Part 1 ⎜ Part 2 ⎜ Part 3A ⎜ Part 3B ⎜ Part 3C ⎜ Part 3D ⎜ Part 3E ⎜ Part 4 ⎜ Part 5 ⎜ Part 6 ⎜ Part 7 ⎜ Part 8 ⎜ Postscript

Misrepresentations of Historical Sources

“This land,” “this country,” and “this continent” of America

The Annotated Edition of the Book of Mormon (AEBOM) quotes nineteenth century Latter-day Saint sources speaking of “this land,” “this country,” or “this continent” of America being the location of Book of Mormon events. The obvious aim of this endeavor is to create the impression that these statements can only be referring to the “heartland” of the United States, and not possibly Central or South America (22, 408, 417, 446, 462, 486, 498, 505, 518, 524–525, 549). However, this is a presentistic, anachronistic, and ideological reading of these sources. A survey of contemporary nineteenth century sources from both Latter-day Saints and non-Latter-day Saints reveals that “land,” “country,” and “continent,” both with and without the determiner this, were used broadly to cover a range of territory outside the continental United States. Such a survey also reveals that phrases such as “American continent” and the like (“America,” “American”) could subsume areas of Central and South America and even islands in the Caribbean. Take, for instance, these examples (italics used for emphasis):

- Francesco Saverio Clavigero (1807): “Of the ancient quadrupeds, by which we mean those that have from time immemorial been in that country, some were common to both the continents of Europe and America, some peculiar to the new world, in common however to Mexico and other countries of North or South America, others were natives only to the kingdom of Mexico. . . . The quadrupeds which are common to Mexico . . . [include] the Cojametl, to which, from its resemblance to the wild boar, the Spaniards gave the name of Javali, or wild hog, is called in other countries of America Pecar, Saino, and Tayassu.”[1]

- Noah Webster (1828): “AMER’ICA, noun [from Amerigo Vespucci, a Florentine, who pretended to have first discovered the western continent.] One of the great continents, first discovered by Sebastian Cabot, June 11, O.S. 1498, and by Columbus, or Christoval Colon, Aug. 1, the same year. It extends from the eightieth degree of North, to the fifty-fourth degree of South Latitude; and from the thirty-fifth to the one hundred and fifty-sixth degree of Longitude West from Greenwich, being about nine thousand miles in length. Its breadth at Darien is narrowed to about forty-five miles, but at the northern extremity is nearly four thousand miles. From Darien to the North, the continent is called North America and to the South, it is called South America.”[2]

- W. W. Phelps (1833): “We are glad to see the proof [ruins from ‘Peten, in Central America’] begin to come, of the original or ancient inhabitants of this continent. It is good testimony in favor of the book of Mormon, and the book of Mormon is good testimony that such things as cities and civilization, “prior to the fourteenth century,” existed in America. Helaman, in the book of Mormon, gives the following very interesting account of the people who lived upon this continent, before the birth of the Savior.”[3]

- Eli Gilbert (1834): “If Moses and the prophets, Christ and his apostles, were the real authors of the bible, chiefly revealed and written on the continent of Asia, was not the book of Mormon also written by men who were divinely inspired by the Holy Spirit, on the continent of America? And did not Jesus Christ as truly appear on the continent of America, after his resurrection, and choose twelve apostles to preach his gospel; and did he not deliver his holy doctrine, and teach the same to numerous multitudes on this American continent?”[4]

- William Smith (1837): “Now, the beauty of this simile or figure can only be discovered by those who take the pains to contrast it with the literal fact as it occurred; the relation of which may be found in the Book of Mormon, first Book of Nephi, where a remnant of the branches or seed of Joseph are represented as crossing the sea, and settling this continent of North and South America.”[5]

- Parley P. Pratt (1838): “And not only does this page set the time for the overthrow of our government and all other Gentile governments on the American continent, but the way and means of this utter destruction are clearly foretold, namely, the remnant of Jacob will go through among the Gentiles and tear them in pieces, like a from among the flocks of sheep.”[6]

- Joseph Smith (1841): “[Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatán] unfolds & developes many things that are of great importance to this generation & corresponds with & supports the testimony of the Book of Mormon; I have read the volumnes with the greatest interest & pleasure & must say that of all histories that have been written pertaining to the antiquities of this country it is the most correct luminous & comprihensive.”[7]

- Joseph Smith (1842): “[Reviewing the contents of Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatán] If men, in their researches into the history of this country, in noticing the mounds, fortifications, statues, architecture, implements of war, of husbandry, and ornaments of silver, brass, &c.—were to examine the Book of Mormon, their conjectures would be removed, and their opinions altered; uncertainty and doubt would be changed into certainty and facts; and they would find that those things that they are anxiously prying into were matters of history, unfolded in that book. They would find their conjectures were more than realized—that a great and a mighty people had inhabited this continent—that the arts sciences and religion, had prevailed to a very great extent, and that there was as great and mighty cities on this continent as on the continent of Asia. Babylon, Ninevah, nor any of the ruins of the Levant could boast of more perfect sculpture, better architectural designs, and more imperishable ruins, than what are found on this continent. Stephens and Catherwood’s researches in Central America abundantly testify of this thing. The stupendous ruins, the elegant sculpture, and the magnificence of the ruins of Guatamala, and other cities, corroborate this statement, and show that a great and mighty people—men of great minds, clear intellect, bright genius, and comprehensive designs inhabited this continent. Their ruins speak of their greatness; the Book of Mormon unfolds their history.”[8]

- George Adams (1842): “He introduced an account of many American antiquities together with the discoveries lately made by Mr. Stevens [John Lloyd Stephens, author of Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatán] that all go to prove that the American Indians were once an enlightened people and understood the arts and sciences, as the ruined cities and monuments lately discovered fully prove. He then declared that this record had not come forth in the place of the Bible, but in fulfilment of the Bible; that its coming forth clearly demonstrated that Jesus had been as good as his word, viz: he told his disciples he had other sheep that were not of that fold (in Jerusalem) and they also should hear his voice, for he was sent to the lost sheep of the house of Israel,—and some of the lost sheep of the house of Israel, viz:—of the tribe of Joseph being in America, it was necessary Jesus should visit them, as also the ten tribes in the “north country.” He declared that Jesus did visit both the above named branches of the house of Israel during the forty days before his final ascension from the Mount of Olives, and that the Book of Mormon was not only a history of the dealings of God with the descendants of Joseph on this continent previous to the crucifixion of our Lord, but also an account of the gospel as established among them by the personal appearance of Christ on this continent, and that the account of the gospel in the Book of Mormon agreed with the account in the Bible.”[9]

- John E. Page (1842): “The city [Moronihah] was in some region on the South of what is called at this time, North America, and at the time our Lord Jesus Christ was crucified, near Jerusalem, in Asia. At that time there was a terrible destruction on this continent, because of the wickedness of the people, at which time those cities were destroyed . . . . And how was you destroyed? was the inquiry of those efficient antiquarians Messrs. Catherwood and Stephens, the charge d’affairs of these United States, as they sit on the wondrous walls of “Copan” . . . . Read book of Mormon, 3d edition, page 549. Let the reader observe, that the book of Mormon was published A. D. 1830. The discovery of this city by Messrs. Catherwood and Stephens was in 1840. Read Stephens’ travels in Central America, vol. i. page 130, 131, &c. Mr. Stephens states, ‘There is no account of these ruins until the visit of Col. Galindo in 1836, before referred to, who examined them under a commission from the Central American government.’ Question.—If the book of Mormon is a fiction, no difference who wrote it, how did it happen to locate this city so nicely before it was known to exist till 1836 by any account that was extant in America, from which it could have been extracted?”[10]

- William H. Prescott (1843): “On the opposite borders of the largest of these basins, much shrunk in its dimensions since the days of the Aztecs, stood the cities of Mexico and Tezeuco, the capitals of the two most potent and flourishing states of Anahuac, whose history, with that of the mysterious races that preceded them in the country, exhibits some of the nearest approaches to civilisation to be met with anciently on the North American continent.”[11]

- William H. Prescott (1843): “A hidalgo of Cuba, named Hernandez de Cordova, sailed with three vessels on an expedition to one of the neighbouring Bahama Islands, in quest of Indian slaves. (February 8, 1517.) He encountered a succession of heavy gales which drove him far out of his course, and at the end of the three weeks he found himself on a strange but unknown coast. On landing and asking the name of the country, he was answered by the natives, ‘Tectetan,’ meaning ‘I do not understand you,”–but which the Spaniards, misinterpreting into the name of the place, easily corrupted into Yucatan. Some writers give a different etymology. Such mistakes, however, were not uncommon with the early discoverers, and have been the origin of many a name on the American continent.”[12]

- William H. Prescott (1843): “Two of the highest mountains on the North American continent [are] Popocateptl . . . and Iztaccihuatl [two volcanos in Mexico].”[13]

- William H. Prescott (1843): “It was the glory of the Aztec, as of the other races on the North American continent, to show how the spirit of the brave man may triumph over torture and the agonies of death.”[14]

- William H. Prescott (1843): “But, if the remains on the Mexican soil are so scanty, they multiply as we descend the south-eastern slope of the Cordilleras, traverse the rich valley of Oaxaca, and penetrate the forests of Chiapa and Yucatan. In the midst of these lonely regions, we meet with the ruins, recently discovered, of several ancient cities, Mitla, Palenque, and Itzalana or Uxmal, which argue of a higher civilisation than anything yet found on the American continent.”[15]

- George Adams (1844): “There is no place except North and South America to which they could have gone, if the old world furnishes no trace of them. The Continent of America is the only place where the prophecies concerning Joseph and his seed could be fulfilled.”[16]

- John E. Page (1844): “I have in possession the histories of the anticquities < of America > By [John Lloyd] Stephens, [Josiah] Priest, and [John] Delafield— all of which Books are of later-date than the Book of Mormon and they being disinterested witnesses to the Book of Mormon the public mind is perfectly astounded to heare the vast, amount of correspondence in print of character and location of the anticquities of America as set forth first in the Book of Mormon in 1830 and then sustained by < ✓Messrs— > Priest in 1833 and Delafield in 1839 and Catherwood and Stephens in 1841— & 42 showing positively and demonstratively in the moust most profound sense of the terms that it was out of the reach of speculative impostures to have orriginated the matter contained in the Book of Mormon in point of charecter and location of the antiquities of America unless the author was aided either by Books.”[17]

- A. Van Heuvel (1844): “Such [gold ornaments] were found at an early period after the discovery of this Continent, among some American Indians, as on the coast of Yucatan.”[18]

- James K. Polk (1844): “We may claim on this continent a like exemption from European powers. . . . The people of the United States cannot, therefore, view with indifference attempts of European Powers to interfere with the independent action of the nations on this continent.”[19]

- John McIntosh (1844): “Such is the information which eminent geographers and the most authentic Spanish writers give us, respecting the early history of the Mexicans. That they were found to be a superior race to the various tribes which inhabited this continent, when America was first visited by Europeans, cannot be denied, if a partial knowledge of the arts be a constituent part of refinement and civilization. It is the opinion of all those who have made inquiries after the origin and descent of the Mexicans, or about those vestiges of civilization which are found throughout the continent of America, that they are the descendants of an Asiatic colony from Corea, which was at the time of the migration into America, a tributary to the Chinese empire.”[20]

- John McIntosh (1844): “They might as we have already mentioned, when we alluded to the antiquities of North America, disappear, from the prevalent custom, among the different tribes who inhabited this continent, of burying those weapons and other useful tools with the dead. It might also be asked, why the Mexicans, since their arrival on this continent, did not practice the art of making swords and different other instruments which have been found in the tumuli of the dead, both in the northern and southern parts of America.”[21]

- John McIntosh (1844): “Though it be possible that America may have received its first inhabitants from our continent, either by the north-west of Europe, or the north-east of Asia, there seems to be good reason for supposing that the progenitors of all the American nations from Cape Horn to the southern confines of Labrador, migrated from the latter rather than the former. The Esquimeaux [Eskimos] are the only people in America, who in their aspect or character, bear any resemblance to the northern Europeans. They are manifestly a race of men distinct from all the nations of the American continent, in language, in disposition, and habits of life.”[22]

- John C. Calhoun (1844): “But, to descend to particulars: it is certain that while England, like France, desires the independence of Texas, with the view to commercial connections, it is not less so, that one of the leading motives of England for desiring it, is the hope that, through her diplomacy and influence, negro slavery may be abolished there, and ultimately, by consequence, in the United States, and throughout the whole of this continent. . . . What would be the consequence if this object of her unceasing solicitude and exertions should be effected by the abolition of negro slavery throughout this continent, some idea may be formed from the immense diminution of productions, as has been shown, which has followed abolition in her West India possessions. But, as great as that has been, it is nothing compared to what would be the effect if she should success in abolishing slavery in the United States, Cuba, Brazil, and throughout this continent. . . . Very different would be the result of abolition, should it be effected by her influence and exertions in the possession of other countries on this continent–––and especially in the United States, Cuba, and Brazil, and the great cultivators of the principal tropical productions of America. …They are of vast extent, and those beyond the Cape of Good Hope possessed of an unlimited amount of labor, standing ready, by the aid of British capital, to supply the deficit which would be occasioned by destroying the tropical productions of the United States, Cuba, Brazil, and other countries cultivated by slave labor on this continent. . . . Is it not better for them that they should be supplied with tropical products in exchange for their labor from the United States, Brazil, Cuba, and this continent generally, than to be dependent on one great monopolizing power for their supply? . . . Viewed in connection with them, the question of annexation becomes one of the first magnitude, not only to Texas and the United States, but to this continent and Europe.”[23]

- Francis Lieber (1844): “From the general division of America into lofty mountainous plateaus and very low plains, there results a contrast between two climates, which, although of an extremely different nature, are in almost immediate proximity. Peru, the valley of Quito, and the city of Mexico, though situated between the tropics, owe to their elevation the general temperature of spring. They behold the paramos, or mountain ridges, covered with snow, which continues upon some of the summits almost the whole year, while, at the distance of a few leagues, an intense and often sickly degree of heat suffocates the inhabitants of the ports of Vera Cruz and Guayaquil. These two climates produce each a different system of vegetation. The flora of the torrid zone forms a border to the fields and groves of Europe. Such a remarkable proximity cannot fail for frequently occasioning sudden changes, by the displacement of these two masses of air, so different constituted–––a general inconvenience, experience over the whole of America. Every where, however, this continent is subject to a lower degree of heat than the same latitudes in the eastern portion of the earth. . . . The comparative narrowness of this continent; its elongation towards the icy poles; the ocean, whose unbroken surface is swept by the trade winds; the currents of extremely cold water which flow from the straits of Magellan to Peru; the numerous chains of mountains, abounding in the sources of rivers, and whose summits, covered with snow, rise far above the region of the clouds; the great number of immense rivers, that, after innumerable curves, always tend to the most distant shores; deserts, but not of sand, and consequently less susceptible of being impregnated with heat; impenetrable forests, that spread over the plains of the equator, abounding in rivers, and which, in those parts of the country that are farthest distant from mountains and from the ocean, give risen to enormous masses of water, which are either attracted by them, or are formed during the act of vegetation,–––all these causes produce in the lower parts of America, a climate which, from its coolness and humidity, is singularly contrasted with that of Africa. . . . Throughout the southern portion of this continent, and in the West India islands, this species (blatta Americana), called Kakkerlac by the Dutch, is very numerous and troublesome. The blatta Orientalis, or common kitchen cockroach, was originally brought from Asia to Europe, and thence to America. It is now thoroughly domiciliated in all parts of our country, to the great vexation of its inhabitants.”[24]

- Orson Hyde (1853): “Spain must give up Cuba; England, Canada; and the United States of America must hold, as her dependencies, every country on the Western Continent, with the islands along its borders. Mexico would not allow our agents to preach the Gospel within her borders. The Catholic faith, sustained by political power, to the exclusion of all others, is a cause sufficient for revolutions at home, and for a conquest by a power whose policy it is to let religion stand upon its own merits.”[25]

- Orson Pratt (1854): “Were it not for this choice and invaluable work, the history of the ancient nations who once peopled this vast continent, would have slumbered in perpetual darkness: all efforts to have penetrated the mists of antiquity would have been in vain. The magnificent ruins of [Central American] ancient cities, palaces, and temples, buried in primeval forests, would alone have proclaimed in silent grandeur, the strength and greatness of the former population. The Book of Mormon, then, as an ancient history, and the only history which we have of ancient America, is of priceless value — a gem most precious.”[26]

- Orson Pratt (1854): “From the revelations which God has given, there is no doubt but there has been a most wonderful change. By them we learn that the Eastern and Western Continents were one; whilst the waters occupied the polar regions of our globe. America, Europe, Asia, Africa, and many Islands of the sea, were all one land.”[27]

- Jedediah M. Grant (1854): “We see it in the revolutions of our own continent; we see it in the scattering and scourging of the house of Israel; in the fading away of nations, on the right and on the left; in the present commotion in our own nation; in the broils and contentions between the South and the North; in short, we see it in all the events connected with our own and other nations living on the continent of North and South America.”[28]

- Frank P. Blair (1859): “All the Spanish States of this continent have, in their new organization, made our Government their exemplar.”[29]

- Brigham Young (1863): “If this had continued in our nation, it would not merely have annexed Texas to our flag, but would have added the whole continent of North and South America.”[30]

- Orson Pratt (1872): “About fifty‐four years before Christ, five thousand four hundred men, with their wives and children, left the northern portion of South America, passed through the Isthmus, came into this north country, the north wing of the continent, and began to settle up North America, and from that time a great emigration of the Nephites and the people of Zarahemla took place year by year. . . . What is it that has disrupted and apparently thrown the western continent into such terrible convulsion as to place the rocks on edge and rend them asunder? . . . From the frozen regions of the north until you penetrate through the Isthmus into the Andes, and then on to the end of this continent in the south, we find these disruptions, seams and cracks among the various strata of rock. Before the coming of Christ this was not so.”[31]

- Orson Pratt (1873): “The Prophet said that these plates of brass should not be dimmed by time, that God would preserve them to the latest generations. What for? In order that they might come forth and their contents be translated by the Urim and Thummim, that these contents might be declared to all nations, and kindreds, and tongues, and people, who were the descendants of Lehi upon the face of all this continent, from the frozen regions of the north to the very utmost extremities of South America. That all these nations should come to a knowledge of the things contained on those plates of brass.”[32]

- Brigham Young (1876): “Nor do I expect we shall stop at Arizona, but I look forward to the time when settlements of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints will extend right through to the city of Old Mexico, and from thence on through Central America to the land where the Nephites flourished in the Golden era of their history, and the great backbone of the American continent be filled, north and south, with the cities and temples of the people of God. In this great work I anticipate the children of Nephi, of Laman and lemuel [native Indians] will take no small part.”[33]

- George Reynolds (1891): “After many days, the vessel with its precious freight reached the shores of this continent, at a place, we are told by the Prophet Joseph Smith, near where the city of Valparaiso, Chili, now stands.”[34]

- George Reynolds (1891): “The course taken by Lehi and his people has been revealed with some detail. We are told by the Prophet Joseph Smith that Lehi and his company traveled in nearly a south-southeast direction until they came to the nineteenth degree of north latitude, then, nearly east to the sea of Arabia, then sailed in a southeast direction, and landed on the continent of South America, in Chili, thirty degrees south latitude. This voyage would take them across the Indian and South Pacific Oceans. . . . Shortly after the arrival of Lehi and his little party on this continent, Nephi received a commandment from the Lord to make certain plates of ore on which to engrave the doings of his people.”[35]

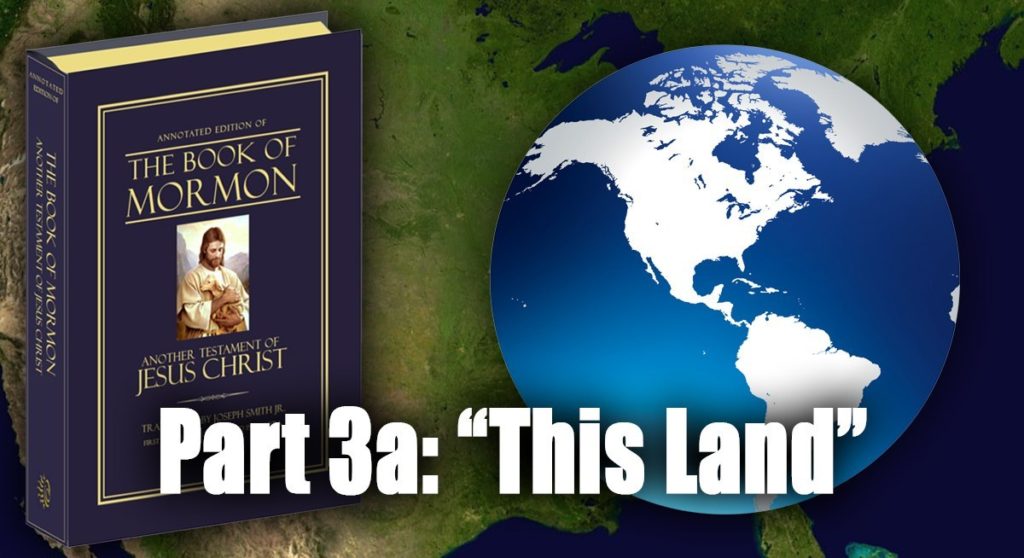

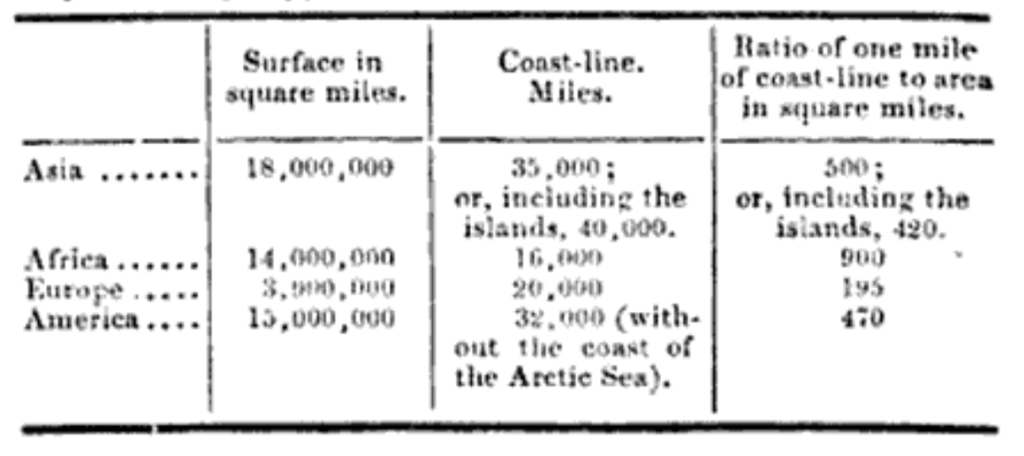

This expansive definition of the American “continent” to include both North and South America is reflected in additional sources, such as Charles Knight’s 1841 encyclopedia which defines the span of the American continent in comparison with Asia, Africa, and Europe as being 15,000,000 square miles, with 32,000 miles of ocean coastline “without the coast of the Arctic Sea.”[36] This can only make sense if one includes all of North and South America, as the continental United States today is only roughly 3 million square miles of contiguous land.[37]

A chart from Knight’s Store of Knowledge (1841) giving the surface area of America in square miles.

There is no good reason to exclude Central or South America from the use of “this land” or “this continent” of “America” by nineteenth century Latter-day Saint sources, including Joseph Smith. On the contrary, Latter-day Saints well into the beginning of the twentieth century shared “a common understanding” of a hemispheric geography for Book of Mormon events “by placing the Nephites in South America and the Jaredites in North America.”[38] Accordingly, “this land” and “this continent” of “America” could only have had hemispheric connotations in these sources.[39] This is consistent with contemporary nineteenth century non-Latter-day Saint usage of the same phraseology, thus demonstrating that such was commonplace in the immediate English-language culture of the Book of Mormon’s first readers.

Even into the twentieth century, highly influential Latter-day Saint writers such as Elder B. H. Roberts continued to have a hemispheric geography in mind while employing this verbiage.[40] “The Book of Mormon reveals the fact that there existed two great civilizations on the American continent,” wrote Roberts in 1907. “The first [the Jaredites] was established by a colony which left the valley of the Euphrates in very ancient times, established themselves in the North American continent, and in time grew to be a great nation far advanced in civilization . . . The second civilization [the Nephites and Lamanites] resulted from two colonies which came from Judea; one led by Lehi, landing in South America; the other colony was led by Mulek, who escaped from Palestine after the overthrow of Jerusalem by the Babylonians. This colony landed in North America.”[41] With his hemispheric geography in mind, Roberts continued to write how “the Book of Mormon gives a voice to the ruined cities and half buried monuments upon this land of America.”[42]

Contrary to the efforts of Hocking and Meldrum to create a false impression that this phraseology could only have meant the United States, the use of “this land” and “this continent” to describe the events of the Book of Mormon in early Latter-day Saint geographical discourse does “not exclude any portion of the Americas but [is] consistent with the hemispheric view of the Book of Mormon espoused by early Latter-day Saints.”[43] To insist otherwise is to force these sources into an ideological position that is alien to the worldview of early Latter-day Saints. As Andrew H. Hedges has succinctly summarized,

To think . . . that the phrase “this continent” in these documents necessarily meant “North America” to early nineteenth century Americans, or that “America” or “this country” meant the “United States,” would be a mistake. . . . For Joseph and his contemporaries, “continent” typically meant “a great extent of land, not disjoined or interrupted by a sea; a connected tract of land of great extent; as the Eastern and Western continent.” In at least one of the letters cited above, in fact, “this continent” is indeed juxtaposed with “the eastern continent,” reflecting this hemispheric approach to the word rather than the more narrow definition most people would give it today. Similarly, “America,” was considered “one of the great continents, . . . extend[ing] from the eightieth degree of North, to the fifty-fourth degree of South Latitude”—that is, all of North and South America combined. True, “[f]rom Darien to the North, the continent [was] called North America, and to the South, it [was] called South America,” but the singular noun makes it clear that “America” alone included everything from Point Barrow to the Cape of Good Hope. “Country,” too, carried the same ambiguity, which explains how either Joseph or John Taylor, writing from Nauvoo in 1841, could praise John Lloyd Stephens’ book on Central American ruins as “the most correct luminous & comprihensive . . . of all the histories that have been written pertaining to the antiquities of this country.” “Indian,” defined as “any native of the American continent,” incorporated the imprecision already inherent in “continent” and “America.” Even the phrase “our western tribes of Indians” does little to clear things up, given how broadly “west” and “western” were, and continue to be, used.[44]

Endnotes

[1] Francesco Saverio Clavigero, The History of Mexico, 3 vols. (London: J. Johnson, 1807), 1:37–38, emphasis added. Clavigero, The History of Mexico, 1:46, 475, likewise speaks of “other parts of North America subject to the Spanish” and the “pyramids of Teotihuacan” as part of “the pyramids of America” which “no Indian historian” has been able to explain.

[3] “Discovery of Ancient Ruins in Central America,” Evening and Morning Star 1 no. 9 (February, 1833): 71.

[4] “Communication from Eli Gilbert,” Latter Day Saints’ Messenger and Advocate 1, no. 1 (October 1834): 10.

[5] William Smith, “Evidences of the Book of Mormon,” Latter Day Saints’ Messenger and Advocate 3 no. 4 (January, 1837), 434.

[6] Parley P. Pratt, Mormonism Unveiled (New York, 1838), 15.

[8] Times and Seasons, 15 July 1842. Whether or not Joseph Smith was the actual author of this editorial (there is evidence for at least some of his involvement in its composition), he was the nominal editor of the paper at the time of its publication, and thus it can be classified as a Joseph Smith document per the standards of the Joseph Smith Papers Project, which classifies such as “documents created by Joseph Smith or by staff whose work he directed, including journals, revelations and translations, contemporary reports of discourses, minutes, business and legal records, editorials, and notices.” See

“About the Project” online at the Joseph Smith Papers; Matthew Roper, Paul J. Fields, and Atul Nepal, “Joseph Smith, the Times and Seasons, and Central American Ruins,” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 22, no. 2 (2013): 84–97.

[10] John E. Page, “To a Disciple,” Morning Chronicle (1 July 1842).

[11] William H. Prescott, History of the Conquest of Mexico, 3 vols. (London: George Routledge and Sons, 1843), 3:4.

[12] Prescott, History of the Conquest of Mexico, 3:71–72.

[13] Prescott, History of the Conquest of Mexico, 3:181.

[14] Prescott, History of the Conquest of Mexico, 3:224.

[15] Prescott, History of the Conquest of Mexico, 3:469.

[16] George Adams, A Lecture on the Authenticity & Scriptural Character of the Book of Mormon (Boston: J. E. Farwell, 1844), 17.

[18] J. A. Van Heuvel, El Dorado (New York: J. Winchester, 1844), 68.

[19] James K. Polk, Message from the President of the United States to the Two Houses of Congress at the Commencment of the Second Session of the Twenty-Eight Congress, December 3, 1844 (Washington, D.C.: Gales and Seaton, 1844), 14.

[20] John McIntosh, The Origin of the North American Indians (New York: Nafis and Cornish, 1844), 291.

[21] McIntosh, The Origin of the North American Indians, 298.

[22] McIntosh, The Origin of the North American Indians, 310.

[23] John C. Calhoun to Wilson Shannon, June 20, 1844, “Correspondence with Mexico and Texas on the Subject of Annexation,” Appendix to the Congressional Globe (December 1844), 6–7.

[24] Francis Lieber, ed., Encyclopædia Americana: A Popular Dictionary (Philadephia: Lea and Blanchard, 1844), 3:252, 286.

[25] Orson Hyde, “Celebration of American Independence,” July 4, 1853, Journal of Discourses 7:109.

[26] Orson Pratt, “Questions and Answers on Doctrine,” The Seer 2, no. 2 (February 1854): 212–213.

[27] Orson Pratt, “Formation of the Earth,” The Seer 2, no. 4 (April 1854): 250.

[28] Jedediah M. Grant, “Fulfillment of Prophecy,” April 2, 1854, Journal of Discourses 2:146.

[29] Frank P. Blair, An Address Delivered Before the Mercantile Library Association of Boston, Massachusetts (Washington, D.C.: Buell & Blanchard, 1859), 23.

[30] Brigham Young, “Knowledge, Correctly Applied, The True Source of Wealth and Power,” May 31, 1863, Journal of Discourses 10:189.

[31] Orson Pratt, “Nephite America,” February 11, 1872, Journal of Discourses 14:326, 328.

[32] Orson Pratt, “Meeting of Adam With His Posterity in the Valley of Adam‐Ondi‐Ahman,” May 18, 1873, Journal of Discourses 16:55.

[33] Brigham Young to William C. Staines, 11 January 1876, Letterbook 14:124-26, cited in Leonard J. Arrington, Brigham Young: American Moses, rep. ed. (New York, N.Y.: Vintage, 2012), 382.

[34] George Reynolds, A Dictionary of the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City, UT: Joseph Hyrum Parry, 1891), 216.

[35] Reynolds, A Dictionary of the Book of Mormon, 217, 276.

[36] Charles Knight, ed., Knight’s Store of Knowledge (London: Charles Knight & Co., 1841), 381.

[38] Karen Lynn Davidson et al., eds., The Joseph Smith Papers, Histories, Volume 1: Joseph Smith Histories, 1832–1844 (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church Historians Press, 2012), 519.

[39] See further Matthew Roper, “Limited Geography and the Book of Mormon: Historical Antecedents and Early Interpretations,” FARMS Review 16, no. 2 (2004): 229–255.

[40] B. H. Roberts espoused a hemispheric view of Book of Mormon geography in his monumental A New Witness for God, 3 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1909–1911).

[41] B. H. Roberts, Defense of the Faith and the Saints, 2 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1907), 1:362–363.

[42] Roberts, Defense of the Faith and the Saints, 1:364.

[43] Roper, “Joseph Smith, Revelation, and Book of Mormon Geography,” 49, emphasis in original.

This article is cross-posted with the permission of the author, Stephen O. Smoot, from his blog at https://www.plonialmonimormon.com.