[Page 161]Review of Jana Riess, The Next Mormons: How Millennials Are Changing the LDS Church (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019). 312 pages. $29.95.

Abstract: Riess’s book surveying the beliefs and behaviors of younger members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was supposed to compare the attitudes of younger generations with those of older generations. Unfortunately, flaws in the design, execution, and analysis of the survey prevent it from being what it was supposed to be. Instead the book is Riess’s musings on how she would like the Church to change, supported by cherry-picked interviews and an occasional result from the survey. The book demonstrates confusion about basic sampling methods, a failure to understand the relevant literature pertaining to the sociology of religion, and potential breaches of professional ethics. Neither the survey results nor the interpretations can be used uncritically.

Oxford University Press has a number of excellent titles in sociology and the sociology of religion that I can recommend.1 Unfortunately, [Page 162]the volume under review is not one of those. On the bright side, this book did not come out of the division of Oxford University Press that deals with sociology but out of the division that deals with religious studies. The unfortunate flip side is that this book did not benefit from peer review by someone who actually does social science.

The author of the book, Jana Riess, is a journalist with a PhD in American religious history from Columbia University, where she studied under Richard Bushman. She has no training in social science or statistical analysis and outsourced the statistical work on her book to others. Her book is based on a survey she calls “The Next Mormons Survey.” She put more effort into this book than typically expected from a journalist, and it shows, but the result does not attain the level of top-quality social science work. Riess’s book is not horrible, but it is plagued with problems. As David Frankfurter, professor of religion at Boston University, once noted, “[M]any scholars in Religious Studies have had a certain aversion to the positivistic use of evidence, borne of post-modern critiques of scientific verifiability and a general relativism toward truth-claims.”2 They thus tend not to be well situated to evaluate or use evidence, which shows in the book under consideration. On a certain level, the book deserves to be taken seriously, seriously enough to go to the effort to dissect certain aspects and analyze them carefully. I will discuss the problems with the book in order of the steps taken to put the book together.

[Page 163]Funding

We begin our examination of the problems with the funding of the Next Mormons Survey. Rather than get funding through an established academic funder who might question whether the author had the academic skills necessary to conduct the research, or might ask for better quality control on the survey, or required the raw data to be posted, Riess opted to use crowd sourcing. She obtained $19,665 from 245 donors with an additional $6,000 coming in later (p. 237). To provide incentives to donate, Riess provided rewards for different levels of contributions.3 For at least $15, one could get one’s name listed in the acknowledgements. For at least $60, one could also get a signed copy of the book. For at least $100, one could additionally get an executive summary of the research. For at least $500, the author would also make an appearance in the donor’s city.

At the end of the book (pp. 251–52) is a list of the individuals who funded the project at various levels.4 This is not uncommon with crowd funded books; it allows us to do a cursory analysis of the donor base. Fourteen individuals donated at least $500. Another 68 individuals donated at least $100. Donating at least $60 were 74 individuals, while another 60 donated at least $15 dollars. This means that 29 individuals donated less than $15. Not considering this last group and assuming only minimum donations, $19,140 are accounted for. Those in the under-$15 group cannot account for most of the difference, which would average $18 per person — enough to move them into a higher-donor category. This means that some individuals donated more than the threshold minimums, but most of them seem to have donated the minimum.

The list of donors raises some questions about conflict of interest and “pay to play.” At least four of the donors at the highest level are noted for being publicly critical of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and its stance on homosexuality, which features prominently in Riess’s survey and book. Are they funding Riess’s work because they agree with her, or are they influencing her? The participation of other funders also raises concerns. Armand Mauss helped fund the study at the highest level (p. 251) and also contributed to it (p. 249), helped write the questions (p. 249), and provided feedback on drafts of chapters (p. 250); his work is highly praised in the conclusions (pp. 234–35). David Campbell also funded the study at the highest level (p. 251), assisted with the study [Page 164](p. 249), commented on drafts of chapters (p. 250), and wrote a blurb for the book’s dust jacket, calling it a “tour de force.” Bill and David Turnbull helped fund the study at the highest level through their Faith Matters Foundation (pp. 250, 251) — where Riess sits on the board of directors (p. 251)5 — and helped write the survey (p. 249). Though Joanna Brooks is not listed as contributing money, she helped write the survey (p. 249), commented on drafts of chapters (p. 250), and wrote a blurb for the dust jacket praising its “top-notch social science research methods” and lauding it as “among the most important books ever produced in the field of American religious studies.”

It is fair to note that any or all of these individuals might be completely ethical and appropriate in their contributions, but the fact is that more than one had both financial and intellectual influence on the book, and in some cases, the book advocates for their political positions. Since the funding came in before the survey was done, it gives the appearance that those who funded the survey influenced the content and analysis of the survey. Or perhaps they had reason to be confident that Riess’s as-yet- ungathered results would be supportive of their political and ideological goals. It may be innocent, but the optics look bad.

Sampling Issues

Once funding was secure, the next step was to assemble the data. In total, “1,156 self-identified Mormons were included in the final sample, as well as 540 former Mormons, for a total of 1,696 completed surveys” (p. 238). The online survey was conducted between 8 September 2016 and 1 November 2017 (p. 238). Given the nature of the internet survey, the question remains open whether it was possible for individuals to take the survey multiple times, thus over-representing their opinions in the survey. Unfortunately, even if we disregard the possibility that individuals may have taken the survey more than once, the sample itself was not representative. The sample was assembled by chain referral sampling, which is not representative. Chain referral sampling (also called snowball [Page 165]sampling or network sampling) is a method of trying to learn about an uncommon group of people by getting those involved in the survey to refer others to take the survey. Although it “is generally regarded as a highly effective sampling technique that enables the study of populations who are difficult to reach or ‘hidden,’”6 it can fail in a number of ways, and the results are not representative. In the Next Mormons Survey, the object was to try to turn the sample into quota sampling by selecting surveys that fit various criteria, but Riess was unable to meet the quotas and so both altered the quotas during the survey and weighted the samples she had (p. 240–42). Quota sampling is frequently used in political science. The idea behind quota sampling is that the population sampled is divided into various demographic factors and that a certain quota of each demographic group is surveyed. Even if she had met her quotas, quota sampling is not representative sampling, and comparative studies consistently show that quota sampling generates poorer quality data.7

Riess herself is confused about various sampling methods. She discounts one survey because “it was obtained from a convenience sample (also called a ‘snowball sample’)” (p. 260 n. 36). Convenience samples are not the same thing as snowball samples. The classic example of a convenience sample is the psychology professor who does a study of the students enrolled in his psychology class.

Another potential for distortion in a chain referral sample is the influence of peer effects. By their nature, peer effects spread along the same networks that the referral process would use. Ironically, Riess unknowingly critiqued her own sampling method. As she says, “[I]t has some disadvantages that don’t pertain to a nationally representative sample, such as the reinforcement of the socioeconomic, religious, and/or educational biases that may exist in a person’s social networks” (p. 260 n. 36). We can say amen to that and at the same time wonder why she did not observe her own caution.

[Page 166]To understand why this is so, consider the following scenario: A researcher wants to find out general opinions and starts her sample with her friends. How many friends does she have? Although the basis for the Dunbar numbers is flawed,8 they are convenient numbers that seem to have some validity.9 Accordingly, people have on average 15 close friends of whom five are very close friends.10 Let’s say that the researcher sends out surveys to her 15 close friends and asks them to do the same. It was shown long ago that friends tend to have similarity of opinion, especially with regard to religion.11 Let’s assume that, on average, very close friends share 90% of their religious opinions and that close friends hold 80% of opinions in common. If all one’s close friends share the survey with 14 close friends, and then they share it with 14 friends, then 3,375 people will have taken the survey, and 57% of the opinions will still be shared with the original researcher. Even if very close friends share 85% of opinions and close friends share only 75% of opinions, almost half of the opinions in the final survey will reflect the opinions of the researcher.

While Riess claims to have “excellent reason to be confident that the NMS data is comprehensive and reliable” (p. 8), she actually gives reasons why her data are not reliable. (Some of these will be discussed below under social desirability bias.) An example of distortion in her sample shows up when she discusses the sexual practices of current and former members of the Church before their marriage. Out of her sample of 1,156 self-identified current members of the Church, 639 (55%) are married to their first spouse, and 211 (18%) have never been married (p. 84). This leaves 306 (26%) individuals who are (given the survey questions asked): cohabiting (5% ≈ 58), widowed (3% ≈ 35), separated or divorced (8% ≈ 92), or remarried (10% ≈ 116) (p. 75). A comparison with other surveys that are actually representative (p. 75) shows that she has about twice as many cohabiting Latter-day Saints as expected, half as many widows, and more than the average number of singles. This should have alerted her that her sample was obviously not representative.

[Page 167]Since Riess’s sample was not representative, her statistics may or may not be indicative of reality. We may never know. We can only determine that by carefully comparing them with more representative samples. What a shame that she wasted her opportunity to do things right.

The Qualitative Aspects

If the quantitative survey sample has problems, the qualitative aspects of the survey also have problems. The individuals sampled for the interviews do not come from the same population as those who provided the answers to the survey questions. Instead, these 63 interviewees were friends of friends (pp. 246–47). Unusual for this sort of book, “the majority of interviewees quoted in the book are identified by their actual first names” (p. 248), and one of the interviewees is cited by actual full name (p. 274n1). Riess also gives a number of identifying features about these individuals, although the details are sometimes inconsistent: one interviewee was variously listed as being 24 (p. 268 n. 18) and 25 (p. 280 n. 37) at the time of the interview. In the ethics of sociological research, researchers are supposed to do their utmost to keep the identities of participants confidential, so Riess at least gives the appearance of a violation of the ethics of the discipline.12 Such ethical rules do not exist just to protect the privacy of individuals, which they might well waive. Confidentiality also prevents virtue signaling and social desirability bias on the part of the research participants, and thus avoids an over-representation of those with a political axe to grind.

Riess uses material from all 63 interviews.13 These included 39 women and 24 men, about a three to two ratio. (Ironically, she complains that in her survey “more women were responding than men” [p. 241]). The bulk of the book is actually Riess’s commentary interspersed with these interviews, with the statistics brought in when they support Riess’s thesis. Riess has selected material from the interviews to tell the story she wants to tell.

Since Riess spends more of her time on her qualitative survey rather than her quantitative survey, it is worthwhile to look at the basic statistics for this survey. The age range of the women is 19 to 47 with a mean of 32 (σ = 5.94). The age range of the men is 21 to 44 with a mean of 31 (σ = 6.49). What is really interesting is the mode, which is 25 for the men and 37 for the women. All of the interviewees were from what Riess considers [Page 168]Generation-X (m=4, f=9) or Millennials (m=18, f=29). This is somewhat odd for a survey supposed to compare the views of various generations.

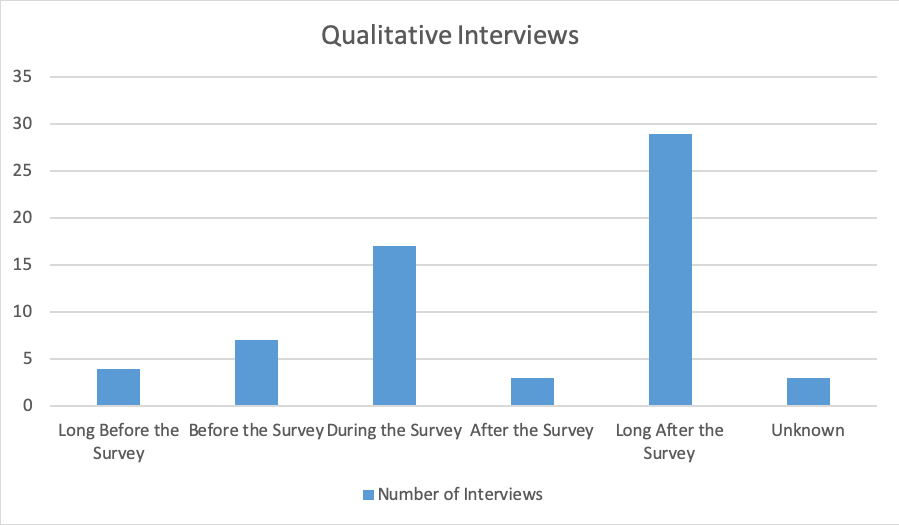

We can divide the interviews into five periods: long before the survey (2012–2014) (four interviews), before the survey (22 June–7 September 2016) (seven interviews), during the survey (2 November 2016–12 November 2017) (17 interviews), after the survey (7 February 2017–5 May 2017) (three interviews), more than six months after the survey (2 June 2017–4 November 2017) (29 interviews), and unreported (three interviews); see the following chart. The bulk of the interviews came after the survey during the writing of the book and appear to have been solicited to make the points that Riess wanted to make.

Since excerpts from all the interviews were inserted into the story but come from multiple periods, the question arises whether Riess was simply conscientious in inserting something from all the interviews into the book, or if Riess is only counting those interviews she did use. The timing of the interviews suggests the latter. Almost half the interviews were done more than six months after the study and mostly after the study results were analyzed. This suggests that the results of data did not sufficiently tell the story Riess desired and that the interviews were carefully selected to provide the requisite narrative. What are the chances that a representative sample of 63 Latter-day Saints would contain not just one but two Latter-day Saints who claimed to be transsexual? It [Page 169]cannot be coincidence that Riess’s interviews with those claiming to be transsexual both occurred on the same day.

Our hypothesis in this analysis is that the interviews long before the survey come from interviews Riess happened to record and insert into the study. The interviews that come before the survey will be reflected in the wording of the survey. The interviews that come during the survey will reflect more normal points of view of Church members and tend to be more orthodox. The interviews after the survey will tend to reflect Riess’s point of view. The clearest example of Riess’s soliciting interviews to support a preconceived thesis is in her chapter on race (pp. 109–28). The interview conducted during the time when Riess was conducting her survey depict race relations in the Church in a positive light. The individual claimed that “being a racial minority has been more of a problem with non-Mormons than it has been within the church” (p. 113). Riess, however, gives the appearance of having wanted to depict the Church as racist and slow to change and so uses interviews from after the survey (and one from before) to depict the Church in a negative light. This looks both intentional and like evidence of bad faith.

Biased Questions

The questions themselves are available14 and provide some interesting insight into what those compiling the survey were interested in but also rather revealingly into some of their blind spots.

For an example of the biases in the survey questions, consider the issue of authority. To members of the Church of Jesus Christ, the priesthood represents the power, authority, and responsibility to act in the name of God, to say and do the things that Jesus would say and do if he were here, and have those acts ratified by heaven. To those who composed the survey, the priesthood comprises the following things: “Sunday priesthood meetings, Home teaching, Priesthood social activities, Priesthood service opportunities, Priesthood curriculum and church lessons,” that certain males were not given it before 1978, and that women are not given it (the last two appeared four times each in the survey). In Latter-day Saint thought, priesthood is intimately connected with covenants and ordinances. To make a covenant with God that God will actually recognize, God or his duly designated representative has to be a participant. Thus, Latter-day Saints believe that someone [Page 170]“must be called of God, by prophecy, and by the laying on of hands by those who are in authority, to preach the Gospel and administer in the ordinances thereof” (Articles of Faith 1:5). If one thinks that God has a role in authorizing and appointing those who represent him, then if one has a problem with that, one takes it up with God. If one thinks that the priesthood is merely a social club that dictates who gets to attend which parties and meetings, then who is allowed into the mortal social club becomes a political issue, which is the way that Riess portrays it. In baptismal interviews and temple recommend interviews, questions about the priesthood all center on whether the individual believes and accepts that the priesthood is the authority of God and that it is properly held and transmitted. The survey contains no questions about that. Now I can understand researchers being interested in what they are interested in and asking questions accordingly, but if one’s thesis is that younger members of the Church do not accept the basic doctrines, shouldn’t one at least ask about the basic doctrines?

The survey contains nothing about faith in Jesus Christ, covenants, or repentance. Ordinances are only mentioned once. The only blessings mentioned in the survey are the blessing of infants. The sacrament is mentioned only in the context of changes to sacrament meeting. The proposed list of changes is an interesting study into what the authors of the Next Mormons Survey (which included more than just Riess) think would make sacrament meeting better: shorter, with more music played on different instruments, without children, but with guest speakers from the local community and PowerPoint presentations. Interestingly, almost none of these ideas were actually popular (p. 157), which shows that the authors of the survey do not exactly have their fingers on the pulse of their objects of study.

Interestingly, Riess repeatedly notes important issues she forgot to ask about as she was preparing her survey (pp. 44, 59, 84, 154, 199, 206). Thus, she admits her survey questions were not thought through very well in spite of all the advice she got on them.

Social Desirability Bias

Social desirability bias is the phenomenon in which individuals give the answers on surveys they think are socially desirable rather than accurate. How do we know the answers given in the survey conform to what individuals thought those administering the survey wanted to hear, or projected an image of participants who matched what they wished were the case rather than what was actually the case?

[Page 171]There is already a literature on social desirability bias among Latter- day Saints. Researchers have found an “inverse association between Mormons and socially desirable response bias.”15 So Latter- day Saints are more likely to be honest on surveys than other religious groups. My concern is not so much about Latter-day Saints being honest, but whether those on the margins of the faith or who have left the faith are being honest, because other studies dealing with social desirability bias have shown that “less religious people” are more likely to report their behavior inaccurately.16

This is not an abstract problem. Riess herself reports on an interview with a woman “who is not a believer but holds a temple recommend” (p. 31) and “has stopped wearing garments” (p. 67). Though the interviewee admits to violating at least two of the conditions for a temple recommend, she still has one. She is quoted as claiming, “I will go in and just say whatever I need to say” even though that “can seem dishonest” (p. 67). Seem? This woman who participated in Riess’s project wore (and perhaps still wears) a mask of social desirability at least to her Church leaders if not to her congregation and perhaps even to her family. This is not the only example of this that Riess reports. Riess tells about another individual who renewed a temple recommend despite not sustaining Church leaders even though she “felt very disingenuous” (p. 222). Riess reports approvingly on a member of a group of students at BYU who would lie for each other to the “draconian” Honor Code Office at BYU about their sexual activities because it was “empowering” and a reason to be “proud” (p. 141) and of another group that conspires to keep their violations of the Word of Wisdom secret (p. 162). This actually documented behavior puts the validity of the responses of those who are on the margins of the Church or have left the Church into question. Are they just saying what they feel they need to say in order to project a particular image while considering themselves faithful “in my own way” (p. 157)? Does the fact that they are being identified by their true name(s) mean that they have an image among the disaffected to protect or enhance?

How bad is the problem in this survey? Riess has a whole section documenting the extensive social desirable bias in her survey (pp. 155– 56), [Page 172]including that “43 percent of the ‘very active’ Millennials [in her survey] had not been to church” within the last month (p. 156). Should we assume that almost half of the respondents are providing incorrect information? Alternatively, we could say that 44% of the survey respondents were Millennials (p. 243); 79% of those said they were very active (p. 155), and 43% of those were dishonest about that (p. 156). That means at least 15% of Riess’s total sample gave socially desirable rather than honest answers. Either way, this information reveals a statistically significant problem with the data and completely undercuts Riess’s assertions about the reliability of the data. While Riess claims “the results we report in this book are representative of the wider Mormon and former Mormon populations in the United States within the standard margins of error (±3 percent and ±4 percent, respectively)” (p. 244), this should be revised to a minimum of ±15% — and this without even considering the issue of biased sampling from the outset.

Interpretation

Riess says she began her survey because other national representative samples showed that “Mormon youth were more likely to hold religious beliefs similar to their parents’, share their faith with others, pray regularly, and discuss religion in their families” (p. 3). Riess, however, believes “the number of young adults who are leaving Mormonism appears to be rising sharply” (p. 4). She believes “the church’s conservatism on social issues has become an obstacle” (p. 4), and she would like to change that. Riess began with her conclusions and then searched for evidence to support those conclusions. Riess’s starting conclusions are that the Church is losing young people in droves because of the Church’s stance on homosexual relations and gender issues. The best she can do, however, is note that 23% of those who left the Church did so for those reasons (p. 224). The number one reason those individuals gave was that they could no longer reconcile their lifestyle with the teachings of the Church.

Fortunately, Riess’s study came out at the same time as two other studies on the same subject. One, by the Gallup organization, using longitudinal information, pointed out that while membership in religious organizations has in general been declining, “membership in a place of worship has been stable among Mormons (near 90% in both time periods) and Jews (in the mid- to low 50% range in both time periods) over the past two decades.”17 So according to Gallup, membership in the Church [Page 173]of Jesus Christ in the United States has been holding steady for the past two decades. The Church, at least in the United States, is not losing people in droves, notwithstanding Riess’s anecdotal conclusion. The other study — using data from the same Pew Religious Landscape Survey that Riess claimed showed “a quietly rising tide of disaffiliation from the LDS Church in the United States” (p. 4) but this time analyzed by someone with training in using data — concluded that “the most warranted conclusion is that the Church is in a state of stasis in terms of religious switching.”18

The conclusions of others with more training and experience working with statistical data provides a useful check on some of Riess’s interpretations. For example, Riess goes to great lengths to emphasize that the Church’s treatment of women is “a relic from another age” (p. 58). Yet, we need to consider that in the Pew Religious Landscapes survey, “men are overrepresented among those who have left; these results comport with prior findings in the large American Religious Identification Survey that men tend to disproportionately leave the Church.”19 It is difficult to argue that gender issues are driving an exodus from the Church, since it is predominantly men rather than women who leave.

Also, if the Church is not politically liberal enough in Riess’s view, and that were causing members to leave, one would expect that those leaving would be joining liberal Christian churches, but relatively few do.20 This would indicate that leaving for political reasons is less likely than other factors.

Riess claims the younger generation of members of the Church are declining in faith. It apparently never occurred to her that it might be a stage-of-life issue rather than a generational issue (p. 255 n. 9); a dip in religious observance among some portion of unmarried individuals in their late teens and early twenties is a well-known phenomenon that has been occurring for at least the last half a century and has been discussed in the literature.21 The longitudinal National Studies of Youth and [Page 174]Religion found that Latter-day Saint Millennials became more faithful over time, not less. Thus, weekly Church attendance went from 84% of Latter-day Saint teenagers to 93% as young adults. As teenagers, 63% of Latter-day Saint Millennials prayed daily, but as young adults, 89% did. As teenagers, 26% of Latter-day Saint Millennials read their scriptures daily, but as young adults, 44% did.22

Riess finds the fact that “former Mormons are about twice as likely to have engaged in forbidden practices like sexual intercourse outside of marriage” to be “startling” (pp. 83–84). Considering that a loss of faith correlating with increased sexual activity outside of marriage — not just in Latter-day Saints but in other religions as well — is well documented,23 there is no reason for it to be startling. Riess does not give enough statistical information to answer the question if we ask it this way: If one engages in forbidden practices outside of marriage, is one more likely to remain a member or leave the Church? Since her sampling method was flawed, could we trust the answer even if she had provided the data? A better designed and executed survey could probably have provided answers.

If Riess had actually read more of the relevant literature, she might have avoided these sorts of mistakes in her interpretation of the data.

[Page 175]Riess and the Prophets

Riess has chosen not to use the full name of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or follow the Church’s style guide in referring to the Church or its members. Her explanation of this is revealing: “the terms ‘Mormon’ and ‘Mormonism’ are legitimate scholarly labels to refer to the religious branches that stem from Joseph Smith’s Latter-day Saint movement, including The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and its members.”24 Apparently for Riess, scholars trump prophets.

Riess’s treatment of the leaders of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints would appear to give a good idea of her opinion of them. She cites them primarily to criticize them. Thus two members of the First Presidency, Russell M. Nelson and Dallin H. Oaks, are said to put members of the Church who disagree with the Church’s moral stances in “an uncomfortable situation” (p. 184), though one could argue that the individuals put themselves in that situation. Boyd K. Packer is criticized for his emphasis on families (p. 88), his teachings against certain pro-homosexual arguments (p. 135), and his statements about how the Church generally works (p. 202). Praise of prudence or foresight on the part of Latter-day Saint leaders is relegated to the footnotes (p. 281 n. 52; 285 n. 3). If a Church leader is acknowledged for being aware of a problem, the problem is “far more serious than he seemed to indicate” (p. 228). Such statements betray an arrogance on Riess’s part, since apostles are far more aware of what is going on among Latter-day Saints than she is. They have access to more, better, and more competently analyzed statistical data than Riess does. They routinely talk to far more Latter- day Saints than she does. As expressed by Elder Quentin L. Cook, “over a four-year period, every single stake and ward, district and branch, in the Church has a member of the Twelve [Apostles] coming and meeting with its leaders — and training them on prophetic priorities.”25 As Elder Gerrit W. Gong put it: “As we go different places, we feel the goodness of the members. … We hear the experiences and we learn things that help us to understand as we counsel together as a quorum about what is happening in the different parts of the world and in different groups within the Church.”26

[Page 176]An admission by Dieter F. Uchtdorf that sometimes leaders make mistakes is, for Riess, an illustration of “just how taboo it is to criticize or publicly disagree with an LDS prophet or apostle” (p. 191). If Riess actually believed that, she would not be doing it. This is merely a public posture that lets Riess feign some sort of intellectual courage when she knows it is not actually the case.

Some Small Details

A number of years ago, I made the observation that those involved in Mormon Studies could not necessarily be counted on to get details and even basics right.27 Riess provides a number of examples of that. For example, Seminary is not required to serve a mission (p. 25); the missionary application does not even ask about it. Riess claims that “Even the notion that Mormons would call the president of their church ‘the prophet’ is a mid-twentieth-century innovation; the practice can be dated to 1955, during the presidency of the exceptionally popular David O. McKay. Before 1955 the term ‘prophet’ was used in LDS periodicals to refer to founding leaders Joseph Smith and Brigham Young, or else prophets from scripture” (p. 191). This is an intriguing theory, but it does not work. The popular hymn “We Thank Thee O God for a Prophet” entered the hymnal in 1863.28 In 1883, Franklin D. Richards, an apostle, called John Taylor “our Prophet, who had been illegally imprisoned.”29 Evan Stephens wrote a hymn whose opening line is “We ever pray for thee, our prophet dear” for Wilford Woodruff’s 90th birthday in 1897.30 On 6 October 1899, Seymour Young referred to “our Prophet, Seer and Revelator, Lorenzo Snow.”31 The children’s song “Stand for the Right” was written by Joseph Ballantyne who died in 1944, before President McKay was the prophet. The line “Our prophet has some words for you, And these are the words: ‘Be true, be true.’” would seem to refer to Joseph F. Smith. These are just a few examples that show that Riess is wrong on this point.

[Page 177]Positive Signs

One of the positive things that can be said about Riess’s book is that even if it does not meet the standards one might have come to expect from high-quality social science, it is much better than we have come to expect from journalists.

One of the sad things about Riess’s missteps is that they undercut some interesting observations she does put forward. I will highlight only a few, but note that, unfortunately, the significant errors make it difficult to tell whether some of the observations are accurate or mirages.

Riess claims that “a majority of former Mormons, especially older ones, already had significant cracks in their testimony during adolescence” (p. 218). If true, this is an important observation.

Riess noted that the only proposal for changes in sacrament meeting that she put forward which had much popularity was shortening sacrament meeting (pp. 156–57). As her book was at press, sacrament meetings were shortened, though only by ten minutes. What this shows, however, is that in large measure Latter-day Saints do not feel the need to change the Church or the way it worships. For the most part, it meets their spiritual needs. Riess certainly could have made more of this observation had she reflected on it more and been less interested in pushing her own agenda.

When Riess asked former Latter-day Saints why they left the Church, “the only specific historical or doctrinal issue to rank among the top ten was concern about the historicity of the Book of Mormon and the Book of Abraham” (p. 233). Based on my own experience, this sounds correct. The historicity of ancient scriptural texts is probably the biggest intellectual reason that members of the Church leave the faith. The response, if one is interested in increasing faith, is to support the historicity of the scriptures, not capitulate on the issue. Capitulation on this issue simply causes more people to lose faith.

It is a shame that Riess’s methodological and interpretive failures as well as her ax-grinding will bring into question some of her more salient insights.

Conclusions

Riess ends every section of her book on a negative note. The introduction ends claiming that “young adult Mormons … struggle with whether they will be able to live all the commandments of a strict Mormon lifestyle” (p. 9). The first chapter ends telling about a woman who “sometimes felt overwhelmed by serious doubts” (p. 32). The second chapter tells the story of a young man leaving the Church after his mission (pp. 47–48). [Page 178]The third chapter claims that members who will not wear their temple garments are “the proverbial canaries in the coal mine, portending trouble for the future” (p. 68). The fourth chapter ends with “the case against singles wards” (pp. 87–89). The fifth chapter ends questioning whether the Church should stick with its traditional understanding of gender (p. 108). The sixth chapter ends with charges of “racism and sexism in the church” (p. 128). The seventh chapter claims that “tensions over LGBT issues have reached a new level of intensity,” and as a result people are “leaving the Church” (p. 146). The eighth chapter ends claiming that “Millennials are not tying their identities as ‘active’ Mormons as strictly to practices like attending church meetings or keeping the Word of Wisdom” (p. 168). The ninth chapter would have ended claiming that Latter-day Saints play “bishop roulette” (pp. 205–6), but Riess found that patriarchal blessings complicated her thesis. She ends the book with a chapter on those who leave the Church, claiming that “most young adults who leave Mormonism are unlikely to come back” (p. 231).

I have looked at quite a few statistical studies dealing with the loss of faith in general and the state of teenagers and adults in the Church in particular, and I think they paint a much brighter picture of the Church and its members than the one Jana Riess paints. True, it is not a picture of blue skies and endless sunshine as far as the eye can see. The breathtaking vista has its share of threatening storm clouds boding serious challenges, but the picture that emerges shows the majority of the Saints are striving to do what is right and succeeding in doing so. Even the statistics in Riess’s book show that we Saints are generally doing better on many fronts than we have in the past. Nevertheless, if the Church were to follow Riess’s recommendations, the Church probably would see a mass exodus.32

Because Riess’s sample was unrepresentative and because she often, by her own admission, did not ask the right questions and because her interpretation is negative, one should be careful about using her statistics or following her conclusions. There are better reasons for hope for the Church of Jesus Christ than what is presented in her book.

Go here to see the 20 thoughts on ““Conclusions in Search of Evidence”” or to comment on it.