Review of Cheryl L. Bruno, Joe Steve Swick III, and Nicholas S. Literski, Method Infinite: Freemasonry and the Mormon Restoration (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2022). 544 pages. $44.95 (hardback); $34.95 (softcover).

Abstract: There is much to celebrate in this important new study of Freemasonry and the Latter-day Saints. To their credit, the authors have succeeded in creating a work that is richer than earlier studies of the subject, probing many previously unexplored hints of Masonic influence on Latter-day Saint life and thought from the beginning of the Restoration through the end of the nineteenth century. That said, the book’s dauntingly broad survey suffers from uneven quality on some of the many topics it ambitiously tackles. While recognizing the study’s considerable merits, its shortcomings must also be considered. For this reason, I’ve divided this review into three parts: What’s Good, What’s Questionable, and What’s Missing. I conclude with methodological observations about best practices in the use of the comparative analysis in studies of important and challenging subjects such as this one.

Two paragraphs from the early pages of the book provide, perhaps, the best way to understand the authors’ objectives in proper perspective:

While no one thing can entirely explain the rise of Mormonism, the historical influence of Freemasonry on this religious tradition cannot be refuted. This work … offers a fresh perspective [Page 224]on the relationship between Freemasonry and the Mormon restoration. It asserts that the Mormon prophet’s firsthand knowledge of and experience with both Masonry and anti-Masonic currents contributed to the theology, structure, culture, tradition, history, literature, and ritual of the church he founded. There is a Masonic thread in Mormonism from its earliest days. …

As an adult, Smith relied on Masonry as one of the primary lenses and means by which he sought to approach God and restore true religion. Yet this aspect of his work has been abandoned by his modern-day followers. Masonry in Mormonism has been placed upon the woodpile.1

Consistent with the ambitious agenda summarized in this paragraph above, I hope that this review will persuade readers that there is much to celebrate in this important new study of Freemasonry and the Latter-day Saints. Cheryl Bruno’s well-crafted prose and her personal research contributions build on the copious investigations and preliminary writing of Nicolas S. Literski, JD, PhD, that began two decades ago. Joe Steve Swick III, for his part, contributed knowledge of the breadth and depth of the larger Masonic history that made an enormous difference in the final product.

To their credit, the authors have succeeded in creating a work that is richer than earlier studies of the subject, probing many previously unexplored hints of Masonic influence on Latter-day Saint life and thought from the beginning of the Restoration through the end of the nineteenth century.

That said, the book’s dauntingly broad survey suffers from uneven quality on some of the many topics it ambitiously tackles. While recognizing the study’s considerable merits, its shortcomings must also be taken into account. For this reason, I’ve divided the review into three parts.

In the first part, entitled “What’s Good,” I will describe what I think are the strongest contributions of the book — namely, those that draw on primary historical sources relating to Freemasonry and the Latter-day Saints. Significantly, as part of their new contributions to the intersecting history of these groups, the authors have included little-known material on Masonic influences within nineteenth-century expressions of the Restoration outside of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Commendably, the authors have also highlighted the role of women in their discussion of Freemasonry, including perspectives [Page 225]on the organization and governance of the Relief Society. The attention given to the events surrounding the death and burial of Joseph Smith is also noteworthy.

Part two, entitled “What’s Questionable,” follows with a discussion of selected examples of portions of the book that rely on more tenuous evidence and arguments. The examples I have chosen are related to three topics: Joseph Smith’s early history, the perceived influence of Masonry on the translations and revelations of Joseph Smith, and the relationship of Freemasonry to the temple. These are controversial subjects and have generated a large amount of scholarly literature. On the one hand, the authors’ familiarity with the history and works of Freemasonry have allowed them to go further than any previous effort in unearthing possible connections with Latter-day Saint history and teachings. On the other hand, the book repeatedly invokes a handful argumentation patterns that often overstate the strength of perceived Masonic connections — sometimes explicitly, at other times implicitly. Table 1, at the beginning of part 2, classifies selected examples according to the faulty argumentation patterns they exemplify.

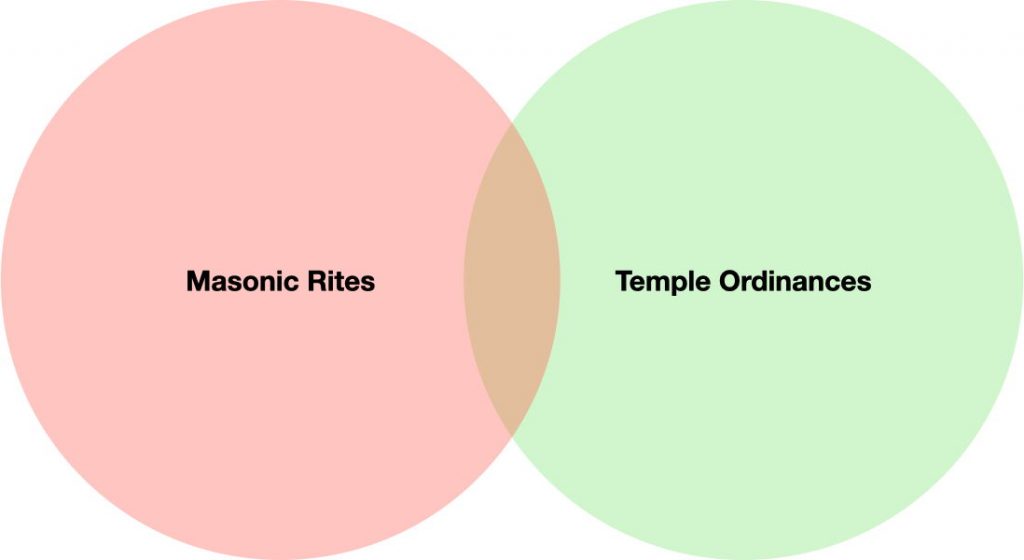

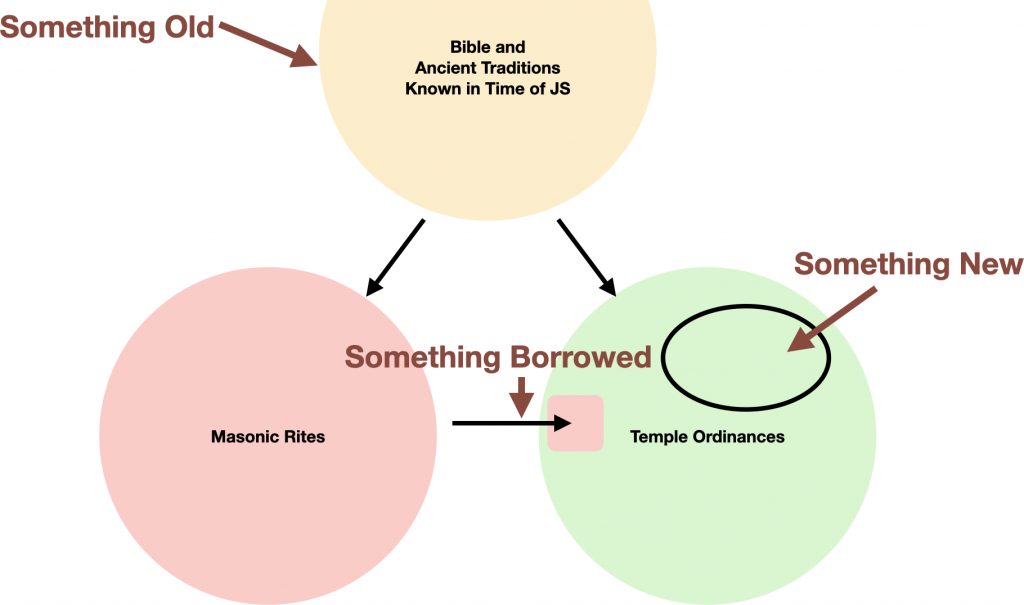

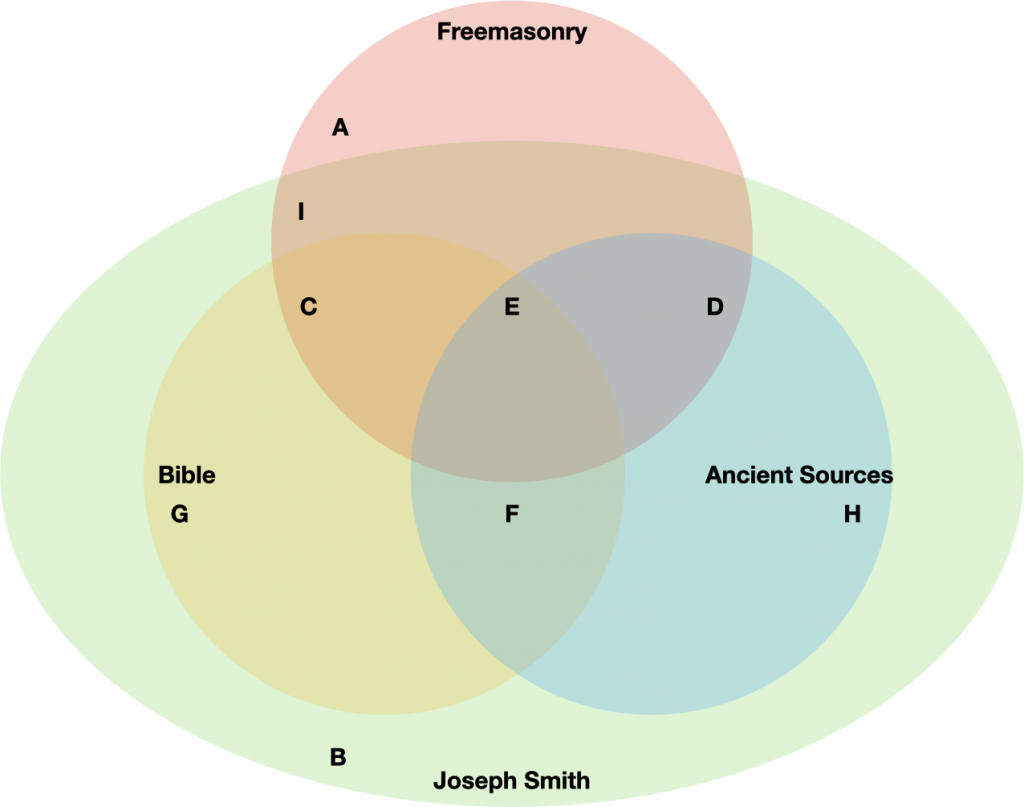

In part three, entitled “What’s Missing,” I apply some of the principles of scholarship relating to comparative analysis to help illuminate the relationship between Freemasonry and the temple ordinances, arguably the subject of greatest interest for the typical Latter-day Saint reader. No serious scholar today would deny that there is an important relationship between these rites, but the nature and extent of that relationship is a complex and frequently debated question. Adding to the difficulty in discerning this relationship is that, as the authors correctly observe, some Masonic features that were part of the Nauvoo endowment have been eliminated in modern temple ceremonies, “sometimes at the expense of what their Masonic origins might reveal to the thoughtful Latter-day Saint.”2 Further complicating the situation is that it is unknown whether any of the terminology and ritual dialogue patterns that are similar in Freemasonry and the temple ordinances were originally part of the endowment as given by Joseph Smith in the Red Brick Store or were introduced later as part of the revisions and standardization that occurred under the direction of Brigham Young.3

In addressing the relationship between Freemasonry and Nauvoo temple ordinances, Method Infinite makes the bold claim that Joseph Smith’s central project throughout his life was “restoring ancient Freemasonry” and he “believed his life to be the latter-day point and purpose for which that worldview existed.”4 But, as in every work of [Page 226]scholarship, that claim, like all others in the book, cannot stand on its own. Rather, it must be considered in light of the full spectrum of relevant information bearing on events, ideas, and their potential dependencies. Then, only after having considered in reasonable depth and breadth the entire ensemble of extant evidence, can scholars make the case for why their particular theory explains the most significant aspects of that body of data more completely and satisfactorily than the most likely competing hypotheses.

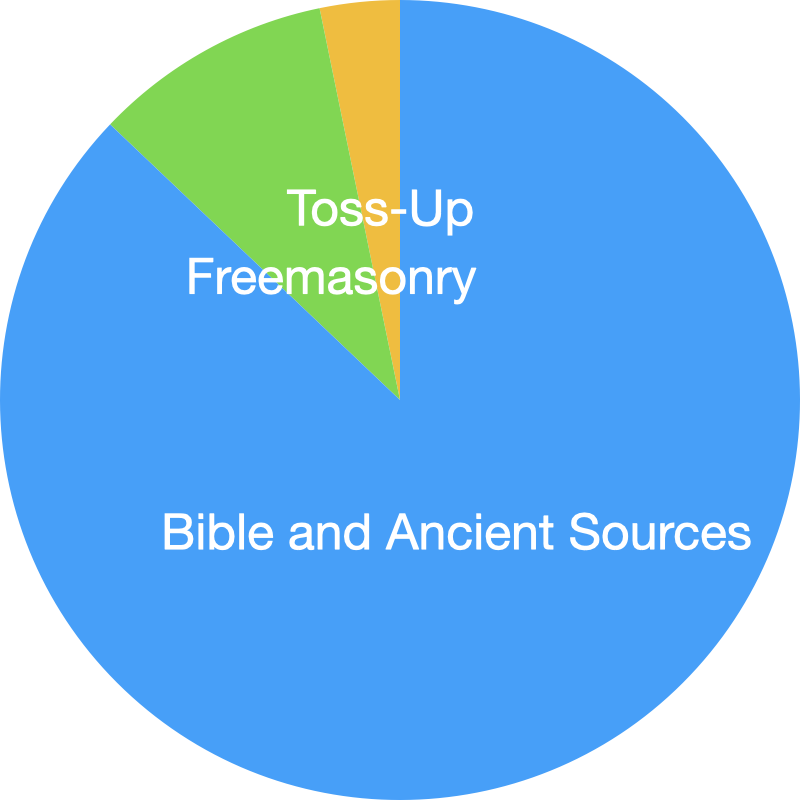

To help readers reach their own conclusions on the subject, I have summarized some of the most pertinent historical and source considerations relating to the origins of Latter-day Saint temple ordinances that are “missing” from the book in part three. I provide a simplified model illustrating the universe of possible dependencies among Freemasonry, the Bible, ancient sources, and nineteenth-century temple ordinances. To complete the picture, I summarize my personal judgments about the relative strengths of the similarities to and differences in the Nauvoo ordinances to these potential catalysts for temple-related revelations. In light of the results of comparative analysis, it is my view that while shared DNA between the rites of Freemasonry and those of modern temples is apparent — indicating both have some common ancestry in the Bible and also some nineteenth-century borrowing — Masonic and temple rituals are better characterized overall as distant cousins rather than members of the same nuclear family.

As a rationale for including what may seem to some readers a digression that goes beyond what is typical in a book review, I believe that helping readers of this essay become better acquainted with the tenets of comparative analysis sketched briefly in part three is valuable in its own right. I hope that exposure to the principles of comparative analysis will not only help them evaluate the comparisons between the ideas of Freemasonry and Latter-day Saint teachings made in Method Infinite, but that it will also serve the broader goal suggesting the kinds of improvements that could be made to the way scholars produce and readers evaluate comparative data that focuses on other important topics of Latter-day Saint history, theology, and scripture — thus, avoiding pitfalls and recognizing best practices.

By way of disclaimer, I should mention that I have recently written a book entitled Freemasonry and the Origins of Latter-day Saint Temple Ordinances,5 an expansion of a 2015 journal article6 I began to work on in the last half of 2021.7 After receiving a copy of Method Infinite earlier this year that was kindly provided by Loyd Ericson on behalf of Greg Kofford [Page 227]Books, I decided that in addition to writing a detailed review of Method Infinite, it would be relatively easy to turn my research on Freemasonry and the temple to into a book — expecting that I would be able to finish both the book and the review before beginning a lengthy period of travel beginning at the end of July. Wanting to make sure that I represented both the subject matter and the views of the authors of Method Infinite accurately and fairly, I contacted Cheryl Bruno and Nicholas S. Literski and let them know about both efforts. During the initial writing of the book, they kindly gave significant feedback on the chapters and provided helpful perspectives and answers to questions I had along the way. They also generously granted permission to publish quotations from their book and excerpts from their private communications with me. Earlier conversations with Joe Steve Swick III during the writing of the previous journal article had also been very helpful and supportive. I am grateful for the resultant friendly dialogue with these three scholars throughout the writing process.

As will be seen in this lengthy review, Method Infinite addresses an impressive breadth of subjects, and in most cases I had to start my research and writing about these many topics from scratch. As the authors had done previously with the book, they graciously provided feedback on an early draft of this review and have also had an opportunity to read and correct errors in a near-final version of this review. However, they did not attempt to do a thorough reading of the review, and I accept full responsibility for any remaining errors. I appreciate not only the scholarship of these authors but also their examples of how dialogue on differences need not jeopardize mutual respect and collegiality. I am also grateful for the efforts of other unnamed friends who have contributed their perspectives to this review.

1. What’s Good

The strongest portions of Method Infinite are those that draw directly from new discoveries and insights within the historical record — namely chapters 1, 3, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15, 17, and 18. Notably, the book cites many primary sources that have not appeared in comparable works and, in other cases, makes important corrections to them. In these historical sections, the book supersedes the previous groundbreaking but now incomplete and dated studies of Michael W. Homer.8 These are what I see as the significant strengths of Method Infinite and what makes the book an important new study of the subject:

- Valuable overview of Freemasonry (chapter 1)

- [Page 228]Solid history of the “Morgan affair” (chapter 3)

- Well-documented account of the reorganization of the Illinois Grand Lodge (chapter 11)

- Nuanced account of the establishment and controversies of the Nauvoo Lodge (chapter 11)

- Relatively complete history of all the Latter-day Saint Lodges (chapter 13)

- Masonic themes and precedents in the history of the Relief Society (chapter 12)

- Aspects of the founding of Nauvoo, though overreaches on Masonic themes (chapter 10)

- Summary of the death and burial of Joseph Smith (chapter 17)

- Good account of Masonic and quasi-Masonic activities in Utah and elsewhere (chapter 18)

- Well-crafted prose

- Relatively few typos

Chapter 1 gives a valuable overview of Freemasonry, starting with its prehistory in the traditions of operative stonemasons and ending with its nineteenth-century manifestations in America. Chapter 3 continues the story by providing a solid history of what has become known as the “Morgan affair.” This incident had significant consequences for nineteenth-century Freemasonry, especially in the period immediately preceding the establishment of the Nauvoo Lodge. In brief, an anti-Mason named William Morgan mysteriously disappeared and was probably murdered in 1826. The disappearance of Morgan was widely blamed on the Masons and became an issue of national importance. The shadow that this accusation cast on the fraternity — when added to false rumors that Masonry’s secrets were part of a broader conspiracy to undermine American government and ideals — led to a precipitous decline of membership that lasted for nearly two decades.

Following a hiatus, the Illinois Grand Lodge was reestablished in 1840, By that time, public indignation about the Morgan affair had had time to fade. When the Saints made application for a Nauvoo lodge in 1841, the Grand Lodge was already beginning to grapple with tensions between Masons who favored aggressive regrowth of the fraternity in the state and those who saw the race to establish new lodges as courting various dangers to the integrity of the organization. Among other feared consequences of unchecked growth during this tumultuous time was the initiation of men who were unworthy or unprepared for membership. This accusation, among others, dogged the incredibly fast-growing [Page 229]Latter-day Saint lodge in Nauvoo as well as additional Latter-day Saint lodges that eventually sprung up in the surrounding area.

Chapter 11 includes a well-documented account of the reorganization of the Illinois Grand Lodge. The chapter also chronicles the events that led to the establishment and initial controversies surrounding the Nauvoo Lodge. The authors provide a nuanced view of the accusations of Latter-day Saint apostate and critic John C. Bennett, distinguishing between those of Bennett’s claims likely to be false or exaggerated and those that had a plausible basis in actual events.9

Chapter 13 continues the story of the Nauvoo Lodge and documents with great care the establishment of additional Latter-day Saint Lodges in the surrounding areas. The authors also discuss the dedication of the Nauvoo Masonic Hall and various proposals for the establishment of a “Mormon Grand Lodge” because of the Saints’ sense of righteous indignation for the revocation of the provisional charter that had originally been granted to the Nauvoo Lodge.

In a notable contribution, chapter 12 reviews Masonic themes and precedents in the organization of the Relief Society, including a discussion of events relating to the introduction of plural marriage to various members of the society.

Chapter 10 is entitled “The Grand Design: Joseph’s Masonic Kingdom on the Mississippi.” The authors review the Saints’ accomplishments in the founding of Nauvoo and in the politics, economic, education, and social aspects of the rapidly expanding city. Continuing the book’s general penchant to view every development through the lens of Freemasonry,10 it argues that, in Nauvoo, the Prophet “began to move from a covert to a more overt Masonic model.”11 Regrettably, however, arguments that Joseph Smith was primarily following an “overt Masonic model” in his vision for Nauvoo are made without considering additional, significant crosscurrents discussed in other, broader histories of the Nauvoo period.12

Likewise, chapter 15, which provides a description of the “political kingdom of God,” strives to tie Joseph Smith’s inspiration for the Council of Fifty, the planned exodus to the West, and his candidacy for the United States presidency to his Masonic interests as a primary motive. Here, again, the argument would be more persuasive if additional perspectives on the dynamics at work in these councils had been included in the context of discussion and also evaluated for their merits.

Chapter 17 provides a summary of the death and burial of Joseph Smith. Commendably, it gives an excellent account of credible [Page 230]Masonic connections (e.g., the words Joseph uttered just before he fell to his death from a window of the Carthage jail). However, some of the claims (e.g., efforts to relate Masonic legends about the death of Hiram Abiff thematically to the history of Joseph Smith’s assassination) are pursed with less substantial evidence and arguments.

Largely breaking new ground, chapter 18 pulls together selected events relating to nineteenth-century Masonic and quasi-Masonic initiatives in Utah and within other branches of the Restoration that proliferated after the death of Joseph Smith. This chapter, pulling threads together from many scattered and little-known sources, is one of the most notable new research contributions of the book.

2. What’s Questionable

In chapters 2, 4–8, and 14, we encounter evidence and arguments that are typically more questionable than those provided in the largely historical sections of the book. I have grouped the themes from these chapters into three sections — the first exploring the question of the importance of Freemasonry in Joseph Smith’s early years, the second discussing Masonry and modern scripture, and the third dealing with temples and temple ordinances. Additional discussion of temple themes is found in part three of this review.

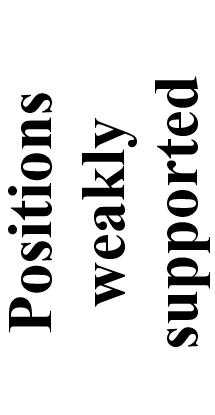

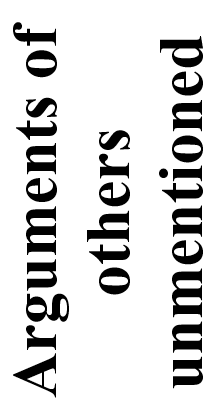

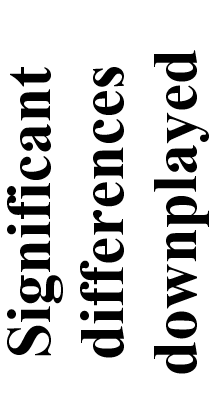

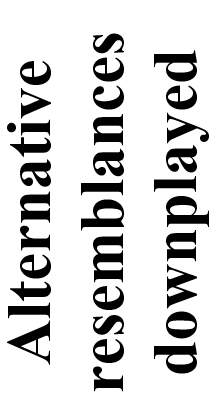

Table 1 summarizes selected examples that rely on the following faulty argumentation patterns that are repeated throughout the book. These include:

- Advancing positions that lack strong evidence. A straightforward example is when the book claims that in Cain’s announcement, “I am free” (Moses 5:33), he was “apparently alluding to the Free-Mason.”13 In such cases, the book merely asserts what, for the reader’s sake, ought to be supported by specific evidence. As another simple instance, the book states, without convincing argumentation, that “the Masonic Enoch legend as described by George Oliver seems a likely source for Mormon teachings surrounding Adam-ondi-Ahman.”14

- Failing to engage with previous scholarship on relevant subjects. For instance, the book advocates ideas originally proposed by John L. Brooke and Clyde R. Forsberg, Jr. that Joseph Smith’s translations and teachings early on in his ministry should be characterized as part of his effort to reform “spurious” Masonry.15 However, the book fails to grapple with criticisms of Brooke’s and Forsberg’s approaches raised previously by Latter-day [Page 231]Saint and non-Latter-day Saint scholars. Scholars can, of course, be forgiven for their initial impulse to avoid relying on the work of critical scholars who have themselves used weak and faulty argumentation, including sarcasm and ad hominem attacks, to advance their views. However, it is my opinion that no scholar can afford to ignore good arguments simply because of their source. This is true even when the authors of a given argument may not have deep expertise in Freemasonry. Indeed, what is wanting in most of the questionable arguments in Method Infinite is not more knowledge of Freemasonry — the book cannot generally be faulted in this regard — but rather better application of the principles of sound historical writing, comparative analysis, and in some cases (e.g., the Book of Abraham) specific knowledge from complementary fields of scholarship. In scholarly venues, good evidence and sound arguments for opposing views, regardless of their source, must be met with respectful responses so that the strengths and weaknesses of different views can be laid bare for all readers to see and evaluate for themselves.

- Implicitly overstating resemblances to purported Masonic sources of influence by omitting mention of significant differences. For example, the book describes some largely nonspecific similarities between Enoch’s gold plate in the Masonic Royal Arch rite and the golden plates of the Book of Mormon. Disappointingly, however, it omits any discussion of the substantial differences between these plates and the underlying stories of their discovery that have been described in previous publications.16 Discussion of both similarities and differences is needed to assess the strength of a given claim of correspondence.

- Ignoring pertinent, alternative correspondences outside of Freemasonry. For instance, the book cites Masonic parallels to Joseph’s kneeling and praying vocally prior to the First Vision but does not compare these gestures with general Christian prayer practices in Joseph Smith’s milieu. Before drawing the conclusion that the Prophet was acting more in the role of a proto-Mason than of a typical Christian, the relative strength of each of these competing hypotheses would need to be considered.

- [Page 232]Occasionally introducing idiosyncratic errors of other kinds. For example, on p. 164 the authors say they are citing Joseph Smith’s “diary” from July 14, 1835, when the text was actually composed at least eight years after the dated entry.17 As another example, the book mistakenly identifies a figure in Book of Abraham Facsimile 2 has having “his right arm … ‘raised to the square,’ surmounted by a pair of compasses”18 and incorrectly includes “square and compasses” and “penalties”19 as Masonic items that were included in Joseph Smith’s explanations of the facsimiles. Such errors should not be dismissed as simple differences of opinions but rather are the kinds of things that can be minimized through careful reading of primary sources and familiarity with current scholarship in the relevant disciplines.

Table 1. Selected Examples of Questionable Arguments

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joseph Smith’s Early Life (chs. 2, 4) | |||||

| Treasure-seeking and Royal Arch Masonry | ✓ | ||||

| The First Vision and Masonic ritual | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Modern Scripture (chs. 5–7) | |||||

| The Book of Mormon | |||||

| Spurious Masonry in Book of Mormon and life of JS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Plate of Enoch and golden plates of Book of Mormon | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Masonic themes and Book of Mormon translation | ✓ | ||||

| Masonry and Anti-Masonry in the Book of Mormon | ✓ | ||||

| The Book of Moses | |||||

| Creation from unorganized matter | ✓ | ||||

| Teachings of the angel to Adam and Eve | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Oaths and naming of Cain | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Book of Moses account of Enoch | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| The Doctrine and Covenants | |||||

| The Saints John | ✓ | ||||

| Keys | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| [Page 233]Degrees of glory | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Receiving the fulness | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| The “celestial lodge” | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Adam-ondi-Ahman | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Eternal matter | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Eternal bonds | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| The Book of Abraham | |||||

| Translation vs. “midrash” | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Priesthood authority | ✓ | ||||

| Spirits and intelligences | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| The divine council the Book of Abraham | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Book of Abraham Facsimiles and KEP | |||||

| History of the facsimiles | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Facsimile 1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Facsimile 2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Facsimile 3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Kirtland Egyptian Papers | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Temples (chs. 8, 14) | |||||

| Kirtland Period | |||||

| Overall Kirtland Temple design and supervision | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Kirtland Temple cornerstone laying | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Kirtland Temple pulpits | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Kirtland ritual greetings, washings, and anointings | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Hosanna shout | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Passing of the temple veils in Kirtland | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Nauvoo Period | |||||

| Sacred garments | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| High-priestly clothing | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Ritual ascent | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Quorum of the Anointed | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Nauvoo Temple architecture and furnishings | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

[Page 234]Chapters 2 and 4: How Important Was Freemasonry to Joseph Smith Early in His Life?

The general premise of chapter 2 is sound — namely that Joseph Smith’s first encounters with Freemasonry occurred long before he came to Nauvoo. Indeed, it may be said that the Prophet, like many Americans of his era, “grew up around Masonry. His older brother Hyrum … was a Mason in the 1820s,20 as were many of the Smiths’ neighbors. … To not be at least dimly aware of Masonry in western New York in the middle to late 1820s was impossible.”21

That said, exactly what Joseph Smith knew about the specifics of the rituals of Freemasonry and when he came to know these details is a debated question. A ready source of information about Masonry for the young Prophet would have been the exposés of the anti-Masonic movement, whose epicenter was not far from the Smith home. He undoubtedly talked with his friends and family about Masonic ideas and controversies — including the Morgan affair.22 Moreover, enlightenment ideals cherished by Freemasonry were certainly in the air. But the book does not support its claims that the Smith family’s early treasure-seeking practices and the First Vision were based on Freemasonry with convincing evidence.

Were the Smith family’s early treasure-seeking practices modeled on the rites of Royal Arch Masonry?

After a lengthy description of treasure-seeking, the book cites an 1875 newspaper article containing the statement that treasure-seeking might be seen by believers as “an allegory practically expressed of a searcher after truth.”23 From this single general assertion the book leaps to the claim that the “Smiths’ treasure seeking activities” were “similar to how they appear in Masonic ritual.”24

However, those who are familiar with the rites of Royal Arch Masonry will know that the most interesting details of the practices of New England treasure-seekers are not found in the ritual drama of the relevant Masonic legend. That is not to say that there is no connection between the magical practices of treasure-digging and Masonry broadly speaking — indeed, this relationship invokes a complex and important subject that deserves a more thorough and up-to-date treatment of its own. However, in my view, the book fails to make a strong case for its claim of a meaningful connection between the details of treasure-digging and the specifics of what is described in relevant Masonic ritual [Page 235]and legend. See more about the differences between the story of Enoch’s plate and the story of the Book of Mormon golden plates below.

Was the First Vision modeled on Masonic ritual?

Equally problematic are the books’ claims in chapter 4 that the First Vision was “a literal manifestation of the Masonic initiation ritual,”25 including “elements of the archetype that he used to share the experience [that] came from his exposure to Freemasonry.”26 For example, the book seeks to compare the general theme of “confusion and strife amongst the different denominations” experienced by the Prophet prior to his retiring to the grove in prayer to “Masonic allegory” that “similarly traces man’s initial spiritual darkness and subsequent search for illumination” as it is manifested in the Masonic practice of the “‘hoodwink’ of cloth or leather that is placed over the candidate’s eyes” in which “Freemasonry undertakes to remove … human unawareness of spiritual truth.”27 Here, as frequently elsewhere in the book, the parallels hold in only a very general way, while details specific to Masonry lack convincing correspondences across Joseph Smith’s varying accounts.

In the book’s repeated efforts to tie events of Joseph Smith’s life with Freemasonry in near cradle-to-grave extent, even the most mundane details of the First Vision account do not escape claims of Masonic influence. Of course, there is nothing wrong in itself with undertaking detailed examination of this sort. However, Occam’s razor is brazenly defied when specific Masonic influence is attributed to details that are more easily explained as coming from the Christian milieu in which Joseph Smith was raised. For example, “the detail that Smith knelt as he prayed”28 is compared to two references to kneeling prayer in Masonic ritual without mentioning the more likely inspiration for both the Masonic gesture and the Prophet’s personal experience being that kneeling in prayer has been a common practice for Christians since the time of Christ.29

Similarly, the book parallels the fact that the Masonic initiate may “make a personal oblation, either silently or vocally, as he prefers” with “Smith’s confession that his experience in the grove was the first time he had attempted to pray vocally.”30 No attempt is made to justify why the option of praying vocally is a distinctive feature of Masonry rather than merely a common element of Christian prayer practices in Joseph Smith’s time. It should be further observed that Masonic legend and ritual makes no effort to hide, and often explicitly cites, biblical precedents for its elements.

[Page 236]Joseph Smith’s understanding of the temple developed over decades. But it is almost as if he had a vision of the whole before him from the very beginning of his ministry. Indeed, Don Bradley has argued that the First Vision was Joseph Smith’s initiation as a seer and constituted a kind of heavenly endowment. Acknowledging that the earliest extant account of the First Vision does not appear to modern readers to be anything like an endowment experience, Bradley writes:

Smith’s vision looks like a typical conversion vision of Jesus (insofar as a Christophany can be typical — that is, it shares a common pattern) when the account from his most “Protestant” phase is used and is set only in the context of revivalism. Yet there is no reason to limit analysis only to that account and that context. All accounts, and not only the earliest, provide evidence for the character of the original experience. Indeed, literary scholars Neal Lambert and Richard Cracroft have argued from their comparison of the respectively constrained and free-flowing styles of the 1832 and 1838 accounts that the former attempts to contain the new wine of Smith’s theophany in an old wineskin of narrative convention.31 While the 1838 telling, in which the experience is both a conversion and a prophetic calling, is straightforward and natural, the 1832 account seems formal and forced, as if young Smith’s experience was ready to burst the old wineskin or had been shoehorned into a revivalistic conversion narrative five sizes too small.32

Noting that “latter-day revelation gives us the fuller account and meaning of what actually took place” on Mount Sinai when Moses experienced a heavenly ascent that took him into the presence of the Lord,33 Elder Alvin R. Dyer wrote that it was “similar to that which was experienced by Joseph Smith in the Sacred Grove.”34 Thus, one might more fruitfully compare Joseph Smith’s personal experiences with visions and revelations to the heavenly ascents of ancient prophets such as Enoch, Moses, Abraham, and the brother of Jared than to either nineteenth-century revivalist visions of God or the allegories of Masonic ritual.35

Chapters 5–7: Masonry and Modern Scripture

With respect to the relationship of Masonry and modern scripture, the book makes the following bold claim:

[Page 237]Because the building blocks of his work were typically Masonic beliefs that permeated his environment, Masonic-like expansions are found in every Mormon scripture from the Book of Mormon to Joseph Smith’s inspired revision of the Bible, and from the Doctrine and Covenants to the Book of Abraham. Numerous ideas from these works that Latter-day Saints have come to believe are uniquely Mormon have antecedents in popular Masonic sources of Smith’s day.36

Below, the discussion of examples drawn from the book demonstrates that this claim is overstated.

Suggestions of Masonic Themes in the Coming Forth of the Book of Mormon

The history of the Book of Mormon given in chapter 5 begins with common tropes relating to treasure-digging and magi cal practices. However, because the book does not explicitly connect these themes to Freemasonry, I will say no more about them here.

That said, the book does go on to advance the claim that the “accounts of the recovery of the golden plates are intimately connected with the backstory of the Royal Arch Degree.”37 Method Infinite characterizes the discovery of the Book of the Law38 described in the Bible and taken up in the legends and rites of Freemasonry as a “restoration of true religion,” purportedly making the story of the coming forth of the Book of Mormon “archetypally Masonic” and “a fulfillment of Masonic expectations.”39 In the following sections I discuss the strength of this claim.

To what extent can Joseph Smith’s life and translation of the Book of Mormon be seen as a fulfillment of Masonic expectations — in particular, as a reformation of “spurious” Masonry?

Before reaching chapter 5, the reader has already been introduced to the book’s argument that the Book of Mormon — and, indeed, all the key events in Joseph Smith’s life and teachings — are best understood through the lens of Masonry. Chapter 1 summarizes the ideas of Christian Freemasons such as William Hutchinson, George Oliver, and Salem Town that imaginatively posited a conflict between “authentic” and “spurious” Masonry that purportedly dated back to the time of the earliest Old Testament patriarchs.40

The argument that the primary impetus for Joseph Smith’s religious life was to reform “spurious” Masonry is arguably the predominant theme of the entire book. The roots of this idea date back at least to a 1994 [Page 238]volume by John L. Brooke.41 Unfortunately, Method Infinite makes no mention of the problematic aspects of Brooke’s arguments that have been raised by several Latter-day Saint and non-Latter-day Saint scholars.42 A similar argument to Brooke’s, positing that Oliver’s refashioning of G. S. Faber’s account of the origin of pagan idolatry made its way into the Book of Mormon, later appeared in the widely criticized 2004 book on Freemasonry among the Latter-day Saints by Clyde R. Forsberg, Jr.43

It is important to know that the arguments about the early relevance of Oliver’s “authentic” and “spurious” Masonry that were raised by Brooke, continued by Forsberg, and revived in Method Infinite are modern inventions that, so far as I am aware, are not backed by any nineteenth-century statements by Joseph Smith or anyone else. Though Joseph Smith was aware of Freemasonry from a young age and the establishment of the fraternity certainly became an important element of the Prophet’s plans in Nauvoo, the book does not provide compelling evidence from Joseph Smith’s early ministry (or later) that he presented himself as a “Masonic restorer.”44

Instead, his life and mission were invariably couched in sermons and scripture as a realization of the prophecies of biblical figures45 rather than as “a fulfillment of Masonic expectations.”46 The coming forth of the record of the Nephites was similarly envisioned as a confirmation of biblical prophecy.47 As to the purpose of the Book of Mormon, the climax of its preface explicitly informs us that it was written to convince “the Jew and Gentile that Jesus is the Christ, the Eternal God, manifesting himself to all nations.”

How similar are Masonic legends relating to the finding of the plate of Enoch to the discovery of the golden plates of the Book of Mormon?

Although the book describes some loose similarities, it offers no nineteenth-century evidence that Saints, skeptics, or Masons in Joseph Smith’s day saw noteworthy resemblances between the actual historical events of the coming forth of the Book of Mormon and the ritual-related legends of Freemasonry.

In addition, in making its claims, the book fails to cite scholars who have previously questioned the strength of supposed resemblances between the plate of Enoch (described in Masonic legends but not an explicit part of the Royal Arch degree at the time of Joseph Smith48) and the plates of the Book of Mormon. For example, William J. Hamblin, Daniel C. Peterson, and George L. Mitton have noted that49

[Page 239]the differences between the two stories are far greater than the alleged similarities: Enoch is not mentioned in the coming forth of the Book of Mormon. The main Enochian text is inscribed on a stone pillar50 [an idea that the Masons derived and elaborated from Jewish and early Christian traditions51], not on golden plates. The gold plate in the Enoch story was a single inscriptional plate, not a book; it was triangular rather than rectangular; and it contained the ineffable name of God, which plays no role in the Book of Mormon story.52 … Joseph’s golden plates were in a small stone box, while Enoch built a huge underground temple complex with “nine arches” and a huge “door of stone.”53 And whereas the Book of Mormon is composed of history and sermons, Enoch’s pillar contains “the principles of the liberal arts, particularly of masonry.”54

Are there Masonic parallels to the seer stones, spectacles, and the Urim and Thummim used in the translation of the Book of Mormon?

In relation to this question, the book points out that the Masons, like many Christians of their day who were attracted to esoteric themes, were interested in biblical and other accounts relating to such artifacts. The book then attempts to connect the literal key used to open the “ark of the covenant” in Masonic legend and the key for the cipher used to read Enoch’s gold plate by relying on a single mention by Joseph Smith that the spectacles or Urim and Thummim constituted a “key” by which he could both translate and also “ascertain the approach of danger either to himself or the record.”55 Any reader who could be persuaded that the slender thread of this remark might be adequate to suspend a heavier argument should also be reminded that there is nothing uniquely Masonic about the use of the term “key” in any of these usages.56

Claims that the Book of Mormon is a Masonic or Anti-Masonic “Bible.”

The question of whether the Book of Mormon is “Masonic” or “Anti-Masonic” has been a debated theme. Most scholars agree with Martin Harris, who called the Book of Mormon an “anti-masonick Bible.”57 By way of contrast, Method Infinite disputes “the common assumption that [Joseph] Smith drastically reversed his views of Masonry over time from being ‘anti-Masonic’ during the period of the [Book of Mormon] translation to fully adopting Masonry in the final years of his life.”58

[Page 240]Personally, I acknowledge the importance of the views of those who, at the time of the book’s publication, saw its potential influence for good or evil as a function of whether it was perceived as siding with or arguing against the Masons. However, the issue of Masonry in the Book of Mormon bears not only on how it was received by readers but also on how it was produced by Joseph Smith.

For instance, those who believe the Prophet was entirely bound to a character-by-character, word-by-word reproduction of the source text as described by David Whitmer,59 any suggestion that Masonic vocabulary made its way into the Book of Mormon contradicts the view of the book as an ancient work. However, what evidence exists seems consistent with Brant Gardner’s view that the English translation of the Book of Mormon more often than not exhibits functionalist rather than literalist equivalence with the original record. In other words, “unless a very specific, detailed textual analysis supports an argument that particular words or passages are either literalist or conceptual,” Gardner favors the idea that Joseph Smith’s translation “adheres to the organization and structures of the original [plate text] but is more flexible in the vocabulary.”60

Importantly, even in those instances where the Prophet’s Book of Mormon translation seems to have reproduced archaic literary features of the original plate text (which some scholars take as evidence that Joseph Smith was “reading” rather than composing his dictations61), the historical record suggests that ensuring a divinely adequate English expression of the Nephite source was an exhausting effort that is better described in terms of active, immersive spiritual engagement than as passive reception and recital.62 In that light, it may be significant that the Book of Mormon itself refers to the process of rendering a text from one language to another under divine direction — whatever the exact nature of that process ultimately turns out to be63 — more frequently as “interpretation” than as “translation.”64 As Kathleen Flake puts it, Joseph Smith did not see himself merely as “God’s stenographer. Rather, he was an interpreting reader, and God the confirming authority.”65

To sum up, even though I see the claims of direct influence of modern Freemasonry on its account as unlikely, the evidence of modern scholarship leads to the view that in Joseph Smith’s divinely inspired translation of the Book of Mormon, there is room for the introduction of vocabulary and phraseology that was not, strictly speaking, present on the gold plates.

[Page 241]In any event, my view is that believers in the antiquity of the Book of Mormon like Martin Harris as well as skeptics who see it as a modern production err — or at least overstate the case — when they characterize the book either as a pro-Masonic or anti-Masonic Bible. This is because, although there are some terms and themes scattered throughout the five-hundred pages or so of the Book of Mormon that can be easily imagined as relating in some way or another to Freemasonry, these ideas can hardly be thought of as the account’s predominant message.

Three items are frequently cited by proponents of Masonic influence in the Book of Mormon:

- The use of the term “secret combinations”

- Satan’s use of a flaxen cord to lead the wicked, and

- Lamb-skin aprons of the Gadianton robbers.

So much ink has been spilled on these three items already that I think I can add little to the discussion except to refer the reader to representative studies that reach conclusions different from the book.66 Disappointingly, Method Infinite does not mention previous research on these issues by other scholars, leaving the typical reader with the impression that the views and arguments presented in the book are unprecedented and unopposed.

Going further, however — to the credit of the authors — chapter 6 extends the discussions of Masonry in the Book of Mormon beyond the three common items to include more rarely explored topics. For example, it mentions Book of Mormon passages drawing on biblical and Jewish sources that refer to the exodus of the Israelites from Egypt, traditions about beheading and “smiths,” themes about lineage and language, the shining stones of the Jaredite barges,67 passing through the veil,68 bees,69 and the titles of “prophet, priest, and king.”70 However, when read in light of the important body of Latter-day Saint scholarship on these issues that goes unmentioned in the book,71 the discussion of these topics in Method Infinite actually strengthen arguments that the Book of Mormon is more strongly ancient and biblical than Masonic.

Proposed Allusions to Freemasonry in the Book of Moses

As evidence of Masonic influence, the authors cite Joseph Smith’s teachings about creation from unorganized matter, the teachings of the angel to Adam and Eve about animal sacrifice (Moses 5:6–7), the oaths and naming of Cain as “Master Mahan” (Moses 5:29–31, 49–51), and the Joseph Smith account of Enoch (Moses 6–7).

[Page 242]Creation from unorganized matter (Moses 2:1–2; Genesis 1:1–2; Abraham 4:1–2)

The book rightly observes that Masonic texts published in Joseph Smith’s era state that the earth was originally “without form or distinction” or that it went from “chaos to perfection.”72 However, these ideas are not specific to Masonry. Rather, they are common themes in scholarly exegesis of Genesis 1:2 based on the underlying Hebrew of “without form and void.”73 That said, what is more significant in Joseph Smith’s teachings are statements where he went beyond standard Bible commentaries of his day to argue that the word “created” should be rendered “formed, or organized”74 Though these additional teachings currently appear to be unknown in nineteenth-century Freemasonry, they resonate with contemporary Bible scholarship.75

Teachings of the angel to Adam and Eve (Moses 5:6–8)

The book correctly observes that “the idea that sacrificial animals were first introduced to Adam as a representation of the Lamb of God is in accordance with popular Bible commentaries of the time.”76 Hence, these teachings are not indicative of specific Masonic influence. However, research by Latter-day Saint scholar David Calabro goes further in indicating the ritual basis for Jewish and early Christian elaborations of stories of Adam and Eve.77 Unlike the few and brief mentions in the legends and rites of Freemasonry that focus more on the Fall than on the Redemption of Adam and Eve, the context of the Adam and Eve account given in the temple endowment bears strong resemblance to these early Christian precedents.

Oaths and naming of Cain as “Master Mahan” (Moses 5:29–31).

As to the oaths and self-imprecations of those who lived before the Flood mentioned by the authors, see, for example, the similar language in 1 Enoch,78 which the book rightly concludes “may have been available on the western frontier by 1830.”79 With much less warrant, however, the book goes on to claim that in Cain’s announcement, “I am free” (Moses 5:33), he was “apparently alluding to the Free-Mason.”80

With respect to the reference to “Master Mahan” in the Book of Moses (5:49), the book supposes that “Master Mahan” is a simple corruption of “Master Mason.” Commendably, the older work of Hugh Nibley81 and D. Michael Quinn82 are mentioned by the book as advocating ancient derivations of the term as a competing hypothesis.83 Regrettably, however, the authors did not also consult more recent work by scholars [Page 243]on this question.84 For example, as Stephen O. Smoot observes, there is a perfectly good Semitic etymology for “Mahan,” namely “Hebrew māḥâ (‘to wipe out, annihilate’), which would be thematically consistent with Cain’s declaration at Moses 5:31.”85 For that matter, a similar use is attested in Genesis 4:18 in the name Mehujael and in later appearances of a related verb in Genesis 6 and 7.86

Book of Moses account of Enoch (Moses 6:22–8:2)

The book examines possible nineteenth-century sources for the Enoch account in chapters 6 and 7 of Joseph Smith’s Book of Moses. While not dismissing the possibility that 1 Enoch was available to Joseph Smith, it correctly discounts the idea that Moses 6–7 was inspired by 1 Enoch,87 the only significant ancient Enoch account Joseph Smith could have known directly in his environment. Instead, it (incorrectly) argues — after having examined what it considers to be the “many similarities” between Moses 6–7, Freemasonry, and ancient sources — that “Smith’s Enoch most closely resembles that of the Masonic legend.”88

Elsewhere, I have published one of two brief and highly similar texts of the Masonic Enoch legend cited in Method Infinite so readers can compare it to the Book of Moses Enoch chapters for themselves.89 I have also described many ancient affinities to the ancient Enoch literature, in particular the significant Dead Sea Scrolls work entitled The Book of Giants.90 These additional, ancient sources, which Joseph Smith could not have known, closely parallel Joseph Smith’s Enoch account almost from start to finish.

By way of contrast, a reading of the Masonic Enoch legend will reveal that most of the resemblances to the Book of Moses Enoch — for example, the degeneracy of mankind, a call to preach, a gathering of prophets, a vision on a mountain, a divine transfiguration — are of a general nature, common to several Old Testament prophets. On the other hand, most of the unusual features of the Masonic story — for example, the recovery of the sacred name or word, the building of a subterranean temple, a golden triangle containing ineffable characters, the erecting of marble and brass pillars — are absent from Moses 6–7.

The Doctrine and Covenants

The book’s discussion of the Doctrine and Covenants confidently claims that many of its sections “included Masonically inspired midrash.” However, from the points discussed below readers will see that most of [Page 244]the examples given in the book have greater affinity to the Bible than to Masonry.

The Saints John (D&C 7; 84:27–28)

After a brief explanation of the importance of John the Baptist and John the Beloved in Freemasonry, the authors claim that “Joseph Smith’s writings show a familiarity with the Masonic veneration of the ‘Saints John.’”91 As evidence, they cite two Doctrine and Covenants passages: (1) the revelatory expansion of John 20:21–23 in section 7 describing the Apostle John’s mission to tarry on earth till Christ comes, and (2) the verses 27–28 of section 84 describing John the Baptist’s ordination to the lesser priesthood that was restored at the time of Joseph Smith. The authors conclude, without specific warrant or further argument, that “these two sections of the Doctrine of Covenants provide examples of Joseph Smith’s use of the Masonic concepts of a bifurcated Priesthood, restoration, and the Saints John in order to create a distinctive Mormon midrash.”92 However, the book does not identify anything distinctively Masonic in either of these revelations other than the names of “John,” and neither revelation provides evidence of any special joint “Masonic veneration” of the “Saints John” among the Latter-day Saints.

Keys (D&C 6:28; 7:7; 13:1; 27:5–6, 9, 12, 13; 28:7; 35:18, etc.)

The book tries to connect the visual symbol of the “key” in Masonry, signifying secrecy, to statements by Joseph Smith about secrecy — one of which explicitly refers to Freemasonry. But, despite the focus on the claim of Masonic influence in the Doctrine and Covenants in this section of the book, no specific scriptural references are given as examples of instances where the term “keys” refers to “secrets”93 rather than to priesthood authority — as in the well-known New Testament example of Matthew 16:18–19 and in Doctrine and Covenants verses that specifically equate keys to “authority.”94 In addition, even if examples from the Doctrine and Covenants equating “keys” to “secrets” had been provided in Method Infinite, it should be noted that none of the senses of the term “key” in Joseph Smith’s time and place is unique to Masonry.95

Degrees of Glory (D&C 76)

After describing section 76, which details the three kingdoms of glory, the book includes a paragraph from the Christian Mason George Oliver.96 Oliver cites biblical verses referring to the third heaven (2 Corinthians 12:2), differences in glory (1 Corinthians 15:41), and many mansions [Page 245](John 14:2). However, these New Testament passages were also well-known to other Christians in Joseph Smith’s day. The brief comment by Oliver from a Masonic work that follows adds little to the obvious general meaning of the verses and contains nothing that is specifically relevant to the highly detailed requirements and blessings described in section 76 itself.

Receiving the Fulness (D&C 93:12)

The book mentions D&C 93:12, which details how the fulness is not received all at once, but rather from “grace to grace.” As evidence that the revelation is influenced by Freemasonry, it summarizes a general concept found in some Masonic writings that “men are brought to the truth by receiving ‘light’ or knowledge progressively.”97 Of course, the idea of incremental acquisition of knowledge is neither novel nor unique to Freemasonry. Indeed, the expression of this idea in D&C 93:12 is more similar to a New Testament verse, John 1:16, that is not mentioned in the discussion within Method Infinite: “And of his fulness have all we received, and grace for grace.”

Celestial Lodge (D&C 93:22)

The book cites the Masonic term “celestial lodge” to describe the intimate fellowship of the faithful in heaven after death.98 While a loving community of a similar nature is envisioned by most Christians, the book does not demonstrate that the term “celestial lodge” is used in Latter-day Saint teachings or scripture. Lacking an exact equivalent of the term in the Doctrine and Covenants or anywhere else in modern scripture, the book attempts to equates the Masonic concept of a “celestial lodge” to D&C 93:22, which refers to “the church of the Firstborn.” Surprisingly, however, while arguing for Masonic influence on D&C 93:22 from the non-scriptural term “celestial lodge,” the book fails to consider the influence of the context surrounding the identical biblical phrase “church of the Firstborn” that appears in Hebrews 12:23.

Adam-ondi-Ahman (D&C 116)

The book correctly notes the historical and eschatological importance of the gathering of Adam’s posterity at Adam-ondi-Ahman as described in D&C 116. What it fails to do is to provide adequate justification for the conclusion that “the Masonic Enoch legend as described by George Oliver seems a likely source for Mormon teachings surrounding Adam-ondi-Ahman.”99

[Page 246]As in previous instances of claimed parallels of Masonic literature to Latter-day Saint scripture and ritual, there are more differences than similarities. In the Masonic legend, it is Enoch rather than Adam who initiates the gathering, the assembly is characterized as a “special assembly of Masons” in which Enoch presides rather than a calling together of Adam and Eve’s children in which Adam takes center stage, rather than focusing on an enumeration of the “enormous evils which were desolating the earth” in which Enoch “implored their advice and assistance in stemming the torrent of impiety which threatened an universal corruption,”100 the purpose of the gathering was to give Adam and Eve’s posterity a patriarchal blessing.101 Rather than culminating in a “terrible prophecy, that all mankind, except a few just persons” would die by water and fire (necessitating the building of Enoch’s legendary nine-arched temple),102 the gathering culminated in a moment of supernal glory when “the Lord appeared in their midst.”103 No mention is made in Masonic sources about a future eschatological reunion at Adam-ondi-Ahman.

Readers will find accounts that are more similar to the gathering of Adam and Eve’s children described by the Prophet in early Christian literature than they will discover in the Masonic tradition.104

Eternal Matter (D&C 130:22; 131:7)

The book cites William Hutchinson’s 1775 Masonic work stating that “matter … was eternal” in connection with Joseph Smith’s statement “the pure principles of element are principles which can never be destroyed.”105 It should be noted that a belief in these statements at this time was not unique to Masonry or Joseph Smith since the principles of conservation of mass had already been established by the eighteenth century. However, the book omits discussion of the more remarkable and original teaching of Joseph Smith that everything is matter.106 In other words, as Latter-day Saint astrophysicist Ron Hellings has written: “Whatever Joseph meant by ‘matter,’ it is clear he meant that nothing else exists.”107 Though the concept that “everything is matter” currently appears to be absent from the literature of nineteenth-century Freemasonry, it seems to resonate with modern inflationary cosmology.108

Eternal Bonds (D&C 128:18; 132:6–21)

The book compares a Masonic statement that speaks of science and knowledge that “link mankind together in the indissoluble chain of sincere affection” to the “welding link” available in Latter-day Saint priesthood ordinances. While both groups embodied the New Testament ideal of [Page 247]“brotherly love”109 and while Joseph Smith appreciated the emphasis of Masonry on certain “grand fundamental principles,110” it is assuming too much to explain the Latter-day Saint “doctrine of eternal union through the priesthood” as something that “evolved” from “Masonic principles.”111 It seems likely that most Christians of Joseph Smith’s day, including Christian Masons, would have ascribed the human yearning for peace on earth and continuing sociality in heaven as germinating in the basic tenets of Christianity rather than as a development that owed its genesis to Freemasonry

The Book of Abraham

Translation or imaginative “midrash”?

In chapter 7, the focus turns to the Book of Abraham. The chapter subtitle “Advancing the Interests of True Masonry” hearkens back to the book’s pervasive theme of Joseph Smith as “a Masonic restorer, bringing to light the heretofore concealed Masonic and priestly mysteries”112 in the Book of Abraham. As in previous applications of this theme to the work of Joseph Smith, the book provides no evidence that the Prophet or his contemporaries considered him to be “a Masonic restorer” as he took up the production of what perhaps became his most controversial book of modern scripture. Rather, he consistently claimed he was translating, or revealing, an ancient record from Abraham — and both Joseph Smith’s supporters and detractors took this self-characterization of what he understood the Book of Abraham to be at face value.

Commendably, the book cites multiple examples of the spectrum of opinions relating to the production of the Book of Abraham text,113 including the missing papyrus theory,114 the “mnemonic device” theory,115 and what is often called the “catalyst theory.”116 However, as is also evident in the book’s discussions of other works of modern scripture, the premise that the Book of Abraham “was influenced by nineteenth-century Freemasonry”117 contradicts the consensus of professionally trained Latter-day Saint Egyptologists who have concluded on the basis of extensive corroborative evidence that the Book of Abraham derives from authentic, ancient records.118 Disappointingly, the book fails to engage with the substantive body of research cited by these scholars. Instead, as will be further exemplified below, it simplistically asserts that Joseph Smith “selectively took [allegorical] Masonic stories or traditions” and transformed them “into literal or factual spiritual history.”119

[Page 248]In further support of the book’s premise that the Book of Abraham was a fully nineteenth-century development, readers are asked to accept the following statement: “Although some authors exult in pointing out the similarities of Mormon scripture, especially the Book of Abraham, with the ancient past, one must follow the chain of influence from the closest to the furthest out.”120 But why? If Joseph Smith was translating or revealing an actual ancient text from Abraham, then one must do nothing of the sort. On the contrary, if the Book of Abraham is what Joseph Smith professed it to be, then seeking nineteenth-century Masonic parallels and preferring those over ancient parallels is exactly methodologically backwards. This comment only makes sense if one already assumes the Book of Abraham is a modern text.

By means of a series of such assertions, the book ignores historical evidence that indicates Joseph Smith viewed his work as translation of an ancient record in favor of an unsupported and narrow view of the development of the Book of Mormon, the Book of Moses, and the Book of Abraham as a process of purely imaginative midrash undertaken in an attempt to “resolve problems” within “difficult passages of the Hebrew Bible.”121 Rather than uncritically adopting this older, more constricted view of scriptural expansion, readers should consult the more up-to-date views on “midrash” summarized by scholars such as Avram Shannon.122

The question of priesthood authority (Abraham 1:26)

With respect to the question of priesthood authority, the book merely asserts what it is attempting to prove: “Through this story [in Abraham 1:26], Smith reveals both his attitude toward the contemporary and spurious craft of Masonry and his reliance upon George Oliver’s ‘two traditions’ theory.”123 The book provides no evidence for this assertion other than the earlier claims that build on the discredited arguments of Brooke and Forsberg described above. Moreover, I see no hint in the Book of Abraham text or anything from Joseph Smith’s comments on the text that makes it obvious that Pharaoh’s imitation priesthood was thought to have anything to do with Freemasonry.

The book goes on to say: “Assuming that Smith’s midrash is meant to address the issue of Masonic authority, it warns that Freemasons may be righteous and good men, but at best, they can only imitate that ancient order that is the property of the holy priesthood.”124 Yes, if we assume a connection with Freemasonry, then we can somehow turn the Book of Abraham’s teachings about priesthood into a coded cipher about Masonry. But why should we make this assumption?

[Page 249]Spirits and intelligences (Abraham 3:22–23)

The book describes the Book of Abraham’s views on spirits and intelligences as “a tripartite theory of spirit creation. In this theory, intelligence exists in non-created form unorganized into a spirit being by God. The spirit can then inhabit a human body and become a mortal being.”125 However, there is no evidence that Joseph Smith ever taught this tripartite creation sequence.126 And it’s not obvious that the Book of Abraham teaches this either. “Spirits,” “souls,” and “intelligences” seem to be used synonymously in the Book of Abraham, unlike how these terms have sometimes been used by later Latter-day Saint writers. Likewise, a quick check of the 1828 Webster dictionary would have revealed that the book’s quotes from Masonic writer Will Hutchinson reflect the use of “intelligences” as a common way of speaking about “spiritual beings” rather than as a special notion reflecting specific Latter-day Saint teachings.127

The divine council (Abraham 3:22–28)

Pertaining to the book’s discussion of the Grand Council, Stephen O. Smoot,128 David E. Bokovoy,129 and Terryl L Givens,130 among others,131 have shown how the Book of Abraham’s depiction of the divine council fits perfectly in a biblical and ancient Near Eastern perspective. There is no need to resort to vague Masonic parallels. The ancient parallels are indisputable and, as mentioned in the book itself, the idea can be easily discerned in the Bible itself.132

Dating and Descriptions of the Facsimiles and the KEP

In this section, the book states that Joseph Smith’s journal entry for October 1, 1835, is “evidently”133 referring to the bound grammar (“Grammar and Alphabet of the Egyptian Language”). This assertion ignores John Gee’s well-reasoned arguments that in fact this entry is referring to the three documents Joseph, Phelps, and Cowdery worked on together called “Egyptian alphabet,” which is not the bound grammar.134 More generally, with respect to the descriptions and translations of the Joseph Smith papyri, the book cites Klaus Baer’s outdated 1968 translation of the Joseph Smith Papyri135 and does not mention Michael Rhodes’ or Robert Ritner’s better translations from the past decade.136

The section concludes with this statement: “Thus, the facsimiles’ connection of Abraham with the patriarchal priesthood and with a knowledge of astronomy persuasively derives from Freemasonry and [Page 250]substantially dates from 1835.”137 As seen above, the section offers only assertions, not carefully argued evidence, in support of both claims.

Facsimile 1

The authors attempt to make a connection between Facsimile 1 and Freemasonry by citing Masonic scholar George Oliver’s citation of a summary of ancient mysteries wherein the aspirant was required to

lay himself down upon the bed, which shadowed out the tomb or coffin of the Great Father. This process was equivalent to his entering into the infernal ship; and while stretched upon the holy couch, in imitation of his figurative deceased prototype, he was said to be wrapped in the deep sleep of death. His resurrection from the bed was his restoration to life, or his regeneration into a new world; and it was virtually the same as his return from Hades, or his emerging from the gloomy cavern, or his liberation from the womb of the ship-goddess.138

After citing a portion of this passage, the book comments as follows:

This could correspond to the scene Smith saw of Abraham on the sacrificial bed in Facsimile 1. The resulting Mormon midrash involved Abraham’s forced immolation on the lion couch by the idolatrous Priests of Pharoah. Hands raised in the grand hailing sign of a Master Mason, Abraham was raised from that bed and initiated into the higher mysteries.139

At first glance, what is most striking about this attempted parallel is the paucity of corresponding elements in the two accounts. Unlike Oliver’s initiate, the lion couch does not represent a tomb or coffin, there are no clues that Abraham is “wrapped in the deep sleep of death,” and his raising from the “bedstead” (Abraham 1:13) is portrayed in the Book of Abraham as a rescue from actual physical harm (Abraham 1:15) rather than as figurative episode in a ritual drama. Moreover, there are no clues in the Prophet’s explanation of the facsimile that hint at anything in a scene such as that described by Oliver. Instead, the explanation hews quite closely to what is shown in the papyrus itself.

Going further, there is a long-sustained tradition of Abraham’s near-sacrifice at the hands of his idolatrous kinsmen reaching back at least to the second or third century BCE.140 There’s no need to posit Masonic parallels. Second, neither the Book of Abraham nor Facsimile 1 say anything about “Abraham’s forced immolation on the lion couch.” Neither does the text or the facsimile describe immolation or the use of [Page 251]fire in the attempted sacrifice of Abraham. Third, in contrast to the conclusion in the book that the papyrus represents the grand hailing sign of a Master Mason, it seems more reasonable to suppose that the raised hand represents a well-known ancient gesture of prayer and supplication in the Bible and the ancient Near East with which Joseph Smith was no doubt already familiar from prayer traditions in his own day.141

Facsimile 2

In the book’s discussion of facsimile 2, an effort is again made to tie the Book of Abraham to George Oliver: “Just as George Oliver did in his Masonic writings, Smith pictured Abraham as the recipient of heavenly instruction concerning astronomy and mathematics.”142 But Oliver in turn lists Josephus as an informant for Abraham’s teaching of astronomy to the Egyptians,143 and ideas from the writings of Josephus may have been more widely known than Oliver’s in Joseph Smith’s day.144 Indeed, the authors commendably admit that “the writings of Josephus were available to the Latter-day Saints in 1835.”145

Going further, the book incorrectly states that “in Reuben Hedlock’s facsimile of the hypocephalus, a stylized figure of God on His throne appears to be giving a Masonic sign. His right arm is ‘raised to the square,’ surmounted by a pair of compasses; His other arm is extended at His side.”146 However, Latter-day Saint Egyptologist D. Michael Rhodes more correctly identifies this figure, consistent with the latest scholarship on the subject,147 as follows: “A seated, [probably148] ithyphallic god with a hawk’s tail, holding aloft a flail. This is a form of Min, the god of the regenerative, procreative forces of nature, perhaps combined with Horus, as the hawk’s tail would seem to indicate.”149 Rhodes continues:

Joseph Smith said this figure represented God sitting upon his throne revealing the grand key-words of the priesthood. Joseph also explained there was a representation of the sign of the Holy Ghost in the form of a dove. The Egyptians commonly portrayed the soul or spirit as a bird, so a bird is an appropriate symbol for the Holy Ghost.150

Facsimile 3

The authors assert, “Egyptologists have agreed that the image on Facsimile 3 represents the judgment of the dead before the throne of Osiris.”151 The authors find this important because of an Egyptian judgment scene that is integral to the thirty-first degree of Scottish Rite Masonry152 — though it should be noted that it’s unlikely that Joseph Smith would have known [Page 252]much if anything about this degree.153 Importantly, however, Quinten Barney has reviewed extensively how at a minimum it’s a presentation scene but may or may not be a judgment scene, since it is missing many elements needed for such an event.154

The authors again point out that the depiction of Abraham as delivering astronomy to the Egyptians “parallels Masonic tradition.”155 However, because the two pillars mentioned by Oliver Cowdery are mentioned in connection with Enoch, they are no doubt correct in concluding that the details attributed to Josephus in Cowdery’s account came “through Freemasonry.”156

It should be observed that in a list of terms known in Freemasonry that were included in the explanation of the facsimiles (though most were not part of the Book of Abraham itself), the book incorrectly includes “square and compasses” and “penalties.”157

The Kirtland Egyptian Papers

Much more might be said about the book’s discussion of the admittedly complex and difficult subject of the Kirtland Egyptian Papers than can be included in the present review. One of the major concerns with the section is that it takes several disputed points as matters of fact, including, but not limited to, an assertion concerning Joseph Smith’s supposed involvement with all aspects of the creation of these documents.158

Besides these major concerns, there are smaller but sometimes very consequential mistakes that reduce the trustworthiness of the analysis. For example, on p. 164 the authors say they are citing Joseph Smith’s “diary” from July 14, 1835, but then cite a portion of Joseph Smith’s manuscript history that was actually composed at least eight years after the dated entry.159

Chapters 8, 14: Temples

Kirtland Period

The introduction to chapter 8 begins by citing Nehemiah 4:17, where the Jews returning from exile worked with one hand holding a weapon. The book mentions that “Freemasons visually depict this scene with an emblem of the temple masons holding the implements of Masonry: a trowel and mortar in one hand, and a sword in the other for defense.”160 Wanting to connect this theme to the Book of Mormon, the book states that Nephi’s temple workmen built their temple “with tools of masonry in one hand and swords in another.”161 While it is true that 2 Nephi 5:14 [Page 253]does mention the sword of Laban in a general way, the allusive suggestion that the Book of Mormon account makes either literal or figurative mention to the “tools of masonry” has no basis in the scripture text. The passage is emblematic of much of the rest of the chapter: while biblical parallels to temples in the Kirtland and Missouri period are numerous, evidence of specific Masonic influence is frequently lacking.

The examples below are selective, not comprehensive.

Overall Kirtland Temple design and supervision

The book acknowledges that the Kirtland Temple was built according to instructions given to Joseph Smith and two others. Straining for similarities, it points out that in the symbolism of the legends of Freemasonry, “King Solomon’s Temple was built under the direction of three principals: Solomon, King of Israel; Hiram, King of Tyre; and Hiram Abiff, skillful artificer.”162 But that is as far as Freemasonry can take us. Though Joseph Smith’s role as head of the Church could be compared in a very loose sense to Solomon, there is little parallel in the roles or activities of his counselors to the two Hirams of Freemasonry. More importantly, in contrast to any hint from Masonic lore of a similar idea, the Kirtland Temple followed the governing precedent in the Bible and elsewhere in the ancient Near East that the design of temples is to come through revelation.163 Indeed, the Kirtland Temple was shown simultaneously to Joseph Smith and his counselors in the First Presidency in fulfillment of latter-day prophecy — “after the manner which I shall show three of you” (D&C 95:14) — in an open vision.164

With reference to the “Kirtland Temple’s counterpart in Missouri,” Matthew B. Brown notes the architectural description of those who witnessed the vision above. This description included:

an arched ceiling, Gothic doors and windows with Venetian blinds, a belfry, slip pews, choir seats, a fanlight, painted shingles, tiered pulpit stands or coves for the high (west) and lesser (east) priesthoods, curtains to divide the main chamber into four sections, and also veils to divide the pulpit stands into private areas.165 None of these features are considered to be a Masonic invention or a distinctive architectural style of speculative Masonry. A check of some of the popular architectural manuals of the day reveals that those manuals [Page 254]were the source of the decorative motifs associated with the Kirtland Temple — not the Freemasons.166

Kirtland Temple cornerstone laying

The book correctly points out that the first cornerstone of the Kirtland temple was laid at the southeast corner. It goes on to quote Masonic scholar Albert Mackey’s statement that the laying of the cornerstone in the east represents the dawn of a new day, “dissipating the clouds of intellectual darkness and error.”167 However, there is nothing exclusive to Freemasonry in the symbolism of the eastern sunrise — indeed, Mackey himself connects it to traditions of the ancient world. Moreover, while early eighteenth-century Masonic manuscripts locate the cornerstone of “Solomon’s Temple” in the southeast corner (consistent with the location of the cornerstone in the 1793 United States Capitol building168), sometime “in the period 1772–1829”169 Masonic tradition began to standardize the practice of laying the first stone at the northeast corner,170 a practice that continues to this day. While the authors state that the laying of the first stone of the Kirtland Temple “was an overt Masonic reference that followed the example set by Washington and his Masonic companions,”171 it should have also been noted that by the time the Kirtland Temple was constructed, laying the foundation at the southeast corner was no longer the most common practice in the rituals of Freemasonry.

Other “marked dissimilarities” between Latter-day Saint and Masonic cornerstone ceremonies are noted by Matthew B. Brown. In contrast to Latter-day Saints, Masons:

- Dedicate one stone rather than four stones

- Use corn, wine, and oil during their rite

- Use an architectural tool to “try the trueness of the cornerstone”

- Can carry out their ceremony with “only a handful of people participating” vs. “a large, set number of priesthood holders”172

Kirtland Temple pulpits

Elder Orson Pratt stated that the pattern for the Kirtland Temple priesthood pulpits, like others of the most important or unusual features of the building, were specifically revealed by God,173 serving both practical and pedagogical functions by their prominent grouping of quorum presidencies in hierarchical ascent.

[Page 255]In the book we are told that “this arrangement is related to the Royal Arch,”174 a rite of Freemasonry, yet there is nothing that closely links the formation or function of the pulpit to the gestures and “vaulted chamber containing nine arches”175 related to this rite except the number nine. We are also informed that the formation “emphasizes the sacred character of the number three, which suggests the presence of divine power”176 — plausibly true, but this is a common Christian conception, not something specific to Freemasonry. It is noted that the abbreviations for priesthood offices on each pulpit, which use “the first letter for each word,” each word followed by a period, is “widely employed throughout”177 Masonry. But, regrettably, the book does not inform the reader that “the concept of … formation” of such initialisms was “effortlessly understood (and evidently not novel)”178 to general readers of the 1830s.179

Matthew B. Brown lists additional divergences between the use of the pulpits and Masonic concepts and practices: