[Page 57]An earlier version of the following paper was presented 5 August 2010 at a conference sponsored by FAIR, the Foundation for Apologetic Information and Research (now FairMormon). The text of this paper is copyrighted by Royal Skousen. The photographs that appear in this paper are also protected by copyright. Photographs of the original manuscript are provided courtesy of David Hawkinson and Robert Espinosa and are reproduced here by permission of the Wilford Wood Foundation. Photographs of the printer’s manuscript are provided courtesy of Nevin Skousen and are reproduced here by permission of the Community of Christ. The text of the Yale edition of The Book of Mormon: The Earliest Text (2009) is copyrighted by Royal Skousen; Yale University Press holds the rights to reproduce this text.

In this paper I discuss the work of the Book of Mormon critical text project and the attempt to restore and publish the original text of the Book of Mormon. I’ve been working on the critical text project from 1988 up to the present, and thus far ten books have been published as part of this project.

Major Findings of the Critical Text Project

There are two main goals in this critical text project. The first is to restore by scholarly means, to the extent possible, the original English-language text of the Book of Mormon. This original language text is, I believe, what Joseph Smith received [Page 58]through a physical instrument – either the Nephite interpreters (later called the Urim and Thummim) or the seer stone – and read off to scribes. The second goal of the critical text project is to determine the history of the Book of Mormon text, in particular the kind of changes that it has undergone, both accidental and editorial. Most of the editorial changes have been of a grammatical nature.

The largest part of the work in recovering the original text involves two manuscripts. The most important of these is the original manuscript (O), the one that Joseph Smith dictated to his scribes. The other manuscript is called the printer’s manuscript (P), and it is a copy of the original manuscript. This second manuscript is the one that was prepared to take to the Palymra, New York, printer E. B. Grandin in 1829-30 to set the type. In addition to the two manuscripts, I have considered 20 printed editions of the Book of Mormon in the critical text project: 15 LDS editions, one private edition from 1858 (the Wright edition), and four RLDS editions (the RLDS Church is now known as the Community of Christ).

Approximately 28 percent of the original manuscript is extant. (In calculating this percentage, I exclude the 116 pages that were lost by Martin Harris in 1828.) In 1841 Joseph Smith placed the original manuscript in the cornerstone of the Nauvoo House, a hotel being built in Nauvoo. The manuscript lay there in the cornerstone for the next 41 years until in 1882 Lewis Bidamon, the second husband of Emma Smith’s, after her death, retrieved the manuscript. Most of it was severely damaged by water that had seeped in; much of it had been eaten away by mold.

Bidamon gave most of the larger manuscript portions to LDS people. As a result, 25 of that 28 percent has ended up in the archives of the LDS Church. The LDS portions cover from 1 Nephi 2 to 2 Nephi 1, from Alma 22 to Alma 60, and from Alma 62 to Helaman 3, and include other minor fragments. [Page 59]There is also half a leaf at the University of Utah (from 1 Nephi 14). And the equivalent of a leaf in fragments is held privately (from Alma 58 to Alma 60).

Of great importance for this project has been the discovery of two percent of the text that Wilford Wood, a collector from Bountiful, Utah, bought from Charles Bidamon, the son of Lewis Bidamon, in 1937. The majority of the Wilford Wood fragments are found in three parts of the text: from 2 Nephi 5 to Enos 1, from Helaman 13 to 3 Nephi 4, and from Ether 3 to Ether 15.

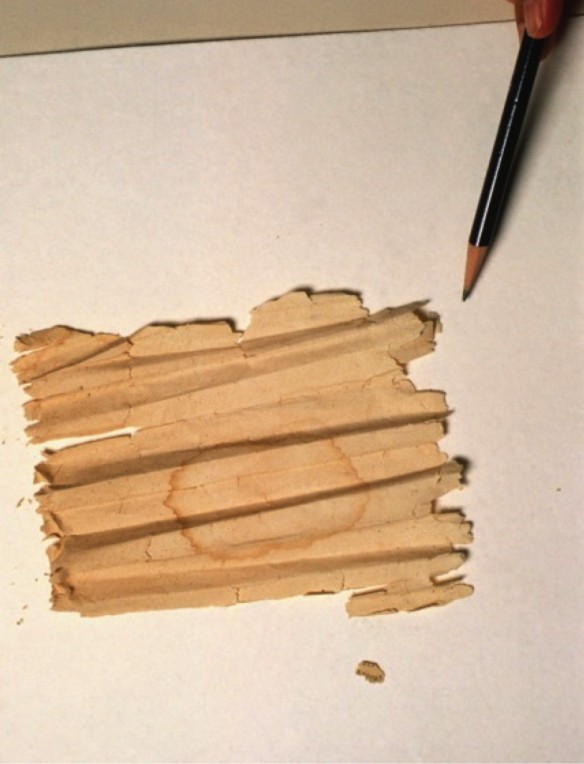

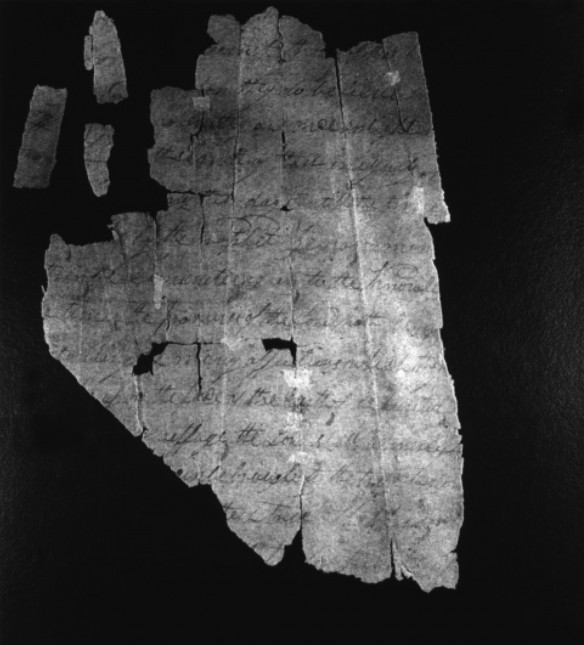

We will now have a look at some of the Wilford Wood fragments. We begin with the lump of fragments as they were observed on 30 September 1991, at the beginning of the conservation of these fragments:

At the time we couldn’t be sure if this really was the original manuscript, or what it might be. But it turned out, for the most part, to be from the original manuscript of the Book of Mormon.

Next we see Robert Espinosa, then the head of conservation at BYU’s Harold B. Lee Library, beginning the very difficult task of teasing apart these fragments:

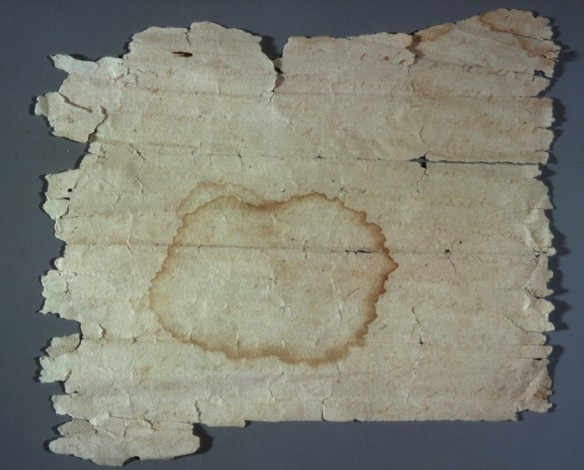

Now consider one of the more interesting fragments found in this lump. This is how it appeared when first removed from the lump, all rolled up:

After it was unraveled, we could see the uneven edges where mold had eaten away parts of the leaf:

In addition, there was a large water stain in the center of the fragment, resulting from the water that had gotten into the cornerstone.

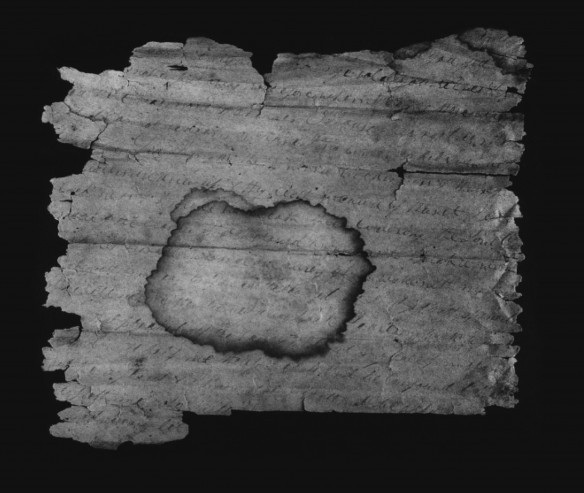

After the fragment was leveled and photographed, we could basically see what was there:

[Page 62]The text for this fragment is in the hand of Oliver Cowdery; the ink was originally black and has turned brown over time. We found that black and white ultraviolet photography brought out the text best of all:

This fragment of the original manuscript comes from 2 Nephi 7-8. When Oliver copied this particular portion of the text into the printer’s manuscript, he made six changes, of which five were accidental. For this part of the text, he was copying an Isaiah quotation, which is difficult enough. Even so, the relatively high number of errors for this single page was unusual for Oliver; he was probably getting tired as he was making the copy here. But it also turns out that he made one conscious change here, a grammatical one, when he changed they dieth to they die as he copied the text into the printer’s manuscript.

[Page 63]One of the biggest discoveries of the critical text project was to find that for one sixth of the Book of Mormon text the printer’s manuscript was not the manuscript taken to the 1830 printer; instead it was the original manuscript. And we can see this quite well from the pencil marks in this color photograph of the original manuscript for Helaman 15:9-14:

The pencil marks were placed here by the 1830 typesetter, John Gilbert. About one third of the time Gilbert marked up his manuscript in advance of doing the typesetting. Overall the [Page 64]evidence is that he used the original manuscript from Helaman 13:17 through the end of Mormon.

Here is the black and white ultraviolet photograph for the same part of Helaman 15; as one would expect, the pencil marks don’t show up as well in a black and white photo:

This important finding about the textual transmission means that from Helaman 13:17 to the end of Mormon there are two firsthand copies of the original manuscript. Only a small percentage of the original manuscript is extant for this part of the text. Yet for this part we have two firsthand copies, which basically means that when those two copies – the printer’s manuscript and the 1830 edition – agree, then that’s probably what the original manuscript read. And when they disagree, then one of the readings is probably the correct one. [Page 65]But trying to determine which reading is the correct one is sometimes quite difficult.

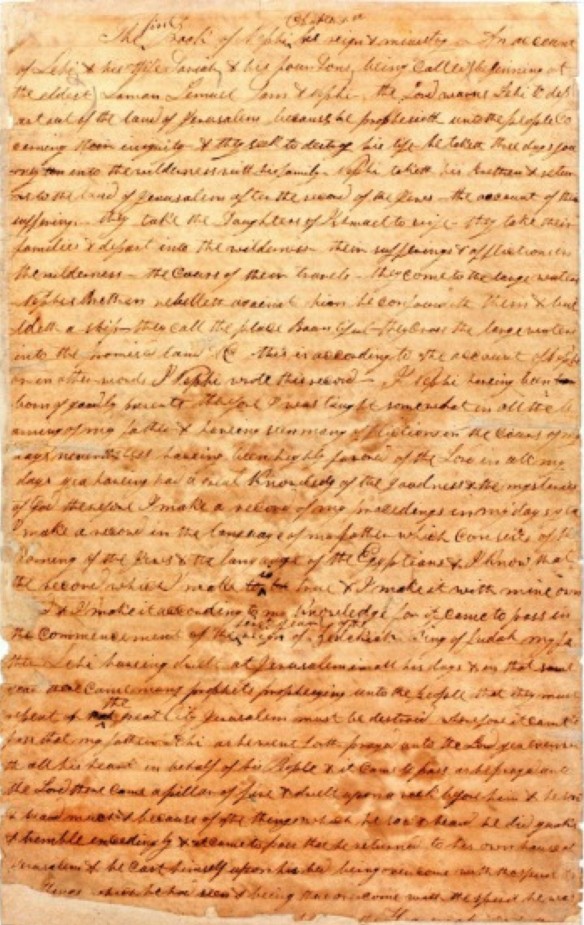

To give you an idea of what the printer’s manuscript looks like, here’s a photo of the first page:

Note that the bottom portion of the first leaf has been worn away; on each side of this leaf, about one and a half lines of text are missing. This page is in Oliver Cowdery’s hand.

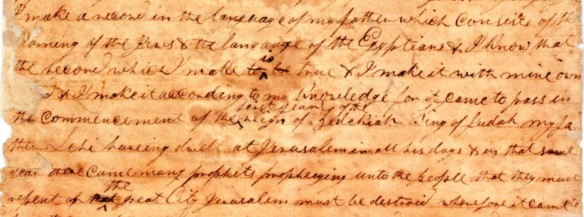

[Page 66]We now turn to a blown-up section from that first page of the printer’s manuscript. For these lines there are a number of corrections:

On the third line, two words, to be, are crossed out. Written above the crossout is a grammatical correction that Joseph Smith made, namely, the word is. Joseph made this change from to be to is (and others like it) when he edited the printer’s manuscript for the second edition of the Book of Mormon (published in 1837 in Kirtland, Ohio). On the next line – you can barely see it – after the word knowledge there is a capital letter P that was added by the 1830 typesetter. It’s above the line, written in pencil, and it tells the typesetter to start a new paragraph at this point.

There are a couple of other corrections here that were made by Oliver Cowdery when he originally wrote down the text for the printer’s manuscript. Sometimes he missed some words or wrote something wrong, which he then corrected, often by inserting words above the line. In the last line shown here, Oliver originally wrote the word that, then he crossed it out and wrote the above the crossout. These kinds of corrections in copywork were frequently made by the original scribe for the printer’s manuscript. And we also find corrections like these in the original manuscript.

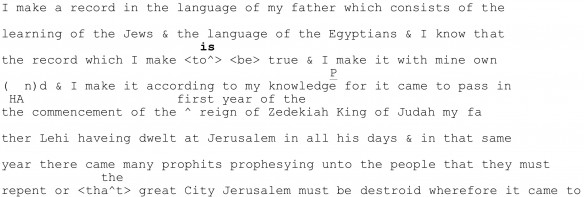

Next we have what is called a facsimile transcript (or typographical facsimile) for this part of the manuscript.  [Page 67]As part of the critical text project of the Book of Mormon, we have produced transcripts like this one in order to faithfully record what’s actually on the manuscripts. Note, for instance, that in this case the word prophets was misspelled as prophits in the next-to-last line. And destroyed was spelled as destroid in the last line. In each instance, we leave it to the reader to figure out what the intended reading is. Most of the time there isn’t any problem.

[Page 67]As part of the critical text project of the Book of Mormon, we have produced transcripts like this one in order to faithfully record what’s actually on the manuscripts. Note, for instance, that in this case the word prophets was misspelled as prophits in the next-to-last line. And destroyed was spelled as destroid in the last line. In each instance, we leave it to the reader to figure out what the intended reading is. Most of the time there isn’t any problem.

In 2001 the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS, now part of the Maxwell Institute at BYU) published the facsimile transcripts of the original and printer’s manuscripts. These two volumes are made up of three large blue books, and they reproduce all the then-known portions of the original manuscript as well as the virtually complete printer’s manuscript. From these books one can read what’s in the actual manuscripts.

Since 2001 I have continued work on three other volumes. Volume 4 was completed in 2009. This volume is called Analysis of Textual Variants of the Book of Mormon. There are six maroon books in that volume. They represent my work on recovering the original text, going from verse to verse, looking at all of the variants (and potential variants) in the text as well as looking at all the textual evidence, in order to determine what the original reading might have been.

Volume 3 is called The History of the Text of the Book of Mormon. This is the volume that I am currently working on. [Page 68]And volume 5 will be a computerized collation that will be made available with volume 3. Later in this paper, we’ll consider what that collation looks like.

The Yale Edition of the Book of Mormon

As I got near the end of completing the six books of volume 4, I discovered some potential problems with the project as originally conceived. One of the problems was in getting people, even some academic people doing research on the Book of Mormon, to cite the findings of the critical text project. These books are very large and heavy; and as a complete set, they are also rather expensive. In any event, the result was that researchers were writing articles on the Book of Mormon but, it would seem, quite oblivious to what the actual reading should be – or at least what the critical text project had to say about the reading.

Another problem that became apparent was that with the completion of volume 4 anyone could go out and produce their own original-language version of the Book of Mormon by simply using the findings of volume 4 and referring to the resulting book as the original text. I decided that it would be better if I myself retained control over this process, and so I arranged with Yale University Press to publish, in August 2009, The Book of Mormon: The Earliest Text. This book represents in one volume the original text, to the extent it can be determined. And if you take off the dust jacket of this book, you will see that the hard cover matches the maroon cover of volume 4. This was done intentionally, to show the connection to volume 4 of the critical text; in other words, the Yale edition derives from the decisions made in volume 4.

There are two important innovations in the Yale edition. The first is that it is set in sense-lines – not in small paragraphs where each verse is its own little paragraph, nor in narrow double columns. My idea, as originally conceived, was to break the [Page 69]lines in the text so that they would represent in some general way how Joseph Smith dictated the text – namely, in phrases and clauses, but none so long that they could not be easily read.

One of the things I have been surprised about since the publication of the Yale edition is how much readers like this format. Many readers, including scholars of the text, have seen things in the text that they have never seen before, simply because it is laid out in sense-lines. Nor do readers get fatigued as they do when reading a two-column text that frequently breaks in the middle of words (by hyphenation) or in the middle of phrases and clauses, a process that puts a lot of stress on readers in negotiating the text. With the sense-lines, it’s also much easier to keep on reading. Some readers have discovered they now read several chapters at a time instead of just the single chapter they were used to reading.

The second innovative aspect of the Yale text is that it is the first time anyone has attempted to publish the original English-language text, to the extent that it can be determined. The Yale text, it turns out, does not have what we call a copytext. It is not a revision of some particular edition of the Book of Mormon. Instead, everything has been done from scratch, so to speak; in fact, the text is directly derived from the computerized collation, as we shall see.

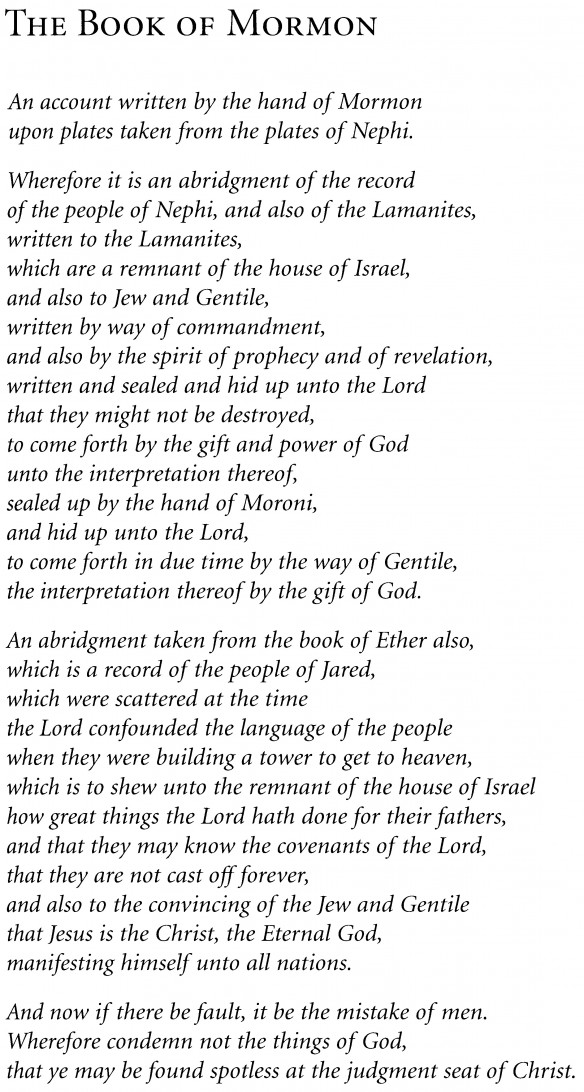

Below we see the title page of the Yale edition and of the Book of Mormon itself. The line breaks occur at places where you could reasonably pause, especially if you were reading the text off to someone else, as in dictation. You will note, by the way, that the traditional statement about the book being translated by Joseph Smith is not on the Book of Mormon title page. That’s because it wasn’t on the original title page of the Book of Mormon. Instead, I place that attribution on the preceding page, on what we call the half title. This is the appropriate place to acknowledge Joseph Smith as the translator.

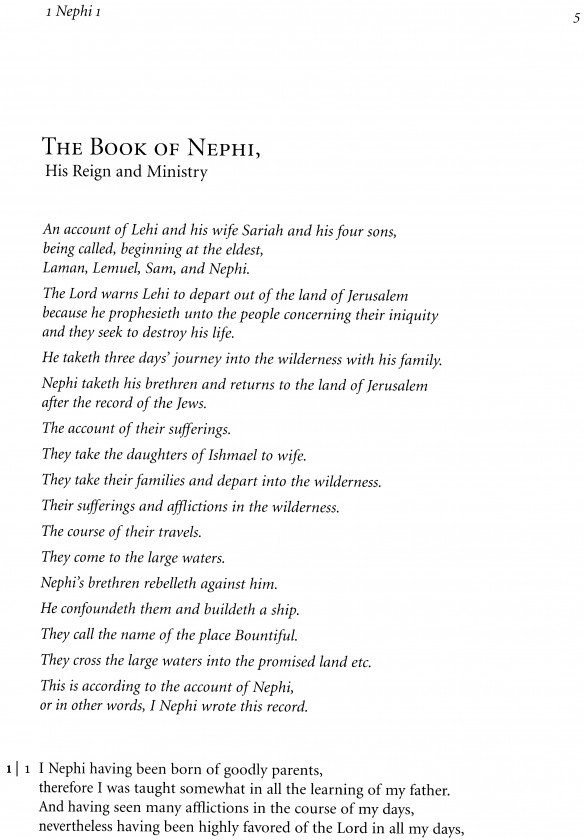

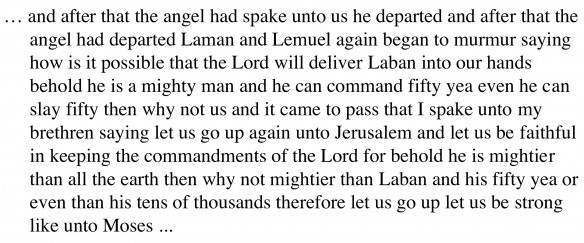

Next is the beginning of First Nephi. You’ll notice that the text just says “The Book of Nephi” – that’s because the manuscripts tell us that that was the original title for the book. There are, it turns out, four books of Nephi in the Book of Mormon. Later Oliver Cowdery and other editors added first, second, third, and fourth to the names of these individual books. The original text had no numbers for any of the books of Nephi. Since this is the way the original text read, we reproduce it that way in the Yale edition.

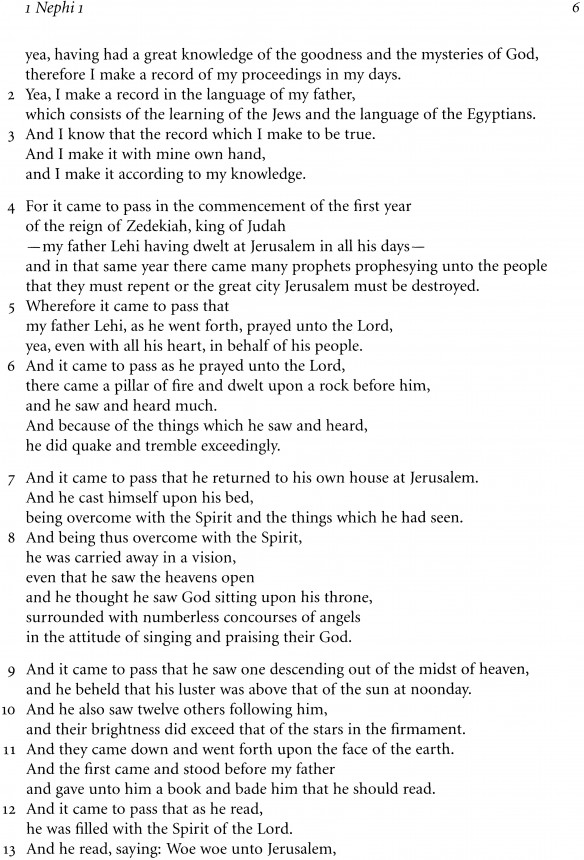

On the following page of the Yale edition you can clearly see the sense-lines. There are also extra lines of space that represent the paragraphs that I have broken the text into. You will note that overall this is a clear text, a plain text. There is not much editorial intrusion beyond the sense-lines and the paragraph breaks, although I did put the LDS chapter and verse [Page 71]

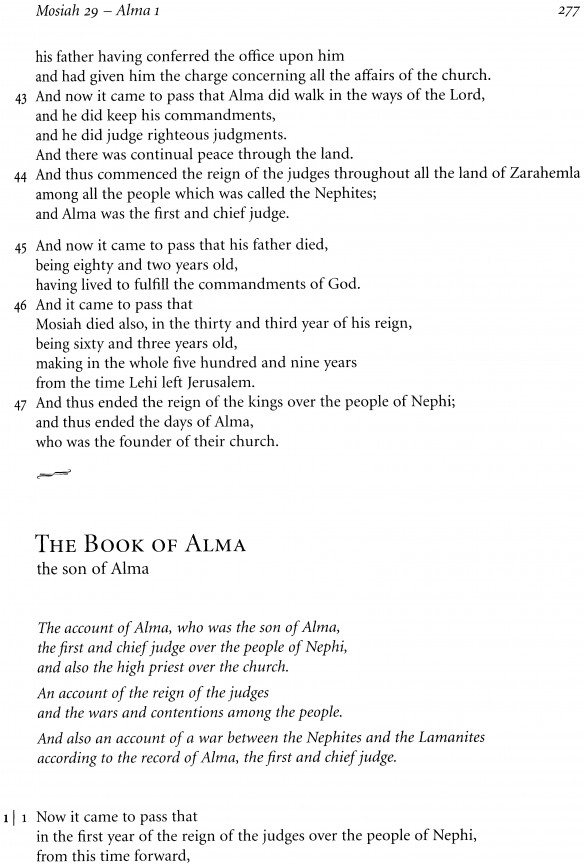

numbers out in the left margin because readers need to reference where they are in the book. At the top of the next page you can see how the Yale edition shows a transition from one book to another, namely, from Mosiah to Alma.

numbers out in the left margin because readers need to reference where they are in the book. At the top of the next page you can see how the Yale edition shows a transition from one book to another, namely, from Mosiah to Alma.

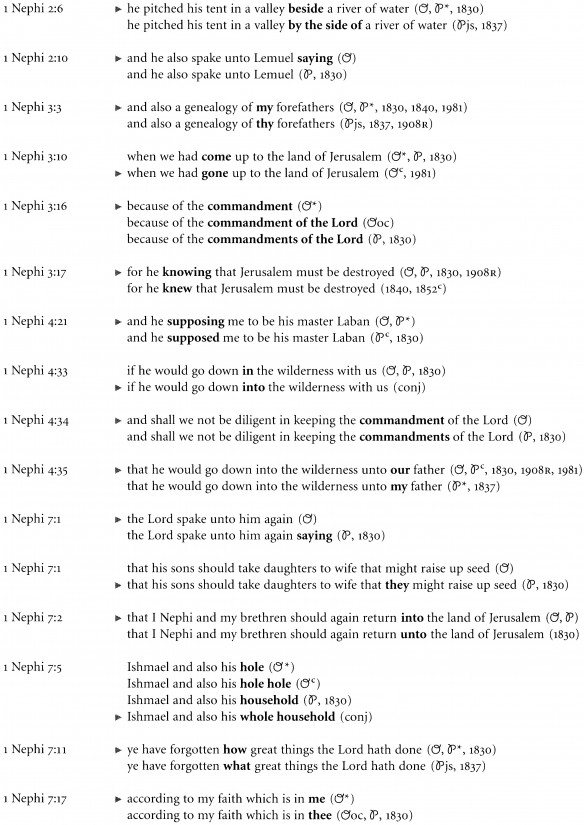

As mentioned earlier, the Yale text was not derived from a copytext (that is, from a particular edition of the Book of Mormon) but instead from a computerized collation that gives all the textual variants. At the bottom of the next page, for instance, is the computerized collation for that portion of 1 Nephi as it goes from chapter 3 to chapter 4.

At the beginning of each line of this collation, before each textual variant, there is some indication in braces (that is, in curly brackets) of the kind of variant that will follow. Then in square brackets I give the actual variant. The very first variant in this sample from the collation is a number – in fact, it’s a verse number. The two manuscripts are represented by the symbols 0 and 1; and since the manuscripts don’t have any verse numbers, there is in this case no number assigned to the original and printer’s manuscripts. In the rest of the textual [Page 72]

[Page 73]variant we find the capital letters A through T, which stand for the printed editions of the Book of Mormon (from the 1830 edition to the 1981 edition). In this instance, the majority of the printed editions have a verse number (but the particular number varies). You can go down through the collation and consider in the same way each variant in turn.

[Page 73]variant we find the capital letters A through T, which stand for the printed editions of the Book of Mormon (from the 1830 edition to the 1981 edition). In this instance, the majority of the printed editions have a verse number (but the particular number varies). You can go down through the collation and consider in the same way each variant in turn.

The underlined text in the collation represents what I believe is the original text (but with the spelling we expect in today’s standard English). The text in bold stands for the reading of the original manuscript. In other portions of the collation (not shown here), you won’t find any bolding; that means that the original manuscript is not extant for those portions.

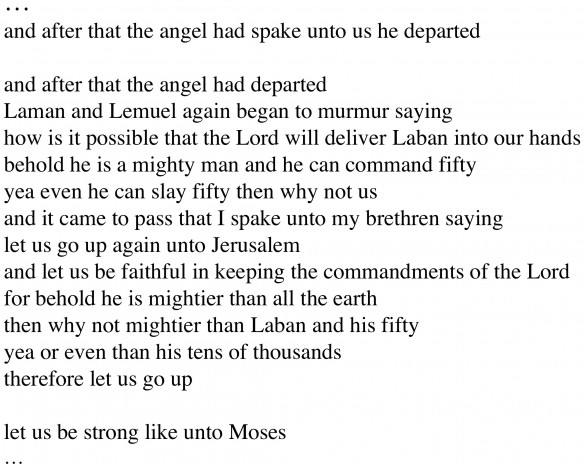

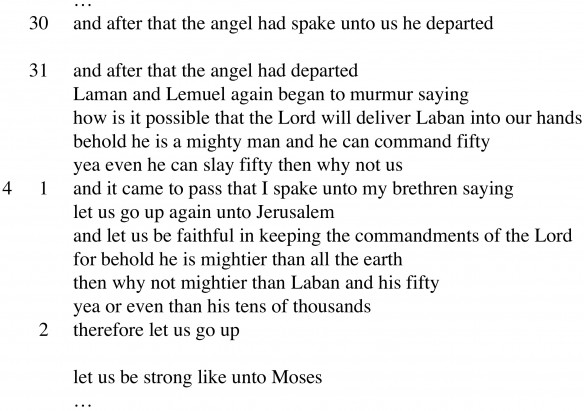

With the help of my colleague Deryle Lonsdale, a computer program was used to extract the underlined text from the computerized collation. This means that I did not key in the text for the Yale edition. Here is what you get when you extract the underlined text for that portion of the collation covering the transition between 1 Nephi 3 and 4:

This is the proposed original text for this passage, but without any intended line breaks (that is, hard returns) or punctuation. This is much like what the 1830 typesetter was confronted with when he set the type – a long string of words with no breaks except when a new chapter begins.

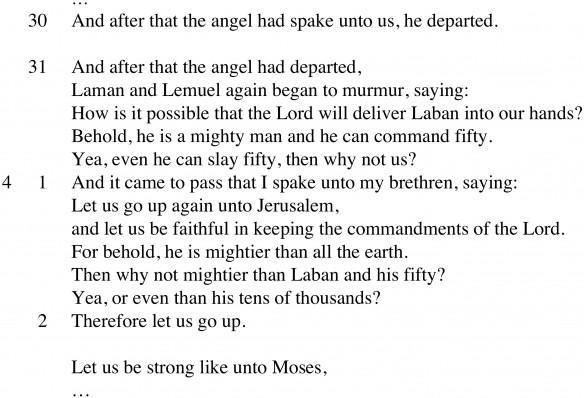

From this long string of words, I then constructed the sense-lines and put extra lines in for where I thought there should be paragraph breaks:

In the next stage, I added the LDS chapter and verse numbers in the left margin:

One of the things you’ll notice here is that chapter 4 comes in the middle of a paragraph. Reading this portion of the text, one sees that there probably shouldn’t be a chapter break, not even a paragraph break, where chapter 4 begins.

And finally, after the chapter and verse numbers had been added, I put in the punctuation (as well as the necessary capitalization), but from scratch, without looking at the original [Page 75]1830 punctuation or the current punctuation (which derives from the 1830 edition):

I found this last task to be the most difficult one in preparing the Yale edition. I’m frankly amazed of what John Gilbert, the 1830 typesetter, was able to do here, especially given the difficult syntactic structure of the Book of Mormon. It appears that for about two thirds of the text Gilbert determined the punctuation as he set the type. He did a really fine job, although he probably overpunctuated the text from our modern point of view (but this is what was expected in his day). What I wanted to do here was to determine anew the punctuation for the entire text. As far as I know, the Yale edition represents only the second time that the punctuation has been done completely from scratch – at least in a published edition.

The Yale edition also has an appendix that shows the significant changes in the text. There are 719 of these at the end of the book. In the Yale edition, I wanted the list of changes to appear in the appendix, not intruding upon the text itself. I should also point out that this appendix is not simply a comparison between the current standard LDS text and the Yale edition. Instead, it’s a representation of important changes that have occurred in the history of the text. In many instances, the [Page 76]Yale edition agrees with the current text. The appendix is not intended to be a listing of differences, but rather of significant variants in the history of the text.

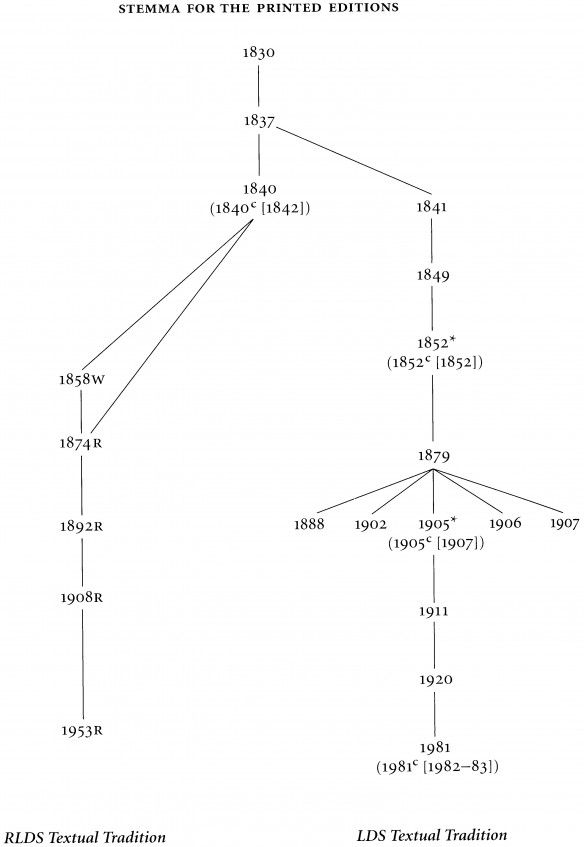

At the beginning of the appendix there is a stemma that shows the textual relationship between the printed editions of the Book of Mormon:

You will notice here that there are two textual traditions that split off from the second edition (the 1837 Kirtland edition). One is the RLDS textual tradition – that’s on the left. And on the right is the LDS textual tradition. These stemma relationships show the copytext for each printed edition from 1830 on. If you consider, for instance, the 1920 LDS edition, the stemma shows that its copytext was the 1911 LDS edition. This means that the 1920 typesetter worked off a copy of the 1911 edition, one that was presumably marked up with changes. In other words, the stemma here shows the copytext relationships between the various editions.

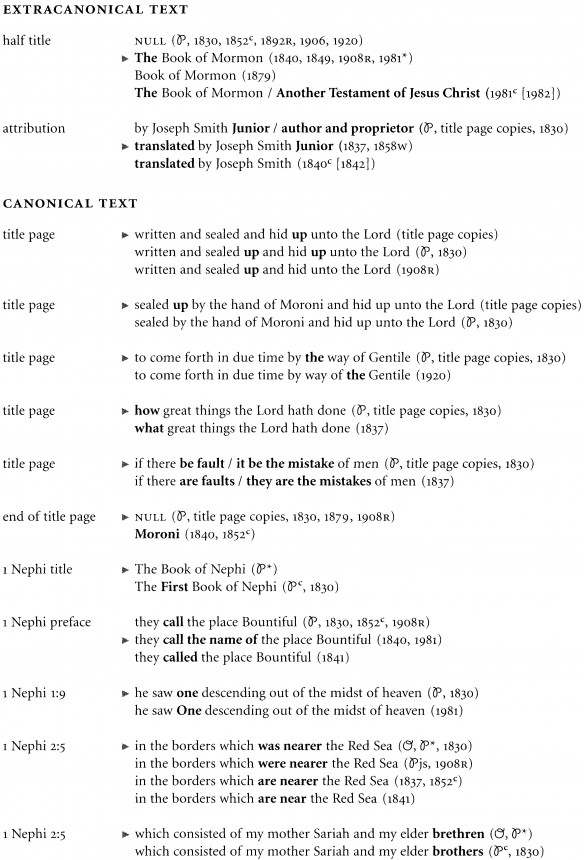

[Page 77]Now let us turn to the actual list of the 719 significant textual changes.

For each set of alternative readings, I indicate with a pointer the one I have accepted as the original reading. For each case, I always list the reading of the original manuscript, if it exists, plus the reading of the printer’s manuscript and the reading in the 1830 edition. I then list any other edition that deviates from its copytext – that is, any place where the editors or typesetters for that edition decided on some other reading, either an earlier one or perhaps a new conjecture. And so you can actually reconstruct the whole history in each case, providing you refer to the stemma that shows the copytext relationships for the editions.

[Page 78]Here’s the second page of the list of significant changes:

The Yale edition, as already noted, derives from volume 4 of the critical text. In volume 4 there are 5,280 cases of variation that I considered. It turns out that 2,241 of these differences show up in the Yale edition. This last count, I should point out, excludes most cases of grammatical variation in the text. Nor is this number particularly important because most of these changes aren’t earthshaking.

However, there are a couple of numerical counts that are important. One is that there are 606 changes in the Yale edition which have never appeared in any standard printed edition of the Book of Mormon, in neither the LDS nor the RLDS textual traditions. And if you look at those readings that account for [Page 79]the number 606, you will see that the vast majority come from the manuscripts:

216 from O

88 from both O and P

2 from copies of the title page

187 from only P (in cases where O is not extant)

113 conjectural emendations

Over half of the new readings (304 of them) come from the original manuscript. And 187 come from the printer’s manuscript (these are cases where the original manuscript is not extant). There are also two new readings in the title page that come from other early copies of that page. None of these 493 readings have ever been implemented in any of the standard printed editions. In addition, there are 113 conjectures. I will come back to conjectures in a moment.

What is important to note here is the significance of the original manuscript in restoring the original text. For the six books of volume 4 of the critical text, I recently went through the 491 new readings that come from the two manuscripts and I divided them up according to which book in volume 4 they are discussed. For three of the books (the first, fourth, and fifth), large portions of the original manuscript are extant (each of these books is marked below with an asterisk). And for each of those books, consider the number of new changes that show up:

| O | P | both | ||

| *1 Nephi 1 – 2 Nephi 10 | 95 | 6 | 38 | |

| 2 Nephi 11 – Mosiah 16 | 2 | 34 | 5 | |

| Mosiah 17 – Alma 20 | 0 | 58 | 3 | |

| *Alma 21 – Alma 55 | 93 | 12 | 28 | |

| *Alma 56 – 3 Nephi 18 | 25 | 50 | 13 | |

| 3 Nephi 19 – Moroni 10 | 1 | 27 | 1 |

For the first and the fourth book, about 75 percent of the original manuscript is extant, and we get almost 100 new changes for both of these books. For the fifth book, about 25 percent of [Page 80]the original manuscript is extant, and we get a proportional amount of new changes. For the three other books of volume 4, we have hardly anything of the original manuscript, and it shows. What this really means is that by human endeavor we aren’t going to recover as much of the original text for these parts of the text. It makes a real difference when we don’t have the original manuscript.

A second numerical count that is quite important is that the Yale edition introduces 241 new readings that make a difference in meaning. By the phrase “difference in meaning” I mean that if we translate the reading into another language there will be a change in the words – that is, there will be some word difference, no matter what the language. For each of these 241 readings, the change makes a difference in meaning, not just in phraseology.

A good example of this kind of meaning change is found in 1 Nephi 12:18, which reads as follows in the original manuscript: “and a great and a terrible gulf divideth them / yea even the sword of the justice of the Eternal God”. But Oliver Cowdery miscopied this into the printer’s manuscript as “yea even the word of the justice of the Eternal God”. In other words, Oliver replaced sword with word. And that’s the reading that’s been retained in the text ever since. Yet when we look at the rest of the Book of Mormon, we discover that there are seven references to “the sword of God’s justice” but no examples of “the word of God’s justice”:

| Alma 26:19 | the sword of his justice | |

| Alma 60:29 | the sword of justice | |

| Helaman 13:5 | the sword of justice (2 times) | |

| 3 Nephi 20:20 | the sword of my justice | |

| 3 Nephi 29:4 | the sword of his justice | |

| Ether 8:23 | the sword of the justice of the Eternal God |

In particular, note that the example in Ether 8:23 (“the sword of the justice of the Eternal God”) is identical to the original [Page 81]reading in 1 Nephi 12:18. In considering the translation of this change in words, I know of no language where sword and word are the same word. Every translation is going to end up making the change here. This is what I mean then by a change in meaning. Of course, this change doesn’t make a huge difference in meaning. To be sure, one can accept a reference to God’s justice being enacted by his word. But that isn’t what the text originally read in 1 Nephi 12:18. It read sword.

Some people have asked whether any textual restoration ever alters doctrine – and the answer is, no. Whenever a change involves doctrine, we find that the original reading has the correct doctrine. An example of this is found in Alma 39:13, where Alma is talking to his son Corianton and tells him to go back to the Zoramites and, in the original manuscript, “acknowledge your faults and repair that wrong which ye have done”. When Oliver Cowdery finished writing this page in the original manuscript, he accidentally dropped some ink on the page. And on the letter p in repair a drop of ink fell right on top of the ascender for the p, which ended up making the p look like it’s been crossed. In fact, the p ends up looking like a t. Moreover, Oliver’s r‘s and n‘s often look alike, so when Oliver came to copy this part of the text into the printer’s manuscript, he copied it as “acknowledge your faults and retain that wrong which ye have done”. That reading doesn’t quite work, and so the 1920 LDS committee decided to just remove the word retain because it didn’t make any sense. Thus they ended up having Alma say to Corianton that he should go back and “acknowledge your faults and that wrong which ye have done”. In other words, “go back and say you’re sorry”. But the need for Corianton to repair his wrong had now been removed from this passage.

When we look at other parts of the Book of Mormon text, we indeed find that when people confess their sins, they do everything they can to repair the wrongs or the injuries they [Page 82]have done. Here’s one from Mosiah 27:35: “zealously striving to repair all the injuries which they had done to the church / confessing all their sins”. And here’s one from Helaman 5:17: “they came forth and did confess their sins … and immediately returned to the Nephites to endeavor to repair unto them the wrongs which they had done”. So by putting back the word repair in Alma 39:13, the correct doctrine of repentance is restored. The doctrine hasn’t been changed.

In the Yale edition you will also find 15 new readings for Book of Mormon names. For me, the most interesting one is that the actual name for the surviving son of king Zedekiah was Muloch, not Mulek, the implication being that Zedekiah named this son after the pagan god Moloch that they sacrificed children to, thus suggesting a rather ominous aspect to king Zedekiah’s character.

Conjectural Emendations in the Text

I pointed out above that the Yale edition has 113 new conjectural emendations, and some people have been critical of this. But I think it’s worth noting that in every printed edition of the Book of Mormon there are numerous readings that are the result of conjectural emendation. A conjecture is introduced into the text whenever a typesetter, a scribe, or an editor doesn’t like the particular reading of his copytext and doesn’t like any of the other readings that might have appeared in earlier editions or in the manuscripts, and so he decides on a new reading. That’s a conjecture. (Here I exclude emendations involving grammatical editing.)

What we find in the history of the Book of Mormon text is that conjectures have been quite common, and in many instances they are necessary. Sometimes the original manuscript has such a bad reading that no one is going to accept it. Consider, for instance, the reading of the original manuscript in 1 Nephi 7:5: “the Lord did soften the heart of Ishmael and [Page 83]also his hole hole“. That’s the way the original manuscript reads, hole hole. In fact, this is the corrected reading in the original manuscript, which means that that is what that scribe, probably one of the Whitmers, finally decided on. When Oliver Cowdery copied this passage into the printer’s manuscript, he just couldn’t accept the reading of the original manuscript. He decided that hole hole was household, thus writing in the printer’s manuscript “the Lord did soften the heart of Ishmael and also his household”. My conjecture, on the other hand, is that the original text here actually read “the Lord did soften the heart of Ishmael and also his whole household“. That would explain why the original manuscript ended up having two instances of hole, one standing for whole, the other for the hold of household.

In support of this reading, consider the rest of the text of the Book of Mormon: whenever a passage refers to a patriarch and his household, the text always refers to his entire household. In corresponding contexts, we have either “all his household” or “his whole household” (the latter reading occurs in Alma 22:23). The ultimate point here is that in 1 Nephi 7:5 one can’t accept the reading of the original manuscript, hole hole. There must be a conjecture here, either household or whole household (or perhaps some other possibility). For that phrase, every text of the Book of Mormon is going to have to read as some kind of conjecture.

When we look at the current standard text, we find that there are 654 conjectured readings. On the other hand, there are 354 in the Yale edition. It turns out that the Yale edition accepts a lot of difficult readings that have otherwise been removed over time from the standard text. In volume 4 of the critical text, I considered 1,346 cases of conjectural emendation. About one fourth of them (26 percent) were accepted. It’s also worth noting that when we compare the Yale edition with the current standard text there are 187 conjectures that both [Page 84]texts agree on. So there is considerable agreement in conjectures between the two texts in addition to the differences.

It’s also instructive to consider the individuals who have had the most influence in introducing conjectural emendations into the text. Oliver Cowdery, the main scribe for both manuscripts, made 131 conjectures, of which the Yale edition accepts about 30 percent. For instance, in 1 Nephi 7:1 the original manuscript reads: “that his sons should take daughters to wife that might raise up seed”. When Oliver copied this into the printer’s manuscript, he added the pronoun they, thus “that his sons should take daughters to wife that they might raise up seed”. In volume 4 of the critical text, I provide the arguments for why I think the pronoun they was in the original text. By the way, you won’t find that discussion in the Yale edition, although the change is listed in the appendix. The arguments are all in volume 4 of the critical text.

On the other hand, here is one of Oliver Cowdery’s conjectural emendations that I think he got wrong. In 1 Nephi 13:24 the original manuscript reads “it contained the fullness of the gospel of the Land“, which seems impossible. When Oliver copied this passage into the printer’s manuscript, he changed “the gospel of the Land” to “the gospel of the Lord“. He obviously couldn’t accept the word land here, and he thought Land looked like Lord. In actuality, the reading of the original text was very likely “the gospel of the Lamb“. The original scribe apparently misheard lamb as land but without the d at the end being pronounced, which he then wrote as Land in the original manuscript. At every other place in the Book of Mormon (namely, in four places in 1 Nephi 13), the text consistently reads “the gospel of the Lamb“, never “the gospel of the Lord“. Of course, “the gospel of the Lord” is possible, but that isn’t the way the Book of Mormon expresses it.

John Gilbert, the typesetter for the 1830 edition, made a total of 167 conjectures, of which a large percentage, 47 [Page 85]percent, are accepted in the Yale edition. The reason so many are accepted is that in many cases Gilbert was confronted with a manuscript reading that was unacceptable yet it was easy enough to figure out the correct reading. That’s why the percentage of acceptance is so high for him. Here’s an example from 1 Nephi 17:48 where I think he was right. His manuscript copy read “and whoso shall lay their hands upon me shall wither even as a dried weed“. Gilbert interpreted the word weed as an error for reed, and thus he set the text as “even as a dried reed“.

On the other hand, in Alma 5:35 Gilbert replaced the verb put with hewn, giving “and ye shall not be hewn down and cast into the fire” rather than “and ye shall not be put down and cast into the fire”, the reading of the printer’s manuscript. Normally the Book of Mormon text refers to people being hewn down and cast into the fire. Even so, the occurrence of put down was more likely an error for the visually similar cut down, so that the original text (and original manuscript, not extant here) probably read “and ye shall not be cut down and cast into the fire”. The word cut was likely written with a capital C in the original manuscript, with the result that the scribe who copied the text into the printer’s manuscript misread the capital C as a capital P, thus introducing put as the verb.

Joseph Smith made a large number of conjectures (198 of them) in his editing for the second edition of the Book of Mormon (published in 1837). For the third edition (published in 1840), he made 19 more conjectures. In most of these cases, Joseph was simply trying to remove difficult readings from the text. Many of these original, difficult readings are, nonetheless, acceptable. (Only about 16 percent of Joseph Smith’s 1837 conjectures are accepted – and even less for the 1840 conjectures, about 11 percent.) I suspect Joseph often thought “That reading is difficult for people to understand, so let’s change it to this.” For instance, in Ether 3:9 there is a change in the 1837 edition where Joseph correctly inserted the word not, changing “for [Page 86]were it so / ye could not have seen my finger” to “for were it not so / ye could not have seen my finger”. On the other hand, in Mosiah 21:28 Joseph Smith replaced king Benjamin with king Mosiah in order to deal with a perceived problem in chronology. I think, in this case, Joseph’s emendation was unnecessary. You can read the arguments in volume 4.

We can also consider the number of conjectures in the more significant editions since 1840 and identify how many of them are accepted in the Yale edition:

| 1849 | Orson Pratt | 8 | 2 | 25% | |

| 1852 | Franklin and Samuel Richards | 17 | 5 | 29% | |

| 1879 | Orson Pratt | 9 | 4 | 44% | |

| 1905-11 | German Ellsworth | 8 | 2 | 25% | |

| 1920 | James E. Talmage | 130 | 22 | 17% | |

| 1981 | scriptures committee | 10 | 4 | 40% |

Note in particular the high number of conjectural emendations in the 1920 LDS edition, largely the result of James E. Talmage’s determination to emend difficult readings in the text. The large majority of these emendations were unnecessary, although they made the text easier to read. Only about one conjectured reading out of six in the 1920 edition is accepted in the Yale edition.

A number of LDS scriptural scholars have independently made suggested emendations prior to the critical text project. In many respects, these are good suggestions, and a rather high percentage, 48 percent, have been accepted:

| Paul Cheesman | 1 | 1 | |

| Stan Larson | 7 | 3 | |

| Hugh Nibley | 1 | 1 | |

| W. Cleon Skousen | 1 | 1 | |

| Sidney B. Sperry | 3 | 3 | |

| John Tvedtnes | 10 | 2 |

In my work as editor of the critical text project, I have proposed 401 conjectures, 103 of which I have accepted – or 26 percent (about one reading out of four).

Of particular help in this project have been people who have independently sent me suggestions for change or [Page 87]identified readings that seemed strange in some way. In all, 42 individuals have corresponded with me and have recommended 173 changes, of which 36 – or 21 percent (about one out of five) – have been accepted. Thus the Yale edition reflects a tremendous amount of input from careful readers of the text. Here I list eight people who basically went through the whole text of the Book of Mormon looking for readings that seemed problematic: David Calabro, Joanne Case, Lyle Fletcher, Ross Geddes, Heather Hardy, Paul Huntzinger, Brent Kerby, and Greg Wright. You will find their suggestions discussed in volume 4, and in many instances their suggested changes made it into the Yale text.

Word for Word Control over the Original Text

In this last section, I want to mention the evidence that the original text of the Book of Mormon is a precise English-language text, specified word for word, and that when it was given by means of the instrument to Joseph Smith, he could see that text and he read it off to his scribe. B. H. Roberts thought that reading off the text was too easy, but of course B. H. Roberts himself never received a text from the Lord in that way. There’s a lot of evidence that the translated text of the Book of Mormon was controlled down to the very word, in fact, to the very letter (at least for the spelling of Book of Mormon names).

The first type of evidence involves the occurrence of Hebrew-like constructions that are unacceptable in English and have consequently been edited out of the text. One example is the extra use of the conjunction and that follows a subordinate clause and comes right before the main clause. Recently I’ve discovered that these extra and ‘s do not occur if the subordinate clause is simple. They only occur when there is some complexity in the subordinate clause, either an extra clause or a phrase that interrupts the flow of the text. When that happens, [Page 88]the Hebrew-like and usually appears. Here are some examples involving various subordinate conjunctions:

1 Nephi 8:13

and as I cast my eyes around about

that perhaps I might discover my family also

and I beheld a river of water

Helaman 13:28

and because he speaketh flattering words unto you

and he saith that all is well

and then ye will not find no fault with him

3 Nephi 23:8

and when Nephi had brought forth the records

and laid them before him

and he cast his eyes upon them and saith …

Mormon 3:4

and it came to pass that after this tenth year had passed away

making in the whole three hundred and sixty years

from the coming of Christ

and the king of the Lamanites sent an epistle unto me

Moroni 10:4

and if ye shall ask with a sincere heart with real intent

having faith in Christ

and he will manifest the truth of it unto you

by the power of the Holy Ghost

The last example is one of the most famous passages in the Book of Mormon.

All of these extra and‘s have been removed from the Book of Mormon text – and that’s because they are such bad English. But what does the occurrence of these extra and‘s say about the translation? It says that Joseph Smith had to have seen the and‘s. If he had just been getting ideas in his mind, there would have been no reason for him to have put these and‘s in – they’re non-English, and they haven’t occurred in any known dialect of English or in the history of the language. And their occurrence isn’t just an accident since there are so many examples of [Page 89]the extra and. Moreover, there is this wonderful passage from Helaman 12:13-21 where seven of them occur in the original text, virtually one after another, beginning with this one in Helaman 12:13:

yea and if he saith unto the earth

move

and it is moved

These extra Hebrew-like and‘s were really there. Joseph could see them, and so he read them off.

Another type of evidence, one even more surprising (and controversial to some) is that the meanings of the words in the Book of Mormon come from the 1500s and 1600s. To be sure, there are examples of archaic Book of Mormon word usage that can also be found in the 1611 King James Bible, such as the phrase “to cast an arrow”, which means ‘to shoot an arrow’. This is found in Alma 49:4: “the Lamanites could not cast their stones and their arrows at them”. But we also find that expression in the King James Bible, in Proverbs 26:18: “as a mad man who casteth firebrands arrows and death”.

Another example that also occurs in the King James Bible is the verb require with the meaning ‘to request’. In Enos 1:18 the Book of Mormon text reads “thy fathers have also required of me this thing” – in other words, Enos’s fathers requested this thing of the Lord. Similarly, in the King James Bible, in Ezra 8:22, Ezra refrains from requesting troops from the Persian king: “for I was ashamed to require of the king a band of soldiers and horsemen to help us against the enemy in the way”.

A third example is the use of the verb wrap with the meaning ‘to roll’, in 3 Nephi 26:3: “and the earth should be wrapped together as a scroll”. Compare this with the usage in 2 Kings 2:8: “and Elijah took his mantle and wrapped it together and smote the waters”.

[Page 90]All of these meanings can be found in the Oxford English Dictionary (referred to as the OED). For each of the three verbs already mentioned, their archaic meanings were typical of 1600s language and can therefore be found in the King James Bible. And one could argue, then, that they are in the Book of Mormon simply because Joseph Smith knew his Bible that well.

The problem with this proposal is that there is archaic 1500s and 1600s usage in the Book of Mormon text that is not found in the King James Bible. Consider the original occurrence of the conjunctive but if in Mosiah 3:19: “for the natural man is an enemy to God … and will be forever and ever but if he yieldeth to the enticings of the Holy Spirit”. Here but if means ‘unless’, and that meaning occurred in Early Modern English (for this meaning the OED gives citations dating from 1200 to 1596). We have this 1580 example from Sir Philip Sidney: “He did not like that maids should once stir out of their fathers’ houses but if it were to milk a cow.” The editors for the 1920 LDS edition of the Book of Mormon decided to emend the reading in Mosiah 3:19, replacing but if with unless, which is semantically correct and makes the text understandable for modern readers.

Another Book of Mormon example uses the verb commend in a sentence with the meaning ‘to recommend’: “and now I would commend you to seek this Jesus” (Ether 12:41), which in today’s English would read “and now I would recommend you to seek this Jesus”. The OED gives a date in the 1600s for this usage, which has now died out.

Another very interesting example of archaic usage in the original text is the phrase “to counsel someone” with the meaning ‘to counsel with someone’. There are two examples of this usage in the original text (in Alma 37:37 and Alma 39:10), for which the 1920 LDS committee added the preposition with (which is correct as far as the meaning goes). But when we go back to Early Modern English, we get uses of the phrase “to counsel someone” with the meaning ‘to counsel with someone’, [Page 91]as in this 1547 example from John Hooper: “Moses … counseled the Lord and thereupon advised his subjects what was to be done.”

Another example is the original use of the verb depart with the meaning ‘to part, divide, or separate’. This meaning for depart was regularly used in English Bibles up to the 1611 King James Bible. But by then that meaning for depart had become archaic, so the King James translators systematically eliminated that use of depart from their translation, with the result that so there are no examples in the King James Bible of what had regularly occurred in earlier English translations. Yet the Book of Mormon has this particular use of depart in Helaman 8:11 in the printer’s manuscript: “to smite upon the waters of the Red Sea and they departed hither and thither”. The 1830 typesetter just couldn’t believe that departed was correct, so he replaced the word with parted (thus he set “to smite upon the waters of the Red Sea and they parted hither and thither”). We have examples from the 1557 New Testament of the Geneva Bible like “they departed my raiment among them” (John 19:24), translated in the 1611 King James Bible as “they parted my raiment among them”.

In the following example from Helaman 9:17, language usage from the 1500s and 1600s leads us to consider assigning the meaning of ‘to expose’ to the verb detect: “and now behold we will detect this man and he shall confess his fault”. Such usage can be found, for instance, in this example from Richard Hooker in 1594: “The gentlewoman goeth forward and detecteth herself of a crime.”

The adjective extinct now refers to the death of a species, but in Early Modern English it could refer to the death of a person, as we find in a 1675 English translation of Machiavelli’s The Prince: “the Pope being dead and Valentine extinct“. And we find such usage in the original (and current) text of the Book of [Page 92]Mormon: “and inflict the wounds of death in your bodies that ye may become extinct” (Alma 44:7).

Here is an interesting example from Helaman 7:16 where the text uses the verb hurl but it more likely refers to dragging rather than throwing: “yea how could ye have given away to the enticing of him who art seeking to hurl away your souls down to everlasting misery and endless woe”. And the OED provides a 1663 citation from Robert Blair where hurl is assigned the meaning ‘to drag or pull with violence’: “The new creature was assaulted, hurled, and holed as a captive.” And this is what we expect in Helaman 7:16, that Satan will drag us down to hell.

The expression “to pitch battle” no longer exists as such in modern English; today we have it only in the set phrase “a pitched battle”. In fact, we generally think of a pitched battle as an intensively fought one, but originally what it referred to was a fully set battle. Interestingly, the Book of Mormon uses the original, now archaic, syntactic expression in Helaman 1:15: “and they came down again that they might pitch battle against the Nephites”. In Early Modern English there is Christopher Marlowe’s 1590 example in the passive, “Our battle, then, in martial manner pitched.” But such general use of the verb phrase “to pitch battle” no longer exists in English.

Finally, I give an example of an unexpected extension of the noun rebellion in Mosiah 10:6: “and he began to stir his people up in rebellion against my people”. In today’s English, we think of the word rebellion as hierarchical, that rebellion occurs in opposition to higher authority. But this example from the Book of Mormon refers to the Lamanite king as stirring up his people, the Lamanites, against the people of Limhi, a Nephite people that are in virtual slavery to the Lamanites. The meaning of the phrase “in rebellion” in Mosiah 10:6 seems to simply mean ‘in opposition’; there the phrase “in rebellion” lacks any kind of hierarchical implication. Thus far I have found only one example (and an early one at that) with this [Page 93]more general meaning for the noun rebellion (used by Gilbert Haye in 1456, as cited in the OED): “if man should have this rebellion and contrariety, any against another, when they are of diverse complexions?”

The third type of evidence that shows the preciseness of the original text of the Book of Mormon deals with various set expressions and word forms that were consistently used in the original text but are no longer consistent in the standard text. In over a hundred different expressions and word forms, the text has developed various exceptions to its original consistency, exceptions that we might call “wrinkles in the text”. The original translated text is so consistent in this respect that it doesn’t look like it’s the result of a translator freely choosing how he should translate a given expression or word form each time he comes across it. Here are some examples; I first give the numerical count for usage in the current standard text, then in the original text:

whatsoever, never whatever

72 to 2 in the current text; 75 to 0 in the original text

conditions, never condition

12 to 2 in the current text; 14 to 0 in the original text

this time, never these times

60 to 1 in the current text; 61 to 0 in the original text

“observe to keep the commandments”, never “observe the

commandments”

10 to 1 in the current text; 11 to 0 in the original text

“thus ended a period of time”, never “thus endeth a period of time”

43 to 4 in the current text; 47 to 0 in the original text

“to do iniquity“, never “to do iniquities“

21 to 1 in the current text; 22 to 0 in the original text

“if it so be that …”, never “if it be so that …”

36 to 2 in the current text; 38 to 0 in the original text

[Page 94]“to have hope“, never “to have hoped“

17 to 1 in the current text; 18 to 0 in the original text

“the Nephites and the Lamanites”, never “the Nephites and

Lamanites”

14 to 1 in the current text; 15 to 0 in the original text

Thus the original text appears to be a fully controlled text. The Yale edition restores more than one hundred of these kinds of systematic phrases and word choices.

Another type of evidence for the systematic nature of the original text can be found in identical citations that come from completely different parts of the text. One well-known pair of citations involves a reference to Lehi’s vision of the heavenly scene. Originally identified by John W. Welch, this language is first quoted in 1 Nephi 1:8 as “and he thought he saw God sitting upon his throne surrounded with numberless concourses of angels in the attitude of singing and praising their God“, then the same precise language, word for word, is used considerably later, in Alma 36:22: “yea and methought I saw – even as our father Lehi saw – God sitting upon his throne surrounded with numberless concourses of angels in the attitude of singing and praising their God“.

Another example of identical citation involves a liturgical expression found in Mosiah 3:8, which originally read as follows: “and he shall be called Jesus Christ the Son of God / the Father of heaven and of earth / the Creator of all things from the beginning“. Later, in Helaman 14:12, we get the same language, word for word: “and also that ye might know of the coming of Jesus Christ the Son of God / the Father of heaven and of earth / the Creator of all things from the beginning“. Interestingly, in Mosiah 3:8 the 1830 typesetter accidentally deleted the preposition of before the noun earth, giving “the Father of heaven and earth” rather than the correct “the Father of heaven and of earth”. So in the current text these two liturgical citations are no longer identical.

[Page 95]There is also evidence for letter for letter control over the spelling of Book of Mormon names. The witnesses of the translation process indicated that whenever the scribe had difficulty in spelling an unknown name correctly, Joseph Smith would spell it out for him. And we can find clear evidence of the spelling out of Book of Mormon names in the original manuscript. For instance, in Alma 33:15, when Oliver Cowdery had to spell the name Zenoch for the first time in the original manuscript, he initially spelled it as Zenock. Then he immediately crossed out the misspelling, Zenock, and wrote inline the correct spelling, Zenoch. Later on, in Helaman 1:15, Oliver originally spelled the first occurrence of the name Coriantumr as Coriantummer, a phonetic spelling. Again, he crossed out the misspelling and then wrote inline the correct Coriantumr. In this instance, Joseph would have been required to spell out the name letter for letter in order to get the otherwise impossible sequence mr at the end of the name.

Conclusion

There are three goals that have guided me in producing The Book of Mormon: The Earliest Text. First of all, I wanted to present the text in an inviting format and provide a clear text with minimal editorial intrusion, one that would be fully accessible and easy to read – and for both LDS and non-LDS readers. Second, I wanted to publish the most accurate text possible, one with readings based on the two manuscripts and the earliest editions. And finally, I wanted to provide access to all the significant textual changes that the text has undergone over the years, from the manuscripts and early editions up to the current LDS and RLDS editions. But since I did not want these variants to intrude upon the text itself, I placed them in an appendix.

As I have studied the original text and the evidence of how it was transmitted, it’s become very clear to me that this text [Page 96]was revealed to Joseph Smith word for word and that he could actually see the spelled-out English words. We do not know the precise mechanism that allowed Joseph to receive the text in this way, but the evidence argues that the text was a specific English-language translation that was revealed through him. It is indeed a marvelous work and a wonder.

Go here to see the 7 thoughts on ““The Original Text of the Book of Mormon and its Publication by Yale University Press”” or to comment on it.