution claims are not as specific and comprehensive as we may have thought when we were using more modern models of literary production. Authority is not jeopardized as long as we affirm the claims that the text is actually making using models of understanding that reflect the ancient world.

Considerable diversity of opinions regarding the specific revelatory process by which Joseph Smith translated the Book of Mormon and works attributed to Moses and Abraham is accommodated among Latter-day Saint scholars.[105] But opinions that affirm these books as containing divine truths, while being falsely attributed to those two prophets are understandably difficult for most members of the Church to accept.

Another difficulty with a description of the Book of Moses as merely an inspired pseudepigraphon is that it tends to paint Latter-day Saint readers into discrete camps. As a label, the term “pseudepigrapha” has an all-or-nothing feel. For that reason, it fails to capture a more nuanced view that could allow for the possibility of not only significant theological connections with ancient Israel but also authentic historical material reflecting memories of events in the lives of Moses and Abraham embedded in the text that Joseph Smith produced (even though he produced it in the nineteenth century). The result of this oversimplification is a sort of caricature that doesn’t fit well with relevant scholarship on these books. Classing the entire Book of Moses with a single label obscures the complex nature of the translation process and the work that resulted from it,[106] just as study of the Bible without taking into account its multiple sources obscures its richness.

Of course, what is most at stake here in the use of the label pseudepigrapha to describe the book of Moses is authority. While the term “pseudepigrapha” may be a useful construct for textual studies, it doesn’t work as well for the characterization of scripture, where the question of authority is far more significant. Latter-day Saints recognize authority in works of modern scripture because they were produced by a modern prophet, without having to establish a priori that their every word or phrase has a direct correlation to the words of authorities from ancient times.

In his volume on the translation of the Book of Mormon, Brant Gardner summarizes a perspective that bounds his views of the conceptual distance between plate text and its English translation. The ideas expressed are also relevant to Joseph Smith’s production of the book of Moses:[107]

The most extreme version of a conceptual theory of translation would make the plates extremely remote and essentially unrelated to the English text. It might even suggest that it was not really a translation, but simply a story based on real events.

The danger of that slippery slope is apparent in the way [Elder John A.] Widtsoe applied the brakes by declaring Joseph’s text “far beyond” his normal capabilities. That same desire to set the brakes while accepting some distance between the plate text and the translation can be seen in Robert Millet’s description of the process.

Gardner cites Millet’s apt summary as follows:[108]

We need not jump to interpretive extremes because the language found in the Book of Mormon (including that from the Isaiah sections or the Savior’s sermon in 3 Nephi) reflects Joseph Smith’s language. Well, of course it does! The Book of Mormon is translation literature: practically every word in the book is from the English language. For Joseph Smith to use the English language with which he and the people of his day were familiar in recording the translation is historically consistent. On the other hand, to create the doctrine (or to place it in the mouths of Lehi or Benjamin or Abinadi) is unacceptable. The latter is tantamount to deceit and misrepresentation; it is, as we have said, to claim that the doctrines and principles are of ancient date (which the record itself declares) when, in fact, they are a fabrication (albeit an “inspired” fabrication) of a nineteenth-century man. I feel we have every reason to believe that the Book of Mormon came through Joseph Smith, not from him. Because certain theological matters were discussed in the nineteenth century does not preclude their revelation or discussion in antiquity.

Is the Book of Moses Compatible With Science?

Given their status as targets of humor and caricature, the well-worn stories of Adam, Eve, and Noah are sometimes difficult to take seriously, even for some Latter-day Saints. However, a thoughtful examination of the scriptural record of these characters will reveal not simply tales of “piety or … inspiring adventures”[109] but rather carefully crafted narratives from a highly sophisticated culture that preserve “deep memories”[110] of revealed truths. We do an injustice both to these marvelous records and to ourselves when we fail to pursue an appreciation of scripture beyond the initial level of cartoon cut-outs inculcated upon the minds of young children.[111]

Though the reader should be referred to more comprehensive works for responses to specific questions about events in the Book of Moses,[112] we will draw on perspectives from the work of Latter-day Saint philosopher and scripture scholar James E. Faulconer as a useful starting point for those seeking to understand the relationship between science and scripture.

The Prophet Joseph Smith held the view that scripture should be “understood precisely as it reads.”[113] It must be realized, however, that what pre-modern peoples understood to be “literal” interpretations of scripture are not the same as what most people understand them to be in our day. Whereas modernists[114] typically apply the term “literal” to accounts that provide clinical accuracy in the journalistic dimensions of who, what, when, and where, premoderns were more apt to understand “literal” in the sense of “what the letters, i.e., the words say.” These are two very different modes of interpretation. As Faulconer observed: “‘What x says’ [i.e., the premodern idea of “literal”] and ‘what x describes accurately’ [i.e., the modernist idea of “literal”] do not mean the same, even if the first is a description.”[115]

Faulconer argues that insistence on a “literal” interpretation of sacred events, in the contemporary clinical sense of the term, may result in “rob[bing that event] of its status as a way of understanding the world.”[116] Elaborating more fully on the limitations of modernist descriptions of scriptural events, he observes that the interest of premoderns:[117]

was not in deciding what the scriptures portray , but in what they say. They do not take the scriptures to be picturing something for us, but to be telling us the truth of the world, of its things, its events, and its people, a truth that cannot be told apart from its situation in a divine, symbolic ordering.[118]

Of course, that is not to deny that the scriptures tell about events that actually happened. … However, premodern interpreters do not think it sufficient (or possible) to portray the real events of real history without letting us see them in the light of that which gives them their significance—their reality, the enactment of which they are a part—as history, namely the symbolic order that they incarnate. Without that light, portrayals cannot be accurate. A bare description of the physical movements of certain persons at a certain time is not history (assuming that such bare descriptions are even possible).

“Person A raised his left hand, turning it clockwise so that .03 milliliters of a liquid poured from a vial in that hand into a receptacle situated midway between A and B” does not mean the same as “Henry poured poison in to Richard’s cup.” Only the latter could be a historical claim (and even the former is no bare description).

Of course, none of this should be taken as implying that precise times, locations, and dimensions are unimportant in scriptural stories. Indeed, details given in Genesis about, for example, the size of the Ark, the place where it landed, and the date of its debarkation are crucial to its interpretation. However, when such details are present, we can usually be sure that they are not meant merely to add a touch of realism to the account but rather to help the reader make mental associations with scriptural stories and religious concepts found elsewhere in the Bible.

In the case of Noah, for example, these associations might echo the story of Creation or might anticipate the Tabernacle of Moses. It is precisely such backward and forward reverberations of common themes in disparate passages of scripture, rather than a photorealistic rendering of the Flood, that will provide the understanding of these stories that we seek. Though we can no more reconstruct the story of Noah from the geology of flood remains than we can re-create the discourse of Abinadi from the ruins of Mesoamerican buildings, we are fortunate to have a scriptural record that can be “understood precisely as it reads.”[119]

A thumbnail characterization of this modernism controversy is given by Faulconer (J. E. Faulconer, Study, pp. 131–132):

One writer has described modernism’s assumption this way: “A constellation of positions (e.g., a rational demand for unity, certainty, universality, and ultimacy) and beliefs (e.g., the belief that words, ideas, and things are distinct entities; the belief that the world represents a fixed object of analysis separated from forms of human discourse and cognitive representation; the belief that culture is subsequent to nature and that society is subsequent to the individual)” (S. Daniel, Paramodern Strategies, pp. 42–43). There is far too little room here to discuss the point extensively, but suffice it to say that, first, few, if any, of these assumptions have remained standing in the twentieth century, and second, the failure of these assumptions does not necessarily imply the failure of their claims to truth or knowledge, as is often argued, sometimes by adherents to the current attack on modernism and sometimes by critics of that attack. For an excellent discussion of postmodernism and its relation to religion, see J. Caputo, Good News.

Is the Book of Moses a Temple Text?

John W. Welch defines a “temple text”:[120]

as one that contains the most sacred teachings of the plan of salvation that are not to be shared indiscriminately, and that ordains or otherwise conveys divine powers through ceremonial or symbolic means together with commandments received by sacred oaths that allow the recipient to stand ritually in the presence of God. Several such texts are found in the Book of Mormon. In addition to the text of Ether 1–4 regarding the Brother of Jared, the most notable are Jacob’s speech in 2 Nephi 6–10, Benjamin’s speech in Mosiah 1–6, Alma 12–13 and 3 Nephi 11–18.

In modern temples, the posterity of Adam and Eve trace the footsteps of their first parents—first as they are sent away from Eden and later in their subsequent journey of return and reunion.[121] Because the Latter-day Saint temple endowment explicitly presents the story of Adam and Eve, it is already obvious to endowed members of the Church that the Book of Moses is the temple text par excellence in scripture. What may be new to them, however, is that the temple themes in the Book of Moses extend beyond the story of Adam and Eve to their culmination in the story of Enoch. While Moses 2–4 tells the story of the “down-road,” Moses 5–7 follows the journey of Adam and Eve and the righteous branches of their posterity along the “up-road.”[122]

More specifically, stories in the later chapters of the Book of Moses, following the precedent of the account of Adam and Eve, illustrate specific temple covenants that are unfolded chapter by chapter in the sequence that would be expected by endowed Latter-day Saints. Indeed, Mark Johnson goes so far as to suggest that temple covenant-making themes in former times helped dictate both the structure and the content of the material selected for inclusion in the Book of Moses.[123]

Moses 1 can best be understood as a prelude to the temple text in Moses 2–8. Both the overall narrative structure and many details within Moses 1 place it squarely in the genre of the ancient heavenly ascent literature.[124] Temple-going Latter-day Saints who read accounts of heavenly ascent will quickly discover that the structure and symbols found in such stories are strongly related to the theology and rites of the temple.[125] However, while stories of heavenly ascent bear important similarities to ancient and modern temple liturgy, they make the claim of being something more. Whereas temple rituals dramatically depict a figurative journey into the presence of God, the heavenly ascent literature contains stories of exceptional individuals who experienced actual encounters with Deity within the heavenly temple[126]—the “completion or fulfillment” of the “types and images” found in earthly ordinances.[127]

In light of pervasive temple themes throughout the Book of Moses, it is significant that it was revealed to Joseph Smith more than a decade before the full temple endowment was administered to others in Nauvoo.[128]

David Calabro provides well-reasoned arguments for the Book of Moses as a temple text from a slightly different but compatible angle (D. Calabro, Joseph Smith and the Architecture). See also J. W. Welch, Priestly Interests.

In Summary, What Should We Make of the Book of Moses?

The resources on this website constitute a witness that the Book of Moses is a priceless prophetic reworking of the book of Genesis, made with painstaking effort under divine direction. A focused study of this book of scripture will reveal the extent to which its words reverberate with echoes of antiquity—and, no less significantly, with the deepest truths of our personal experience. Although neither “complete” nor “inerrant,” it is a text of inestimable value that merits focused, lifelong study.

Writing about the unrevealed portions of the Book of Abraham, Hugh Nibley reminds us of lessons that also apply to the Book of Moses:

Important parts of the Pearl of Great Price which are still being held back include “writings that cannot be revealed unto the world; but is [sic] to be had in the holy Temple of God,”[129] “ought not to be revealed at the present time.”[130] Years ago, when we cited some passages from what we called an Egyptian endowment,[131] without elaborating, many Latter-day Saints quietly recognized their own temple endowment. Important things are still expressly withheld which “ought not to be revealed at the present time.” … For some of the secrets there is a standing invitation: “If the world can find out these numbers, so let it be. Amen.”[132] That was over a century and a half ago, and the invitation to search is still open.[133]

References

American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (Fourth Edition, 2000). In Bartleby.com. http://www.bartleby.com/61/. (accessed April 26, 2009).

Andersen, F. I. "2 (Slavonic Apocalypse of) Enoch." In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. 2 vols. Vol. 1, 91-221. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Bachman, Danel W. "New light on an old hypothesis: The Ohio origins of the revelation on eternal marriage." Journal of Mormon History 5 (1978): 19-32.

Bailey, David H., Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, John H. Lewis, Gregory L. Smith, and Michael L. Stark, eds. Science and Mormonism: Cosmos, Earth, and Man. Interpreter Science and Mormonism Symposia 1. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2016.

Bakhos, Carol. "Genesis, the Qur’an and Islamic interpretation." In The Book of Genesis: Composition, Reception, and Interpretation, edited by Craig A. Evans, Joel N. Lohr and David L. Petersen. Supplements to Vetus Testamentum, Formation and interpretation of Old Testament Literature 152, eds. Christl M. Maier, Craig A. Evans and Peter W. Flint, 607-32. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2012.

Barker, Margaret. The Hidden Tradition of the Kingdom of God. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), 2007.

Barlow, Philip L. 1991. Mormons and the Bible: The Place of the Latter-day Saints in American Religion. Updated ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Barney, Kevin L. 2014. Authoring the Old Testament. In By Common Consent. http://bycommonconsent.com/2014/02/23/authoring-the-old-testament/ Page. (accessed March 15, 2014).

Bauckham, Richard, James R. Davila, Alex Panayotov, and James H. Charlesworth, eds. Old Testament Pseudepigrapha: More Noncanonical Scriptures. 2 vols. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2013.

Bednar, David A. "Faithful parents and wayward children: Sustaining hope while overcoming misunderstanding." Ensign 44, March 2014, 28-33.

Benson, Ezra Taft. "The Book of Mormon—Keystone of our religion." Ensign 16, November 1986, 4-7. https://www.lds.org/ensign/1986/11/the-book-of-mormon-keystone-of-our-religion?lang=eng. (accessed March 20, 2014).

Bokovoy, David E. Authoring the Old Testament: Genesis-Deuteronomy. Contemporary Studies in Scripture. Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2014.

Bowen, Matthew L. "‘What thank they the Jews?’." In Name as Key-Word: Collected Essays on Onomastic Wordplay and the Temple in Mormon Scripture, edited by Matthew L. Bowen, 69-81. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2018.

———. E-mail message to Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, February 26, 2020.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. Ancient and Modern Perspectives on the Book of Moses. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Publishing, 2010.

———. Creation, Fall, and the Story of Adam and Eve. 2014 Updated ed. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014.

———. "The LDS book of Enoch as the culminating story of a temple text." BYU Studies 53, no. 1 (2014): 39-73. http://www.templethemes.net/publications/140224-a-Bradshaw.pdf. (accessed September 19, 2017).

———. "Sorting out the sources in scripture. (Review of David E. Bokovoy, Authoring the Old Testament: Genesis-Deuteronomy)." Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 9 (2014): 215-72.

———. Temple Themes in the Book of Moses. 2014 update ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Publishing, 2014.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. "Freemasonry and the Origins of Modern Temple Ordinances." Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 15 (2015): 159-237. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/freemasonry-and-the-origins-of-modern-temple-ordinances/. (accessed May 20, 2016).

———. "Foreword." In Name as Key-Word: Collected Essays on Onomastic Wordplay and the Temple in Mormon Scripture, edited by Matthew L. Bowen, ix-xliv. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2018.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., David J. Larsen, and Stephen T. Whitlock. "Moses 1 and the Apocalypse of Abraham: Twin sons of different mothers?" Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 36 (2020): in press.

Brown, S. Kent, Victor L. Ludlow, Robert J. Matthews, and C. Wilfred Griggs. "The Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible: A panel." In Scriptures for the Modern World, edited by Paul R. Cheesman and C. Wilfred Griggs. Religious Studies Monograph Series 11, 75-98. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1984.

Bushman, Richard Lyman. Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling, A Cultural Biography of Mormonism’s Founder. New York City, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005.

———. Mormonism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Calabro, David. "Joseph Smith and the architecture of Genesis." In The Temple: Ancient and Restored. Proceedings of the 2014 Temple on Mount Zion Symposium, edited by Stephen D. Ricks and Donald W. Parry. Temple on Mount Zion 3, 165-81. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2016. https://interpreterfoundation.org/conferences/2014-temple-on-mount-zion-conference/2014-temple-on-mount-zion-conference-videos/. (accessed October 27, 2014).

Cannon, George Q. 1888. The Life of Joseph Smith, the Prophet. Second ed. Salt Lake City, UT: The Deseret News, 1907.

Caputo, John. "The good news about alterity: Derrida and theology." Faith and Philosophy 10, no. 4 (October 1993): 453-70.

Carr, David M. The Formation of the Hebrew Bible: A New Reconstruction. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Charlesworth, James H., ed. The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha. 2 vols. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983. http://ocp.acadiau.ca/. (accessed September 20).

Clark, E. Douglas. "A prologue to Genesis: Moses 1 in light of Jewish traditions." BYU Studies 45, no. 1 (2006): 129-42.

Clark, J. Reuben, Jr. 1956. Why the King James Version. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1979.

Clarke, Adam. The Holy Bible Containing the Old and New Testaments. New York City, NY: N. Bangs and J. Emory, for the Methodist Eposcopal Church, 1825. https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Holy_Bible_Containing_the_Old_and_Ne.html?id=Lds8AAAAYAAJ. (accessed February 19, 2020).

Daniel, Steven. "Paramodern strategies of philosophical historiography." Epoché: A Journal for the History of Philosophy 1, no. 1 (1993): 41-63.

Dirkmaat, Gerrit. "Great and marvelous are the revelations of God." Ensign 43, January 2013, 55-59.

Doctrine and Covenants of the Church of the Lattter Day Saints: Carefully Selected from the Revelations of God and Compiled by Joseph Smith Junior, Oliver Cowdery, Sidney Rigdon, Frederick G. Williams (Presiding Elders of said Church). Kirtland, OH: F. G. Williams & Co., 1835. Reprint, Herald House publishing division of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, Independence, Missouri, 1971.

Eusebius. ca. 325. The History of the Church. Translated by G. A. Williamson and Andrew Louth. London, England: Penguin Books, 1989.

Evening and Morning Star. Independence, MO and Kirtland, OH, 1832-1834. Reprint, Basel Switzerland: Eugene Wagner, 2 vols., 1969.

Faulconer, James E. Scripture Study: Tools and Suggestions. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, Brigham Young University, 1999.

———. "Scripture as incarnation." In Historicity and the Latter-day Saint Scriptures, edited by Paul Y. Hoskisson, 17-61. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Religious Studies Center, 2001. Reprint, in Faulconer, J. E. Faith, Philosophy, Scripture. Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute, Brigham Young University, 2010, pp. 151-202.

———. "Response to Professor Dorrien." In Mormonism in Dialogue with Contemporary Christian Theologies, edited by Donald W. Musser and David L. Paulsen, 423-35. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2007.

Faulring, Scott H., Kent P. Jackson, and Robert J. Matthews, eds. Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible: Original Manuscripts. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2004.

Faulring, Scott H., and Kent P. Jackson, eds. Joseph Smith’s Translation of the Bible Electronic Library (JSTEL) CD-ROM. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University. Religious Studies Center, Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2011.

First Presidency of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. "Letter Reaffirms Use of King James Version." LDS Church News, June 20 1992, Z3. http://www.desnews.com. (accessed September 7).

Flake, Kathleen. "Translating time: The nature and function of Joseph Smith’s narrative canon." Journal of Religion 87, no. 4 (October 2007): 497-527. https://www.academia.edu/244675/_Translating_Time_The_Nature_and_Function_of_Joseph_Smiths_Narrative_Canon_. (accessed February 22, 2009).

Friedman, Richard Elliott. The Hidden Book in the Bible. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, 1998.

———, ed. Commentary on the Torah. New York, NY: HarperCollins, 2001.

———. 1987. Who Wrote the Bible? San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, 1997.

Gardner, Brant A. The Gift and Power: Translating the Book of Mormon. Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2011.

———. "Literacy and orality in the Book of Mormon." Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 9 (2014): 29-84.

Gee, John. A Guide to the Joseph Smith Papyri. Provo, UT: FARMS at Brigham Young University, 2000.

Hatch, Trevan G. Visions, Manifestations, and Miracles of the Restoration. Orem, UT: Granite Publishing, 2008.

Hauglid, Brian M., and Ray L. Huntington. "A Community of Christ perspective on the JST research of Robert J. Matthews: An interview with Ronald E. Romig." The Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel 5, no. 2 (2004): 49-55.https://rsc.byu.edu/vol-5-no-2-2004/community-christ-perspective-jst-research-robert-j-matthews-interview-ronald-e. (accessed September 1).

Hendel, Ronald S. "Historical context." In The Book of Genesis: Composition, Reception, and Interpretation, edited by Craig A. Evans, Joel N. Lohr and David L. Petersen. Supplements to Vetus Testamentum, Formation and interpretation of Old Testament Literature 152, eds. Christl M. Maier, Craig A. Evans and Peter W. Flint, 51-81. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2012.

Himmelfarb, Martha. Ascent to Heaven in Jewish and Christian Apocalypses. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Hinckley, Gordon B. "The great things which God has revealed." Ensign 35, May 2005, 80-83.

Holland, David F. Sacred Borders: Continuing Revelation and Canonical Restraint in Early America. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Hunt, Jeffrey M., R. Alden Smith, and Fabio Stok. Classics from Papyrus to the Internet: An Introduction to Transmission and Reception. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2017. https://books.google.com/books?id=6-zaDgAAQBAJ. (accessed March 19, 2020).

Huntington, Ray L., and Brian M. Hauglid. "Robert J. Matthews and his work with the Joseph Smith Translation." The Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel 5, no. 2 (2004): 23-47. https://rsc.byu.edu/vol-5-no-2-2004/community-christ-perspective-jst-research-robert-j-matthews-interview-ronald-e. (accessed September 1).

Isaac, E. "1 (Ethiopic Apocalypse of) Enoch." In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. Vol. 1, 5-89. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Isenberg, Wesley W. "The Gospel of Philip (II, 3)." In The Nag Hammadi Library, edited by James M. Robinson. 3rd, Completely Revised ed, 139-60. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, 1990.

Jackson, Kent P. "Joseph Smith’s Cooperstown Bible: The Historical Context of the Bible Used in the Joseph Smith Translation." BYU Studies 40, no. 1 (2001): 41-70. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol40/iss1/3/. (accessed April 25, 2020).

Jackson, Kent P., and Peter M. Jasinski. "The process of inspired translation: Two passages translated twice in the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible." BYU Studies 42, no. 2 (2003): 35-64.

Jackson, Kent P. The Book of Moses and the Joseph Smith Translation Manuscripts. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Religious Studies Center, 2005. https://rsc.byu.edu/archived/book-moses-and-joseph-smith-translation-manuscripts. (accessed August 26, 2016).

———. "The coming forth of the King James Bible." In The King James Bible and the Restoration, edited by Kent P. Jackson, 43-60. Provo, UT and Salt Lake City, UT: Brigham Young University Religious Studies Center and Deseret Book, 2011.

———. "The King James Bible and the Joseph Smith Translation." In The King James Bible and the Restoration, edited by Kent P. Jackson, 197-211. Provo, UT and Salt Lake City, UT: Brigham Young University Religious Studies Center and Deseret Book, 2011.

Jessee, Dean C. "The writing of Joseph Smith’s history." BYU Studies 11 (Summer 1971): 439-73.

Johnson, Mark J. “The lost prologue: Reading Moses Chapter One as an Ancient Text.” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 36 (2020): 145-86. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/the-lost-prologue-reading-moses-chapter-one-as-an-ancient-text/. (accessed June 5, 2020).

Jones, Gerald E. "Apocryphal literature and the Latter-day Saints." In Apocryphal Writings and the Latter-day Saints, edited by C. Wilfred Griggs. Religious Studies Monograph Series 13, 19-33. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1986.

Kee, Howard C. "Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs." In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. Vol. 1, 775-828. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Khalidi, Tarif, ed. The Muslim Jesus: Sayings and Stories in Islamic Literature. Convergences: Inventories of the Present, ed. Edward E. Said. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Kimball, Spencer W., N. Eldon Tanner, and Marion G. Romney. 1978. "Statement of the First Presidency: God’s Love for All Mankind (February 15, 1978), excerpted in S. J. Palmer article on ‘World Religions, Overview’." In Encyclopedia of Mormonism, edited by Daniel H. Ludlow. 4 vols. Vol. 4, 1589. New York City, NY: Macmillan, 1992. http://www.lib.byu.edu/Macmillan/. (accessed November 26).

Kraft, Robert A. "The pseudepigrapha in Christianity." In Tracing the Threads: Studies in the Vitality of Jewish Pseudepigrapha, edited by John C. Reeves, 55-86. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1994.

Kugel, James L. "Some instances of biblical interpretation in the hymns and wisdom writings of Qumran." In Studies in Ancient Midrash, edited by James L. Kugel, 155-69. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

LaCocque, André. The Trial of Innocence: Adam, Eve, and the Yahwist. Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2006.

LDS Bible Dictionary. In LDS Scriptures. https://www.lds.org/scriptures/bd/prayer?lang=eng. (accessed February 28, 2018).

Lipscomb, W. Lowndes, ed. The Armenian Apocryphal Literature. University of Pennsylvania Armenian Texts and Studies 8, ed. Michael E. Stone. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania, 1990.

Matthews, Robert J. "A Plainer Translation": Joseph Smith’s Translation of the Bible—A History and Commentary. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1975.

———. 1992. "How Joseph Smith Translation passages were selected for the LDS Bible." In Selected Writings of Robert J. Matthews, edited by Robert J. Matthews. Gospel Scholars Series, 312-13. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1999.

Maxwell, Neal A. "Living scriptures from a living God through living prophets and for a living Church." In Scriptures for the Modern World, edited by Paul R. Cheesman and C. Wilfred Griggs. Religious Studies Monograph Series 11, 1-12. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1984.

McConkie, Bruce R. Doctrines of the Restoration: Sermons and Writings of Bruce R. McConkie. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1989.

McConkie, Rebecca L. ""A miracle from day one": Publication of the Joseph Smith Translation manuscripts." The Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel 5, no. 2 (2004): 13-21. https://rsc.byu.edu/vol-5-no-2-2004/community-christ-perspective-jst-research-robert-j-matthews-interview-ronald-e. (accessed September 1).

McGuire, Benjamin L. E-mail message to Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, 17 March, 2014.

———. E-mail message to Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, 15 August, 2017.