[Page 295]Abstract: In light of Noel Reynolds’ hypothesis that some material in the Book of Moses may have been present on the brass plates that Nephi used, exploration of concepts related to chains in the Book of Moses led to several insights involving a group of related motifs in the Book of Mormon where shaking off Satan’s chains and rising from the dust are linked, as discussed in Parts 1 and 2. Here we argue that an appeal to the Book of Mormon’s use of dust may fill in some gaps in the complex chiastic structure of Alma 36 and strengthen the case that it is a carefully crafted example of ancient Semitic poetry.

In Part 1 we pursued an insight from Noel Reynolds regarding the possible relationship between the Book of Moses and the brass plates, leading to the discovery of a potential Hebrew wordplay and much richer meaning than previously realized in references to dust, chains, and obscurity/darkness in Lehi’s final speech. This led to exploration of the Book of Mormon’s subtle and profound use of ancient dust related themes, explored in Part 2, where we saw that the use of dust as a theme strengthens the Book of Mormon’s covenant-related message and highlights the role of the Redeemer while also serving to solidify the legitimacy of Nephite political power. By recognizing a complex of related themes and motifs in this aspect of the Book of Mormon, we [Page 296]can now approach some puzzling aspects of Alma 36, including alleged deficiencies. While some LDS scholars view Alma 36 as a masterpiece of Hebraic chiasmus, some writers deride it as too sloppy and loose to count as a deliberately composed chiasmus. Through consideration of its use of dust-related themes, a new case can be made that the questioned sections may actually be tightly interwoven, complex poetic strands with abundant evidence of poetic craftsmanship directed at delivering the core message of the Book of Mormon.

The Importance of Chiasmus

Chiasmus, a form of parallelism used as a poetical structure noted particularly in some ancient writings from the Middle East and Greece,1 has become well known to students of the Book of Mormon2 and students of the Bible.3 This flexible and powerful form of parallelism was not widely recognized as a hallmark of biblical poetry until just a few decades ago. Even the basic concept of poetical parallelism in the Hebrew Bible, though common knowledge today, was largely unrecognized until two centuries ago when it was elucidated, as Yehuda T. Radday observes with some irony,4 by a Gentile, Robert Lowth.5

[Page 297]Chiastic structure is not limited to poetry alone and can be an important element of biblical narrative, as Radday ably illustrates.6 The presence of chiasmus, especially detailed or lengthy chiastic structures, may be among the multiple factors that might temper some of the claims that scriptural texts, both in the Bible and the Book of Mormon, are “pious fiction” concocted centuries after the records claim to have been written.7 However, sometimes passages which are said to be chiastic may have received subjective and contrived interpretation that could discover false positives arising from chance repetition rather than the intent of an author. Welch has provided criteria for recognizing genuine, high quality chiasmus,8 and Boyd Edwards and W. Farrell Edwards have provided statistical tools for estimating likelihood that a chiasmus was intentional.9

While some Book of Mormon chiasms are dense and remarkably easy to map, Alma 36 is more complex but still ranks as extremely unlikely to be due to random chance according to Edwards and Edwards10 and meets rigorous criteria in Welch’s assessment that allows him to label it as a “masterpiece.”11

Dusting Off an Overlooked Portion of Alma 36

[Page 298]The chiastic nature of Alma 36 has been a popular topic for LDS students of the Book of Mormon and LDS apologists,12 but it is has been met with criticism. It is said to ignore too many words and be uneven or loose, with some pairings consisting of a few words selected from lengthy passages, and to ultimately be the result not of Alma2’s craftsmanship but of John Welch’s creativity imposed on the text.13 Such objections can be fairly raised. The beginning and end of the chiasmus are strong and compact, and the center point, where Alma2 turns to Christ, is also distinct and relatively compact. The portions in the middle sections between the center and the ends, though, are less clear or less concise, with some steps in the chiasmus spread out as a general concept covering multiple verses where critics can accuse LDS scholars of looking for patterns that aren’t there.

There is a reasonable general response to such objections: when relating history, there are things that need to be said that won’t fit nicely and compactly in a chiasmus. But at the pivot point, generally the most important part of the chiasmus, and at the end points, which are also often important, the chiasmus is relatively clear and strong in Alma 36. The middle ground is still chiastic, though apparently more diffuse.

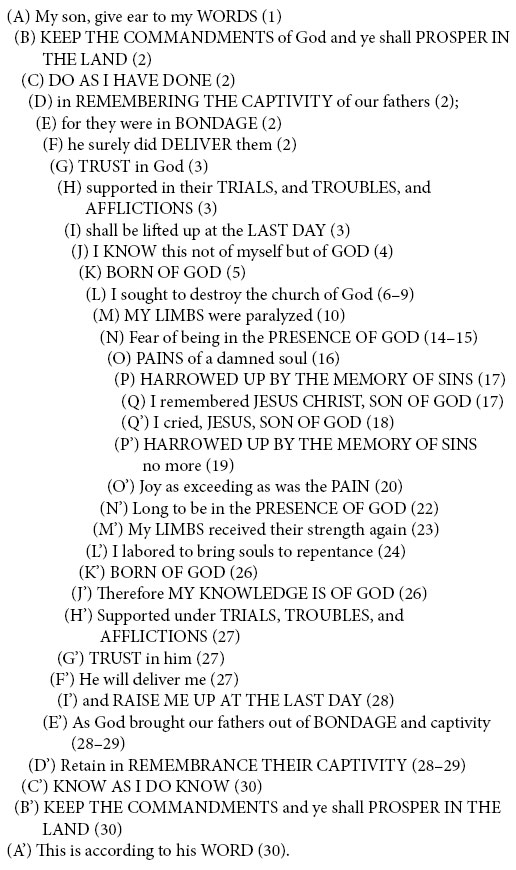

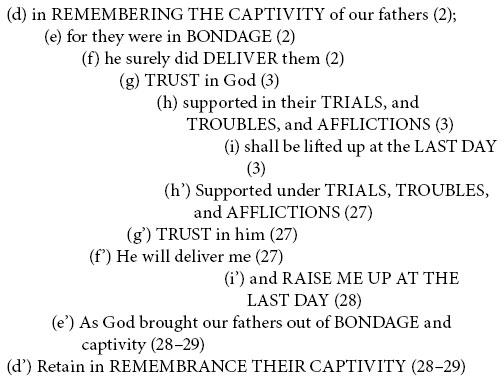

Here is a typical framing of Alma 36, taken from John Welch,14 showing the structure of key elements among the verses:[Page 299]

Some loose spots include item I’ in v. 28 apparently showing up a verse late (due to a slip or more of a necessity in the original language or [Page 300]a translation issue?) and big gaps or significant looseness around item L (the concept of destroying the church of God, vv. 6–9), item M (MY LIMBS paralyzed in v. 10) and item N (fear of being in the PRESENCE OF GOD, vv. 14–15).

Donald R. Parry in Poetic Parallelisms in the Book of Mormon offers a different but related structure with fewer steps (11 instead of Welch’s 17).15 The structure offered does not solve the problem of apparent looseness. Parry’s item H, for example, spans verses 6 to 11, while item I extends from verses 12 to 16, both with many words that don’t contribute to the chiasmus.

As a specific example the objections from Wunderli, the word rack occurs four times in Alma 36 but all in the first half of Welch’s chiasmus without being paired with rack in the second half. Wunderli notes that Welch uses only one of those instances, relabeling its presence in v. 14 as “fear of being in the presence of God” (actually, that is what rack is conveying in v. 14 as Alma2 expresses the horror he was racked with at the thought of coming into the presence of God). This relabeling is done to create a chiastic pairing with v. 22, where Alma2 longed to be in the presence of God.16

Wunderli makes a similar objection to the end points of the chiasmus. While Welch sees significance in the use of words or word at the beginning and end of the chapter, word occurs elsewhere in Alma 36 without being paired to other parts of the chiasmus, making the appearance of paired concepts at the beginning and end of the chapter seem to Wunderli to be the fruit of Welch’s creative selection of words rather than poetical intent.17

While some of his points are logical, Wunderli’s approach seems to assume that chiastic pairs must independently stand out with a unique pairing. This approach may be like objecting to a pair of rhymes in a proposed sonnet because other words elsewhere in the sonnet may also rhyme with the words in question. The issue is not whether there are other words that rhyme in the sonnet or other words similar to those of a chiastic pairing but whether a rhyme/pairing exists in the right place. Alma2’s use of words/word at the beginning and end of the chiasmus [Page 301]is readily recognized as being paired. The strength of the pairing and the appropriateness of the expressions they are in are not diminished by using a similar term in a different context elsewhere in the chiasmus, whether a key concept that is also paired or not.

As for Alma2’s five instances of racked within four verses of Alma 36, all in the first half of the chiasmus, this is an appropriate and graphic descriptor of the pain that is the subject of the first half, before the dramatic transition at the powerful and majestically appropriate pivot point. There is no reason to expect the same word to occur in both halves of the chiasmus and no legitimate reason to object to Welch’s labeling. But Wunderli does have a point about the word rack used prominently without being part of the chiasmus in four of its five instances.

Taking Wunderli’s objection to the use of rack as an invitation for further analysis, there appears to be something of a sub-pattern involved in the verses using rack:

12 But I was racked with eternal torment, for my soul was harrowed up to the greatest degree and racked with all my sins.

14 … the very thought of coming into the presence of my God did rack my soul with inexpressible horror … .

16 And now, for three days and for three nights was I racked, even with the pains of a damned soul.

17 And it came to pass that as I was thus racked with torment, while I was harrowed up by the memory of my many sins, behold, I remembered also to have heard my father prophesy unto the people concerning the coming of one Jesus Christ, a Son of God, to atone for the sins of the world.

The usage of racked as shown above suggests further parallelism, almost a mini-chiasmus within a chiasmus:[Page 302]

Racked / torment / harrowed / sins

Racked / soul (taking “did rack” as equivalent to

“racked”)

Racked / soul

Racked / torment / harrowed / sins

This rack-laden passage from Alma 36:12–17, dominating the Book of Mormon’s use of that verb, can effectively and fairly be summarized as Alma2’s expressing his fear and horror of coming into the presence of God, for his soul truly is harrowed by his sins. It collapses into item N in Welch’s formatting of Alma 36, but the structure within the structure suggests there may be something more than random redundancy in a sloppy mid-section of the chiasmus.

Back to Brueggemann

In Part 2, we discussed the ground-breaking work of Walter Brueggemann in showing the rich uses of dust-related themes in the Hebrew Bible.18 These themes can relate to covenant keeping, resurrection, receiving authority, enthronement, and exaltation. For covenant breakers, dust themes can involve a return to the dust, loss of authority, spiritual or physical death, and destruction.19 In the Book of Mormon, Isaiah 52:1–2 is especially important from that perspective, for the call to arise from the dust and shake off chains is an important theme for Nephi and others there. Related concepts reviewed in Part 2 include themes of trembling, shaking, falling, rising, and standing.

Alma 36:7–11, one of the apparent weak spots in the chiasmus, provides several dust-related terms and concepts:

7 earth did tremble beneath our feet … fell to the earth … fear of the Lord

8 … the voice said unto me, Arise. And I arose and stood up

9 … destroyed … seek no more to destroy the church of God

10 … I fell to the earth … three days and three nights …

11 … destroyed … destroy no more … fear … destroyed … fell to the earth and did hear no more

[Page 303]The earth trembles, the dust of the ground is shaking under Alma2’s feet, and he falls down — toward the dust — with talk of destruction and the implication of death (cf. Mosiah 27:28). There appears to be a deliberate relationship with dust themes.

Alma2 has broken the covenant and is at risk of losing his status and even his life. Surprised by an angel, amazed at God’s power and reality, he falls to the earth — to the dust. As Lehi commanded his sons, the angel commands Alma2 to “Arise.” Literally, he is to arise from the ground, from the dust. He stands but cannot remain standing in light of his sinful, unstable state. He faces destruction for the work of destruction that he has done. The flame of guilt ignited, he falls again to the earth — to the dust — and is as if dead for three days and three nights, a symbol of the grave in Hosea 6:2 whose analysis in terms of covenant-making by Wijngaards20 provided an important foundation for Brueggemann’s work. This is also an apparent reference to the prophesied time that Christ would spend in the grave (see Nephi’s prophecy in 2 Nephi 25:13, and the related prophecy of Zenos on the brass plates, mentioned in 1 Nephi 19:10).

Once again we are told that faced with destruction, in fear and amazement, he fell to the earth and could hear no more.

On the other side of the pivot point, where item M’ refers to limbs receiving strength in v. 23, there may be even more parallels in this chiasmus:

22 Yea, methought I saw, even as our father Lehi saw, God sitting upon his throne, surrounded with numberless concourses of angels, in the attitude of singing and praising their God; yea, and my soul did long to be there.

23 But behold, my limbs did receive their strength again, and I stood upon my feet, and did manifest unto the people that I had been born of God.

24 Yea, and from that time even until now, I have labored without ceasing, that I might bring souls unto repentance; that I might bring them to taste of the exceeding joy of which I did taste; that they might also be born of God, and be filled with the Holy Ghost.

[Page 304]25 Yea, and now behold, O my son, the Lord doth give me exceedingly great joy in the fruit of my labors;

26 For because of the word which he has imparted unto me, behold, many have been born of God, and have tasted as I have tasted, and have seen eye to eye as I have seen; therefore they do know of these things of which I have spoken, as I do know; and the knowledge which I have is of God. [emphasis added]

In light of Brueggemann’s work, falling to the earth in Alma 36 may do much more than just convey Alma2’s great fear, but may serve as an equivalent to returning to the dust, invoking these symbols:

- physical death

- spiritual death (falling away from God)

- rebellion, sin, breaking the covenant

- losing power, authority, life

- destruction

The association of death with falling to the earth is reinforced with many elements, including references to destruction, the deathlike state of his body, suffering the pains of hell, and Alma2’s being in this state “for three days and three nights” (v. 10).

The possibility that Alma2’s fall to the earth is meant to be associated with the dust-related themes introduced by Lehi is reinforced by the words, or rather word, of the angel to fallen Alma2: “Arise” (v. 8). This word is repeated as Alma2 states that “I arose and stood up,” unnecessarily redundant unless Alma were reinforcing the word arise.21 Alma2 explicitly mentions Lehi in Alma 36:22, the prophet who used Isaiah’s dust-related imagery so effectively in his final speech to his sons.

In considering the terms that could stand in contrast to such a fall to the dust of the earth, literally a case of “falling again,” what could be more appropriate than being “born again,” with its implications of spiritual renewal, entering into the covenant, and receiving life, power, and grace from God? Just as our “loose” upper midsection of the chiasmus mentions Alma2’s fall to the earth three times, the related section in the lower midsection also mentions being born again three times.

In light of the dust/death/fall themes in the upper midsection and the contrasting concepts of being born again and entering into the [Page 305]covenant with God in the lower midsection, perhaps the seemingly sparse, amorphous mid-sections of the chiasmus’s wings are actually loaded with more structure than previously realized.

The loose section, comprising vv. 5–15 on the upper side and vv. 23–26 on the lower, spanning items K, L, M, and N in Welch’s mapping, actually has more than just 4 little phrases in common. There are multiple concepts with multiple dimensions interspersed in a complex passage. Rather than neatly parse it as a simple linear chiasmus, look at the interwoven block of themes.

The first section has these major themes:

- Alma2 falls to the earth. After being told to “arise,” he arose and stood up but soon fell again. He is literally “fallen again” in the presence of an angel, fallen from God. His falling to the earth is mentioned three times (vv. 7, 10, 11).

- Alma2 is like one who is dead. He can’t move his limbs (v. 10), he can’t open his mouth (v. 10), and he can’t hear (v. 11). Three times we learn that his body isn’t working: limbs, mouth, and ears are not functioning.

- He is not only as if dead but as if in hell, experiencing the pains of a damned soul (vv. 12–13). Body and soul are affected.

- Alma2 was seeking to destroy the Church of God. This is mentioned three times (vv. 6, 9, 11). Speaking of destruction, he is warned that he will be destroyed if he keeps seeking to destroy the Church of God.

- He has not kept God’s commandments, meaning that he has departed/fallen from the covenant (v. 13). Worse yet, he has led others away from God, causing them also to die, or he “had murdered many of his children” (v. 14), causing inexpressible horror at the thought of coming into God’s presence.

- He yearns to “become extinct [dead] both soul and body” (v. 15).

- These events are precipitated by the appearance of an angel (v. 6), who speaks to the sons of Mosiah with the voice of thunder (v. 7).

Now compare that section from vv. 6–14 with the related loose section on the other side of the pivot point, vv. 23–26, which has these major themes:

- Alma2 returns to life (physically) and is born again (spiritually), in contrast to being “extinct both soul and body” and in contrast to his deathlike state before.

- [Page 306]Being “born of God” is mentioned three times (vv. 23, 24, 26) in this section.

- He regains the use of his limbs (v. 23) including his feet. His mouth functions for he “manifests” his change to the people (v. 23) and helps others to taste as he tastes (v. 24). His eyes function for he helps others to “see as I have seen” (v. 26). This is in contrast to the three ways his body wasn’t working properly before.

- Now he can arise without falling: he stands upon his feet (v. 23) and is able to “labor without ceasing” (v. 24).

- His labor now is not destroying the church of God but bringing others to repentance, that they might also be born of God and be filled with the Holy Ghost (v. 24). Thus, instead of “murdering” others, he is giving them newness of life. Now “many have been born of God” because of his work (v, 26). In bringing souls to repentance, he is implicitly warning them of the destruction sin brings, as the angel warned him.

- In helping others enter into the covenant with God, he now has “exceedingly great joy in the fruit of my labors” (v. 25) instead of fear and horror.

- The role of the angel in speaking to Alma2 before is parallel to the function of the Holy Ghost and the Lord who fill Alma2 with great joy and impart God’s word to him (vv. 25–26).

Alma2’s fall to the dust, involving the spiritual death of his soul and the apparent physical death of his body (recall that dust/death form a Hebraic word pair22) are described in multiple, intertwined ways in the upper mid-section, and they are reflected in the description of Alma2’s new born-again state in the lower section.

In addition to several Hebrew word pairs mentioned in Part 2, one further word pair to consider is discussed by M. L. Barré in his treatment of Hosea 6:2,23 where he finds significance in the repeated pairing of “life” or chayah (חָיָה)24) and “rise” or quwm (קום). This may also be at play in Alma 36, though in a negative sense in v. 15, where Alma2 would rather have his life extinguished than to be called to stand in the presence of God. As part of item N in Welch’s outline, this links [Page 307]nicely to vv. 22–23, where Alma2 revives and stands again, though the connection between life/extinction and reviving/rising/standing is not made in Welch’s outline, suggesting that there may be more connections or strands to explore.

There are multiple dust-related concepts in Alma 36 (or rather, multiple motifs associated with rising from the dust as used in the Book of Mormon). These include Alma2’s transition from spiritual death to life, from sin to repentance, from destruction of the church of God to strengthening it, from fear and pain to joy, from murdering others (in a covenantal sense) to giving them life, all made possible by the divine grace initiated by the visit of an angel, amplified by the Holy Ghost, that this lost and fallen soul might rise from the dust literally and figuratively to be born of God. For these dramatic transitions, a complex, extended chiasmus is a beautifully fitting tool for artful expression by an author skilled in ancient Hebraic poetical techniques.

This set of motifs in Alma 36 invokes not only Lehi’s theophany and his dust-related preaching (treated in Part 2) but also the scene from the aftermath of King Benjamin’s speech in Mosiah 4, as the people fell to the earth and sought to apply the atoning blood of Christ to free them from their sins, resulting in great joy.

With the perspective that comes from understanding the Book of Mormon’s use of dust-related themes as introduced by Lehi and used multiple times right up to the closing page of the Book of Mormon, we find that an apparent gap in the otherwise brilliant chiasmus of Alma 36 becomes much more meaningful. A loose, sparse section in the first half previously mapped with only a few parallel words among many verses actually becomes a relatively tight cluster of intertwined themes, with almost every major concept reflected in the corresponding section below the pivot point. It can be remapped in multiple ways. For the overall structure, I’ll leave that as an exercise for the reader, though I prefer to leave it as a cluster of dust/death related themes above the pivot, and life/born again themes below the pivot. There are some individual mappings of thematic strands that I will share below.

Further Action at the Core of Alma 36

As for the chains of darkness in the Book of Moses that began this study and took me to the theme of rising from the dust, yes, chains are mentioned in Alma 36 but as “chains of death.” In fact, they are mentioned almost at the very pivot point of the chiasmus where Alma2 turns to Christ, after which Alma2 beholds light and experiences joy. [Page 308]With the contrast to light, Alma2’s chains of death are thus treated like chains of darkness:

18 Now, as my mind caught hold upon this thought, I cried within my heart: O Jesus, thou Son of God, have mercy on me, who am in the gall of bitterness, and am encircled about by the everlasting chains of death.

19 And now, behold, when I thought this, I could remember my pains no more; yea, I was harrowed up by the memory of my sins no more.

20 And oh, what joy, and what marvelous light I did behold; yea, my soul was filled with joy as exceeding as was my pain!

The encirclement of chains of death in Alma2’s dust-like state of spiritual death is later contrasted with another form of encirclement:

22 Yea, methought I saw, even as our father Lehi saw, God sitting upon his throne, surrounded with numberless concourses of angels, in the attitude of singing and praising their God; yea, and my soul did long to be there.

At the heart of the chiasmus, of course, are two references to Jesus Christ. Jesus, the Redeemer, is at the core of this chiasmus and at the core of the Book of Mormon. Here both instances of Jesus Christ are associated with terms relevant to the rise from the dust theme. The first is the word atone and the second is being encircled (by the chains of hell and darkness). A Hebraic wordplay may add further unity to this pivot point. The root for the verb “to atone” can be kaphar (כָּפַר)25). A word that can mean surround or encompass and thus possibly “encircle” is kathar (כָּתַר)26), differing from kaphar by one letter and sounding somewhat similar. Is there a Hebraic wordplay hidden at the center of Alma 36? If so, at the heart of the great chiasmus in Alma 36, we may have an additional parallelism:

Jesus Christ, a Son of God

to atone (kaphar) for the sins of the world

Jesus Christ, thou Son of GodHave mercy … encircled (kathar) by the everlasting

[Page 309]chains of death

Since the original Hebrew/Egyptian word order on the gold plates may differ from the English translation, it may be possible that verb to atone came before Jesus Christ to strengthen the chiastic structure, but in either case the apparent word play enhances the poetry and parallelism and enhances the significance of dust-related themes in a vital discourse of the Book of Mormon. The juxtaposition of Christ and His Atonement with the sins of the world and the everlasting chains of death bring polar opposites — or rather, cosmic opposites — together and reveal how Christ, through His sacrifice in which He voluntarily returned to the dust and took on the infinite burden that Enoch sensed, rose triumphantly and finally from the dust. He arose to break the chains of hell, to atone for the sins of the world, and to provide deliverance to all of us captives, one soul at a time, that we, too, might rise from the dust and sing the song of redeeming love (Alma 5:26) as we enter God’s presence, washed from the dust, freed from our chains, delivered from darkness and obscurity forevermore.

It is the voice from the dust (Isaiah 29:4; 2 Nephi 26:16, 27:9, 33:13; Moroni 10:27), the Book of Mormon, that so powerfully enlightens our understanding of Christ’s redemption and Atonement, enabling us to shake off the dust and arise.

Thematic Strands in Alma 36: Preliminary Thoughts

In addition to Welch’s mapping of Alma 36 that leaves some gaps where the chiasmic content seems sparse, the more densely packed content brought out by exploration of the Book of Mormon’s motif of rising from the dust with related thematic elements (keeping covenants, receiving glory and power, being revived or resurrected, or, as Alma2 puts it, born again) gives us more noteworthy parallels to consider.

One approach to mapping the additional content and structure it is to consider different strands of parallel structures almost as if they are themes in a fugue, weaving in and out of the main structure and not necessarily aligned with the primary pivot point. Thus, superimposed on the overarching structure Welch proposed, we may also add strands such as those in the following sections.

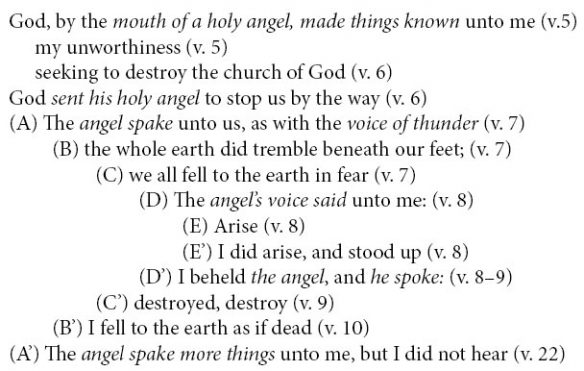

1. The Divine Voice Strand

Examining the references to the divine voice of an angel speaking to Alma2 in vv. 5–10 reveals an interesting parallelism with this theme, [Page 310]possibly including a five-step chiasmus embedded within the overall chiasmus. The parallelism partly relies on recognizing that falling to the earth is a symbol of destruction (returning to the dust, etc.) and that the trembling of the earth, another dust-related motif, can relate to falling to the earth and death.

For the Divine Voice strand, contrasts occur in the lower half of the overall chiasmus, with reference to the word of God that been has imparted to Alma2 (v. 26), the words he now imparts to others to bring them to God (vv. 23–26), and, of course, the voice of angels who are singing and praising God (v. 22) as well as his own praise of God (v. 28).

2. The Death and Destruction Strand

Three days and three nights –- like dead (v. 10)

loss of body functions (can’t speak, limbs don’t move, can’t hear) (vv. 10–11)

destroy, destroy (v. 11)

fear (v. 11)

amazement (v. 11)

destroyed (v. 11)*

torment for sins (v. 12)

remembered all my sins (v. 13)

murdered/destroyed others (v. 14)

rack my soul (v. 14)

inexpressible horror (fear) (v. 14)

extinction of body and soul (v. 15)

[Page 311]three days and three nights –- like dead (v. 16)

This could be formatted as a more conventional chiasmus with a stand-alone central unit instead of the three units of destroy themes followed by a pair of emotional response, though there may be other ways to parse this strand, if indeed it is an intentional strand or unit of some kind.

In any case, the three days and three nights as a symbol of death and revival merits consideration here as part of Alma2’s structure. It is a beautiful fit for the dust-related themes of the Bible and possibly the brass plates.

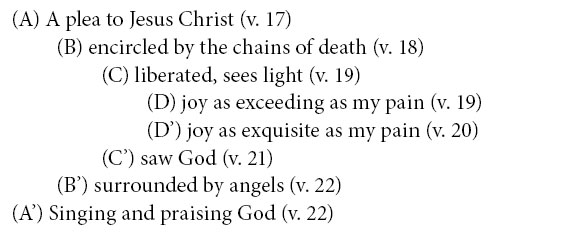

3. The Encircled/Surrounded Redemption Strand

A small chiasmus may be found in vv. 17–22 involving the theme of encirclement, and the liberation and joy that comes when negative encirclement is changed to positive, divine encirclement. The encirclement by chains in v. 18 is paired with being surrounded by angels in v. 22.

Once again, when the chains come off, there isn’t just light and joy, there is singing.

Alma 26:13 shows that when the “pains of hell” are loosed, the result is being “brought to sing redeeming love.” Like chains, the pains of hell in the Book of Mormon encircle victims (Alma 14:6) and need to be “loosed” (Jacob 3:11, Alma 26:13). Alma 36:13 refers to the “pains of hell” that Alma2 experienced, right before item N of Welch’s primary chiasmic structure. Following Alma2’s release from the pains of hell in the lower half of the chiasmus, v. 22, associated with item N’, also contains a reference to angels “singing and praising God.” No doubt it is the song of redemptive love they are singing. This linkage between singing and the pains of hell, adjacent to items N and N’, seems to strengthen the overall chiasmus.[Page 312]

4. The Rising Strand (emphasis on “rising / returning to the dust”)

The “Rising” strand looks at the chains as a potentially significant term linked to the motif of rising from the dust, and naturally also includes the “lifted up” and “raised up” passages at the ends. It is not a simple chiasmus but has inverted parallelism across several levels.

Like the main chiasmus, the “Rising” strand also works better if either of the phrases raised up or lifted up (at the last day) are moved slightly, for then two more elements fit a cleaner chiasmic structure (“trials, troubles, and afflictions” and also being “delivered”). Welch’s outline above labels the latter instance, item I’, as out of place, which is a logical suggestion for the overall structure, but the “Rising” strand [Page 313]works better if the first instance, “lifted up” in v. 3 is just moved up a few words in the text so that items I and H in the first part of the chiasmus are switched. It works better because it gives more emphasis to the theme of rising, putting it at the end points of the strand and closer to the end points of the main chiasmus.

5. The “Racked” Strand

In this strand, we use the occurrence of rack in Alma 36 with related terms in vv. 12–17 pointing to the horror and torment he faced, culminating in his desire for extinction. This strand has a chiastic flavor of its own, as noted above, and at its pivot point arguably draws upon the dust-related theme in which arising or standing (from Hebrew quwm) is linked in a Hebrew word pair to life, typically with life occurring first.27 In this case, though, both concepts are expressed negatively: he wishes not to have life in order that he might not be called to stand before God and be judged.

Racked / torment / harrowed / racked with all my sins (v. 12) + Tormented with the pains of hell (v. 13) for murdering God’s children (v. 14)

Did rack my soul (v. 14)

Yearns for extinction of soul and body (v. 15)

To not stand [linking “stand” with “life”] (v. 15)

Racked with the pains of a damned soul (v. 16)

Racked / torment / harrowed / my many sins (v. 17)

The intensification of his torment expressed powerfully in this strand brings us to the emotional climax in which he finally turns to Christ for mercy, bringing about the complete reversal as the chiasmus moves through the overall pivot point and away from a racked soul to a soul experiencing overwhelming joy.

Alma2’s wish for extinction and not standing in v. 15 also can be paired in the other half of Alma 36, as previously noted, with Alma2’s revival and standing upon his feet again in vv. 22–23. These concepts are in the vicinity of items N and N’ regarding the presence of God but again perhaps should be considered in light of dust-related concepts related to the word pair of life and arise.[Page 314]

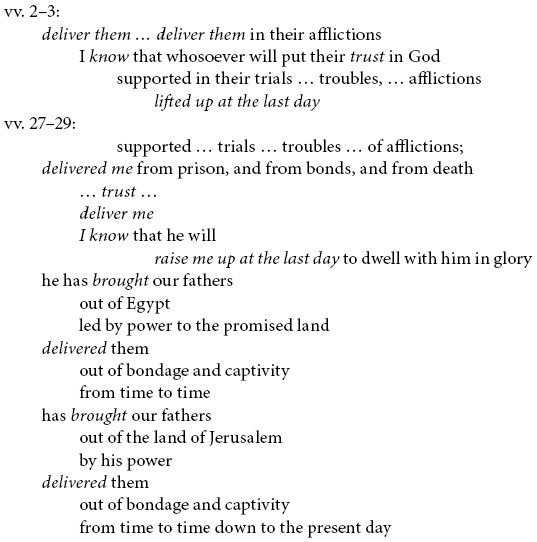

6. The Deliverance Strand

This strand involves vv. 2–3 and a pairing with vv. 27–29 toward the end of the chiasmus. It is in this section where we have the obvious interruption of the chiastic pattern with an apparently dislocated item I or I’ in Welch’s list and where one can complain of multiple occurrences of deliver that are not used. The “unexplained asymmetry” of item I is Wunderli’s first complaint, apparently not recognizing that occasional out-of-place elements are common in the literature and may occur for a variety of reasons, especially when conveying narrative content that simply may not elegantly fit the overarching chiastic framework. Translation itself may force some elements into new orders. However, more complex poetical structures may create the appearance of out-of-place elements.

Are the extra instances of deliver in these verses wasted, contributing no more to the poetical structure than mere repetitious words for a crafty apologist to select and label creatively? A look at their structure suggests something more may be present.

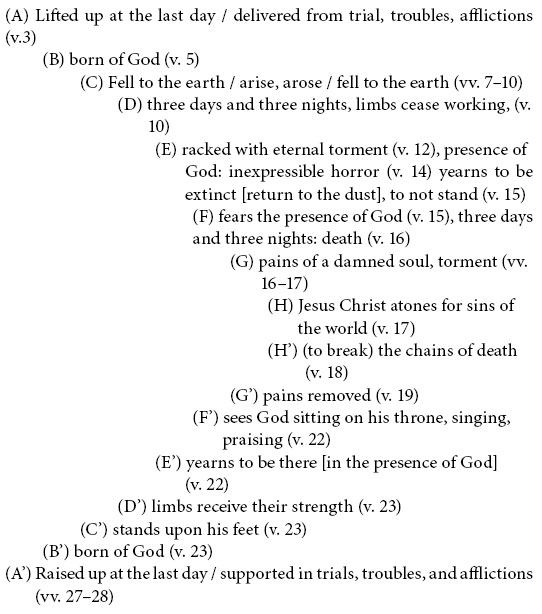

The relevant verses are mapped as follows by Welch:

In this strand, we examine the other occurrences of deliver and some other words that are not used in Welch’s mapping. This segment begins with remembering the captivity and bondage of the Nephite’s ancestors and ends with bondage, captivity, and remembrance. Now consider [Page 315]some key terms in the interior text, where related passages have been given similar indentation:

In vv. 2–3 we have two instances of deliver followed by trust in God and the combination of supported/trials/troubles/afflictions that firmly highlights a key element in the overall chiastic pairing. Then comes the ultimate aim of deliverance, being “lifted up at the last day” from the end of v. 3.

Looking exclusively at the usage of deliver, another structure points to the personal application of God’s deliverance of the fathers, turning from how God “delivered them” to how God can “deliver me” in the center of this strand:

Deliver them / deliver them

Delivered me / deliver me

Delivered them / delivered them

[Page 316]In addition to four more instances of deliver in vv. 27–29, a related term from the Exodus account is introduced: brought out (a partial list includes Exodus 3:8, 10; 6:6; 12:17, 42, 51; 13:9, 14, 16; 16:32; 32:1, 7, 8, 11, 23; 33:1; Leviticus 23:43; 25:38, 42; 26:13; Deuteronomy 4:37; Hosea 12:13; cf. 1 Nephi 17:14, 40; 2 Nephi 25:20). Used twice, each occurrence of brought out is followed by a place (Egypt or Jerusalem) and a reference to God’s power in bringing them out (and to the Promised Land, explicitly or implicitly). It is then followed by the statement that God has “delivered them out of bondage and captivity from time to time,” with the last statement following the pattern of personalizing the past by bringing the lessons of deliverance up “to the present day” (v. 29).

There are two different Hebrew words used in the above-mentioned kjv verses for brought out. The first is the Hebrew root yatsaʾ (יצא)28), “to go out,” used in Exodus 3:10; 6:6; 12:17, 42, 51; 13:9, 14, 16; 16:32; 32:11; Leviticus 23:43; 25:38, 42; 26:13; and Deuteronomy 4:37.29 The other is the Hebrew root ʿalah (עלח)30), “to go up,” used in Exodus 3:8; 32:1, 7, 8, 23; 33:1; Hosea 12:13 (the kjv has Hosea 12:13, while the Hebrew text has Hosea 12:14). In some of these verses, the Hebrew root natsal (נצל)31), “to deliver” is also used (e.g., Exodus 3:8, 6:6).

Focusing on the combined use of deliver and brought out in these verses, a richly parallel structure emerges with numerous terms involved, including all the instances of deliver in these verses:

A1. Deliver them / deliver them / know / trust / lifted up at the last day (2–3)

A2. Deliver me / trust / deliver me/ know / raise me up at the last day (27–28)

B1. Brought our fathers / out of Egypt / led by power to the promised land

C1. delivered them / bondage and captivity / from time to time (28)

B2. Brought our fathers / out of the land of Jerusalem / by his power

C2. delivered them / bondage and captivity / from time to time down to the present day (29)

[Page 317]This strand begins in the first half of the primary chiasmus but amplifies the deliverance theme in the second half while still leading to the chiastic link to bondage, captivity, and remembrance between the first and second halves. Verses 27–29, sometimes said to be merely repetitious text making alleged chiasmic poetry the workings of chance and cherry picking, reveal a rich poetic structure consistent with ancient Hebrew parallelism and the frequent deviations from simple, linear introverted parallelism.

The proposed strands in Alma 36 are crude initial efforts. They may not be intentional and could be wishful thinking on my part, but they may reflect some additional structure, including some additional chiastic structure, embedded in Alma 36. In any case the rising from the dust theme of the Book of Mormon seems to be a potentially important lens to aid understanding of some of its passages, including Alma 36. It seems that Nephi was keenly aware of those themes in the way he framed Lehi’s speech in an inclusio with unusual redundancy from Isaiah followed by a nice build to the critical passage of Isaiah 52:1–2.

Conclusion

In this three-part study, an investigation of Book of Moses themes that might have been present on the brass plates led to a variety of tentative discoveries involving a complex of themes or motifs tied to rising from the dust, including escape from the captivity and chains of Satan, covenant keeping, resurrection, enthronement, encirclement (arms of God’s love, robes of righteousness), and entering the presence of God. These themes reveal added meaning in several significant portions of the Book of Mormon, including the chiasmus of Alma 36, and further illustrate the power of the Book of Mormon as a voice from the dust calling us to rise from the dust and receive the full blessings of the Atonement of Christ.

In Alma 36, Alma2’s contrast between falling to the earth, like dead, and then being born again and freed from the chains of death also suggests awareness and intelligent use of those concepts from Nephi, Isaiah, and perhaps elsewhere on the brass plates. Dust-related themes help us identify multiple structural elements worthy of consideration in passages once thought to be diffuse with a relatively weak role in Alma2’s parallelism. However you map it or unpack it, there is a great deal of interwoven structure in Alma 36 with more richness there than we may have realized. This is true for the entire Book of Mormon. What a remarkable voice from the dust![Page 318]

1. John W. Welch, ed., Chiasmus in Antiquity: Structures, Analyses, Exegesis (Hildesheim, Germany: Gerstenberg Verlag, and Provo, UT: Research Press, Brigham Young University, 1981). Valuable resources for research and understanding of chiasmus are at http://chiasmusresources.johnwwelchresources.com, including details of chiasmus in the Book of Mormon, the Bible, some Mesoamerican literature, etc. as well as information on criteria for identifying deliberate chiasmus.

2. John W. Welch, “Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon,” BYU Studies, 10/1 (1969): 1–15; https://byustudies.byu.edu/article/chiasmus-in-the-book-of-mormon.

3. Wilfred G.E. Watson, “Chiastic Patterns in Biblical Hebrew Poetry,” in Welch, ed., Chiasmus in Antiquity, 118–168.

4. Radday, “Chiasmus in Hebrew Biblical Narrative,” in Welch, ed., Chiasmus in Antiquity, 50–117.

5. Robert Lowth, De Sacra Poesi Hebraeorium Praelectiones Academicae (Oxford: Clarendon, 1753). Also Robert Lowth, Lectures on the Sacred Poetry of the Hebrews, translated by G. Gregory (Boston: Crocker & Brewster and New York: J. Leavitt, 1829); available at Archive.org, https://archive.org/details/lecturesonsacred00lowtrich. Lowth’s work highlighted several forms of parallelism, but overlooked the introverted parallelism that is the basis of chiasmus. See Radday, “Chiasmus in Hebrew Biblical Narrative,” 50. Also see John W. Welch, “How Much Was Known about Chiasmus in 1829 When the Book of Mormon Was Translated?,” FARMS Review of Books 15/1 (2003): 47–80; https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1503&context=msr.

6. Radday, “Chiasmus in Hebrew Biblical Narrative,” 50–112.

7. Bokovoy discusses two attempts at using chiasmus to defend the unity of the flood narrative in Genesis in Bokovoy, Authoring the Old Testament. The analyses of chiasmus include G.J. Wenham, “The Coherence of the Flood Narrative,” Vetus Testamentum 28 (1978): 336–48 and F.I. Andersen, The Sentence in Biblical Hebrew (The Hague, Netherlands: Mouton Publishing, 1974), 39–40, 59. The later, according to Bokovoy, is rebutted in J.A. Emerton, “An Examination of Some Attempts to Defend the Unity of the Flood Narrative in Genesis: Part II,” Vetus Testamentum 38 (1988): 1–21, and the very different chiastic structures proposed by Wenham and Andersen suggests to Bokovoy that the alleged chiastic structures are subjective. For a more positive discussion of the significance of parallelism in the flood story, see Robert B. Chisholm Jr., “Old Testament Source Criticism: Some Methodological Miscues,” in James K. Hoffmeier and Dennis R. Magary, ed., Do Historical Matters Matter to Faith? A Critical Appraisal of Modern and Postmodern Approaches to Scripture (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2014), 181–99.

8. John W. Welch, “Criteria for Identifying and Evaluating the Presence of Chiasmus,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 4/2 (1995): 1–14; https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1072&context=jbms.

9. Boyd F. Edwards and W. Farrell Edwards, “Does Chiasmus Appear in the Book of Mormon by Chance?,” BYU Studies 43/2 (2004): 103–30; https://byustudies.byu.edu/article/does-chiasmus-appear-in-the-book-of-mormon-by-chance.

10. Ibid.

11. John W. Welch, “A Masterpiece: Alma 36,” in Rediscovering the Book of Mormon, ed. J.L. Sorenson and M.J. Thorne (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1991), 114–31; https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?filename=11&article=1064&context=mi&type=additional, accessed Jan. 25, 2016.

12. Jeff Lindsay, “Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon,” JeffLindsay.com; http://www.jefflindsay.com/chiasmus.shtml.

13. Earl M. Wunderli, “Critique of Alma 36 as an Extended Chiasm,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 38/4 (Winter 2005): 97–110; http://www.dialoguejournal.com/wp-content/uploads/sbi/articles/Dialogue_V38N04_105.pdf. A preliminary response to Wunderli was given by B. F. Edwards and W. F. Edwards, “Response to Earl Wunderli’s critique of Alma 36 as an extended chiasm, Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 39/3 (2006): 164–69; http://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1572&context=physics_facpub, accessed April 19, 2016. Related objections to Alma 36 as a chiasmus are offered in Robert M. Bowman Jr., “Alma 36: Ancient Masterpiece Chiasmus or Modern Revivalist Testimony?,” Institute for Religious Research, https://irr.org/alma-36-ancient-masterpiece-chiasmus-or-modern-revivalist-testimony, accessed Aug. 20, 2016.

14. Welch, “A Masterpiece: Alma 36.”

15. Donald W. Parry, Poetic Parallelisms in the Book of Mormon: The Complete Text Reformatted (Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute, Brigham Young University, 2007), 318–21; https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi/61/.

16. Wunderli, “Critique of Alma 36 as an Extended Chiasm,” 104.

17. Ibid., 102.

18. Brueggemann, “From Dust to Kingship.”

19. Ibid.

20. J. Wijngaards, “Death and Resurrection in Covenantal Context (Hosea VI 2),” Vetus Testamentum 17, Fasc. 2 (April 1967): 226–239; available at Jstor.org: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1516837, accessed Dec. 16, 2015.

21. See the discussion of the Hebrew word for “arise,” quwm (קום), HALOT 1086–1088, in Part 2.

22. Kevin L. Barney, “Poetic Diction and Parallel Word Pairs in the Book of Mormon,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies (1995).

23. M. L. Barré, “New Light on the Interpretation of Hosea VI 2,” Vetus Testamentum 28, Fasc. 2 (April 1978): 129–41; http://www.jstor.org/stable/1516963.

24. HALOT, 309–10. See also Strong’s H2421, Blue Letter Bible; https://www.blueletterbible.org/lang/lexicon/lexicon.cfm?Strongs=H2421&t=KJV.

25. HALOT, 493–94. See also Strong’s H3722, Blue Letter Bible; https://www.blueletterbible.org/lang/lexicon/lexicon.cfm?Strongs=H3722&t=KJV.

26. HALOT, 506. See also Strong’s H3803, Blue Letter Bible; https://www.blueletterbible.org/lang/lexicon/lexicon.cfm?Strongs=H3803&t=KJV.

27. Barré, “New Light on the Interpretation of Hosea VI 2.”

28. Strong’s H3318, Blue Letter Bible; https://www.blueletterbible.org/lang/lexicon/lexicon.cfm?Strongs=H3318&t=KJV.

29. Many thanks to Kevin L. Tolley for this information and for assistance with Hebrew roots in many sections of this series.

30. Strong’s H5927, Blue Letter Bible; https://www.blueletterbible.org/lang/lexicon/lexicon.cfm?Strongs=H5927&t=KJV.

31. Strong’s H5337, Blue Letter Bible; https://www.blueletterbible.org/lang/lexicon/lexicon.cfm?Strongs=H5337&t=KJV.

Go here to see the 11 thoughts on “““Arise from the Dust”: Insights from Dust-Related Themes in the Book of Mormon (Part 3: Dusting Off a Famous Chiasmus, Alma 36)”” or to comment on it.