A review of David Charles Gore, The Voice of the People: Political Rhetoric in the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, Brigham Young University, 2019). 229 pp. $15.95 (paperback).

Abstract: David Gore’s book The Voice of the People: Political Rhetoric in the Book of Mormon is a welcome reading of Book of Mormon passages which engage in conversation with the biblical politeia — those parts of the Hebrew Bible that explore the constituent parts of the Israelite governance under judges and kings. Gore asserts that the Book of Mormon politeia in Mosiah is in allusive dialogue not just with the Bible but also the Jaredite experience of kingship in Ether. This allusive (intertextual) feature is present not just in the Book of Mormon but any text (Dead Sea Scrolls, New Testament, Apocrypha, Pseudepigrapha, and other writings) in the biblical tradition. The textual connection is conveyed when the biblical Noah is a type and King Noah the anti-type. The same is true of the biblical Gideon, who is a narrative bridge between the period of the judges and the transformation to monarchy; the Book of Mormon Gideon serves a similar typological function, bridging the reign of kings to the period of judges. Our modern notions of federalism and democracy owe much to the biblical legacy of covenant and republicanism, and although the Book of Mormon political structures share some features with modern federalism, the roots of both go deep into the Hebrew Bible. The Book of Mormon politeia, also a branch of that biblical political legacy, requires that readers understand that filiation, and demands awareness of the dialogue between the Book of Mormon and the Bible on the subject, so such reading can enrich our understanding of both Hebraic scriptures.

[Page 2]There is then creative reading as well as creative writing. When the mind is braced by labor and invention, the page of whatever book we read becomes luminous with manifold allusion. Every sentence is doubly significant, and the sense of our author is as broad as the world.1

—Ralph Waldo Emerson

Everything in the universe goes by indirection. There are no straight lines.2

—Ralph Waldo Emerson

I come not to bury directness but to praise allusion and indirection, to exhume metalepsis and invigorate intertextuality in the practice of reading both the Book of Mormon and the Bible. To this end David Gore’s The Voice of the People: Political Rhetoric in the Book of Mormon participates in a salutary trend toward close exegesis of the theological-political elements of the Book of Mormon text. Along with Jim Faulconer’s brief theological introduction to Mosiah3 (Mosiah is the most politically weighted portion of the Book of Mormon) we are now getting readers who can read out of the text the political reverberations in the book of Mosiah (and other parts of the scripture) which continue and amplify the theological-political portions of the Hebrew Bible. Both Faulconer and Gore suggest that the book of Mosiah requires being read against the backdrop of the biblical politeia, the primary productive contribution in Gore’s and Faulconer’s analyses.4

This trend of sensitive readers engaging the Book of Mormon with exegetical attention is a movement to be encouraged. The Mormon [Page 3]scripture itself insists that the Jewish and the Nephite scriptures must be read jointly, so it is praiseworthy to have readers engaging the texts, taking the text’s prior demand seriously that the Bible generally and Book of Mormon specifically be read for their rich intertextual layers. Nephi asserts in his tree of life discourse that the angelic guide said “these last records [the Nephite writings], which thou hast seen among the Gentiles, shall establish the truth of the first [the Hebrew and Christian scriptures], … wherefore they both shall be established in one” (1 Nephi 13:40, 41). Book of Mormon believers have a responsibility to read the two scriptures as unified in their prophetic and narrative designs; and Book of Mormon skeptics have a responsibility to analyze the scriptures’ prophetic and narrative claims with at least a modicum of depth and understanding.

I attempt four tasks in this book review: (1) write a review of Gore’s book so the reader understands its contents and import while occasionally disagreeing with Gore’s readings, (2) introduce the reader to the notion of intertextuality/allusion in Hebraic texts, which is an essential prerequisite to understanding the Bible and the Book of Mormon, (3) demonstrate how the book of Mosiah (and first few chapters of Alma) uses such allusion to connect to and elaborate on the biblical politeia (1 Samuel 8–12), the law of the king (Deuteronomy 17), and other relevant biblical passages, while building out the Hebrew Bible’s political theory (or perhaps theories), and (4) increase the reader’s appreciation of the complexity of Book of Mormon narrative and the principles by which it conveys its meaning.5 I’ll draw upon a fair amount of biblical criticism in order to articulate a biblical politics, but my reader should be aware that I am barely digging the well to the upper stratum of the biblical criticism aquifer; much work needs yet to be done among the Saints to make use of the gift of biblical criticism to learn more about the Bible and the Book of Mormon so that the well of living water extends to the depth of that aquifer and not just to the upper reaches. Both the biblical and Book of Mormon texts are more sophisticated than we treat them, and we need to train our reading habits to follow in sophistication so we can make that living water plain and accessible for readers. I recognize that those four strands I attempt here to intertwine into a rope capable [Page 4]of supporting my readings may be beyond my reach and capabilities, but I ask my reader’s indulgence as I venture, despite the sheerness of the cliff face and roughness of the trail ahead.

Mormon also asserts that the Book of Mormon and the Bible must be read jointly, except reversing the direction of knowledge and understanding between the Bible (that in the following passage) and the Book of Mormon (this) from the way we believers read (that is, we too often read biblical narrative as primary to understand — usually as a proof text — the Book of Mormon, neglecting to read the latter’s narrative for its illumination of biblical narrative): “For behold, this is written for the intent that ye may believe that; and if ye believe that ye will believe this also; and if ye believe this ye will know concerning your fathers, and also the marvelous works which were wrought by the power of God among them” (Mormon 7:9). Belief and comprehension of the Bible, Mormon asserts, is rounded out and elevated by belief and understanding of the Book of Mormon, and if we don’t grasp the ubiquitous intertextuality between the Book of Mormon and the Bible, we apprehend far too little of either sacred text. We modern readers must be taught to read anew with scriptures as our primer, to be as sophisticated in our reading as the biblical and Book of Mormon writers were in their writing.

Gore treats the book of Mosiah, the first few chapters of Alma, and chapter 6 of Ether as addressing the institution of kingship, bringing excellent insights and innovative readings of those passages. I have labeled Mosiah the Book of Mormon politeia in order to focus attention on the change in constitution narrated there as a political revolution from kingship to judgeship. The discussion of kingship in 1 Samuel 8–12 and 15–16 (and its companion text Deuteronomy 17:14–20) is frequently designated the biblical politeia because these chapters anticipate and narrate a political reversal of what happens in the Book of Mormon, as they show a shift from judgeship to kingship among the Israelites. Gore is right and insightful in reading the biblical politeia and the Book of Mormon politeia in dialogue with each other, and the message is a variation on the theme I have already articulated: God exhibits a sacred discontent with the works of fallen humanity’s hands, and our political and social arrangements and governmental constitutions are no different. God creates the cosmos and pronounces the work “very good” (Genesis 1:31); and in a fallen world when humans create societies and polities, some may be better than others for particular purposes. But God doesn’t say at the end of the foundation of the first city/civilization after the fall (Enoch, Genesis 4:17) and the first city after the flood (Babel, [Page 5]Genesis 11:1–4, 9) “I approve this message.” That is, God is content to approve the pottery made by divine hands; but when humans continue the divine work of creation (even in imitation), the deity doesn’t endorse or take credit for the work of such fallible potters as we are: as with pottery, so with politics. Samuel resists the Israelites’ demand for a king, but God reluctantly gives the people what they want, knowing the people would be better off with the status quo than to implement monarchy. As late as the classical prophets in the Hebrew Bible, Hosea asserts that “they have set up kings, but not by me” (Hosea 8:4); God and the prophets resist the endorsement as much as political candidates imply or state that God is on their side.

When the “first” of an event happens in the biblical record (the first man and woman, the first murder, the first city, the first sacrifice by Adam, the first entry into a new land, the first king), that founding event is paradigmatic for all that follow, a pattern for good or evil that illuminates subsequent history; St. Augustine recognized the firstness of things to portend what ensues. The violence of Cain against Abel and Romulus against Remus demonstrated the violence upon which all cultures were built. The founding murder showed, the Church Fathers thought, that violence is the necessary mode of operation for the city of man. Gore notes that

the tragedy of human politics is not merely that all political regimes and economic systems tend toward corruption but that the corruption to which they tend goes beyond the political and economic realms. Whether corrupted by bad leaders from the top down or from cultural strife, contention, and violence from the ground up, the result is the corruption of human hearts, individually and collectively. (p. 12)

Gore astutely takes up the following material in the Book of Mormon in the following chapters.

Chapter 1: The Calling of Samuel and Mosiah: Mosiah’s Succession Crisis. Rightly, Gore reads the material in Mosiah 29 as an intertextual commentary on David’s calling and anointing in 1 Samuel 16, but more generally the chapter alludes to the transition from judges to kings in Judges and 1 Samuel (p. 33). Gore, in providing fresh insights to the discussion of political systems in the Book of Mormon, connects those passages to the institution of kingship among the Jaredites in Ether 6:19–27. By alluding to the Hebrew Bible’s political concerns, the Book of Mormon highlights wisdom and obtuseness in the biblical text’s characters: “The openness of the Book of Mormon to the Bible means [Page 6]not only that we can bring the two works into fruitful conversation with each other, but also that it is difficult to predict where the conversation will lead” (p. 31). This relationship between the two scriptural works isn’t one of “enthrallment” or “subservience,” as weak underreaders often assert, but instead shows how the Nephite scripture “reinforces the Bible’s relevance while at the same time refusing to accept what the Bible says as the last word about what the Bible means” (p. 30). Gore ably notes the correspondences between the biblical and Book of Mormon politeias and draws out keen insights in the allusive comparisons.

Chapter 2: Monarchical Succession in the Book of Ether. Gore notes the internal repetitions between the offer of kingship to Mosiah2’s sons and the sons of Jared and his brother in Ether. Pointing to what I have here labeled allusion or intertextuality, Gore notes that “the Book of Mormon is engaging in serious dialogue with the Bible, showing that the biblical stories are by no means finished or complete” (p. 61). Gore not only shows the narrative similarities between the two stories about dynastic kingship but, more importantly, provides a plausible reason why they are connected. Just before initiating a structural transformation from kingship to judgeship, Mosiah2 had translated the Jaredite record, so the lessons from endorsing kingship were conspicuous not just from the Nephites’ own experience with King Noah but also fortified from the Jaredite example. “By bringing Mosiah 29 into dialogue with the book of Ether and Judges-Samuel, Mormon draws attention to the weight of the phrase ‘the voice of the people’ to emphasize the responsibility of the people to express their desires and to bear the burdens — whether of kingly oppression or the shared responsibility of governing” (p. 62). Gore doesn’t often misfire in reading the relevant texts, but he does here. He cites Mosiah 25:12 to the effect that after the reunification of the three branches of Nephites (King Mosiah2’s Nephites and Mulekites, Alma1’s group of Zeniffites, and Limhi’s Zeniffite company), each group telling their story, “The people emerged from this assembly with a desire for greater unity. They no longer wanted to be recognized by their separate political identities because they ‘were displeased with the conduct of their fathers’ (25:12)” (pp. 71–72). But this action refers not to the Nephite assembly as a whole, or even the Limhi portion of it. It was the much narrower group — specifically the children of the priests of Noah — who were displeased with their fathers. These fathers had abandoned their wives and children to take wives of kidnapped Lamanite girls, and were absorbed into the Lamanite tradition. It was the much narrower group of Nephites who wanted no such patrimony, but preferred only to be known as Nephites. This fits with Gore’s theme of unity, for after [Page 7]this group disavowed their birth fathers and became Nephites, “all the people of Zarahemla were numbered with the Nephites” (Mosiah 25:13).

Chapter 3: Mosiah’s New Constitution. Gore notes that King Mosiah2’s pitch to convert the Nephite governing structure from kingship to judgeship is “based on quasi-democratic principles” but was fragile from its inception, although it lasted for nearly 1,200 years (p. 99) (with a period of tribal interregnum around the meridian of time). No apology should be made for referring to the system as democratic (that may not look like republican, presidential, or parliamentary democracy as we know it today; see p. 117), for democracy broadly defined is neither a modern nor an Athenian invention (as I will demonstrate in this review). The Nephite experience with bad monarchy (King Noah) prompts Mosiah2 to urge constitutional change. Mosiah2 midwifes change toward a more egalitarian system. But the reader must understand that equality means something different to Mosiah2 than the way we define the word today. For the Book of Mormon the emphasis isn’t on equivalence of rights or results but on equivalence of duty, each person carrying the burden of governance and civic obligation rather than a king (righteous or unrighteous) shouldering a larger share of the burden. “Mosiah saw inequality as one of the greatest harms to the people, and, as indicated above, he is no longer convinced that the sins of the people should be answered on the heads of their leaders” (p. 120). This equality means, additionally, that each person should labor to provide for him or herself and family (p. 121). I would add that each person should not live off public taxation or contribution, for such is priestcraft or kingcraft.

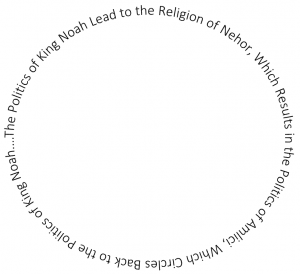

Chapter 4: Nehor Exploits Equality. As soon as Mosiah2 persuades the people to adopt judgeship and enact democratic — as opposed to dynastic — leadership, the system faces a challenge of legitimacy. Nehor emerges, stress-testing the commitment to equality, the basis of the new judgeship polity. Gore provides a summary of Emmanuel Levinas’s notions of ethical systems and applies them not just to the Nephite experience but to all human praxis. Mosiah2’s notion of equality is founded on the commitment to being-with-and-for-others, while Nehor’s proposed alternative ethic is founded on being-in-and-for-oneself (p. 134); and a second principle that each person should labor for her or his own support rather than being supported by the people. This may just be a philosophical restatement of the dialectic of selfishness versus selflessness, but Gore’s articulation is useful. The order of Nehor will be a long-lasting obstacle to Nephite cohesion and the government by judges: “The order of Nehor is an order of opposition rooted in [Page 8]being-in-and-for-oneself, and it lasts throughout the rest of the reign of the judges as a counterpoint to the regime established by Mosiah” (p. 135). Gideon is the narrative bridge between kingship and judgeship narratives. When Nehor is challenged by an aged Gideon, Nehor kills the sage. But remember that this same Gideon led a rebellion against King Noah’s misrule, and Nehor’s doctrine is just a systematic articulation of King Noah’s governing ethos. Gore notes the story’s intertextual character when he points out that this Gideon is intended to remind us of the biblical Gideon in the book of Judges, the charismatic leader who led the Israelites out of bondage to the Midianites. Both were charismatic military leaders from the tribe of Manasseh who emerged in a time of crisis to free the people from bondage. “One quite obvious clue that the book of Mosiah is open to and seeks to engage the biblical book of Judges is the presence of a character named Gideon” (p. 144). The Book of Mormon Gideon challenges wicked King Noah, while the biblical Gideon declines the Israelite offer of kingship. I will engage the two Gideons and Gore’s discussion of them, but I postpone until I leave behind my summary stage for an analytical one; I don’t think Gore gets the allusive comparisons quite right. After being tried and convicted of murdering Gideon, Nehor is executed, but his doctrine outlives him:

The order of the Nehors is a theological-political faction opposed to the work of Kings Mosiah1, Benjamin, and Mosiah, as well as both Alma1 and Alma the Younger, after his conversion, and during his time as high priest and chief judge. The doctrine of Nehor disrupts the possibility of establishing a regime of equality and the sharing of public burdens by sowing the seeds of inequality and idolatry. (p. 154)

The doctrine of Nehor also intensifies the rivalry between Nephites and Lamanites.

Chapter 5: Amlici’s Rebellion and a Heap of Bones. The theme chronicling the transition from kingship to judgeship continues in Alma 2 because verse 1 of that chapter ensures that the reader gets the connection by stating that Amlici is of the order of Nehor. Leading the Nehor dissidents, Amlici attempts to overthrow the new constitution, which prompts a referendum to revert to monarchy (with no intermedial Electoral College the “king-men” might use to manipulate and overthrow the will of the people expressed in an election). Amlici intensifies his attempt to negate constitutional governance through an attempted coup d’état. Led by Alma2, the narrative circles back to kingship. After the first day of battle between what the book of Alma will later call king-men [Page 9]and freemen (Amlici’s name has that Hebrew root for king — m-l-k — as do other Book of Mormon would-be or sometime kings such as Amalickiah) in the Nephites’ camp in the valley of Gideon. “As if it was not already obvious, the name of the valley where the battle breaks out is emphasized to show that Alma is defending the same cause for which Gideon opposed Nehor” (p. 179), and King Noah, by the way.

Conclusion: Awake to Mournfulness. While Gore recognizes the need for people of good will to be involved in politics, he rightly notes that we ought to recognize the limits of any political philosophy. “Politics is tragic to the extent that we exercise faith in political solutions to what are in reality religious problems” (p. 192). If we elevate the stakes of politics to a win-at-any-cost competition, then we haven’t understood the Book of Mormon’s take, which “depicts a politics of tragedy by showing us the worst that can happen when we take the stakes of politics too seriously” (p. 193). The consequences of sin can be ameliorated and souls converted, but not by political parties, and one ought not to treat soulless parties or factions as we do religious congregations. Nor should we consider congregations as extensions of political parties. “Politics cannot save us because of its fundamentally tragic character of overpromising on solutions to problems it cannot comprehend” (p. 193).

Gore’s reading accurately puts the Book of Mormon politeia (largely the book of Mosiah and the first few chapters of Alma) in persistent dialogue with the biblical politeia (1 Samuel and Judges, and more generally the entire Deuteronomistic History [Joshua-2 Kings with Deuteronomy also thrown into the description by some]); and such an effort ought to be rewarded with a wide readership. Josephus was the first writer in the Jewish and Hellenistic tradition not only to refer to the biblical politeia (a politeia is an analysis of the governing order in a society and its relationship to the governed; it is often translated constitution, and that is the way Josephus meant it); but also to argue that the Mosaic constitution was on par with those governmental structures analyzed by Aristotle and the broader Greek and Roman tradition. Gore provides keen and subtle insight both into the relationship between the two politeias but also into reading the Book of Mormon on its own.

The Ends and Means of a Scriptural Politics

In our fallen world — so far from God, so near to partisan politics — we humans fashion a matching lone and dreary political philosophy. Never should we make the mistake of asserting that our personal, party, or national politics are also God’s. That doesn’t mean that all politics [Page 10]are equally good or bad, just that we have to work through all political platforms while attempting to exorcise the evil and cruel elements and bolstering the good and moral; the moral and religious principles can be enacted in various ways by differing platforms. Like all aspects of the post-lapsarian world, the tares are yet interwoven with the wheat (in the primordial garden, apparently, weeds did not exist). Gore notes that “the larger narrative arc of the Book of Mormon is a critique not just of those in power, but of power itself” (p. 12). Most of us live compartmentalized lives in which our involvement in matters political aren’t sufficiently informed by matters religious. We feel good — perhaps even morally superior — in inventing or repeating lies we know are false in order to gain political advantage, insisting on supremacist notions regarding our own tribe or ethnic group, using our access to the levers of power to advance our private interests while declaring them to be in the public interest, or demonizing those who disagree with us as unpatriotic or ungodly while our own commitments resemble a highly selective patriotism.

The God of the Bible and the Book of Mormon is neither Republican nor Democratic (nor conservative nor liberal), and the Christ of the testaments advances a politics, but not one of this world. Gore notes that “sometimes we are tempted to use scripture to justify a partisan position or moralize against the opposing position” (p. 8). I am attempting to walk a fine line here: I agree with Gore, if I don’t misrepresent his position, that God is not a partisan when it comes to human politics, but we still must be able to criticize political positions based on their human qualities from within our own commitments, which include religious principles and practices. The scripture warns that political parties, political individuals, economic advocates, and economic positions are liable to deception and corruption. Citizens should trust but verify, and not even trust too much, for “whether corrupted by bad leaders from the top down or from cultural strife, contention, and violence from the ground up, the result is the corruption of human hearts, individually and collectively” (p. 12). The tendency to become partisans or advocates of parties or positions tends to make people forget the purpose of both big and small pictures: service to others. The institutions humans build are fallible and fallen, prone to error and cruelty, and we ought to improve beyond the limits of what politics can do, supplementing with moral and religious action.

A major divide between political opponents is over fundamental commitments toward individuals and social groups: should the [Page 11]happiness and fulfillment of the individual take priority over the good of social groups the individual inhabits, such as families, neighborhoods, nations, employers, religious congregations, and others? We would be more generous and charitable toward those who disagree with us if we recognize that major divide between those whose basic orientation is to empower individuals to self-actualize their possibilities, and those who elevate dedication to family, religious congregation, and other social units over individualism (or more likely, that sometimes the same person might favor individualistic commitments, and other times prioritize communal obligations, because our practice and principles need to be worked out in the mangle of life experienced through improvisation).

Gore refers to Levinas, a Jewish philosopher, whose philosophy takes seriously the obligation to tend to the other, which position is opposed to the worldly tendency symbolized by Cain, the founder of the first city in human history, according to the Bible, to be “in-and for-oneself.” Cain thought the answer to his question “am I my brother’s keeper?” was so obvious that even God should know it. The Bible portrays Cain not only as the first murderer but important as the founder of all civilizations, because all originate in violence, as Cain’s city did. God curses Cain to be a vagabond, but immediately after the cursing (Genesis 4:15), he goes out and establishes the first urban center (Genesis 4:17). The Cain syndrome of being-in-and-for-oneself is opposed to being-with-and-for-others, a true dichotomy of the two basic orientations people can embrace toward social life (p. 13). Like the Bible, “the Book of Mormon reiterates the biblical call to being-for-others, which is a radical politics acknowledging one’s own temptations toward freedom from responsibility as well as welcoming all the trials, troubles, and travails associated with bearing the burdens of the community (see Mosiah 29:33)” (p. 13). Politics tends to lose sight of being-for-others in favor of being-for-oneself or being-for-party, being-for-nation, being-for-my-ideology, being-for-people-who-look-like-me, or many more possibilities. The Book of Mormon conveys the biblical message that the problems we encounter in society are not fundamentally political problems but religious ones (p. 16). Therefore the solutions are necessarily religious, not political.

The Nephite scripture urges a “politics oriented toward the Other” (p. 3), one beyond bad and evil that cultivates self-interest and self-gratification. “In the here and now, politics rests on competition, conflict, and violence arising from self-assertion, anger, faction, vanity, and pride. Such politics traffics in a light-minded, pretentiously grave [Page 12]posturing that all too seriously reckons that the defeat of one’s opposition is all that matters” (p. 3). A politics of the Other requires that we recognize that those who disagree with us are more than likely rational, with good motivations, but perhaps moved by a conviction to purposes or ends that are different from those to which we are committed. The fact that our opponents’ political means and ends differ from ours doesn’t make them villains. Whether our political commitments emerge from highlighting individualism or communitarianism, our religious commitments ought to require that we reject the politics of cruelty. We should all agree that such policies, regardless of party affiliation, are odious and morally and religiously repugnant.

The Bible and the Book of Mormon call us to an ethics of love, of brotherhood and sisterhood, of inclusiveness and care. The better we read those scriptures, the better and more apt we are to enlarge our circles of love and acceptance. In the past 40 years, developments in our ability to read the biblical text have dramatically improved our capacity to understand the biblical and Book of Mormon text and context, and I will make use of some of that biblical criticism in this review. Such developments permit us to read between the texts to understand how Hebraic writings such as the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament, and the Book of Mormon are constantly in dialogue with each other to produce commentary on the world of politics that a single scriptural work cannot deliver, reflected through its limited prisms on reality.

Over the past four decades biblical critics have made huge advances in demonstrating that the Hebrew and Christian Bibles constantly allude to other portions of the scripture. We have come to the realization that intertextuality is a central feature of biblical textuality.6 Such persistent allusion is just as fundamental to Book of Mormon textuality as it is to any group in antiquity who believed they were still carrying out the biblical [Page 13]mandate to multiply and fill the earth and to make the blessings of the Abrahamic covenant available to all the progeny of Noah and Adam and Eve. If the reader doesn’t grasp the Book of Mormon’s constant allusion to the Bible, that reader doesn’t understand the Book of Mormon (or the Bible, for that matter, for as I have quoted Nephi already, “wherefore they both shall be established in one; for there is one God and one Shepherd over all the earth” (1 Nephi 13:41).

Allusive Scriptures and Metalepsis

Not only does the Hebrew Bible constantly and insistently allude to other parts of its own canon, but so do any subsidiary texts that followed in the biblical tradition: the Apocrypha, the Pseudepigrapha, the New Testament, the Book of Mormon, the Dead Sea Scrolls. These belated ramifying texts were in constant dialogue with the trunk but also the other branches. What Schiffman says about the Dead Sea Scrolls should also be applied to the Book of Mormon (and the other mentioned texts): “We have to acknowledge that, to a great extent, the authors of some of the scrolls saw themselves as in some way continuing the biblical tradition or actually living in a sort of time-warped biblical Israel.”7 Such persistent allusiveness, both internal to the Hebrew Bible and between successor writings and that Bible, places demands on the readers of the successor and ancestor writings. “Therefore, between this corpus and the Hebrew Bible — as well as inside the corpus — we should expect complex levels of intertextuality. Put simply, the Bible was formative for Second Temple literature and, hence, intertextuality was rampant.”8 A pressing need for readers to match the sophistication and complexity of the Bible and the Book of Mormon has come with the recognition of biblical intertextuality.

I ought to emphasize that in this persistent allusiveness — the New Testament, the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Book of Mormon and the rest of the family of ancient Hebraic writings (the descendent texts) — are merely doing what the predecessor text does. Biblical scholars and disciples have become manifestly more sensitive to this constant reference to earlier biblical passages and narratives, keenly aware that

the biblical authors themselves also comment on, explain, revise, argue with, and allude to texts written by their [Page 14]predecessors. The implications of this phenomenon, which we may call inner-biblical allusion and exegesis, are important both for students of the Hebrew Bible and for students of the religious and literary traditions that grew from it.9

Of course, any adequate understanding of the Bible requires that modern readers understand the ways moderns, medieval people, and ancients approached the texts with fundamentally different presuppositions.10 Any adequate grasp of the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament, and the Book of Mormon requires readers who have struggled to understand the persistent allusiveness of those scriptural texts. The writers paid the price to understand traditional modes and conventions, and contemporary readers must pony up in the same coin.

Ancient Hebraic writers used techniques we call allusive because they believed that God was in charge of history and God’s path keeps circling upon itself, so there are multiple falls from paradise, exodus escapes, redemptions from bondage, confrontations between kings and prophets, new covenants between God and humans, etc. The stories repeat patterns because history is repetitive. So too is human nature unchangeable (outside divine intervention), and like God’s salvation history, one eternal round, so it would be surprising if past events didn’t repeat, because human shortcomings are as predictable as sunrise, winter, or greed. For exploration of the political-theological nexus of Hebraic writings we must recognize that the children of Israel repeatedly were dominated by foreign despots and cultivated their own autochthonous tyrants. Consequently, we would expect to find political structures and other human inventions repetitive; King Noah of the Book of Mormon is not sui generis nor even original, but part of a pattern as old as humanity and human society itself.

Indeed, the self-aware manner in which Qumran sectarians and other Second Temple period authors reworked and drew on biblical ideas and biblical phraseology raises one final question: Is it possible that intertextuality is simply a complex word for phenomena that were just second nature to ancient [Page 15]Jewish authors? Perhaps “there is nothing new under the sun” (Eccles. 1:9).11

The problem for us moderns is that we don’t write or read the way ancient Hebraic writers wrote and read, nor do we think the way ancients thought. Consequently, we often miss too easily and too simply the point of ancient Hebraic narrative by assimilating antiquity to modernity.

I could point to the traditional analysis of allusion in Hebraic texts as typology in the Christian tradition, or I could take up Robert Alter’s notion of type scenes and related allusive techniques internal to the Hebrew Bible. I could rely on the more general discussion of intertextuality, which usually emerges from literary criticism; these are different approaches to describing the same phenomena. I will instead begin from New Testament scholar Richard B. Hays on metalepsis as the New Testament incorporates references to the Old Testament. Just as the Book of Mormon constantly alludes to the Old Testament, the New Testament also projects the history of salvation as one riff after another on Old Testament events and themes, because those Christian writers believed that their historical situation was an extension of that portrayed in the Old Testament. Hays narrows his focus to one type of allusive reference — metalepsis: one detail in the referring text can evoke a much larger narrative context full of detail in the alluding text while assuming the reader will understand. Metalepsis can be subtle, so elusive that it might easily be missed or misunderstood:

Allusive echo functions to suggest to the reader that text B should be understood in light of a broad interplay with text A, encompassing aspects of A beyond those explicitly echoed. This sort of metaleptic figuration is the antithesis of the metaphysical conceit, in which the poet’s imagination seizes a metaphor and explicitly wrings out of it all manner of unforeseeable significations. Metalepsis, by contrast, places the reader within a field of whispered or unstated correspondences.12

The invocation works from a mode of indirection. Metalepsis as a literary figure is extremely efficient, for “allusions are often most powerful when [Page 16]least explicit. This remains true even if some readers are slow of heart to discern the metalepsis.”13

For example, the gospels often invoke entire narratives from the Old Testament by dropping just one word or a name. In the gospel of Mark, the author is an expert at metalepsis by using such allusive details to see a much larger narrative world. “Significant elements of the intertextual relations lie just under the surface, suggested but not explained by the narrative”14 in which the reader of the metalepsis has some heavy lifting to do to keep up with the text. “The result is that the interpretation of a metalepsis requires the reader to recover unstated or suppressed correspondences between the two texts.”15 Much like Mark, Paul is constantly quoting, alluding to, echoing, and citing scripture. “The extraordinary thing about Paul’s use of this metaphor [comparing the incestuous relationship in the Corinthian congregation to the purification of the of the Passover dough] is how little he explains.”16 He leaves it up to the reader to catch the reference and fill out the connection. The auditor who misses the clue isn’t Paul’s ideal reader.

The gospels, like the Book of Mormon, persistently use various forms of allusion. Metalepsis is one such reference in which a small metonymic detail evokes a much larger and fuller narrative.

Metalepsis is a literary technique of citing or echoing a small bit of precursor text in such a way that the reader can grasp the significance of the echo only by recalling or recovering the original context from which the fragmentary echo came and then reading the two texts in dialogical juxtaposition. The figurative effect of such an intertextual linkage lies in the unstated or suppressed points of correspondence between the two texts.17

Modern readers commonly read the wrong meaning into scripture when scriptural narrative repeats with a difference. We moderns often mistakenly think in terms of copying, plagiarism, or lack of originality when we encounter a repetition, but these are all modern concerns, not ancient ones, and what modern readers often mistake as a deficiency [Page 17]should more likely be read as a plenitude. Biblical writers considered recurrences of foundational events more real (not mere facsimiles) because they repeated earlier patterns and paradigms. So attention to even the smallest allusive connection is essential to the reading enterprise: “the allusive ripples spread out widely from brief explicit citations to evoke larger narrative patterns.”18 The reader who is forewarned to look for quotations, allusions, and echoes is forearmed about the vigor needed to keep pace with the text.

The Book of Mormon’s use of a biblical name (Noah and Gideon are examples I will explore along with a single word — disguise — to ground my discussion of metalepsis) is able to recall to the reader’s mind the entire biblical backdrop of the drama from the Primeval History of Genesis, the period of judges and conquest, and the biblical engagement with monarchy. The gospels, like the Book of Mormon, persistently use various forms of allusion. Metalepsis is a minimal reference in which a narrative element evokes a maximal narrative context. We moderns (and historical criticism of the Bible exponentially compounds the tendency) are trained to think atomistically, to break the object of study into smaller and smaller units in the hope that when we get as miniature as possible we can reassemble the tree, the zebra, and the liver from those quarks and other subatomic particles. We ought to think of metalepsis as more like microcosmic thinking than atomistic study, in which the microcosmic object always connects up the chain of being to the macrocosmic original. Of course, to use the short phrase “chain of being” ought to remind the reader of more holistic medieval and antique thought when some unifying force (say, a deity) held nature together much as on a different scale gravity, electromagnetism, the weak nuclear force, and the strong nuclear force serve a similar function today.

For example, in the conflict between the prophet Abinadi and King Noah, one small clue points allusively to the many stories in the Old Testament with narratives of conflict between kings and prophets: the disguise Abinadi wears. Abinadi is to be seen in continuity with the biblical prophets: Abinadi comes in disguise (Mosiah 12:1); Saul comes in disguise to the witch of Endor to raise the ghost of Samuel (1 Samuel 28); a prophet disguises himself to condemn the king (Ahab) who released an enemy king (1 Kings 20:38); a prophet urges a naïve King Jehoshaphat to disguise himself in battle (1 Kings 22:30); King Josiah [Page 18]disguises himself to go to battle (2 Chronicles 35:22); and King Jeroboam tells his wife to disguise herself to consult the blind prophet Ahijah (1 Kings 14:2). The metalepsis occurs when with one small detail (the prophetic or antagonistic disguise) evokes the entire world of biblical stories about conflict between kings and prophets19 and the theological point bolstered by that series of biblical stories. Each narrative differs in details and decoration, but the Book of Mormon invokes those biblical stories for readers who have eyes to see, for narrative blindness can lead to moral and political blindness.

Two details in the conflict story between King Noah and Abinadi point back to the biblical Noah; the metalepsis develops out of two hints: the name both Noahs bear and the vineyard that both Noahs plant to produce the grapes for wine. What Hays says about the New Testament is just as accurate regarding the Book of Mormon: “If we want to understand what the New Testament writers were doing theologically — particularly how they interpreted the relation of the gospel to the more ancient story of God’s covenant relationship to Israel — we cannot avoid tracing and understanding their appropriation of Israel’s Scriptures.”20 A large part of the alluding story’s meaning is carried by that space, too often ignored or too little examined, between the referring and the referred to stories.

The events recounted in Genesis are intended to be archetypal — paradigmatic patterns — in which first events model and establish precedent in the world and society they introduce. Those events in what biblical scholars call the Primeval History (Genesis 1–11) lay out the pattern of God’s relationship to humans and human relationships with each other in society. That Primeval History outlines three beginnings, not just one, to represent the new world(s): (1) Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, (2) Adam, Eve, and their progeny after the expulsion into the lone and dreary world, and (3) after the deluge and Noah’s charge to repopulate a recently baptized world. Each of the three events and worlds needs to be seen in relationship to each other. “Each of the three beginnings of humankind is characterized by a sin or fall: Adam’s and Eve’s eating of the fruit, Cain’s murder of Abel, and Noah’s violation” after his drunken exposure.21 For my purposes in this review, Noah’s planting [Page 19]a vineyard, producing wine, and his subsequent drunkenness are the most important, but some treatment of the previous two introductions of humans into new creative orders needs to be seen as the backdrop to the King Noah narrative. All Hebraic scripture demands a reader who is sensitive to the allusive qualities of the material being read: and what is true of the New Testament is just as true of the Book of Mormon, for “the New Testament itself can be understood only in light of a profound theological reading of the Old Testament.”22

Because we have been disciplined to think as moderns, we must be schooled to reason and narrate outside our linear and unidirectional conceptual schemes and historical notions to understand ancient patterns of thought. We must recognize that, as with the Dead Sea Scrolls, the New Testament, and the Hebrew Bible itself, we must read the Book of Mormon in near constant dialogue with the record that Lehi risked his sons’ lives to obtain from Laban. “Every text of the Hebrew Bible opens a window to other biblical texts and to postbiblical interpretations.”23 We exist in a living tradition, and we moderns need to acknowledge that we, in our own way, are doing what Second Isaiah was doing when appropriating the religious tradition to which he belonged. “It follows that the religion which generated the Hebrew Bible in a crucial respect resembles the religions generated by the Hebrew Bible. Israelite thinkers, like those of Judaism and Christianity, looked back to existing texts and constructed new works in relation to those earlier ones,”24 and we stand little chance of understanding this if we don’t understand that.

The Two Noahs

To understand the politeia in the book of Mosiah, we must understand the typological connections between the biblical Noah and King Noah. The name of King Noah should by itself alert the reader to the symbolic link between the two characters. In some important ways that guide the reader along the path to meaning, what happens to the biblical Noah happens to the Book of Mormon Noah. The story of the first Noah is [Page 20]important because he functions as a second Adam. Of Noah and his vineyard, Steinmetz notes that “it is the first vignette that we are offered of the postdiluvian world, indeed the only thing we know about Noah after the flood story is completed. As such, I think, it describes for us what this new world is like.”25 Noah’s world and the vineyard in it aren’t merely retrospective, in that they attempt simply to repeat the world of the Eden, but they reflect the divine command to exert dominion over the created order: “Thus, Noah’s vineyard is not a return to primitive Eden, but a development of Eden in accord with the implicit eschatology of Genesis 1–2.”26 Adam and Noah are charged with completing and expanding the creative work that occurred in Eden by cultivating the creation and extending it. Since the Bible views Noah’s world as the one we still inhabit, understanding the meaning the author attributes to it is essential. Noah’s is the third world described in the Primeval History, and comparison with the first two worlds (the Garden and the lone and dreary world after expulsion) is essential to grasping the biblical view of our created order. Each world is characterized by a transgression or fall from grace: the humans’ partaking of the fruit, Cain’s murder of his brother, and Noah’s drunkenness.27 The murder perpetuated by Cain introduced a mimetic contagion, for after Noah’s arrival but before the flood, human society had devolved into mayhem and bloodshed: “The earth also was corrupt before God, and the earth was filled with violence” (Genesis 6:11). God sees the violence and decides to start over with a new Adam and a new world because “God saw that the wickedness of man was great in the earth, and that every imagination of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually” (Genesis 6:5), and “it repented the Lord that he had made man on the earth, and it grieved him at his heart” (Genesis 6:6). After seeing the level of corruption and violence, God telegraphs his plans to Noah: “God said unto Noah, The end of all flesh is come before me; for the earth is filled with violence through them; and, behold, I will destroy them with the earth” (Genesis 6:13).

The Noah-as-Adam story is what Sonnet calls a false start narrative. God’s attempt to replicate humans and their societies in the divine image proves problematical, if not a failure, so God decides to start over from the beginning with recalcitrant humans, with the Noachide covenant, [Page 21]the Abrahamic covenant, the Mosaic covenant, the Davidic covenant, and others: “Each of the covenants that govern biblical history — the creation covenant, the covenant with the people of Israel (grafted upon the covenant with Abraham), and the monarchic covenant — has had a ‘false start,’ which included an act of repentance coming from God.”28 In each of the founding stories the humans inhabit a new world, and “each of them tells of the first act of violation perpetrated in a new world. In addition, Adam, Cain, and Noah are each described in relation to the earth”29 because some planting occurs: the tree in the garden, Cain’s vocation as a farmer, and Noah’s vineyard. The deluge is a dissolution of the first created order that permits the watery chaos to de-create the original work of God’s organizational act.30 The process of the deluge’s receding and the land emerging, the animals disembarking and God’s blessing the Noah group and issuing virtually the same creation and reproduction mandate Adam and Eve received shows that “the flood account is a historical action of new creation”31 parallel to the first one. Each transgression results in a curse, and part of that curse in the Adam and Eve story and the vineyard story is related to human nakedness and sexuality.32 Similarly, King Noah inherits a world not entirely new but at least renewed by his father (King) Zeniff; keep in mind that the new worlds of Adam and Eve and of Noah are born or reborn under the divine initiative. The new world that Zeniff attempts to recover and King Noah continues is nowhere labeled a divine scheme. In fact, Zeniff himself calls his program of recolonizing the Land of Nephi an “overzealous” project (Mosiah 9:3, the description is used another time: 7:21, of King Zeniff the account says “he being over-zealous to inherit the land of his fathers”) initiated by humans, not God. And Zeniff himself is only a bit player in the Zeniffite campaign: the real focus is his son, King Noah, and the antagonistic prophet Abinadi. Nephi and the Lehi group had literally gained a new world when they migrated out of Jerusalem (the land of promise; 1 Nephi 18:23); Zeniff and his group attempt a paradise regained. Why else would Zeniff name his heir Noah?

[Page 22]Sometime after arrival, Lehi dies, and Nephi leaves this land of first inheritance to escape his brothers’ murderous designs and possesses a new, new world, the land of Nephi (2 Nephi 5:8). Years later, Mosiah1 migrates from the land of Nephi (Omni 1:12) and settles in the land of Zarahemla. Later, under Zeniff’s leadership, a group of Nephites return to inhabit “the land of Nephi, or of the land of our fathers’ first inheritance” (Mosiah 9:1), which they intend to redeem and possess (not the least from Lamanite control): a brave new world, a brave new land (even if a repetition of place and action from earlier generations). Just as Adam is a gardener and the tree of knowledge dominates the garden’s landscape, Cain (as opposed to Abel, who is a pastoralist) is also a farmer, and both Noahs plant a vineyard. A vineyard is different from, say, wheat or oats. Grains don’t require as long-term a commitment to a particular piece of ground: a season from planting to harvest. But a grape vineyard demands a three-year commitment before it begins to yield fruit suitable for wine making. Noah the mariner and Noah the ruler are committed long term to the land they cultivate. All four of these Adam figures are men of the earth: “each story begins with a planting; the tree of knowledge, Cain’s produce, and Noah’s vine each set the stage for the fall that is to occur,”33 with apparently both pride and planting which precede a fall.

In fact, Noah is not only the antitype of the typological Adam, the Genesis text expresses hope that he will undo the curse that Adam brought on humans and the creation. After the fall, “the locus of humanity’s discomfort is their work and toil, and the source of their comfort will be the ground, despite YHWH’s curse. The first person plurals indicate that Noah will be a representative for all humanity, paralleling Adam’s role.”34 Genesis 5 gives a false etymology (perhaps disputed is a better description) of Noah’s name when Noah’s father (no philologist) recounts the human genealogy: “And [Lamech] called his name Noah, saying, This same shall comfort [nachum] us concerning our work and toil of our hands, because of the ground which the Lord hath cursed” (Genesis 5:29). Noah’s name is based on the Hebrew word “to rest,”35 not “to comfort.” This desired reversal of the curse upon [Page 23]the ground and the humans connects Noah more closely to Adam as a savior figure who holds promise to fix the difficulties resulting from the fall. “This, in fact, is one interpretation of the significance of planting the vineyard; Noah, for the first time since Adam’s sin, brings forth comfort from the earth.”36 The original plants in the Garden were sown or transplanted by God, but the plants cultivated by Cain, Noah, and King Noah were placed there by human initiative. Once the humans are forced into the fallen world, they have to plant, cultivate, and harvest (and in the case of grapes, further refine the produce of the ground) the [Page 24]crops themselves. Lamech’s hope for his son is that Noah will redeem the land from the curse accompanying the fall (from toil and thorns), just as Paul believes that a second Adam will reverse the effects of the fall and redeem all of mankind (1 Corinthians 15:45–49).

When God promises never again to curse the ground (Genesis 8:21–22), Noah’s first act after receiving the creation mandate is to plant a vineyard, which “is his act of faith that demonstrates his confidence that the new creation will endure according to God’s promise. Because a vineyard requires at least three years of care before it produces suitable fruit, … Noah’s act represents substantial investment in the current creation”37 and its durability. The Genesis narrative goes to great lengths to convey that the Noah story is a repetition of the two previous creation stories which result in the human inheritance of a newly founded order.

The Noah story is more important in that the text asserts that Noah’s world is still our world; God has not de-created and re-created the world since Noah’s time. Noah is exemplary for the cosmos in which he is the model and first man. “We must read the vineyard story in the context of the prior creations and violations and that such a reading will provide a description of human existence in the new — and real-world.”38 The King Noah narrative so obviously triggers an allusive connection to the biblical Noah. Each transgression is tied in some way to “the awareness or seeing of nakedness, and the intimation of sexuality or sexual sin.”39 The verse before the Book of Mormon mentions King Noah’s vineyards and drunkenness, noting the sexual sins of King Noah and his sycophants: “And it came to pass that he placed his heart upon his riches, and he spent his time in riotous living with his wives and his concubines; and so did also his priests spend their time with harlots” (Mosiah 11:14). King Noah’s sins are much more wide-ranging than just carnal sins, but the story’s chronicler highlights the sexual: “he did not keep the commandments of God, but he did walk after the desires of his own heart. And he had many wives and concubines. And he did cause his people to commit sin, and do that which was abominable in the sight of the Lord. Yea, and they did commit whoredoms and all manner of wickedness” (Mosiah 11:2).

The three biblical stories of new beginnings in a novel world need to be wound together with the King Noah narrative, because that is what the Book of Mormon’s allusive quality demands that we understand. The [Page 25]Zeniffite experiment of redeeming the land of the first inheritance is also a failed experiment and false start after King Noah’s failed one-term kingship, as both the Saulide and Davidide monarchies disintegrated into oppression and violence. The lesson isn’t lost on King Mosiah2, who, after the two splinter groups of Zeniffites rejoin the main Nephite current with their story of King Noah’s oppressive rule, persuades the Nephites to abandon kingship. God repents after the Adamic covenant (Genesis 6:6) — a the covenant with newly freed Israelites narrated in Exodus 34 (Exodus 32:12, 14), and the monarchical covenant of making Saul king — and starts anew with David (1 Samuel 15:11, 29, 35). “In all three divine commitments, time is re-launched after a catastrophe and is endowed with a new quality,”40 and in the case of King Noah’s fall, a new constitutional order.

The Israelites’ failed experiment with monarchy sets a pattern for biblical writers, so the model of false starts isn’t just apparent in the Primeval History, but “the paradigm of God’s repentance and resilience is to be found in the ‘false start’ of monarchic history” also.41 Sonnet refers to Meir Sternberg’s exposition of biblical meaning. For the biblical writers (and also Book of Mormon composers and editors) God repeats patterns in history that humans too often don’t perceive, except in hindsight, and by reading the sacred record with prophetic tutoring. One biblical narrative is linked to others, and the job of the biblical reader is to see the connections, for

in a God-ordered world, analogical linkage reveals the shape of history past and to come with the same authority as it governs the contours of the plot in fiction [in Genesis and the rest of the Hebrew Bible]. … As one cycle follows another through the period of the judges, the Israelites thus stand condemned for their failure to read the lessons of history: the moral coherence of the series luminously shows the hand of a divine serialize[r].42

That same analogical thought process ought to be extended to Book of Mormon narrative in general, and the story of King Noah in particular. Samuel’s caution about kingship warns that the king will appropriate the Israelites’ sons and daughters for his own service, [Page 26]confiscate their land and produce, and “will take one-tenth of your flocks, and you shall be his slaves” (1 Samuel 8:17, NRSV). Samuel’s rebuke echoes the Israelite experience of slavery in Egypt. Enthroning a king will result in a repetition of Egyptian bondage, but this time to an Israelite king instead of an Egyptian Pharaoh. “Samuel’s exhortation indicates how systematic subjugation can emerge from prosperity. Only because one already possesses ‘fields, vineyards, and olives’ can these be confiscated. The more productive one’s land and flocks, the more these can be taxed. The more children one has, the more who can be conscripted.”43

Under Zeniff, King Noah’s father, the Nephite group realizes their theological and eschatological goal of inheriting and possessing the land of their fathers, and they prospered in it. “We did inherit the land of our fathers for many years, yea, for the space of twenty and two years” (Mosiah 10:3). That prospering in the land is specified in the production of fruit and grain, linen and cloth to the extent that the Zeniff group “did prosper in the land” (Mosiah 10:4–5). But after Zeniff “conferred the kingdom upon Noah, one of his sons” (with no mention of Zeniff’s apparent death) (Mosiah 11:1), the successor king demonstrates the potential for a return to slavery much like a return to Egypt. A prophet emerges who predicts such descent into Egyptian-like slavery: “Thus saith the Lord, it shall come to pass that this generation, because of their iniquities, shall be brought into bondage, and shall be smitten on the cheek; yea, and shall be driven by men, and shall be slain” (Mosiah 12:2). When King Noah’s priests interrogate Abinadi, it is obvious that they believe they have possessed the land of first inheritance and redeemed it, achieving some eschatological goal.

When Kings and Prophets Don’t See Eye to Eye

Joseph Spencer’s reading of the confrontation between King Noah and Abinadi is insightful for what it reveals about the theological motivations of King Noah and his priests (no doubt those rationales handed down from Zeniff are the main driving force for the reclamation project). The priests, at Abinadi’s trial, recite Isaiah 52:7–10 and ask why the prophet seemingly contradicts Isaiah’s beatific predictions. These priests take for granted that this passage “had a single, obvious, incontrovertible [Page 27]meaning — a meaning that everyone in the Land of Nephi would immediately see. Such an interpretation would have to have been well-known and rooted in a culture-wide ideology.”44

These Zeniffites apparently had a theological goal to reclaim the land of first inheritance, and they used a variety of typological interpretation, applying Isaiah’s prophetic oracle to themselves: “Because Zeniff seems to have seen himself as an eschatological figure, he likely would have seen Isaiah less as spelling out the still-future history of Israel than as detailing the present history of Israel — the history he and his people had lived out.”45 Prophets like Abinadi with their message of doom and repentance were no longer needed, because “the good tidings of the eschatological restoration of Nephi’s kingdom had been definitively delivered, prophets (Isaiah, Nephi) and kings (Zeniff, Noah) had finally seen eye to eye and together lifted up the voice to sing praises.”46 History had come to an end, and pesky, nattering, nabob prophets like Abinadi had been made obsolete. Of course Abinadi prophesies no end of history, as a Francis Fukuyama might, but asserts that history had not culminated but was actually repeating itself: a human descent into wickedness and violence, in this instance led by their king. Initially, the project of repossessing the promised land of first inheritance achieves its eschatological goals, in the Zeniffite view, for “we again began to establish the kingdom and we again began to possess the land in peace” (Mosiah 10:1), and the ground yields its produce in abundance: “And I did cause that the men should till the ground, and raise all manner of grain and all manner of fruit of every kind” (Mosiah 10:4). The promise first given to Nephi of prospering in the land (“And inasmuch as ye shall keep my commandments, ye shall prosper, and shall be led to a land of promise; yea, even a land which I have prepared for you; yea, a land which is choice above all other lands” 1 Nephi 2:20) is fulfilled (Mosiah 11:5), and they successfully defeat the Lamanites militarily (Mosiah 10:20). Nephi had been promised that if he and his descendants were righteous he would be made a ruler (1 Nephi 2:22). Zeniff and his people, according to this interpretation of Isaiah, think they have fulfilled not only the positive vision of Isaiah but also the promises made to the fathers, Nephi in particular. That is the Zeniffite condition when Zeniff turns monarchy [Page 28]over to his son Noah: “I, being old, did confer the kingdom upon one of my sons; therefore, I say no more” (Mosiah 10:22).

The priests as King Noah’s agents are asserting a theological and textual interpretation, Spencer notes; and Abinadi is challenging the typological meaning of “likening the scriptures” predominant among the Zeniffites. Against this reading of scripture and history, King Noah is not a new Adam, argues Abinadi, redeeming his people from the fall and liberating the land from the curse, as he plants and harvests grapes from a vineyard and other crops to repeat the gardening activities of the first Adam and the first Noah. This farming and harvesting is symbolic of all the consequences of the fall, and Lamech holds out hope that Noah would redeem the land from the curse wrought by Adam: “And he called his name Noah, saying, This same shall comfort us concerning our work and toil of our hands, because of the ground which the Lord hath cursed” (Genesis 5:29).

King Noah asserts that the Isaiah passage foretells their own time when they themselves are empowered to declare “how beautiful upon the mountains are the feet of him that bringeth good tidings; that publisheth peace; that bringeth good tidings of good; that publisheth salvation; that saith unto Zion, Thy God reigneth” (Mosiah 12:21). Abinadi, they counter, is declaring the need for future repentance and punishment rather than declaring peace, good tidings, comfort, and redemption in the present tense. Isaiah foretold a time when any gospel message would “break forth into joy; sing together ye waste places of Jerusalem; for the Lord hath comforted his people, he hath redeemed Jerusalem” (Mosiah 12:23).47 Noah’s priests instead maintain that Abinadi is wrong: “And now, O king, what great evil hast thou done, or what great sins have thy people committed, that we should be condemned of God or judged of this man? … And behold, we are strong, we shall not come into bondage, or be taken captive by our enemies; yea, and thou hast prospered in the land, and thou shalt also prosper” (Mosiah 12:13, 15). Lamech hoped for “comfort” from his son Noah, and Zeniff returns to the land of Nephi in the belief that the Lord through this act of redeeming their symbolic Jerusalem had “comforted his people.” The Book of Mormon reader needs to see how the messages of King Noah and Abinadi are diametrically opposed, and the conflict of interpretation is borne out in their typological views and readings of Isaiah.

[Page 29]Abinadi has to reorient the theological and historical interpretation of Zeniffite society. He first teaches the priests the ten commandments, imperatives their society, the priests, and King Noah have been violating. Then Abinadi teaches the true meaning of Isaiah’s messianic prophecies. The suffering servant songs of Isaiah are yet to be fulfilled, for the messiah must first come as a suffering messiah, who shall take the world’s sins upon himself and die (Mosiah 15:7–12). That future redeemer is the one spoken of by Isaiah, as Abinadi echoes back to the priests the passage they quoted from the scripture and prophets such as Abinadi are still needed, for

Behold I say unto you, that whosoever has heard the words of the prophets, yea, all the holy prophets who have prophesied concerning the coming of the Lord — I say unto you, that all those who have hearkened unto their words, and believed that the Lord would redeem his people, and have looked forward to that day for a remission of their sins, I say unto you, that these are his seed, or they are the heirs of the kingdom of God. …

Yea, and are not the prophets, every one that has opened his mouth to prophesy, that has not fallen into transgression, I mean all the holy prophets ever since the world began? I say unto you that they are his seed.

And these are they who have published peace, who have brought good tidings of good, who have published salvation; and said unto Zion: Thy God reigneth! And O how beautiful upon the mountains were their feet! And again, how beautiful upon the mountains are the feet of those that are still publishing peace! And again, how beautiful upon the mountains are the feet of those who shall hereafter publish peace, yea, from this time henceforth and forever! (Mosiah 15:13, 15–17)

Prophets, Abinadi notes, were essential in the past, in the present, and will be required “from this time henceforth and forever!” The Zeniffite celebration of their achievements in redeeming the land is a wrongheaded and mistaken interpretation of Isaianic and Nephite scripture. King Noah’s name — whether based on the Hebrew word to comfort or to rest — and the allusion to the biblical Noah account is key to understanding the Zeniffite portion of the book of Mosiah. King Noah has brought unrest to the land and the people instead of rest.

[Page 30]Kings and Other Oppressors

King Noah is the prototypical evil king whom the descendants of Abraham encountered time and again in scripture. Biblical narrative provides a few examples of good kings: Josiah, Hezekiah, Solomon in the first half of his life, David (a king without flaws, if the account in 1 Chronicles is to be taken at face value). The Book of Mormon explicitly compares bad King Noah with good kings Benjamin and Mosiah2. I have pointed out the way the King Noah narrative is to be seen against the biblical Primeval History, especially the story of Noah. The Noah narrative establishes the biblical framework for the world we live in now, having been preceded by other world formations with higher expectations and aspirations for human conduct in the Garden and the lone and dreary world. The Noachide, Abrahamic, and Mosaic covenants are attempts by divinity to establish proper relationship between humans and between God and humans, but God had renounced another total reboot in the flood episode. The establishment of monarchy among the Israelites is just another extension of that Noachide world.

Just as the movement from one Adam to the next and the next results in the humans’ taking more and more responsibility for themselves in planting and nurturing the fruit of the ground, and the same is true as we move through the Primeval History, as humans take more and more responsibility for their sins. “Both Adam and Eve, when accused by God, cast blame on others rather than accepting personal responsibility for their actions” (Adam blames Eve, Eve blames the serpent).48 In the next generation, Cain can’t shirk the responsibility for his fratricide onto others. When Cain is angry that God doesn’t accept his sacrifice, Cain is forced to accept that he himself is a moral agent, answerable for what he himself has done. “Cain is enjoined to accept responsibility for his actions. Cain’s sin, in fact, results from his refusal to assume such responsibility and his choice, instead, to destroy the object of his blameful anger.”49 Steinmetz asserts that Genesis 3:18 and 4:7 call on Eve and Cain to accept their own moral culpability. “These clearly parallel statements, I believe, have the same import: although you may be seduced to sin, you have the power to rule over that which lures you,” so each human is responsible for choosing between good and evil.50

[Page 31]Similarly, when the two Nephite assemblies attempt to restore kingship after the disastrous events of King Noah, Alma1 and Mosiah2 use this exact argument about each person being accountable as moral agents for themselves. Citing the example of King Noah, who “did cause his people to commit sin” (Mosiah 11:2), Alma1 urges his group not to shift their righteous responsibilities onto a king or a teacher:

Now as ye have been delivered by the power of God out of these bonds; yea, even out of the hands of king Noah and his people, and also from the bonds of iniquity, even so I desire that ye should stand fast in this liberty wherewith ye have been made free, and that ye trust no man to be a king over you. And also trust no one to be your teacher nor your minister, except he be a man of God, walking in his ways and keeping his commandments. (Mosiah 23:13–14)

Mosiah2, also reverting to the example of wicked King Noah, notes that people have too often shifted their moral accountability to their leaders: “For behold I say unto you, the sins of many people have been caused by the iniquities of their kings; therefore their iniquities are answered upon the heads of their kings” (Mosiah 29:31). But such an arrangement is morally inadequate.

Mosiah2 finds this moral blame-shifting to be unsatisfactory, and he calls it an instance of inequality. Equality in the Book of Mormon means that people take responsibility for their own moral or immoral decisions: “Now I desire that this inequality should be no more in this land, especially among this my people; but I desire that this land be a land of liberty, and every man may enjoy his rights and privileges alike” (Mosiah 29:32). Mosiah related to the people the burdens he himself had borne, with the hope that a more egalitarian solution would help the people take responsibility rather than shift censure or credit to a king. “And he told them that these things ought not to be; but that the burden should come upon all the people, that every man might bear his part” (Mosiah 29:34). Equality is achieved when the people accept accountability for their own moral choices and actions. The Nephites are persuaded by Mosiah2’s argument and accept this form of equality: “Therefore they relinquished their desires for a king, and became exceedingly anxious that every man should have an equal chance throughout all the land; yea, and every man expressed a willingness to answer for his own sins” (Mosiah 29:38). This moral accountability is the very purpose of the Eden, Cain, and Noah stories in Genesis. Partaking of the fruit of knowledge of good and evil includes such culpability and reward. “Human beings are responsible for [Page 32]their own deeds; once the human being achieves the capacity to choose between good and evil, blame for sin cannot be cast upon any external agent.”51

The biblical account establishes the larger backdrop against which Book of Mormon kings are to be compared and contrasted. The Israelites’ suffering under the oppression of kings is analogous to their Egyptian experience under Solomon and later kings. “The first signs of oppression come in Solomon’s reign. The royal bureaucracy can now put endless dainties on the king’s table, and while internal taxation clearly receives a substantial boost from foreign tribute, impressed Israeli labor reaches four months a year for each of 30,000 men (1 Kgs 4–5).”52 Solomon is the oppressor king, the model of kingship warned about in Samuel’s manner of the king: using forced labor for his building projects.53 “The fact is that Solomon was the Israelite king who came closest to living up to this forbidding picture, and it is not credible that anyone familiar with Israel’s history, and concerned about the break-up of its united kingdom, should have been unaware of this fact.”54 Solomon’s son and successor Rehoboam (no Dale Carnegie student) suggests that his father was a piker when it comes to Egyptian-like bondage: “‘Now my father loaded you with a heavy burden, and I will add to your burden; my father punished you with whips and I will punish you with scorpions’ (1 Kings 12:14).”55 If the northern tribes accept Rehoboam’s kingship as they endorsed his father’s, they will have made a covenant on those terms. Solomon started the process of converting prosperity in the land into bondage and servitude, a land of milk and honey into a land of oppression and taxation. King Solomon systematically violated the law of the king,56 as did King Noah. In fact, Samuel predicted that the newly appointed kingship function would oppress the people by taking ten percent of their produce. Now ten percent doesn’t seem so oppressive, for a government needs revenue, as Halpern notes: for ancient or modern readers “the king’s predilection for tithing seems … more responsible than corrupt”;57 of course Samuel describes the manner and taxation of [Page 33]future kings in a period without a central government and state, one with only localized infrastructure and defense expenditures, so a ten percent taxation rate might in such circumstances seem like a policy initiated by a king of debt and an emperor of taxation. The description of King Noah ensures that the reader see his taxation as oppression and corruption by noting that it is not only twice the going rate of kingly taxation at one fifth, and not only on the agricultural production as Samuel warned, but also on precious metals (Mosiah 11:3). King Noah is twice the oppressor Solomon was.

Just as Adam and Eve’s transgression results in the curse of hard labor to produce food and children, Cain’s curse makes him a vagabond and a wanderer; similarly, Noah’s drunken nakedness and Ham’s mocking of that posture results in a curse on Ham’s son. When Abinadi pronounces judgment on King Noah’s wickedness, he delivers a curse that the Zeniffites will experience bondage and suffering (Mosiah 11:20–25). In the Mosaic regime (as opposed to the kingly Davidic regime), prophets occupy the rulership slot. After regime change to a system ruled by kings, the prophet still has a central role with three functions: king makers, king critics, and king removers, while the tribes can join the prophet in these three functions.58 Abinadi needs to be seen in this same function, or at least operating as the king critic and moving force as king remover. Both King Noah and Abinadi need to be seen as inheritors of a long line of biblical precedents.

We often use the word type or variations, such as typology, when we read the Bible or the Book of Mormon (archetype, typical, typify, Robert Alter’s type scene, typecast, prototype); and much of our language about printing comes from the same etymological roots: typography, typist, typeface, typesetter, typewriter. The etymology of the Greek word points to a substantial original, and the antitype is a copy, just as a hammer would leave an indentation in wood, and a printing press or typewriter leaves an ink spot and impression on paper that matches the metal type. The vocabulary emphasizes the typicality of some object or idea. These words come from the Greek typos, sometimes transliterated as tupos. The Latin translation of type is figura, from which we derive in English, and [Page 34]most other languages influenced by classical or church Latin, a range of words regarding metaphor: figuration, figurative language, figure of speech. “The terms typology and figural interpretation are essentially synonymous, though the latter more clearly emphasizes the act of reception by the reader.”59

The word archetype comes from Greek roots meaning “original or foundational” and “pattern or model.” Gore points out that King Noah is “an archetype for iniquity” (p. 106) and is understood to be a typical example of a wicked ruler. When the word typos or its plural typoi (or synonyms such as paradeigma, a “pattern or example”— one can see the English paradigm in it) are used in the New Testament, the reader should be reminded that the acts of God and of humans are repetitive, following some established pattern. King Noah was a bad king because he “lived in-and-for-himself” (p. 108), which is the way of the world. Such degeneracy in high station “shows that corrupt leaders can corrupt the people” (p. 110). This living-in-and-for-oneself is what made King Noah the archetypal evil king. Gore contrasts being-in-and-for-oneself with being-with-and-for-others. Mosiah2 preaches and practices the latter, while King Noah embodied the former philosophy (although Nehor and his order formally introduce the former “as a counterpoint to the regime established by Mosiah” (p. 135)).