Abstract: Many Latter-day Saint scholars recognize that an excellent candidate for Nephi’s Bountiful is found at the inlet Khor Kharfot in southern Oman at the end of the lengthy Wadi Sayq. Many researchers have reasonably assumed that Lehi’s eastward travel from Nahom must have led to Wadi Sayq, which then leads directly to Khor Kharfot. However, there is a second route, through Wadi Kharfot, that leads to Khor Kharfot, joining Wadi Sayq near the inlet. Although almost unknown, this second wadi could also have offered a plausible route with some advantages to travelers arriving from the interior desert plateau. Specifics and details of terrain, distances, and directions are presented to support seriously considering this new proposal.

Since its discovery in the mid-1980s during a multi-year ground search of the entire southeastern coast of Arabia, the inlet of Khor Kharfot in Dhofar, southern Oman, has been the candidate favored by most Book of Mormon researchers for the ease in which it uniquely meets all the detailed descriptors of Bountiful embedded in Nephi’s text.1 Nephi was very clear in the directions he gave—most importantly, that Bountiful lies “nearly eastward” from Nahom:

And it came to pass that we did again take our journey in the [Page 430]wilderness; and we did travel nearly eastward from that time forth. And we did travel and wade through much affliction in the wilderness. . . . And we did come to the land which we called Bountiful. . . . And we beheld the sea, which we called Irreantum, which, being interpreted, is many waters. And it came to pass that we did pitch our tents by the seashore. (1 Nephi 17:1, 5–6)

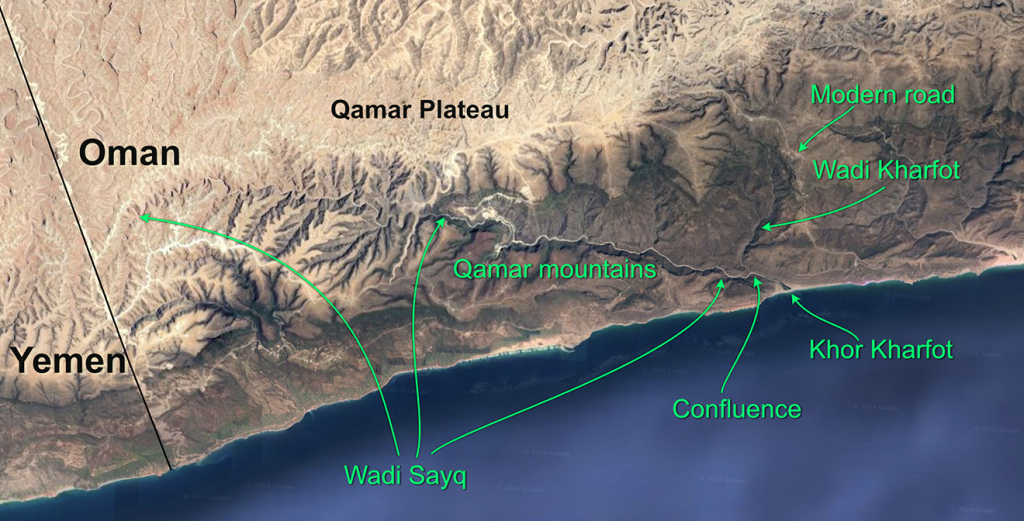

Figure 1 is an overview of the proposed area in which the final stage of the Lehite journey took place. It illustrates that both Wadi Sayq and Wadi Kharfot lead directly into Khor Kharfot, the leading candidate for Bountiful. It also shows the plateau from which both wadis originate. This penultimate leg of the Lehite group’s difficult journey across Arabia—plausibly around two years of travel to cover the approximately 2,100 miles (3,400 km) from Jerusalem—was also its main directional change.2 Following Ishmael’s burial at Nahom, the group headed “nearly eastward from that time forth” (1 Nephi 17:1), eventually bringing them to Irreantum, the great ocean, where the place they named Bountiful awaited.3

The Presence of Two Wadis

Not all students of Nephi’s journey across Arabia may realize that there are actually two wadis, or river valleys, providing access for the final stage of travel from the interior deserts into Khor Kharfot. Both wadis converge near the beginning of the inlet. Wadi Sayq is the best known, with a long pathway spanning 23 miles (38 km). It leads from [Page 431]the modern border between Yemen and Oman down through the Qamar mountains, until it reaches the inlet of Khor Kharfot. On-site exploration and high-resolution satellite imagery has shown the prominent Wadi Sayq to be a plausible, reasonable path for an ancient group reaching Khor Kharfot as they came from the west. While Wadi Sayq could have been the path that Lehi used, it need not be the only plausible candidate.

Figure 1. Satellite view of Qamar mountains highlighting Wadi Sayq, Wadi Kharfot, and Khor Kharfot. Image courtesy of Google Earth.

Continuing exploration by the author over recent years has led to the recognition that Wadi Kharfot, the other wadi that arrives at the beginning of the inlet of Khor Kharfot, merits consideration alongside Wadi Sayq as a candidate for part of Lehi’s journey to Bountiful. With this in mind and rethinking earlier assumptions, in 2020 the author began a focused examination of Wadi Kharfot. The study and exploration was completed in 2024. Wadi Kharfot is narrower and shorter, just 7.5 miles (12 km) in length. It meets Wadi Sayq at the inland end of the inlet, just some 1.17 miles (1.88 km) from the shoreline. Interestingly, Wadi Kharfot can be said to roughly mean “Abundance [of fruit] Valley.”4

Wadi Kharfot turns out to represent an attractive second possibility for accessing Khor Kharfot. Wadi Kharfot potentially offers a substantially more direct, much-less-difficult access to the ocean than its [Page 432]longer sister-wadi. This study compares these two wadis that jointly reach Khor Kharfot, proposing that this second wadi is not only a viable route, but may have provided an advantage to the Lehite group over Wadi Sayq by offering them a faster final stage of travel. Figure 2 provides an aerial view of the meeting of the two wadis at the entrance to the inlet of Khor Kharfot. Figure 3 provides a close-up version of that meeting point.

Figure 2. Wadi Sayq and Wadi Kharfot arriving at Khor Kharfot. Image from Google Earth.

Figure 3. Close-up view of Wadi Sayq (from the lower left side of this image) and the narrower Wadi Kharfot, converging at Khor Kharfot inlet. Image from Google Earth.

[Page 433]It has long been customary in Latter-day Saint commentary (including by this author) and, in academic studies, to speak of Khor Kharfot as being the “end” of Wadi Sayq, or as being an extension of it. More accurate descriptive terminology should acknowledge that Khor Kharfot begins where two wadis, Wadi Sayq and Wadi Kharfot, converge, terminating at Khor Kharfot. An inlet is defined as being the extent of the original bay; in other words, it is where the ocean has, and sometimes still does, reach inland. Though there is not a precise point where a wadi ends and an inlet begins, the furthermost inland point of Khor Kharfot can be estimated to be at or near the region where both wadis meet.

Differences between the Two Wadis

The differences between the two wadis are significant. The first difference is their respective positions in the landscape. Figure 1 illustrates how travelling eastward from Yemen’s Mahra plateau into the Qamar region of Oman offers two very different routes to reach the inlet of Khor Kharfot. Wadi Sayq immediately plunges into the midst of the corrugated and steep Qamar mountains, winding eastward in a gradual descent toward the coast. In contrast, anyone arriving just a short distance north of Wadi Sayq enters a long undulating plateau that skirts the northern side of the Qamar mountains, avoiding them altogether. This plateau allows an eastward journey through easy terrain, followed by a short south-trending pathway to the inlet.

The physical structure of the wadis differs

As noted earlier, Wadi Kharfot is 7.5 miles (12 km) long, or less than a third of the length of Wadi Sayq’s 23 miles (38 km). It meanders less than does Wadi Sayq, and its base is also narrower. (Wadi Sayq is shown in figure 4.)

The terrain surrounding the newly considered entrance to the inlet of Wadi Kharfot is shown in figure 5. That wadi has several shallow paths leading into it at the beginning of its descent toward the ocean.

Finally, with the modern road to Rakhyut roughly following its contours for about two thirds of the distance, Wadi Kharfot descends to the Khor Kharfot inlet through much lower surrounding terrain than does Wadi Sayq (see figure 6).

[Page 434]

Figure 4. A representative view of Wadi Sayq, facing eastward, just a few kilometers from its arrival at Khor Kharfot. Photograph by the author.

Figure 5. A view of Wadi Kharfot showing its base and the surrounding terrain, facing inland. Photograph by the author.

Figure 6. This view of Wadi Kharfot, facing the ocean, shows some of the shallow entrances into the wadi as it commences its descent toward Khor Kharfot. Photograph by the author.

The natural function of each wadi differs

Wadi Sayq is the primary drainage for the Qamar ranges, a sizeable [Page 435]block of mountainous terrain stretching east from the Mahra province of Yemen almost to Mughsayl, in Oman. Dozens of tributary wadis feed their runoff into Wadi Sayq, which means that during and following the monsoon rains, the wadi has long had a substantial amount of water flowing through it toward the coast. The scouring of rocks at the base of the wadi over thousands of years can easily be seen today.

In contrast with Wadi Sayq, Wadi Kharfot receives very limited water runoff from its surroundings. With a single small tributary wadi feeding into it on its west side, its water levels are significantly less than in Wadi Sayq.

The huge amount of water coursing through Wadi Sayq for several months of each year has, over millennia, resulted in an accumulation of huge boulders shortly before its very end at the beginning of the inlet.5 However, this accumulation of boulders need not have prevented people and animals from entering the inlet of Khor Kharfot in ancient times. Based on my fieldwork, even though the boulders may be more numerous today than anciently, they extend for only a short distance, [Page 436]and it is not overly difficult to pick one’s way past them along the side of the wadi. Locals regularly do this as they bring cattle, goats, and camels to graze in the inlet.

On the other hand, while Wadi Kharfot certainly has boulders along its length, there is no appreciable accumulation of rock debris at any point. The point is that the rocks in Wadi Kharfot present less hindrance to travel than do the ones in Wadi Sayq.

These differences between the two possible pathways to the coast mean that arriving via Wadi Kharfot, rather than via Wadi Sayq, would involve faster travel because of the less-difficult terrain leading to the entrance to the wadi, plus the considerably shortened length of the wadi itself.

Similarities in the Two Wadis

Both wadis are readily accessible at their very beginnings inland, and both become gradually descending conduits toward the ocean. In the case of Wadi Sayq, the sides of the valley are often very steep and even convex in places. This means that entering the wadi can only be done at its beginning because of the natural barrier presented by those valley walls. While Wadi Kharfot runs between much lower hills for its entire length, entry into it is also most likely to occur at its beginning.

In late September 1993, the author and his team were granted a permit to access the beginning of Wadi Sayq, located in a military area, just meters from the Yemen border. While the visit was necessarily brief and the team’s vehicle was not allowed to stop at any point, it nevertheless allowed the team to confirm that Wadi Sayq could be easily and simply accessed from the Qamar plateau through low, gently rolling terrain. Within a short distance, however, the walls on each side of the wadi became “too convex and deep to enter.”6

Satellite imagery has become available at a resolution where the literal commencement of Wadi Sayq can be seen clearly.7 As of 2024, while the general lay of the land where Wadi Sayq begins is clear enough, continuing road construction at various sections of the wadi have somewhat obscured its very beginning in updated satellite [Page 437]imagery. On the other hand, the commencement of Wadi Kharfot remains clearly visible and undisturbed, both on the ground and viewed remotely.

Wadi Sayq channels most of the rain that falls over the Qamar mountains downstream to its outlet, Khor Kharfot, thus providing this one coastal bay with a level of fertility—including timber species—unique among the inlets of the entire Arabian coast. It should also be noted that the Khor Kharfot inlet additionally receives a considerable amount of water directly from its surrounding hills. Although the drainage offered by Wadi Kharfot is relatively insignificant; the smaller wadi may have also played a significant, albeit quite different, role by providing shorter access to the inlet for the Lehite group. Figure 6 shows that Wadi Kharfot is quite narrow as it wends its way toward the inlet of Khor Kharfot.

Otherwise, the sparse details of the arrival at Bountiful recorded by Nephi do not favor either of the two wadis. In particular, travel through either wadi results in what Nephi’s text suggests—that the group did not see the great ocean until they emerged into Khor Kharfot and pitched their tents “by the seashore” (1 Nephi 17:6). Regardless of which access wadi was used, the great ocean—called “Irreantum” by Nephi (1 Nephi 17:5)—remained firmly out of sight, hidden by the surrounding terrain until they emerged into Khor Kharfot with its unique resources, towered over by the nearby mountain that came to play a key role as Nephi sought revelatory guidance (accounts beginning with 1 Nephi 17:7).

Conclusions

Many readers and commentators of Nephi’s account have noted that the exuberant rejoicing captured in 1 Nephi 17:5–6 largely resulted from the “much fruit” being visibly abundant and accessible as they arrived, becoming the primary reason for the group naming the place Bountiful. This is important, because it virtually requires that the arrival at Bountiful came soon after the completion of the monsoon rains, in other words, mid-September to late-October, when the vegetation was at its most abundant.

Providentially, for a group exhausted from the deprivations of the most difficult stage of their land travel, the essentials of life—food, water, and shelter—were truly optimal. In addition to food and water resources, there would likely have been no need to change from tent living on the seashore for several months. From about April onwards, [Page 438]increasing wind and rain from the approaching monsoon season would require more durable homes in a less exposed part of the inlet or the use of natural protection such as caves.

Realities on the ground—most still visible today—thus continue to inform our quest to probe these sacred records. They bring us closer to a fuller appreciation of what is surely one of the longest and most consequential journeys in history. Specifics such as the terrain, distances, directions, and so on—embedded in Nephi’s text and discussed here—offer further compelling support for it being a history of real people on a real journey. This author believes that all further studies involving the Old World Bountiful, and the Lehite journey across Arabia, should take into account this new possibility in any discussion of the route traveled.

Go here to see the 3 thoughts on ““Accessing Nephi’s Bountiful: A New Proposal for Reaching Irreantum”” or to comment on it.