[Page 41]Abstract: This article explores the biblical pattern that relates the temple-related symbols of the cube, the gate, and measuring tools. The tools of architecture and measurement were associated with the kingship motifs of creation and conquering chaos, and on the day when a person was initiated as a king in ancient Israel, all of these concepts were applied to him.

[Editor’s Note: Part of our book chapter reprint series, this article is reprinted here as a service to the LDS community. Original pagination and page numbers have necessarily changed, otherwise the reprint has the same content as the original.

See Matthew B. Brown, “Cube, Gate, and Measuring Tools: A Biblical Pattern,” in Ancient Temple Worship: Proceedings of The Expound Symposium 14 May 2011, ed. Matthew B. Brown, Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, Stephen D. Ricks, and John S. Thompson (Orem, UT: The Interpreter Foundation; Salt Lake City: Eborn Books, 2014), 1–26. Further information at https://interpreterfoundation.org/books/ancient-temple-worship/.]

The purpose of this paper1 is to draw attention to several sets of matching themes which are found in descriptions of the ancient Israelite temple and portions of the apocalypse written by the apostle John. The information associated with these sets can be applied to the task of interpreting the respective texts where they are found and they can also be used to demonstrate a surprising way whereby the covenant people of the Old and New Testaments were interconnected.

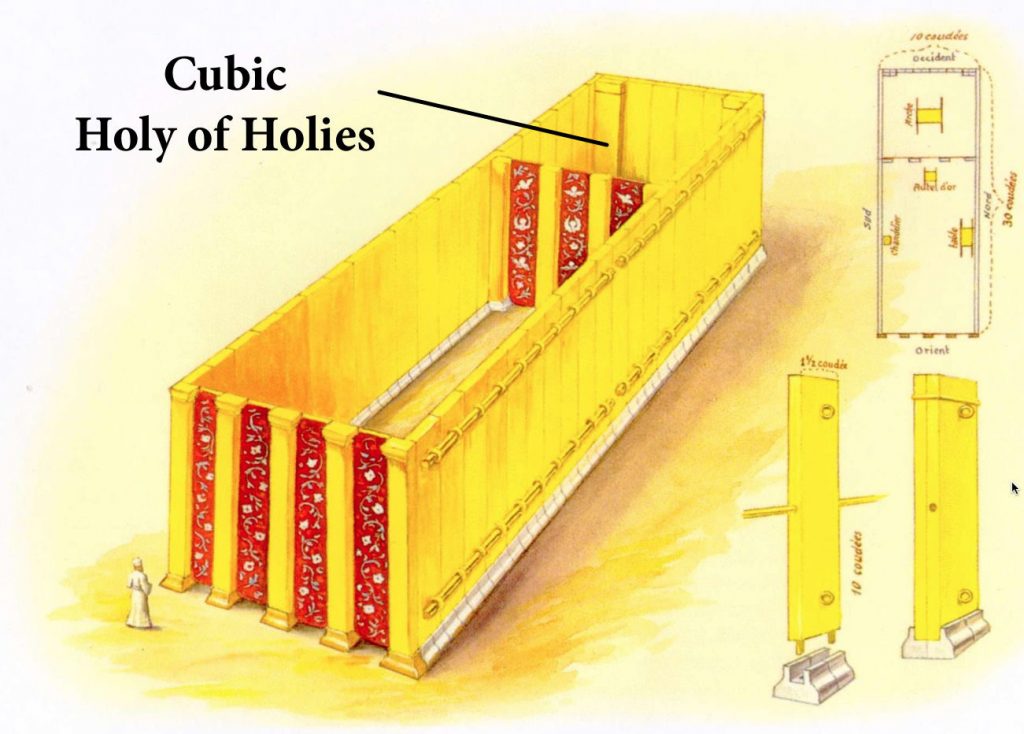

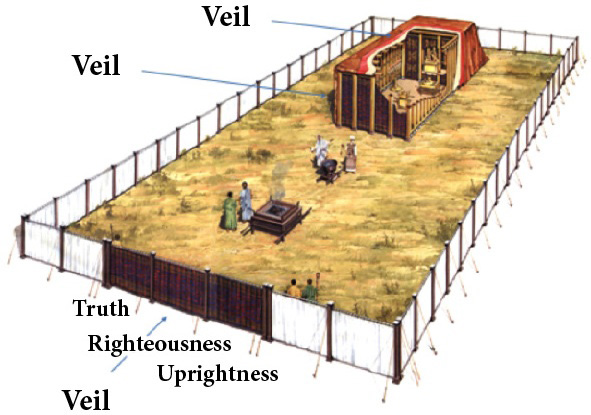

The first point of comparison in the aforementioned matching sets has to do with the most sacred area in the Israelite temple known as the Holy of [Page 42]Holies. The perfectly cubical shape of this room was revealed in a vision to the prophet Moses while he met with the Lord on Mount Sinai (Exodus 25:8–9). Long after Moses incorporated this room into the Tabernacle it was replicated on a larger scale inside of Solomon’s Temple (1 Kings 6:20). Four pillars were placed on the east side of the Holy of Holies of the Tabernacle (Exodus 26:32–33), which logically would have created three narrow gateways that provided access to the room (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Holy Place and the Holy of Holies of the Tabernacle

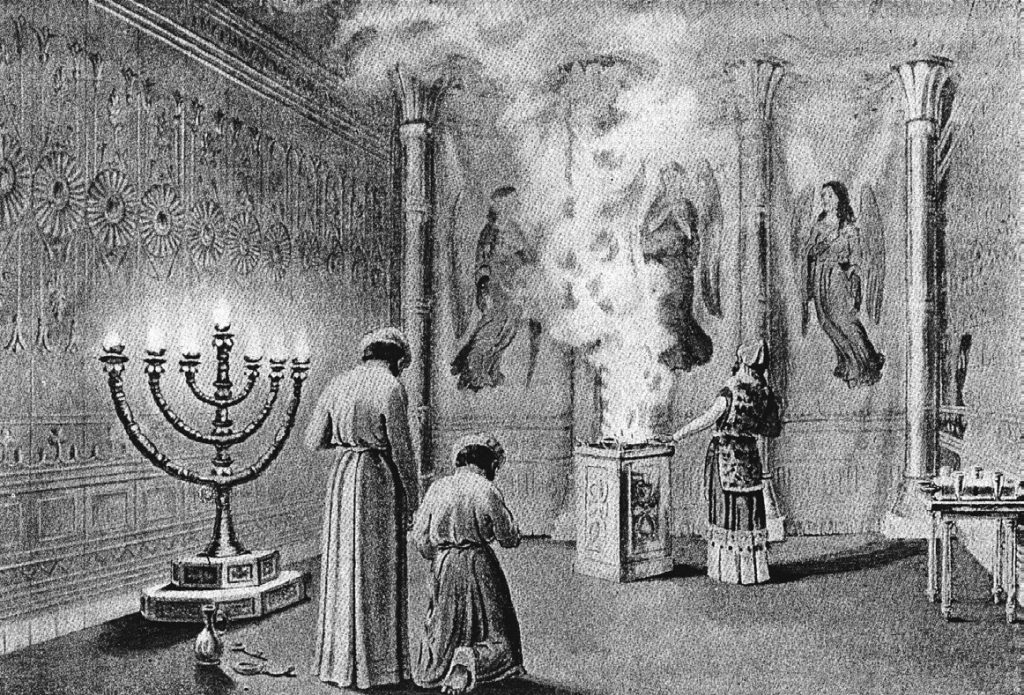

A veil was stretched across these pillars and cherubim, or angelic guards, were embroidered on the veil (Exodus 26:31–32; cf. Genesis 3:24). The exact number of cherubim embroidered on the veil is not stated in any Old Testament text, but, as seen in Figure 2, there may have been been only three: one per gateway. The main reason this idea should be taken into serious consideration is the fact that once it is accepted, a matching pattern then emerges in the last volume of the New Testament.

Figure 2: Interior of the Holy Place.

In chapter 21 of the book of Revelation, the apostle John is shown the heavenly city of New Jerusalem, and he sees that it is shaped like a perfect cube. He also sees that it has three gates on each of its four sides, and one angel is standing guard at each of the gates (vv. 12, 16).

It can be determined with a degree of certainty that the heavenly New Jerusalem and the earthly Holy of Holies were parallel objects because of an important object that each of them contained. The Ark of the Covenant sat in the Holy of Holies of the earthly temple. There are a number of Bible scholars who believe that the Ark of the Covenant was a representation of God’s throne2 — which means that the Holy of Holies would have symbolically represented the throne room of the Heavenly King. When John the Revelator entered into the heavenly New [Page 43]Jerusalem, he saw that the throne of God was there (Revelation 22:3). This explains why John said that he saw no temple inside of the heavenly New Jerusalem (Revelation 21:22). He was standing inside the Holy of Holies of the heavenly temple.

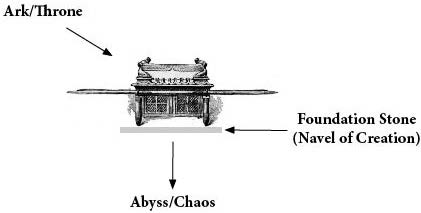

Figure 3 contains notations which are relevant to the discussion at hand. Psalm 29:10 in the King James Bible reads this way: “The Lord sitteth upon the flood; yea, the Lord sitteth King for ever.” This is another way of saying that the throne of God was considered to be stationed over a body of water. In the mythology of ancient Israel (and several other regions of the ancient Near East), it was taught that at the time of creation [Page 44]God conquered chaos — or the chaos monster — which was signified by the boisterous waves of the sea. At one point in time, there was a symbolic rock placed directly in front of the Ark of the Covenant in the Holy of Holies called the “Foundation Stone.” This rock represented the first portion of earth which arose from the sea at the time of creation. It was, therefore, considered to be the center, or navel, of creation, and the Israelites believed that it served as a sort of capstone over the chaotic sea.3 These ideas will play a role in the discussion which follows.

Figure 3: “The Lord sitteth upon the flood;

yea, the Lord sitteth King for ever” (Psalm 29:10)

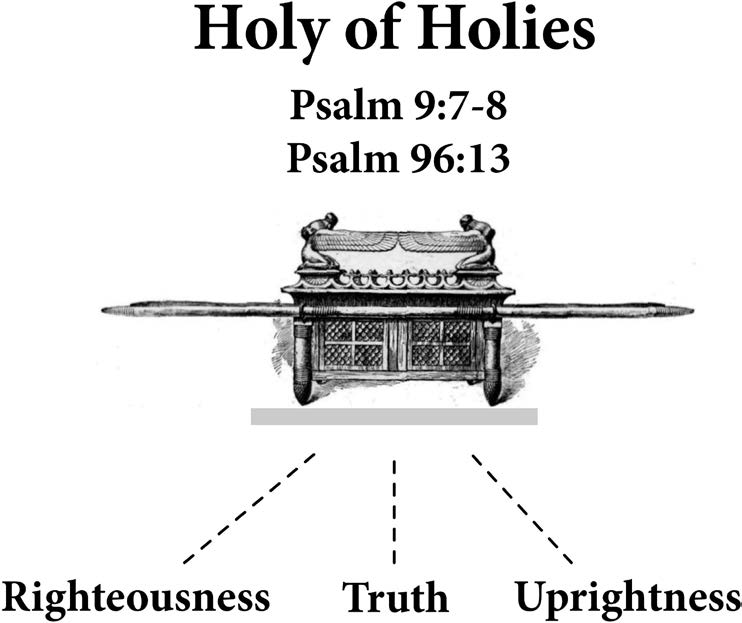

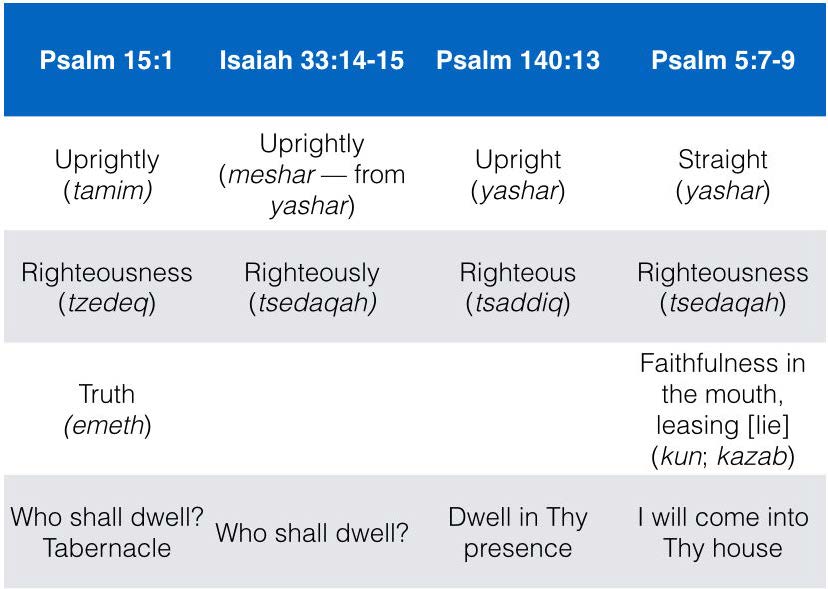

In Figure 4 there are two more references to the book of Psalms. If it is accepted that the Ark of the Covenant represented God’s throne, then these verses from Psalm 9 and Psalm 96 take on added meaning. They say, essentially, that there are specific attributes associated with God’s throne or His kingship. These attributes are listed in the King James Version of the Bible as righteousness, truth, and uprightness. By extension, these throne attributes are connected with the Holy of Holies or throne room.

Figure 4: Three specific attributes associated with

God’s throne or his kingship

This is very significant since there are several Psalms which have been identified as temple entrance liturgies, and one of them (Psalm 15) names the very same throne attributes as requirements for entering through the temple’s veiled gateway.4 What is even more interesting, however, is that if the content of Revelation chapter 21 is considered in this light, it can been seen that the same temple entrance requirements are listed for the heavenly New Jerusalem — they are just named in a slightly different way than in Psalm 15:

Psalm 15:1-2: Lord, who shall abide in thy tabernacle? .… He that walketh uprightly, and worketh righteousness, and speaketh the truth in his heart.

[Page 45]Revelation 21:27: And there shall in no wise enter into [New Jerusalem] anything that defileth, neither whatsoever worketh abomination, or maketh a lie.

Since there were three different veiled gateways in the Tabernacle built by Moses, the question naturally arises as to which gate the temple entrance liturgies applied to. Some early Jewish rabbis taught that the Psalm 24 entrance liturgy was used by the Israelite king in order to gain access to the Holy of Holies,5 while there are some modern scholars who believe that the entrance liturgies were employed by regular members of Israelite society in order to get through the first gate which led into the temple courtyard.6

Figure 5: Veiled gateways of the Tabernacle

Here is a brief description of what happened — according to some commentators — when the Psalm 15 entrance text was being put to use:

- the location was a temple gate.

- the worshipers inquire[d] of the priest as to the qualifications for admission”; this was a question pertaining to “the nature and character of the person who desire[d] to enter God’s presence.”

- “the priest respond[ed] by specifying the requirements.”

- the exchange “conclude[d] with a blessing.”7

One scholar notes that the Psalm 15 question regarding entry requirements is addressed to the Lord because He alone “decides who [Page 46]may appear before Him.” Yet, it is “a priestly speaker” or proxy who answers on the Lord’s behalf from inside of the temple entryway.8

By way of a brief historical digression, it is important to mention two things here. First, if a comparison is made between the book of Revelation Holy of Holies material and some of the teachings of Jesus Christ recorded in Luke chapter 13, an interesting pattern emerges. During a discussion about personal salvation in Luke 13, the Savior states that people will come from the four cardinal directions in order to enter into the kingdom of God (this may be a two-dimensional reference to the cube; reference to the kingdom suggests a throne). Furthermore, Jesus Christ indicates that there will be a gateway for entry into the kingdom, and people will engage in a conversation with a gatekeeper and be told of entry requirements (this, again, suggests the Holy of Holies of the temple). Passage through the gate is not to be automatic or easy, however, as evidenced by Luke 13:24, where the Lord states that the gate is narrow (stenēs),9 and not everyone is granted access. In addition, the Savior alludes to the fact that those who do enter through the gate will have to “strive” to do so. The Greek word that underlies the translation “strive” (agōnizesthe) means to struggle or contend, as in a physical contest.10 The second thing to mention is the act of knocking, which is referred to in Luke 13:25. In Figure 6 a Catholic officiator with a small mallet can be seen engaged in an entrance liturgy. He knocks three times and recites part of Psalm 24 — which is an ancient Israelite temple entrance text. This triple knocking and Psalm citation ceremony can be traced back among normative Christians to a very early period. For example, if Luke 13:22-30 is compared with the chapters 21 and 22 of the book of Revelation a clear set of parallels materializes (see Appendix).

Figure 6: A Catholic officiator with a small mallet as part of an entrance liturgy

Returning now to the temple entrance requirements of Psalm 15; righteousness, truth, and uprightness are the royal attributes of morality which are named as necessary to pass by the Lord’s proxy at the temple gate. It is interesting to note that each of these attributes can be tied to specific architectural tools (next sections of this chapter), which, in turn, can be connected to the entrance liturgies in a secondary way (last sections of this chapter).

[Page 47]Righteousness

Figure 7: An Egyptian merkhet (plumb line), used to measure time

In the Psalm 118 entrance liturgy, the gate of the temple is specifically called “the gate of righteousness,” and in Isaiah 28:17 the Lord states, through one of His temple priests, that He judges “righteousness” by symbolically taking a measurement with a cord or a string. There is some disagreement among scholars over the exact identity of the instrument used by the Lord in His act of judgment, but whether it is a plumb line (the Egyptian instrument in Figure 7 was used to measure time) or a leveling line, it is still the same basic thing — a piece of cord or a string. Hence the temple gate, the moral attribute of righteousness, and the cord or string can be linked to each other.

Figure 8: An Egyptian leveling line

There are a number of places in the Old Testament where God is depicted as utilizing a cord or string in order to measure His covenant people (see 1 Kings 21:13; Isaiah 28:17; 34:11; Lamentations 2:8; Amos 7:7–8). This imagery, says one commentator, is “a metaphor for divine judgment” and “it may be that the idea [being put forward by this act is] a strict, predetermined measure from which God will not deviate.”11

Truth

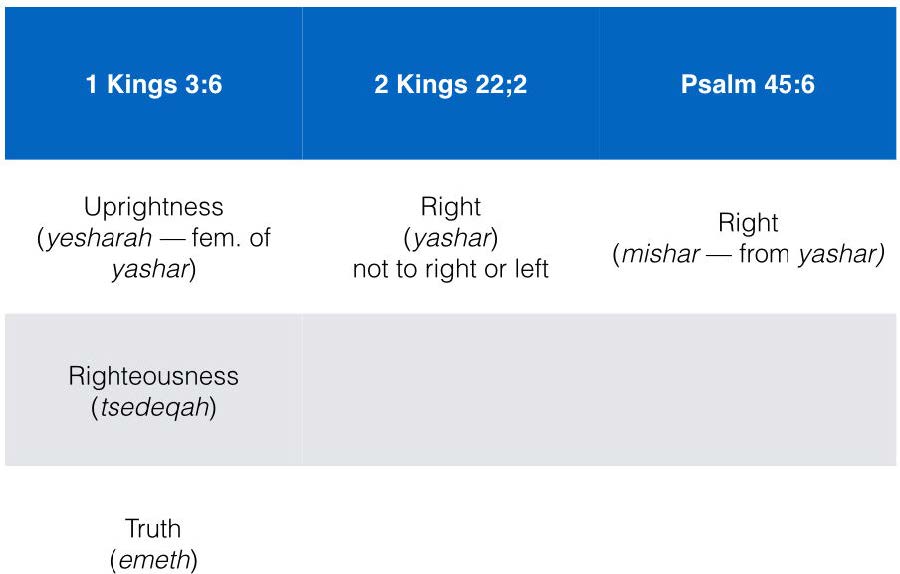

Figure 9: Christ with a compass

The Psalm 15 temple entrance text combines the concept of “truth” with a person’s “heart” (v. 2), while in the book of First Kings, walking in the “truth” with all of one’s “heart” is a divinely mandated prerequisite for occupying the kingly throne in ancient Israel (1 Kings 2:4; cf. Isaiah 16:5).12 Indeed, in Psalm 86:11 the Israelite king proclaims the he will indeed walk in God’s “truth” (cf. Isaiah 38:3; 1 Kings 3:6).13

Psalm 89:8 mentions faithfulness as being “round about” God while a Jewish Targum of the same verse clarifies that it is “truth” which surrounds Him.14 Since the [Page 48]Hebrew word which underlies the King James phrase “round about” (sabib) can be rendered as “circumference” or “circuit,” the general imagery invoked is that of a circle. God being encircled by truth hints at a specific architectural tool employed in constructing a round shape: a builder’s compass.

Uprightness

In Psalm 15:2 the gate entry requirement of acting “uprightly” is a bit problematic since the Hebrew word being translated there does not match a clear pattern of words found throughout the Bible. The Hebrew word tamim underlies verse 2, but the parallel text of Isaiah 33:15 uses a different word for “uprightly” — meshar (see Figure 10). One of the meanings of meshar is “straightness” or “rectitude” in the figurative sense, and it comes from the Hebrew word yashar, which can also be translated as “straight.” This is significant since Psalm 140:13 (which likewise parallels Psalm 15:1–2) says that the “upright” will dwell in God’s presence, but it is translating the Hebrew word yashar, which can be rendered as “straight.”

Figure 10: Comparison of references in the Psalms and Isaiah

Here are some other points to consider (see Figure 11). In 1 Kings 3:6, it is said that the king of Israel walks in “uprightness,” but the word being translated is yesharah, the feminine form of yashar, which can mean “straight.” Evidence that this is an acceptable way to understand the meaning of the Hebrew word can be found in 2 Kings chapter 22, [Page 49]verse 2, where it is made known that the Israelite king did that which was yashar in the sight of the Lord, turning neither to the right nor to the left. This seems to be a clear reference to an undeviating or “straight” line. A reference to God’s throne in Psalm 45:6 is relevant here. It says, “Thy throne, O God, is forever and ever: the scepter of thy kingdom is a right scepter.” The Hebrew word translated here as “scepter” (shebet) can also be rendered as “rod,” and the word that describes it in the King James Bible (i.e., “right”) is a rendition of the Hebrew word mishor which is derived from yashar which can mean “straight.”

Figure 11: Comparison of references in 1 and 2 Kings and Psalm 45:6

Psalm 5 — which has itself been “associated with the “entrance liturgies”15 and is rehearsed by the Israelite king — happens to list some of the Psalm 15 temple entrance requirements within it, but verse 8 of the King James Version actually renders yashar as “straight.” The reason all of this is relevant is that in both ancient Asia and ancient Mesopotamia, a good king was said to wield a “straight scepter.”16

There is an intriguing section of the Old Testament where the rod image is tied together with the cord image, and both are mentioned along with an Israelite temple gate. When the prophet Ezekiel (who was a temple priest) was shown a visionary model of the Lord’s sanctuary, he met an angel in the east entrance of that temple complex. This gateway seems to have served as a station for guards,17 and so it was roughly equivalent to the veiled tabernacle gate with cherubim embroidered upon it. The angel who met with Ezekiel was holding two objects: a linen rope or cord and a measuring reed or rod (see Ezekiel 40:3 and Figure 12). The rod (qaneh) [Page 50]was used for measuring short distances, while the cord measured longer ones.18 It should be noted that in ancient Mesopotamia, the “rod and ring” motif (which has been identified in some instances as a “rod and rope”) is interpreted by several scholars as “surveying tools used for laying straight lines,” “tools for laying out straight foundations.” Ideologically, it is said that a deity would interact with the earthly Mesopotamian king so that he would be able to “guide the land straight.” A deity is sometimes depicted on Mesopotamian monuments actually handing the aforementioned objects to the earthly king. It is believed by some writers that these two items signified “righteous kingship sanctified by the gods.”19

It seems pertinent that the rod and cord motifs can be detected both directly and indirectly in association with the Holy of Holies cube described in the book of Revelation. Just like in the book of Ezekiel, the angel of Revelation uses a rod to measure the temple (Revelation 21:15-17). The text does not say that the Revelation angel carried a measuring cord like his counterpart in Ezekiel’s book, but the cord is implied by the fact that Ezekiel’s angel used his cord to measure the life-giving river of water coming out of the temple, while the book of Revelation actually describes the life-giving river of water issuing forth from God’s throne inside the Holy of Holies cube.

There is one additional point to make with regard to Figure 12. The apostle John states in Revelation 11:1 that he was handed a “reed like unto a rod” by an angel and instructed to use it to measure people who [Page 51]were in the temple. The word translated there as “rod” is rhabados and can be rendered as “scepter,” which is appropriate because John indicates that at some point in time he himself had achieved the status of kingship (see Revelation 1:5–6) and, like it has previously been stated in this paper, kings measure people as an act of judgment.

Figure 12: Ezekiel with an angel holding a linen rope or cord

and a measuring reed or rod

Figure 13 displays a model of the visionary temple shown to the prophet Ezekiel and at the bottom can be seen an arrow pointing to the location of the gate where the angel stood with the cord and the rod. Off to the left is another arrow pointing to an inner gateway, and the explanation I will now give will provide the bridge to the concepts presented in the remainder of this chapter. It was at this temple gate that the king of Israel was to kneel and worship the Heavenly King at the gate of the inner court. Ezekiel 46:1–2 mentions that one of the times when the earthly king was required to do this was on the Sabbath — after “six working days” — which is a clear reference to the creation theme. Psalm 5, which has been “associated with the “entrance liturgies,” depicts the Israelite king entering the temple complex and bowing down (shachah) or kneeling toward the temple proper, where the throne of God was located20 (cf. Psalm 95:3, 5-6).

Figure 13: Exterior of the Temple of Solomon showing the location of the two gates mentioned

This all leads to a rather peculiar aspect of the temple entrance liturgy texts:

[Page 52]Psalm 24:1-2: The earth is the Lord’s, and the fulness thereof; the world, and they that dwell therein. For he hath founded it upon the seas, and established it upon the floods.

Revelation 21:1, 5: And I saw a new heaven and a new earth: for the first heaven and the first earth were passed away; and there was no more sea .… And he that sat upon the throne said, Behold, I make all things new.

At the very beginning of Psalm 24, there is a distinct reference to the creation of the earth which evokes the “center” or “navel” imagery mentioned earlier — i.e., the earth is founded on the sea. Some scholars find in this passage a reference to the “conquering chaos” theme and God’s dominion or kingship.21 The argument for a “conquering chaos” theme is strengthened by the fact that Revelation 21, verses 1 and 5, repeat the earth and sea motifs, and their context has been identified as that of creation and conquering chaos.22

The question to ask, then, is this: “Why are creation and conquering chaos themes placed in association with a temple gateway entrance liturgy?”

The answer may lie in a theme which has been discussed throughout this paper — measuring tools. “The Bible posits a God who builds,” says one commentary, and so “God is portrayed [in the Bible] as a master builder in His work of creation.”23 Proverbs 8:27 states that during the cycle of creation, God marked out a circle on the sea or the abyss, which not only ties this verse to chaos ideology but also implies that God — as depicted in Figure 14 — used a compass to draw the circular boundary for the chaotic waves of the sea.24

Figure 14: “When he prepared the heavens, I was there: when he set a compass upon the face of the depth” (Proverbs 8:27)

Just two verses later, in Proverbs 8:29, there is another reference to God’s creative activity: “I was there .… when [God] appointed (chaqaq — marked out) the foundations of the earth.” If this action is thought of in architectural terms, then a specific measuring instrument readily suggests itself. In ancient Egypt — Israel’s neighbor to the south — the foundation of a building would sometimes be marked out by first creating a base-line and then employing a set square in order to ensure that each of the foundation lines would be laid out at precise 90o angles.25

Finally, there is Job chapter 38, verse 5, to consider, where the Lord “describe[s] His creation of the earth as stretching out a line over it,” implying that “everything about the earth’s constitution was subject to His exact specifications.”26 Yet, it should also be remembered that in the context of kingly judgment, “God is depicted [in the Bible] as actively [Page 53]bringing chaos to bear on man’s rebellion … . Isaiah reveals God as the ‘builder’ of chaos: paradoxically, the Creator God will ‘stretch out the measuring line of chaos and the plumb line of destruction’ (Isaiah 34:11). Like many images of judgment,” says one author, “chaos is seen as a temporary reversal of the creation order.”27

Figure 15: Egyptian depiction of stretching out a line

Additional scriptural references show that what has just been discussed did not apply only to the Heavenly King but also to His earthly vice-regent as well. On the day when the earthly king received his initiation into office, he was told that his hand would be placed on the sea to conquer it, just as God had done (Psalm 89:9, 25), and the mortal sovereign was also given a scepter as part of his regalia (Psalms 2; 110). Other scriptures report that the earthly king laid the foundation of Israel’s temple (1 Kings 5:17; Ezra 6:3; Zechariah 4:9) and that he employed a measuring line while constructing it (Zechariah 4:9-10). Hence, all of the objects associated with the King of Heaven earlier in this paper can also be linked with the early king of Israel.

In addition, there are references from acknowledged kingship initiation texts demonstrating that on the day when the mortal king [Page 54]of Israel ascended the throne, he received the three attributes which were required for passage through the temple barriers: righteousness, uprightness, and truth. As previously mentioned in this study, it is known that these particular attributes can be identified with specific architectural tools:

Psalm 72:1-2: Give the king … O God … thy righteousness .… He shall judge thy people in righteousness.

Psalm 19:13: [God] keep [the king] … then shall [he] be upright (tamam; cf. Psalm 15 entrance liturgy).

Psalm 89:24 (cf. Psalm 101:7): [God’s] faithfulness (emunah = truth) … shall be with [the king].

Finally, there is 1 Kings 3:6 to contemplate:

And Solomon said, Thou hast shewed unto thy servant David my father great mercy, according as he walked before thee in truth, and in righteousness, and in uprightness of heart with thee.

Here it is confirmed that the king of Israel did, in reality, exemplify the three divine throne attributes which would enable a person to pass into the Lord’s presence in His temple throne room.

In summary, this chapter has endeavored to demonstrate that there is a hitherto unrecognized but detailed, matching pattern embedded within the Old and New Testaments. This pattern shows that the cubic Holy of Holies in the Israelite temple represented the heavenly throne room of the Heavenly King. This room had three guarded gateways which could be passed only by those who possessed three royal attributes which were, in turn, connected with specific liturgical actions and tools. These tools of architecture and measurement were also associated with kingship motifs of creation and conquering chaos, and on the day when a person was initiated as a king in ancient Israel, all of these concepts were applied to him. From a much broader perspective, the material in this paper also points to the fact that certain temple ideologies and actions were not abandoned by the Christians of the biblical period but were, in fact, perpetuated by them.

[Page 55]

In Luke 13:22–30 Jesus Christ speaks of obtaining salvation in the kingdom of God and links the attainment of such a state with passing through a gateway. If this entire block of verses in the book of Luke is compared with the 21st and 22nd chapters of the book of Revelation a clear set of parallels materializes. Since the chapters in Revelation are describing the heavenly New Jerusalem (which is the prototype for the Holy of Holies of the Israelite temple) it can be deduced that Luke 13:22–30 is referring to the same thing. Here are the fourteen correspondences between these biblical texts which make this deduction possible.

- Luke 13:22 – “Jerusalem”

- Revelation 21:2 – “new Jerusalem”

- Luke 13:23 – “Lord, are there few that be saved?”

- Revelation 21:24 – “them which are saved shall walk in [New Jerusalem]”

- Luke 13:24 – “enter in at the … gate”

- Revelation 22:14 – “enter in through the gates [of New Jerusalem]”

- Luke 13:24 – “many … will seek to enter in, and shall not be able”

- Revelation 21:12 – “at the gates [of New Jerusalem] … [there are] angels”1; Revelation 21:27 – “there shall in no wise enter into [New Jerusalem] any … but they which are written in the Lamb’s book of life”; Rev 22:14 – “they that do [God’s] commandments [i.e., the obedient] … may enter in through the gates”

- Luke 13:25 – “the master of the house … . Lord”

- Revelation 21:5 – “God himself shall be with them [in New Jerusalem]”

- Luke 13:25 – “is risen up, and hath shut to the door”

- Revelation 21:25 – “the gates of [New Jerusalem] shall not be shut”

- Luke 13:25 – “I know you not”

- Revelation 21:27 – “they which are written in the Lamb’s book of life [enter New Jerusalem]”

- Luke 13:26 – “We have eaten and drunk in thy presence”

- Revelation 22:1–2 – “a pure river of water of life … proceeding out of the throne [in New Jerusalem] … . and on either side of the river … [is] the tree of life, which bare[s] … fruits”

- Luke 13:26 – “thou hast taught in our streets”

- [Page 56]Revelation 22:2 – “the street of [New Jerusalem]”

- Luke 13:27 – “depart from me, all ye workers of iniquity”

- Revelation 21:27 – “there shall in no wise enter into [New Jerusalem] anything that defileth, neither whatsoever worketh abomination, or maketh a lie”

- Luke 13:28 – “there shall be weeping and gnashing of teeth”

- Revelation 21:4 – “there shall be no … sorrow, nor crying [in New Jerusalem]”

- Luke 13:28 – “ye shall see Abraham, and Isaac, and Jacob, and all the prophets, in the kingdom of God”

- Revelation 21:24 – “the kings of the earth do bring their glory and honor into [New Jerusalem]”

- Luke 13:29 – “they shall come from the east, and from the west, and from the north, and from the south”

- Revelation 21:13 – “On the east [side of New Jerusalem] three gates; on the north three gates; on the south three gates; and on the west three gates”

- Luke 13:30 – “there are first which shall be last”

- Revelation 22:13 – “I am … the first and the last”

Considering that in this paper Revelation 21:17 has been shown to reflect the Psalm 15 temple entrance liturgy, it may be profitable to more closely consider the liturgical entrance aspects of Luke 13:22–30. There is a narrow, closed gate; a guard stands on the gate; the attention of the gatekeeper is obtained by knocking at the gate; a request for entry through the gate is made; a conversation takes place between the gatekeeper and the person seeking entrance; entry requirements are indicated by the gatekeeper; entrance is granted only if the entry requirements are met.

Since Luke 13 and Revelation 21 are Christian documents it is also noteworthy that some of the early Christians incorporated the Psalm 24 temple entrance text and the act of knocking into their ascension ideology and gateway liturgies.

The second century Christian writers Justin Martyr28 (ca. ad 150) and Irenaeus29 (ca. ad 185) applied the phraseology of Psalm 24:7–10 to Jesus Christ’s ascent into heaven after He had been resurrected from the dead. And they both specified that the Savior entered heaven through its gates. This psalm would have held a place of great significance among the early Christians since it had been recited in the courts of the Israelite temple on the very day that Jesus Christ arose from the tomb.30

At some point in time the questions and answers associated with Psalm 24:7–10 were incorporated as a liturgical element in some of the [Page 57]early Christians’ church dedication rites.31 This incorporation can be detected on 24 December 526 when the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople was rededicated. On this occasion a procession of the faithful sang Psalm 24 as the patriarch (holding a copy of the Gospels as a representation of Jesus Christ) passed through the doors.32 One liturgist has pointed out that this ceremony fulfilled, “even if only symbolically, the ancient liturgy of entrance into the temple.”33 Paul the Silentiary (d. ad 575–580), who was an imperial officer in Emperor Justinian’s palace, spoke of the Sanctuary or Holy of Holies area of the Hagia Sophia in this way: “the screen gives access to the priests through three doors.”34 This architectural arrangement is reminiscent of the three gateways on the east side of the Holy of Holies of the Israelite Tabernacle and also the three gates on each side of the New Jerusalem-Holy of Holies cube.35

In the records of subsequent dedication ceremonies the element of knocking on the church door is found coupled together with the questions and answers found in Psalm 24:7–10. The Gallican dedicatory ritual in France “at the beginning of the eighth century” records some of the points of drama that took place. A lone cleric would be shut up on the inside of the church; the bishop approached the door; the bishop then said the Psalm 24:7–10 antiphon while touching the lintel of the structure; while a similar psalm was being chanted, the door was opened and the bishop entered.36 One commentator on the 8th century Gallican rite says that once the procession “reaches the entrance to the church … the bishop strikes the sill three times with his staff and orders the doors to be opened,” and the procession continues through the entryway.37

The triple striking of the door and the interrogatories and responses of Psalm 24 are present in Christian church dedication documents of the mid-tenth century38 and continue to be found throughout the Middle Ages.39 One important clue about the meaning of all this can be found in the writings of Hugh of St. Victor. He stated that during the dedication ordinance, the bishop represented Jesus Christ, and it was he who enacted “the threefold striking of the lintel of the main door.”40 Thus, we are brought back to the idea put forward by Justin Martyr and Irenaeus, in much earlier times, that Psalm 24:7–10 was associated with Christ’s ascent through the gates of heaven, or the heavenly Jerusalem.

Figure Credits

- The Holy Place and the Holy of Holies of the Tabernacle. http://www.templebuilders.com/enlargement_tabernacle5.php.

- [Page 58]Charles F. Horne and Julius A. Bewer, eds., The Bible and Its Story Taught by One Thousand Picture Lessons (New York: Francis R. Niglutsch, 1908), vol. 2. http://www.wcg.org/images/b2/_0303160501_039.jpg (accessed 2 October 2014).

- Rendered by Jeffrey M. Bradshaw after a concept by Matthew B. Brown. Image: J. James Tissot, 1836-1902: The Ark of the Covenant, ca. 1896-1902. In J. James Tissot. The Old Testament: Three Hundred and Ninety-Six Compositions Illustrating the Old Testament, Parts 1 and 2. 2 vols. Paris, France: M. de Brunhoff, 1904, 1:229.

- Rendered by Jeffrey M. Bradshaw after a concept by Matthew B. Brown. Image: J. James Tissot, 1836-1902: The Ark of the Covenant, ca. 1896-1902. In J. James Tissot. The Old Testament: Three Hundred and Ninety-Six Compositions Illustrating the Old Testament, Parts 1 and 2. 2 vols. Paris, France: M. de Brunhoff, 1904, 1:229.

- Rendered by Jeffrey M. Bradshaw after a concept by Matthew B. Brown. Image: James Harpur, ed., Great Events of Bible Times (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1987), 44–45.

- Bishop knocking three times on a cathedral door. http://www.antigonishdiocese.com/BishopDunnsInstallationAsBishopofAntigonish/theritualbegins.html (accessed 2 October 2014).

- Egyptian merkhet (plumb) line. https://www.ssplprints.com/image/94993/scm-photo-studio-egyptian-star-clock-merkhet-c-600-bc (accessed 2 October 2014).

- Egyptian leveling line. http://www.touregypt.net/featurestories/tomb.htm (accessed 2 October 2014).

- Image from the J. Paul Getty Museum, French, ca. ad 1400. http://www.getty.edu/art/gettyguide/artObjectDetails?artobj=1666&handle=li (accessed 2 October 2014).

- Rendered by Jeffrey M. Bradshaw after a chart by Matthew B. Brown.

- Rendered by Jeffrey M. Bradshaw after a chart by Matthew B. Brown.

- Charles F. Horne and Julius A. Bewer, eds., The Bible and its Story Taught by One Thousand Picture Lessons (New York: Francis R. Niglutsch, 1908), vol. 8. http://www.gci.org/files/images/b8/b8a%20%288%29.jpg (accessed 2 October 2014).

- Rendered by Jeffrey M. Bradshaw after a concept by Matthew B. Brown. Image by Gabriel Fink, Wikipedia. [Page 59]http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Temple-of-Solomon-Exterior.jpg (accessed 2 October 2014).

- Photograph by Matthew B. Brown.

- Egyptian stonemason with measuring line, New York Public Library.

Go here to see the one thought on ““Cube, Gate, and Measuring Tools: A Biblical Pattern”” or to comment on it.