[Page 97]Abstract: In this article, Michael Morales considers how the building of the Tabernacle had been pre-figured from the earliest narratives of Genesis onward. It describes some of the parallels between the creation, deluge, and Sinai narratives and the tabernacle account; examines how the high priest’s office functions as something of a new Adam; and considers how the completed tabernacle resolves the storyline of Genesis and Exodus, via the biblical theme of “to dwell in the divine Presence.”

[Editor’s Note: Part of our book chapter reprint series, this article is reprinted here as a service to the LDS community. Original pagination and page numbers have necessarily changed, otherwise the reprint has the same content as the original.

See L. Michael Morales, “The Tabernacle: Mountain of God in the Cultus of Israel,” in Ancient Temple Worship: Proceedings of The Expound Symposium 14 May 2011, ed. Matthew B. Brown, Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, Stephen D. Ricks, and John S. Thompson (Orem, UT: The Interpreter Foundation; Salt Lake City: Eborn Books, 2014), 27–70. Further information at https://interpreterfoundation.org/books/ancient-temple-worship/.]

Introduction

That the narratives leading up to the tabernacle have had its cultus in view as a major goal may be surmised by the centrality of the cultus in the Torah, as well as the parallels (lexical and thematic) between those narratives and the tabernacle account.1 By way of introduction, [Page 98]we will consider briefly the former, the centrality of the tabernacle cultus. Unfolding through the events at Sinai recorded in Exodus 19 through Numbers 10, worship via the tabernacle is the literary heart and theological apex of the Torah.2 Even the sheer amount of this narrative is misleading, moreover, inasmuch as much of the literature outside Exodus 19—Numbers 10 has also been demonstrated to be concerned with cultic matters and likely, in Genesis 1—Exodus 18, in such a way as to anticipate Israel’s tabernacle cultus.3

More narrowly, chapters 19-40 of Exodus may be considered, formally, a meticulously composed, coherent story that culminates with the glory cloud’s descent upon the completed tabernacle.4 Justifiably, then, Davies believes “worship” has a strong claim to be the central theological theme of Exodus, linking together salvation, covenant, and law — a theology, what’s more, going back as far as can be discerned in the history of the tradition.5 Now beyond all else to which the tabernacle/המשׁכן cultus and its rituals pertain, one must keep in view the fundamental understanding of it as the dwelling/שׁכן of God (cf. Exodus 25.8-9; 29.45-46), so that “worship” may be defined broadly as “dwelling in the divine Presence.” Already, then, the bookends of the Genesis-through-Exodus narrative begin to emerge: the seventh day/garden of Eden (Genesis 1-3) and the tabernacle Presence of God among his cultic community (Exodus 40).

The building of the tabernacle, then, with the establishment of its cult, may be seen as a major goal of the exodus — a goal that includes the constitution of Israel as a cultic community (עדה ‘edah) living in the divine Presence.6 This goal is evident not only by the centrality of worship in the Torah, but also by explicit statement. At the very outset of the tabernacle narrative, Yhwh’s purpose is manifested: “Let them make me a sanctuary that I may dwell among them” (Exodus 25.8). This narrative goal is repeated in 29.45-6:

I will dwell among the sons of Israel, and I will be their God. They shall know that I am Yhwh their God, who brought them out of the land of Egypt that I might dwell among them; I am Yhwh their God.

That these explicit lines are not merely incidental but programmatic is evident, further, by the lengthy description of the follow-through on the “let them make me a sanctuary” directive. While modern sensibilities find tedious the mass of repetitive material constituting thirteen of the remaining sixteen chapters of Exodus, yet from the ancient Near East [Page 99](ANE) perspective this concentration manifestly brings one to the heart of the narrative.7 The overall movement from slavery to worship, from building for Pharaoh to building for Yhwh8 is in line with parallel ANE literature, such as the Ugaritic epic of Baal and the Babylonian “Epic of Creation,” whereby the building of a victorious deity’s house/temple forms the epic’s climax.9 Thus, comparisons with other building narratives from the Bible (1 Kings 5.15-9.25) and Mesopotamian and Ugaritic sources manifest, not only that the tabernacle story’s overall structure is deliberate and well ordered, following a standard literary pattern or building genre,10 but also the ideological weight of the tabernacle itself. The building section within the larger cycle, furthermore, is itself unified by the recurrent theme that Moses was shown the “pattern” (תבנית tabnît) of the tabernacle by God while he was on the mountain (25.9, 40, 26.30, 37.8),11 a theme functioning to underscore the importance of the cultus. Because insufficient consideration of the tabernacle account necessarily results in a “superficial grasp” of the book’s significance,12 the literary weight of the tabernacle material must be balanced by its theological weight. The dramatic question — and tension — of how the prospect of a return to dwelling in the divine Presence will be made possible via a tabernacle constructed according to the divinely revealed heavenly “pattern,” and this prospect in light of the thunderous fury of the fiery Presence just experienced at Sinai — all this must be impressed upon the reader. The balance of the book of Exodus, to summarize, is devoted to the tabernacle, the establishment of which, far from being a subsidiary interpolation, is the climax of the epic, the resolution toward which that narrative has progressed.13

Glimpsing now a sketch of the tabernacle’s centrality within the narrative progression leading up to it, its function as dénouement will appear more clearly. As the creation account of Genesis 1-3 would surely have catechized its original audience, the high goal of worshiping the Creator in the glory of his Presence upon the holy mount had been frustrated by Adam’s transgression and the consequent exile from the garden.14 The ensuing narrative, rather than normalizing life outside of Eden (so as to make the account merely a story about “lost innocence” or “why things are the way they are,” i.e., an etiology), intensifies the predicament and underscores the issue as crucial to the drama (and, thus, an eschatological point). For example, the use of “to banish” גרשׁ in the Cain narrative (4.14; cf. 3.24) suggests that “in some sense Cain’s exile is a repetition and intensification of Adam and Eve’s exile.”15 This intensification reaches an apex as the profanation of creation (as macro-[Page 100]temple) finally calls for an end/return to chaos, righteous Noah, with his household and a remnant of creatures, being delivered through an ark whose plans are divinely revealed, one of several features serving to portray it as a kind of typological temple. The scattering from the tower of Babel may be interpreted, through an anti-gate liturgy pattern, as a further removal from the Presence of God whose own deliberate plan for allowing re-entrance into the divine Presence begins with the call of Abraham and culminates in the divine in-filling of the tabernacle, Babel and the tabernacle being antipodes in the narrative arc.16 New mediated access to that Presence of life thus becomes, not merely a means of “worship” for the Israelite, but the means by which the order and purpose of creation is reestablished—that is, creation and cult are of a piece.17 Thus Hurowitz is correct in positing that the “crucial event around which all the activities focus is God’s entry and manifestation within the newly built abode.”18 If, as we have seen, the creation account is oriented toward the Sabbath, i.e., life in the divine Presence, then it makes sense that the account of history itself should be like oriented. Understanding the loss of the divine Presence as the central catastrophe of the biblical drama, then one begins to see the tabernacle as mishkan, the locus of God’s Presence in the midst of his people,19 as the (at least initial) resolution.20 As already stated, this dénouement is in accord with the general tenor of the Pentateuch in which numerous stories reflect points of priestly interest.21 The pattern of Exodus, then, offers a glimpse, a micro-narrative, of the entire biblical narrative itself.22

I. THE TABERNACLE PRE-FIGURED

In this chapter we will consider further how the tabernacle cultus “fulfills” plot expectation, the tabernacle’s significance being derived from and infused into the previous narrative(s). We will, accordingly, (1) rehearse some of the parallels between the creation, deluge, and Sinai narratives and the tabernacle account; (2) examine how the high priest’s office functions as something of a new Adam, as the righteous one able to ascend the mount of Yhwh; and (3) consider how the completed tabernacle resolves the storyline of Genesis—Exodus, via the biblical theological theme of “to dwell in the divine Presence.”

A brief overview of the parallels between the creation and deluge accounts and the tabernacle will be considered before we turn to the parallels between Sinai and the tabernacle. Our point will be to understand that the tabernacle subsumes meaning and significance [Page 101]from those previous accounts — it is, in many respects, the Pentateuch’s centripetal force and goal.

A. From Creation to the Tabernacle

Creating the cosmos and building the tabernacle are literarily linked, the latter being a microcosm of the former.23 Blenkinsopp identifies precisely these two accounts as the first two major “nodal points” of (P’s narrative in) the Pentateuch: the creation of the cosmos as a precondition for worship (Genesis 1.1-2.4a), and the building and dedication of the wilderness sanctuary (Exodus 40.1-33).24 While the creation may be understood legitimately in terms of a temple, it is also important to see that the tabernacle/temple constitutes something of a new creation within the old, a micro-cosmos within the macro, designed to mediate the paradisal Presence of the Creator. Thus one is not surprised to find the literary parallels between the creation and tabernacle narratives.25 While not rehearsing those parallels here, we merely recall how the רוח of God is instrumental both in the building of the cosmic temple, the world (Genesis 1.2), and in the micro-cosmic world, the tabernacle (Exodus 31.1-11), the former amidst the chaos of water (תהו), the latter amidst the chaos of wilderness (תהו Deuteronomy 32.10).26 This like source of wisdom/skill/power is matched by like method, both creation and tabernacle construction featuring “separation”/בדל: whereas the firmament is created to “separate” (hiphil participle of בדל) the waters (Genesis 1.6), so the tabernacle veil is to “separate” (hiphil qatal of בדל) the holy place from the holiest place (Exodus 26.33).27 Finally, the chronology of the building projects are also linked: the consecration of the tabernacle lasted seven days, a heptadic pattern connected to the Sabbath ordinances.28 Perhaps above all other parallels, it is the Sabbath linking of the tabernacle to creation that generates the theological profundity and function of the cultus: via the mediation of the tabernacle cultus alone, the purpose of creation may be realized.29 The Sabbath, therefore, forms a bridge, an inclusio, linking creation with cultus as its climax,30 the tabernacle manifestly created as a mini-cosmos oriented to the Sabbath.31

The cosmological parallels between creation and the tabernacle are in accord, further, with the cosmological import of several of the tabernacle appurtenances, as later explained within the temple system.32 The altar is called הראל (also referred to as אראיל) “the mountain of God” (Ezekiel 43.15-16) with its base named חיק הארץ “the bosom of the earth” (Ezekiel 43.14).33 The Basin הים מוצק as well is likely to be read with cosmic [Page 102]significance as “The Sea has been restrained!”34 It also appears evident that the menorah was a stylized tree of life (cf. Exodus 25.31-40).35

The tabernacle, then, “is a microcosm of creation, the world order as God intended it writ small in Israel.”36 The parallels thus established, when Yhwh fills the tabernacle, this is “a sign that the new ‘creation’ has been achieved.”37 Interestingly, the sixth century Egyptian Christian Cosmas, in his book Christian Topography, posited that the creation account of Genesis 1 was Moses’ description of the תבנית shown him atop Sinai, and that “the tabernacle prepared by Moses in the wilderness …was a type and copy of the whole world”:

Then when he [Moses] had come down from the Mountain he was ordered by God to make the tabernacle, which was a representation of what he had seen on the Mountain, namely, an impress of the world. …Since therefore it had been shown him how God made the heaven and the earth, and how on the second day he made the firmament in the middle between them, and thus made the one place into two places, so Moses, in like manner, in accordance with the pattern which he had seen, made the tabernacle and placed the veil in the middle and by this division made the one tabernacle into two, the inner and the outer.38

B. From the Ark of Noah to the Tabernacle

One might also recall the “striking parallels between the tabernacle and the ark of Noah,”39 the ark itself a micro-cosmos. Again, while not detailing the parallels here, we merely note the general correspondence that even as “Noah did according to all that God had commanded him, thus did he” (Genesis 6.22) in relation to the ark, so “according to all that Yhwh had commanded Moses, thus did the Israelites all the work” (Exodus 39.42) in relation to the tabernacle, both narratives emphasizing the New Year (Genesis 8.13; Exodus 40.2).40

When the tabernacle narrative is made to include the broader context of Exodus, then many more parallels are manifest: God “remembering” for the sake of deliverance (Genesis 8.1; Exodus 2.24); sending a “wind” (Genesis 8.1; Exodus 14.21); the appearing of “dry ground” (Genesis 8.13-14; Exodus 14.21-22).41

Ross, further, captures both the parallels and the pattern (through the waters → to the mountain → for worship) when he writes:

[Page 103]Just as God had judged the world in Noah’s day and brought Noah’s family through the Flood, compelling them to worship the Lord with a sacrifice, so he judged Egypt and brought Israel through the waters of the Red Sea to worship and serve him on the other side.42

Scholars have also noted how the salvation found in the ark during the forty-day period of rain parallels that amidst the presence of the tabernacle during the forty-year period in the wilderness.43

As mentioned already with regard to creation parallels, so now with regard to deluge parallels with the tabernacle: while it is legitimate to view the ark in terms of temple symbolism, one has not satisfied the significance of those parallels until the tabernacle itself, as the narrative goal, has subsumed something of the meaning of the ark. Likely, it is the redemptive aspect that informs the parallels between ark and tabernacle, the tabernacle constituting the divinely revealed means of refuge. Here, protology swirls into eschatology, and the cosmogonic pattern proves to be mythic in the sense of being in illo tempore.44 From one perspective, it may be said that Adam’s transgression and expulsion “interrupted” the eschatological goal of the original cosmogonic pattern. For our purposes, we simply note the deluge narrative, as with the creation account, has been shaped with a view to the tabernacle cultus.

C. From Mount Sinai to the Tabernacle

On Mount Sinai, Clifford notes, Yhwh has his tent, and the earthly copy of the tent will mediate his Presence to his people.45 What we would like to consider here is the narrative transition from the former to the latter. To be sure, the narrative accounts of each are linked together. For example, the motifs in Exodus 24.15b-18a of (1) Sabbath chronology, (2) the כבוד of Yhwh, (3) use of the term שׁכן, and (4) the introduction speech formula ויקרא, serve to link the mountain of God with the tabernacle pericope, essentially transforming the covenant ceremony into a preparation in worship for the establishment of the tabernacle cult.46 More specifically, we note first, and simply, that the tabernacle structure itself comes into existence within the sacred space established by the presence of the mountain of God.47 But further, and as early as the elders’ vision of God on Mount Sinai in Exodus 24.10-11, we find a description of the heavenly sanctuary, its blue sapphire being a common feature of temples in the ancient Near East, so that already the theophany of the mountain “gives way to temple imagery,” to “the vision of God in the heavenly temple.”48 [Page 104]Then, of course, the תבנית for the tabernacle is revealed precisely from Sinai’s summit. Dozeman and Niccacci note, significantly, it is upon the seventh ascension that the tabernacle cultus is revealed,49 so that the “revelation and construction of the wilderness sanctuary participate fully in the mythology of the cosmic mountain.”50 This participation in mythology also includes a sharing of terminology. Indeed, the great statement of Exodus 24.16 that would ever after symbolize Sinai, namely, that “the glory of Yhwh dwelled upon Mount Sinai,” begins with the word וישׁכן, offering a preview of the following section’s subject, the work of the משׁכן, so that the tabernacle is a kind of miniature Sinai.51 Consistently, the sacred mountain in Exodus 15.17 (whether precisely identified with Sinai or not),52 the tabernacle (Exodus 25.8; Leviticus 16.33), and the Jerusalem temple (1 Chronicles 22.19; Isaiah 63.18) are each referred to as מקדשׁ miqdāš.

Now since a defining feature of any ANE temple is its being an “architectural embodiment of the cosmic mountain,”53 one would expect parallels between them in that embodiment — such is, in fact, the case. In the following ways the narrative brings out the tabernacle’s function as a portable Sinai:54

- the three districts of holiness common to each;

- Yhwh communicates with Moses from the mountaintop and the Holy of Holies;

- the glory cloud envelops both;

- the two tablets derived from Sinai’s summit are placed in the tabernacle’s parallel Holy of Holies;

- mediation of the divine Presence is via sacrifice.

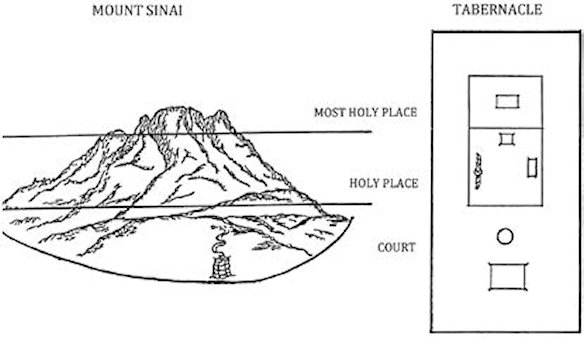

To flesh out each of these points now, Rodriguez offers a helpful summary of (1) some of the architectural similarities between Sinai and the tabernacle, followed by his illustration, in Figure 1:55

The similarity of arrangement here [Sinai] with that of the subsequent tabernacle is striking. The fence around the mountain, with an altar at the foot of the mountain, would correspond to the court of the sanctuary with its altar of burnt offering; the limited group of people who could go up to a certain point on the mountain would correspond to the priests of the sanctuary, who could enter into the first apartment or “holy place”; and the fact that only Moses could go up to the very presence of Yahweh would correspond to the activity of the high priest, who alone could enter into the presence of [Page 105]Yahweh in the inner apartment of the sanctuary, or “most holy place.”

Figure 1: Mount Sinai and the Tabernacle (Sketch by Angel M. Rodriguez)

The Torah, further, brings out the (2) parallel function between mountain and tabernacle as the locus of divine speech (מן־ההר min-hāhār//מאהל mē’ōhel), so that chapters 19-40 may be said to be a story “dedicated to the divine movement from mountain to tent”:56

And Yhwh called to him from the Mountain, saying…

And Yhwh called to Moses and spoke to him from the Tent of Meeting, saying…

Knohl highlights the significance of the tabernacle as a locus of revelation:

Prior to the construction of the tabernacle, God said to Moses, “There I will meet with you, and I will impart to you—from above the cover, from between the two cherubim that are on top of the Ark of the Pact—all that I will command you concerning the Israelite people” (Exodus 25.22). After it was set up, we read, “When Moses went into the Tent of Meeting to speak with Him, he would hear the voice addressing him from above the cover that was on top of the Ark of the Pact between the two cherubim: thus He spoke to him” (Numbers 7.89). God, who is seen above the cover (כפרת), meets Moses there and commands the children of Israel.57

[Page 106]Continuing, Weinfeld provides evidence that (3) the building of the tabernacle is stylistically paralleled to Mount Sinai, specifically with reference to the glory cloud — an idea, he notes, is found already in Nachmanides:58

| Exodus 24.15-16 | Exodus 40.34-Leviticus 1.1 |

| When Moses had ascended the mountain, the cloud covered (הענן ויכס) the mountain. The Presence of Yhwh (כבוד־יהוה) abode on Mount Sinai and the cloud hid it for six days. On the seventh day He called to Moses (ויקרא אל־משׁה) from the midst of the cloud. | … the cloud covered (ויכס הענן) the Tent of Meeting, and the Presence of Yhwh (יהוה וכבוד) filled the Tabernacle. Moses could not enter because the cloud had settled upon it (cf. 1 Kings 8.10-11). Yhwh called to Moses (ויקרא אל־משׁה) … from the Tent of Meeting. |

Cassuto had already noted the poetic parallelism of 40.34 is entirely similar to 24.15-16:59

And the cloud covered the tent of meeting,/

and the glory of Yhwh filled the tabernacle (40.34)And the cloud covered the mountain;/

and the glory of Yhwh dwelt upon Mount Sinai (24.15-16)

Briefly, with reference to (4) the tables of the Law, we simply point out that the places of their origin (Sinai’s summit) and keeping (Holy of Holies) correspond to each other typologically. Finally, another parallel between Sinai and the tabernacle cultus is found in (5) how the problem of the divine Presence amidst a sinful people is remedied — namely, by sacrifice:

The divine Presence in the midst of Israel necessitated sacrifice. This is implied in the connection between the end of Exodus, where the glory fills the ‘tent of meeting’ (Exodus 40.34-35), and the opening verse of Leviticus where Yhwh calls Moses to give him instruction regarding sacrifice. Leviticus 9 records the occasion when the entire worship system commenced operation. The essence of the ceremony is summarized in Leviticus 9.22-24. All elements of Exodus 24.1-11 are repeated: (1) Yhwh appears to the people (the central benefit of the covenant), (2) the priests make sacrifice and peace offerings (a communal meal would follow that celebrates covenant [Page 107]fellowship), and (3) Aaron speaks a word of blessing to the people (implying benefits of the covenant, perhaps similar in content to the blessings defined in Leviticus 26.4-13). The Levitical sacrifices functioned to maintain and celebrate covenant relationship, sanctifying the nation in service of the holy God in her midst.60

Because of the cultic remedy for sin, “the fire that dwells in their midst” does not consume Israel (40.34-38; cf. 3.3, 24.17).61

In conclusion, there appears to be a deliberate narratival catechesis regarding the transition from Sinai to the tabernacle cultus, so that one may understand with Childs that what happened at Sinai “is continued in the tabernacle.”62 This however amounts to a fundamental understatement unless one first views Sinai as the culminating cosmic mountain (subsuming Eden and Ararat in the narrative trajectory toward the tabernacle), the fulfillment of the cosmogonic pattern: through the Sea (Exodus 14) → to Mount Sinai (Exodus 19) → for worship (Exodus 24), and as the summit from which the divine blueprint for the tabernacle, as with the ark of Noah, is revealed. In sum, when the glory cloud transitions from Sinai to the tabernacle Holy of Holies, what is continued in the tabernacle includes Sinai’s summation of creation (Genesis 1-3) and deliverance (Genesis 6-9).

II. THE GATE LITURGY

Throughout the creation, deluge, and Sinai narratives, the gate liturgy question (“Who shall ascend the mount of Yhwh?”) — so we have advanced — runs like an undercurrent. Finding liturgical expression within the context of the Solomonic temple (Psalms 15, 24), the gate liturgy becomes somewhat expected in the setting of the tabernacle. Such is, in fact, the case, as we will go on to demonstrate below. The gate liturgy will be found, however, in much the same way and manner as in the previous narratives — that is, as an undercurrent within the depths of the narrative, a narrative-unfolding ideology shaped by the cosmic mountain. In our attempt to make manifest the gate liturgy within the tabernacle cultus, we will consider the high priest as symbolizing Adam, and then his entrance into the Holy of Holies on the Day of Atonement as an “ascent.”

[Page 108]A. The High Priest as Adam

One cannot understand the tabernacle cultus adequately apart from considering its personnel, the priesthood.63 The role of the priesthood must be understood in light of the overarching conceptual pattern of the tabernacle as a renewed cosmos.64 For his part, the priest represented the restored creation as pertaining to humanity — he had to be perfect as a man.65

Fletcher-Louis fills in a key piece when he notes that “the high priest was also believed to be the true or second Adam. This idea is probably present already in Ezekiel 28.12-16 and is otherwise clearly attested in Sirach 49.16-50.1 (Hebrew text).”66 He notes further that “the Adamic identity of Aaron is fundamental to the theology of P,” with the priest/new Adam “doing what Adam failed to do in the temple-as-restored-Eden,”67 so that, according to the cultic worldview, “the God-intended humanity of Genesis 1 is thus recapitulated, and sacramentally reconstituted, in Israel’s priesthood, in the temple-as-microcosm.”68 That Adam may be considered justly in priestly terms, even as an archetypal high priest, has already been addressed in our second chapter, and such an understanding is also evident from early sources of interpretation.69 In his Legends of the Jews, for example, Ginzberg notes: “On the sixth, the last day of creation, man had been created in the image of God to glorify his creator, and likewise was the high priest anointed to minister in the tabernacle before his Lord and creator.”70 It may even be precisely because he is an Adam-figure that the priest’s sin propagated guilt among the entire people (Leviticus 4.3).71 Even the terms for the priestly garments, כבוד (“glory”) and תפארת (“honor”), forming an inclusio around the account of the vestments in Exodus 28, are used of the glory theophany of Yhwh, demonstrating that “the priest was appropriately attired to enter a renewed cosmos and stand in the presence of the divine resident of this cosmic temple.”72 Thus the priest in the representation or drama73 of the cultus, dressed in such glorious raiment, portrayed humanity in its newly created purity, no longer separated from the divine Presence through the rebellion and expulsion recounted in Genesis 3, but able — as the pre-eminent “holy” person — to ascend the mount, to enter the Holy of Holies.74 It is important to see, further, that the high priest inherited Moses’ role, discussed earlier, as mediator:

One might picture priests as mediating an ascending movement toward God in their installation rite of passage and their holy and clean life-styles and a concurrent descending movement [Page 109]of oracular messages from God, authoritative declarations, trustworthy torah, and effective blessings in Yahweh’s name. The mediating and revelatory role of the priest, the one who by virtue of his office was “near” Yahweh (Ezekiel 42.13; 43.19; compare Exodus 19.22), is well expressed in a popular saying about priests that has God declare: “Through those near me I will make myself holy, and before the entire people I will glorify myself ” (Leviticus 10.3).75

Another parallel between Moses and the high priest’s office may be found in relation to their deaths. As Wenham notes, the high priest’s atonement labors were not only accomplished on the high holy Day of Atonement, but even, finally, through his own death:

At the pinnacle of the system stood the high priest. … These day of atonement ceremonies enabled God to continue dwelling among his people despite their sinfulness. The atoning work of the high priest culminated in his death. This purged the land of the blood guilt associated with violent death and allowed those convicted of manslaughter to leave the cities of refuge and return home (Numbers 35.28, 32).76

This in mind, and returning to Moses, Israel’s hope of entering the land appears throughout the book of Deuteronomy to be theologically connected to the death of Moses — a final gesture of atonement from the one who as mediator served as something of a paradigm for the high priest.77 Moses is portrayed, so notes von Rad, as a “suffering mediator,” whose death outside the land is to some extent depicted as “vicarious for Israel.”78

In relation to the tabernacle, then, there is a sense where Aaron’s role (who, incidentally, was not allowed to enter the top of the mount) was to portray in the drama of liturgy the role of Moses in relation to the cosmic mountain (and thus of Adam to Eden’s mount) — that is, via entering the tabernacle Holy of Holies, the high priest as mediator79 represents the one “able to ascend” the summit of the cosmic mountain.80 To be sure, “ascending the mountain and entering the Holy of Holies amount to the same thing.”81 The cosmogonic pattern in mind, moreover, it is interesting that in the construct of the tabernacle, Aaron and his sons would wash themselves at the laver (cosmic waters?) upon every approach to the altar (cosmic mountain?).82 Precisely as the one who inherits Moses’ mediatory role in the Pentateuch, then, “Aaron, the chief priest, is the messiah.”83

[Page 110]The high priest alone is הכהן המשׁיח hakkōhēn hammāšîaḥ (cf. Leviticus 4.3, 5, 16; 6.22). We turn now to consider the primary purpose of that anointing.

B. Who Shall Ascend the Mountain of Yhwh?

The tabernacle, immediately dominating the literary landscape and encircled by the tribes of Israel, constituted sacred space, guarded by the Levites so that anyone who did not belong to the priestly families and who attempted entrance was subject to the death penalty: “any outsider who encroaches shall be put to the death” (Numbers 3.10, 38).84 Its three zones of intensifying holiness (outer courtyard, holy place, Holy of Holies) corresponded respectively to the mountain of God’s base, midsection, and peak, a symbolism naturally generating the question of who may approach (ascend). Only those ordained may draw near to God (Numbers 16.5, 9, 10; 17.5; Leviticus 21.17).85 Significant to the gate liturgy theme already developed with reference to Moses and Mount Sinai, especially given our consideration of “door” (פתח) and its relation to the gate liturgy in previous chapters, the presentation of the ordination of Aaron and his sons in Leviticus 8-9 “is focused spatially on the door of the tent of meeting (Leviticus 8.3, 33). Indeed, the entire seven day period of the priests’ ordination is a time when Aaron and his sons are to remain at the door of the tent.”86 The essence of the priestly role, then, was access to the Presence, as evident by the vocabulary used to describe such movement: קרב ,נגשׁ ,עמד along with phrases in relation to Yhwh that utilize the prepositional form לפני, and with priests being defined as: הנגשׁים אל-יהוה (“the ones who draw near to Yhwh,” Exodus 19.22), קרובים ליהוה (“those who approach Yhwh,” Ezekiel 42.13; cf. 43.19; Leviticus 10.3).87 Thus, while uncertainty remains concerning the original meaning of the word translated “priest,” the suggestion, widely accepted by scholars, that כהן ḵōhēn derives from the verb כון (“to stand”), so that the priest is defined as one who stands before the divine Presence, appears plausible.88 This is, of course, especially the case with the high priest whose “special status emerges from the entire structure of the priestly cult according to which only the High Priest may minister inside the tent of meeting, before the ark, whereas ordinary priests may officiate only outside the tent,”89 that is, his special status emerges from his being the sole ascender to the (typological) mount’s summit, the “who” in the question: “Who may ascend the mount of Yhwh?”

The focus of Israel’s cultic calendar was upon entering the Holy of Holies, after elaborate preparations (Leviticus 16.2-17), one day out of [Page 111]the year, the Day of Atonement, a privilege granted the high priest alone90 — his “most critical role.”91 Indeed, this annual ritual of penetrating into the divine Presence may be considered the archetypal priestly act,92 whereupon Adam-like he fulfills the cosmogonic pattern:

Once a year on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, Adam’s eastward expulsion from the Garden is reversed when the high priest travels west past the consuming fire of the sacrifice and the purifying water of the laver, through the veil woven with images of cherubim. Thus, he returns to the original point of creation, where he pours out the atoning blood of the sacrifice, reestablishing the covenant relationship with God.93

Significantly, then, in the consecration of the priesthood, only Aaron is anointed (Exodus 29.7; cf. Leviticus 8.12), his anointing constituting a “gesture of approach” with particular reference to the gate liturgy.94 “Priestly unction was a rite of passage to a new status and effected passage from the outer, profane world to the sanctity of the tabernacle precinct.”95 Even for the high priest, however, this privileged entrance was permissible merely one day a year and by measured obedience alone.96 The Day of Atonement narrative begins, in fact, with the command for Aaron not to enter (at just anytime), and this command is itself bracketed by a threefold mention of death — that of his sons (for having approached in an unauthorized manner) and the prospect of his own (for doing likewise, cf. 16.13):

Yhwh spoke to Moses after the death (מות) of the two sons of Aaron, when they drew near (קרב) before the face of Yhwh and died (וימתו). Thus Yhwh said to Moses, “Speak to Aaron your brother that he not enter (אל־יבא) at just any time into the holy place within the veil…lest he die (לא ימות). – Leviticus 16.1-2

Furthermore, only as representative of the renewed humanity—as a new Adam, were Aaron and his descendants permitted access to the cultic mount of Yhwh:

Speak to Aaron, saying, “Any man of your seed in their generations, if he has a blemish, shall not draw near to bring near (לא יקרב להקריב) the bread of his God. For any man who has a blemish shall not draw near (לא יקרב): a man blind or lame, who has a mutilated face or any limb too long, or a man with a broken foot or broken hand, or is a hunchbank or dwarf, or a man with a defect in his eye, or scaled skin or scab, or is [Page 112]a eunuch. Any man with a blemish of the seed of Aaron the priest shall not approach to bring near (לא יגשׁ להקריב) the fire offerings of Yhwh. He has a blemish—he shall not approach to bring near (לא יגשׁ להקריב) the bread of his God. – Leviticus 21.17-21

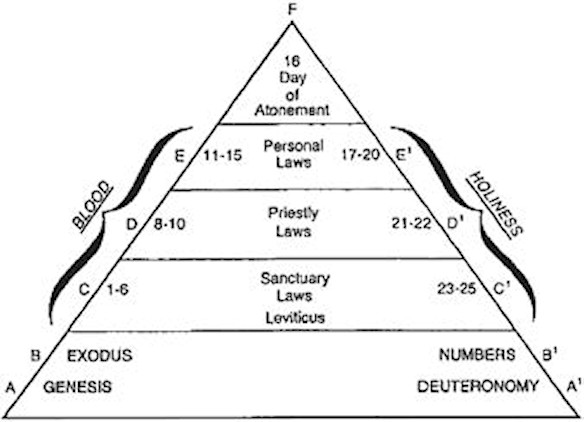

Returning to the Day of Atonement, the weight of this annual drama (and thus of the gate liturgy itself) is manifest by its literary centrality: Leviticus is the center of the Torah,97 and atonement is the central theme of Leviticus,98 with its own center, chapter 16,99 highlighting the Day of Atonement chiastically:100

| FRAME: “And Yhwh said to Moses…” (16.1) | ||||||||||

| A. Aaron should not go into Holy of Holies any time he wishes (16.2) | ||||||||||

| B. Aaron’s sacrificial victims, special vestment (16.3-4) | ||||||||||

| C. Sacrificial victims provided by people (16.5) | ||||||||||

| D. Aaron’s bull, goat for sin-offering, goat for Azazel (16.6-10) | ||||||||||

| A. Genesis | E. Aaron sacrifices bull (16.11-14) | |||||||||

| B. Exodus | F. Goat sacrificed as sin-offering (16.15) | |||||||||

| X. Leviticus – chapter 16 → | X. Atonement (16.16-20a) | |||||||||

| B.’ Numbers | F.’ Goat sent to wilderness (16.20b-22) | |||||||||

| A.’ Deuteronomy | E.’ Aaron’s closing activities (16.23-25) | |||||||||

| D.’ Goat for Azazel, Aaron’s bull, goat for sin-offering (16.26-28) | ||||||||||

| C.’ People rest and humble themselves (16.29-31) | ||||||||||

| B.’ Anointed priest officiates wearing special garments (16.32-33) | ||||||||||

| A.’ Anointed priest makes atonement once a year (16.34) | ||||||||||

| FRAME: As Yhwh commanded Moses…” (16.34) | ||||||||||

In the drama of liturgy, the Day of Atonement was the “most intimate of the representations of access” to the divine Presence.101 Indeed, the importance of this day to the theology of the cult cannot be overestimated:

The goal of the Torah is holiness, which can be symbolically achieved in the cult. This occurs properly through atonement. The act of dedication to God, by which the distance from what is holy is symbolically bridged by the substitutionary offering of blood, is so central for the cult of the Priestly Document, that not only is the great day of atonement the highest holy day, but also every sacrifice takes on the nature of atonement, for it is only atonement, not offering a gift, that can express the meaning of the cult.102

Given the concentric structure of the Pentateuch, with the central book of Leviticus being organized as something of a literary tour of the tabernacle so that the reader, in the footsteps of the high priest, [Page 113]penetrates into the holiest,103 then it becomes apparent that the height of the gate liturgy — the concern for who may approach the divine Presence (and how) — has been reached within the tabernacle Holy of Holies in Leviticus 16, the cultic peak of Yhwh’s mount which extends outward to the literary edges of the Pentateuch. Subsuming meaning from the surrounding narratives, the Day of Atonement also exerts a centrifugal force upon the rest of the Torah. R. M. Davidson’s diagram illustrates the architectural centrality of this once-per- year mythic event of approaching the divine Presence:104

Figure 2: Diagram of Leviticus

This most intimate approach to the divine Presence, moreover, begins with the ceremonial washing of the high priest (Leviticus 16. ורחץ במים את־בשׂרו), likely via the laver (cf. Leviticus 8.6-9; Exodus 30.17-21), thus fulfilling the cosmogonic pattern: through the waters (laver) → to the summit of Yhwh’s mountain (Holy of Holies) → for worship (with cultic atonement signifying the highest gesture of worship). Viewing the Day of Atonement rite as a particularly cosmogonic ritual, what is more, fits logically with its position within Israel’s cultic year. While the completion of the tabernacle, as a new “creation,” resonates with the New Year, the Day of Atonement ritual has also been associated with the New Year,105 often compared to the Babylonian akitu festival.106 This correspondence with the New Year appears sound, furthermore, inasmuch as the Day of Atonement ritual functions to renew the cosmos, seeking “both to address and repair the breakdown in divinely established distinctions of holy/profane, pure/impure, and order/chaos,” and thus sustains and reclaims the divine intention for the created order.107 In priestly theology, [Page 114]“liturgy realizes and extends creation through human reenactment of cosmogonic events.”108

Finally, the gate liturgy theme continues to run as an undercurrent throughout the book of Numbers, particularly evident in chapters 16-17, with the focus having shifted from mountain to tabernacle and from Moses to Aaron, precisely in relation to the latter’s role as high priest. Here three episodes take place, the third being a symbolic reenactment of the previous events, to vindicate not merely “the exclusive right of the Levites to draw near to God” as commentators widely acknowledge,109 but the special prerogative of Aaron to draw near within the holiest as the appointed high priest. Wenham provides an exceptional summary:110

In the first of these [episodes] the non-Levites and Levites try to usurp the priestly prerogatives of Aaron’s family and offer incense within the tabernacle and die in divine judgment (chapter 16). In the second story a plague breaks out and Aaron saves the nation by offering incense (17.1-15). The first set of traditions about Korah, Dathan and Abiram shows the special status of Aaron in a negative way, by relating what happens to those who usurp his prerogatives. The second gives a positive demonstration of his effective mediation making atonement for the people’s sin.

The third story, culminating with the budding of Aaron’s rod, symbolically reenacts the previous narratives. Wenham provides four lines of reasoning to demonstrate this: (1) the Hebrew word מטה maṭṭeh means both “tribe” and “rod”; (2) the names of the tribes are written on the rods illustrating that the latter represent the former; (3) the rods are deposited in the tent of meeting before the testimony, in the divine Presence, paralleling the instructions given previously to Korah and his company (16.16); (4) the demonstration of Aaron’s unique status takes two days, just as for the previous two trials.111 Thus there are

three consecutive tales each making much the same point: that only Aaron and his tribe have a right to draw near to God. … Aaron’s rod was put back “before the testimony,” symbolically confirming that he alone has the right to draw near to God (17.25, cf. 16.5, 17.5). Once the symbolic equation of the rods with the tribes has been noted, other features in the story are clarified. When the rods are removed from the tent of meeting, they show no signs of life. Their deadness symbolizes the death that will overtake these tribes if they attempt to enter God’s [Page 115]presence. Hence their outcry to Moses, “Behold, we perish, we are undone, we are all undone. Everyone who comes near… to the tabernacle of the Lord, shall die. Are we all to perish?” (v 27-28). These verses form the climax to the story of Aaron’s rod.112

Significantly, the almond blossom of Aaron’s rod also has relevance to the gate liturgy, and the Day of Atonement:

[Almond trees] blossom early, which may explain their name, šāqēḏ, “watcher” … It was the duty of the priests and Levites to guard the nation spiritually, by teaching the people of Israel and keeping trespassers out of the tabernacle (Leviticus 10.11; Numbers 3-4). Finally almond blossom is white. In many cultures white symbolizes goodness, purity, authority and divinity. In Israel white linen was worn by the high priest when he entered the Holy of Holies on the day of atonement (Leviticus 16.4).113

These stories, in sum, clearly catechize Israel regarding who may and who may not approach the divine Presence. That is, their meaning unfolds within the context of cosmic mountain ideology and the cultic question of the gate liturgy: “Who shall ascend the mountain of Yhwh?” Indeed, and independently confirming our study, Nihan, who believes P’s narrative culminates with the Day of Atonement, writes: “The gradual restitution of the divine presence in Israel’s sanctuary is thus structured on the model of an ancient Near Eastern ritual of temple entrance, which finds its climax in the great ceremony of Leviticus 16.”114

Thus far, then, we have traced the evolution of the gate liturgy as a symbol: cosmogonic pattern (Genesis 1-3) → cosmogonic + redemptive/eschatological pattern (Genesis 6-9) → micro-cosmogonic + redemptive/eschatological pattern (Exodus 14-24) → ultimately, to the cultic pattern (Leviticus 16), which subsumes the cosmogonic and redemptive/eschatological significance even while lending them a liturgical context. The shift to the cultic pattern follows Yhwh’s cloud of glory as it descends from the height of Mount Sinai upon the tabernacle Holy of Holies, to which movement we now turn.

III. TO DWELL IN THE DIVINE PRESENCE

The biblical-theological goal and dénouement of the narrative arc from Genesis 1-3 to Exodus 40 may be surmised from the descent of the glory [Page 116]cloud upon the tabernacle. Justly does Rodriguez mark Exodus 25.8 as a key text, the divine command forming a link between the first twenty-four chapters of Exodus and the final fifteen: “And let them make me [Yhwh] a sanctuary, that I may dwell in their midst.”115 The tabernacle cultus perpetuates the purpose and goal of the exodus deliverance, first fulfilled at the foot of Sinai: worship, variously described as “sacrifice”/זבח (Exodus 3.18; 5.3; 8.27-29; 10.25); “celebrate a festival”/חגג (Exodus 5.1; 8.20; 10.9); “serve,” “worship”/עבד

(3.12; 4.23; 7.16; 8.1, 20; 9.1, 13; 10.3, 7, 8, 11, 24, 26; 12.31).116 Indeed, this was the sign given Moses: “When you have brought forth the people from Egypt you [pl.] will worship God upon this mountain” (3.12). As the archetype of the tabernacle,117 Mount Sinai—the eschatological experience of being delivered through the waters and brought to the mountain of God for worship — would thus be prolonged and maintained via the tabernacle cultus.118 As cosmic mountain, furthermore, Sinai’s summit corresponds to Eden, paradisiacal features and symbolism also being subsumed by the tabernacle. The key link here is that the תבנית is “a model of the cosmic Tabernacle of Yahweh,” with “the earthly shrine as a microcosm of the cosmic shrine.”119 Thus returning to Exodus 25.8, we find the divine intention clearly expressed as “to dwell/tabernacle” (שׁכן)120 amidst his people. It is a sound suggestion, then, that the cultic mediation of the Presence of Yhwh via the tabernacle has been in view in the Torah’s narrative ever since that Presence was lost with the exile out of paradise in Genesis 1-3, informing the tabernacle symbolism found therein.

The central plot of the story of Exodus 19-40 being “dedicated to the divine movement from mountain to tent,”121 the book of Exodus thus ends with a climax that may serve as something of a bookend with the creation account in as much as it describes a completed temple-building project sanctified by the presence of Yhwh (40.34-35):

Then the cloud covered the tabernacle of meeting, and the glory of Yhwh filled the tabernacle.

And Moses was not able to enter the tabernacle of meeting, because the cloud rested above it, and the glory of Yhwh filled the tabernacle.

The cloud and Presence of glory,122 that is, “the visible manifestation of the divine Presence, not a substitute for it,”123 having rested atop Mount Sinai now moves upon the tabernacle, the building project that is both a proclamation of Yhwh’s cosmic rule and something of an “incarnation” of the triumphant King amidst his vassals.124 As Buber has it, the כבוד is [Page 117]that “fiery ‘weight’ or ‘majesty’ of God radiating from the invisible, which now ‘fills’ again and again the ‘dwelling’ of the tent (40.34), just as it had ‘taken dwelling’ upon the mount (24.16).”125 In this profound gesture, the God of the Patriarchs, El Shaddai, becomes the God of the sons of Israel, of the nation of Israel, to be worshiped corporately through the tabernacle cultus alone.126

The story of chapters 19-40 as a whole, framed by 19.3 and Leviticus 1.1, “presents how the locus of theophany was changed from mountain to tabernacle.”127

This transference and transformation, it may be argued, moves literarily via three steps: (1) establishing the God of creation as the God of the Patriarchs through the narratives of Genesis; (2) establishing the God of the Patriarchs as the God who calls Moses (Exodus 3.6, Yhwh declares: “I am the God of your father — the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob”; cf. Exodus 15.2);128 (3) the glory cloud’s moving from the cosmic mountain (religion of the Patriarchs) to the tabernacle (cultus of Israel).129 That there appears to be deliberate narrative intention to demonstrate continuity between the cosmic mountain religion of the forefathers and the tabernacle/temple cultus of the original audience seems beyond question — and our suggestion, that the creation, deluge, and exodus narratives “pre-figure” the tabernacle cultus, thereby follows as well. Moses’ “mountain experience” in Exodus 24 will thus become the community’s via the tabernacle:

At first, the encounter is reserved for Moses. But the central significance of the Sinai narrative is to demonstrate how this encounter is made transferable, so that it can happen for the whole congregation. Therefore Moses, within the fire, receives the model for the sanctuary, which undoubtedly is heaven itself, the place where God’s own glory shines forth. Therefore the tent of meeting is built, and the cloud of God’s presence moves from Sinai, the world mountain, into the sanctuary, where it is possible for all to encounter God in cultic praise.130

After being tutored in Moses’ ability to ascend, the utterly unexpected statement in 40.35 that he is “not able (לא־יכל) … to enter (לבוא)” is indeed remarkable. In Exodus 33.20, Yhwh had prohibited Moses from entering his Presence too directly (“You are not able (לא תוכל) to see my face…”), so that the prohibition here would seem to imply that Yhwh’s Presence via the tabernacle though mediated is nonetheless a real Presence not to be trifled with — the tabernacle, in other words, provides [Page 118]for Yhwh’s immanence while safeguarding his transcendence,131 with the ritual divine Presence becoming “the highest form of religiosity.”132 The tabernacle thus becomes the one locus in all the earth for God’s Presence to dwell, and the intensity of this glorious mystery is so powerful, Moses is not able to enter.133 Brisman expresses the sublimity of the account well:

Here the sense of God as beyond human activity is troped as the presence of God before human activity: Filling that Tabernacle, God prevents (“goes before” and thwarts) Moses from filling his duty. It is a happy prevention, this dedicatory vision of the presence of God. … For the Priestly writer to conclude Exodus with a vision of God filling the Tabernacle, he needs to look beyond the priestly business of God’s work to a vision of the Divine Presence that prevents and overwhelms the priesthood — and even Moses himself.134

More to the point, with Yhwh’s descent upon the tabernacle, the new cosmos has been sanctified by his Presence. While there is a new creation, however, as yet there is no new humanity — a dramatic tension to be remedied in Leviticus 1-9, as Aaron is consecrated to be the new Adam, approaching the divine Presence via divinely sanctioned sacrifices.135

As the cloud descends upon the tabernacle, God entering his dwelling place and filling it with the כבוד, the book’s end not only forms a counterpart to the deus absconditus of the opening chapters of Exodus,136 although Yhwh’s “filling” (מלא) the tabernacle (40.34, 35) forms an inclusio with the sons of Israel “filling” (מלא) the land of Egypt (1.7),137 but also a bookend with the prologue to the Torah, the creation account of Genesis 1-2.3, where upon completing the cosmic temple, God enters his dwelling place in the enthronement of the Sabbath.138 It might even be said that the creation begun in Genesis 1 comes to fulfillment, however partial, with the establishment of the tabernacle cultus.139 Moreover, the re-creation account of the deluge is also fulfilled by the tabernacle climax of Exodus since the “arrival of the Israelites at Sinai sets in motion acts of atonement, administered by a sanctified priesthood, which will provide the antidote to the pollution, which causes the flood.”140 The tabernacle was “raised” (הוקם), what’s more, on “the first day of the first month” (40.2, 17), the same day the covering was removed from the ark for Noah to gaze upon a renewed creation (Genesis 8.13), that is, on New Year’s Day.141 This new beginning marks the creation (בראשׁית Genesis 1.1), deluge (בראשׁון Genesis 8.13), and tabernacle (40.17 הראשׁון) narratives. The undercurrent of these accounts, the drama and telos of the biblical [Page 119]narrative, particularly as it culminates in the tabernacle story, is the gaining of life in the Presence of the Creator:

[T]he tent located in the heart of the camp was first and foremost a place where the Glory of God was constantly present. God appeared in the cloud above the cherub covering that rested on the ark of the Pact: “for I appear in the cloud over the cover” (Leviticus 16.2). Consequently, the Tent of Meeting was called a tabernacle משׁכן (from the root שׁכן ‘to dwell’), because it was the fixed dwelling place of the Divine Glory. The constant presence of the Glory in the Tent is expressed in the cult of the fixed daily offering (תמיד), in whose framework the priests offered the daily burnt offering, burned the incense, lit the eternal light, and arranged the showbread on the table. Only the perpetual presence of God’s glory within the Tent of Meeting can explain the complex of acts performed in the daily worship.142

The period from the expulsion from paradise until Sinai had been marked by God’s dealings with humanity “from afar.”143 Now, so the message of the tabernacle narrative, the divine Presence is “not merely on an ethereal, cosmic plane” (lost through the expulsion), but is “historically present to Israel.”144 Similarly, Nihan writes:

Yahweh’s return, eventually reported in Exodus 40.34, corresponds to the restitution of the divine presence in Israel after the Flood; the significance of this event is highlighted by the various inclusions with the creation account in Genesis 1. This device, with its mythical background, indicates that in Israel’s sanctuary, as a space set apart from the profane world and as a “model” (תבנית) of the divine palace, the order initially devised by God at the creation of the world can now be partly realized. … Accordingly, it is in Israel’s sanctuary, specifically, that the creator God has chosen to dwell (Exodus 25.8-9; 29.45-46; 40.34) and where, therefore, he can be permanently encountered (root יעד, see especially Exodus 25.22 and 29.43), as in the creation before the Flood. Conversely, this means that it is Israel’s cult which guarantees the permanence of the divine Presence, and hence the stability of the cosmic order.145

The Presence of Yhwh among his people, then, is a — perhaps, the — major theme of Exodus, and indeed of biblical theology.146 The book of [Page 120]Exodus may be traced according to the movement of the divine Presence, as Moshe Greenberg had already noted in 1969:

It is possible to epitomize the entire story of Exodus in the movement of the fiery manifestation of the divine presence. At first the fire burned momentarily in a bush on the sacred mountain, as God announced his plan to redeem Israel; later it appeared for months in the sight of all Israel as God descended on the mountain to conclude his covenant with the redeemed; finally it rested permanently on the tent-sanctuary, as God’s presence settled there. The book thus recounts the stages in the descent of the divine presence to take up its abode for the first time among one of the peoples of the earth.147

Ending where Genesis had begun,148 the book of Exodus marks the historic cultic return to the lost Presence of the Creator, the tabernacle mediating paradise to the exiled descendants of Adam.149 Israel thus becomes a “microcosm of life in creation as God originally intended it,” lived worshipfully in the Presence of God dwelling in — or, perhaps better, “incarnated” through — the tabernacle, “a kind of material ‘body’ for God.”150 Because this crescendo at the end of Exodus also provides the dénouement for the beginning of the Exodus narrative,151 the theme of slavery and liberation is taken up into the understanding of the cultus: true freedom is the life of worship where Yhwh is in the midst of his people.

In sum, the “encounter with God at Sinai represents the beginning of legitimate cultic worship,”152 the beginning of humanity’s return through the gates of Yhwh’s holy mount, and thus a “foretaste of the final joys of life in the Presence of God”153 — this, then, is what the tabernacle cultus signifies as the cultic mountain of God.

CONCLUSION

We have seen how the cosmic mountain, as expressed through historical mounts in the narrative of the Pentateuch, gave way to the tabernacle cultus informed by it: the כבוד moved from Sinai to the tabernacle, the three part structure of the tabernacle corresponding to the three parts of the mountain with the Holy of Holies representing the clouded summit. As the peaks of Sinai and the Ararat mount had echoed Eden in their respective narratives, so the Holy of Holies corresponds to Eden and the blessing of the divine Presence, and the high priest portrays Adam (/Noah/Moses). Thus the narrative arc from Genesis 1-3 to Exodus 40 [Page 121]may be traced as the expulsion from the divine Presence to the gained re-entry into the divine Presence via the tabernacle cultus, from the profound descent of Adam to the dramatic “ascent” of the high priest into the Holy of Holies, particularly on the Day of Atonement.154

This chapter has been adapted from L. Michael Morales, The Tabernacle Pre-Figured: Cosmic Mountain Ideology in Genesis and Exodus (Biblical Tools and Studies 15, Leuven, The Netherlands: Peeters, 2012) 245-277.

Go here to leave your thoughts on “The Tabernacle: Mountain of God in the Cultus of Israel.”