Abstract: A revealing analysis of fish iconography in Mesoamerica, in relation to the ancestral couple on Stela 5, Izapa, Chiapas, Mexico, holds an unforeseen element that may reveal a key to the Tree of Life referred to in the Book of Mormon. This key is supported by Mesoamerican, Hebrew, and Egyptian traditions.

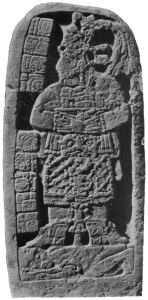

There have been numerous illustrations of Stela 5, Izapa, since its discovery in 1941 by the National Geographic Society and the Smithsonian Institute. However, the latest examination of this stela with reflective or reflectance transformation imaging (RTI) technology provides evidence that the most precise drawing is Garth Norman’s rendition in 1976.1 The RTI method is based on taking numerous photographs of a surface with a low-angle light source placed in many different locations, creating a compilation of images that can be analyzed by computer to create an accurate representation of the surface topography.2 RTI has now been used in numerous archaeological [Page 52]contexts.3 Laser scanning can produce similar results, but it has not yet been permitted by authorities in Mexico for Stela 5. The RTI evaluation of Stela 5 was conducted in 2013 by Jason B. Jones, then a researcher at the University of Warwick, who presented the work with Garth Norman at the Society of American Archaeology.4

The consensus of opinion for dating Stela 5 in Izapa lies between the Middle Preclassic to the Late Preclassic, around 400 to 50 BC. It is very difficult to accurately date stone unless there is a phonetic writing system on or nearby, which was not developed at this time. The date established by Garth Norman is 500–400 BC.5 Norman researched this stela for almost 58 years. Stela 5 has one of the earliest depictions of fish in Mesoamerica. As will be demonstrated, the symbolic meaning of some fish patterns lasted more than a thousand years in Mexico and Central America.

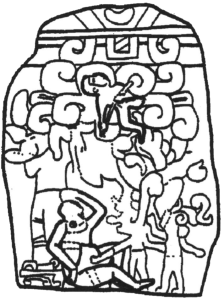

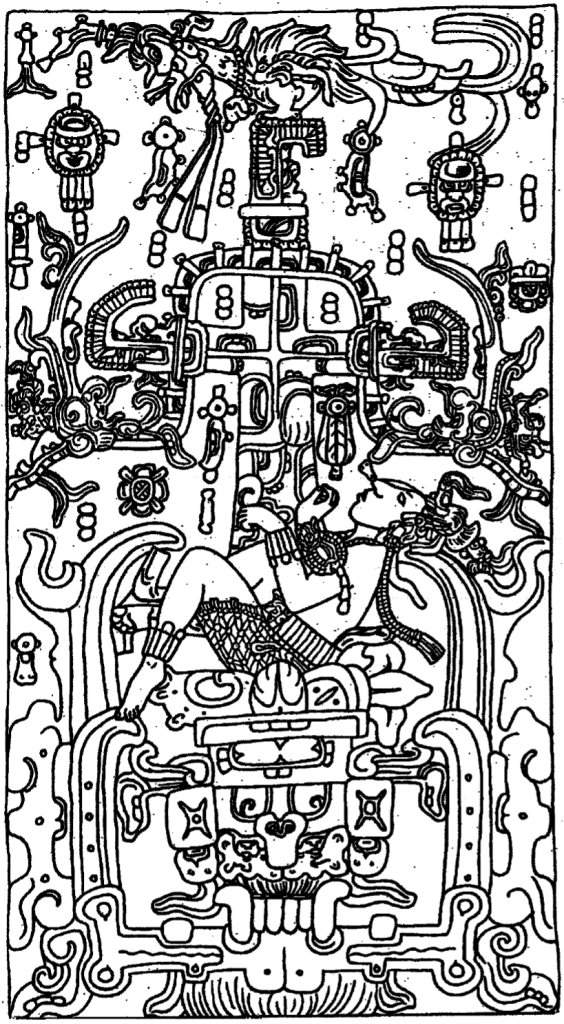

For a detailed illustration of Stela 5, see figure 1.6 This stela is a complex, low-relief illustration depicting in a narrative style many unusual animals, people, items, and the World Tree or Tree of Life. Trees are often related to creation in Mesoamerica.7 Our attention will be the fish on Stela 5: two fish are to the left of the tree and above the smoke of an incense burner, and two fish hang at the top of the stela to the far left of [Page 53]the celestial band. The celestial band or “skyband” enables the viewer to visualize this story in stone beyond the natural realm.8

Figure 1. Garth Norman’s 1976 illustration of Stela 5, Izapa, Chiapas, Mexico.

Two Fish on Stela 5

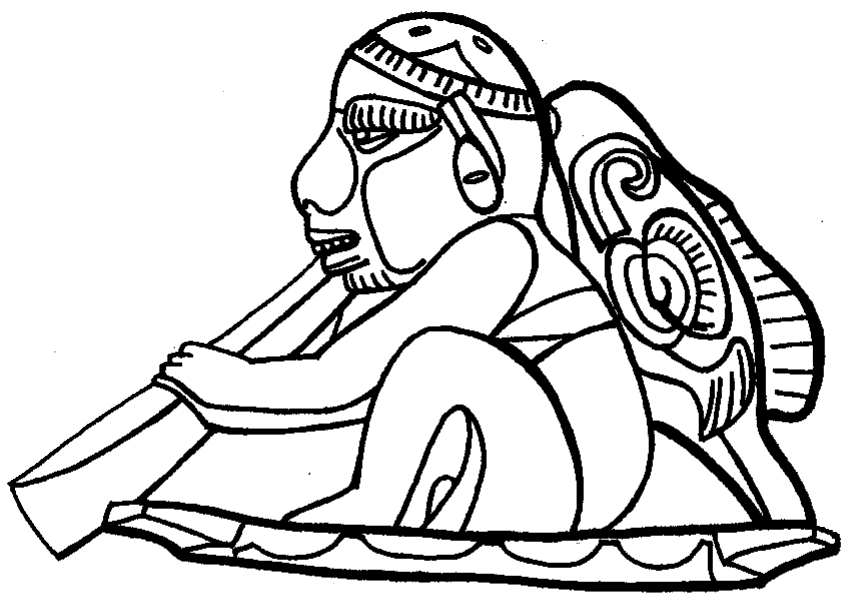

Figure 2. Fish with breath beads.

The two fish rising from the smoke and ascending towards the skyband have what is known as a “breath bead” at the tip of their mouths, as shown in figure 2. Some have surmised this round object is a fruit from the Tree of Life. If so, it may have a dual meaning, which could be construed as having a parallel connotation for the end of a life’s cycle. The breath bead is unique; it appears only on deceased high-ranking individuals, never on fish. This strange occurrence appearing on fish, and what these fish on Stela 5 imply, will be addressed shortly.

Figure 3. Lineage founder K’inich Yax K’uk’ Mo’, Altar Q, Copan, Honduras. (Drawing by the author after Schele and Mathews, The Code of Kings, 134.)

[Page 54]Among both the Olmec and later Maya, a bead may appear in front of a nose depicting the deceased.9 For example, Altar Q in Copan, Honduras, is a four-sided structure showing four rulers on each side, dating from the early fifth to mid-eighth century AD. Each has a breath bead in front of its nose, as shown in figure 3.10 The bead, usually of precious jade, was considered the soul or spirit of the deceased.11 This practice endured from the Preclassic to the arrival of the Spanish—over 1,500 years. According to Allen Christenson, “breath” is figurative of “spirit,” and refers to a person’s “life force.”12

Inasmuch as the soul is being captured when an individual dies, the two fish on Stela 5 may represent human personages, which is the hypothesis presented in this study. The two fish at the top and positioned at the bottom of the celestial band are directly in line over the figures of two ancestral parents who may be Sariah and Lehi. These early progenitors in the Book of Mormon have been suggested by several Latter-day Saint researchers, but not necessarily related to the fish. The first to propose the identification of the figures at the bottom on both sides of the tree was Wells Jakeman, founder of the archaeology department at Brigham Young University.13 Not all Latter-day [Page 55]Saint scholars agree on this couple’s early identity. For the sake of discussion, however, it will be assumed this theory is correct.

Fish Symbolic of Birth

After comparing evidence gathered by researchers, Douglas Gillette concluded:

[W]e now know that the Maya believed the soul had a life cycle that began in paradise, continued on the earth plane as its participation in the struggle to defeat and absorb the forces of destruction and death, and that was intended to end in an eternal celebration of life and Being. The soul determined its own ultimate fate by how well it constructed a durable “Resurrection Body” during its sojourn on earth.14

Souls were sent to mortals by heavenly gods, considered a creator couple.15 Lewis Spence researched the Aztec couple Xochiquetzal and Xochipilli, viewed as jointly one, and remarked that they “must be regarded as the direct creators of the spirit of man . . . and must be comprehended as sending the human soul to occupy the body made by human procreation, giving warmth and breath to the infant before birth.”16 His remarks drew upon the work of German archaeologist Eduard Seler, who said that “Xochipilli, God of Flowers, the male counterpart of the goddess Xochiquetzal . . . is supposed to dwell in the uppermost heaven, to send children thence into the world.”17 This sounds familiar to Latter-day Saints who believe in the pre-existence of children born to heavenly parents before their mortal birth.

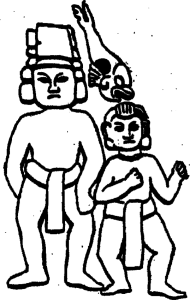

Figure 4. Altar O, Copan, Honduras. (Drawing by the author after Maudslay, Biologia Centrali-Americana, vol. 1, pl. 85.)

A scene on Altar O at Copan, Honduras, displays this tradition (see figure 418). A fish is directly over a child standing next to his father. The [Page 56]fish represents the child’s soul, making his association with birth and lineage apparent. Some scholars propose there is a ruling fish family at Copan.19 The father figure rests his hand on his thigh, which is a recognized symbol of fertility in Mesoamerica.20

Another depiction of this theme, corroborating this concept without a fish, is in a pre-Columbian book called the Borbonicus Codex, compiled by the Aztec in 1507 (see figure 521). This picture of the woman wearing the skin of a flayed sacrificial person is abhorrent to us, but for the people of ancient Mexico it gave a visual picture providing important elements. The soul of a child descends from heaven in a pre-mortal state to its pregnant mother, and is simultaneously born. The earliest depiction of birth from the heavens is Stela 10 at Izapa (see figure 6). Emphasis is on the main figures: a pre-existent child above, and a mortal female below.22

Figure 5. Child descends to its mother, who gives birth. (Drawing by the author after Codex Borbonicus.)

Figure 6. Child descends for birth (with emphasis), Stela 10, Izapa. (Drawing by the author after Norman, Izapa Sculpture, Part 2, 109.)

Figure 7. Shark-fish head and shell on apron of a woman, stela 24, Naranjo, Guatemala. (Drawing by the author.)

A comment by Karl A. Taube, a professor specializing in Mesoamerican archaeology and iconography, is important in relation to fish and birth.23 He postulates that the famous mythological mural at Teotihuacan, Mexico, depicts fish and writes that they may represent “not humans turned into fish, but fish before they became humans.”24 The fish most likely represented ancestors as they swam to the “present human world.”25 There is no doubt that fish and birth are interwoven in Mesoamerican tradition. Several stelae among the Maya portray women with a highly stylized shark head, a type of fish, placed on the abdomen area of their apron, the fish head representing an embryo (see figure 7). Below the fish head is the design of a shell. This may symbolize the womb, the place where a child will be formed waiting for birth.26 Stela 24 from Naranjo, Guatemala, with this type of apron, commemorates a woman from Naranjo marrying a Tikal king [Page 58]and giving birth to their son (see figure 827).

And from the Maya Dresden Codex, a newborn human emerges from a shell with a deity above (see figure 9). Eric S. Thompson wrote, “[J]ust as the fish issues from a shell, so emerges man from the womb of his mother.”28 Considering a shell may represent birth, there is a shell containing a spiral design just below the two hanging fish on the celestial band of Stela 5 (see figure 1). This shell would also have the meaning of birth, and in this case, to a state of rebirth.

Figure 8. Stela 24, Naranjo, Guatemala. (Photograph from Wikimedia Commons.)

Figure 9. Man emerges from shell. (Drawing by the author after Dresden Codex.)

Fish Symbolic of Death and Rebirth

Figure 10. Aged man in shell of rebirth, Uaxactun, Guatemala. (Drawing by the author.)

Taube points out the Maya group called Chorti, considered the people who were destroyed by the great flood, were transformed into fish.30 Perhaps their fish souls will be reborn again. Like the sun god who is born each morning after dying at night, the fish symbol with a [Page 60]shell in its body is on the sun’s back in figure 11, and intensifies the symbolism of rebirth after death. The sun glyph of this Maya god is on his head, which identifies him.31 We find the same thought in Egypt. The common bulti fish is associated with the sun because of its red color. Richard Wilkinson explains the symbolism of the bulti fish in Egypt: “[T]he spirit of the deceased was believed to rise from the waters of the afterlife as the sun had risen from the primeval lake.”32

Figure 11. Sun god with fish and shell on back. (Drawing by the author after Hellmuth, Monster und Menschen, 109.)

Between 1554 and 1558, a phonetic manuscript of the Popol Vuh was related to the Spanish by various members of the K’iche’ Maya lineage. In 1701, a Catholic monk named Francisco Ximenez, transcribed the Popol Vuh into Spanish from the K’iche’ language written down phonetically earlier.33 These mythological stories were considered a sacred narrative of the creation, with several episodes involving the Hero Twins, named Hunahpu and Xbalanque. There are many stela at Izapa that portray events described in the Popol Vuh. One could speculate the fish on Stela 5 represent the Hero Twins, since years later they are associated with fish. However, there are no stelae at Izapa showing the Hero Twins of the Popol Vuh as fish.

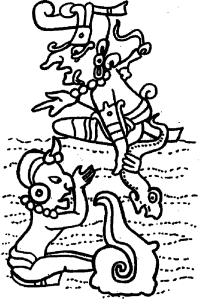

In figure 12,34 one of these accounts in the Popol Vuh of the Hero Twins is pictured on a Maya vase created hundreds of years before [Page 61]the K’iche’ Maya related their mythology to the Spanish. In this story told in the Popol Vuh, it was the intention of the Lords of Death in the underworld ballcourt of Xibalba, to kill the Hero Twins. However, the twins were exceedingly clever and knew of their design and devised a plan to trick the Lords of Death. The twins jumped into a fiery furnace. The Lords of Death threw their ashes into the underworld river, believing this was their demise. However, in a miraculous turn of events, the Hero Twins turned into “people-fish” and were subsequently reborn.35

Figure 12. Hero Twin and fish emerge from fish serpent-like monster on lower portion of a Maya vase, housed at the Popol Vuh Museum, Guatemala. (Drawing by the author after Reents-Budet, Painting the Maya Universe, 274.)

Researchers are in agreement that this story from the Popol Vuh is illustrated on the Maya vase (see figure 12). Above the figures in the water, a canoe travels through the Milky Way. Below the canoe is a young man, one of the Hero Twins, who comes face to face with a fish, both appearing to emerge from a larger fish/serpent-like creature. Dorie Reents-Budet suggests that one of the Popol Vuh Hero Twins has already been reborn, while the other appears as a fish before his metamorphosis or rebirth.36

Figure 13. Maya Hieroglyph unen, translated as “baby.”

Note that the Hero Twin is portrayed as a baby when delivered. A Maya logograph, unen, translates as “baby” (see figure 13). The Maya visualized this birthing position in several ways: as a newborn baby, a woman giving birth, or a deceased individual being reborn. The latter would apply to the Hero Twin in figure 12. The most famous portrayal of this position is on the sarcophagus lid of King K’inich Janaab Pakal [Page 62]in Palenque, Chiapas, Mexico (see figure 14). The deceased is transformed into the divine Maize god, who resurrects with the World Tree rising from or behind him.37

Figure 14. Sarcophagus lid of Kinich Janaab Pakal, Palenque, Chiapas, Mexico. (Drawing by Tom Weller. Permission granted for use of this illustration.)

Another incident of fish and man may be significant at El Tajin, Veracruz. A stone called Panel 5 in the South Ballcourt depicts a man sitting in a temple over the waters of the underworld. He has a fish attached to his head resembling a whole fish-helmet, leaving only the features of his face showing. Taube called him a “fish-man.” Above the temple on the roof sits a deity with a large solar panel over his abdomen.38 The “fish-man” will be reborn as is indicated by the symbols surrounding him. Deduced from their mythology, Taube proposed the “fish-man” probably represents a former race of fish-men that had a rebirth resulting in the creation of mankind.39

Figure 15. Fish over the deceased in Mimbres bowl. (Drawing by the author after photograph in Thompson, “Pre-Columbian Venus,” 175.)

Some Mesoamerican religious traditions influenced the American Southwest. For example, the Tewa, a linguistic Pueblo group, associated their ancestors with a lake of origin named patowa, translating as “fish-people.”40 In a Classic Mimbres bowl from the Pueblo Indians, the central figure is a man depicted in a birthing or hocker position, even though he was a male (see figure 1541). This position can also be seen in figure 5. The fish behind the man’s head in the Mimbres bowl indicates he is deceased.42 The stars above and below designate where his soul is destined to go in the heavens.

[Page 64]It should be noted there were many other interactions between the American Southwest and Mesoamerica.43 A web of Mesoamerican iconography exists among the southwest Indians, even to this day. For example, symbolism and goods were filtered into the southwest such as ballcourts, pyrite mirror, and copper bells.44 This was due to regional trade networks with Mesoamerica. Perhaps the most significant find were macaws (parrots) from Mexico and Central America, hundreds of miles away. The Hopi today have a Parrot Clan. Turquoise was one of the exchange items prized by Mesoamericans, as this bright colored stone was used for jewelry by high-ranking individuals and rulers. Therefore, the fish symbolism evident in figure 15 is appropriate.

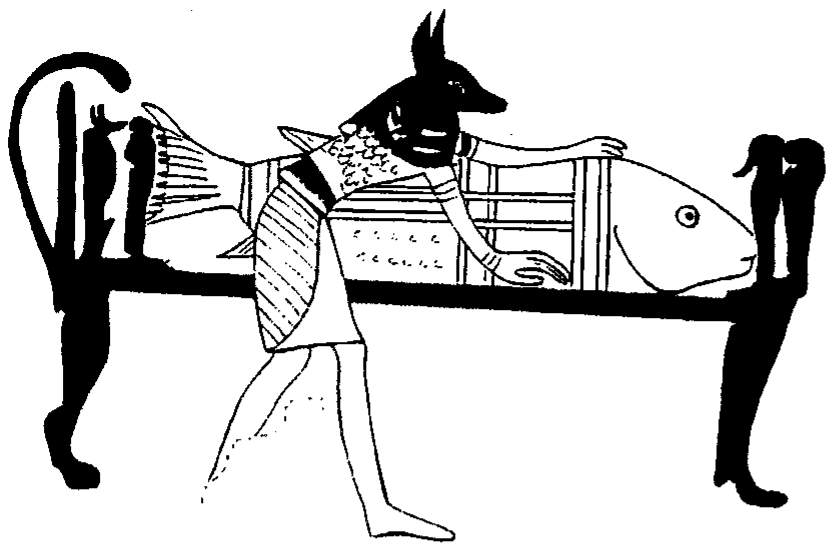

We see corresponding symbolism of the fish to death and rebirth in Egypt. The tomb mural at Deir el-Medinah, Thebes, depicts a fish in the process of being embalmed by Anubis (figure 16).45 Buffie Johnson postulates that the deceased, portrayed as a fish, should be considered as winding its way through the embryonic waters of the Underworld before its rebirth at dawn.46 It may be significant that the Egyptian hieroglyph for a man’s body or corpse contains a fish sign: XA is fish and XAy.t is the word for corpse47 (see figure 17). Considering [Page 65]the mural in Thebes with a bier having a fish, the word for body or corpse containing a fish, and the belief that the deceased swim symbolically in the waters as fish before their resurrection,48 This concept may parallel fish symbolism held by many people in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica.

Figure 16. Fish as mummy, Thebes, Deir el-Medinah, Tomb of Kha’bekhet #2, (Drawing by the author after photograph from Wikimedia Commons.)

Egyptian Connection and Joseph’s Sons

Figure 17. Egyptian hieroglyph for “body” or “corpse.”

We know the Book of Mormon was written in what the prophet Mormon called Reformed Egyptian (Mormon 9:32). It is certain they knew how to read Egyptian, inasmuch as the brass plates formerly held by Laban were written in Egyptian (Mosiah 1:3–4). Even before Nephi obtained the brass plates, he wrote, “And behold, it is wisdom in [Page 66]God that we should obtain these records, that we may preserve unto our children the language of our fathers” (1 Nephi 3:19). Their knowledge of Egyptian writing may be the result of Lehi’s family travelling to Egypt, or perhaps learning it from merchants visiting from Egypt, or another reason that was not explained in the Book of Mormon. This is not to say that fish traditions were known as a result of Lehi’s family understanding Egyptian, but it does remain a possibility. Can you learn a foreign country’s language without knowing some of their traditions? Whether it is a valid point for Lehi’s family being familiar with Egyptian traditions, it is an interesting supposition to note the symbol of a fish in Egyptian may sometimes have a nearly identical meaning of some fish in Mesoamerican artistic expressions.

A verse in Habakkuk 1:14 refers to men and fish, and reads that the Lord “makes men as fish of the sea.” Edward Bleiberg, curator for the Brooklyn Museum, expressed that fish not only symbolized fertility and birth, but carving a fish on a gravestone represented the hope for rebirth in the next life50 (see figure 1851). There is evidence the fish is symbolically related to a people in Israel, particularly the lineage of Joseph’s sons, Ephraim and Manasseh. The Encyclopedia of Jewish Symbols explains this concept.52 While in Egypt, Jacob blessed Joseph’s two sons, Ephraim and Manasseh, when he said, “Let them multiply in the midst of the earth.” In Hebrew, the word multiply is yidgu and is derived from fish, dägim. Jewish rabbis believe this is deduced from the fact that their progeny would multiply like fertile fish and be protected as the sea protects this species. Ephraim and Manasseh, therefore, have as a symbol—the fish.

Figure 18. Example of tombstone with fish in the Old Jewish Cemetery in Prague, Czech Republic. (Photograph from Wikimedia Commons.)

Years after the blessing of Ephraim and Manasseh by Jacob, King Manasseh built one of Jerusalem’s main entrances called the Fish Gate (2 Chronicles 33:14). Zephaniah prophesied a cry would come from the Fish Gate at the end of times (Zephaniah 1:10), which is apparently a type of the Second Coming. Many Jewish homes have murals containing fish, and Louis Ginzberg discusses standards carried by [Page 67]each of the tribes of Israel, designating their colors, inscriptions, and figures worked on each of them. On Ephraim’s standard, Ginzberg commented this particular standard was styled in the form of a fish.53 Ishmael’s family in the Book of Mormon was invited by Lehi to join with their group to flee from Jerusalem, which they accepted (1 Nephi 7). The daughters of Ishmael married Lehi’s sons. Lehi’s forefathers were of the lineage of Manasseh and Ishmael’s family the lineage of Ephraim.54 Consequently, both lines are associated with the sign of the fish.

As has been demonstrated, fish are associated with Ephraim and Manasseh, which is a much stronger connection on Stela 5, Izapa, than the fish of the Popol Vuh. Of the twelve tribes in Israel, Joseph is the one selected for his descendants to belong to the lineages associated with the fish.

Lehi and Sariah were of the tribe of Manasseh, and they are in a direct line of the fish hanging on the celestial band of Stela 5, Izapa, representing their rebirth/resurrection and immortality. The evidence presented here is not just speculation, but a very strong possibility that Stela 5, Izapa, is a distant remembrance of Lehi’s dream of the Tree of Life. Keith H. Meservy wrote:

[Page 68]The distillation of a wise idea into a succinct, well-expressed form made it easy to remember; if it were easier to remember it would be easier to pass from one generation to another. And this was the intent—to pass wisdom from the parent to the child.55

Go here to see the 3 thoughts on ““Birth and Rebirth: The Fish in Mesoamerican Art and Its Implication on Stela 5, Izapa, Chiapas, Mexico”” or to comment on it.