[Page 1]Abstract: For Latter-day Saints, the critical scholarly consensus that most of the book of Isaiah was not authored by Isaiah often presents a problem, particularly since many Isaiah passages in the Book of Mormon are assigned post-exilic dating by critical scholars. The critical position is based on an entirely different set of assumptions than most believers are accustomed to bring to scripture. This article surveys some of the reasons for the critical scholarly position, also providing an alternative set of assumptions that Latter-day Saints can use to understand the features of the text.

I have a tradition from my grandfather’s house that the same communication is revealed to many prophets, but no two prophesy in the identical phraseology.

—Babylonian Talmud, Sanhedrin 89a

When presented with the critical scholarly consensus that the Book of Isaiah was written and compiled by multiple authors and redactors over a period of time that stretches into the post-exilic period of ancient Israelite history, our reflexive response as Latter-day Saints is often to adopt a defensive posture and dismiss the critical scholarly consensus. The obvious reason for this response is that the Book of Mormon contains writings that critical scholars believe were written, redacted, and incorporated into the Isaianic corpus of writings after the time Lehi left Jerusalem. To accept the multiple-Isaiah theory, then, requires a believing Mormon to adopt any number of creative thought [Page 2]processes to explain how Lehi’s party arrived in the Americas with scriptures that had not yet been produced.

Assumptions

In discussing the multi-author theory, I think I should begin by stating the assumptions I bring to scripture. First, I have what might be termed liberal views of scripture: I believe the Lord’s directive to Oliver Cowdery in Doctrine and Covenants 9:8 to “study out” scripture in his mind before writing represents a model of scriptural development that utilizes the author’s own mental and intellectual resources. This helps to explain the vast discrepancies in style, content, and rhetorical approach found in scriptures produced by prophets operating as contemporaries in the same political and cultural circumstances. The uncomfortable possibility that this model of scriptural development presents to the orthodox or inerrantist believer is the intrusion of the author’s own worldview into the process, resulting in scriptural narratives that include such features as ancient Near Eastern cosmology or outdated, unproductive notions of race or gender.

Second, I also hold conservative religious views of scripture: I believe God does use scripture as a vehicle to advance our understanding of His purposes and His dealings with humanity, and I also believe scripture often provides a reliable view of future events before they come to pass.

Third, I believe the Book of Mormon is what its introduction claims it to be: “a record of God’s dealings with ancient inhabitants of the Americas.” I believe in the book’s origin story of angels, plates, prophetic gifts, and translation/transmission that occurred by the “gift and power of God.”1

Fourth and finally, I accept the basic critical scholarly view that Isaiah of Jerusalem is not the author of all the text attributed to him in the book of Isaiah. However, I reject the three-part division of the book that has been used by critical scholars since the emergence of Bernhard Duhm’s 1892 study,2 which has provided the foundation for most studies that assert a three-part division of the book.3

Stating the Problem Accurately

I have often seen LDS commentators frame the Book of Mormon’s “Isaiah problem” as some form of the following: In the book of Isaiah, scholars only attribute the first 39 chapters to Isaiah of Jerusalem, and attribute the remainder of the book to post-exilic authors whose contributions could not have been available on the Brass Plates that Lehi’s family brought to [Page 3]the New World from Jerusalem.4 This is a simple summary of what is in fact a very complex scholarly position. In the Yale Anchor Bible Isaiah commentary, for example, the three volumes of the commentary are divided into the traditional critical scholarly division of chapters 1–39 (vol. 1), 40–55 (vol. 2), and 56–66 (vol. 3). In volume 1 of the commentary, representing chapters 1–39, Isaian authorship is contested for most chapters, either as a whole or in part. There are many reasons for this, and I will discuss some of these reasons further along in this article.

I believe it extremely important to state our “Isaiah problem” as accurately as possible. My attempt to do so results in a three-part statement:

- Among critical scholars of the Bible, there has emerged a consensus that the book of Isaiah contains significant amounts of material that cannot be reliably attributed to Isaiah of Jerusalem. This consensus is the result of scholars’ observations of changes in authorial tone, linguistic features, anachronisms, and other textual elements that cannot be accounted for by

- Changes in Isaiah’s religious and political perspective over a prophetic career spanning 40+ years,

- Different audiences for the various prophetic narratives and oracles, and

- Centuries of reproduction and redaction of the text.

- The Book of Mormon contains material from Deutero Isaiah, particularly chapters 48–53, that critical scholars attribute to post-exilic authors. If the critical scholarly position is valid, this would imply that these chapters could not have been included in the Brass Plates and would have been unavailable to Lehi’s party.

- Latter-day Saints have not yet developed robust theoretical frameworks for assessing the findings of critical Biblical scholarship and integrating these findings, where necessary, into our narratives regarding the production and transmission of scripture. This has resulted in responses to critical scholarship that are inadequate in the face of the evidence that emerges from critical analysis of Biblical texts.

My discussion of this problem will frequently be personal in tone because scripture in general, and the book of Isaiah in particular, [Page 4]inform my deepest religious convictions. However, as I proceed through discussion of the problem and some possible responses to it, it will become clear that I believe few if any scholarly stakeholders in the questions of authorship of the book of Isaiah are approaching the text from a dispassionate or logically consistent point of view and that both the conservative/devotional and the liberal/critical positions are characterized by significant blind spots that undermine the soundness of their positions.

The Reasons for the Critical Scholarly Position

In Eerdman’s commentary on Isaiah 1–39, Marvin Sweeney summarizes Duhm’s three-part division of the book:

During most of the 20th Century, it has been customary to treat Isaiah 1–39 as a distinct prophetic book. This is based on the historical presuppositions that stand behind Duhm’s identification of First, Second, and Third Isaiah within the book as a whole. Duhm’s paradigm holds that chs. 1–39 must be associated with the 8th-century prophet, Isaiah ben Amoz; that chs. 40–55 are the work of an anonymous prophet of the Babylonian exile identified only as Deutero-Isaiah; and that chs. 56–66 reflect the work of a postexilic prophet identified as Trito-Isaiah.5

Sweeney presents some of the thinking scholars employ in support of late authorship for deutero-Isaiah:

Second Isaiah displays a number of concerns that point to a context in late 6th-century Babylonia at the time of the submission of the city to King Cyrus of Persia. Of course, the first indication of this concern is the identification of Cyrus as YHWH’s messiah and temple-builder in 44:28 and 45:16

As the famed Cyrus Cylinder indicates, the outset of Cyrus’s reign as Babylon’s new monarch saw his decree that the various nations that had been exiled by the Babylonians could return to their homelands with their gods and reestablish their temples while maintaining loyalty to Cyrus and the Persian Empire. … Although Judah is not mentioned in the Cyrus Cylinder, Cyrus’s decree to allow Jews to return to Jerusalem to rebuild the temple is in keeping with the announcement recorded in the Cyrus Cylinder.7

[Page 5]The prophet’s political shift from David to Cyrus likewise points to a Babylonian setting for chs. 40–55.8

Cyrus was proclaimed king of Babylon at the Akitu festival of 539, and it is likely that Deutero-Isaiah’s images from Isaiah 46 represent an eyewitness account of that event.9

The use of the term ḥārēd, “he who trembles,” to refer to those who observe the covenant as “those who tremble” (ḥărēdîm) at the word of YHWH also points to the interrelationship between Isaiah and Ezra-Nehemiah … Apart from 1 Sam 4:13, these are the only occurrences of this term in the Hebrew Bible.10

In addition, critical scholars employ other evidence in determining later dating for Isaiah texts. An example would be the presence of language and theological concepts utilized by the Deuteronomist school of historians and redactors, whose influence on the Biblical text is often dated to a period of time during and following Josiah’s reign. Joseph Blenkinsopp, for example, uses as evidence for later authorship of Isaiah 44 the fact that “the sobriquet Jeshurun for Israel the Chosen … appears only in the Deuteronomic poems (Deut 32:15; 33:5; 26) and in Second Isaiah (Isa 44:2).”11

The common use of pseudonymous authorship in ancient sacred texts provides a basis for scholars to conceptualize additional authors for texts such as the book of Isaiah. This phenomenon of pseudepigrapha was common in the ancient world, where concepts of plagiarism and misattribution of texts did not carry the same level of negative stigma they do in modern times. Anciently, it was common practice for authors to attribute their work to a different, more prominent historical figure in order to increase its audience and enhance its status.12 The pervasiveness of this practice in the Biblical era has led scholars to conclude that pseudonymous authorship and misattribution have explanatory power for many of the inconsistencies and anachronisms that characterize Biblical writings.

One of the more controversial aspects of the critical scholarly perspective on dating of texts is that scholars assign later dates to texts based upon the presence of predictive prophecy in the text. Critical scholars are correct to point out that this is only one of many factors they consider when attempting to assign a production time frame to a text; however, conservative scholars are also correct to point out that the [Page 6]rejection of predictive prophecy is extremely pervasive in critical studies, and it serves to color how critical scholars select, evaluate, and prioritize all the other evidence they consider in questions of authorship. Some typical examples of dating based on rejection of predictive prophecy include the following:

The date of composition [of Isaiah 13] cannot be fixed for certain. That it is not directed against the Assyrians as rulers of Babylon and therefore does not come from the lifetime of Isaiah can be deduced from the prominence given to the Medes … The final verses have led several commentators to conclude that the poem is predictive of an event to take place in the near future, and must therefore have been composed shortly before the fall of Babylon in 539 bce13

Since [Isaiah 14:1–2] refers to the return from Exile and the conversion of pagan nations, it has affinities with the second part of Isaiah, namely, chs. 40–55, and perhaps its date of composition is the same.14

[Isaiah 21:1–10] was written by an anonymous prophet, active at the time of Babylon’s fall in 539 bce15

Though the dating of the three oracles in Isaiah 21 is disputed … the more dominant view today tends to put the oracles later, usually in the period of the Babylonian exile … The dating to the period of the Babylonian exile is largely based on the mention of the fall of Babylon in v.9 and the assumed role of the Medes and Elamites in this event.16

The Latter-day Saint Response

The critical scholarly consensus concerning the production of the book of Isaiah transforms Isaiah of Jerusalem from the towering, enormously influential prophetic figure revered by Lehi’s descendants and the writers of the Gospels into a figure who produced very little original material over 40+ years of ministry but whose body of work was, for some reason, expanded by possibly more than 200% over time by the work of pseudonymous authors and redactors operating over a period of centuries.

In the face of this challenge to our understanding of Isaiah, the apologetic instinct is to counter the critical consensus with arguments for unity of the text based on statistical analysis17 or reiteration of facts such [Page 7]as that the book of Isaiah has always been found as currently arranged. A middle ground may have been sketched by Hugh Nibley when he asked, “Can it be that [Isaiah chapters 2–14 and 48–54] represent what pretty well was the writing of Isaiah in Lehi’s time?”18 While I think the apologetic arguments deserve to be taken seriously, I also believe that often the apologetic impulse can lead believers to ignore more productive approaches.

A Theory for a Theory

The multiple-Isaiah theory has been the dominant view of critical scholars for more than a century. Since its inception, the theory has been supported by the intellectual scaffolding of countless studies, and its influence has rippled out to influence the ways scholars assess the authorship of other Biblical books, such as Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and others. Just as important, however, is the way the multiple-Isaiah theory influences scholarly perspectives on the dating of the earlier chapters of the book. Consider, for example, this discussion of Isaiah 2 from the Anchor Bible commentary:

Picking our way through the editorial debris that has gradually accumulated in this passage … we discern the outline of a poem on Judgment Day composed, typically, of indictment (6–8) and verdict (12–16). One of the most obvious additions to this poetic core occurs at the end of the indictment (“to the work of their hands they bow down, to that which their fingers have made,” 8b), being an example of standard anti-idolatry polemic of a kind frequently encountered in the second part of the book (40:18–20; 45:20), probably therefore from the late Neo-Babylonian or early Persian period.19

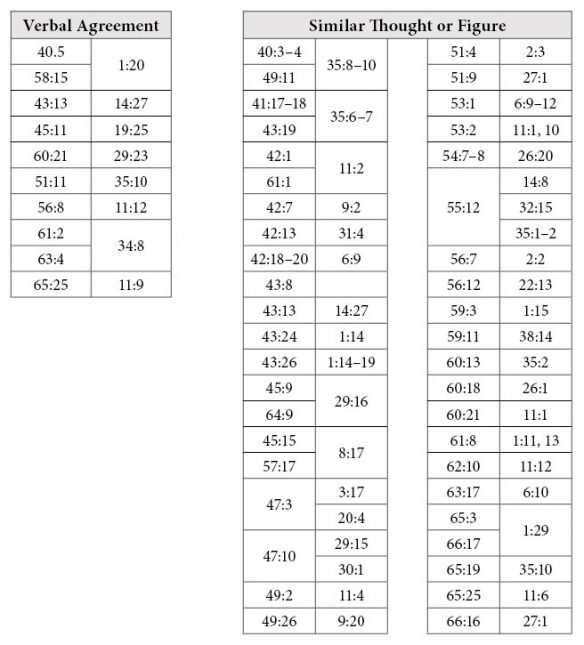

Some of the assumptions supporting this theory are very sound, but other elements of support for the theory are based on subjective judgment calls and conflicting views on nontrivial matters, such as the amount of thematic correspondence between different sections of the book. This discussion of thematic correspondence and textual similarities is a debate that has been underway for more than a century. A typical argument for similarity is found in the list of correspondences detailed in John Howard Raven’s 1906 book Old Testament Introduction: General and Special:20

Blenkinsopp’s response to these arguments for linguistic and thematic similarity is representative of the critical position:

Several recent commentators have convinced themselves of close editorial or compositional connections between 1–39 and 40–66 on the basis of motifs or turns of phrase that appear throughout both major sections, but on the whole the differences are more in evidence than the similarities.21

In addition to these textual arguments, the studies arguing for multiple authorship are themselves buttressed by meta-studies that debate whether scholarly inquiry is properly weighing and evaluating evidence and whether tools for analyzing the text are being properly used. Over more than a century’s time, the theory has evolved from an [Page 9]educated hunch into a massive scholarly ecosystem that best explains to critical scholars the textual and thematic features of the book of Isaiah, as well as its relationship to other books of the Bible.

For Latter-day Saints to engage the critical scholarly enterprise in defense of a model of Isaianic unity would be fruitless for two reasons. First, Latter-day Saint scholars bring very different assumptions to their analysis of scripture than do critical scholars and even believing, conservative scholars of other faith traditions. For example, the Latter day Saint religious tradition brings ample resources to assume the following:

- Predictive prophecy is a real phenomenon.

- A prophet’s perspective can change in very significant ways in response to new information and continued revelation. The likelihood of this is high when a prophetic career spans multiple decades.

- A significant level of change and revision to the Biblical text has occurred over centuries of transmission.

Second, most Latter-day Saint scholars who are familiar with critical scholarship are not likely to defend a pure conservative position that the book was authored, word for word, by Isaiah of Jerusalem. The appropriate Latter-day Saint response to the multiple-Isaiah theory, then, is not to respond with a scholarly turf war over authorship of discrete sections of text in the book of Isaiah, such as whether a given set of verses show evidence of redaction or the gloss of authentic Isaianic material versus different authorship. The most productive response, I believe, would be the development of a uniquely Mormon theory of development of scripture, of which the authorship of Isaiah would be only a part.

The Role of the Book of Mormon

The Book of Mormon’s use of Isaiah begins with Nephi’s reprinting of Isaiah 48, a prophetic salvo asserting the reality and purpose of predictive prophecy in Isaiah’s ministry:

3 Behold, I have declared the former things from the beginning; and they went forth out of my mouth, and I showed them. I did show them suddenly.

4 And I did it because I knew that thou art obstinate, and thy neck is an iron sinew, and thy brow brass;

[Page 10]5 And I have even from the beginning declared to thee; before it came to pass I showed them thee; and I showed them for fear lest thou shouldst say — Mine idol hath done them, and my graven image, and my molten image hath commanded them.

6 Thou hast seen and heard all this; and will ye not declare them? And that I have showed thee new things from this time, even hidden things, and thou didst not know them.

7 They are created now, and not from the beginning, even before the day when thou heardest them not they were declared unto thee, lest thou shouldst say — Behold I knew them. (1 Nephi 20:3–7)

While the use of Isaiah 48 in early Nephite scripture would be considered anachronistic by critical scholars, there are other chapters of the Biblical Isaiah, such as chapters 1 and the 36–39 history, that critical scholars consider to be post-exilic and are not found in the Book of Mormon.

Hugh Nibley’s conjecture that the Book of Mormon may serve as an indicator of the state of the text of Isaiah at the time of Lehi implies that a believer can use the Book of Mormon as an authoritative boundary for the findings of critical scholarship. The obvious problem with this approach is that it might imply that the Book of Mormon is a reliable guide as to which Biblical scriptures are pre-exilic and which are post exilic. This is not a capability the Book of Mormon claims for itself.

The Book of Mormon contains several examples of post-exilic scriptural language; this often poses a problem for believers due to the assumption most believers bring to the text that Joseph Smith’s own mental resources — including scriptural language he had internalized from years of reading and discussing the Bible — had no role or influence in the transmission of the ideas contained in the plates of brass. One of many examples of Book of Mormon text that seems to reflect Joseph’s affinity for Biblical language would be 2 Nephi 4:17, where the phrase “Oh wretched man that I am!” is the same used by Paul in Romans 7:24: “O wretched man that I am! who shall deliver me from the body of this death?” Another example is 2 Nephi 26, which includes language from Malachi 4.

Refuting the notion of absolute originality in scriptural authorship, the Book of Mormon itself presents examples of prophetic language borrowed from other prophetic language. In The Book of Mormon: A [Page 11]Reader’s Edition, Grant Hardy demonstrates, through his use of italics in 2 Nephi 26, how Nephi seemed to be greatly influenced by the words of Isaiah and effortlessly borrowed from the language of Isaiah 29 in prophesying for his own people:

After my seed and the seed of my brethren shall have dwindled in unbelief, and shall have been smitten by the Gentiles; yea, after the Lord God shall have camped against them round about, and shall have laid siege against them with a mount, and raised forts against them; and after they shall have been brought down low in the dust, even that they are not, yet the words of the righteous shall be written, and the prayers of the faithful shall be heard, and all those who have dwindled in unbelief shall not be forgotten. For those who shall be destroyed shall speak unto them out of the ground, and their speech shall be low out of the dust, and their voice shall be as one that hath a familiar spirit; for the Lord God will give unto him power, that he may whisper concerning them, even as it were out of the ground; and their speech shall whisper out of the dust. For thus saith the Lord God, “They shall write the things which shall be done among them, and they shall be written and sealed up in a book, and those who have dwindled in unbelief shall not have them, for they seek to destroy the things of God.” Wherefore, as those who have been destroyed have been destroyed speedily; and the multitude of their terrible ones shall be as chaff that passeth away — “yea,” thus saith the Lord God, “it shall be at an instant, suddenly” — And it shall come to pass, that those who have dwindled in unbelief shall be smitten by the hand of the Gentiles.22

Nephi provides yet another example of borrowing, as he is the only Book of Mormon author to utilize Jeremiah’s teaching, “Cursed be the man that trusteth in man, and maketh flesh his arm, and whose heart departeth from the Lord” (Jeremiah 17:5). Nephi uses Jeremiah’s phraseology in 2 Nephi 4:34, where he says “I know that cursed is he that putteth his trust in the arm of flesh. Yea, cursed is he that putteth his trust in man or maketh flesh his arm” and again in 2 Nephi 28:31, saying, “Cursed is he that putteth his trust in man, or maketh flesh his arm … ”

In neither of these examples does Nephi see fit to delineate exactly which of his writings have origin in his own mental and spiritual [Page 12]processes and which reflect the influences of his prophetic forebears and peers. In this sense, Nephi’s approach to the development of scripture is reflective of what he must have been exposed to in his own study of scripture, as the books of the Old Testament are replete with examples of prophetic and scribal borrowing, repurposing, and expansion of other texts.23

An example from the Old Testament is found in the pronouncement of woes against the pastors and shepherds (religious and political leaders) of Judah, found in the books of Jeremiah and Ezekiel:

|

Jeremiah 23 |

Ezekiel 34 |

| 1 Woe be unto the pastors that destroy and scatter the sheep of my pasture! saith the Lord.

2 Therefore thus saith the Lord God of Israel against the pastors that feed my people; Ye have scattered my flock, and driven them away, and have not visited them: behold, I will visit upon you the evil of your doings, saith the Lord. 3 And I will gather the remnant of my flock out of all countries whither I have driven them, and will bring them again to their folds; and they shall be fruitful and increase. 4 And I will set up shepherds over them which shall feed them: and they shall fear no more, nor be dismayed, neither shall they be lacking, saith the Lord. 5 ¶Behold, the days come, saith the Lord, that I will raise unto David a righteous Branch, and a King shall reign and prosper, and shall execute judgment and justice in the earth 6 In his days Judah shall be saved, and Israel shall dwell safely: and this is his name whereby he shall be called, The Lord Our Righteousness. 7 Therefore, behold, the days come, saith the Lord, that they shall no more say, The Lord liveth, which brought up the children of Israel out of the land of Egypt; |

2 Son of man, prophesy against the shepherds of Israel, prophesy, and say unto them, Thus saith the Lord God unto the shepherds; Woe be to the shepherds of Israel that do feed themselves! should not the shepherds feed the flocks?

5 And they were scattered, because there is no shepherd: and they became meat to all the beasts of the field, when they were scattered. 11 ¶For thus saith the Lord God; Behold, I, even I, will both search my sheep, and seek them out. 12 As a shepherd seeketh out his flock in the day that he is among his sheep that are scattered; so will I seek out my sheep, and will deliver them out of all places where they have been scattered in the cloudy and dark day. 13 And I will bring them out from the people, and gather them from the countries, and will bring them to their own land, and feed them upon the mountains of Israel by the rivers, and in all the inhabited places of the country. 15 I will feed my flock, and I will cause them to lie down, saith the Lord God. 16 I will seek that which was lost, and bring again that which was driven away, and will bind up that which was broken, and will strengthen that which was sick: but I will destroy the fat and the strong; I will feed them with judgment. |

| 8 [Page 13]But, The Lord liveth, which brought up and which led the seed of the house of Israel out of the north country, and from all countries whither I had driven them; and they shall dwell in their own land. | 23 And I will set up one shepherd over them, and he shall feed them, even my servant David; he shall feed them, and he shall be their shepherd.

24 And I the Lord will be their God, and my servant David a prince among them; I the Lord have spoken it. |

Using dates of composition to determine any kind of direction in borrowing is complicated in this instance by the fact that Jeremiah and Ezekiel were contemporaries. Jack Lundbom says of Jeremiah 23:

The view of some scholars (Cornill; Volz; Rudolph; Mendecki 1983) that v3 is an exilic or postexilic gloss owing to its inspiration to Ezekiel 34 should be rejected. The verse is entirely consistent with the thought of Jeremiah and fits in well with v4. Lust (1981:126) also points out that “gathering and return,” which figures prominently in Jeremiah (and Ezekiel) is not a “Deuteronomistic” idea. Nothing in any of these oracles requires a post-586 bc date, a setting other than Jerusalem, or an attribution to someone other than Jeremiah.24

Moshe Greenberg agrees: “The influence of Jeremiah, both in the image and in the terminology, on both components of this oracle is patent. It is plausibly accounted for by the assumption that Ezekiel had access to the words of his older Jerusalemite contemporary.”25

A more striking, commonly-cited Old Testament example of these textual similarities is found in the language of Isaiah 2 and Micah 4:

|

Isaiah 2 |

Micah 4 |

| 2 And it shall come to pass in the last days, that the mountain of the Lord’s house shall be established in the top of the mountains, and shall be exalted above the hills; and all nations shall flow unto it. | 1 But in the last days it shall come to pass, that the mountain of the house of the Lord shall be established in the top of the mountains, and it shall be exalted above the hills; and people shall flow unto it. |

|

Isaiah 2 |

Micah 4 |

| 3 [Page 14]And many people shall go and say, Come ye, and let us go up to the mountain of the Lord, to the house of the God of Jacob; and he will teach us of his ways, and we will walk in his paths: for out of Zion shall go forth the law, and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem.

4 And he shall judge among the nations, and shall rebuke many people: and they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruninghooks: nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more. |

2 And many nations shall come, and say, Come, and let us go up to the mountain of the Lord, and to the house of the God of Jacob; and he will teach us of his ways, and we will walk in his paths: for the law shall go forth of Zion, and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem.

3 ¶And he shall judge among many people, and rebuke strong nations afar off; and they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruninghooks: nation shall not lift up a sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more. |

The superscription in Isaiah 2:1 claims that the verses to follow represent “The word that Isaiah the son of Amoz saw concerning Judah and Jerusalem,” whereas Micah 4 makes no such claim. As a believer, I cannot reject outright the possibility that God revealed similar language to these two prophets; however, this position is complicated by the fact that after these similar verses, Isaiah 2 and Micah 4 diverge sharply in their content. The two chapters are dissimilar except for these three verses. Blenkinsopp says of these verses, “Every possible explanation of this duplication has been given at one time or another … In this instance certainty is unattainable, but it seems the complex topoi represented in the passage is more at home in Isaiah than Micah.”26 Schultz also notes that most scholars recognize a number of less extensive parallels between Isaiah and Micah:

|

Micah |

Isaiah |

Micah |

Isaiah |

|||

|

1:11 2:13 3:5 3:8 3:11 4:7 4:9 4:13 |

<-> <-> <-> <-> <-> <-> <-> <-> |

47:2–3

52.12 56.10–11 58.1 48.2 24.24 13:8, 21:3 41:15–16, 23:18 |

5:5 5:13 6:7 6.8 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.17 |

<-> <-> <-> <-> <-> <-> <-> <-> |

9.6

2.8 1.11 1.17 24:13 57:1 1:23 49:23 |

The obvious problem here for adherents to the deutero-Isaiah theory is that these parallels are between prophetic contemporaries, and the aforementioned passages from Isaiah 2 and Micah 4 strongly suggest [Page 15]some interaction between these two. Most of these less-extensive parallels consist of verses that scholars consider to be written by someone other than Micah or Isaiah.27

Isaiah and Jeremiah

The Oracles Against Nations (OAN) are a series of prophecies against the nations surrounding Israel, and they are found in several prophetic books. The correspondence between OAN passages in Isaiah and Jeremiah is strong enough to suggest that, like Nephi, Jeremiah’s thinking was heavily influenced by the writings of Isaiah. Isaiah 13, 14, and 21 contain oracles against Babylon, which many scholars find anachronistic.

The Jewish Study Bible:

[Isaiah 13] assumes that Babylonia, rather than Assyria, is the world power. It must, therefore, have been addressed to an exilic audience in the mid-6th c., not to the 8th c. audience of Isaiah son of Amoz.28

The Oxford Study Bible:

Since Babylon did not develop into a ruling power until 612 bce when it destroyed Nineveh, the capital of Assyria, this oracle is probably later than Isaiah.29

The assumption in these statements seems to be that a prophet would not produce oracles against a nation that is not the “world power,” but there are many examples to the contrary. Isaiah’s OAN utterances are directed at Moab (Ch. 15), Damascus (Ch. 17), Egypt (Ch. 19), Arabia (Ch.21:11–17), Tyre and Sidon (Ch. 23), and Edom (Ch. 34). Although each of these nations posed a threat to Israel at one point or another, the geopolitical status of these various lands seems to have had no bearing whatsoever on the appropriateness of their targeting for prophetic warnings of destruction. Jeremiah’s and Ezekiel’s oracles are against similarly diverse groups of lands.

The following represent some examples of similar language between the oracles of Isaiah and Jeremiah, to an extent that suggests literary and rhetorical influence:[Page 16]

War Coming from the North

|

Isaiah |

Jeremiah |

| 14:31 Howl, O gate; cry, O city; thou, whole Palestina, art dissolved: for there shall come from the north a smoke, and none shall be alone in his appointed times.

41:25 I have raised up one from the north, and he shall come: from the rising of the sun shall he call upon my name: and he shall come upon princes as upon mortar, and as the potter treadeth clay. |

1:14 Then the Lord said unto me, Out of the north an evil shall break forth upon all the inhabitants of the land.

15 For, lo, I will call all the families of the kingdoms of the north, saith the Lord; and they shall come, and they shall set every one his throne at the entering of the gates of Jerusalem, and against all the walls thereof round about, and against all the cities of Judah. 6:22 Thus saith the Lord, Behold, a people cometh from the north country, and a great nation shall be raised from the sides of the earth. 23 They shall lay hold on bow and spear; they are cruel, and have no mercy; their voice roareth like the sea; and they ride upon horses, set in array as men for war against thee, O daughter of Zion. 50:3 For out of the north there cometh up a nation against her, which shall make her land desolate, and none shall dwell therein: they shall remove, they shall depart, both man and beast. 41 Behold, a people shall come from the north, and a great nation, and many kings shall be raised up from the coasts of the earth. 42 They shall hold the bow and the lance: they are cruel, and will not shew mercy: their voice shall roar like the sea, and they shall ride upon horses, every one put in array, like a man to the battle, against thee, O daughter of Babylon. |

Flee Babylon

|

Isaiah |

Jeremiah |

| 48:20 ¶Go ye forth of Babylon, flee ye from the Chaldeans, with a voice of singing declare ye, tell this, utter it even to the end of the earth; say ye, The Lord hath redeemed his servant Jacob. | 50:8 Remove out of the midst of Babylon, and go forth out of the land of the Chaldeans, and be as the he goats before the flocks.

51:6 Flee out of the midst of Babylon, and deliver every man his soul: be not cut off in her iniquity; for this is the time of the Lord’s vengeance; he will render unto her a recompence. |

The Medes

|

Isaiah |

Jeremiah |

| 14:17 Behold, I will stir up the Medes against them, which shall not regard silver; and as for gold, they shall not delight in it. | 51:11 Make bright the arrows; gather the shields: the Lord hath raised up the spirit of the kings of the Medes: for his device is against Babylon, to destroy it; because it is the vengeance of the Lord, the vengeance of his temple. |

[Page 17]

Fanning / Threshing

|

Isaiah |

Jeremiah |

| 21:10 O my threshing, and the corn of my floor: that which I have heard of the Lord of hosts, the God of Israel, have I declared unto you.

41:15 Behold, I will make thee a new sharp threshing instrument having teeth: thou shalt thresh the mountains, and beat them small, and shalt make the hills as chaff. 16 Thou shalt fan them, and the wind shall carry them away, and the whirlwind shall scatter them: and thou shalt rejoice in the Lord, and shalt glory in the Holy One of Israel. |

51:2 And will send unto Babylon fanners, that shall fan her, and shall empty her land: for in the day of trouble they shall be against her round about.

33 For thus saith the Lord of hosts, the God of Israel; The daughter of Babylon is like a threshingfloor, it is time to thresh her: yet a little while, and the time of her harvest shall come. |

Taunt (Babylon)

|

Isaiah |

Jeremiah |

| 14:4 … How hath the oppressor ceased! the golden city ceased!

6 He who smote the people in wrath with a continual stroke, he that ruled the nations in anger, is persecuted, and none hindereth. 14 … how art thou cut down to the ground, which didst weaken the nations! 21 Babylon is fallen, is fallen! — Other nations also are destroyed. |

50:23 How is the hammer of the whole earth cut asunder and broken! how is Babylon become a desolation among the nations!

51:41 How is Sheshach taken! and how is the praise of the whole earth surprised! how is Babylon become an astonishment among the nations! |

Babylon to be Desolate Except for Wild Beasts

|

Isaiah |

Jeremiah |

| 13:19 ¶And Babylon, the glory of kingdoms, the beauty of the Chaldees’ excellency, shall be as when God overthrew Sodom and Gomorrah.

20 It shall never be inhabited, neither shall it be dwelt in from generation to generation: neither shall the Arabian pitch tent there; neither shall the shepherds make their fold there. |

50:39 Therefore the wild beasts of the desert with the wild beasts of the islands shall dwell there, and the owls shall dwell therein: and it shall be no more inhabited for ever; neither shall it be dwelt in from generation to generation.

40 As God overthrew Sodom and Gomorrah and the neighbour cities thereof, saith the Lord; so shall no man abide there, neither shall any son of man dwell therein. |

| 21 [Page 18]But wild beasts of the desert shall lie there; and their houses shall be full of doleful creatures; and owls shall dwell there, and satyrs shall dance there.

22 And the wild beasts of the islands shall cry in their desolate houses, and dragons in their pleasant palaces: and her time is near to come, and her days shall not be prolonged. |

51:29 And the land shall tremble and sorrow: for every purpose of the Lord shall be performed against Babylon, to make the land of Babylon a desolation without an inhabitant.

37 And Babylon shall become heaps, a dwellingplace for dragons, an astonishment, and an hissing, without an inhabitant. |

Singing Over Babylon

|

Isaiah |

Jeremiah |

| 14:7 The whole earth is at rest, and is quiet: they break forth into singing.

8 Yea, the fir trees rejoice at thee, and the cedars of Lebanon, saying, Since thou art laid down, no feller is come up against us. |

51:48 Then the heaven and the earth, and all that is therein, shall sing for Babylon: for the spoilers shall come unto her from the north, saith the Lord. |

The Jewish Study Bible explains:

Jeremiah is steeped in prophetic traditions. He is familiar with the genre of visions (1:11–12, 13–19; cf. Amos 7:1–9), symbolic actions (Jeremiah 13:1–11), and oracles against the nations (ch 48 concerning Moab; cf. Isaiah chs 15 and 24; see Jeremiah 48:43 and Isaiah 24:17; to Edom in Jeremiah 49:7–22 and Obad.), and various other prophetic genres.

Further,

In some cases, there are significant similarities between oracles against the nations recited by different prophets (see esp. Jeremiah 49:9–16; Obad. 1:1–6), suggesting that prophets or editors of prophetic books borrowed from one another.30

The similarity between Isaiah’s and Jeremiah’s oracles against Babylon presents another problem of attribution, since Isaiah’s oracles in chapters 13, 14, and 21 are considered by most critical scholars to have a post-exilic period of composition. The Oxford Study Bible recognizes the problem and attempts to resolve it by suggesting multiple authorship for Jeremiah:

Persons other than [Jeremiah] and his biographer may be responsible for certain passages, especially within the [Page 19]‘prophecies against the nations’ (Ch. 46–51), but also elsewhere in the book. Some of the passages are written after the manner of Deuteronomy or in the style of the later chapters of Isaiah.31

The Jewish Study Bible similarly asserts that “Jeremiah’s ‘followers’ contribute similarities to Ezekiel and to Deutero-Isaiah.”32

The similarities in theme and phrasing continue with Isaiah’s and Jeremiah’s oracles against Moab:

Weeping Over Moab

|

Isaiah |

Jeremiah |

| 15:3 In their streets they shall gird themselves with sackcloth: on the tops of their houses, and in their streets, every one shall howl, weeping abundantly.

4 And Heshbon shall cry, and Elealeh: their voice shall be heard even unto Jahaz: therefore the armed soldiers of Moab shall cry out; his life shall be grievous unto him. 5 My heart shall cry out for Moab; his fugitives shall flee unto Zoar, an heifer of three years old: for by the mounting up of Luhith with weeping shall they go it up; for in the way of Horonaim they shall raise up a cry of destruction. 8 For the cry is gone round about the borders of Moab; the howling thereof unto Eglaim, and the howling thereof unto Beer-elim. 16:7 Therefore shall Moab howl for Moab, every one shall howl: for the foundations of Kir-hareseth shall ye mourn; surely they are stricken. |

48:3 A voice of crying shall be from Horonaim, spoiling and great destruction.

4 Moab is destroyed; her little ones have caused a cry to be heard. 5 For in the going up of Luhith continual weeping shall go up; for in the going down of Horonaim the enemies have heard a cry of destruction. 31 Therefore will I howl for Moab, and I will cry out for all Moab; mine heart shall mourn for the men of Kir-heres. 32 O vine of Sibmah, I will weep for thee with the weeping of Jazer: thy plants are gone over the sea, they reach even to the sea of Jazer: the spoiler is fallen upon thy summer fruits and upon thy vintage. |

Mourning Moab in the Body

|

Isaiah |

Jeremiah |

| 16:10 And gladness is taken away, and joy out of the plentiful field; and in the vineyards there shall be no singing, neither shall there be shouting: the treaders shall tread out no wine in their presses; I have made their vintage shouting to cease.

11 Wherefore my bowels shall sound like an harp for Moab, and mine inward parts for Kir-haresh. |

48:33 And joy and gladness is taken from the plentiful field, and from the land of Moab; and I have caused wine to fail from the winepresses: none shall tread with shouting; their shouting shall be no shouting.

36 Therefore mine heart shall sound for Moab like pipes, and mine heart shall sound like pipes for the men of Kir-heres: because the riches that he hath gotten are perished. |

[Page 20]

Pride of Moab

|

Isaiah |

Jeremiah |

| 16:66 ¶We have heard of the pride of Moab; he is very proud: even of his haughtiness, and his pride, and his wrath: but his lies shall not be so. | 48:29 We have heard the pride of Moab, (he is exceeding proud) his loftiness, and his arrogancy, and his pride, and the haughtiness of his heart.

30 I know his wrath, saith the Lord; but it shall not be so; his lies shall not so effect it. |

The Jewish Study Bible refers to Jeremiah’s oracles against Moab as “a funerary lament over Moab, comprised of phrases and themes from Isaiah 15:2–3, 7a, and 16:11.”33 This assessment seems to imply directionality in borrowing, that Jeremiah borrowed language from Isaiah in the production of the laments in Ch. 48. Schultz agrees:

Although it is easy to suggest why Jeremiah 48 uses some of the same descriptions of Moab as Isaiah 15–16, it is considerably more difficult to achieve any consensus regarding the nature and implications of these verbal parallels. If the possibility of an anonymous third source is excluded, nearly all scholars agree that it is Jeremiah 48 that is using Isaiah 15–16 (but not necessarily in its present canonical form) and not vice versa, noting that Isaiah 15–16 displays greater thematic unity, more appropriate contexts for the parallels, and superior textual readings, while Jeremiah 48 displays multiple borrowings and a more composite structure.34

The critical scholarly position seems to be that given the similarities between Isaiah’s and Jeremiah’s OAN passages, it is reasonable to assume that Jeremiah borrowed from Isaiah’s oracles, except in instances when those writings are assumed to be post-exilic in their composition (as evidenced by predictive prophecy or orientation toward a land that was not a “world power” during the time of Isaiah), in which case a later author or redactor was responsible for inserting the language into both prophetic books. Critical scholars prefer to imagine additional new authors for the book of Jeremiah (“followers” suggested previously in the Jewish Study Bible) than question the assumption that Isaiah would not have prophesied against Babylon.

The similarities between Isaiah’s and Jeremiah’s OANs present other interesting questions. In the Masoretic Hebrew text of the Bible as well as the Dead Sea Scrolls, Jeremiah’s OANs are placed toward the end of his writings after chapter 45, while in the Septuagint, they are found in the middle of Jeremiah’s writings, beginning in Chapter 25. Why the [Page 21]difference in placement? Is one sequence of writings more “authoritative” than the others? If it could be demonstrated with certainty that the Masoretic text best represents the earliest sequencing of the writings of Jeremiah, it might be easier to conclude that Jeremiah’s oracles against the nations were appended to his writings by a post-exilic author who was familiar with similar writings attributed to Isaiah. However, there is more scholarly consensus that the Septuagint provides the more reliable ordering of the text. The Anchor Bible Jeremiah commentary explains: “The location here [in the Septuagint] has long been thought to be earlier, which is doubtless correct. In the MT the Foreign Nation Oracles have been relocated to the end of the book, where they appear in Chaps. 46–51.”35

Finally, in another interesting example, Jeremiah seems to allude to language in Isaiah 53 as he describes the conspiracy of the men of Anathoth to silence him:

|

Jeremiah |

Isaiah |

| 11:19 But I was like a lamb or an ox that is brought to the slaughter; and I knew not that they had devised devices against me, saying, Let us destroy the tree with the fruit thereof, and let us cut him off from the land of the living, that his name may be no more remembered. (Emphasis added) | 53:7 He was oppressed, and he was afflicted, yet he opened not his mouth: he is brought as a lamb to the slaughter, and as a sheep before her shearers is dumb, so he openeth not his mouth.

8 He was taken from prison and from judgment: and who shall declare his generation? for he was cut off out of the land of the living: for the transgression of my people was he stricken. (Emphasis added) |

The similarities are enough to warrant consideration as yet another example of Jeremiah’s familiarity with Isaianic phrases that are typically assigned a post-exilic period of composition. However, this example differs from the affinities between the OANs in an important way: it demonstrates Jeremiah’s use of phrases from Isaiah 53 in a descriptive, poetic context, as if they come naturally to him due to his consideration or “pondering” of those passages over time. Lundbom’s Anchor Bible Jeremiah commentary seems to agree, as it refers the reader to Isaiah 53:7 and 8 in its discussion of Jeremiah 11:19, and suggests that Jeremiah identifies with the “suffering servant” of Isaiah 53.36 However, the commentary adds additional context to the passage, suggesting that the secretive actions of the conspirators against a proponent of Josiah’s reform, as well as Jeremiah’s young age at the time (assumed through [Page 22]textual hints), date the production of this passage to an early point in his career.

The aforementioned examples of similarities in texts, and the tracing of likely “borrowing” among prophetic works, are a fruitful area of exploration that should inform our evaluation of critical arguments for authorship and dating. They demonstrate the challenge of credulity that critical scholars face in assenting to Isaian influence on a significant amount of Jeremiah’s prophetic work, while reversing the directionality of borrowing, and even imagining additional authors for Jeremiah, when commonalities in the two texts seem to conflict with Duhm’s three-part division and the critical approaches to dating that have emerged over time to support it.

Productive Engagement with the Critical Position

As demonstrated in this paper, the assumptions Latter-day Saints bring to questions of scriptural authorship sharply diverge from those of most critical scholars. However, despite some compelling textual reasons to question the critical scholarly consensus around the dating of the material comprising the book of Isaiah, I believe it would be a tremendous mistake for Latter-day Saints to simply discard scholarly approaches to the book of Isaiah out of a desire to defend the historicity of the Book of Mormon.

The shift from an overly-simplistic imagining of Isaiah of Jerusalem penning every chapter of the book that bears his name, to a new imagining of a core set of Isaianic writings that were sealed up by Isaiah’s disciples (Isaiah 8:16) and then opened, assembled, expanded, and redacted over centuries, is a shift in thinking that makes possible new, helpful perspectives on the text for lay readers like me. For example, the critical scholarly assertion that Isaiah 14 is composed of two discrete poems37 is an extremely valuable insight that may help to explain other seemingly misplaced passages, such as prophecies of Christ nested in geopolitical discussions in chapters 7, 9 and 11. Though I consider much of the scholarly consensus around dating of the book to be unsupportable in light of Isaiah’s evident influence upon other, pre-exilic Biblical texts, I am entirely persuaded by the scholarly view of the compilation of the book by followers and disciples who were doing their imperfect best to assemble, make sense of, and assign context to, the elements of the book.

The idea that the three-part division model of authorship for the book of Isaiah must be entirely accepted or entirely discarded is a false [Page 23]binary choice that results in missed opportunities to develop a better, more nuanced understanding of the text.

Conclusion

The Latter-day Saint response to the theory of multiple authorship of Isaiah that prevails in critical scholarly circles should not be to engage critical scholars in their old arguments over multiple authorship vs. unity, or to provide yet another voice in smaller scholarly disputes over authorship at the level of chapter and verse. The differences in assumptions that Latter-day Saints bring to questions of production of scripture — including our experiences in observing and analyzing the production of the Book of Mormon and the Doctrine and Covenants — effectively constitute a barrier to entry for a Latter-day Saint response to the critical position on critical terms. This is not, however, a “surrender” to the critical position. On the contrary, it is an opportunity and invitation to develop a uniquely Latter-day Saint theory of authorship for Isaiah (and other books) using a toolset of very different assumptions:

- The statement in our Articles of Faith that “We believe the Bible to be the word of God as far as it is translated correctly” is an expression of how the Bible can serve as the word of God in influencing the life of the believer, and not an assertion that the Bible was authored or even compiled by God. The discussion of the transmission of the Biblical text in 1 Nephi 13:23–29 asserts a great deal of human error in the transmission of the Bible, resulting in the loss of “plain and precious things.” The Book of Mormon can serve not only as a corrective to extreme assumptions of textual infallibility, but also as a corrective to the excesses of modern critical scholarly perspectives on the formation and transmission of the Biblical text.

- Prophets can and do develop significant changes in perspective over time, even on very consequential matters.

- A prophet’s tone, phraseology, and topical emphasis are likely to change to significant degrees depending upon the prophet’s audience, specific life experiences, observations of social or geopolitical trends, or even the prophet’s own stage of life.

- Prophetic writings influence the work of later prophets, who respond to previous prophetic writings by incorporating, [Page 24]restating, alluding to, or sometimes even reversing the teachings of their predecessors.

- Prophets can predict future events before they come to pass.

- In questions of dating of scripture, the repeated presence of textual “borrowing” across authors carries far more evidential weight than anachronisms or other textual features that are possible results of redaction or simple misplacement of passages in the process of compiling a prophet’s writings.

With these assumptions in mind, it is possible to trace the enormous influence of Isaiah on other Old Testament and nonbiblical figures over time (as well as document the influence of previous books on Isaiah’s own thinking), and the picture that emerges is not of a marginal prophetic figure whose writings became a catch-all repository for a vast amount of pseudonymous material. On the contrary, what we see is a highly prophetic, influential, and evolving figure, whose writings were assembled, modified and edited over time, formed the basis for much of Lehite theology and self-perception, filled the caves at Qumran more than any other prophet, and served as the primary catalyst for Lehite and early Christian understanding of the mission of Jesus Christ.

Endnotes

- See Book of Mormon Introduction

- See Duhm, Bernhard, Das Buch Jesaia (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1892).

- When discussing multiple authors for Isaiah, scholars often use the terms proto, deutero, and trito to refer to the three supposed and unknown authors.

- For examples, see discussions in Terryl Givens, By The Hand of Mormon (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 136– 137, or Grant Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon: A Reader’s Guide (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), Kindle Locations 1671–1683.

- Sweeney, Marvin A., Isaiah 1–39: With an Introduction to Prophetic Literature, vol. 16, Forms of the Old Testament Literature (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2014), 41.

- Marvin A. Sweeney, Isaiah 40–66, ed. Rolf P. Knierim, Gene M. Tucker, and Marvin A. Sweeney, vol. 19, Forms of the Old Testament Literature (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2016), 33.

- Sweeney, Isaiah 40–66, 33.

- Ibid., 34.

- Ibid., 33.

- Ibid., 28–29.

- Joseph Blenkinsopp, Isaiah 40–55: a New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, 2nd ed., vol. 19a, Anchor Bible (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 53.

- David E. Bokovoy, Authoring the Old Testament: Genesis Deuteronomy, Kindle ed. (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2014), Kindle Location 496.

- Joseph Blenkinsopp, Isaiah 1–39: a New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, 2nd ed., vol. 19, Anchor Bible (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 2000), 277.

- James R. Mueller, Katharine Doob Sakenfeld, and M. Jack. Suggs, The Oxford Study Bible: Revised English Bible with the Apocrypha (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 717.

- Mueller, Sakenfeld, and Suggs, The Oxford Study Bible, 724.

- Roberts, J.J.M., and Peter Machinist, First Isaiah: a Commentary (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2016), 274.

- See Adams, La Mar, “ A Scientific Analysis of Isaiah Authorship,” BYU Religious Studies Center, accessed April 08, 2017, https://rsc.byu.edu/archived/isaiah-and-prophets-inspired-voices-old-testament/scientific-analysis-isaiah-authorship.

- Hugh Nibley, Since Cumorah (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1988), Kindle Location 3498–3505

- Blenkinsopp, Isaiah 1–39, 194, emphasis added.

- John Howard Raven, Old Testament Introduction, General and Special (New York: F. H Revell, 1906), 190–191.

- Blenkinsopp, Isaiah 40–55, 43.

- Grant Hardy, The Book of Mormon: A Reader’s Edition (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2006), 122–123.

- There is at least oblique reference to Nephi doing this. See 1 Nephi 19:23, where he mentions reading the scriptures to his people but notes that he “did liken all scriptures unto us” for the “profit and learning” of the people to whom he was preaching.

- Lundbom, Jack R. Jeremiah 21–36: a New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, 1st ed., Vol. 21b, Anchor Bible (New York: Doubleday, 2004), 165–166.

- Greenberg, Moshe, Ezekiel: a New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, 1st ed., vol 22a, Anchor Bible (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1983), 709.

- Blenkinsopp, Isaiah 1–39, 190.

- Schultz, Richard L., The Search for Quotation: Verbal Parallels in the Prophets, The Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2009), 306.

- Berlin, Adele, and Marc Zvi Brettler, The Jewish Study Bible, Kindle Edition, 2nd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), Kindle Locations 42374–42376.

- Mueller, Sakenfeld, and Suggs, The Oxford Study Bible, 716.

- Berlin and Brettler, The Jewish Study Bible, Kindle Locations 51476–51478.

- Mueller, Sakenfeld, and Suggs, The Oxford Study Bible, 778.

- Berlin and Brettler, The Jewish Study Bible, Kindle Locations 44918–44919.

- Ibid., 51560–51561.

- Schultz, The Search for Quotation, 317.

- Lundbom, Jeremiah 21–36, 59.

- Lundbom, Jack R., Jeremiah 1–20: a New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, 1st ed., Vol. 21a, Anchor Bible (New York: Doubleday, 1999), 637.

- Blenkinsopp, Isaiah 1–39, 285.

Go here to see the 31 thoughts on ““Their Imperfect Best: Isaianic Authorship from an LDS Perspective”” or to comment on it.