Abstract: In the weeks, months, and years following the murders of the Prophet Joseph Smith and his brother, Hyrum, several aspirants stepped forward to claim the mantle of the prophet. Who were these individuals with claims to the leadership of the church? What were their motives? How were these men able to inspire large numbers of saints to follow them? What became of their efforts and how are their works manifest in the present day? The reasons that members or prospective members chose or rejected the claims of these aspirants are examined, as are the churches of the organizations that were established by them. That study is augmented by a discussion of where these religious “expressions” subsequently gathered and the status of those entities today.

Those individuals even modestly familiar with the history of the Restoration are familiar with the immediate return of Sidney Rigdon to Nauvoo as soon as he received the news of the death of Joseph Smith and of Rigdon’s claim to be the Guardian of the church. Likewise, many church adherents are also familiar with Brigham Young’s return to Nauvoo from his mission in the Eastern States, arriving just in time for a subsequent showdown with Rigdon at a hastily arranged conference. Many of those in attendance at that historic 8 August 1844 conference believed they saw the image or heard the voice of Joseph Smith when Young spoke to the estimated 5,000 in attendance.1

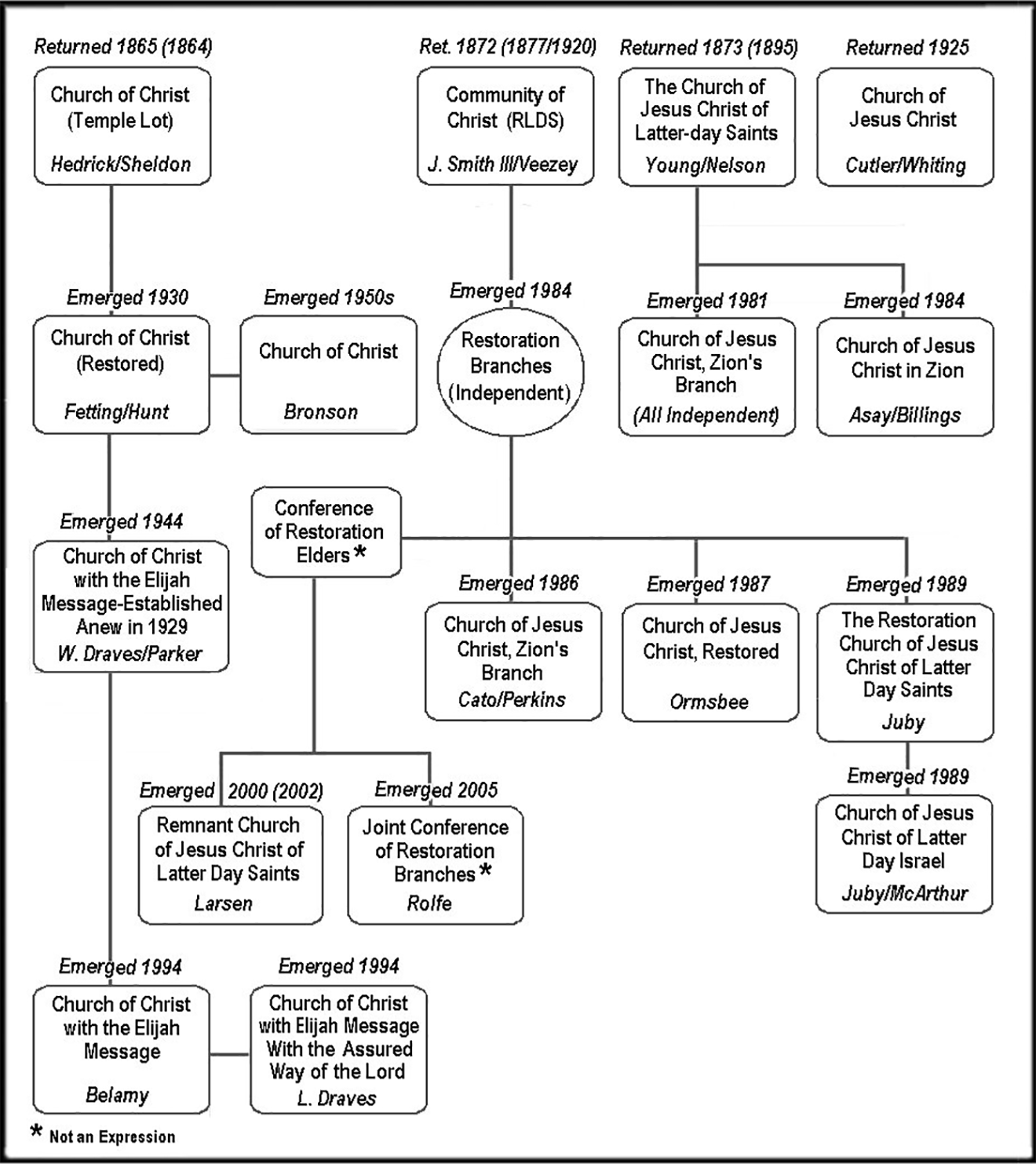

[Page 336]What is generally not known, however, is that: 1) in the aftermath of the martyrdom there were several individuals who claimed that they had been directed to take charge of what they now surmised was a leaderless church, or 2) as circumstances developed, they came to that conclusion. Subsequently, a considerable number of organized groups departed from the church that Joseph Smith originally organized. How extensive were those departures? Historian Steven L. Shields has tallied that, during the 194 years since the Church of Christ was founded at Fayette, New York, on 6 April 1830, approximately 500 separations from the original church have occurred. Furthermore, he has documented some 125 church organizations or associations functioning today that consider Joseph Smith the prophet of the Restoration.2

It is not possible to discuss all the organizations in a single article. We can, however, gain a better understanding of the aftermath of the martyrdom and the leadership issues that were faced by the saints. We can also gain some understanding of who the aspirants to the mantle of Joseph Smith were and what motivated them to pursue their quest to lead what they now perceived as a leaderless flock. To facilitate that understanding, I will present a brief sketch of the influential leaders who were either aspirants who sought the mantle or promoted others to seek that mantle.

To avoid sensitivities with terms like off-shoots, splinter groups, and schisms, I use the word expression to refer to the separate organizations or associations that emanated from the original church. Most expressions either consider themselves the original church, or that their expression has been reconstituted or divinely separated. Each individual or aspirant and the expression associated with that person is listed below in table 1. Note, again, that the list is necessarily incomplete for this relatively short treatment of the topic.

This paper is organized in two parts. Part One details doctrinal and policy similarities and differences across the various expressions of the Restoration. Part Two provides timelines and brief biographies of selected aspirants who claimed leadership of the church.

[Page 337]Table 1. Major aspirants and expressions.

| Aspirants | Name(s) of Expressions3 | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Brigham Young and the Quorum of the Twelve | The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints | 1844 |

| Sidney Rigdon | Church of Christ; Church of Jesus Christ of the Children of Zion (second attempt) |

1845 1863 |

| James J. Strang | Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints | 1844 |

| Lyman Wight | Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (Merged with William Smith 1849; dissolved 1851) |

1849 1851 |

| William Smith | Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints | 1847 |

| Granville Hedrick | Church of Christ | 1852 |

| Jason W. Briggs and Zenos H. Gurley, Sr. |

New Organization4 (Reorganized) Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints5 |

1852 1860 |

| Alpheus Cutler | Church of Jesus Christ | 1853 |

| Joseph Smith III | (Reorganized) Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints | 1860 |

| William Bickerton | Church of Jesus Christ | 1852 |

Part One: Doctrinal Issues

Before discussing the motivations of the aspirants who announced themselves as successors to the mantle of the Prophet Joseph Smith in the months and years following his death at Carthage, it will be [Page 338]helpful to understand the varying doctrines and beliefs of these individuals and the expressions of the Restoration that they led. Of necessity, sometimes aspirants mentioned in Part One will not be formally presented until later in the paper. In the following discussion, references to the Doctrine and Covenants or D&C will refer to the volume as printed by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, while the version printed by the Community of Christ will be referred to as the RLDS D&C.6

Further, following the conventions of the Interpreter journal, references to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or its members will not be abbreviated with the term LDS. RLDS, nevertheless, may be used. Additionally, the Church Style Guide calls for the word church to be capitalized. However, since this paper deals with the early church and other expressions of the church, the discussion will deviate from the recommended style of capitalizing that word.

Elements that are similar across the expressions

It is obvious that those who separated from the original church established by Joseph Smith had differing views on doctrine and policy. That is to be expected. Despite these differences, there are several points of similarity or near-similarity. Before discussing the differences, I will briefly mention the points on which there was some agreement.

The origins and names of the expressions

All of the expressions examined in this essay claim Joseph Smith Jr. as their founder. None claimed or claim to be creating and/or restoring a church without the foundation of Joseph Smith, at least in his earlier years. That is an important base on which to begin the discussion.

The name of the original 1830 church was the Church of Christ (D&C 21:3; RLDS D&C 19:1c). In 1834, that title was changed to the Church of the Latter Day Saints.7 A revelation given to Joseph Smith on 26 April 1838 (D&C 115:3–4) formalized the name of the church to The Church [Page 339]of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Consequently, nearly all of the expressions maintain that name or some variation of it. Delegates to the World Conference of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints voted on 7 April 2000 to change the name of this expression of the Restoration to Community of Christ.8

The use of the identifier “Mormon” was taken, of course, from the Book of Mormon. The first edition of the book was available for purchase in Palmyra, New York, on 26 March 1830, shortly before the organization of the Church of Christ on 6 April 1830.9 The name initially used to describe followers or adherents to the religious organization introduced by Joseph Smith was “Mormonite.”10 The name was intended as a derogatory identifier, but members soon began referring to themselves with that name. The use of that identifier was short-lived, the “ite” being dropped, and the name “Mormon” was generally used thereafter to designate followers of Joseph Smith. Within the church, regarding the source of that name (i.e., the Book of Mormon), Joseph Smith, speaking to a meeting of the Quorum of the Twelve in 1841, stated emphatically that “the Book of Mormon is . . . the keystone of our religion.”11 The identifier “Mormon” is also quite common across the various expressions and is often applied in both speech and print by outsiders, though not favored by most members of the various expressions.

[Page 340]Published revelations of Joseph Smith

A significant majority of today’s expressions assert the historicity of the Book of Mormon and acknowledge the volume as scripture. However, the Community of Christ accommodates a range of individual perspectives regarding the role and authenticity of that book.12

Additionally, a preponderance of these expressions accept Joseph Smith’s published revelations as the inspired word of the Lord. These divine disclosures were originally selected to be printed in A Book of Commandments for the Government of the Church of Christ. It was to have been published by William W. Phelps at Independence, Missouri, 1832–33.13 Phelps had been called in 1831 by revelation to “be planted in this place [Independence], and be established as a printer unto the church” (D&C 57:11; RLDS D&C 57:5a). The volume, which was intended to be small, was never completed because of mob action in Jackson County in mid-summer of 1833. A populace of local angry residents pillaged the printing office and residence of Phelps on 20 July 1833 and attempted to destroy the printed signatures (sheets). Fortunately, some of the signatures that had been removed from the printing shop by the mob and scattered were later gathered up, cut, and bound into an unknown number of small volumes.14

After the 1833 Missouri events, a renewed effort to print Smith’s revelations commenced in Kirtland, Ohio. He edited his revelations received up to mid-1833 and added some additional revelations he received up to the date of publication.15 The result was the 1835 Doctrine and Covenants of the Church of the Latter Day Saints: Carefully Selected From The Revelations of God.

An 1844 edition of the Doctrine and Covenants was published shortly after Smith’s death and contained eight additional revelations. [Page 341]Thereafter, some previously omitted revelations given to Smith were published in editions of the Doctrine and Covenants by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,16 the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (Community of Christ),17 and others. There are also differences in the subsequent publications of Smith’s revelations by various expressions. Some expressions only accept Smith’s revelations up to a specific month and year. Many of them also include in their Doctrine and Covenants (or a re-named volume) additional sections considered as revelations given to their prophets, apostles, or others within their churches. Indeed, there is a wide range of what is considered “revelatory” within the spectrum of the various expressions. Examples from expressions featured in this article include:

- Church of Christ (Temple Lot): Any member of the Council of Twelve Apostles may receive a revelation for the church; however, the revelation must be submitted to the church for a confirmation or rejection vote.18

- The Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (Community of Christ): does not include the Joseph Smith Jr. revelations after 1838 in their published [Page 342]Doctrine and Covenants.19 Currently, only the Prophet-President may receive revelations for the church. To canonize a revelation, it must be accepted by a majority vote of the official delegates at a World Conference.

- Church of Jesus Christ (Monongahela, PA): Any member of the church may receive a revelation for the church, but it must be subsequently sanctioned by a vote of the members of the church.20

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: Only the Prophet-President may receive revelations for the church. For a revelation to be canonized, it is presented to church members at a session of a General Conference. The revelation is then voted upon for acceptance as canonized scripture. Other leaders and individuals may receive revelation for their area of responsibility, family, or for themselves.21

Within other expressions, the prophet, president, presiding elder, or other church leader is entitled to a receive a church-wide revelation.

For ease of presentation, future mention of revelations, visions, and promptings accepted by the various expressions will be labeled as stated. There will be no attempt to question the validity of those claims.

Elements that vary among expressions

Despite the surface similarities, several points of doctrine constitute significant differences between the expressions. They include membership considerations, priesthood, the concept of a “gathering” for the redemption of Zion, and the question of the future construction of a Millennial Temple or temple complex.

Membership considerations

When an individual is converted and subsequently baptized, he or she becomes a member of that church. This person’s membership can be [Page 343]terminated at any time, either by the church or by the individual. If the termination is instigated by the church, an official will usually confront the person about his or her errant behavior or apostasy. If the member, instead, freely leaves the organization, it was often because they began to question either doctrine or leadership. In many cases, that original baptism will continue to be recognized by the new expression with whom the person later becomes associated.22

Priesthood and priesthood keys

The position taken by the majority of the expressions regarding priesthood authority is that its bestowal, and the accompanying ordination to any designated office therein, is an individually conferred blessing that is retained by that person so ordained, regardless of whether that individual is later separated from the original church.23 Examples from the early post-martyrdom period are those of Zenos H. Gurley Sr., William Marks, and Joseph Smith III. Smith assumed his “father’s place” as president and leader of the New Organization at the April 1860 conference held in Amboy, Illinois. Gurley, who became a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of the New Organization, and Marks, who had recently (1859) joined the New Organization and was now a member of the High Priests quorum,24 ordained Smith as President of the High Priesthood.25 Gurley and Smith III are discussed later in this paper.26

In the years following Joseph Smith’s death, certain early church apostles, no longer affiliated with the original church, conferred upon other men the Melchizedek Priesthood and ordained them to priesthood offices, including that of an apostle. Another example of this varying interpretation of priesthood authority involved John E. Page, a [Page 344]former member of the Twelve Apostles of the original church.27 After becoming a member of the Church of Christ in 1862, Page ordained Granville Hedrick an apostle on 17 May 1863. Two months later, on 19 July 1863, Page ordained Hedrick “Prophet, Seer, Revelator and Translator” of the church.28

The gathering and the redemption of Zion

Nearly all expressions support a “gathering” concept. This may or may not include a specific geographical location, and that location may or may not be permanent. One week following the Kirtland Temple dedication in April 1836, Moses appeared to Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdrey and restored the “keys of the gathering of Israel from the four parts of the earth” (D&C 110:11). Since the revelatory gathering “call to the Ohio” in 1830–31 (D&C 37:3, 38:31–33, 39:14; RLDS D&C 37:2a, 38a-c, 39:4d) and the subsequent directive in 1831 to gather to Missouri (D&C 45:64–66, 52:2, 57:1; RLDS D&C 45:12a-c, 52:1b, 57:1a), members of the original church, in compliance to revelations given to Joseph, uprooted themselves and moved as directed.29 In compliance, many early adherents moved westward from Ohio to Jackson County, Missouri.30 Many of these early members dealt with additional re-locations or gatherings in Missouri during the 1830s. Likewise, members living in and around Kirtland, of necessity, departed for Far West, Missouri, in 1838. The October 1838 Extermination Order of Governor Lilburn W. Boggs forced the saints to flee the State of [Page 345]Missouri.31 They turned to the east and gathered in western Illinois, primarily in and around the town of Quincy.32

In late April 1839, a conference of the church was held at Quincy, where the Prophet, Bishop Vinson Knight, and Alanson Ripley were appointed to select a relocation site. Gathering sites in Hancock County, Illinois, and Lee County, Iowa, were selected. By summer 1839, the small town of Commerce was promoted as the “main gathering place,” and Commerce was soon renamed Nauvoo.33 And, of course, there was the gathering to the Great Basin of the American West led by Brigham Young in 1847.34

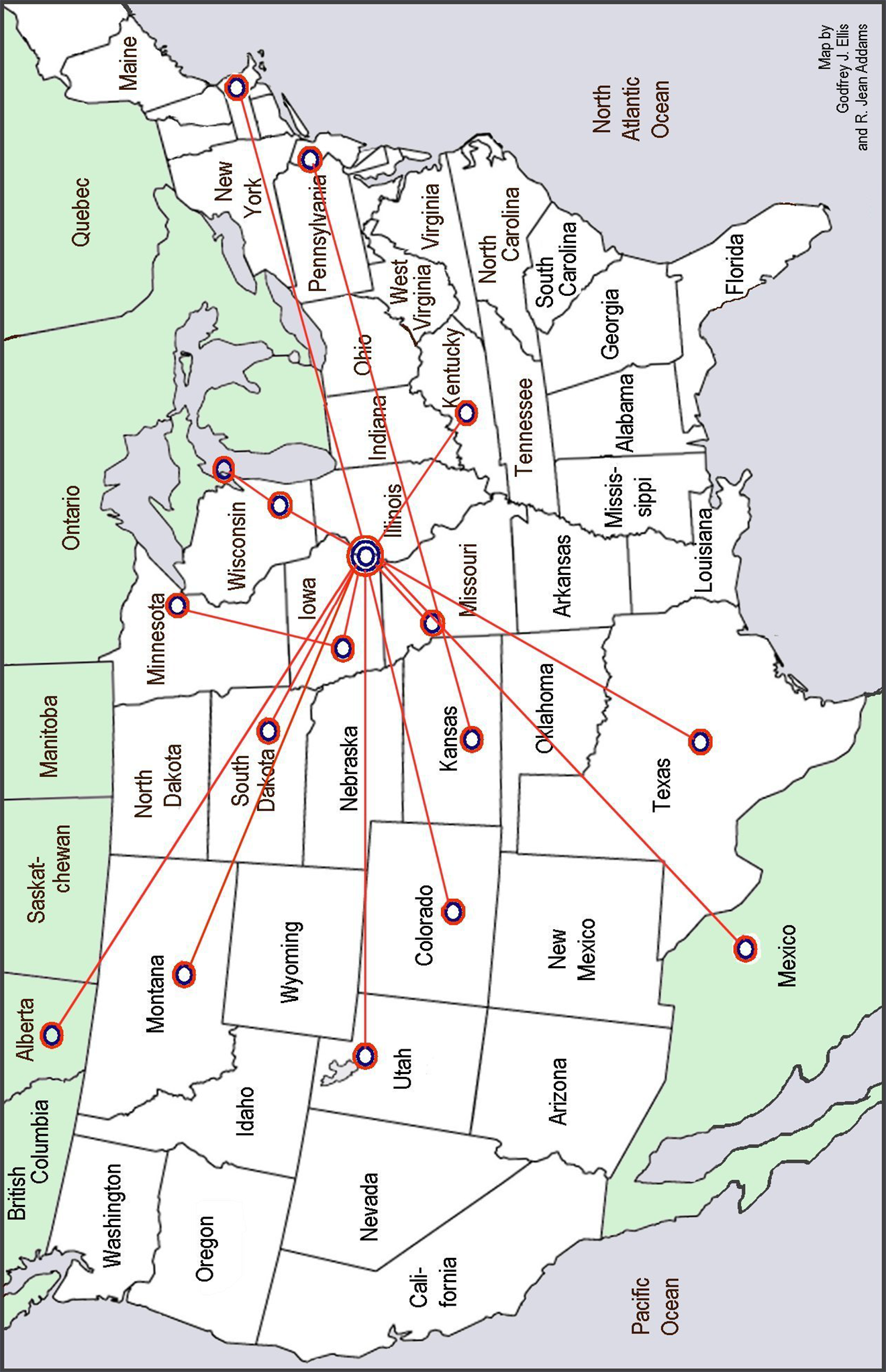

Other early gathering locations by the various expressions have included Pennsylvania, Iowa, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Kansas. Later subsequent gatherings by certain expressions have included locations in Montana, Arizona, Colorado, Texas, South Dakota, southern Alberta, southern Manitoba, and northern Mexico. Figure 1 shows the geographical location of many of the expressions.

In September 1830, only five months after the church was organized, Smith received a revelation enjoining the members of the church to “bring to pass the gathering of the Lord’s elect” (D&C 29:7–8; RLDS D&C 28:2.c). In the summer of 1831, Joseph Smith and several others traveled to western Missouri in fulfillment of the Lord’s directive.35

Arriving in Independence in mid-July 1831, additional information was revealed to Smith regarding the location for a Millennial Temple (D&C 57; RLDS D&C 57). Jones Flournoy, postmaster of Independence and early settler, was the original claimant who had first rights (squatters rights) to the property. He granted partial access to Smith. With revelatory specifics, Smith and others made arrangements for the area where the Lord had directed Smith to locate the temple.36 On 3 August 1831, Joseph Smith, Oliver Cowdery, Sidney Rigdon, Martin Harris, and several of the brethren gathered to witness and participate in the historic event.37

Figure 1. Locations of some of the early expressions of the Restoration.

[Page 347]Smith, in a simple ceremony, dedicated the spot where the Millennial Temple would one day stand.38 As part of the ceremony, a stone was placed on the northeast corner of the planned edifice.39 The “Temple Lot Property” (63.27 acres) was subsequently purchased by Bishop Edward Partridge on 19 December 1831.40

Most of the expressions, therefore, believe that the Millennial Temple will be built on the Temple Lot Property. It is in Independence that Smith, nearly two years later, expanded his vision of Zion and designated a significant increase in the size of the original spot for a temple. In fact, Smith’s drawing details a cluster of twenty-four temples where the Lord will return in the Last Days for his millennial reign.41

The Redemption of Zion, however, is much more than a gathering. More specifically, most of the expressions believe that in fulfillment of the scriptures regarding the Redemption of Zion, i.e., that the Millennial Temple will be built on the 1831 dedicated lot in Independence. Furthermore, they adhere to the tenet that this is the location of the future city of Zion or the New Jerusalem. The Church of Jesus Christ (Monongahela, PA) believes that a “New Jerusalem” will be located “somewhere in the Americas,” but not necessarily in Jackson County.42

Based on their understanding of the revelations given to Joseph Smith, several of the expressions of the Restoration have already acted on this belief, i.e., they have reestablished a physical presence [Page 348]in Jackson County. The Church of Christ moved to Independence in 1867, centered upon a revelation that Granville Hedrick received in 1864.43 The majority of its members also physically relocated to the Independence area in February 1867, as admonished in that revelation.44 The Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints authorized its members to return to Jackson County and thus reestablish a physical presence in 1877.45 This initial authorization was subsequently and significantly upgraded when the church officially moved its headquarters to Independence in 1920.46 In 1900, the Utah-based Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints moved its mission office from St. John, Kansas, to Kansas City, Missouri, to officially reestablish the church’s return to Jackson County, although there were several families already living in the greater community. In 1907, the church relocated the Central States Mission Office to Independence where a mission headquarters has been maintained since that time.47 The Church of Jesus Christ (Cutler) moved its own headquarters from Minnesota to Independence in 1928.48 Other separations from these [Page 349]four expressions have also established a presence in Independence in the years since 1928.49 More information, not essential to the thesis of this paper, is located in the Appendix for interested readers.

In the years following (between 1867 and 1900), the Church of Christ, the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints committed to the reacquisition of land in the Independence area. Each expression began to acquire (or re-acquire) Temple Lot Property originally purchased by Bishop Edward Partridge for the church in December 1831 as opportunities and finances were available.50

As noted previously, the earliest returning expression to Independence was the Church of Christ. They acquired 2.5 acres of the original Temple Lot Property in 1867–74.51 In 1906, the City of Independence sold the church a small triangular strip of land (approximately one-fourth acre).52 This acquisition brought their ownership to a total of 2.75 acres. Their current church building, including a chapel, classrooms, and offices for local and world headquarters, was constructed on a portion of this acreage and was dedicated in 1992 following a fire set by an arsonist on 1 January 1990, which destroyed the previous building on this same site.53

[Page 350]At present, the Community of Christ is the largest landowner on the dedicated Temple Lot Property, having acquired 40.5 acres over many years.54 The church built their Auditorium on a large piece of their property and dedicated that building in 1962.55 A temple was constructed on a portion of their acreage and dedicated in 1994, although the church does not connect the temple with “millennial expectations.”56 The temple and The Auditorium both house administrative offices for their world headquarters. Additionally, a sanctuary, library, and archives are located in the temple.

A majority of the expressions believe that the Millennial Temple will be built on the Temple Lot Property purchased by Bishop Partridge, as originally directed by revelation in July 1831.57 Both the Church of Christ and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints subscribe to the specific language of Smith’s revelation, that is, that the Millennial Temple will be built on the dedicated “spot for the temple” located about a mile west of the courthouse in Independence (D&C 57:3).58 The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints secured 20 acres of the original Temple Lot Property in 1904.59 The Visitors Center was [Page 351]constructed on a portion of that land and was dedicated in 1971.60 The church also constructed a large stake center adjacent to the property. Combined, these three expressions now own the 63.27 acres originally purchased by Bishop Partridge for the express purpose of building the Millennial Temple as envisioned by Joseph Smith.61 The Church of Jesus Christ (Cutlerite) acquired property to the immediate south of the Temple Lot Property in 1924. The building occupied by the church today was constructed in 1928.62

As of 2024, the total membership of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is slightly over 17 million,63 the Community of Christ has 248,500 members,64 the Church of Jesus Christ (Monongahela, PA) has 23,000 members,65 and the Church of Christ (Temple Lot) has 12,000 to 15,000 members.66 All other expressions have 10,000 or fewer members.

[Page 352]Elements influencing the following or rejection of an aspirant

Besides understanding the concepts of membership, priesthood, and the gathering of Zion, there were several reasons why members left the original church following the martyrdom and chose to follow (or reject) one of the claimants in the post-martyrdom period. Five major considerations will now be discussed.

Authority issues with leaders

The aspirants to Joseph Smith’s position each presented a different position of why and/or how they had the authority to lead the church in the post-martyrdom era. They were:

- Brigham Young: revelation and ordination as president of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles and the “Last Charge” directive of Joseph Smith

- Sidney Rigdon: First Counselor in the First Presidency and vice-presidential running mate at the time of the Martyrdom

- James J. Strang: letter from Joseph Smith authorizing the authority and a confirming manifestation

- William Smith: right by lineage

- Joseph Smith III: three blessings from his father confirming his succession to his father’s position in the First Presidency

Many people were convinced by one or more of these justifications. Other individuals were repelled.

The concept of a “rejected gospel/church”

A belief that the Lord had “rejected” the church was raised by some individuals in the post-martyrdom period and used as a justification of why a new direction or reorganization of the church was necessary. This reasoning was based upon the 19 January 1841 revelation given to Joseph Smith at Nauvoo (D&C 124:25–32; RLDS D&C 107:10–11). The revelation covered a variety of topics pertinent to the church at that time, including the command to build a temple. In this revelation the Lord stated, “I command you, all ye my saints, to build a house unto me; and I grant unto you a sufficient time to build a house unto me . . . and if you do not these things at the end of the appointment ye shall be rejected as a church, with your dead, saith the Lord your God” (D&C 124:32; RLDS D&C 107:11a).

Since the temple was still under construction at the time of Joseph Smith’s death, some individuals used the language of this revelation as [Page 353]the basis of the “rejected church” argument. This argument reached a high point in the 1890s with the 1894 publication of Succession in the Presidency of the Church by Latter-day Saint historian B. H. Roberts.67 His position held that the temple was sufficiently completed to facilitate the promised endowment in which members participated before vacating Nauvoo.68 This explanation was countered by Heman C. Smith of the RLDS Church with his 1898 rebuttal publication of True Succession in Church Presidency.69

Baptism for the dead

Joseph Smith introduced certain key ideas during the Nauvoo period (1839–44), specifically, actions for deceased ancestors such as temple ordinances (baptism for the dead and the endowment). The following brief paragraphs outline the positions taken by various early expressions vis-à-vis these practices and doctrines. Again, I note that while the names of various aspirants of these competing expressions will be mentioned, for the sake of presentation, these men will not be fully introduced until Part Two of this paper.

While some readers might assume that such practices and doctrines originated in later years, more and more scholarship is demonstrating that many, if not most, of the so-called “Nauvoo-era doctrines” were actually a part of the Restoration from the very beginning. Current research is showing that such doctrines were clarified and re-emphasized in Nauvoo. As an example, a recent article by Andrew Miller demonstrates strong similarities between the modern church endowment and the discourse of King Benjamin as recorded in the book of Mosiah.70 He also offers a literature review of other scholars finding the same thing. Jeffrey Bradshaw similarly finds evidence for early doctrine occurring in the Book of Moses.71 This body of research [Page 354]suggests that these ideas predate the Nauvoo period by twenty or more years. Similarly, Larsen and Wright demonstrate that the concept of theosis or divinization occurs throughout the Book of Mormon.72

The idea of living mortals focusing on the spiritual well-being of their deceased ancestors began at essentially the same time as the First Vision. Three years and five months later, during four appearances of Moroni, Joseph was told that “God had a work for [him] to do” in which “the hearts of the children shall turn to their fathers” (Joseph Smith—History 1:33, 39). For Joseph, one of the ways to accomplish this divine mission was through the practice of vicarious baptism for ancestors who had passed on. The ordinance of baptism for the dead was first specifically discussed by Smith on 15 August 1840 while delivering a sermon at the funeral of Seymour Brunson.73 The ordinance of baptizing “for and in behalf of someone who is dead” was practiced in Nauvoo beginning in September 1841, with baptisms performed in the Mississippi River.74 In January 1841, a revelation to the Prophet Joseph provided additional insight on this subject (D&C 124:28–42), including placing the ordinance in the context of restored knowledge.

Baptism for the dead was continued by several expressions in the years following the prophet’s death and is a fundamental tenet of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints today. However, the expressions that developed in the years following the martyrdom have varied in their acceptance of these ordinances. Although certain of these ordinances were continued by some of the new expressions, in general these doctrinal practices were abandoned by most of the expressions that developed in the post-martyrdom era.

Following the Nauvoo exodus, baptism for the dead was not practiced again until 1867 by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. There are only three known documented exceptions to this pause in performing baptisms for the dead. The first exception

occurred on 4 April 1848. While in Iowa, just prior to his return trip to the Salt Lake Valley, Wilford Woodruff performed nine [Page 355]baptisms for deceased persons in the Missouri River, followed by four confirmations.75

The second exception occurred on 21 August 1855, with a baptism and confirmation “in City Creek in Salt Lake City.”76 The third occurred on 23 October 1857, when “two baptisms took place in the baptismal font affixed to the Endowment House in Salt Lake City.”77

Initially, and perhaps reluctantly, the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints continued to acknowledge the practice of baptism for the dead as “possibly legitimate.” Five years after Joseph Smith III was acknowledged as the prophet and president of the church, however, he expressed his concern regarding this specific doctrine and addressed the subject in a May 1865 council meeting with other leaders of the church. The council, in a carefully worded statement, resolved “that it is proper to teach the doctrine of baptism for the dead when it is necessary to do so in order to show the completeness of the plan of salvation, but wisdom dictates that the way should be prepared by the preaching of the first principles.”78 There was a stipulation, however, “that baptisms for the dead had to be carried out in a temple and with no prospect for the building of such an edifice in the immediate future, the doctrine was shunted into a nether land between belief and practice.”79 Historian Roger D. Launius concluded his remarks on this and other related subjects in his book Joseph Smith III: Pragmatic Prophet with a quote from Alma R. Blair who stated that “to ignore was to reject.”80

James Strang continued the practice of performing baptisms for [Page 356]the dead within his organization. One such example is documented in the Chronicles of Voree.81 Historian Vickie Speek points out that when Strang returned to Voree in August 1849 to preside over a church conference, “members of the Order of Enoch performed baptisms for their dead ancestors.”82

Alpheus Cutler also continued the ordinances of the Nauvoo era, including baptism for the dead. Historian Biloine Whiting Young quotes from an undated letter written by Jennie Whiting to her daughter Bonnie that when Bonnie’s sister Daisy died in 1906: “We sent for Uncle Lute and Uncle Vet who came and prayed for her and anointed her. . . . I was baptized for her and she is now resting in Paradise until the resurrection.” In her letter she added that during the time that Whiting was president, they “were permitted to work for the dead,” and commented, “We had several of these baptismal meetings.”83

From the examples listed above, it is clear that the practice of baptism for the dead was continued by some of the expressions in the post-martyrdom period. However, from the lack or absence of historical documentation for the majority of the expressions that developed in the years after Smith’s demise, it is apparent that the continuation of this ordinance was extremely limited. And, as also noted, the practice or ordinance of baptism for the dead, in concept, was initially acknowledged by the RLDS Church in 1865 but was soon set aside.

Endowment (temple ordinances)

Joseph Smith first introduced the ordinance of the endowment to a select group of trusted men on 4 May 1842.84 This event took place on the second story of his Red Brick Store in Nauvoo. Later, men and women received the endowment under Smith’s direction prior to his [Page 357]death in 1844.85 Thereafter, this ordinance was performed under the direction of the Quorum of the Twelve in the Nauvoo Temple.

As the political situation in Illinois became more acute for the church, plans were expedited for implementing their westward journey. Coupled with the departure to the Great Basin, a priority for Brigham Young was the completion of the temple. Obtaining one’s individual endowment in the temple, prior to the planned exodus, became a major concern. Although the temple was not completely finished, as rooms became functional, they were dedicated and put in use to accommodate church members wanting their endowment.86 Beginning in December 1845 and continuing until 7 February 1846, when the final ordinances were performed (as the first pioneer companies headed west), some 5,615 individuals had been endowed. These ordinances for the living continued in Utah Territory and were accomplished in temporary dedicated locations (for example, the Endowment House on Temple Square in Salt Lake City) until temples were completed. The first temple in Utah was built in St. George (1877), followed by Logan (1884), Manti (1888), and Salt Lake City (1893).87

Referring to the endowment, Joseph Smith III remarked some twenty years after the death of his father, “I cannot see anything sacred or divine in it.”88 He was never “seriously challenged in his denunciations of the practice of temple endowments” because the temple rituals were associated with the Utah church.89 That association ensured continuing opposition from RLDS membership.90

James Strang had undoubtedly heard about the sacred rites performed by Joseph Smith in his Red Brick Store over three years before the dedication of the Nauvoo Temple. In an attempt to bind his most loyal followers to his leadership and provide an opportunity for adherents to participate in a secret society, Strang introduced similar rituals. He established the Halcyon Order of the Illuminati for select church [Page 358]members. The first meeting of this order was 6 July 1846, two years after the martyrdom. The participants were initiated with secret handshakes, signs, and code words. The ceremony concluded with each participant swearing an oath to “never reveal” any of the secrets of the order. Strang also had plans in 1849 to build a temple near Voree.91

Lyman Wight also perceived a need to receive the endowment, as evidenced in his priority to build a temple soon after his followers settled in Zodiac, Texas. This facility was completed in 1849; reference is made to its completion in a revelation to William Smith as recorded in the minutes of his April 1850 conference when Smith and Wight were in a period of merging their respective churches.92

Alpheus Cutler, based on his memory of the ordinances, pledges, and oaths, also continued the Nauvoo Temple ordinances in his expression. His followers continued practicing temple rituals for thirty or more years following his death in 1864. In the 1890s, however, it appears that the rituals “had been allowed to lapse.” Under the leadership of Isaac Whiting, beginning in 1909, the Nauvoo Temple rituals were reinstated. When the church moved its headquarters from Clitherall, Minnesota, to Independence, Missouri, in 1928, they purchased property and built a church to the south of the Temple Lot Property. The second floor of their church was designated for the performance of Nauvoo Temple ordinances.93

Polygamy/plural marriage/celestial marriage/spiritual wives

Perhaps the most significant reason for following or rejecting the leadership of Joseph Smith and, later, Brigham Young and the Quorum of the Twelve, was the controversial teaching generally referred to as polygamy and technically called polygyny.94 It was also called plural marriage, spiritual wife doctrine, or celestial marriage.95 This doctrine [Page 359]was a major factor or turning point for followers of James Strang and William Smith, who vacillated on the acceptance or rejection of this highly volatile tenet.

This new doctrine, when first revealed by Joseph Smith to select individuals in 1841–42, was explained as only one of several parts of the “restoration of the ancient order of things in the dispensation of the fulness of times” and was only taught privately by Smith with a pledge to keep the disclosure confidential.96 As the circle of those to whom this teaching had been conveyed expanded during the two years prior to Smith’s death, rumors and innuendos regarding this marital arrangement began to circulate in Nauvoo.97

For William Law—a former counselor in the First Presidency and now a leader of a rival group, the True Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints—the doctrine of plural marriage was the proverbial last straw. It became the final motivating factor in his efforts to expose Smith as a fallen prophet. In May 1844, under the direction of Law and others, a printing press was purchased for the publication of a newspaper meant to “expose” Smith—The Nauvoo Expositor.98 The subsequent destruction of the newspaper, after its first and only issue on 7 June 1844, by order of the City Council and signed by Mayor Joseph Smith, was the primary cause of Smith’s imprisonment and death at Carthage on 27 June 1844.99

The acceptance or rejection of plural marriage became pivotal for many church members in deciding whom to follow in the period of 1844–60. As knowledge of this new and controversial doctrine expanded, there were other voices clamoring for support as to why they should lead the church. Both Sidney Rigdon and James Strang [Page 360]used this teaching as an added argument in their individual efforts to convince potential adherents to follow them. Rigdon referred to the purported precept as a “heretical practice” and “barbaric.”100 Strang stated that “spiritual wifery [was] an abomination.”101

Certainly by 1852, other individuals, unpersuaded by the claims of Rigdon or Strang, were using the issue of plural marriage as a reason for joining with them and their organizations versus staying with the leadership of Brigham Young. Jason Briggs, Zenos Gurley, and Granville Hedrick, for example, became disillusioned over the issue of plural marriage. Eight years after the martyrdom, they were still very much resistant to reestablishing any connection with Young. Briggs and Gurley were, individually, persuaded to first join up with Strang in the late 1840s.102 Upon learning that Strang had switched from opposition to acceptance of plural marriage, they left his organization in 1850. This same scenario was repeated as they next joined William Smith’s fledgling church, only to be disillusioned, again, when they discovered his involvement with polygamy in 1851.

Hedrick and his Crow Creek branch of the original church were appalled upon hearing of the August 1852 pronouncement made by Orson Pratt in Salt Lake City regarding the open advocacy of plural marriage.103 The Crow Creek branch immediately announced a “withdrawal from fellowship with all who were indulging in these evils.”104

One of the first pronouncements made by Joseph Smith III, on 6 April 1860, immediately prior to his being voted as the “prophet and president of the church” was his position on the subject of polygamy, which he referred to as an “utter abhorrence.”105 Thus, the acceptance [Page 361]or rejection of plural marriage became a serious decision-making factor for some members considering one or another of the contenders for the leadership of the church. This became even more of an issue as knowledge of the teaching became more widespread. Table 2 summarizes this acceptance or rejection of plural marriage.

Table 2. Response to plural marriage among the expressions.

| Expression | Leader | Accept/Reject |

|---|---|---|

| The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints | Young (the Twelve) | accept106 |

| Church of Christ | Rigdon | reject107 |

| Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints | Strang | reject/accept108 |

| Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints | William Smith | accept/reject/accept/reject |

| Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints | Wight | accept109 |

| Church of Christ (Temple Lot) | Hedrick | reject110 |

| Church of Jesus Christ | Cutler | accept/reject111 |

| Community of Christ (Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of LDS) | Briggs, Gurley, et. al./Joseph Smith III | reject112/reject113 |

| Church of Jesus Christ | Bickerton | reject114 |

[Page 362]Polygamy, indeed, would continue to be a “breaking point” for many members of the original church. The acceptance of this teaching also posed a serious consideration for prospective new members, as a result of increased missionary efforts of the Young-led church in Europe. Likewise, proselyting efforts of the New Organization/RLDS Church, James Strang, William Smith, Alpheus Cutler, and others brought significant challenges as they, out of necessity, were required to explain how and why they were different from the Utah-based church. In addition, there was a nationwide negative reaction to the practice. In 1856, John C. Fremont, a Republican party nominee for President of the United States, pledged to fight the “twin relics of barbarism” namely, slavery and polygamy.115 The subject of polygamy and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints would continue as a topic of national discussion for the next half-century.116

Part Two: Aspirants and Expressions

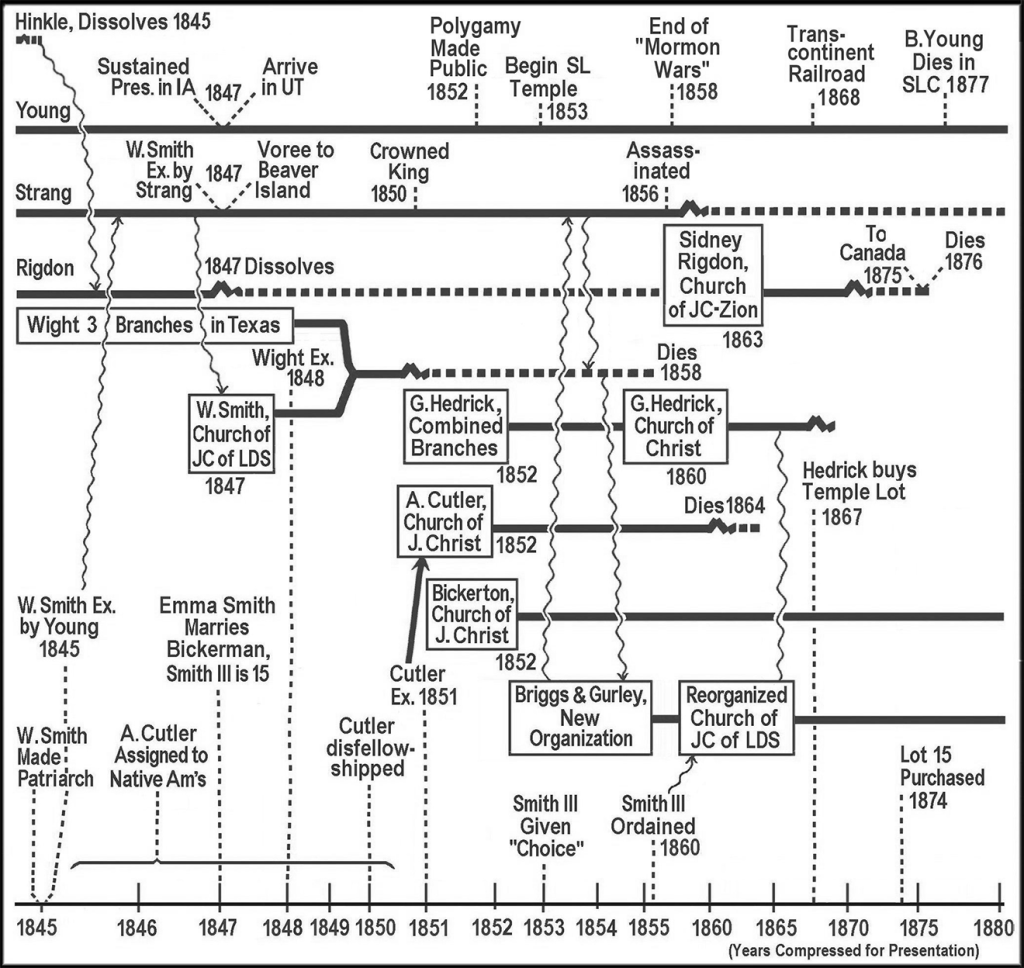

Part One provided information about doctrinal similarities and differences across the various expressions of the Restoration. Part Two now presents a timeline of the various aspirants to the mantle of the Prophet who separated from the original church and attempted to set up their own organizations.

Aspirants prior to the martyrdom

From the earliest years of the Restoration, there were individuals who disagreed with either Joseph Smith or with the particulars of doctrine that he claimed had been revealed to him. As mentioned above, some asserted, even during his lifetime, that Joseph Smith was a “fallen prophet.” The following simple biographical sketches note the four influential individuals who initiated the separations and when their departure occurred. Most of the men who claimed the mantle of Joseph did not consider that they were “separating.” They believed that they were providing reorganization, or redirection, for the original church organization. There was a relatively small number of members who separated during the first fourteen years of the church.

[Page 363]Wycam Clark

Soon after Joseph Smith’s relocation to Kirtland, Ohio, in early 1831, a small group of six individuals, who had been initially intrigued and joined the church, came to disbelieve Joseph as a true prophet. Led by Wycam Clark, who claimed that “he was to be the prophet—that he was the true revelator,” they separated from the original church circa 1831 and called their group the Pure Church of Christ. Apostle George A. Smith of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, speaking at a church conference years later, referred to Clark and his expression as follows: “They had two or three meetings; but the society would never have been known in the world, had not a few of us remembered the circumstance and told of it.” The Wycam-led expression dissolved in the same year as it was established. It is generally regarded as the first separation from the main body of the church. Since the first expression of the Restoration was the original church organized by Joseph Smith, this new group could be considered the second expression.117

Warren Parrish

Baptized in 1833, Warren Parrish was ordained a Seventy in 1835. He was actively involved in the Kirtland Safety Society of which he was the cashier. The Kirtland Safety Society was a financial institution or bank established by church leaders in the fall of 1836 to facilitate the need for cash, which was exchanged for non-liquid assets (primarily land). Heavy demand for the redemption of the notes (the cash value of their issued notes), fueled by the land speculation, led to a suspension of payments within the first month of operation and, coupled with a nationwide banking panic in the spring of 1837, brought about the institution’s closure in November 1837. Parrish was subsequently accused of fraud by many of the note holders within the Kirtland community.118

Beyond the controversial issues of the Safety Society, however, was a broader concern expressed by Parrish and others—they questioned Smith’s leadership and, more specifically, whether he could be a true prophet if he were involved, as he was, in a failed bank [Page 364]that left many of his followers in dire financial circumstances. Led by Parrish, who had emerged as a leading critical voice and an opponent to Smith, dissenters formed their own organization in the summer and fall of 1837, which they called the Church of Christ. This group included John Boynton, Lyman Johnson, and Luke Johnson who had all been members of the original 1835 Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, as well as Martin Harris, one of the Three Witnesses of the Book of Mormon. Both Lyman and Luke Johnson had sent letters to the “Bishop & his council in Kirtland and the Stake of Zion” in May 1837 to “prefer charges against” Joseph Smith.119 Parish and twenty-seven others were excommunicated during the late months of 1837.120 Parrish’s Church of Christ ceased to function circa 1838.

George Hinkle

A colonel in the Missouri state militia, George Hinkle was generally regarded as either “a Benedict Arnold” or the “betrayer of Joseph Smith.” He received these epithets when he convinced Smith to meet with General Samuel D. Lucas at Far West, Missouri, on 31 October 1838 under a “white flag.” Hinkle had convinced Smith to discuss a peaceful solution to the difficulties that had placed the church in an armed adversarial position in northern Missouri in the late summer and fall of 1838. Instead, Smith and others were arrested, put in chains, and transported to Richmond, Missouri. They were tried and imprisoned during the winter of 1838–39 in Liberty Jail, awaiting another trial in Richmond.

George Hinkle quickly left Far West. He was excommunicated in March 1839. Approximately eighteen months after his departure, he organized the Church of Jesus Christ, the Bride the Lamb’s Wife, at Moscow, Iowa, on 24 June 1840. Hinkle, an old friend of Sidney Rigdon, merged his organization with Rigdon’s in the spring of 1845.121 The last meeting of Hinkle’s expression was 16 June 1845.122

[Page 365]William Law

William Law was chosen as Second Counselor in Joseph Smith’s First Presidency at Nauvoo in January 1841. He was excommunicated for apostasy on 18 April 1844. Ten days later, William and his brother Wilson, along with Robert and Charles Foster and Francis and Chauncey Higbee, organized a separation from the Smith-led church, which they titled the True Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. Law continued to work personally for the overthrow of Smith and was a principal participant in publishing the Nauvoo Expositor. As previously noted, the subsequent destruction of the Expositor press on 10 June 1844, following its one and only publication on 7 June, was the primary event that resulted in the assassination of Joseph and Hyrum Smith on 27 June.123

Law’s expression dissolved shortly after its organization. William Law, his brother Wilson, and Robert Foster, together with their families, quickly left Nauvoo on 12 June 1844 aboard the “Steamboat for Burlington, Iowa,” a two-day trip. From Burlington they subsequently moved to Hampton, Illinois.124

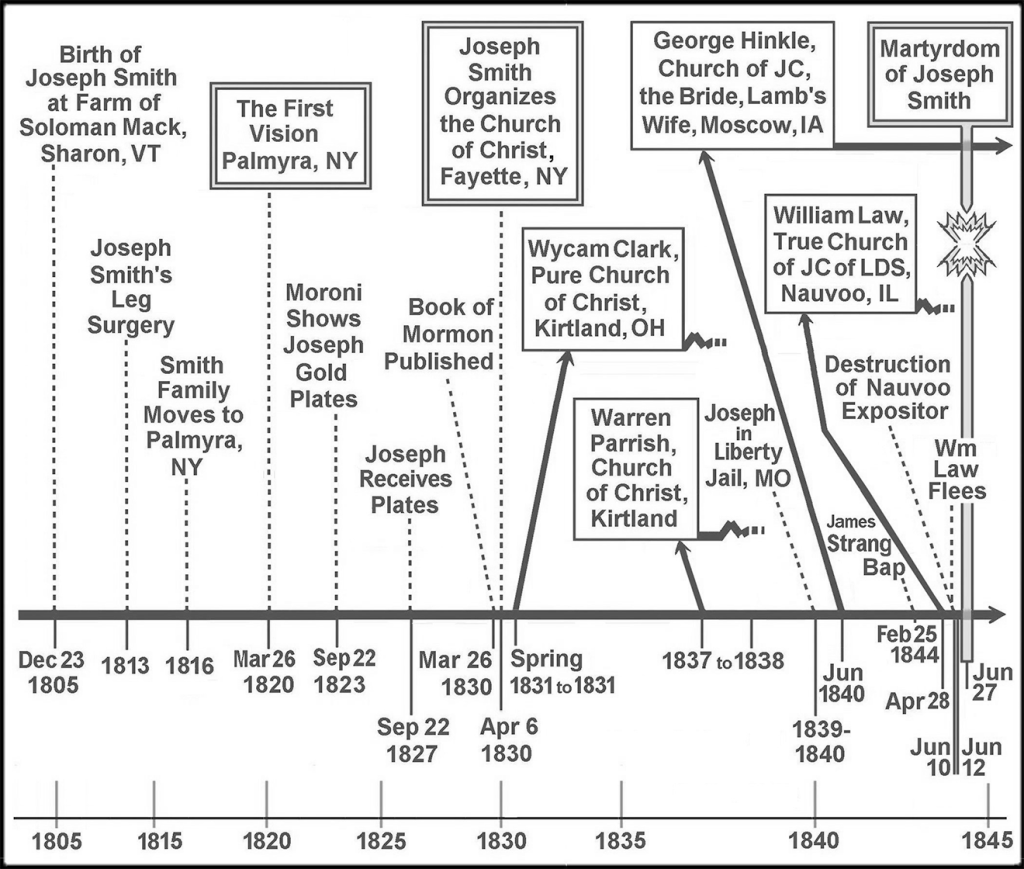

Figure 2 summarizes the significant events of the Restoration prior to the Martyrdom as well as highlighting the four men who separated from the original church to begin their own expressions.

Early 1844 aspirants and major events

In addition to the four men who broke away from the original church prior to the martyrdom of Joseph Smith, several men led separations immediately following the martyrdom. In discussing these post-martyrdom expressions, the following question is often asked: “Why was there so much confusion regarding leadership of the church in the aftermath of the martyrdom?” The answer is simply that Joseph Smith left no unambiguous instruction regarding succession. Some of his actions and pronouncements led to varying interpretations as to his intent. It appears that Smith had previously designated several different individuals as his successor (implied or otherwise).

Figure 2. Timeline for pre-martyrdom aspirants and events up to June 1844.

Both Oliver Cowdery and Hyrum Smith had been specifically designated as “Associate President”125 or “Assistant President,”126 as had John C. Bennett.127 All three individuals had been set apart or ordained to that position. In addition, Joseph had stated that the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles was “equal in authority” to the First Presidency. Finally, he had apparently provided his oldest son with three separate blessings suggesting his succession to his father’s position in the First Presidency. As a consequence, the surviving membership of the [Page 367]church were deeply divided as to the direction regarding the transition of leadership subsequent to his unexpected and early death. Given this confusion and lack of agreement regarding a successor, several men stepped forward to claim the mantle of the deceased prophet. These aspirants played a major role in complicating Brigham Young’s efforts to keep the Nauvoo-based church intact.

Each individual cited in the remainder of this paper was successful in leading adherents away from the Nauvoo-based church. As mentioned in the introduction to Part Two of this essay, other actors will be discussed in brief sketches along with the development of their expressions and the location associated with their movements. I will begin with those whose claims were staked immediately following the martyrdom (see figure 3).

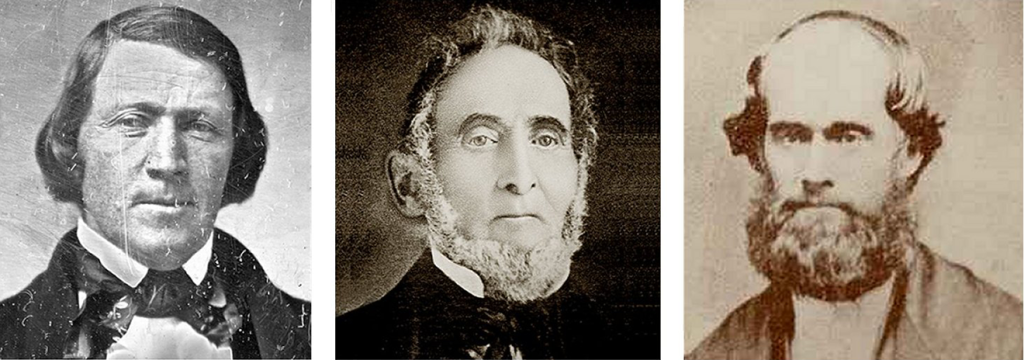

Figure 3. 1844 aspirants to the mantle of the Prophet, Joseph Smith, left to right: Brigham Young, Sidney Rigdon, and James Strang.

In late January 1844, the national election was beginning to become a contentious political focus.128 Fearing to associate with a religious controversy and fearing to lose the Missouri vote, none of the known candidates from either party would take a position favorable to the plight of the saints over the problems they experienced in Missouri. In response, Joseph Smith announced his own candidacy for President of the United States.129 The Nauvoo Neighbor (a church publication), in its issue of 28 February 1844, carried the official announcement of his candidacy in an article titled “For President, Joseph Smith.”130 During the next three months (March to May) members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles left on missions to the various states to proselytize [Page 368]and/or to campaign. Two of their number, however, did not go east, as they had other assignments. John Taylor was the editor of the Times and Seasons and Willard Richards was serving as Joseph Smith’s secretary.

Taylor and Richards would both spend the last days of the prophet’s life with him. Both men were also imprisoned with him and his brother, Hyrum, in Carthage Jail when it was stormed by the mob that killed Joseph and Hyrum. Taylor was severely wounded, having been shot four times. Richards miraculously escaped the barrage of bullets that filled the room that tragic afternoon. He escaped without a scratch, except for a graze on the lower tip of his left ear. At some point after the mob had fled, Richards realized that his life had been spared as a result of a prophecy Joseph had made to him over a year previous. Joseph had told Richards at that time “that the time would come that the balls would fly around him like hail, and he should see his friends fall on the right and on the left, but that there should not be a hole in his garment.”131

During the precarious weeks following the murders at Carthage, John Taylor was bed-ridden and healing from the wounds he had received at Carthage. He made himself available, on a limited scale, for consultation on church matters. Richards did his best to keep the church focused and intact and from members taking any retaliatory measures against known enemies of the church. The 1 July 1844 issue of the Times and Seasons featured an article penned by Richards and Taylor addressed to the branches of the church, “urging the Saints to remain steadfast in the faith and to be peaceable citizens.”132

The majority of the Quorum members in the East received word of the death of Joseph and Hyrum through stories published in newspapers where they were serving. Individually, or in small groups, they returned to Nauvoo as quickly as possible, with the exception of William Smith and John E. Page.

William Smith had received a mission assignment to strengthen branches of the church and was temporarily residing in Philadelphia. On 9 July 1844, while meeting with apostle Heber C. Kimball in Salem, Massachusetts, he was shocked to learn of the death of his brothers in the local newspapers.133 A letter from Willard Richards, William later [Page 369]reported, warned him “not to return to the scene of the recent sad events,” as it might “continue the excitement and endanger not only my own life . . . but perhaps hundreds, even thousands of the saints.”134 Furthermore, his wife, Caroline, was in ill health and unable to travel. They left Philadelphia for Nauvoo some ten months later, in April 1845, arriving in Nauvoo on 4 May 1845.135

John E. Page had been assigned a mission to Pittsburg by Joseph Smith at the April 1843 conference of the church. Subsequent assignments, and a very independent spirit, put him at times in a difficult position with Smith and members of his quorum. For whatever reasons, Page did not return to Nauvoo until early December 1845.136

Parley P. Pratt was the first of the proselyting apostles to return to Nauvoo. He arrived on 10 July and was an immediate help to Willard Richards. Pratt recorded that Richards and he “united in daily councils at Bro. Taylor’s, who was confined by his wounds, and counseled for the good of the church.” Pratt was impressed that Richards and Taylor had men “already renewing their labors on the temple.”137

The next apostle to arrive was George A. Smith. He returned on 27 July and, like Pratt, was an important addition to the leadership needs at this critical time.138 Pratt later stated that they (the four apostles) were “enabled to baffle all the designs of aspiring men . . . and to keep the Church in a measure of union, peace and quiet till the return of President Young and the other members of the quorum.”139

With the arrival of apostles Brigham Young, Heber C, Kimball, Wilford Woodruff, Lyman Wight, and Orson Pratt on the evening of 6 August, nine members (more than a majority) of the Quorum were now present in Nauvoo.140 At this juncture, the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles assumed control of the church with Brigham Young taking charge as its president.141 The arriving five apostles were apprised of the situation regarding Sidney Rigdon and his planned appeal for [Page 370]control of the church, which was to be made to the saints at a conference set for the morning of 8 August.

Sidney Rigdon during 1844

Sidney Rigdon was born on 19 February 1793, in St. Clair Township, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. He was an early convert to Mormonism, joining the infant church on 8 November 1830 at Kirtland, Ohio. At the time of his conversion, he was a Campbellite or Reformed Baptist preacher in Mentor, Ohio, near Cleveland. Rigdon’s influence with his congregation had produced great success for the four missionaries who had traveled to Mentor enroute to western Missouri in the late fall of 1830. Rigdon quickly converted and he soon became an early leader in the growing church. He was chosen to serve as First Counselor in the First Presidency on 8 March 1832, and served in that significant capacity until Smith’s death.

However, by 1842, Smith had begun to have concerns about Rigdon’s loyalty and diminished efforts in his calling and responsibilities.142 Smith’s frustration reached its apex at the October 1843 conference of the church. Speaking to the assembled saints, he formally proposed that Rigdon be dropped from his position of First Counselor. However, Hyrum Smith next spoke in defense of Rigdon. The result was that when a vote was called, Rigdon was retained. To this announced decision, Joseph Smith allegedly said, “I have thrown him off my shoulders, and you have again put him on me. You may carry him, but I will not.” A contemporary and more sympathetic account of this delicate confrontation was printed in the next issue of the Times and Seasons. In the article, Smith “expressed entire willingness to have elder Sidney Rigdon retain his station, provided he would magnify his office . . . but signified his lack of confidence in his integrity and steadfastness, judging from their past intercourse.”143

Rigdon vacated Nauvoo prior to the culminating events that led to the martyrdom and had removed his family to the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, area. His purpose in leaving for Pittsburgh, ostensibly, was his appointed political mission, as he had only recently been chosen as Joseph Smith’s vice-presidential running mate. Upon hearing [Page 371]of Smith’s murder, Rigdon quickly returned to Nauvoo, arriving on Saturday, 3 August 1844.144

As Joseph Smith’s First Counselor for the previous twelve years and his position as his vice-presidential running mate, Rigdon was a formidable claimant to the mantle of Joseph Smith. Upon his arrival, he purposely distanced himself from the apostles who were in town and sought to persuade the saints that he, as Joseph’s “Spokesman for the Church,” should assume the leadership.145 Ignoring a request from Willard Richards, Parley P. Pratt, and George A. Smith to meet at 8:00 am at John Taylor’s home on Sunday, 4 August, Rigdon spoke at worship services being held that morning in Nauvoo. He emphasized his long-time role as Spokesman to the Church, telling those in attendance that it was “the Lord’s wish that ‘there must be a guardian appointed to build up the Church to Joseph.’”146 Prior to the Sunday services, Rigdon had previously asked Nauvoo Stake president William Marks to arrange a special assembly of the saints where he could present his position and receive a sustaining vote or agreement of the Saints to lead the church as Guardian. Marks, who tacitly agreed with Rigdon’s claim, readily accommodated and scheduled the conference for the morning of 8 August 1844, an event that Marks announced at the afternoon session of the Sunday worship services.147

Brigham Young and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles during 1844

As the president of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of the original church at this critical time, Brigham Young was the “key figure” in the immediate leadership crisis aftermath of the martyrdom. Young had joined the early church on 14 April 1832.148 He had been chosen as a member of the original Quorum of the Twelve in 1835149 and had [Page 372]become president of the Quorum after the death of David Patten in October 1838.150

As previously mentioned, at the time of the martyrdom, most of the apostles were in the eastern states on missions. Brigham Young and his four apostle traveling companions arrived in Nauvoo on the evening of Monday, 6 August. They were immediately apprised of the situation concerning Sidney Rigdon and his planned appeal to the saints at the hastily scheduled conference set for 8 August. Sensing the urgency of the situation, Brigham Young called for a special meeting the next day for the Quorum of the Twelve, the Nauvoo High Council, and the High Priest’s quorum, including Sidney Rigdon.

In proposing that the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, of which he was president, should lead the church, Young believed he was acting in accordance with a March 1835 revelation to Joseph Smith, which stated that the Quorum is “equal in authority” to the First Presidency (D&C 107:23–24).151 Where there is no First Presidency—that body dissolved on the death of the president—the presiding church officer was, therefore, the president of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. That office was determined by the seniority of an ordained member of the Quorum. Additionally, on 26 March 1844, Joseph Smith had instructed the Council of Fifty (which included the members of the Quorum of the Twelve) on several significant points of doctrine, including the keys of the Priesthood. After imparting what was on his mind, Smith declared, “I roll the burthen and responsibility of leading this church off from my shoulder on to yours.” This declaration has become known as the “Last Charge.”152

The confrontation on 7 August 1844

At the urgently arranged meeting of 7 August, and upon the invitation of Brigham Young, Sidney Rigdon was invited to explain his position regarding the claim to be Guardian for the church. In response, Rigdon stated that he had been ordained as a spokesman by Joseph [Page 373]Smith and, as such, “the Saints had to acknowledge that all revelations from Joseph Smith would have to come through him.”153

To this assertion, Brigham Young replied, “I do not care who leads the church . . . but one thing I must know, and that is what God says about it.” Brigham continued, “I have the keys [as president of the Quorum of the Twelve] and the means of obtaining the mind of God on the subject. . . . Joseph conferred upon our heads all of the keys and powers belonging to the Apostleship.” With this pointed exchange between Rigdon and Young, the stage was set for the following day.

The conference on 8 August 1844

On the morning of 8 August, the hastily convened conference was held, attended by upwards of 5,000 people.154 In the morning session, Rigdon made his formal claim as Guardian for the church. Rigdon’s lengthy ninety-minute oration apparently did not motivate the assembly as he had anticipated.

In the afternoon session, Brigham Young took the podium. He advised the saints of the role and responsibility of the Twelve Apostles.155 In a two-hour long exhortation, he then laid out the particulars and reasons why the Lord expected the Quorum of the Twelve to lead the church. Among the highlights of his discourse was this provocative question: “Here is Brigham, have his knees ever faltered?” According to his great-grandson, S. Dilworth Young, Brigham’s answer to his [Page 374]rhetorical question “carried the day.”156 Many of those who attended later testified that they “saw the Prophet Joseph speaking” to them instead of Brigham. Others claimed they “heard the voice of Joseph.” And still others stated that they “felt” the mantle of the deceased prophet rest upon Brigham Young.157

Of course, there are those like Richard S. Van Wagoner who claim that these recitals, provided years later and with no known contemporary account available, simply reject these later retellings of the event as a “myth.”158 Daniel C. Peterson, in a recent article titled “The Heavenly Sign: Brigham’s Transfiguration at Nauvoo,”159 concurs with Lynne Watkins Jorgensen that the preponderance of the accounts of this significant event, either orally or in writing, by at least 129 documented individual testimonies, provides validity for this remarkable manifestation.160 Historian Ronald K. Esplin stated, “Though there is no contemporary diary account, the number of later retellings, many in remarkable detail, argues for the reality of some such experience.”161

Following Young’s remarks, a vote was taken. The saints were given two options: “Do you want Brother Rigdon to stand forward, your guide, your spokesman?” Or “does the church want, and is it their only desire to sustain the Twelve as the First Presidency of this people?”162 There was an almost universal affirmative vote in favor of the Twelve.

James Strang during 1844

No sooner was the 8 August 1844 conference concluded than another formidable aspirant made his own position known. Through an emissary, the members of the Nauvoo-based church were unexpectedly informed that the leadership of the church should be entrusted to [Page 375]James J. Strang, a new member of the church who was living in a branch in Wisconsin.

Strang was born on 21 March 1813 at Scipio, New York. He was thirty-one years old when he was introduced to the teachings of the church. Intrigued by the doctrine he heard from missionaries, he traveled to Nauvoo from his home in Spring Prairie, Wisconsin, to get a first-hand look at the church and to meet the Prophet of whom he had heard so much. At Nauvoo, he met Joseph, was convinced, and converted. He was baptized on 25 February 1844 by Joseph Smith and ordained an elder on 3 March 1844 by Hyrum Smith. Soon thereafter, he returned home to Spring Prairie, Wisconsin.

On 9 July 1844, Strang first received the news of the murder of Joseph Smith. He also stated that on that same day he received a letter written to him by Smith. It was dated 18 June 1844, only ten days before the martyrdom.163 Although he had been a member of the church for less than four months, this letter indicated that he was to be the successor to Smith and receive the mantle of the Prophet. The contents of the letter also included a revelation specifically stating that the future gathering place of the saints was to be in the area of Strang’s current residence in Spring Prairie, which was to be renamed. The revelation stated, “The name of the city shall be called Voree, which is interpreted, garden of peace, for there shall my people have peace and rest.”164 Strang also told of a personal angelic confirmation to lead the church. He later stated that at 5:30 on the afternoon of 27 June 1844, within minutes of the assassination of Joseph and Hyrum:

[T]he Angel of God came unto him and saluted him, saying: “Fear God and be strengthened and obey him, for great is [Page 376]the work which he hath required at thy hand.” . . . The Angel of the Lord then stretched forth his hand unto him and touched his head, and put oil upon him and said, “Grace is poured upon thy lips, and God blessed thee with the greatness of the Everlasting Priesthood.”165

Imbued by this personal visitation and the letter from Joseph Smith, Strang set out for a conference of local church leaders being held in Florence, Michigan, on 27 July 1844. On 5 August 1844, he presented his letter to the presiding elder of the branch, Crandall Dunn. Dunn and others denounced his claim, and Strang was excommunicated that same day.166 Strang became ill following the conference and returned to his home in Spring Prairie, Wisconsin. Unable to travel to Nauvoo and present his claim, he sent Moses Smith, an uncle by marriage, to present his letter and his angelic confirmation to the leadership.167 In Nauvoo, Moses Smith presented Strang’s letter and claim to all those who would listen. Brigham Young, not surprisingly, disputed Strang’s leadership claims. Strang was excommunicated a second time on 26 August 1844.168

Notwithstanding his excommunication, Strang’s claim resonated with some members who were dissatisfied with their options of Brigham Young or Sidney Rigdon—especially with the doctrine of plural marriage. The result of Strang’s missionary work, which was carried out by himself and others, was his leading 500 to 1,000 followers169 from Nauvoo and the scattered branches—primarily in northern Illinois, Wisconsin, and Michigan—to Spring Prairie, Wisconsin, which he had renamed Voree as instructed in Smith’s letter of appointment. Part of his success was likely due to a rejection of the doctrine of plural marriage introduced by Joseph Smith and supported by Brigham Young—this despite the fact that several years later, Strang adopted the principle of polygamy. In any case, his followers at the time included such notables as the Nauvoo Stake president, William Marks; Joseph Smith’s brother, William Smith; his mother, Lucy Mack [Page 377]Smith; and apostle John E. Page. Strang retained the same 1844 name for his church organization, i.e., the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, since he claimed he was simply “assuming” the leadership of the existing church. Over the next few months, Strang urged his adherents and recent converts to relocate to Voree.170

Sidney Rigdon, remainder of 1844

Despite the vote taken at the conclusion of the 8 August 1844 conference, the articulate and highly influential Sidney Rigdon did not curtail his proselyting efforts in and around Nauvoo. Throughout the summer of 1844, he continued to advocate the same positions he had championed prior to and at the conference, namely that he had been, or was, the first counselor in the First Presidency, Joseph Smith’s vice-presidential running mate, and the Guardian for the church. The result was that he was successful in gathering many undecided individuals to his stated position. Brigham Young, after being informed of Rigdon’s ongoing proselytizing efforts, coupled with his defaming members of the Quorum—especially Brigham—called for a church court. On 8 September 1844, Rigdon was tried for his church membership. Rigdon chose not to attend this meeting at which he was excommunicated.

Two days later, Rigdon departed Nauvoo for Pittsburgh.171 Upon his arrival in mid-September 1844, Rigdon’s supporters and sympathizers rallied around him and, within a month, he had organized a church with himself as First President. Rigdon wasted little time in launching a newspaper with a familiar name to his followers: Latter Day Saints’ Messenger and Advocate.172 The first publication appeared on 15 October 1844 and it, like many of the early issues, carried letters that supported Rigdon and, at the same time, denounced the claims of the Twelve Apostles in Nauvoo.173

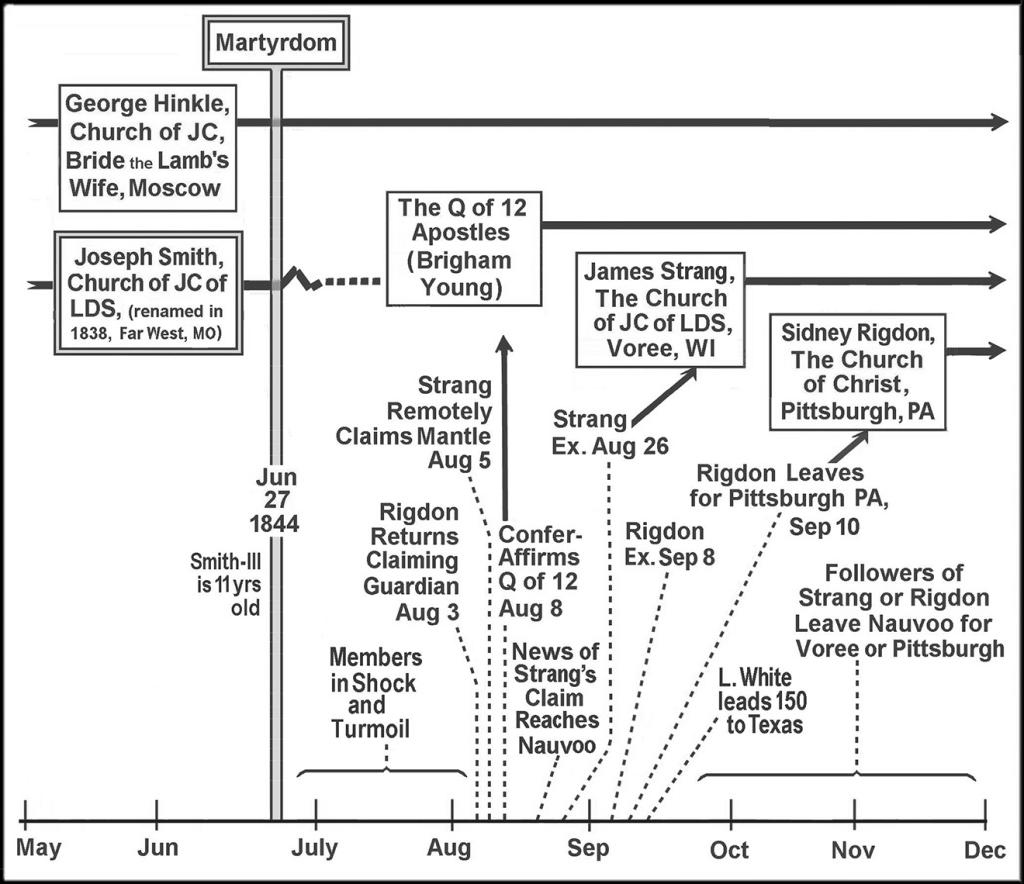

Figure 4 summarizes the main events in the tumultuous year of 1844.

Figure 4. Timeline for post-martyrdom aspirants and events, June to December 1844.

Post-martyrdom aspirants and developments after 1844

In the years after 1844, both Rigdon and Strang moved forward with their own expressions in Pennsylvania and Wisconsin/Michigan, respectively. During the ensuing twenty-plus years, new challenges would arise. Church members in a growing array of expressions would be challenged by advocated doctrines and new aspirants to the mantle of the Prophet Joseph Smith. Lineal rights would become a major factor, as would the doctrines that Joseph refined and emphasized and that Brigham Young promoted, such as baptism for the dead and plural marriage.

Figure 5 shows the eight additional aspirants not previously pictured in figure 3.

[Page 379]

Figure 5. Later aspirants to the mantle of the Prophet Joseph Smith, left to right (top row): Lyman Wight, William Smith, Granville Hedrick, and Jason Briggs; (bottom row): Zenos Gurley, Alpheus Cutler, Joseph Smith III, and William Bickerton.

Sidney Rigdon after 1844

On 6 April 1845, Rigdon and his adherents convened in Pittsburgh for the annual conference of their newly organized expression of the Restoration. Rigdon’s adherents decided to rename their church. They chose to return to the original name of the 1830 church, i.e., the Church of Christ.174

During late 1844 and throughout 1845, Rigdon’s church continued to grow as several hundred members gathered to Pittsburgh and vicinity.175 At the April 1846 conference, Rigdon announced a revelation regarding the location of the New Jerusalem. It was to be in the Cumberland Valley, about 300 miles to the east, to which the majority of his church adherents relocated. For a variety of reasons, his organization disintegrated just a year later, in April 1847.176 Rigdon was forced to move to Cuba, New York, where he was given a place to live by his son-in-law, George W. Robinson. Two years later, the Robinsons and Rigdons moved to nearby Friendship, New York.177

Several years later, encouraged by supporters who again sought out Rigdon, a second attempt to formalize a church began in the late [Page 380]1850s. With his persuasive preaching, the Church of Jesus Christ of the Children of Zion was officially established in Philadelphia in July 1863. A standard topic taught by Rigdon was the concept of Zion, which resulted in a “new Zion” located in the middle of Iowa. Rigdon, however, did not move from his home in Friendship, New York. Rigdon’s new expression began to dissolve in 1871. Those who remained committed subsequently moved to southern Manitoba, Canada, in 1875.178 Health issues caused Rigdon to stay homebound in the 1870s. In 1872, he suffered a stroke. He died on 14 July 1876 at Friendship, New York.179

Brigham Young after 1844

The historical record is clear that most church members chose to follow the leadership of Brigham Young and the Quorum of the Twelve. Providing the needed leadership to these members in Nauvoo, the rest of the country, and abroad was an ongoing challenge for Young and the Twelve. In April 1845, a lengthy letter of appeal and hoped for direction was addressed to U.S. President James K. Polk. There was no corresponding offer of relief.180 As a result, and with persecution starting to resurge, staying in Illinois became impractical.

Plans were made to immigrate as a body to the Great Basin of the American West with a beginning departure date of April 1845. Nauvoo became a frenzy of activity as wagons were made and outfitted for the exodus planned for 1846. The completion of the Nauvoo Temple was also a high priority. When the first floor was ready for use, the full ordinance of the endowment was administered to the saints beginning 10 December 1845 and continuing until 7 February 1846. During that brief period of approximately sixty days, a total of 5,615 church members were endowed.181

During this time, there was increased persecution and indictments that charged Young and the apostles with various crimes. There were also rumors of a military intervention to keep Young’s planned western movement from establishing an independent commonwealth in Mexican Territory. Given this emerging crisis, Brigham Young and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles decided it was time to begin the [Page 381]westward trek earlier than had been anticipated. Despite the bitterly cold weather, the exodus began on 2 February 1846. By 15 February, Young himself joined the growing camp across the Mississippi River in Lee County, Iowa. Throughout 1846 and thereafter, thousands of saints traveled across Iowa to the vicinity of Council Bluffs. There, Brigham Young created a temporary terminus. In the fall and early winter of 1846, some of the refugees, including Young, traveled over the Missouri River and established what became known as Winter Quarters, in eastern Nebraska (near what is now Omaha).182

In April 1847, Young led the first caravan of Latter-day Saints west from Winter Quarters. The first pioneer party of 148 individuals entered the Valley of the Great Salt Lake beginning 21 July 1847, with Young arriving on 24 July 1847. Young and others left the newly established settlement on 26 August 1847 to return to Winter Quarters and arrived there on 2 October.183

On 5 December 1847, a quorum meeting was held at the home of Orson Hyde, where a reestablishment of the First Presidency was agreed to with Brigham Young as president. Heber C. Kimball was called as First Counselor and Willard Richards as Second Counselor. Following this action, plans were immediately initiated to erect a log structure in Kanesville (Council Bluffs) where a conference of the church could be held to transact business, including the sustaining of the action taken by the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles regarding the First Presidency. The structure was completed in just three weeks. On the morning of Monday, 27 December 1847, over 1,000 men and women crowded into the log tabernacle. The vote was unanimous in the affirmative. Brigham Young left again for the Valley of the Great Salt Lake in the spring of 1848.184 He died in Salt Lake City on 29 August 1877.185

James Strang after 1844

In 1846, a new plan for “the gathering” began to develop for James Strang and his followers in Wisconsin. That summer, Strang claimed [Page 382]a vision that pointed him to a land surrounded by water. On returning home from missionary efforts in the eastern states, the boat on which he was traveling had to take refuge from a severe storm at Beaver Island located in northwest Lake Michigan. Strang was convinced that this was the land he had previously envisioned. In 1847, a few families of converts began moving to this newly designated location. By August 1849, Strang and his family also departed Voree for Beaver Island. Within months, the church headquarters was established on the island. Strang was crowned as “King” by his constituents in an elaborate ceremony on 8 July 1850.186