Abstract: Heavenly ascent describes the process of an individual (or community) returning to the presence of God. Though various elements exist within heavenly ascent literature, general patterns can be discerned. This project uses one such pattern as a hermeneutical tool to examine what can be learned about how Book of Mormon prophets may have understood the plan of salvation. Specifically, Jacob’s understanding of the plan of salvation will be analyzed by examining his writings in 2 Nephi 9–10. The evidence from this study suggests that some Book of Mormon prophets (at least Jacob and Nephi) viewed the plan of salvation through the lens of heavenly ascent.

In the text of the Book of Mormon, the various iterations of the term “plan of salvation” appear thirty times.1 This study asserts that a consistent paradigm was used by Book of Mormon authors to understand one element of the plan of salvation, namely heavenly ascent motifs. To investigate this thesis, a summary of key elements in heavenly ascent literature will briefly be examined. These elements will be organized into a model or lens that will be used as an interpretive tool throughout this paper. This overview of heavenly ascent will be followed by a synopsis of scholarly work that demonstrates similar heavenly ascent motifs in the Book of Mormon, providing plausible evidence that Book of Mormon authors were aware of this concept and used it in their writings and [Page 138]teachings. Jacob’s sermon in 2 Nephi 9–10 will then be examined using the concepts of heavenly ascent as a hermeneutical lens. Once accomplished, this analysis will be used to consider whether Jacob understood the plan of salvation through the lens of heavenly ascent.

Heavenly Ascent

Heavenly ascent, or celestial ascent, “is one of the most widespread and long-lasting religious concepts in history.”2 Examples of this phenomenon are widespread in the Jewish and Christian writings,3 as well as in other cultures and religions.4 This concept refers to the idea of a fallen mortal ascending back into the presence of God. This ascension can occur either in mortality or after death, as in the Final Judgement (2 Nephi 11:2–3, 28:23).5

Heavenly ascent as an umbrella concept incorporates several other experiences, such as theophanies, sôd experiences, Second Comforter experiences, and temple experiences. These distinctions will not be the focus of this paper. Instead, all these concepts will be broadly examined to understand the elements common to heavenly ascent in general.

Ritual ascent and heavenly ascent are closely related but are two different ideas. Hugh Nibley explained that “Heavenly ascent is the realization of ritual ascent.”6 One is the teaching or training to ascend (such as what occurs in temples) and the second is the actual act of [Page 139]ascension. While recognizing this technical difference between the two concepts, since the focus of this paper is on general motifs of ascension literature, both heavenly and ritual ascent will be considered in this study.

Heavenly ascent literature includes many elements, but general patterns may be detected in the literature.7 The specific pattern this paper will utilize is six-fold:

- [Page 140]The two-part structure

- Receiving light, knowledge, and mysteries

- Cleansing processes

- Prayer

- Angels or heavenly messengers

- The presence of God.

The Two-Part Structure: The Down-Road and the Up-Road

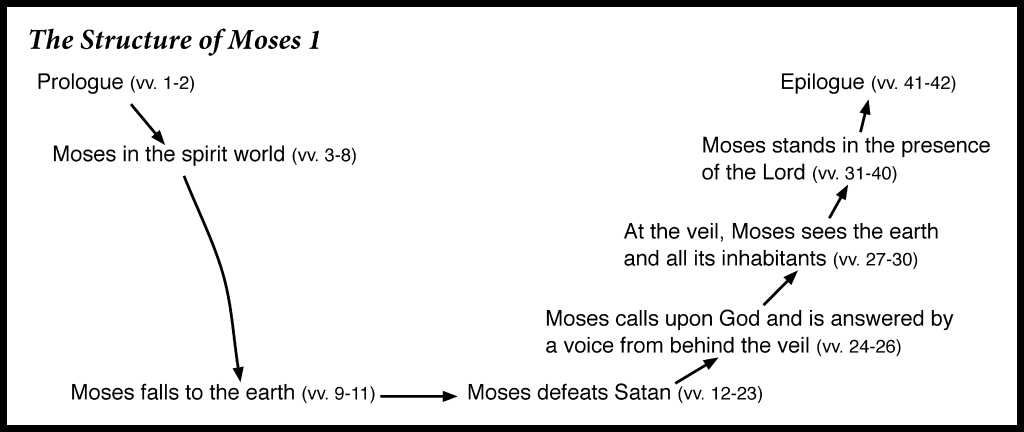

The first element is the overall structure of the accounts. Jeffrey Bradshaw explained, “Accounts of heavenly ascent and temple ritual are not uncommonly structured into two main parts: a ‘down-road’ followed by an ‘up-road.’”8 Bradshaw has shown how “consistent with this pattern, Moses 1 takes the prophet from a vision of his first home in the spirit world, then downward to the telestial world of the mortal earth, and, finally, upward in a step-by-step return to God. Moses’s experience culminates within the ‘heavenly temple,’ where he is shown a vision of the Creation, the Fall, and the essential role of the Atonement, as described in Moses chapters 2–5” (see Figure 1).9 These three terms — the creation, the fall, and the atonement — are referred to by Elder Bruce R. McConkie as “the three pillars of eternity” and are often used inside heavenly ascent literature to frame this two-part structure.10 For example, Baker and Ricks have explained that ritual ascent dramas once performed in Solomon’s Temple contained didactic elements that [Page 141]focused on these three pillars.11 In this two part-structure, the down-road consists of the creation and the fall while the up-road consists of the atonement.

Figure 1. The two-part structure in Moses 1.12

Receiving Light, Knowledge, and Mysteries

The second part of the six-part pattern is often connected to the two-part structure discussed above where “an upward physical movement often paralleled a ritual heavenly ascent from darkness to increasingly greater light.”13 This concept of light, which is pervasive in biblical and extrabiblical heavenly ascent literature, seems to be present in both the process and the culmination.14 For example, in Manichaean scripture and ritual, “The ‘descent of the First Man from the land of light,’ his redemption, and his return to the kingdom was a ‘favorite theme,’ [Page 142]and was ‘in a very real sense the story of each soul.’”15 As individuals progressed upward through different stages, they learned “mysteries” that allowed them to return to the “land of light” and receive a crown of glory (glory being associated with light in much of Jewish literature).16

Another example of light being connected to ascension is found in Enoch’s various ascents recorded in 1 Enoch and 2 Enoch where Enoch was “‘led forth into all secrets’ and shown ‘all secrets of righteousness.’”17 One such instance depicts when “Enoch the high priest figure has ascended through the heavens to stand before the throne” of God.18 During this experience, Enoch is dressed in “garments of glory” and anointed with “a fragrant myrrh oil,” which appearance was “greater than the greatest light.”19 Thus, a gradual process seems to generally occur in which a participant progresses upward through receiving light, knowledge, and mysteries until they are eventually brought back into the presence of God. This light and knowledge were reserved for the elect and could include things like God’s secret name.20

Cleansing Processes

The third part of the six-part pattern is some type of cleansing process that purifies an individual. “Candidates … were often required to further prepare for their ascent through fasting and ritual purifications” or risk being “dismissed from before the [celestial] throne [of God].”21 For [Page 143]instance, when Isaiah experienced his heavenly ascent, he worried about his unclean state before the presence of God (Isaiah 6:5).22 After the seraphim purged Isaiah’s lips with the coal from the altar, the prophet felt worthy to stand in the presence of God (Isaiah 6:6–7).23

Cleansing processes often included covenant-making motifs such as in Jacob’s vision of the ladder.24

Jacob saw a ladder on the earth, which reached to heaven. Ascending and descending on the ladder were the angels of God, sentinels to the portals of heaven. Above the ladder was the Lord Himself, whom Jacob heard and with whom he would make the very same covenant that his grandfather Abraham had made — the same covenant his father, Isaac, had prepared him to receive.25

In the pericope referred to in this quotation, it is implicit that making a covenant and being obedient to its conditions is a prerequisite for [Page 144]ascending to God’s presence (Genesis 28:13–15). At times, these covenants are entered into through the initiate’s participation in ordinances. For instance, in the Book of Moses, the narrative often “stops the historic portions of the story and weaves into the narrative framework ritual acts such as sacrifice, … ordinances such as baptism, washings, and the gift of the Holy Ghost; and oaths and covenants, such as obedience to marital obligations and oaths of property consecration.”26 Consistent faithfulness to covenants entered into through these ordinances cleansed an individual and was a part of the process of becoming adequate to see the face of the Lord.27

Prayer

The fourth part of the six-part pattern is prayer. After a person experiences the “down-road,” there is a separation between God and man. This separation is often attributed to the veil, which is a “a kind of ‘visionary screen’” that conceals the presence of God.28 In order to ascend back to God’s presence, this separation must be bridged through some method. One general pattern is that of an individual calling upon God through prayer, rending the veil, and standing in the presence of God.29

For instance, Bradshaw argued Job experienced an ascent in the Bible which included the use of “prayer circles” as a tool that helped [Page 145]“the hero meet the requirement to prove himself worthy of a continued journey toward divine light and knowledge.”30 This principle might also be observed in Isaiah’s ascension when, as pointed out earlier, he was worthy to be in God’s presence only after “one of the seraphs presses to his lips … ‘a live coal’ (Isaiah 6:6; 2 Nephi 16:6), presumably taken from the altar of incense (the only burning altar within the temple building and significantly symbolic of a kind of truer order of perpetual prayer offered up constantly before the temple’s veil).”31 Thus, it seems likely that prayer played an important role in the purging of Isaiah’s sins necessary for his ascent (Isaiah 6:7; 2 Nephi 16:7).32

Angels or Heavenly Messengers

The previous themes of cleansing processes, light/knowledge, and prayer/veil are often associated with the fifth part of the six-part pattern, which is the presence of angels or heavenly messengers.33 Angels are present several times in the Patriarch Jacob’s heavenly ascent experiences starting with his previously discussed vision of the heavenly ladder. In this revelation, Jacob saw “angels ascending and descending thereon and … realized that the covenants he made with the Lord there were the rungs on the ladder that he himself would have to climb in order to obtain the promised blessings — blessings that would entitle him to enter heaven and associate with the Lord;” however, these “great promises and blessings … were conditional rather than absolute.”34 The realization of these blessings would not occur until years later when Jacob was dealing with some intense struggles and praying for “greater light, knowledge, and power” (Genesis 32:9–13, 24–30).35 This needed endowment of power came to Jacob through another heavenly messenger who appeared to [Page 146]Jacob and wrestled with him throughout the night.36 The result of this battle was the “burst[ing] of the veil,” exposing an “ultimate theophany” in which Jacob was “privileged to enjoy the literal presence of God and to have every promise of past years sealed and confirmed upon him.”37

In addition to this function, it seems that angels play a role even after an individual enters the presence of God.38 Angels are often depicted surrounding the throne of God (see 1 Kings 22:19–23).39 This gathering is often referred to as a divine council and includes “the divine beings who compose God’s heavenly court.”40 When a person is introduced to [Page 147]this divine council, they “hear and see”41 a “theophany of Yahweh on his throne … and [are] subsequently … made aware of confidential heavenly secrets.”42 This experience is named after the divine governing council and is referred to as a sôd experience.43 These experiences generally also include elements such as being tested, praising God, singing, learning of mysteries, and a charge to teach others upon returning from the council.44 In some cases, accounts of sôd experiences include the participant speaking with the tongue of angels, joining the divine council, and even experiencing some type of deified status.45

[Page 148]Presence of God

The sixth and final part of the six-part pattern is the actual entering into the presence of God. This constituted a sort of reversal from the fall of Adam when mankind lost the presence of God.46 At times associated with some type of judgment motif, it is during this event that the divine and mortal are brought “face to face” and often share some form of conversation (see Genesis 32:30; Exodus 33:11; Abraham 3:11).47 In some heavenly ascent literature, God declares the ascended person’s salvation to be “made sure”48 during this conversation, and might even include some type of ordinance.49 Either way, this moment is the culmination of a process in which a person (or community) successfully climbed the “up-ward” road back to their original heavenly height.50

[Page 149]Heavenly Ascent Motifs in the Book of Mormon

The presence of heavenly ascent literature in the Book of Mormon should not be surprising considering that “the Book of Mormon is yet in many regards a book rooted in the ancient Near East.”51 As such, like the Bible and other Near Eastern texts, “the Book of Mormon provides a depiction of the divine council and narrates several instances where prophets were introduced into this assembly, made privy to heavenly secrets, and commissioned to preach their newfound knowledge to others.”52

Baker and Ricks have suggested that heavenly ascent motifs can be identified within individual works of the Book of Mormon such as in the teachings of King Benjamin,53 Abinadi,54 Alma,55 and Moroni.56 Moreover, Mormon organized the “entire Book of Mormon … [with a] carefully structured pattern” designed to teach readers about their ascent into the presence of God.57 He states, “I, Mormon, make a record of the things which I have both seen and heard, and call it the Book [Page 150]of Mormon” (Mormon 1:1). This phrase suggests that Mormon had entered into the divine council, enjoyed the presence of God, and was now commissioned to teach others about how to come unto the presence of God.58 This proposed mission for Mormon is congruent with one of Moroni’s closing exhortations that suggests that the agenda behind writing the Book of Mormon was to help readers accept the Savior’s invitation to “rend that veil of unbelief” and to see God “face to face” as Moroni and others in the book had done (Ether 4:14–15; 12:39, 41).59

In addition to the closing comments in the Book of Mormon, its opening comments regarding Lehi’s prophetic call could also be understood in heavenly ascent terms (1 Nephi 1:4–19).60 The account opens with Lehi praying to the Lord and a pillar of fire, or light, descending upon him (1 Nephi 1:5–6).61 During this experience, the scriptures record that Lehi “saw and heard much” (1 Nephi 1:6). After returning home, Lehi is “overcome with the Spirit [and] carried away in a vision” (1 Nephi 1:7–8).62 In the vision, Lehi sees “God sitting upon his [Page 151]throne, surrounded with numberless concourses of angels in the attitude of singing and praising their God,” a description clearly connected to divine council scenes in heavenly ascent literature (1 Nephi 1:8).63 Furthermore, scholars have suggested additional connections to heavenly ascent in this narrative include the moments when Lehi joins the heavenly host in praise and song (vv. 14–15),64 sees Jesus Christ with his twelve apostles and compares them to celestial lights (vv. 9–10),65 and receives a book from the divine messenger.66 Considering this, it is likely Lehi received a sôd experience during his multipart manifestation of the divine in which he became “a messenger sent to represent the assembly that had convened in order to pass judgment upon Jerusalem for a violation of God’s holy covenants.”67 Lehi would eventually fulfill this divine mandate in verse eighteen, which includes another occurrence of the phrase “seen and heard.”

Heavenly ascent motifs appear between Lehi and Moroni’s words as well. Helaman 10 may be just such a case.68 In this account, God addresses Nephi, the son of Helaman, in “the presence of mine angels,” suggesting the traditional divine council scene (Helaman 10:6). This heavenly court [Page 152]location seems to be confirmed by realizing that verse eight suggests Nephi has been transported to a new location, a temple. Furthermore, “this temple” in verse eight might be connected to “this mountain” in verse nine, further suggesting a much more divine geography because “exceedingly high mountain[s]” can be synonymous with the “heavenly temple, the traditional meeting place of God’s divine assembly.”69 During this experience, Nephi also receives a call to preach about what he saw and heard, which he accomplishes when he “‘did return unto the multitudes … and began to declare unto them the word of the Lord’ straightway after his theophany (Helaman 10:12).”70

The Brother of Jared’s Experience

The brother of Jared’s experience, recorded in Ether 3, is yet another example of heavenly ascent motifs. The Jaredite account begins with the people being removed from the presence of God with the rise of the Tower of Babel. The brother of Jared and his companions quickly start their trek back into the presence of God through separating themselves from wickedness (Ether 2:1) and offering frequent prayer to God (Ether 1:34, 36, 38; 3:1).71 Eventually, the brother of Jared’s spiritual ascent is matched with his physical ascent into a mountain, where, after the prophet recognizes his unworthiness as Isaiah did, the Lord asks him certain questions, gives him light, extends his hand/finger through the veil, and receives the brother of Jared into his full presence (Ether 3:2, 6).72

The Lord accomplishes this by first showing his hand to the brother of Jared and then by beginning a line of questioning aimed at testing the prophet of which Moroni “could not make a full account of” (Ether 3:17, 21–22). After passing this test, the brother of Jared receives information: “these words” in verse thirteen that the Lord said he “shall speak” in [Page 153]verse eleven, which included some type of incredible knowledge that fully opened the veil for the prophet. The description of this knowledge remains absent in the text (Ether 3:17–20). This fact is additional evidence of this being a heavenly ascent because the knowledge given by God in these types of accounts should remain an esoteric mystery to the uninitiated reader until they themselves ascend to God’s presence.

While this account lacks any direct acknowledgment of a divine messenger (other than Christ himself) or divine council, it does not necessarily preclude the possibility that those elements are present but unmentioned. Furthermore, the signal phrase of “seen and heard” appears twice in verse 21 describing the brother of Jared’s experience. Therefore, considering this evidence and the presence of other important heavenly ascent motifs in this account, this account remains an excellent example of heavenly ascent literature in the Book of Mormon.

Nephi, son of Lehi, and Heavenly Ascent

Any discussion of heavenly ascent motifs in the Book of Mormon would be incomplete without considering the work of Nephi, son of Lehi. Because of the excellent example of heavenly ascent motifs it contains and its importance to the remainder of this paper, a synopsis about this work has been saved until now.

Nephi “begins [his record] with a colophon, introducing himself and his reasons for making his record.”73 In this colophon, “Nephi says he ‘had a great knowledge … of the mysteries of God.’ The very next statement from Nephi is ‘therefore, I make a record of my proceedings in my days’ (1 Nephi 1:1), meaning that his knowledge of the mysteries is Nephi’s justification for making a record.”74 Rappleye explains, “The term mystery comes from the Greek μυστήριον (mystērion). … ‘The connection of the prophets with mysteries dates back to the role of the prophet as witness in the heavenly sôd where he heard the secret counsels of God and conveyed them to men.’”75 Thus, Nephi is essentially claiming that he is a “true prophet”76 who has ascended to God’s presence and is now writing a record to teach readers how to receive their own sôd [Page 154]experience.77 This understanding significantly colors certain statements made by Nephi with heavenly ascent undertones as when he wrote, “For the fulness of mine intent is that I may persuade men to come unto the God of Abraham” (1 Nephi 6:4). In this light, “to come unto God” means to literally enter the Lord’s presence.

Nephi’s claim to know the mysteries previously discussed is arguably derived from events that occur in 1 Nephi 11 when Nephi, after “hear[ing] all the words of my father … was desirous also that I might see, and hear, and know of these things” (1 Nephi 10:17; see also 1 Nephi 9:1).78 The vision begins with Nephi being “caught away in the Spirit of the Lord, yea, into an exceedingly high mountain” (1 Nephi 11:1). This description “shares much in common with traditional Near Eastern imagery concerning the divine assembly and invocation of heavenly beings as council witnesses.”79 On the mountain, Nephi was interviewed by the Spirit of God (1 Nephi 11:4). Judgement scenes like this are common in heavenly ascent literature. In this example, Bokovoy explains that by taking on this role of inquisitor, “the Spirit of the Lord … assumed the traditional role of temple priest/guardian, [and] Nephi was able to receive the greater light and knowledge he desired on the mountain of [Page 155]God.”80 After this interaction, Nephi was then inducted into similar, possibly even identical, mysteries as his father (1 Nephi 11:1).81

Nephi likely used this knowledge to structure his final thoughts in 2 Nephi 31–32. In these two chapters Nephi teaches readers how to return to the presence of God themselves by following a pattern of exercising faith; repenting; being baptized; receiving the Holy Spirit, light, and knowledge; praying; hearkening to the voice of angels; and then entering the presence of God.82 Spencer refers to this process as “angelicization” and argues that Nephi is modeling this process after Lehi’s ascent to the divine council.83 In essence then, Nephi is promising “that the obedient can, as Lehi had done, join the angelic council”84 and become saved in God’s presence.85

Rappleye suggests that Nephi’s closing remarks are also connected to this heavenly ascent agenda. When Nephi bids farewell to his readers by declaring his words to be the word of God and promising that he will be present at their judgement day, he is essentially claiming to be a part of the divine council (2 Nephi 33:10–11; see also 2 Nephi 32:3).86 [Page 156]Thus, Nephi concludes by confirming his sôd experience and testifying that “the scriptures” that he “write[s]” and “delighteth in,” are simply the record of “the things which I have seen and heard” in his heavenly ascent (2 Nephi 4:15–16). If readers want to be saved in the presence of God, as he and his father were, Nephi witnesses that they must follow his heavenly ascent pattern presented in 2 Nephi 31–32.

Examining 2 Nephi 9–10 through the

Hermeneutical Lens of Heavenly Ascent

The manifestation of God in heavenly ascent results in what Nephi and other Book of Mormon prophets understood as salvation, or in other words, redemption from the fall of Adam back into the presence of God (2 Nephi 31:15–16, 21; see also 1 Nephi 15:14; 2 Nephi 1:15, 2:2–10, 26; Alma 58:41; Helaman 14:14–18; Ether 3:13–14).87 Thus, if heavenly ascent is synonymous with redemption, then the plan of redemption in the Book of Mormon is synonymous with the motifs of heavenly ascent.88 Though certain scholars have touched on this connection, there has been no study to date that has rigorously examined Book of Mormon sermons to verify this statement.89

[Page 157]This paper fills this gap in the research by offering a hermeneutical approach of how to examine sermons in the Book of Mormon to identify if its prophets shared a common heavenly ascent paradigm when discussing the plan of salvation. This will serve as a model for other sermons to be likewise examined in future studies. For now, this section will analyze portions of Jacob’s writings in Second Nephi to discover if he might have used heavenly ascent motifs to understand the plan of salvation. After this analysis of Jacob’s sermon, a discussion of the data collected using this interpretive technique will be completed with suggestions for further research.

2 Nephi 9–10 Overview

Jacob’s words in 2 Nephi 9–10 are part of a larger two-day discourse. Although the setting for this event is unknown, it is likely that it occurred in connection with the Nephites’ recent exodus fleeing the Lamanites.90 Additionally, certain scholars suggest this sermon was given in relation to “a covenant-renewal ceremony during the Feast of the Tabernacles (Sukkot).”91 This is significant because other scholars claim that an “operetta-like play” containing extensive heavenly ascent motifs was anciently associated with this festival.92 If Jacob was speaking during [Page 158]the Feast of the Tabernacles, the possibility of his sermon containing heavenly ascent themes might comfortably situate it within an ancient Israelite context.

While not all of Jacob’s words are recorded (2 Nephi 11:1), Jacob appears to be addressing the Nephites’ mentality that they have been removed from the promises of God.93 In this two-day discourse, Jacob quotes from passages of Isaiah (Jacob 6–8) and then provides his personal commentary on those pericopes (2 Nephi 9–10).94 He teaches the people about death and hell and about how the Atonement of Jesus Christ overcomes these barriers. He wants the Nephites to know that “the promises made to the general Israelite community still apply to them as well.”95 Though they have been driven out of past lands of inheritance, the land they currently live on will be their land of inheritance (2 Nephi 10:10, 19–20). Thus, the promises of the Abrahamic Covenant still apply to them (2 Nephi 9:20–22).96

Heavenly Ascent Motifs in 2 Nephi 9–10

2 Nephi 9–10 will now be examined through the hermeneutical lens of the six-part heavenly ascent pattern discussed earlier. In the beginning of his remarks, Jacob explains that he has chosen to quote Isaiah so that the audience might “know concerning the covenants of the Lord that he has covenanted with all the house of Israel” (2 Nephi 9:1). These covenants [Page 159]Jacob is speaking about refer to the Abrahamic Covenant, which was promised to Abraham and to his posterity (2 Nephi 8:2; Abraham 2:9– 11). These covenants were renewed with the entire community of Israel at Mount Sinai (Exodus 19:5–7, 24:7–8).97 In his speech, Jacob explains the purpose of these covenants were to restore the people to “lands of inheritance” and to “the true church and fold of God” (2 Nephi 9:2).98

It is likely these covenants and the two purposes outlined by Jacob carried with them the understanding of promises of heavenly ascent given that Abraham was experiencing a theophany during the making of this covenant (Genesis 15:1, 17:1; Abraham 2:6).99 When the same covenant is made with Abraham’s grandson, Jacob, it is likely he also receives a theophany (Genesis 28:12–20, 24–30).100 Additionally, the renewal of this covenant with the community of Israel at Mount Sinai is also connected to a theophany for Moses (Exodus 19).101 Jacob’s opening [Page 160]remarks might have been crafted to signal to the attentive listener to expect heavenly ascent motifs in his following remarks. If correct, this significantly affects how one should understand Jacob’s teaching that, “nevertheless, in our bodies we shall see God” (2 Nephi 9:4). Rather than only referring to a post-death manifestation of the Master, Jacob might also be referring to a visitation from God while in mortality– like Abraham, Jacob, and Moses experienced.

Following his opening remarks, Jacob immediately describes the two-part structure found in heavenly ascent literature. He first references Jesus Christ as “the great Creator,” then repeats this title in the next verse and explains that this Creator has a plan for mankind (2 Nephi 9:5–6). In connection to verse five, verse six and seven summarize this plan as including the creation, the fall of mankind, and then the infinite atonement. This model, then, portrays a person’s descent through the creation and fall pattern and then a person’s ascent through the atonement, which brings mankind back into “the presence of Lord” from which they were “cut off from” due to the fall (2 Nephi 9:6–7).102 Hence, Jacob seems to be introducing the plan of salvation in heavenly ascent terminology.

Jacob then begins to outline two directions a person might take at the low point in the two-part structure. The first, rather than a heavenly ascent pattern, could be termed a “hellish descent” pattern because of a person’s further descent away from God when following this path (2 Nephi 9:9–10). Because of its antithetical nature, this negative pattern will be discussed later in this paper. Jacob’s second direction follows [Page 161]a heavenly ascent pattern. This path “prepareth a way for our escape” from the first pattern and is the great “plan of God” and “the way of deliverance of our God” (2 Nephi 9:10–11, 13).103

The succeeding verses continue Jacob’s discussion about the resurrection, and its role in bringing mankind back into the presence of God (2 Nephi 9:11–24).104 One can find several heavenly ascent motifs in this section. For instance, when a person is resurrected and in the presence of God, the participant receives special “knowledge” or “perfect knowledge” (2 Nephi 9:13–14). This type of knowledge could also be similar to the phrase Jacob uses in the next chapter–true knowledge (2 Nephi 10:2). In that instance, this special knowledge refers to a “knowledge of their redeemer,” argued later in this paper to mean a physical experience with the Lord’s presence.105 Thus, the knowledge in 2 Nephi 9:13–14 might very well be associated with the mysteries received in sôd experiences or, in the very least, consciously designed to be redolent of it.

This resurrection scene describes another motif that is common in heavenly ascent literature: judgment scenes. An example of this is Nephi’s cross-examination in 1 Nephi 11:4. Such judgement scenes in heavenly ascent literature provided a method for the initiate to prove worthiness.106 Judgment is an important motif in Jacob’s sermon [Page 162](appearing multiple times) and is also tied to people being worthy of the presence of God (2 Nephi 9:7, 15, 22, 44, 46).107

In connection to the idea of proving worthiness, Jacob’s resurrection/ judgement scene also correlates with another heavenly ascent motif: a cleansing process. The special knowledge Jacob mentions in relation to the judgement makes the resurrected being aware of their guilt or righteousness before God (2 Nephi 9:13–14). This is resonant of the biblical scene when Isaiah suddenly recognizes his state of uncleanliness during his heavenly ascent (Isaiah 6:5). Like Isaiah’s “live coal” that cleanses his lips (Isaiah 6:6), Jacob explains that to be “clothed with purity” one must “repent, and be baptized in his name, having perfect faith in the Holy One of Israel” (2 Nephi 9:14, 23–24). Once cleansed in this manner, a person is not only worthy of entering the presence of God but also of “inherit[ing] the kingdom of God” (2 Nephi 9:18). These verses, therefore, contain Jacob’s warning of the reality of a heavenly ascent and the dangers of entering God’s presence without previously cleansing oneself appropriately.108

Death, Hell, and the Temple-Oriented New Year Feast

The outcome of this cleansing pattern is to destroy two enemies: death and hell. First referenced in verse ten, this duet is a major theme of Jacob’s sermon. In fact, 2 Nephi 9 “contains more references to hell than any other chapter in all scripture.”109 One reason this is significant is because of the connection of this duet to a pre-exilic, “temple-oriented New Year festival.”110 The theory of this pre-exilic, temple-oriented festival [Page 163]has been present in scholarship since the late nineteenth century.111 Hugh Nibley was the first Latter-day Saint scholar to employ this idea.112 Basically, this argument claims that associated with the temple there was a ritual drama that consisted of a “dramatic representation of the full eternal sweep of the powers of the Savior’s Atonement,” and that it “was originally the focal point of the Law of Moses.”113 The Israelites would “ritually reenact the story of their origins and purposes with a drama that included a remaking of their earlier ordinances and covenants.”114 This ritual ascent mirrored the heavenly ascent ending with a person’s reconciliation with God and becoming a king and priest.115

To assure the participants of their ability to accomplish this divine odyssey, the drama promised “that Jehovah himself [would] avert the king’s difficulties–even to defeating the ultimate enemies, death and hell– to save the king and his people.”116 This was a major theme of [Page 164]the ritual and allowed the initiate to ascend to “the cosmic temple.”117 In fact, as the festival ritual came to a conclusion, there “was a celebration of Jehovah’s ultimate triumph over evil, and of his creation of a new and wonderful world of peace and harmony.”118 This imagery juxtaposes the evil of death and hell with the creation story.119 Interestingly, “Throughout the ancient Near East, a common variation on this narrative was to personify the precosmic ocean, characterizing it as a serpent or monster, transforming the creation process into a battle between God, the Creator, and chaos, the monster.”120 Thus, Jehovah was often seen by the Israelites as a divine warrior who battled this monster of death and hell.121

It is plausible that Jacob could be consciously using the motifs of this drama in his sermon because the ritual was being celebrated at the same time as the delivery of 2 Nephi 9. Thus, when Jacob refers to the Savior’s victory over death and hell, it is probably not a coincidence that this motif is identical to heavenly ascent narrative of the pre-exilic drama. Even Jacob’s use of the term monster in describing death and hell ties perfectly well within the festival drama (2 Nephi 9:10, 19, 26). This monster parallels the drama’s concept of chaos, described by Jacob as “experiencing … death without the mediation of the atonement.”122 Jacob adds that, when Christ overcomes this monster, mankind inherits a new world–the kingdom of God (2 Nephi 9:18). This is strikingly like [Page 165]the end of the temple drama when Christ triumphs over evil and creates “a new and wonderful world of peace and harmony.”123

Day of Atonement and Nephi’s Sermon in 2 Nephi 31–32

There are more heavenly ascent motifs contained in 2 Nephi 9, but to appreciate their significance a basic review of the Day of Atonement, of Nephi’s sermon in 2 Nephi 31–32, and of the heavenly ascent agendas of these two things must be discussed.124 The Day of Atonement, or Yom Kippur in Hebrew, is a ritual ascent festival celebrated in Judaism on the tenth day of the seventh month of the Jewish calendar.125 It is considered by Jews to be the holiest day in their calendar because it offers them atonement, meaning “the end of estrangement and the return to perfect unity” (Leviticus 16:16).126

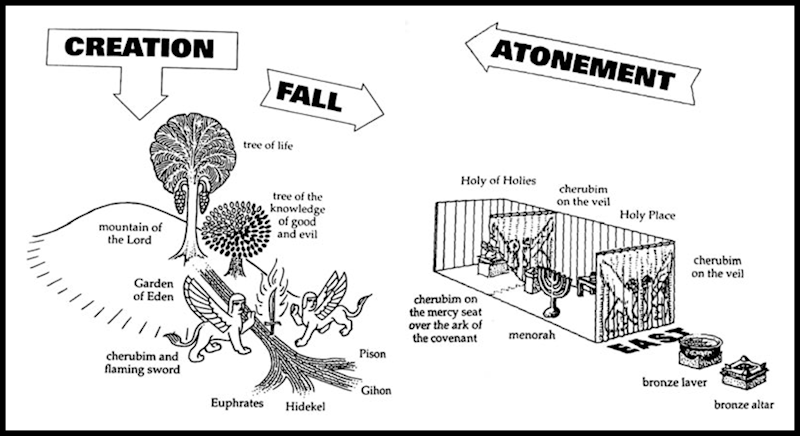

The need for a Day of Atonement “begins in the garden of Eden, where God seems to reside, as he is seen walking and relating intimately to Adam and Eve. Disobedience and sin cause them to be driven from [Page 166]the garden and the presence of God (Genesis 1–11)” (see Figure 2).127 However, the covenantal relationship of the people of Israel, along with the liturgy of the tabernacle, made it possible for God’s presence to once again be available to the people.128

This was the point of the Day of Atonement:

Once a year on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, Adam’s eastward expulsion from the Garden is reversed when the high priest travels west past the consuming fire of the sacrifice and the purifying water of the laver, through the veil woven with images of cherubim. Thus, he returns to the original point of creation, where he pours out the atoning blood of the sacrifice, reestablishing the covenant relationship with God.129

Thus, this ritual ascent “was the acme of all temple rituals” because it was a day of purification that ritually reconnected the Israelites with God and brought them back into his presence.130 A simplified illustration of this ascent is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Concepts of the creation, fall, and atonement help demonstrate the purpose of the Tabernacle to bring participants back into the presence of God.134

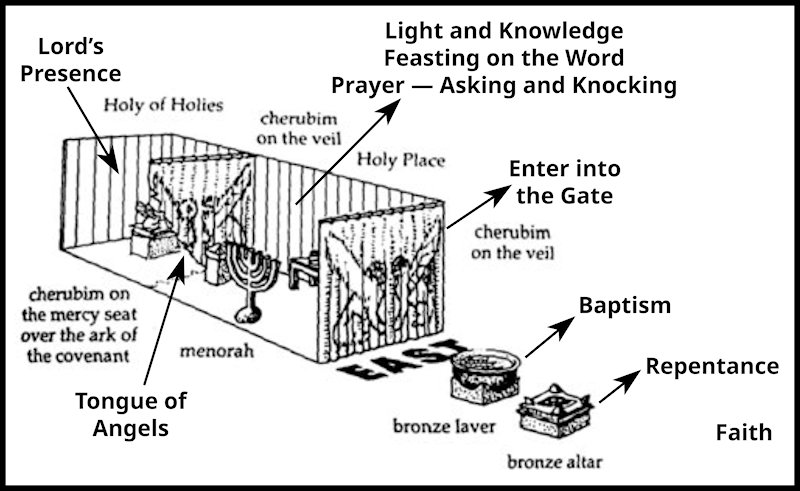

As discussed previously, Nephi is likely utilizing this festival in his sermon contained in 2 Nephi 31–32.131 Hopkin argues there is a connection between Nephi’s description of the doctrine of Christ and the high priest’s ascent through the temple during the Day of Atonement by pointing out direct parallels between the two ideas.132 Nephi was rhetorically “provid[ing] [his audience] with a familiar context by describing them in terms provided by the Temple of Solomon.”133 Thus, [Page 167]Nephi’s doctrine of Christ parallels the high priest’s ritual ascent in the Day of the Atonement (see Figure 3). By “moving by faith or real intent to and then past the altar of sacrifice, which Jesus states is the sacrifice of a repentant, ‘broken heart and contrite spirit’ (3 Nephi 9:20)”135 a person begins the process of entering the presence of God. After faith and repentance, a person is baptized which is associated here with the laver of water.136 This leads a person to “the gate by which (they) should enter” (2 Nephi 31:17) which in this paradigm is the entrance to the Holy Place of the tabernacle.

Figure 3. Demonstrating how the doctrine of Christ overlaps with the structure of the Tabernacle.138

Once inside the Holy Place, there are certain objects that might correspond to what Nephi wants his readers to do “after ye have gotten into this strait and narrow path” (2 Nephi 31:19). The Menorah, with its blazing light, relates well to receiving “the baptism of fire and see[ing] by the light of the Holy Ghost.”137 Another connection can be found in [Page 168]the table of shewbread and its bread and wine. “This bread and wine provide a communal feast with God, symbolizing the strengthening power of the word of God … to move forward in the name and power of Christ.” 139 This is directly connected to Nephi’s concept of feasting on the word of God and enduring to the end (2 Nephi 31:20).140 The second to last symbol is the altar of incense, which symbolizes “the prayers of all God’s people” (Revelation 8:3; see also Luke 1:10). The altar of incense [Page 169]connects to Nephi’s instruction that praying, asking, and knocking leads a person to the veil of God. Embroidered on this veil were two cherubim, suggesting that a person must interact with angels (i.e., speak with the tongue of angels) to come into the presence of God, which was symbolized by the Holy of Holies.141

In Nephi’s sermon, the worshipper is left before the veil in the Holy Place “seeking to speak the tongue of angels by a reliance on the word of God and the gift of the Holy Ghost.”142 This is noteworthy because the phrase “tongue of angels” is Nephi’s way of inviting readers to ascend to a sôd experience and, as the angels do, sing and praise the name of the Lord.143 Thus, what Nephi is doing is using the ritual ascent of the Day of Atonement to promise readers “if the worshipper will endure appropriately, it is possible to pass through the veil, enter into [the divine council], seeing [God] in the flesh, face to face” (2 Nephi 32:6).144

Continuing the Approach Towards the Presence of God in 2 Nephi 9

The model Nephi uses in 2 Nephi 31–32 can help readers identify the heavenly ascent motifs inside Jacob’s work in 2 Nephi 9. The fact that chapter nine comes first could lead a reader to conclude that the latter chapters might be referring to the first. However, there are several problems with this simple analysis. First, it is unclear chronologically when either of these sections were created in relation to the other. [Page 170]Nephi’s teachings in 2 Nephi 31–32 could have previously been given to the Nephites. Jacob could be quoting his brother’s thoughts and Nephi simply re-recorded or included them later while writing his book. Because of this ambiguity, this paper examines the intertextuality without a stance on which author is building off the work of the other.

Jacob’s cleansing process–faith, repentance, baptism, receiving the Holy Ghost, and enduring to the end (2 Nephi 9:23–24) — is identical to the one Nephi describes in 2 Nephi 31–32. Jacob is using the identical pattern to help listeners accomplish the same heavenly ascent agenda Nephi describes. Note, also, the emphasis on heeding Jacob’s “words” which are also the “words of your maker” and the “words of truth” (2 Nephi 9:40). Three times, Jacob stresses the importance of remembering these words (2 Nephi 9:44, 51–52). Significantly, “remembering the word” is associated with the concept of feasting on things which “perisheth not, neither can be corrupted” (2 Nephi 9:51).145 In this sermon, Jacob associates perishing (2 Nephi 9:28, 30–32) and corruption (2 Nephi 9:7, 13) with the presence of the monster and the devil. He is unfolding the process that leads to the presence of the Lord. Thus, Nephi’s heavenly ascent design in 2 Nephi 31–32 finds an echo in Jacob’s association of feasting and heeding the word of the maker to come unto God.

The intertextuality of 2 Nephi 9:50–51 supports this conclusion. Following Jacob’s previous precedent, this pericope is a quotation from Isaiah 55:1–2.146 These verses introduce a chapter that is “an invitation to redemption,” focused on covenant making and “seek[ing] ye the Lord” (Isaiah 55:3, 5)–themes clearly connected to the Day of Atonement [Page 171]imagery.147 This Old Testament chapter contains the admonition to “come” seven times, with the overt purpose of “com[ing] unto me” (i.e., the Lord) (Isaiah 55:1, 3, 10, 13). Isaiah’s message noticeably parallels Jacob’s, which is the invitation to “come unto the Lord, the Holy One” and to “come unto that God who is the rock of your salvation” (2 Nephi 9:41, 45; see also v. 51).

This thought becomes more significant when connected with Baker’s and Ricks’ claim about the Feast of the Tabernacle drama that, “The ‘power of his redemption’ is the power to bring us back to him. In much of the Book of Mormon the realization of the drama’s crescendo–to become a son and heir of God, and return to his presence–is encapsulated in the single word ‘redeem.’”148 The idea of redemption and its heavenly ascent undertone connects both the plan of salvation and Isaiah/Jacob’s invitation to come unto Christ: “If to be redeemed means to be brought into the presence of God, then the phrase ‘plan of redemption’ means the plan whereby one can be brought back into God’s presence and has the same connotation as the frequently repeated invitation to come unto Christ.”149 Interpreting 2 Nephi 9:50–51 with this in mind, Jacob could be using Isaiah’s words to invite his listeners to enter a covenantal and redemptive relationship by feasting on the word of God, which would result in ascending into the presence of the Lord.150

This thought mirrors both of Nephi’s previously discussed writings with sôd experiences in general. Given that Nephi’s invitation to “come unto the God of Abraham” has heavenly ascent undertones (1 Nephi 6:4), consider how in 2 Nephi 31–32 Nephi connects “feasting upon the word of Christ” as part of the process that leads to God’s presence. The intertextuality between these two phrases and the text in 2 Nephi 9 was likely not lost on Jacob if Nephi’s work preceded his own (2 Nephi 31:20, 32:3). For instance, when comparing Jacob 9:50–51 with Isaiah 55:1–2, the most significant redaction Jacob makes is his replacement of Isaiah’s phrase “and eat ye that which is good” with a phrase very reminiscent of Nephi’s two phrases just discussed: “and come unto the Holy One of Israel, and feast upon that which perisheth not, neither can be corrupted.” [Page 172]Jacob might be stressing the heavenly ascent nature of this invitation by using more overt terminology that Nephi also uses to describe heavenly ascent motifs. Furthermore, this overt terminology could also be seen as describing the bowl of manna kept inside the ark of covenant in the Holy of Holies (Hebrews 9:4). Unlike the daily manna, this manna did not perish or become corrupted (Exodus 16:15, 20–21, 32–35). If this connection was intentional, Jacob could have been tying Nephi’s concept of feasting with the bowl of manna and to the Holy of Holies, which represented God’s presence and the climax of the ritual ascent in the tabernacle.151

Nephi says feasting on the word will “tell you all things what ye should do,” a phrase that implies acting on the invitation to feast on the word and come unto Christ will introduce a person to knowledge not previously known. Nephi also connects this process to angels and their instructions (2 Nephi 32:3). By using the term “feast,” Jacob is carefully inviting readers to seek out additional light and knowledge with the goal of literally seeing God, just like Nephi and other authors of heavenly ascent literature invited their readers to do.

Nephi’s admonition to “ask” and “knock” in search of more light is echoed in Jacob’s words that “whoso knocketh, to him will he open” and the things “hid from them forever” will be revealed unto them (2 Nephi 32:4, 9:42, 43). This is also reminiscent of the heavenly ascent motif of special or hidden knowledge that is revealed to those who are involved in sôd experiences. In addition to this, engaging in this process himself has led Jacob to “praise the holy name of my God,” a phrase strikingly suggestive of sôd experiences in which the initiate joins the heavenly council by singing and praising the Lord.

Even the idea of God’s holy name suggests Jacob might be speaking in heavenly ascent terminology where participants often seek after and learn “the secret name of God.”152 In Jacob’s sermon one of the reasons he explains for giving his sermon is so “that ye may learn and glorify [i.e., praise] the name of your God” (2 Nephi 6:4). Note first the concept of learning the secret name of God and second the concept of praising it. Jacob’s frequent use of the idea of God’s name might be Jacob’s [Page 173]way of declaring his special knowledge received from a divine council experience (2 Nephi 9:23–24, 41, 49, 52).

If Jacob has joined the divine council, then Jacob’s sermon along with his covenantal action153 to shake his garments as a witness to “the God of my salvation” fulfills his mission to declare unto the people what he had “seen and heard” as a commissioned member of God’s court.154 Additionally, the very act of drawing attention to his garment might allude to heavenly ascent motifs. The Day of Atonement immediately precedes the Feast of the Tabernacles, during which Jacob is apparently speaking.

According to the Lord’s instruction in Leviticus concerning the Day of Atonement, the high priest was to “wash his flesh in water” and then to “put on the holy linen coat,” “linen breeches,” “a linen girdle,” and a “linen mitre” (Leviticus 16:4). While wearing these garments, the high priest was to make atonement for himself, the temple, and the people by sacrifice (see Leviticus 16:33). During the ceremony, the high priest and priests were instructed on numerous occasions to remove their garments, wash themselves, and wash their clothes (see Leviticus 16:23–24, 26, 28).

Such emphasis on garments being kept clean (for example, from the blood of the sacrifices) in connection with the temple and the Day of Atonement may have inspired Jacob to take off his garments and display them before the Nephites. … This theme is further supported Jacob’s reference to “being clothed with purity, yea, even with the robe of righteousness” (2 Nephi 9:14) and by Isaiah passage Jacob quotes: “Awake, awake, put on thy strength, O Zion; put on thy beautiful garments, O Jerusalem, the holy city; for henceforth there shall no more come into thee the uncircumcised and the unclean” (2 Nephi 8:24, parallel to Isaiah 52:1).155

This assertion not only ties Jacob’s words to the New Year festivals, but also associates Jacob’s message with heavenly ascent motifs. Consider the garment as a representation of the high priest’s ritual ascent into the Lord’s presence. By Jacob connecting his garment with the high priest’s, he could have been alluding to his own heavenly ascent experience. Just [Page 174]as the high priest had to cleanse his garments for his ascent, so Jacob could be leaning on the imagery to claim that he had cleansed his own garments by the process described in verses twenty-three and twenty-four (the doctrine of Christ). Thus, Jacob’s garment could have been a symbol of his heavenly ascent.

One final way Nephi’s sermon might help us understand the heavenly ascent nature of Jacob’s discourse is to pay attention to how both authors choose to make their closing remarks. Just as prayer–represented by the altar of incense–is the last symbol in the tabernacle before approaching the veil and prayer is the last idea Nephi discusses in chapter thirty-two, prayer is one of the last topics mentioned by Jacob in his closing remarks for his sermon in chapter nine. He invites all listeners to “pray unto [God] continually by day, and give thanks unto his holy name by night” (2 Nephi 9:52). Nephi does not use the word “continually” as Jacob does, but the elder brother does instruct his readers to do something of an equivalent nature, to “pray always” (2 Nephi 32:9). This act of supplication to the Lord fits perfectly within heavenly ascent motifs where prayer is used to help an individual part the veil and enter into the presence of God. It is fitting, then, that Jacob ends the day by reminding all who listened to him about the covenants and condescension of the Lord, two phrases that echo Nephi’s writings describing his own sôd experience and that are perhaps used by Jacob to suggest the possibility to anyone listening of having a similar ascent experience (1 Nephi 11:16; 13:23, 26, 30; 14:5, 8, 14, 17; 15:14, 18; see chapter 11–15).156

Hellish Descent Opposed to Heavenly Ascent

Instead of ascending into God’s presence after the low point of the two-part structure, a person can make a “hellish descent” into the presence of the devil. The themes of heavenly ascent become reversed so a list of them would include concepts like disbelief, sin, darkness/ knowledge being hidden, demons/angels of the devil, and the presence of the devil/hell.157 The presence of both patterns suggests the author is consciously using a heavenly ascent paradigm to describe the path a person can choose in his or her life.

In Jacob’s writing in 2 Nephi 9, these two choices first appear in verses four through six when “see[ing] God” is juxtaposed with being “cut off from the presence of the Lord” because of subjection to the [Page 175]devil. The outcome of this subjection, or hellish descent, is “corruption,” “misery,” and “darkness” (2 Nephi 7, 9) instead of “mercy,” “joy,” and “life eternal” (2 Nephi 9:53, 18, 39). Jacob explains that the devil himself experienced this hellish descent, falling from the presence of the Lord and becoming the devil (2 Nephi 9:8). According to Jacob, this is the outcome for anyone who chooses a similar path. In contrast to heavenly ascent, hellish descent seeks after “secret works of darkness” rather than hidden truths of light and is rewarded with “secret combinations” instead of heavenly mysteries (2 Nephi 9:9). An additional comparison can be found in the observation that, like God, the devil employs “angels” to entice individuals along their paths. However, the devil’s angels lead a person down a path that aims to “shut out [people] from the presence of our God” whereas God’s angels bring people to the presence of God (2 Nephi 9:9, 16).

Jacob also includes a process for hellish descent that contrasts with the cleansing process of heavenly ascent. Rather than faith in God’s word and repentance when one falls short, hellish descent encourages “hearken[ing] not unto the counsel of God” and acting on sinful desires (2 Nephi 9:27–28). The “wo” verses in 2 Nephi 9:30–39 contain a sample of actions that one may take to continue being cut off from God’s presence rather than entering it through a cleansing process. Welch has argued that the ten woes reflect the Ten Commandments in Exodus 20.158 If true, the woes stand in direct opposition to the Sinai covenant, discussed previously as heavenly ascent literature. Either way, Jacob is clear: if his audience act on this list of woes rather than the cleansing process contained in verses twenty-three and twenty-four, “they must be damned” (2 Nephi 9:24; see also verses 46–48).159 Instead of the people entering a covenantal relationship (the token of which is circumcision according to Genesis 17:11), the people become “uncircumcised of heart” and lose their standing with God (2 Nephi 9:33).160 By frequently [Page 176]returning to the opposing outcomes of each path, Jacob is using hellish descent to emphasize the superiority of the heavenly ascent pattern and to motivate listeners to experience an ascent to God’s presence for themselves.

Jacob’s Sermon on Day Two

In 2 Nephi 10, “Jacob reprises the salvation theme of the prior day’s sermon,” but now focuses the salvation more on physical or geographic terms than spiritual terms.161 Jacob appears to have planned on the previous day’s discussion about obtaining a spiritual or heavenly land of inheritance (i.e., eternal life in God’s presence) to have built confidence in his listeners about the promises of a physical land of inheritance. In other words, if Jacob could convince his listeners that the first was possible, maybe the second topic would seem more attainable.

In addition to this, in 2 Nephi 10 there seems to be other aspects of the relationship between the spiritual and physical promises of the covenant that Jacob is attempting to address. One hint of this is in the realization that the objective of the geographical side of “the promises” mentioned in 2 Nephi 10:2 is to “give [the Nephites] the true knowledge of the Savior” (a very spiritual outcome). Thus, just as the spiritual promises might have positively affected Jacob’s listeners to trust in the geographical promises, the geographical promises might have positively affected the spiritual promises by providing a means that they might be accomplished.

Nevertheless, the purpose for the sermon on the second day was to teach the Nephites how God has “covenanted with their fathers that they shall be restored in the flesh, upon the earth, unto the lands of their inheritance” (2 Nephi 10:7).162 This promise includes those who are “dispersed” on “the isles of the sea,” which Jacob emphasizes includes the Nephites by repeating four times “this land” in his speech and then finally declaring “we are upon an isle of the sea” (2 Nephi 10:10– 12, 19, 20). Thus, though the Nephites feel “put … away” and “cast … off forever” (2 Nephi 7:1), Jacob assures them that God “still watched over them, and that therefore the covenant promises would still [Page 177]be met.”163 This assurance “would have provided the community [with] the faith necessary to establish a new home in this wilderness.”164

Yet, even while focusing on the promised blessings of a physical land of inheritance, Jacob still couches his message within heavenly ascent motifs. Following his previous day’s sermon in which he discussed angels enticing people down a hellish descent (and, by implication, heavenly angels helping people experience heavenly ascent), Jacob begins this sermon with the words from an angel of God (2 Nephi 10:3). One implication of this could be that though the message might directly focus on the physical scattering and gathering of the people from and to the land of inheritance, the purpose of the message is much more spiritual and divine in its objectives.

Another example of this couching in heavenly ascent motifs is how the Nephites’ physical scattering due to being “driven out of the land of our inheritance” (vv. 6, 20) is associated in this chapter with the people’s sins (sins being an obvious influencer of a person’s spiritual status in their heavenly ascent journey) (2 Nephi 9:20). For the physical gathering to succeed, “secret works of darkness” “must needs [be] destroy[ed]” and repentance must occur (2 Nephi 10:15, 4). These, of course, were two themes shown previously in chapter nine to have heavenly ascent implications.

That the physical blessings were couched in spiritual terms can also be seen in Jacob’s usage of the term “great knowledge.” In 2 Nephi 10:20, he uses it to describe the physical gathering, but this phrase is used by Nephi in 2 Nephi 32:7 and 1 Nephi 1:1 to refer to sôd-type mysteries. Depending on one’s view of the direction of intertextuality between Nephi and Jacob’s works, it is possible that Jacob is aware of how his brother consistently uses this term and that Jacob is purposely coupling these two ideas (physical gathering and sôd experiences) with the phrase “great knowledge.”

As the listeners’ faith increases in the one, their faith increases in the other. Considering this, the content in 2 Nephi 10:22 could be referring to either notion: “For behold, the Lord God has led away from time to time from the house of Israel, according to his will and pleasure. And now behold, the Lord remembereth all them who have been broken off, wherefore he remembereth us also.” At first glance, this reads as if it was referring only to a physical land of inheritance. Note, though, that [Page 178]2 Nephi 10:23 begins with the word “therefore,” directly tying its content to that of the previous verse. However, verse twenty-three then goes on to describe content that sounds more like heavenly ascent themes than it does geographical gathering:

Therefore, cheer up your hearts, and remember that ye are free to act for yourselves — to choose the way of everlasting death or the way of eternal life. Wherefore, my beloved brethren, reconcile yourselves to the will of God, and not to the will of the devil and the flesh; and remember, after ye are reconciled unto God, that it is only in and through the grace of God that ye are saved. Wherefore, may God raise you from death by the power of the resurrection, and also from everlasting death by the power of the atonement, that ye may be received into the eternal kingdom of God, that ye may praise him through grace divine. Amen. (2 Nephi 10:23–25)

Motifs like spiritual paths, eternal life, and praising God sound like heavenly ascent concepts, but, if so, then what is the connection between them and the geographical gathering in the previous verse? The answer might lie with Jacob’s carefully crafted agenda. That agenda may be to assuage his listeners’ concerns about their exile while at the same time instructing them on a greater topic: their spiritual exile and their return to God’s face through heavenly ascent.

Nephi’s comments as a redactor in the next chapter (2 Nephi 11) might further inform this question. First, remember that Nephi not only asked Jacob to speak but also assigned a topic to his brother (2 Nephi 6:4). Second, notice that Nephi points out that he purposely included only a portion of Jacob’s sermon, meaning that, as carefully crafted as Jacob’s message was, it received more sculpting by Nephi (2 Nephi 11:1). Third, pay attention to Nephi’s explanation as to why he chose to add Jacob’s words (and those of Isaiah) into his book. Nephi explained he did this “for” or because “[they] verily saw my Redeemer, even as I have seen him” (2 Nephi 11:2–3). In other words, the reason why Nephi assigned Jacob to speak on those specific chapters of Isaiah was because of Isaiah’s experience of literally seeing the face of God, which is one of the major themes in those chapters. Furthermore, what qualified Jacob to speak about the words of these chapters was that he (like Nephi and Isaiah) had literally entered the presence of God, as well.

Why is this important? It is because Nephi’s writings, as argued previously, are designed to explain his own heavenly ascent experience [Page 179]and to invite others to have their own.165 Therefore, it makes sense that if Nephi were to add other peoples’ writings to his book, he would choose witnesses who had had a similar heavenly ascent agenda as his. Understanding this, it is clear why Nephi chose Jacob and Isaiah as co-contributors to his book because they were witnesses of the validity and possibility of Nephi’s heavenly ascent invitation.166 Thus, Nephi was attempting to use Jacob’s and Isaiah’s additional witnesses “to prove unto them [i.e., the readers] that my words are true” (2 Nephi 11:3). This reasoning strongly suggests the principles that governed how Nephi selected Jacob’s topic and then redacted his sermon included the desire to create content that was primarily heavenly ascent centric.167

Therefore, assuming this is a correct interpretation of Nephi’s commentary in 2 Nephi 11, the content in 2 Nephi 9–10 is specifically designed to help readers understand and undertake a heavenly ascent [Page 180]experience. Reading this knowledge back onto the text greatly supports the analysis in this paper regarding the intent and content of those verses. For example, knowing that Nephi chose certain selections of Jacob’s words to add another testimony of ascending to God’s literal presence, Jacob’s phrase “true knowledge of their Redeemer” (2 Nephi 10:2) has clear heavenly ascent undertones. Likewise, as argued for previously, Jacob’s use of “perfect knowledge” while being judged in the presence of God has similar undertones (2 Nephi 9:13–14).

Considering all of this, the question might arise about how much influence Nephi had in the text of 2 Nephi 9–10 as it stands today. While including portions of Jacob’s sermon in his book, did Nephi add any of his own thoughts (as Mormon does through his redaction)? Would this explain some of the strong intertextualities between 2 Nephi 9 and Nephi’s sermon in 2 Nephi 31–32? How much discussion did Nephi and Jacob have about Jacob’s two-day sermon before he delivered it, or for that matter, how much discussion did Nephi have with Jacob about his redaction of Jacob’s content for his book in 2 Nephi? Though some of these questions might not be answerable today, it seems clear that the text as it has come down to us has purposeful heavenly ascent motifs dispersed throughout its pages.

In Relation to the Plan of Salvation

Considering 2 Nephi 9–10 compositely, it is clear the sermon contains many phrases and concepts that may reflect heavenly ascent motifs. These heavenly ascent motifs are less likely a series of coincidences and more likely the product of a careful and purposeful design on the part of Jacob and his brother, Nephi. Not only did Nephi assign the content for Jacob’s speech, he also then edited that speech with the overt purpose of proving his book’s agenda, which was arguably determined by his divine council experience. Therefore, the heavenly ascent motifs in Jacob’s sermon were most likely a part of a conscious design that was selected by both the speaker and his brother, who edited his words.

Considering the likelihood of this design in connection with the purpose of Jacob’s sermon, the thesis of this paper can now be directly addressed. First, notice that an overarching theme of this sermon is the “plan of the great Creator” (2 Nephi 9:6). In fact, referring to the sermon’s main problem and solution, Jacob exclaims, “O how great plan of our God” (2 Nephi 9:13). From this phrase and the overall context of this verse, it can be gathered that the purpose of Jacob’s sermon is to teach his listeners about God’s plan to “save all men” (2 Nephi 9:21), or, in other [Page 181]words, the plan that ends with mankind being “saved in the kingdom of God” (2 Nephi 9:23). This plan is the plan of salvation that this paper is attempting to address and is also the overarching theme of Jacob’s sermon. Even 2 Nephi 10, which arguably is more focused on geographical salvation than eternal salvation, still contains a similar message of God’s plan to save mankind, an idea described as being “received into the eternal kingdom of God, that ye may praise him through grace divine” (2 Nephi 10:24–25). Likewise, when Nephi describes the covenantal content of Jacob’s sermon, he refers to the material as “the great and eternal plan of deliverance from death” (2 Nephi 11:5).

With the understanding that this sermon is clearly teaching about the plan of salvation, consider the implications that this sermon is simultaneously packed with heavenly ascent motifs. When Jacob (or, for that matter, Nephi) refers to the plan of salvation, they do so in heavenly ascent terminology. Rather than beginning a description of the plan of salvation with the pre-earth life, these chapters start the discussion with the creation of the world. Unlike some popular models of the plan of salvation used today, which terminate in a description of several degrees of heaven, Jacob’s understanding of the plan of salvation simply culminates in a person being admitted to the presence of God, with no further description of a qualifying degree of glory.168 As the previous examination of the text demonstrates, the choice is not between levels of heaven but rather between ascension to God or descension towards the devil. Furthermore, instead of references to the spirit world, heavenly ascent motifs such as cleansing processes, secret knowledge, feasting on the word of God, prayer, and angels are found in this model between the creation of the world and an individual’s ascension into the Lord’s presence. This evidence seems to be a strong indicator that Book of Mormon prophets (at least Jacob and Nephi) viewed the plan of salvation within a heavenly ascent model. In other words, whether the ascension occurs in mortality (2 Nephi 11:2–3) or after death at the Final Judgment (2 Nephi 28:23), salvation in the Book of Mormon should likely be interpreted as redemption from the fall by entering back into the presence of God.

In addition to the above conclusion, these results also suggest the profitability of continuing this research with the other occurrences of the word “plan” in the Book of Mormon. Since 2 Nephi 9–10 supports [Page 182]this thesis, it is plausible that further research into other sermons about the plan of salvation may also support the thesis of this paper. As additional sermons are shown to have similar conclusions to those regarding 2 Nephi 9–10, and as additional authors are shown to view the plan of salvation in similar terms as to Jacob and Nephi, the hypothesis that Book of Mormon prophets viewed the plan of salvation in terms of a heavenly ascent paradigm will be further confirmed.

In summary, there exists a strong argument that Jacob’s sermon in 2 Nephi 9–10 is filled with heavenly ascent motifs that reflect Nephi’s use of heavenly ascent themes as well as the patterns in biblical and extrabiblical heavenly ascent writings. At the same time, one of the overarching themes of Jacob’s sermon is God’s plan of salvation for mankind. Considering these two conclusions together offers evidence that strongly indicates that Jacob viewed the plan of salvation in terms of a heavenly ascent model. Further research utilizing the hermeneutical approach used in this paper with other sermons in the Book of Mormon that are about the plan of salvation could continue to solidify this conclusion.

Go here to see the one thought on ““Heavenly Ascent in Jacob’s Writings in Second Nephi: Addressing the Question of What the Plan of Salvation is in the Book of Mormon”” or to comment on it.