[Page 21]Abstract:1 The story of believers being nearly put to death before the appearance of the sign at Christ’s birth is both inspiring and a little confusing. According to the Book of Mormon, the sign comes in the 92nd year, which was actually the sixth year after the prophecy had been made. There is little wonder why even some believers began to doubt. The setting of a final date by which the prophecy must be fulfilled, however, suggests that until that day, there must have been reason for even the nonbelievers to concede that fulfillment was still possible; yet after that deadline it was definitively too late. An understanding of Mesoamerican timekeeping practices and terminology provides one possible explanation.

One of the more interesting — and more perplexing — stories in the Book of Mormon is that of Samuel the Lamanite’s prophecy (and its fulfillment) that Christ would be born in five years (Helaman 14:2–7; 3 Nephi 1:5–21). Samuel’s prophecy is made at some point in the 86th year (Helaman 13:1–2) and declares, “Behold, I give unto you a sign; for five years more cometh, and behold, then cometh the Son of God to redeem all those who shall believe on his name” (Helaman 14:2).

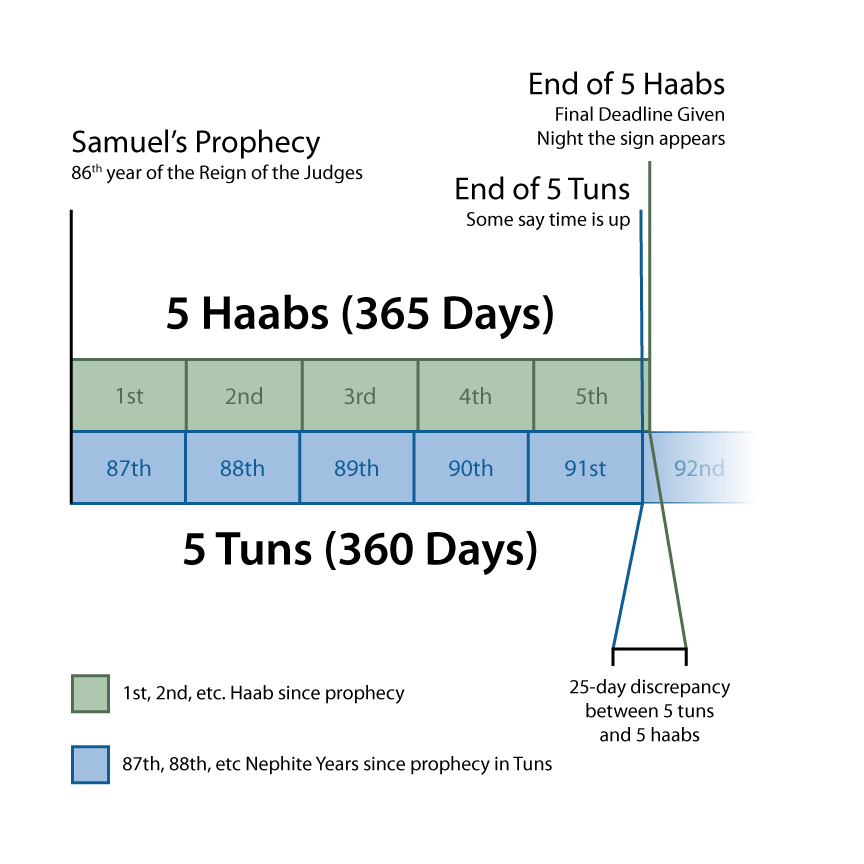

Yet as the 92nd year commenced, the sign had not yet appeared (3 Nephi 1:4–5). At this time, some began to say it was too late for Samuel’s prophecy to be fulfilled (3 Nephi 1:5), and it is easy to understand why — the 92nd year was the 6th year since the prophecy had been given (see [Page 22]fig. 1). Of course, Samuel’s prophecy need not be fulfilled literally five years to the day,2 but even some believers began to doubt (3 Nephi 1:7).

| Fig. 1: Years Counted from When Samuel Gave His Five-Year Prophecy |

|

| 86th Year | Samuel Gives 5-Year Prophecy |

| 87th Year | 1 |

| 88th Year | 2 |

| 89th Year | 3 |

| 90th Year | 4 |

| 91st Year | 5 |

| 92nd Year | 6: Prophecy is Fulfilled |

Despite believing that the time had passed, the skeptics “set apart” a specific day in the 92nd year as the deadline for the prophecy — literally, they planned to “put to death” all who believed in the prophecy, “except the sign should come to pass” (3 Nephi 1:9). Given this was a planned mass execution, it is safe to say this was not an arbitrary date. There was probably some reason for even the unbelievers to think the prophecy could potentially be fulfilled before that day and for believing that after that day it would be definitively too late for the sign to come.

So, for this whole story to make sense, there must be (1) good reason to think the prophecy should have been fulfilled by the end of the 91st year, yet also (2) good reason to think it could potentially be fulfilled if it came by a certain day in the 92nd year, and (3) good enough reason to think that after that day, the time for fulfillment was definitively passed — hence, those who persisted to believe deserved the death penalty.

It’s not hard to find a good reason for the first of these propositions — the 91st year was the fifth year since Samuel had prophesied. John L. Sorenson noted this chronological discrepancy, pointing out “the fulfillment of Samuel’s predictions should have commenced in the 91st year. The initial fulfillment is, instead, reported in the 92nd year.” Thus the peoples’ expectation that the time had passed, “would make [Page 23]sense in terms of a five-year prediction.”3 At some point during the 91st year, five full years had passed from the day Samuel prophesied. Thus, with that year’s completion, it had already been more than five years, and many naturally felt the time had passed.

But what made even the skeptics think there was potential for the fulfillment before a certain day? And what made them confident that after that day, it was definitively too late for the sign to come? One potential answer to these questions can be found in a Mesoamerican setting for Samuel’s prophecy.

Samuel’s Prophecy in a Mesoamerican Setting

Others have already talked about how Samuel’s time-specific prophecies are consistent with important time-periods in the Mesoamerican Long Count calendar system.4 John L. Sorenson, John E. Clark, and [Page 24]Brant A. Gardner all noted that Samuel’s 400-year prophecy correlates with a major time unit in the Long Count, the baktun, which consisted of 400 tuns (360-day years, see below).5 Only Mark Alan Wright has pointed out that the five-year prophecy correlates with the ho’tun, another significant time unit.6

Sorenson did notice another Mesoamerican connection to the five year prophecy. When the Spanish arrived, some Mesoamerican groups had the custom of prophesying the outcome of the next katun five years in advance.7 Samuel was similarly predicting the outcome of the upcoming baktun (Helaman 13:5, 9) five years before it began (Helaman 14:2). While Sorenson cautiously acknowledged that the evidence for this custom was from 1,500 years later, and we cannot be certain the tradition existed in the first century BC, the comparison is nonetheless interesting.

On other hand, we can be confident that the Long Count was known at the right time and the right place. The earliest date recorded in the Long Count system is 36 BC and comes from Chiapas, Mexico, near the Grijalva River.8 Sorenson and others place the greater land of Zarahemla in Chiapas, with the Grijalva River as the Sidon (see fig. 2).9 So archaeological evidence attests to the use of the tun and the Long Count system in the same time and place as Samuel the Lamanite’s prophecy.

[Page 25]

Fig. 2: Earliest Long Count date in the relation to Sorenson’s Zarahemla.

Map by Jasmin Gimenez

The Mesoamerican setting for Samuel’s prophecy also provides a solution to the confusing details about the timing of its fulfillment in an interesting way that preserves the accuracy of Samuel’s prophecy and potentially sheds light on other aspects of Nephite chronology.

The Haab and the Tun

Ancient Mesoamericans had two different time-periods that served as a type of “year.” One was a 365-day cycle, typically called the haab, and the other was a 360-day cycle, commonly known as the tun and part of the “Long Count” calendar.10 While the terms haab and tun [Page 26]are frequently used by scholars in a way that distinguishes the 365-day period (haab) from the 360-day period (tun), among the ancient Maya, the terms were interchangeable.

This is made clear by Michael D. Coe and Stephen Houston, who described the “Ha’b of 365 days,” but then, while discussing the 360 day tun, noted, “in a switch sure to confuse modern readers, the tun was really called ha’b!”11 Lars Kirkhusmo Pharo said the Long Count used a “haab of 360 days” and then explained, “Tun is the Yucatec word for haab, which is a Yucatec designation for a year of 365 days.”12 Pharo laid out an entire haab-based lowland Maya terminology for the Long Count system, “with Yucatec designations in parenthesis” as follows:

Pik (Bak’tun): 144,000 days

Winikhaab (K’atun): 7,200 days

Haab (Tun): 360 days

Winal/Winik: 20 days

K’in: 1 day13

The exceptions to this haab-based terminology were five-year intervals in which “the classic inscriptions of the southern lowlands employ the designation tun for periods of 5 (ho’tun), 10 (lajun tun), or 15 (ho’lajun tun) haab.”14

John S. Justeson and Terrence Kaufman likewise explained the interchangeable use of these terms, noting that the Long Count “used 360 days as a canonical year length; among the Mayans, the word ha7b’ (‘year’) was used for both this period and the older 365-day year,” and the “tu:n referred to anniversaries using either year length … and not, as is often stated, to the 360-day year per se.”15

[Page 27]To avoid confusion, the convention of using haab for the 365-day year and tun for the 360-day year will be maintained throughout the rest of this article, but it is important to remember that among the ancient Maya, the terms were interchangeable — and periods of either five haabs or tuns would always be called a ho’tun.

Samuel’s Ho’tun Prophecy: Five 365-day or 360-day Years?

If the Nephites and Lamanites lived in Mesoamerica, they most likely would have been familiar with both the haab and the tun, and like the Maya, they probably would have used the same word for both types of year. Thus, when Samuel made his five-year prophecy, he would have used the Nephite equivalent term for ho’tun, which could have referred to five haabs or five tuns — which makes for a difference of 25 days (see fig. 3).16

This, in turn, could have led to the scenario found in 3 Nephi 1. Some — perhaps everyone, initially — may have interpreted the prophecy to be fulfilled after five tuns. When five tuns passed at the conclusion of the 91st year, skeptics “began to rejoice” arguing, “Behold, the time is past, and the words of Samuel are not fulfilled; therefore, your joy and your faith concerning this thing hath been vain” (3 Nephi 1:6). Some who believed even feared that they may be right and were “very sorrowful” (3 Nephi 1:7).

Others, however, “did watch steadfastly” for the prophesied sign, “that they might know that their faith had not been vain” (3 Nephi 1:8). For these steadfast believers, the possibility that Samuel meant five haabs may have given them hope that it was not too late for the sign to come. The skeptics had to acknowledge this as a viable interpretation of the prophecy, so they marked the day five haabs would be completed as the final deadline. If the sign did not come by that day, “all those who believed in those traditions should be put to death” (3 Nephi 1:9).

[Page 28]

Fig. 3 Dual Timeline Showing the Passing of the Haabs and Tuns.

Chart by Jasmin Gimenez

Implications for Book of Mormon Chronology

This solution works best if the “years” the Nephites were counting off from the start of the reign of the judges were tuns — 360-day years.17 Otherwise, the passing of the 91st year would have also concluded the passing of the fifth haab since Samuel’s prophecy, and there would be no additional 25-day period to hold out hope for.

This would suggest the other Nephite year systems — counting from the time Lehi left Jerusalem and the counting from the time the sign was [Page 29]given — were also tuns, since these three calendars were in sync with each other (3 Nephi 2:5–7).18 Proposals by previous scholars that the discrepancy with the 600-year prophecy can be solved by using tuns19 and correlation with Nephite destruction and the baktun cycle20 further supports this possibility.

Ultimately, however, it must be admitted that this is just one possible explanation for the confusing situation set out in 3 Nephi 1. Whereas there is no way to prove this or any other explanation, the additional Mesoamerican connections found in Samuel’s prophecy lend support to this idea. At the very least, they suggest the solution to this and perhaps other chronological puzzles in the Book of Mormon can be found in the calendrical practices of ancient Mesoamerica.

Go here to see the 25 thoughts on “““The Time is Past”: A Note on Samuel’s Five-Year Prophecy”” or to comment on it.