Abstract: Mack C. Stirling examines the well-known story of Job, one of the literary books of the Bible and part of the Wisdom literature (which is heavy in temple mysticism and symbols), and proposes the story follows the temple endowment to the T. Following Hugh Nibley’s lead in The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri, the temple endowment is not discussed. Stirling focuses only on Job’s story, drawing on analysis of literary genres and literary tools, like chiasms, focusing on the existential questions asked by the ancient author. Doing this, he concludes that Job’s is a story about a spiritual journey, in which two main questions are answered: “(1) Is it worthwhile to worship God for His own sake apart from material gain? (2) Can man, by coming to earth and worshipping God, enter into a process of becoming that allows him to participate in God’s life and being?” What follows is an easy to read exegesis of the Book of Job with these questions in mind, culminating with Job at the veil, speaking with God. Stirling then discusses Job’s journey in terms of Adam’s journey — beginning in a situation of security, going through tribulations, finding the way to God and being admitted into His presence — and shows how this journey is paralleled in Lehi’s dream in the Book of Mormon (which journey ends at a tree of life). This journey also is what each of us faces, from out premortal home with God, to the tribulations of this telestial world, and back to the eternal bliss of Celestial Kingdom, the presence of God, through Christ. In this way, the stories of Adam and Eve, of Job, and of Lehi’s dream provide a framework for every human’s existence.

[Editor’s Note: Part of our book chapter reprint series, this article is reprinted here as a service to the LDS community. Original pagination and page numbers have necessarily changed, otherwise the reprint has the same content as the original.

[Page 138]See Mack C. Stirling, “Job: An LDS Reading,” in Temple Insights: Proceedings of the Interpreter Matthew B. Brown Memorial Conference, “The Temple on Mount Zion,” 22 September 2012, ed. William J. Hamblin and David Rolph Seely (Orem, UT: The Interpreter Foundation; Salt Lake City: Eborn Books, 2014), 99–144. Further information at https://interpreterfoundation.org/books/temple-insights/.]

The book of Job has challenged and puzzled interpreters for centuries. All agree that the beauty and eloquence of its Hebrew poetry are unsurpassed and that Job raises important, penetrating questions not addressed elsewhere in the Bible. Yet the meaning of many phrases and words in the book is simply unknown, which is partly responsible for multiple divergent interpretations. There is no scholarly consensus on the date, author, structure, stages of composition (if any), nature (history, narrative, story, or dramatic fiction), or meaning of the book. Not unexpectedly, no one translation of Job is adequate; meaning and translation are invariably influenced by one’s life experiences and theological presuppositions.1

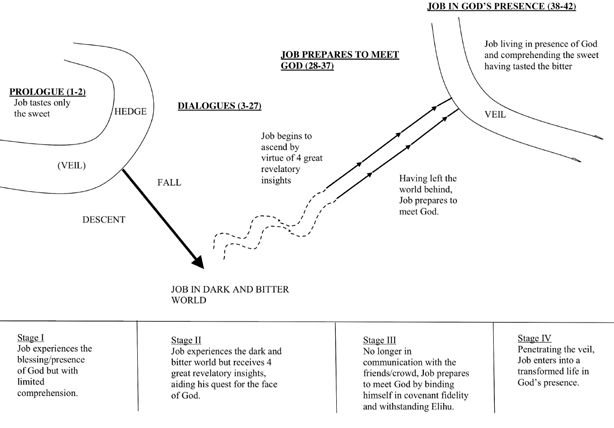

I propose that the book of Job is a literary analogue of the temple endowment ritual. The book’s structure, content, and use of prose versus poetry will be important in presenting my case. Following the lead of Hugh Nibley in his The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri, I will discuss only the book of Job in its literary and scriptural context, leaving the reader to make connections to the endowment.2 An overview of the literary structure of the book of Job is presented in Table 1, demonstrating the scheme followed in this exposition.

Table 1. Literary Outline of Job

B. Second Cycle (Job 15-21)

C. Third Cycle (Job 22-27)

Job becomes increasingly alienated from his community with failure of communication. Job resolves to meet God and receives four great revelatory insights.

B. Elihu Speeches (Job 32-37), poetry except 32: 1-5 (prose)

Whereas Job may well have been a historical figure (see Ezekiel 14:14, 20; James 5:11; Doctrine & Covenants 121:10), the biblical book of Job is, in my view, an extremely sophisticated literary composition designed to raise questions and invite man into a deeper relationship with God. There are many features of Job that strain credulity if the book is approached as literal history, including the quasi-partnership of God and Satan in the Prologue. Likewise, distressed humans are unlikely to converse in beautiful poetry while sitting on an ash heap, as portrayed in the Dialogues (see Job 3–27). The book of Job, like all great drama, uses dialogue (as opposed to narrative) in an attempt to penetrate the essence of things — to explicate important truths about God, man, and their possibilities for covenant relationship.

Job and his three friends start with shared assumptions and a common understanding of the nature of God, man, and the cosmos. They are in confessional unity. This quickly breaks down as Job, as a result of his suffering, begins to question previously shared assumptions.

Most of the disputes in the book of Job are related to the idea of retribution. The friends (and Job initially) conceive of a rigid order in the cosmos, created and maintained by an all-powerful and perfectly just God, where the righteous prosper and the wicked are brought to ruin, after perhaps being given a time to repent. Therefore, they reason, if a person suffers, he or she must have sinned.3 Having previously thought the same, Job comes to know by his bitter suffering that rigid retribution is false. He realizes that he is suffering innocently (suffering out of proportion to any sin), along with many others, whereas the wicked frequently thrive. Job holds ferociously to this truth, destroying the previous unity with his friends. Job is forced to entertain probing questions about the nature of God, man, and the moral order, questions [Page 140]that lead to his transformation. He comes to understand that salvation cannot be adequately encompassed by categories of sin and retribution and that truth is more important than confessional unity based on false premises.

Irony abounds in the book of Job. By irony, I mean a text that is intended to mean something different from what it seems to say. Thus, the important meaning is different from, even contrary to, the superficial or obvious meaning. For example, Job asks, “Who will say to [God], ‘What doest thou?’” (Job 9:12, rsv). Here Job seems to say that no man would venture to question God’s actions. Yet, questioning God is precisely what Job does. As another example, God asks Job, “Where were you when I laid the foundations of the earth?” (Job 38:4, rsv). This appears to portray an overbearing God intimidating Job with His awesome majesty. Ironically, however, God may actually be inviting Job to a deeper understanding of and participation in creation. Superficially, this text seems to suggest that Job could not have been present at creation, whereas ironically he may well have been (Abraham 3:22–25). Irony functions to invite the reader into a creative and profound engagement with the text and to subvert conventional understanding.

Central to my analysis of the book of Job is the concept of the existential question as described by Janzen.4 Existential questions are not posed to be answered by facts or information. They are related to a process of growth and becoming, with the question posing a goal to be lived toward. The answer to the question is the transformed self, it having been given the power to move toward the goal by the question itself. The disclosure of one’s own existential questions to others admits them to the sphere of one’s own being and becoming. To share existential questions is to offer to share being. Janzen views covenant as a relationship in which participants share existential questions toward a shared outcome. In this light, the creation of earth by God for man is a covenantal act wherein God shares existential questions with man: (1) Is it worthwhile to worship God for His own sake apart from material gain? (2) Can man, by coming to earth and worshipping God, enter into a process of becoming that allows him to participate in God’s life and being?

The book of Job can be understood as Job’s spiritual journey in response to questions posed by God. Existential questions arising within God in the Prologue are shared with Job, eventually stripping him of everything dear to him. Job internalizes these questions in his darkened and bitter state during the Dialogues. He holds on, evolving toward a [Page 141]transformed understanding of God and man, and finally reaches God’s presence and experiences redemption. We will now consider Job’s journey in detail.

Prologue (Job 1–2)

Job, whose name potentially means either “Where is the divine father?” or “the persecuted one,”5 is a non-Israelite living in an unnaturally idyllic world. He is rich and healthy, has a large and loving family, and is esteemed as the greatest man of his people. Furthermore, he is a member of a community with strong social bonds, a shared religion, and a common language. Job experiences all of this as the presence and friendship of God (see Job 29:2–7) and responds by living blamelessly, serving his fellow man, and defending the poor (see Job 1:1, 29:11–25). Nonetheless, as subsequent events will demonstrate, Job is, as yet, lacking both in self-knowledge and knowledge of God. He has personally experienced only goodness, tasting only the sweet.

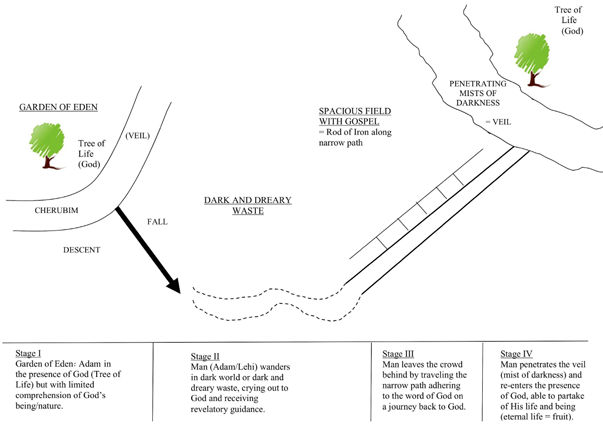

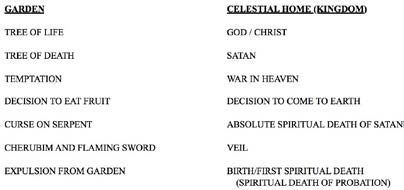

Despite having reproduced and being a member of an established community, Job’s situation in the Prologue is analogous in many ways to that of Adam in the Garden before the Fall. Indeed, I consider the Prologue of Job to be a this-worldly analogue of the Garden of Eden.6 I find it significant that the Prologue is composed in prose and will later make the case that the other two prose sections of Job (32:1–5 and 42:7-17) are also this-worldly analogues of other-worldly situations, events, or people. In contrast, the poetry sections of Job relate directly to events in this mortal, fallen world.

God intrudes on Job’s idyllic life by bringing Job to Satan’s attention, clearly in response to existential questions within God Himself about Job’s character and motivation and about the significance of human worship of God.7 Satan insists that Job fears God only for secondary gain and that he would not worship God “for naught,” introducing the metaphor of the “hedge” to summarize all that God has done to prosper and protect Job (see Job 1:9–10). This hedge around Job is best conceived as a many-layered veil, consisting of the nourishing and cradling conditions of Job’s life: health, family, wealth, societal fabric of shared language and religion, and perceived stable order and justice in the cosmos.8 Satan wagers that if God will tear down the hedge, Job will curse God (see Job 1:11). God gives Satan permission to proceed with dismantling the hedge, stating: “All that he has is in your power” (Job 1:12, rsv).

[Page 142]Job’s response is of utmost importance to God. The question is whether Job will hold fast to his integrity — which, in my view, consists of remaining absolutely honest but continuing to seek a relationship with God despite the loss of the hedge. Failure of integrity would result from yielding to the pressure of the crowd and admitting that his sins justify his suffering, effectively holding on to a lie in hopes of appeasing “God.” Likewise, cursing God and seeking completely autonomously to find his own way in the world would breach his integrity. Either response would be a victory for Satan, the father of lies.

Satan goes out from God, and Job’s hedge begins to collapse. Two different bands of marauding humans destroy some flocks and servants. “Fire from heaven” completes their destruction, while a great wind destroys Job’s children. The book of Job is ambiguous about the precise relationship of either God or Satan to these natural and human-initiated disasters.

After these experiences, Job proclaims that he is “naked” (Job 1:21), like Adam and Eve in the garden after eating the forbidden fruit (see Genesis 3:7–11). Job continues to bless God, so Satan receives permission to afflict Job’s skin with loathsome sores, removing a more interior part of the hedge (Job 1:21–2:7). All that remains of Job’s hedge are the societal bonds of caring friends, shared religion, and common language. These, too, will be stripped away in the ensuing Dialogues, leaving Job alone to struggle with the great moral question of whether he should serve God “for nothing.”

After Job is afflicted with the sores, his wife invites him to “curse God and die,” thus mediating the desire of Satan (Job 1:11, 2:5). In this action she precisely parallels Eve in the garden, who conveyed Satan’s desire to Adam that they eat the forbidden fruit. Job calls his wife foolish and then continues with an apparently rhetorical question: “Shall we receive good at the hand of God and shall we not receive evil?” (Job 2:10, rsv). This response is ambiguous — much different from Job’s blessing of God after the first series of calamities. Job’s irritation at his wife, combined with his hiding behind a seemingly rhetorical question, suggest that his wife has actually expressed an existential question now raging inside Job.0

Job removes himself in solitude to an ash dump, resigning himself to a dreary waste (compare with 1 Nephi 8:4–7), while describing his state in terms of bitterness (see Job 7:11, 9:18, 10:1, 13:26, 23:2, 27:2) and darkness (see Job 16:16, 19:8, 23:17, 30:26). Job has thus gone through a kind of fall, brought about, in some sense, by the machinations of Satan but nonetheless occurring at the initiative of God. The book of [Page 143]Job thereby expresses in a literary, dramatic way the idea that “it must needs be that the devil should tempt the children of men, or they could not be agents unto themselves; for if they never should have bitter they could not know the sweet” (D&C 29:36). Just like Adam and Eve, Job has partaken of the bitter tree, which will make it possible for him to comprehend the sweet tree or tree of life (compare with 2 Nephi 2:15–16) and thus partake of the life and being of God. Participating in God’s life is much different than simply being taken care of by God.

In general, the sources of suffering (tasting the bitter) in this world are personal sin, the sins of others, natural disasters, and ignorance. We know from the Prologue that Job’s suffering is innocent, not the result of personal sin, although this will subsequently be disputed ever more vociferously by the “friends.” As mentioned above, the Prologue seems to imply that both God and Satan had a role in causing Job’s suffering, with the text being ambiguous about the precise level of responsibility of each. Even when Satan supposedly goes out to afflict Job, the text speaks of “fire from God” (Job 1:16). Furthermore, when we look directly at Job’s suffering, it is caused either by the sins of other humans or natural disasters, all exacerbated by Job’s relative ignorance. Such suffering, which Job experiences to an extreme degree, is part and parcel of life in this created, risky world, which is filled with people who voluntarily abuse others and which is subject to unpredictable natural events. I argue that the book of Job gives no definitive answers to the reasons for innocent suffering. The very ambiguity of the book on these points invites the reader to ponder and question.10

My opinion that the book of Job is a dramatic literary composition and not literal history is supported by the extreme nature and the stylized reporting of the first series of disasters to befall Job. In all four instances one person “alone escapes to tell” Job. Additionally, the very ambiguity regarding the source of each disaster (God? Satan? nature? humans?) fits drama more than literal history. Furthermore, God’s complaining to Satan that Satan had “moved [God] against [Job] to destroy him without cause” (Job 2:3, rsv) strains credulity beyond reason if taken as history. Finally, I doubt that the true God would literally authorize the massacre of a man’s children simply to put him to the test.

The book of Job is not primarily about suffering. It is about a journey from blissful ignorance through darkness and bitterness to a transformed relationship with God. It is about seeking an ever stronger connection to God, based on truth, no matter what the circumstances. Job’s journey is initiated by God in response to existential questions within God. The [Page 144]existential questions are then taken up by Job as a result of his suffering as he is driven to wonder what it means to be created in the image of God, why innocent suffering occurs, and what God’s relationship is to justice. In this process, Job is proved and tried at God’s initiative, much like all humanity: “We will go down, for there is space there, and we will take of these materials and we will make an earth whereon these may dwell; and we will prove them herewith, to see if they will do all things whatsoever the Lord their God shall command them” (Abraham 3:24–25).

The tearing down of Job’s hedge can be understood as passing through a veil — passing from a protected and secure environment to a wild and unpredictable natural world. Job is blocked from returning to his previous life. He corresponds to Adam and Eve after leaving the Garden of Eden, who are barred from re-entry and direct access to the tree of life (God)11 by cherubim and a flaming sword (see Genesis 3:24; Alma 42:2-3). Thus, cherubim and the flaming sword can also be conceived as a veil, an idea supported by the presence of embroidered cherubim in the veil of ancient Israel’s temple (see Exodus 26:31, 2 Chronicles 3:14). The tearing down of the hedge will move Job into realms of experience beyond guaranteed structure, something that will open up possibilities for new levels of understanding and becoming while entailing significant risk.

We now turn to Job outside the hedge in his lonely, dark, and bitter state.

Dialogues (Job 3–27)

First Cycle (Job 3–14). After seven days of silence on the ash heap with the three friends, Job’s anguish boils over. Surprisingly for the hero of a canonical text, Job curses the day of his birth, in effect saying that it would have been better never to have been born (see Job 3:1–10). Coming close to losing his integrity, Job has lost unquestioning trust in God. He raises a series of questions, asking why he did not die at birth and why God would give life and light to one who then suffers so bitterly as to desire death (see Job 3:11–26). Job refers longingly to Sheol (the realm of the dead) as a place where he would rest from suffering. It is uncertain at this point whether Job will search for death or for meaning, but Job’s wrestling with questions suggest that he has absorbed existential energy that may give him power to move forward.

Eliphaz, the first of the friends to speak (see Job 4–5), remonstrates gently with Job, reminding him that Job himself had previously counseled and strengthened those in similar circumstances (see Job 4:1-6). Job [Page 145]should not be impatient now that trouble has come to him. It is critical to remember that Job and his friends (community) begin with a common religious language and understanding. In his journey toward a transformed understanding of and relationship with God, Job will step out of and become differentiated from his community. The friends will continue to represent conventional religion and the wisdom of tradition, relying on their own experience (see Job 5:27) and the words of the elders (see Job 15:9–12), as Job once had.

In his first speech, Eliphaz anticipates all subsequent arguments the friends will make to Job. First he asserts that certain retribution holds: “Think now, who that was innocent ever perished? Or where were the upright cut off? As I have seen, those who plow iniquity and sow trouble reap the same” (Job 4:7–8, rsv).

In his second point, Eliphaz claims to have received a revelation, described in troubling terms: “dread came upon me, and trembling … a spirit glided past my face [and] the hair of my flesh stood up but I could not discern its appearance” (Job 4:14–16, rsv). The content of the revelation is even more troubling: that man cannot be righteous or pure before God and that man dies without wisdom (Job 4:17–21). This is precisely Satan’s position in the Prologue regarding Job — that Job would be unable to remain blameless and upright without the hedge. In contrast, God is seeking a man who will hold on to his integrity. By absorbing and expounding this spurious revelation, Eliphaz and the other friends unwittingly become representatives of Satan.

Eliphaz’s third and final point is that God will chasten man in hopes of bringing repentance before final destruction: “Behold, happy is the man whom God reproves; therefore despise not the chastening of the Almighty. For he wounds, but he binds up; he smites, but his hands heal” (Job 5:17–18, rsv). This text is a partial quote/partial paraphrase of Proverbs 3:11–12. Thus the friends — ministers of conventional religion — use the wisdom and understanding of men mixed with scripture, while unknowingly mediating Satan’s desires to Job.

Eliphaz is forced to assume that Job is a sinner because of his concept of retribution and the justice of God. He urges Job to understand the frailty and ignorance of man, admit his own sin, and lay his case before God, hoping for mercy and restoration (see Job 5:7–27). This is sage advice for any sinner. However, the reader knows from the Prologue that it does not apply to Job, and that for Job to follow Eliphaz’s advice would breach his integrity. Job’s challenge will be to “test and reject all the answers attempted by men.”12

[Page 146]Job responds (see Job 6–7) by complaining bitterly about his suffering, described metaphorically as being struck by poisoned arrows from God, and he excuses the rash words because he assumes an impending death (see Job 7:5–11). Indeed, Job loathes his life (see Job 7:13–16), which he describes as slavery imposed by God (see Job 7:1–6), and actually prays that God will kill him (see Job 6:8–9). At this point, Job has no hope of resurrection: “He who goes down to Sheol does not come up” (Job 7:9, rsv). Job laments that he has no strength, resources, or reasonable hope to continue on. Yet, the existential questions inside drive him on.

Job angrily inverts Psalm 8, which portrays man as God’s vice-regent on earth, asking: “What is man that thou dost make so much of him, and that thou dost set thy mind upon him?” (Job 7:17, rsv).13 This idea, which expresses gratitude to God in the psalm, now expresses horror at God’s treatment of man (Job). Job next ponders the question of why the sin of a mere mortal should make a difference to God (see Job 7:20–21). This question is critical and will recur several times in the book of Job.

Job then reproves his friends for being treacherous, presumably for failing to support his innocence in the face of his calamities (see Job 6:14-21). He pleads with them to show him his error and promises not to lie to them, clearly hoping that the friends will take his side and vindicate him (see Job 6:24–30). From this point on, Job’s suffering will stem more from rejection by friends/community than from the initial calamities detailed in the Prologue.

Bildad answers by calling Job’s words “wind” and then announcing a strict doctrine of retribution, even stating that Job’s children were killed because they sinned (see Job 8:4, niv), which the reader knows to be false.14 Bildad bases his assumption on the traditions of men handed down over generations (see Job 8:8–10). He even seems to mock Job, stating: “If you are pure and upright, surely [God] will rouse himself for you” (Job 8:6). Ironically, this does eventually happen, but not by Bildad’s prescription (see Job 42:7).

Chapters 9 and 10 put Job’s dilemma in sharp perspective. Like the friends, Job had always believed that the world was an orderly place, created and controlled by a perfectly just God who rewarded the righteous with good and the wicked with calamity. Now, as a result of his own experience, Job knows that this assumption is flawed. Disoriented, but firmly holding to the truth of his own innocence (see Job 9:15, 20, 21; 10:1), Job considers the possibility that God is simply an all-powerful bully who capriciously does whatever He pleases and calls it “right.” Having been marked by such a God for calamity, Job can never be clean [Page 147]or innocent in God’s grand scheme: “If I wash myself with snow … yet thou wilt plunge me into a pit” (Job 9:30–31, rsv); “though I am innocent, my own mouth would condemn me; though I am blameless, he would prove me perverse” (Job 9:20, rsv). Job laments the utter impossibility of contending against or even communicating meaningfully with such a being, who cannot be answered like a man (see Job 9:3, 11–12, 32–33).

From Job’s current perspective, God seems to “mock at the calamity of the innocent” and give the earth “into the hand of the wicked” (Job 9:23–24, rsv). Job wonders why God allowed him to be born or bothered to create him in the first place, simply then to torture him and cut his life short (see Job 10:5-9, 18–22). Ironically protesting that no one can ask God what He is doing, Job does precisely this, propelled forward by the need to understand why God is contending against him (see Job 9:12, 10; 2).

Another important theme appears in Chapter 10. After speaking of his public disgrace (see Job 10:15), Job charges God: “Thou dost renew thy witnesses against me … thou dost bring fresh hosts against me” (Job 10:17). Thus, the friends — witnesses against Job — seem to be exponents of a larger crowd phenomenon, which Job sees as coming from God. Job is still holding to his initial, untransformed understanding of God, which is shared with the community. The reader, though, already has reason to suspect that neither the friends nor their cosmic paradigm properly represent God.

Zophar now interjects to accuse Job of babbling untruth and mocking God, desiring that God would speak and properly rebuke Job (see Job 11:16). He even states that Job’s suffering is less than he deserves (see Job 11:6)! Zophar taunts Job with being unable to find out the deep things of God (see Job 11:7); Job is ironically already on a journey to do just that. Because he holds rigidly to a false paradigm of God, Zophar will be unable to join Job on the journey. Assuming that Job’s problem is sin, Zophar recommends repentance, promising restoration and temporal security: “You will lie down and, none will make you afraid” (Job 11:13-19, rsv). Zophar thus persists in doing the work of Satan by urging Job to admit guilt (breach his integrity by holding to a lie) in exchange for a (false?) promise of security.

Chapters 12–14 conclude the first cycle of the Dialogues. In my view, these critically important chapters constitute a turning point for the entire book. Here, Job reaches the greatest depths but then turns and begins his ascent toward a transformed relationship with God and a new level of understanding.

[Page 148]Job first sarcastically dismisses the friends’ wisdom, insisting that he also has understanding while ever mindful that, though innocent, he has become a laughingstock (see Job 12:1–4). Everywhere Job looks he sees injustice. He suffers while “the tents of robbers are at peace, and those who provoke God are secure” (Job 12:6, rsv). Job notes that God has all power (see Job 12:10, 12, 13), manifested both by control over nature (see Job 12:15) and human history (see Job 12:17–25). Accordingly, he places the blame for the injustice squarely on God, asking rhetorically: “Who … does not know that the hand of the Lord has done this?” (Job 12:9, rsv). Job even accuses God of bringing deep darkness to light (see Job 12:22, rsv). At this point Job is on the verge of breaking covenant, of rejecting God and going his own way in the world. Job has reached his darkest moment and deepest point of descent.

Astonishingly, Job now does an about-face, dismissing the friends as worthless physicians who speak falsely for God (see Job 13:4, 5) and conceiving a compelling desire to speak to God face to face (see Job 13:3, 10, 22–24). Job’s desire to see God, present his case, and repair his relationship is brought to powerful expression: “He may slay me, I’ll not quaver. I will defend my conduct to his face. This might even be my salvation, for no impious man would face him” (Job 13:15-16, translation by Pope).15

Job’s persistent, though not perfectly straight course to this goal will occupy the rest of the book. Job’s transformation has begun. He returns to some confidence in God’s justice, stating that God “will surely rebuke” the friends for their lies (Job 13:10) and inviting God to make him understand his current sins, if any, while admitting to iniquities in his youth (see Job 13:23-26).16

We now find Job oscillating between hope and despair. After noting that a tree, though cut down, may bud and put forth branches at the scent of water, Job laments that a man dies and rises not again (see Job 14:7-12). But then Job, in a flash of inspiration, suddenly receives his first great revelatory insight:

If only you would hide me in the grave and conceal me till your anger has passed!

If only you would set me a time and then remember me!

If a man dies, will he live again? All the days of my hard service I will wait for my renewal to come.

You will call and I will answer you. You will long for the creature your hands have made.

Surely then you will count my steps but not keep track of my sin.

[Page 149]My offenses will be sealed up in a bag; you will cover over my sin. (Job 14:13–17, niv)

Job thus conceives of a loving God calling him back to a meaningful relationship, with redemption from sin as necessary, and of the possibility of renewal of life in a resurrection. Although this vision is not immediately sustained, it represents a dramatic shift in Job’s understanding.

As Janzen notes, this “brief but incandescent vision of a positive outcome to his sufferings arises in the very context of his darkest suspicions.”17 However, it occurs only after Job has firmly committed to seeking God’s face. Janzen further suggests that this vision occurs “in response to a hidden call and hidden divine presence.”18 God, who has been reaching out to Job since the Prologue, now has a real, though tenuous, grip on Job. This ever-strengthening grip will aid Job in his journey out of bitterness and darkness and into the presence of God.

Second Cycle (Job 15–21). This cycle features prolonged pronouncements of the fate of the wicked, combined for the first time with direct assertions of sin against Job. Job also receives two additional revelatory insights.

Eliphaz charges Job with being filled with the east wind (a figure of destruction in the prophets — see Hosea 12:1, 13–15), dangerously doing away with fear of God, and having iniquity as the source of his words/inspiration (see Job 15:1–6). He tauntingly reminds Job that he has not participated in divine councils and reprimands him for rejecting the wisdom of the aged in favor of his own prideful assertions (see Job 15:7–10). Clearly sensing that Job is dangerous to the confessional unity of the community, Eliphaz returns to his supposed “revelation” of Job 4:12–21, reminding Job that man cannot be clean before God (see Job 15:11–16) and thereby reiterating Satan’s original contention (see Job 1:9–11). Eliphaz then launches into a prolonged (windy) affirmation of certain retribution against the wicked (see Job 15:17–35), stating: “The wicked man writhes in pain all his days” (Job 15:20). Eliphaz now clearly sees Job as one of the wicked.

Job responds (see Job 16–17) by dismissing his accusing friends as miserable comforters (see Job 16:1–5), realizing that the breach between them is irrevocable: “Come on again, all of you, and I shall not find a wise man among you” (Job 17:10, rsv). Job had previously hoped that his friends would serve as his advocates, attempting to vindicate him. Now, surrounded by hostile mockers and fearing a violent death (see Job 16:10–15, 17:2), Job realizes that there is no advocate for him [Page 150]anywhere on earth, and he appeals to the earth itself to serve as a witness by not covering his blood nor blotting out his cry (see Job 16:18).

In this awful state, Job receives his second great revelatory insight:

Even now my witness is in heaven; my advocate is on high. My intercessor is my friend as my eyes pour out tears to God; on behalf of a man he pleads with God as a man pleads for his friend. (Job 16:19–21, niv)

In the midst of unrelenting persecution on earth, Job, in a moment of inspiration, reaches out to a perceived advocate in heaven and prays that God Himself will provide the necessary pledge or witness on his behalf (see Job 17:2–3). This second revealed insight has a powerful effect on Job. Whereas he had previously yearned for death (see Job 3:1, 11; 6:8–9; 7:16), Job now refuses to yield to the grave or worm by letting go of his hope (see Job 17:11–16). Job has a new kind of hope, born of travail, that transcends anything he could have possessed before his “fall” (compare with Moses 5:11; D&C 29:39).

With the complete loss of community solidarity, Job’s hedge is now finally gone. He is speaking and acting freely with no hope of secondary gain in this world, with even speech itself giving no benefit (see Job 16:6). Job has not yielded to the lie nor cursed God. Satan appears to be losing. Will Job continue on his path to freely worshipping God?

Despite his revelatory insights and evolving understanding of God, Job often continues to use the language and paradigms he formerly shared with the friends, speaking of God as the source of his problems (see Job 16:7–14, 17:6). Yet, in the very same context he attributes his suffering to the mocking crowd of men: “Men have gaped at me with their mouth, they have struck me insolently upon the cheek, they mass themselves together against me” (Job 16:10, rsv). I suggest that Job’s inconsistency in first referring to God as his adversary (see Job 16:9, rsv) and then appealing to God to lay down a pledge for him (serve as his advocate) results from Job’s position between the old understanding once shared with the friends and a new understanding (paradigm) that will not culminate until Job speaks with God at the veil.

Bildad (see Job 18), resentfully perceiving that Job considers the friends as stupid cattle,19 insists that what Job is suggesting is tantamount to moving the entire earth for one man (see Job 18:1–4). Instead, the fixed moral order in the universe expels the wicked and remains stable (see Job 18:5–21). The wicked are caught in traps, are afflicted with consumption of the skin (Job!), are brought to the king of terrors, and leave no memory or descendants behind. Andersen notes [Page 151]that these are “the things most dreaded by an Israelite in life and in death as the tokens of rejection by God.”20 Bildad’s contention that the wicked leave no trace in the world rebuts Job’s hope that the earth will not cover his blood (see Job 18:17, cf. 16:18). In Bildad’s view, Job will have no witness in heaven nor on earth.

The argument continues with Job insisting that the friends are trying to “break [him] in pieces with words” (Job 19:2, rsv), consistent with Job’s practice in the Dialogues of complaining more about the friends’ verbal attacks than the calamities of the Prologue. Indeed, Job now sees the friends and the entire community, including his own wife and family, as “God’s troops” persecuting him on every side (see Job 19:5–22). Job is fast becoming a scapegoat for the crowd in a war of all against one. Job’s cry against the violence threatening him goes unanswered, prompting Job to pray that his words might indelibly be written in stone as a permanent witness. Paradoxically, as is clear from Job 19:5–22, Job still accepts the will and voice of the crowd in some sense as the voice of God, despite the contradiction between this idea and his ongoing revelatory insights.

In this turmoil, Job receives his third great revelatory insight:

For I know that my Redeemer lives, and at last he will stand upon the earth; and after my skin has been thus destroyed, then from my flesh I shall see God, whom I shall see on my side, and my eyes shall behold, and not another. My heart faints within me! (Job 19:25-27, rsv)

This third insight is more emphatic than the first two, consistent with Job’s ever firmer grip on an understanding of God. The idea of physical resurrection and seeing God are clear in the rsv translation above. Less clear is the idea, also contained in the Hebrew, that the Redeemer/Advocate will be God Himself. This concept is expressed in the New English Bible: “I shall discern my witness standing at my side and see my defending counsel, even God himself” (Job 19:26-27).21

Zophar, like Bildad, insulted by Job’s words and attitude, now makes a lengthy statement about certain retribution against the wicked (see Job 20). He also attacks Job’s confidence in an advocate in heaven, saying that “the heavens will reveal [the wicked one’s] iniquity and the earth will rise up against him” (see Job 20:27, rsv). Implicit in this thought is the assumed correspondence between the voice of the crowd or community on earth and God’s voice in heaven. While Zophar’s words (see Job 20:12-22) have value in understanding the nature of sin and its consequences, they do not apply to Job. The friends never consider the [Page 152]suffering of the righteous because they are blinded by a rigid theology in which it never occurs. Zophar’s concluding point — “This is the wicked man’s portion from God, the heritage decreed for him by God” (Job 20:29 rsv) — will later be quoted by Job as he apparently composes a speech for Zophar (see Job 27:13).

Job concludes the second cycle by imploring his friends to see, as he has, that retribution does not hold in this world (see Job 21). He refutes Zophar’s last argument almost point by point, finally appealing to the testimony of travelers, who have observed much of the world, that the wicked rarely experience calamity (see Job 21:29–30). Job takes particular exception to the friends’ idea that “God stores up [the iniquity of the wicked] for their sons” (Job 21:19, rsv; see also Job 20:10, 18:15–19), suggesting, instead, that God should properly recompense each person for his or her own deeds. However, the friends’ concept of God punishing the children for the sins of their fathers does find support in scripture (see Exodus 20:5); thus, we have another instance of the friends mixing scripture with accumulated human tradition (see also Job 15:9–10).

Job observes, concerning the wicked, that they say to God: “Depart from us” (Job 21:14), leaving the obvious point unstated that they should be demanding that Satan depart instead of God. Job is familiar with this temptation, having once wished that God would “let him alone” (Job 10:20). Now, Job maintains that the “counsel of the wicked is far from [him]” (Job 21:16, rsv), while accusing the friends of concocting schemes to wrong him. Job condemns the comfort of the friends as empty and their answers as falsehood (see Job 21:34).

Third Cycle (Job 22-27). Given the increasing level of acrimony and disagreement, it is no surprise the dialogue aborts in the third cycle in a failure of communication, a failure of language itself.

Eliphaz makes a last valiant effort to make Job see things his way (see Job 22). He argues that man and his knowledge are nothing before God; therefore, man has no right to question or judge God (see Job 22:2, 11–14). Eliphaz is correct to some extent; however, the problem is that Job is actually challenging the friends’ false premise about God that all suffering is merited because God is just. Unable to see this, Eliphaz both misjudges Job’s righteousness and fails to perceive Job’s journey to a deepened understanding of God. Eliphaz holds tenaciously to the idea that he understands God correctly — and thus speaks for God — despite the contradictory evidence around him, most obviously in the life of Job.

[Page 153]Eliphaz’s distorted conception of God is clear in the rhetorical question he presents Job: “Is it any pleasure to the Almighty if you are righteous, or is it gain to him if you make your ways blameless?” (Job 22:3, rsv). Eliphaz clearly assumes the answer is “no.” Here, Eliphaz speaks falsely, saying God is indifferent to (without passion for) human virtue. In fact, the entire drama of Job was precipitated precisely because God does prize human uprightness and blamelessness (see Job 1:8).

Because of Job’s suffering, Eliphaz can see Job only as guilty, as keeping to the “old way which wicked men have trod” (Job 22:15, rsv) and languishing in darkness, insensitive to the truth (see Job 22:11). Now, for the first time, he accuses Job of great wickedness and endless iniquity (see Job 22:5). He specifically charges Job with oppressing the poor and powerless, even stripping their limited possessions for gain. Job will vigorously deny these charges under oath in chapter 31. The very unreasonableness of these accusations supports the idea that Job is being made a scapegoat for the sins of the community at large.

Eliphaz admonishes Job to “agree with God and be at peace” (Job 22:21). However, for Eliphaz this means to agree with him and the community he represents. Clearly in rivalry with Job, Eliphaz also claims that “the counsel of the wicked is far from [him]” (Job 22:18, rsv; see also Job 21:16). Eliphaz asks Job to return to God, laying his own gold (insistence on his own righteousness and understanding — his integrity) in the dust in order to make God his “gold” (see Job 23:23–25). Continuing to speak for God, Eliphaz promises Job restoration, even to the point (in niv and Pope translations22) of his making intercession for the guilty and facilitating their deliverance (see Job 22:27–30). Eliphaz now, however, clearly sees himself in this role with respect to Job. Ironically, it will be Job in the Epilogue, after coming to confessional agreement/unity with God at the veil, who will make intercession for the friends (see Job 42:7–9).

Ignoring Eliphaz, Job expresses a fervent wish to find God and present his case in person, reaffirming his previous resolution to seek God no matter the consequences (see Job 23:3–5, cf. 13:13–24). Job’s overwhelming desire is a face-to-face meeting with God, not by contrived repentance as recommended by Eliphaz (see Job 22:21–30), but in honesty and fairness.23

Pondering meeting God, Job receives his fourth great revelatory insight:

Would he contend with me in the greatness of his power? No; he would give heed to me. There an upright man could reason [Page 154]with him, and I should be acquitted forever by my judge. Behold, I go forward, but he is not there; and backward, but I cannot perceive him; on the left hand I seek him, but I cannot behold him; I turn to the right hand, but I cannot see him. But he knows the way that I take; when he has tried me, I shall come forth as gold. (Job 23:6–10, rsv)

Significant changes have occurred in Job. He now realizes that he can speak to God with reason and honesty (contrast with Job 9:32). He understands that God will not simply overwhelm him with His greater power and that acquittal can be expected (contrast with Job 9:20, 30–31). Not yet having seen God and despite having awareness of much injustice in the world, Job is now able to trust God’s purposes and concern for him. Finally, Job comprehends that his trials have a transforming purpose, which will bring him forth as “gold,” as something of great value to God. Job’s “golden” soul will be the answer to God’s (and Job’s) existential questions.

Job affirms that he has treasured the word of God, kept His commandments, and stayed in God’s way or path, reminiscent of the faithful in Lehi’s dream (see Job 23:11-12; see also 1 Nephi 8:30; 2 Nephi 31:17-0). Nonetheless, despite confidence in God’s purposes, Job is afraid of the prospect of further suffering (see Job 23:13–16). Job laments: “I am hemmed in by darkness, and thick darkness covers my face” (Job 23:17). Having received his fourth great revelatory insight and nearing the end of his journey, Job is more than ever cognizant of the veil of darkness separating him from God.

Job now considers not just his own suffering but that of others, particularly the poor and powerless (see Job 24:1–12), his suffering having deepened his empathy for others. While Job had always cared for the poor and oppressed (see Job 31:13–23), he now feels their suffering in a new and profound way. Like Habakkuk (see Habakkuk 1:12–13), Job is impatient for God to bring justice to all and put things right. Job reiterates once again the truth that the wicked often thrive at the expense of others, despite the assertions of the friends to the contrary (see Job 24:13–25).

Bildad interjects with praise of God’s greatness and man’s inability to be just or righteous before God, agreeing with Eliphaz (see Job 25:1–3; see also Job 4:17–19, 15:14–16). Bildad answers the question of Psalm 8 (What is man?) by saying that man is a maggot or worm (see Job 25:6)! Thus, Bildad distorts Psalm 8 to strip humans of any royal potential before God.24 Having none of this, Job sarcastically criticizes [Page 155]both Bildad’s ability to counsel and the source of his inspiration (see Job 26:1–4). Job then seems to “finish” Bildad’s speech for him by creating a parody of his position on the greatness of God (see Job 26:5–14).25 Meaningful dialogue has aborted.

That Job has maintained his integrity is made clear in his next response (see Job 27:1–6). Job takes an oath in the name of God that he will not lie and that he will continue to hold fast to his integrity and righteousness, in effect binding himself to God in covenant fidelity. He will not falsely admit (major) sin in order to avail himself of grace, as the friends have proposed, nor will he respond with evil despite his unjust suffering. Although nothing seems to justify it, Job remains loyal to God, freely worshipping him. God now seems to have the man He has been reaching out for since the Prologue. Job closes chapter 27 (see Job 27:13-23) with an apparent caricature of the friends’ (especially Zophar’s) description of the fate of the wicked, even quoting Zophar (Job speaking in Job 27:13, Zophar speaking in Job 20:29).

As mentioned, speech and language are critical in the Joban drama, where truth is presented by means of dialogue. Job and the friends had shared a common language and confessional unanimity and, thereby, a common life, a common being. The Dialogues have been a war of words where Job attacks the friends’ words (see Job 9:2, 12:2, 16:25, 19:2–3, 21:34, 26:1–4) and vice versa (see Job 8:2, 11:2–3, 15:2-3, 20:2–3). Job asks, “How long will you torment me, and break me in pieces with words?” (Job 19:2 rsv), illustrating the importance of speech and its relationship to being. Similarly, Job’s words, which threaten the established social order, “greatly disturb” and trouble Zophar (see Job 20:2, niv). In Job, speech and language are emblematic of and partly constitutive of being. Responding to God’s call, Job no longer meaningfully participates in the language and being of the friends. Dialogue between them is no longer possible. Job is grasping forward toward a new level of being and understanding suggested by the four great revelatory insights, which betoken a transformed understanding of God and man.

Job Prepares to Meet God (Job 28–37)

At this point in Job, we reach a new level or stage in the drama. Having tasted the wisdom of man (mixed with scripture) and found it wanting, Job has moved beyond dialogue with the friends and waits, instead, on God. In chapter 28, Job will meditate on the nature of wisdom, concluding that it ultimately must come from God. Job will review his past and present life in chapters 29 and 30. In chapter 31, Job will [Page 156]affirm his innocence and recommit himself in covenant fidelity, using self-imprecatory oaths and crying out that God will hear his words. In chapters 32–37, Job will face his last and possibly greatest test by Elihu. Elihu will try, without success, to engage Job in dialogue in order to bring him back to unity with the friends and derail his quest for God’s face.

Job 28-31 (Job Steadfast in Covenant Fidelity). Although the text does not make it explicit, I consider chapter 28 to be Job’s hymn to wisdom. Job praises human ingenuity, demonstrated by mining technology (see Job 28:1–14), but states of true wisdom that “man does not know the way to it” (Job 28:13, rsv). Yet, on another level, human mining is analogous to Job’s recent experience, occurring in loneliness away from people, taking place in darkness on hidden paths, bringing hidden things to light, and producing gold and sapphires that have been transformed by fire. These descriptions of mining apply equally well to Job’s spiritual journey. Job then moves on to consider human commerce in precious stones and metals, noting that none of these can purchase wisdom (see Job 28:15–22). Yet, the Dialogues can be understood as an analogue to human commerce. The question is whether Job’s experiences have produced true wisdom. Job’s previous statement about coming forth as gold, after being tried by God (see Job 23:10–11), suggests that he has indeed gained wisdom.

Job concludes his hymn to wisdom by noting that God knows the way to it and that God established wisdom at creation, saying: “The fear of the Lord — that is wisdom” (see Job 28:23–28, rsv). On the surface, Job seems to say that God alone knows where wisdom is and the best that man can do, since he cannot find wisdom, is to fear God. However, this seems a bit banal and echoes the words of Zophar (see Job 11:7–9), who will be judged as speaking falsely of God (see Job 42:7–9). I propose an alternative reading. God alone understands the way to wisdom — for man. The way is to create earth for man, whereupon God can then share His existential questions and, thereby, potentially His wisdom and being. Man, by responding well to these existential questions participates with God in the creative process and learns wisdom.

True wisdom is found by free entry into risky acts of creation while maintaining fidelity to God. To come forth as gold, men must participate with God in the creative process of bringing forth that gold. Seen this way, the key existential question is whether man will participate with God in creation or go his own way. Job has sought God with fidelity, and his response has been creative, departing entirely from the conventional religious thinking of the crowd. Job is coming forth as gold; he and God [Page 157]will have a new common ground on which to meet, a shared higher level of being.

Job, now cut off from dialogue with the community, reflects on his life. Chapter 29 gives the fullest description of Job’s life before his “fall.” He then perceived God’s companionship and friendship (see Job 29:2–5), even stating that “the rock poured out for me streams of oil” (see Job 29:6, rsv), reminiscent of Adam’s easy access to food in the Garden of Eden. Beyond this, Job served as champion for the poor, sick, and powerless, with men waiting for Job’s counsel “as for the rain” (Job 29:23). Job’s voice was almost like the voice of God: “I chose their way, and sat as chief, and I dwelt like a king among his troops” (Job 29:25, rsv). Thus Job served as a royal, mimetic model, expecting a fulfilling life as a friend of God and man.

Now, all of this has been inverted (see Job 30). Even the lowest stratum of society, which Job now admits to having once disdained, mocks and spits at Job (see Job 30:1–10). Having been ostensibly marked as a sinner by his calamitous suffering, Job is now clearly a scapegoat for the crowd. The difference between royal model and despised scapegoat is all in the eyes of the multitude. As before, Job attributes his troubles at one moment to God (see Job 30:11, 19–23) and, at the next, to the crowd (see Job 30:9–10, 12–15). While Job has already rejected the friends’ explanation of his suffering and the voice of the crowd (the friends) as the voice of God, perhaps he does not yet fully discern the difference between favor in the eyes of God and favor in the eyes of men. He still sees his previous material prosperity and high societal rank as evidence of the presence of God in his life (see Job 29:1–6).

Although Job assumes an impending death at “God’s hand,” Job continues to cry out to God for help (see Job 30:20), supplementing this by cries for help in the assembly (see Job 30:28). Job perceives himself as being “reduced to dust and ashes” (see Job 30:19, niv). This highly significant phrase will be critical in understanding Job’s response to God at the veil.26 In the only use of this phrase outside Job, Abraham used “dust and ashes” to refer to mortal man in general (see Genesis 18:25–27). Man arises from dust and, in death, is reduced to ashes.

Job next takes an oath of innocence (see Job 31) before God (see Job 31:2, 6, 14, 23), affirming that he has not been guilty of fourteen sins27 or seven categories of sin,28 with the number seven signifying completeness.29 Job has been faithful in all things. The oath has the effect of binding or consecrating Job in solidarity to God and his fellow man. This solidarity is perhaps brought to fullest expression in the following statement: “If I [Page 158]have rejected the cause of my manservant or my maidservant … what then shall I do when God rises up? When he makes inquiry, what shall I answer him? Did not he who made me in the womb make him? (Job 31:13–15, rsv). Job is thus committed to treating his neighbor as himself before God.

On five occasions, Job invokes self-imprecations — curses against himself — if he has not been or will not be true to his oath of innocence.30 The most explicit of these is Job’s statement: “If I have raised my hand against the fatherless … then let my shoulder blade fall from my shoulder, and let my arm be broken from its socket” (Job 31:21–22, rsv). These self-maledictions are a further expression of Job’s self-sacrifice or self-consecration in absolute fidelity to God and his fellow man.

Job’s self-consciousness of his innocence and commitment to righteousness give him confidence to approach God (see Job 31:23; see also Hebrews 10:19–23; 1 John 3:16–20, 4:16–19, 5:14; D&C 121:45–46). For a final time, Job cries out that God will hear his words, being willing to wear any indictment against himself as a crown and to approach God like a prince (see Job 31:35–37). In the last self-imprecation, Job invokes a curse of the Fall that “thorns grow instead of wheat” (Job 31:40, rsv; see also Genesis 3:17–18). Job only invokes these curses because he is confident he will not have to suffer them. This suggests that Job is ready to have the Fall reversed, much like the brother of Jared: “And when [the brother of Jared] had said these words, behold, the Lord showed himself unto him and said: Because thou knowest these things ye are redeemed from the fall; therefore ye are brought back into my presence” (Ether 3:13).

A narrative voice now informs the reader: “The words of Job are ended” (Job 31:40, rsv). Job has passed through the calamities of the Prologue and the dark bitterness of the Dialogues, holding on to his integrity partly by virtue of four great revelatory insights. He is prepared to meet God — except for one final test.

Job 34-37 (Job Tried by Elihu). No part of the book of Job has aroused more controversy than the speeches of Elihu, with some praising their literary style and intrinsic value and others denigrating them as banal.31 I will look in detail at what Elihu says and does before reaching conclusions.

Elihu, found nowhere else in Job, suddenly appears, introduced in prose and given a human pedigree (see Job 32:1–5). The name Elihu means “He is my God.”32 The question is whether he refers to the Lord or to Elihu himself, raising the possibility of an idolatrous connotation. [Page 159]Elihu’s anger at Job for maintaining that he is righteous and at the friends for not winning the argument is here mentioned four times. Why should Elihu be so angry?

Ironically, Elihu offers no truly new ideas. Elihu affects a sense of modesty, claiming he waited for those older and presumably wiser than him to speak first (see Job 32:6–7), but then denigrating the friends’ “wisdom” and refusing to use their speeches (see Job 32:11–17). He seems to be full of pride as well as anger. Elihu also claims to be a revelator — full of the Spirit, the breath of the Almighty, which constrains him to speak (see Job 32:8–10, 18–20; 33–34). Finally, Elihu guarantees that he will speak honestly without flattery; otherwise, he says, God would soon remove him (see Job 32:21–22, 33:3).33 This last statement rings false because God permits hypocrites and flatterers significant latitude in mortality (see D&C 50:2–8; Mosiah 27:8). One cannot trust another’s honesty simply because God has not yet “removed” him.

Unlike the friends, Elihu frequently calls Job by name, both to Job himself (see Job 33:1, 31; 37:14) and to the crowd (see Job 34:5–7, 35, 36; 35:16), and repeatedly tries to draw Job into conversation (see Job 33:5, 32; 34:33; 35:2), as God will subsequently do (see Job 38:3, 40:7). Job continually resists interchange with Elihu. Elihu, more confrontational than the friends, accuses Job of contending with God and categorically dismisses Job’s claims of innocence and purity (see Job 33:9–13). He mentions to Job the possibility of an angel mediator (presumably Elihu himself!) who will intercede for him if only Job will admit guilt, even claiming that he desires to justify or vindicate Job (see Job 33:19–32). This “justification” is precisely the opposite of the kind Job is seeking, but it illustrates that Elihu will do or say anything to entice Job to let go of his integrity.

Elihu’s perspective on divine revelation is instructive: “In a dream … while they slumber … he opens the ears of men and terrifies them with warnings” (see Job 33:15–18). This terrified response to “revelation” is reminiscent of Eliphaz’s dread and trembling during his night vision, a vision that communicated Satan’s position from the Prologue that a man (Job) could not be truly just before God (see Job 4:12–18, 1:8–11). Elihu also reiterates Eliphaz’s idea that God uses suffering to chasten men and bring them to repentance (see Job 33:19–27, 5:17–18). This idea is true in a sense (as Elihu mixes truth with lies), but it does not apply to Job.

Elihu directs his second speech (see Job 34) to the crowd, publicly denouncing Job for sin at both the beginning and end of his speech (see Job 34:1–9, 31–37). He accuses Job of scoffing at God, walking with [Page 160]the wicked, speaking without knowledge, and adding rebellion to his original sin. He attacks Job for supposedly demanding that God “make requital” (Job 34:33, rsv) or dispense justice to suit Job. This is strange behavior for one who claims to desire Job’s justification.

In the center of this speech, Elihu portrays his vision of God (see Job 34:10–30). According to Elihu, God is in complete control of the earth, sustaining life by His breath, ruling with indisputable righteousness and justice, and bringing the wicked to their deserved and timely end without bothering to bring any man before Him in judgment (see Job 34:23–24). This “God” seems far removed from the One who sent Jesus Christ to be lifted up on the cross that men might be lifted up to God to be judged for their works (see 3 Nephi 27:14–15).34

Furthermore, Elihu’s picture of God dogging every man’s steps in order to bring punishment on him as soon as he sins (see Job 34:21–25) reeks a bit of compulsion. This suspicion is strengthened by considering Elihu’s rhetorical question: “Who gave him charge over the earth?” (Job 34:13, rsv). Elihu’s assumed “no one” suggests a God who unilaterally imposes His will on mankind. This idea is subverted by D&C 121:46, which speaks of everlasting (divine) dominion as proceeding without compulsory means, in contrast to Satan’s plan of compulsion (see Moses 4:1–4).

Elihu, amplifying a previous point of Eliphaz (see Job 22:2–3), now confronts Job with God’s supposed indifference to human wickedness or righteousness: “If your transgressions are multiplied, what do you do to him? If you are righteous, what do you give to him?” (Job 35:6–7). Elihu wants Job to believe that neither he nor his righteousness matter to God. The reader, of course, knows from the Prologue that this is false. God’s fervent desire is a “golden” Job. Elihu continues to berate Job, claiming that he “multiplies words without knowledge” (Job 35:16, rsv) in demanding to speak with God about his case, and assures Job that God will not respond to his empty cry nor come to him (see Job 35:9–16). These assertions will shortly be proved false.

Elihu begins his fourth speech (see Job 36–37) with an astounding claim: “I have yet something to say on God’s behalf. I will fetch my knowledge from afar … for truly my words are not false: one who is perfect in knowledge is with you” (Job 36:2–4, rsv; emphasis added). Shortly after, Elihu extols God as one “who is perfect in knowledge” (Job 37:16). Thus, he puts himself alongside and equal to God in a sense. The implication is that since Elihu shares common knowledge with God, his words are the words of God. Job must therefore decide whether to [Page 161]accept Elihu as a true prophet or continue to wait on the Lord. Hoping that Job will indeed give up his quest for God and accept him instead, Elihu reminds Job once more of his sin and urges him to repent (see Job 36:17–21).

Most of Elihu’s fourth speech consists of now-tiresome perorations about God’s majesty, the certainty of retribution against the wicked, the use of suffering as temporary divine discipline, God’s inscrutable and indisputable ways, and the presence of God’s voice and power in nature. However, in three places, Elihu’s mask slips completely:

- “Behold, God is great, and we know him not” (Job 36:26, rsv; emphasis added).

- “Teach us what we shall say to him; we cannot draw up our case because of darkness. Shall it be told him that I would speak? Did a man ever wish that he would be swallowed up?” (Job 37:19–20, rsv; emphasis added).

- “God is clothed with terrible majesty. The Almighty — we cannot find him; he is great in power and justice” (Job 37:22–23, rsv; emphasis added).

In other words, Elihu says that man cannot find, speak to, or know God. Unlike a true prophet who facilitates his listeners’ journeys toward God, Elihu is a false prophet, doing anything he can to stop Job from meeting God.

As the reader has likely surmised, I see Elihu as a figure for Satan, much like the serpent in the Garden of Eden. This idea was first proposed by David Noel Freedman:

I believe that Elihu — who comes from nowhere and disappears from the scene as soon as he is done with his speeches — is not a real person at all. Like the other participants, he has a name and a profession, but it is a disguise … He is the person assumed or adopted by Satan to press his case for the last time.35

In my view, Elihu’s otherworldly nature is also indicated by the prose introduction at his arrival. Seeing Elihu as Satan explains Elihu’s extreme anger (at losing the battle for Job’s soul to God), his pride, his absence from the Epilogue (on the other side of the veil where Job has overcome all evil), his pervasive lies, the potential idolatrous connotations of his name, his aggressive and repeated accusations of Job (Satan = adversary), and his prolonged attempts to turn Job from his course to God.

[Page 162]Understood in this light, Elihu’s speeches take on new significance, constituting Job’s final and greatest test. Rather than viewing Elihu as derivative and secondary to the friends, he should be viewed as the source of their well-intended but distorted advice. Elihu is the final barrier Job must pass before speaking with God at the veil. He thus occupies the place of Satan before Joseph Smith’s first vision (see JS–H 1:16–17) and before Moses’s greatest visions (see Moses 1:9–27). In the latter, Satan demands that Moses worship him and responds angrily when Moses refuses, frightening Moses and shaking the earth. Elihu’s angry purpose with Job is similarly to frighten him back to the disoriented state of chapters 3, 6, 7, 9, 10, and 12 before Job firmly resolved to seek an audience with God.

Job at the Veil (Job 38:1–42:6)

Like the Elihu speeches, this part of the book of Job has resulted in a great deal of controversy. A superficial reading sees God as a verbose, omnipotent bully (as Job had feared; see chapter 9) who paraphrases words of Elihu (compare Job 38:2 with Job 35:16) and frightens Job back into humble, unquestioning subservience. Job is seen as accepting the advice of the friends to repent and agree with God (see Job 11:13–18, 22:21–30) and as thus receiving restoration of health, wealth, and family. This reading is seemingly supported by translations of Job 42:6, which have Job repenting in “dust and ashes” and self-abasingly confessing ignorance and sin. I argue, following Janzen36 and Andersen,37 that such interpretations make nonsense of the entire book. The Lord’s words in the Epilogue — that the friends “have not spoken of me what is right, as my servant Job has” (Job 42:7–8) — require that we interpret the book differently.

God’s coming to Job at Job 38:1 brings to culmination what both God and Job have been seeking since God first reached out to know Job in the Prologue. The Lord speaks with Job, conferring dignity on him, and challenges him to stand up and answer. God does not demand that Job give up his claim of innocence nor explain the reason for Job’s suffering but gently defends Himself against Job’s accusations of malign intent (see Job 38:2, 40:8, see also Job 12:22). There is no hint given that it is not for man to question God. Indeed, God answers Job’s questions with counter-questions, inviting him to deeper understanding.

Janzen insightfully summarizes these issues as follows:

God finally answers Job. But the answer, unlike those of the friends, gives no reason for Job’s sufferings. It is as though [Page 163]those sufferings are simply left enshrouded in the mystery of their givenness, their having happened. All God does is to deny Job’s charges of dark purpose and indifference to justice and to ask Job three sorts of questions: Who are you, Where were you? Are you able? On the face of it these questions are rhetorical and have the specific force of impossible questions to which the proper answers are, I am nothing, I was not there, and I am not able. Yet again and again throughout the divine speeches, images and motifs and themes from earlier in the book are taken up and re-presented in such a way as to engender the suspicion that these apparently rhetorical questions are to be taken ironically, as veiling genuine existential questions posed to Job. The questions, as from another burning bush, have to do with the issue of Job’s willingness to enter upon human vocation to royal rule in the image of God, when the implications of that image are intimated in terms of innocent suffering.38

Thus, the “questions of creation” addressed to Job in chapters 38–41 should be seen as a creative divine call asking for a response from Job, much like the existential questions of the Prologue. Will Job participate in and take responsibility for creation, despite unavoidable innocent suffering and the presence of evil?

God’s First Speech (Job 38–39). God steps into the tumult of opinion, which is mirrored by a literal whirlwind, finally stating His fundamental question about Job to Job himself: “Who is this?” (Job 38:2). I suggest that Job is now essentially “gold,” still blameless and upright despite loss of his hedge. God chides Job for darkening His “counsel by words without knowledge” (Job 38:2; see also Job 12:13–22). Ironically, Job has been in the dark (see Job 23:17) but was gaining knowledge (see Job’s four great revelatory insights) as a result of absorbing God’s existential questions, and now God has come to endow him with more knowledge (see Job 42:3). God challenges Job to respond to His questions “like a man,” making God to know (see Job 38:3), thus fulfilling Job’s hope (see Job 23:7) against his earlier despair (see Job 9:32). Two chapters of uninterrupted questions related to the created order then follow.

God asks who shut in the sea and set bounds for it (see Job 38:8–11). “Sea” functions as a metaphor for primal chaos or evil — which, like Satan in the Prologue, are permitted in creation but are bounded in some way. God then alludes to a coming day when the wicked will [Page 164]be shaken out of the earth, cut off from light, and rendered powerless (see Job 38:12–15; see also Heb. 12:26). Like the sea and Satan, evil men are also permitted in the created world but are ultimately bounded (see D&C 76:98–108).

God queries Job if he has walked in the recesses of the deep, if he has seen the gates of death, and if he knows the way to the dwelling of light (see Job 38:16–21). Job has indeed walked through the deepest darkness, by the gates of death, and to the place where light dwells (in God Himself)! God asks Job to consider His creative use of water (see Job 38:22–30). God makes rain fall in the desert, even in the absence of man, to bring forth grass and satisfy the desolate land (see Job 38:26–27). Analogously, Job has been in the desert, cut off from meaningful contact with his fellow man but receiving revelatory insights from God in a creative process. God questions Job about having knowledge of the “ordinances of the heavens” and the ability to establish their rule on earth and whether he grasps the wisdom in the clouds (see Job 38:31–38). Ironically, God is, and has been, endowing Job with wisdom by His existential questions.

God implicitly affirms His responsibility for creation and its consequences (see Job 38:39–41), and asks Job to consider wild animals in the wilderness — whose natures are analogues of fallen natural man — which God permits in the world (see Job 38:39–39:30). Rule over wild, mysterious animals is analogous to divine rule over the world of fallen men, free to follow their own desires. Just as the ostrich stupidly permits her own eggs to be trampled, so does innocent suffering occur in the world (see Job 39:13–18). The poetic images of the wild ass/wild ox are particularly instructive with respect to Job (see Job 39:5–12; see also Job 6:5, 11:12). These animals roam the wasteland (like Job), having been set free (like Job without the hedge). The question is whether they will willingly return to a human master or, in Job’s case, whether Job will freely worship God without the benefit of the hedge.

Job’s First (Non) Response (Job 40:1–5). Characterizing Job as one who contends with deity, God asks him if he still wishes to correct His justice (see Job 40:1–2). God thus challenges Job to deeper understanding and loyalty, and God clearly desires an answer. Job, however, is not yet ready to respond to the Lord (see Job 40:3–5). He mentions a sense of unworthiness (niv) or insignificance (rsv) as justification for his reticence and retreats into silence. Job’s feelings of inadequacy before the Lord correspond to those of the brother of Jared in his question-and-answer session at the veil before entering into the Lord’s presence [Page 165](see Ether 3:2–14). M. Catherine Thomas’s commentary on this text applies also to Job: “As the unredeemed soul, even a guiltless one, closes the gap between himself and his Maker, he perceives the contrast as so overwhelmingly great that he is sorely tempted to shrink back, to give up the quest.”39

The image of Job “contending” with the Lord at the veil resonates with several others. The patriarch Jacob wrestled all night with a man (God) before seeing him face-to-face and receiving a blessing instead of the requested name of God (see Genesis 32:22–30). Enos wrestled all day before God, hoping to experience a remission of sins, before hearing the Lord’s voice and probably seeing His face (see Enos 1:2–8, 19). Habakkuk, like Job, struggled with the presence of violence and injustice in the world (see Habakkuk 1:2–4) before hearing God’s voice (see Habakkuk 2:1–4) and seeing God’s glory (see Habakkuk 3:3–6). Job’s experience at the veil is profitably compared with these.

God’s Second Speech (Job 40:6–41:34). God again challenges Job to answer Him (see Job 40:), asking if Job would condemn God in order to justify himself (see Job 40:8). In the rigid theology of retribution that Job once shared with the friends, they concluded he was sinful because he suffered. Job, initially locked into the same theology but knowing he was innocent, was forced to question God’s justice (see Job 9:15–33, 12:13–25). By the standards of this theology, either God or Job was unjust/unrighteous. As we have seen, that understanding of God and man collapsed for Job in the Dialogues, being replaced by fragments of new religious understanding (the four great revelatory insights) that will lead to transformation in Job, including the understanding that he does not have to condemn God to justify himself.

In order to elicit or amplify a transformed understanding of true justice (ruling in love without compulsion — see D&C 121:34–45), God ironically invites Job to use raw power and coercively solve all of the inequities in the world, punishing the proud and wicked while clothing himself in glory (see Job 40:9–14)! Job apparently demurs, probably realizing that compulsive force cannot bring good out of evil and that use of such power is corrupting. As a final tutorial, God gives Job the examples of Behemoth (see Job 40:19–24) and Leviathan (see Job 41:1-34). Behemoth is the Hebrew plural for “beast” and is probably a poetic description of a hippopotamus. Leviathan, the seven-headed sea dragon of Canaanite myth, is here likely a poetic description of a crocodile. Though part of God’s creation, these beasts are wild, ferocious, and unable to be tamed. As such, they typify the proud (see Job 41:34) [Page 166]and hard-hearted (see Job 41:24) who are unable to be led or made party to a covenant with God (see Job 40:24–41:4). Assuming responsibility for creation implies, in some sense, taking responsibility for such, yet creatively providing for redemption without using compulsory means.

Job’s Second Speech (Job 42:1–6) — Job Penetrates the Veil. Initially not prepared to speak to the Lord (see Job 40:3–5), Job now responds, bringing the book to its climax. The meaning of this text is somewhat unclear, particularly in verse 6, and I here provide two different translations:

1. Janzen translation40

2a. You know that you can do all things,

b. and that no purpose of yours can be thwarted.

3a. “Who is this that obscures design

b. by words without knowledge?”

c. Therefore, I have uttered what I have not understood,

d. things too wonderful for me which I did not know.

4a. “Hear, and I will speak;

b. I will question you, and you will make me to know.”

5a. I have heard you with my own ears,

b. and now my eye sees you!

6a. Therefore, I recant and change my mind

b. concerning dust and ashes.

2. rsv translation

- I know that thou canst do all things, and that no purpose of thine can be thwarted.

- “Who is this that hides counsel without knowledge?” Therefore I have uttered what I did not understand, things too wonderful for me, which I did not know.

- Hear and I will speak: “I will question you, and you declare to me.”

- I had heard of thee by the hearing of the ear, but now my eye sees thee:

- Therefore I despise myself, and repent in dust and ashes.”

Janzen follows the Hebrew consonantal text to get “you” instead of “I” (from the Masoretic vowels) at the beginning of verse 2, seeing this as a stronger affirmation of Job’s confidence in God’s power: “To say ‘you know’ is to confess one’s agreement with that which is grounded [Page 167]outside the self …. [It] is to bring one’s own views … and structures of understanding under the judgment of another knowing which far transcends one’s own.”41 Job is now able to confess ultimate confidence and trust in the Lord.

The quotation marks in verses 3 and 4 are critically important because they indicate where Job is quoting or closely paraphrasing actual words of God from God’s first and second speeches (42:3a = 38:2; 42:4b = 38:3b & 40:7b). Job thus repeats or takes up words of the Lord, making them his own and coming to confessional unity with the Lord.42 After forty-one chapters of nothing but disagreement, ending in complete failure of communication between Job and the friends, Job now makes God’s language his own. This is emblematic of entering into a higher-level covenant relationship with the Lord and participating more fully in His life and being. Job’s participation in the divine nature brings to fulfillment God’s covenant desire to share His life/being with man (see Moses 1:39; 2 Peter 1:3–4).

In verse 3, Job admits to having gained a transformed understanding of wonderful things not previously understood. What these things might be is not specified, and one would probably have to join Job, Jacob, Enos, Habakkuk, and the brother of Jared at the veil to achieve the same understanding. I suggest that Job’s transformation includes a spiritually deepened comprehension of several things: first, God’s power to rule in love without force; second, God’s infinite concern and love for “dust and ashes” (man); and third, man’s calling and capacity to share common ground with God — language and being.

Having spoken to the Lord through the veil, Job now acknowledges that he has come into God’s presence (see Job 42:5), bringing to fruition the quest for God’s face initiated soon after his calamities began (see Job 3:3, 13–22). Job stands in marked contrast to the friends. They never cry out to God nor seek His presence, trapped by complacent acceptance of a limited, conventional understanding of God. The friends confuse uncritical reception of traditional wisdom with reverence and the dispensing of platitudes about God with a true search for God’s face. Their fear of uncertainty and risk makes them incapable of joining Job and approaching God. Job’s much-praised “patience” consists of his incessant, though far from quiet or uncomplaining, push through darkness toward the face of God.