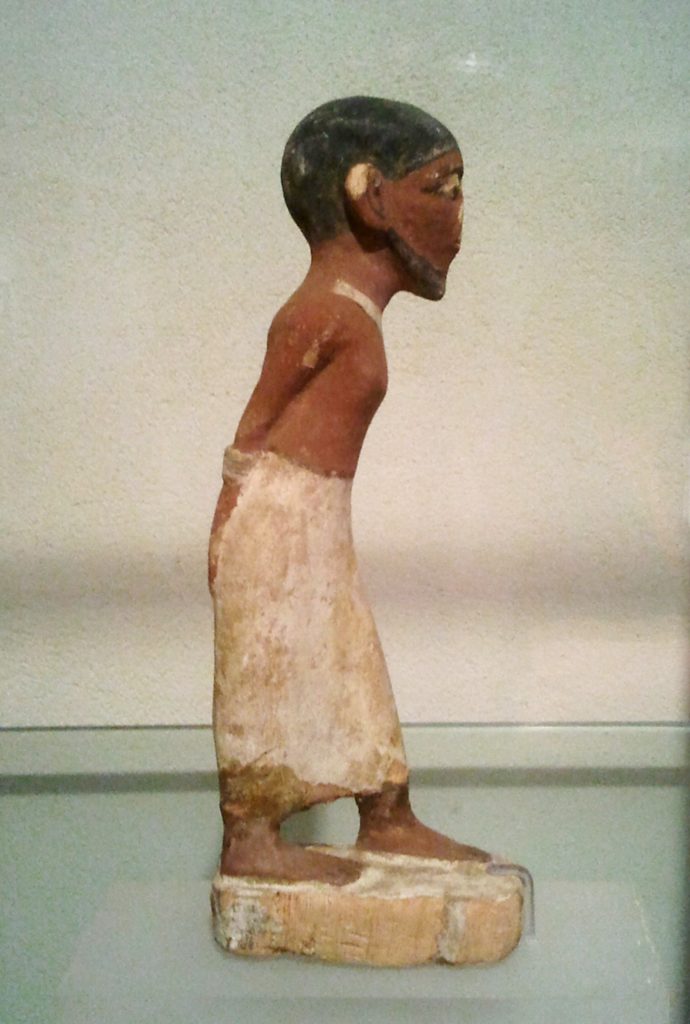

Figure 1. Egyptian Figurine of a Semitic Slave[2]

Figure 1. Egyptian Figurine of a Semitic Slave[2]

Question: Many people nowadays believe that the Exodus never happened. Are there traces of the historical Exodus from sources outside the scriptures? And do they help us to identify the Pharaoh of the Exodus?

Summary: Traces of the historical Exodus from sources outside the scriptures are available — but only if you are looking for the right things in the right direction. For example, if you are expecting to find archaeological evidence for a group of millions of Israelites crossing the Sinai desert after leaving Egypt in shambles, you are likely to be disappointed. True it is that large numbers of Semitic people came and went from Egypt in the centuries before a much smaller group eventually left in the Exodus. But teasing out the subtleties of the historical context of scripture requires tedious and diligent efforts of dedicated scholars. In this article, we present a few tentative conclusions to help familiarize readers with the current landscape.

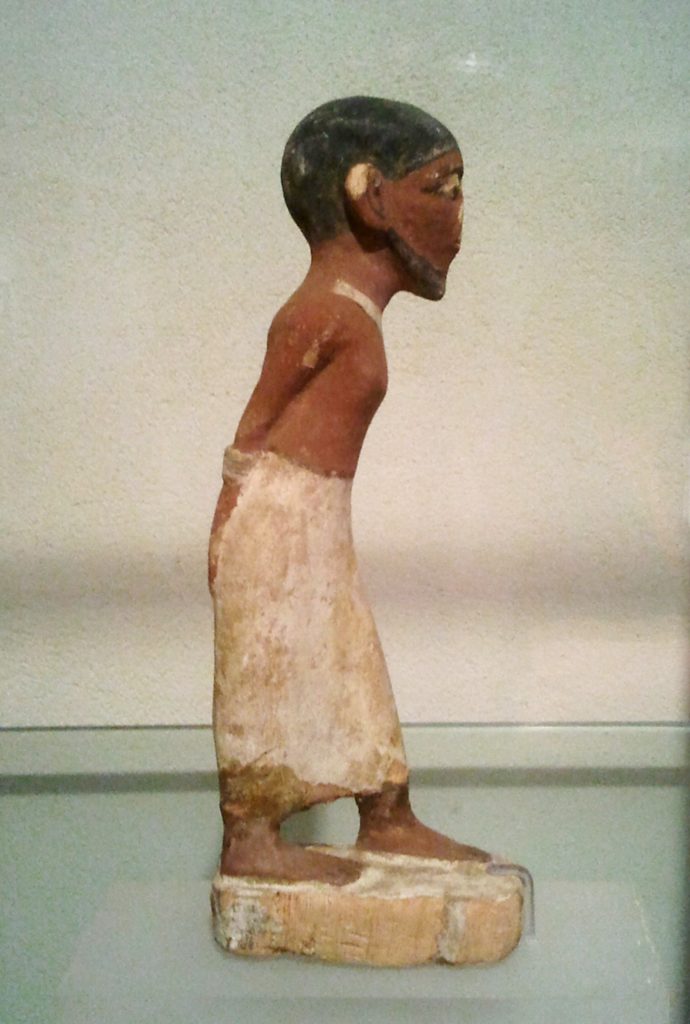

Figure 2. Wallpainting of Brickmaking in the Tomb of Rekhmere,

vizier under Pharoahs Thutmosis III and Amenophis II.[3]

How Should We Regard Current Scholarship about the Exodus?

How should we reconcile study and faith in our search for scriptural understanding? Though the scriptures are not without historical value, they were not meant to be read simply as history textbooks. Unlike modern historians, the authors of scripture “never wrote with the disinterested aim of chronicling the past for its own sake; rather, deeds of the past were harnessed … to persuade readers to take action in the present”[4] — to spur individuals to exercise faith in God and to emulate the virtues of their forebears. As the Roman rhetorician, Quintilian, summed up the prime role of history as exhortation rather than argumentation in his day: “History is written for telling, not proving.”[5] However, in our day, because the “immediate certainty”[6] of the truth of the Bible and the reality of God is no longer automatically assumed, the focus of most biblical scholarship has become just the opposite: proving, not telling.[7] Many people today seek to verify the “facts” of Bible history through non-biblical sources as a confirmation that the scriptural records in which they are asked to place their trust reflect “reality,” not merely memories of ancient fables.[8]

Sound scholarship in any domain of learning should be welcomed with gratitude rather than fear. This was the attitude of Elder James E. Talmage, who wrote: “Within the Gospel of Jesus Christ there is room and place for every truth thus far learned by man or yet to be made known.”[9] If the pursuit of secular perspectives on scripture history and teachings is undertaken in a thoughtful and balanced way, it will enrich our faith. Indeed, LDS scripture explicitly teaches that study and faith are allies in spiritual understanding.[10] While affirming that “faith and testimony … are ultimately matters of the Spirit,” Elder Jeffrey R. Holland taught that “that truly rock-ribbed faith and uncompromised conviction comes with its most complete power when it engages our head as well as our heart.”[11]

In all study, however, faith must retain its essential primacy.[12] As Holmes Rolston observed, “The religion that is married to [scholarship] today will be a widow tomorrow. … Religion that has too thoroughly accommodated to any [scholarship] will soon be obsolete.”[13] J. D. Pleins reminds us that:[14]

we should acknowledge that not all questions can be answered definitively. This is the nature of the human quest, whether in the realm of science or religion. The answers we have are merely provisional. The search for any final truths is an all-consuming, lifelong task. Faith should not shun the historian’s discoveries, but neither will faith expect the historian to solve all questions. Faith can certainly benefit from seeing in the archaeologist’s persistent probing a kindred spirit in the search for elusive truths. Historical truth is a moving target, not a rock upon which to build faith. Faith, likewise, has its own work to do and cannot wait for the arrival of the latest issue of Near Eastern Archaeology before trying to sort things out.

We should avoid the example of the man who found himself in a burning building and said: “I’m not leaving this spot until someone tells me exactly how all this got started.”

In this article, we will provide a brief sampling of the kinds of things that are being studied today about the historical Exodus from outside the scriptures, not forgetting that many of the tentative conclusions presented here are controversial today and may well be overturned tomorrow. On the positive side, the last several years have seen many lines of dedicated research from diverse disciplines — once thought of as irreconcilable — begin to converge. Just as a study of documents and sites relating to Church history contributes to our understanding of the revelations and teachings of the Doctrine and Covenants, so the study of non-Israelite texts and archaeological findings can illuminate our study of ancient scripture.

First, we will outline why the historical context of the Exodus is a difficult and controversial issue for scholars. Then, we will outline how some of the historic events of the Exodus might have unfolded in light of current scholarship. Finally, we will present some tentative conclusions about the dating of the Exodus, including a proposal for the pharaohs of the Exodus.

Why Is the Historical Exodus Difficult and Controversial Among Scholars?

Recent decades have witnessed an increase in scholars who question whether there is any historical basis to the biblical account. For instance, after critiquing the efforts of a colleague who had argued for an unlikely timeline for the events of Exodus, archaeologist James K. Hoffmeier tellingly concluded his review by exhorting his evangelical colleagues “not to expend all their energies on defending a [particular] date for the Exodus when the real debate today is whether the books of Exodus-Judges contain any history at all and if there was a sojourn and an exodus.”[15]

For Latter-day Saints, the historicity of the biblical account takes on added importance because allusions to the life of the prophet Moses and the events of the Exodus are referred to prominently in the Book of Mormon,[16] the Joseph Smith Translation,[17] the Doctrine and Covenants,[18] and the Pearl of Great Price.[19] Happily, modern revelation provides reliable, though not always complete, guidance on the interpretation of some disputed biblical passages and often points our attention to which details of ancient scripture should be taken most seriously in light of the Bible’s acknowledged imperfections.[20]

Summing up the scholarship on the historical context for the Exodus in this short article would be easier were the stakeholders more in accord and less passionate in their views. The distinguished Bible scholar Richard Elliott Friedman describes the difficulty of a fair and comprehensive discussion of the issues as follows:[21]

The quantity of interest means a quantity of different treatments at a quantity of different levels. You can find everything from nutty “theories” to serious, respectable scholarship. People blow small items out of proportion. People focus on items of evidence without taking into account other evidence that challenges or outweighs those points. People deny that it happened. People insist that it happened. People say that it happened but not the way the Bible tells it.

According to Bible scholar Joshua Berman, the essence of the case against the historicity of Exodus “can be stated in five words: a sustained lack of evidence.”[22] He continues:

Nowhere in the written record of ancient Egypt is there any explicit mention of Hebrew or Israelite slaves, let alone a figure named Moses. There is no mention of the Nile waters turning into blood, or of any series of plagues matching those in the Bible, or of the defeat of any pharaoh on the scale suggested by the Torah’s narrative of the mass drowning of Egyptian forces at the sea. Furthermore, the Torah states that 600,000 men between the ages of twenty and sixty left Egypt; adding women, children, and the elderly, we arrive at a population in the vicinity of two million souls. There is no archaeological or other evidence of an ancient encampment that size anywhere in the Sinai desert. Nor is there any evidence of so great a subsequent influx into the land of Israel, at any time.

No competent scholar or archaeologist will deny these facts.

However, according to Berman and other scholars who see a historical core to the story of the Exodus, reasonable responses are available for most of these issues. I will discuss a selection of these one by one. Because of limited space, the article will focus more on possible conclusions that it will on the rationales that led to them. As usual, suggestions for further reading are given at the end of the article.

After considerable thought and study on the subject, my opinions on the subject have developed to the point that I feel confident in sharing them with others. Though I have consulted many other works, in the end I have decided draw heavily on a book by Friedman on the Exodus written for non-specialists. It was favorably reviewed by the Deseret News when it first appeared in September 2017.[23]

More of a biblicist than an archaeologist, Friedman is a seasoned scholar who commands broad respect among his colleagues, both for his original scholarship and also for his ability to explain issues in a way that can be easily grasped by the layman. In his book on the Exodus, he uses his gifts to outline a broad theory of how the events of the historical Exodus might have unfolded. While — understandably — not answering every thorny question once and for all,[24] his theory takes seriously both the latest scholarship relating to the Bible while also accounting for evidence unearthed by mainstream archaeologists.

How the Historic Events Might Have Unfolded in Light of Current Scholarship

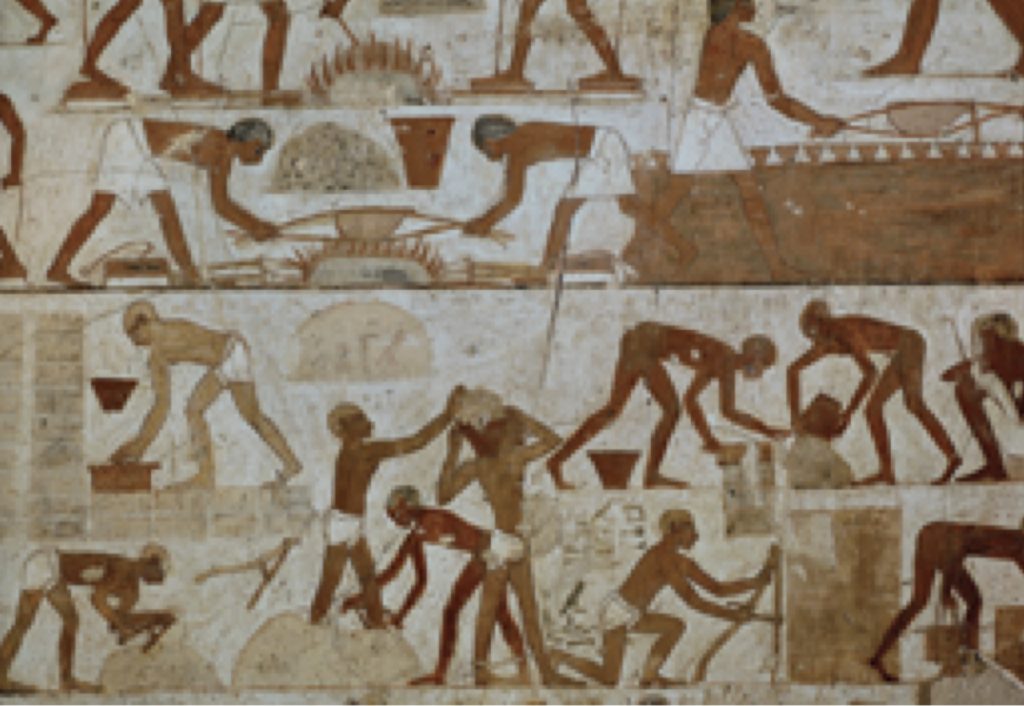

Figure 3. Papyrus Anastasi VI, ca. 1200 BCE.[25] This letter, possibly a model for the instruction of Egyptian scribes, mentions a group of Semitic nomads (Egyptian shasu) coming from the Sinai desert. “While the shasu mentioned here are probably not Israelites, the text does show is that it was not unusual for nomadic Semites to enter Egypt at this time especially along the eastern border of the Delta.”[26]

Is there evidence for large groups of Semitic emigrants having lived in Egypt? Yes. One thing on which virtually all serious scholars agree is “that there were Western Asiatic people in Egypt” for long periods of time preceding the plausible time period of the Exodus:

Call them Asiatics, Semites, Canaanites, Levantine peoples. But whatever we call them, these aliens were there, for hundreds of years. The literature on this is voluminous. They were everything from lower class and slaves (called variously Shasu, ‘Apiru, Habiru) to a dynasty of Pharaohs (the Hyksos, the Fifteenth Dynasty). And they were coming and going all along, just not in millions at a time. We could say: there were many “exoditos.” The idea that our exodus was one of these is well within reason.

Were all of the Semitic emigrants who came to Egypt part of Jacob’s family? No. It is certain that different groups of these emigrants came to Egypt at different times and, of course, not all of them were from the same family. Not surprisingly, these diverse peoples seem also to have been represented in the group who left Egypt at the time of the Exodus.[27] Jacob’s family no doubt intermarried with other groups over the years they stayed in Egypt. Exodus 12:38 specifically says that “a mixed multitude went up also with [those who left in the Exodus].” Indeed, the Hebrew term for “mixed” means “intermarried.”[28]

Considering the precedents in the Bible’s report of Abraham’s apparent missionary efforts to the peoples of the land[29] and, likewise, the implied consent of Jacob to his sons’ (deceitful) proposal to allow his children to intermarry with the inhabitants of Shechem conditional on their prior circumcision,[30] it is plausible that later, in Egypt, many Semites eventually became part of the covenant people. Indeed, some of these people may have already been worshippers of Jehovah before they came to Egypt.

As a later example, Rendsburg observes that Jerusalem “was incorporated into Israel by King David ca. 1000 BCE. The city was not destroyed, the population was not killed; rather, the residents simply became part of the nation of Israel. This fact would be remembered centuries later when the prophet Ezekiel would address the city with the words, ‘Your origin and your birthplace is from the land of the Canaanites, your father was an Amorite and your mother was a Hittite.'”[31]

Book of Mormon readers will note that the apparent assimilation of other peoples into the tribes of Israel parallels the situation of the Nephites and the Lamanites where, even though the original distinction was lineage-based, it is known that each group eventually came to include like-minded associates in addition to actual descendants.[32] Indeed, many of the first New World ancestors of those who eventually came to be called Nephites or Lamanites could not have traced their lineage to Lehi — not only including the Jaredites and Mulekites but also potentially indigenous inhabitants of the Americas.[33]

Are the large numbers of Israelites who left Egypt given in Exodus believable to archaeologists? Most reputable scholars of all stripes would say no. However, as Friedman points out, the lack of material remains for the Exodus in Egypt or Sinai is not “evidence about whether the exodus happened or not.[34] It is evidence only of whether it was big or not”:[35]

For heaven’s sake, did we need archaeological work to confirm that an exodus of two million people was, shall we say, problematic? It had already been calculated long ago that if the people were marching, say, eight across, then when the first ones got to Mount Sinai, half of the people were still in Egypt. … Did we really need archaeologists combing the Sinai and not finding anything to prove what we knew anyway? The absence of exodus and wilderness artifacts questions only whether there was a massive exodus.

Elsewhere Friedman explains:[36]

There is no archaeological evidence against the historicity of an exodus if it was a smaller group who left Egypt. Indeed, significantly, the first biblical mention of the Exodus, the Song of Miriam, which is the oldest text in the Bible, never mentions how many people were involved in the Exodus, and it never speaks of the whole nation of Israel. It just refers to a people, an am, leaving Egypt.

We find the same picture that Friedman paints of an uncertain number of people leaving Egypt in modern scripture. In addition, though the story of the Exodus is referenced many times in the revelations and translations of the Prophet, the size of the group is never specified or implied.

Were all the tribes equally represented in the Exodus? One of the most significant and controversial aspects of Friedman’s theory about the Exodus was originally suggested by the eminent Bible scholar David Noel Freedman decades ago. It is that the group of those who left Egypt, if not exclusively Levite, were at least dominated by the Levites:[37]

The Levites were the group who later became the priests of Israel and some of the main authors of the Bible. The Bible identifies them as the group that was connected with Moses and his family. The story says that both his mother and his father were Levites. What if it was just the Levites who made the flight from Egypt?

As a glimpse of one of several evidences Friedman presents for the prominence of Levi in Egypt, he observes:[38]

Out of all of Israel only Levites had Egyptian names: Moses,[39] Phinehas, Hophni, and Hur are all Egyptian names. We in the United States and Canada, lands of immigrants, are especially aware of how much names reveal about people’s backgrounds. The names Friedman, Martinez, and Shaughnessy each reveal something different about where they came from. Levites have names that come from Egypt. Other Israelites don’t.

Friedman’s restriction of the group leaving Egypt to just the Levites no doubt goes too far. For example, given that the JST Genesis 50 version of Joseph’s testament[40] prophesies that Joseph’s descendants would be freed by Moses, LDS readers will see the wisdom of concluding that at least some of Joseph’s posterity and almost certainly others of the family of Jacob were included in the Exodus group. The apparent dominance of Levi in the biblical account may be due not only to their presumed numerical advantage but also because of the prominence of Moses as prophet, as well as the role of the larger group of Levites as the priests, scribes, and teachers who collected and recorded the history.

If Levi was the dominant group in Egypt at the time of Moses, where were all the other Israelites? Some — or, more likely, most — returned before the Exodus led by Moses or had stayed behind in Canaan to begin with. The eminent archaeologist William Dever states the consensus view based on decades of careful analysis of material remains for the settlement of ancient Canaan, namely: “overwhelming … evidence today of largely indigenous origins for early Israel.”[41] Some evidence of a more direct nature has been claimed already for the tribes of Asher and Dan.[42]

Scholars base their conclusions largely on repeated findings that, with a very few exceptions, there is no evidence for military conquest of Canaan;[43] nor does research reveal a large influx of new settlers with a culture and religion differing from the region’s previous inhabitants. In other words, most of the Israelites:[44]

did not come from Egypt or anywhere else. They were just there as far back as we can trace them. Dever meant [his statement] as evidence against the Exodus. But, as I have been saying, it is evidence only against an exodus of all of Israel. The Israelite tribes had “largely indigenous origins.” Most of them were in Israel all along. That fits fine with the evidence that just the Levites came from Egypt. Then the Levites united with those Israelite tribes. … We do not doubt that this union of Levites and the Israelite tribes took place … because the Levites have been counted among the people of Israel from biblical times until the present day.

According to Friedman, it’s a viable possibility that “these Levites had originally come from Israel (probably called Canaan at that point) themselves, so their uniting was actually a re-uniting with their old brethren.”[45] The same would have applied to any others of the family of Jacob who were part of the Exodus.

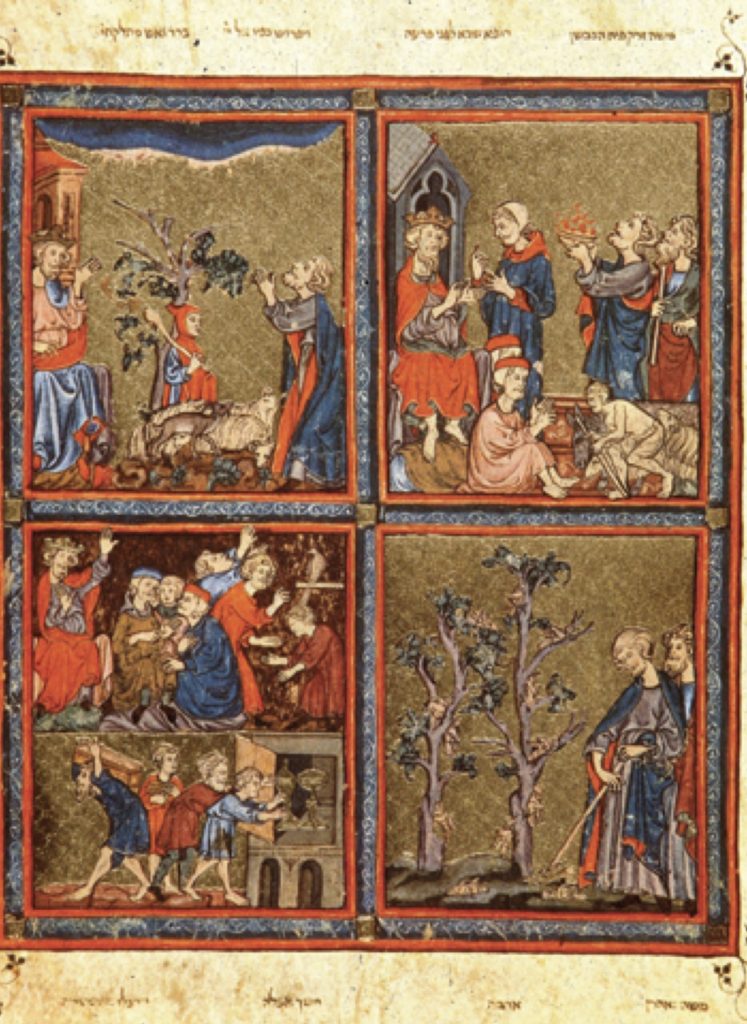

Figure 4. Four of the plagues as depicted in the Golden Hagada, an illustrated Hebrew manuscript from Spain, 1320 CE[46]

Besides the fact that Egyptian names occur only among the Levites, is there any biblical evidence for Friedman’s theory? Friedman says yes, “and it comes from one of the earliest writings in the Bible, the Song of Deborah, composed in Israel in the 12th or 11th century BCE.”:[47]

After the Canaanites suffer a major defeat, Deborah summons the victorious tribes of Israel. In uniting the tribes, which constitutes the founding event of Israel’s history as a nation in its land, ten of the tribes are summoned — but noticeably absent is Levi. Their absence is perfectly consistent with all of the other facts we have observed. The Levites weren’t there in Israel yet; they were in Egypt. Think of this: The two oldest texts in the Bible are the Song of Deborah[48] and the Song of Miriam.[49] The Song of Deborah, in Israel, doesn’t mention Levi. The Song of Miriam, in Egypt, doesn’t mention Israel! …

So they reached an agreement: The Levites got the [prerogatives that went with the] priesthood, which included some cities[50] plus a tithe (10%) of Israel’s produce.[51] One of the Levites’ main tasks as priests was to teach Torah to the Israelite people. Deuteronomy 33:10 says, “They’ll teach your judgments to Jacob and your Torah to Israel.” Leviticus 10:11 commands that they are to teach what God spoke through Moses. Naturally, when the Levites taught Torah, they taught the tradition they had brought with them out of Egypt. And that is how every Israelite child learned, “We were slaves in Egypt and God brought us out with a strong hand and an outstretched arm.”[52] Much later, this Torah passage was placed in the haggadah — which is how most of us know it today. And that is how a historical event that happened to the Levite minority became everybody’s celebration — how we all came to say that we were slaves in Egypt, although that was not the experience even of most Israelites of the period. It’s not so different from practicing, say, the American cultural tradition of Thanksgiving, which most Americans do, even though most U.S. citizens are not descended from Pilgrims or Native Americans.[53]

Does Friedman’s theory help account for the differences in used for for God in different sources in the Bible? Friedman gives many pieces evidence within the Bible itself for some of the main points of his theory that we cannot detail here.[54] One example he highlights is that the teachings of the Levites were crucial in establishing that Yahweh was the name of their God, in distinction to the Canaanites who worshiped El:[55]

The Levites worshipped the God Yahweh, while the Israelite tribes worshipped the God of Canaan: El. … [But] the tribes decided that El and Yahweh were one, in essence saying, “the same God by a different name.” That explains why two of the Levite-authored sources (E and P) both developed the point that God was known as El until the time of the Exodus, and then God revealed to Moses that his true personal name was Yahweh.[56] El and Yahweh were one and the same.

Despite apparent efforts to unify the worship of God around the Jerusalem temple and the worship of Jehovah that continued through the time of the united monarchy, older forms of folk worship native to Canaan persisted and then made a strong comeback once the kingdom was divided.[57] Prophets upbraided both Israel and Judah for their apostasy.

When Did the Exodus Take Place?

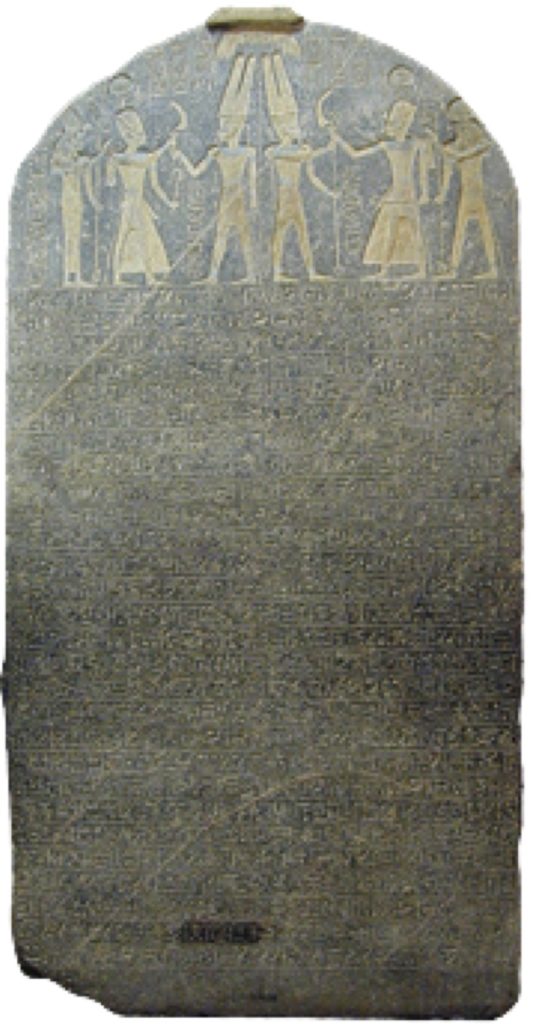

Figure 5. The Merneptah Stele, ca. 1205 BCE58 The stele famously (and probably falsely)

claims that “Israel is laid waste, his seed is no longer”

Does the idea that some of the Israelites were already in Canaan when the others arrived help us in finding a date for the Exodus? No. Although Friedman’s interpretation of events has important implications for the dating of the Exodus, it actually widens rather than narrows the options for the range of likely dates.

The Merneptah Stele often has been thought of as providing a key piece of evidence for this dating. It is sometimes called the “Israel Stele” because it is the first known mention of Israel as a people. Scholars firmly date it to about 1205 BCE, during the reign of the Egyptian Pharaoh Merneptah. In the stele Merneptah claimed to have annihilated the people of Israel.

For those who see all of Israel arriving in Canaan and becoming “a settled people by 1205, … the exodus had to be before that [date]. Also, some [have] pointed out that the Egyptian military controlled the Sinai Peninsula at that time, so a huge mass of escaped slaves slipping by there would have been impossible then. But the flaw in this picture is that it still presumes that all of Israel made the Exodus and then arrived in Canaan. If it was [a smaller group] who made the Exodus, while the rest of Israel was back in their land, then this whole argument disappears. … [The] exodus could have been before or after Pharaoh Merneptah.” Friedman continues:[59]

The Merneptah stele confused things as long as people were picturing the entire nation of Israel making the exodus. They had to picture the exodus taking place long before Merneptah’s time: with millions leaving Egypt, journeying through the Sinai wilderness for a whole generation, arriving and conquering and settling in the land, all without leaving a sign in Egypt, Sinai, or Israel of any of those things happening. But as we [have seen], if it was [a smaller group], then their exodus could have been before or after Merneptah. The stele is still important. It just does not happen to be evidence for the date of the Exodus. It is not evidence that Israel was in Egypt. It is evidence that Israel was in Israel! What matters — matters enormously — is that Israel the people [were] already there when the [group from Egypt] arrived.

Figure 6. The grand mortuary temple of Ramesses II which has come to be known as the Ramesseum. The annual flooding of the Nile contributed to its current ruined state. Photograph by Stephen T. Whitlock.

What can we infer from all this about the Pharaoh(s) of the Exodus? Most readers of the Bible wish that the editor of Exodus had given the name for the pharaohs of the Exodus. Indeed, some argue that lack of a given name is evidence that no Exodus happened. Though Friedman does not come to any firm conclusion about the names of the pharaohs, he thinks there may have been good reasons for not including the names, assuming they were even known at the time the book of Exodus as we have it took its current form.[60]

In my opinion, Gary Rendsburg gives the most convincing case so far for the identity of the pharaohs of the Exodus, one that is not inconsistent with the textual and archaeological evidence presented above. For those who would like to know more, Rendsburg has outlined the reasons for his views in a short, easy-to-read Web post[61] and two longer, more technical articles.[62]

Speaking generally about the dating of the Exodus, Rendsburg sees five major reasons that “whatever history may underlie the Bible’s narrative should be placed in [the] general timeframe” of the nineteenth and twentieth Egyptian dynasties (1250-1175 BCE), noting that “all of these find echoes in the Bible, whether they be true reflexes of the biblical account or serve as good parallels to recorded episodes”:

In light of these points and other evidence, Rendsburg gives this brief summary of his conclusions about the pharaohs of the Exodus:[67]

Figures 7a, b. Heads of the mummies of Ramesses II and Ramesses III.

Ramesses II was a successful builder of great cities, temples, and monuments and died at the age of 90 or 91. By way of contrast, Ramesses III presided over Egypt’s decline. His reign was marked by constant war and exhaustion of the treasury that were belied by the image of continuity and greatness projected in his own monumental building program.[72] A conspiracy apparently ended his life as well as that of another man buried with him — presumably his son Pentaweret. A study reported in part in the British Medical Journal “stated that conspirators murdered pharaoh Ramesses III by cutting his throat.”[73] Hence, the “excessive bandages” around the neck of his mummy.

In remembering the arrival of the small group of pioneers in the Salt Lake valley in July 1847, Latter-day Saints will resonate with the fact that a relatively small group of courageous and devoted predecessors can leave a large legacy with enduring impact on generations to follow. If Friedman is correct that the Levites were the dominant group of the Exodus (as is at least apparent in the leadership of Levites Moses and Aaron), they would have provided similar models of faith and faithfulness for Israelites living in a land dominated by competing religious beliefs and practices. Moreover, in their appointed roles as priests and teachers to Israel, their memories of the Exodus and intimate acquaintance with the laws and revelations received by Moses would have been a blessing to their people.

In this sense, we might think of the Israelites of the Exodus in Book of Mormon terms as branches of the tree of Israel planted for a time elsewhere in the Lord’s vineyard and ultimately destined to be grafted back “into the tree from whence they came,” that the mother “tree [might] not perish, that, perhaps, [He] might preserve unto [Himself] the roots thereof for [His] own purpose.”[74]

Thanks to Stephen T. Whitlock for allowing me to include his photograph of the Ramesseum and for other valuable suggestions.

For a readable book-length account of Friedman’s views of the issues and perspectives discussed in this article, see R. E. Friedman, Exodus. For a shorter version, see this Web post: R. E. Friedman, Exodus is Not Fiction

A video version of a presentation by Friedman on the subject entitled “The Exodus Based on the Sources Themselves” can be found at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H-YlzpUhnxQ. The presentation was given as part of the University of California San Diego Exodus Conference “Out of Egypt: Israel’s Exodus Between Text and Memory, History and Imagination,” May 31-June 1, 2013. Presentations giving a wide diversity of perspectives by virtually every major figure in Exodus scholarship can be found in video format at http://exodus.calit2.net and in the published volume that resulted from the conference: B. B. Levy, et al., Israel’s Exodus. See also this publication from a follow-on conference by conservative scholars: A. R. Millard, et al., Did I Not Bring Israel.

Bible scholar Joshua Berman, whose views will be explored more thoroughly in the next article in this series, led an online debate with supporters and skeptics in Mosaic Magazine (J. A. Berman, Was There an Exodus?).

A variety of evidences and arguments for the historicity of the Exodus are made in these volumes by the well-respected evangelical archaeologist James K. Hoffmeier: J. K. Hoffmeier, Israel in Egypt; J. K. Hoffmeier, Ancient Israel in Sinai. A recent volume edited by Hoffmeier and Dennis R. Magary argues for the importance of history for faith (J. K. Hoffmeier, et al., Do Historical Matters?).

For Gary Rendsburg’s views on the general timeframe and pharaohs of the Exodus, see the Web post: G. A. Rendsburg, Pharaoh of the Exodus. For longer, technical treatments of the subject, see G. A. Rendsburg, Date of the Exodus; G. A. Rendsburg, Early History of Israel.

William Dever, who has been hailed by scholars from many different persuasions as “the dean of North American Syro-Palestinian archaeologists,”[75] has cogently summarized the archaeological evidence and theories relating to the early history of Israel in W. G. Dever, Beyond the Texts. See also W. Dever, What Did the Biblical Writers.

Dever gave an entertaining and informative presentation sponsored by the Academy for Temple Studies on the persistence of folk religion among the Israelites in Logan, Utah on 23 October 2013 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hjx1c3NAVTQ). He has also written a book on the topic (W. G. Dever, Did God Have a Wife?).

Perspectives illuminating similar issues in Book of Mormon archaeology can be found at Book of Mormon Central:

For other scripture resources relating to this lesson, see The Interpreter Foundation Old Testament Gospel Doctrine Index (https://interpreterfoundation.org/gospel-doctrine-resource-index/ot-gospel-doctrine-resource-index/) and the Book of Mormon Central Old Testament KnoWhy list (https://knowhy.bookofmormoncentral.org/tags/old-testament).

Alter, Robert, ed. The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary. New York City, NY: W. W. Norton, 2004.

Asad, Talal. "The construction of religion as an anthropological category." In Genealogies of Religion: Discipline and Reasons of Power in Christianity and Islam, edited by Talal Asad, 27-54. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993.

Attridge, Harold W., Wayne A. Meeks, Jouette M. Bassler, Werner E. Lemke, Susan Niditch, and Eileen M. Schuller, eds. The HarperCollins Study Bible, Fully Revised and Updated Revised ed. New York City, NY: HarperOne, 2006.

Berman, Joshua A. 2015. Was there an Exodus? In Mosaic Magazine. http://mosaicmagazine.com/essay/2015/03/was-there-an-exodus/. (accessed June 27, 2015).

———. Inconsistency in the Torah: Ancient Literary Convention and the Limits of Source Criticism. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Bosworth, F. F. 1924. Christ the Healer. Ninth ed. Grand Rapids, MI: Fleming H. Revell, Baker Book House, 2000. http://www.despatch.cth.com.au/Books_V/Christ%20the%20Healer%20-%20F.%20F.%20Bosworth.pdf. (accessed April 1, 2018).

Bowman, Matt. 2017. Book review: Scholar hunts for historical evidence of biblical Exodus. In Deseret News. https://www.deseretnews.com/article/865691157/Book-review-Scholar-hunts-for-historical-evidence-of-biblical-Exodus.html. (accessed March 31, 2018).

Dever, William. What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It? What Archaeology Can Tell Us about the Reality of Ancient Israel. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2002.

Dever, William G. Did God Have a Wive? Archaeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2005.

———. Beyond the Texts: An Archaeological Portrait of Ancient Israel and Judah. Atlanta, GA: SBL Press, 2017.

Draper, Richard D., S. Kent Brown, and Michael D. Rhodes. The Pearl of Great Price: A Verse-by-Verse Commentary. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005.

Friedman, Richard Elliott. 2014. The Exodus is not fiction: An Interview with Richard Elliott Friedman. In Reform Judaism Magazine. https://reformjudaism.org/exodus-not-fiction. (accessed March 31, 2018).

———. The Exodus: How It Happened and Why It Matters. New York City, NY: HarperOne, 2017.

Hoffmeier, James K. Israel in Egypt: The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus Tradition. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1996.

———. Ancient Israel in Sinai: The Evidence fot eh Authenticity of the Wilderness Tradition. New York City, NY: Oxford University Press, 2005.

———. "What is the biblical date for the Exodus? A response to Bryant Wood." Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 50, no. 2 (June 2007): 225-47.

Hoffmeier, James K., and Dennis R. Magary, eds. Do Historical Matters Matter to Faith? A Critical Appraisal of Modern and Postmodern Approaches to Scripture. Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2012.

Holland, Jeffrey R. "’Lord, I believe’." Ensign 43, May 2013. https://churchofjesuschrist.org/general-conference/2013/04/lord-i-believe?lang=eng. (accessed April 1, 2018).

———. 2017. The greatness of the evidence (Talk given at the Chiasmus Jubilee, Joseph Smith Building, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, 16 August 2017). In Mormon Newsroom. http://www.mormonnewsroom.org/article/transcript-elder-holland-speaks-book-of-mormon-chiasmus-conference-2017. (accessed August 18, 2017).

Levy, B. Barry, Thomas Schneider, and William H. C. Propp, eds. Israel’s Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective: Text, Archaeology, Culture, and Geosciance. Quantitative Methods in the Humanities and Social Sciences. Berlin, Germany: Springer, 2015.

Lindsay, Jeff. "Joseph and the amazing technicolor dream map: Part 2 of 2." Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 16 (2016): 247-326. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/joseph-and-the-amazing-technicolor-dream-map-part-2-of-2/. (accessed March 29, 2018).

Millard, Alan R., Gary A. Rendsburg, and James K. Hoffmeier. ‘Did I Not Bring Israel Out of Egypt?’: Biblical, Archaeological, and Egyptological Perspectives on the Exodus Narratives. Bulletin for Biblical Research Supplement. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2016.

Nibley, Hugh W. 1957. An Approach to the Book of Mormon. 3rd ed. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 6. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1988.

Pleins, J. David. When the Great Abyss Opened: Classic and Contemporary Readings of Noah’s Flood. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Ramesses III. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ramesses_III. (accessed April 3, 2018).

Rendsburg, Gary A. "The date of the Exodus and the conquest/settlement: The case for the 1100’s." Vetus Testamentum 42 (1992): 510-27.

———. "The early history of Israel." In Crossing Boundaries and Linking Horizons: Studies in Honor of Michael C. Astour on His 80th Birthday, edited by Gordon Douglas Young, Mark W. Chavalas and Richard E. Averbeck, 433-53. Bethesda, MD: CDL Press, 1997.

———. n.d. The pharaoh of the Exodus — Rameses III. In The Torah.com: A Historical and Contextual Approach. http://thetorah.com/the-pharaoh-of-the-exodus-rameses-iii/. (accessed March 28, 2018).

Rolston, Holmes, III. 1987. Science and Religion: A Critical Sruvey. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2006.

Sorenson, John L. An Ancient American Setting for the Book of Mormon. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1985.

Talmage, James E. 1931. "The earth and man (originally published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Deseret News, November 21, 1931, pp. 7-8)." In Science and Mormonism: Cosmos, Earth, and Man, edited by David H. Bailey, Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, John H. Lewis, Gregory L. Smith and Michael L. Stark. Interpreter Science and Mormonism Symposia 1, 335-51. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2016. https://archive.org/details/CosmosEarthAndManscienceAndMormonism1. (accessed 1 April 2018).

Taylor, Charles. A Secular Age. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2007.

Uchtdorf, Dieter F. "Come, join with us." Ensign 43, November 2013. https://churchofjesuschrist.org/general-conference/2013/10/come-join-with-us?lang=eng. (accessed April 1, 2018).

Wells, Bruce. "Exodus." In Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, edited by John H. Walton. Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary 1. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2009.

How is it that the biblical texts are always approached with postmodernism’s typical “hermeneutic of suspicion,” but the non-biblical texts are taken at face value? It seems to be that the Bible is automatically held guilty unless proven innocent.

Some will say: It does not matter if it is historical or not. What matters is what it has meant, the exodus’ meaning to religion over the centuries. That is a lovely thought. I used to say it sometimes myself. But nowadays I find myself saying: Whom are we kidding? We want to know if it happened, or if what people have been believing for millennia is an illusion, an invention. It matters plenty to people whether it happened or not. There is an anti-historical wind blowing lately. People claim that we cannot really recover what happened in the past: we do not have history. But something happened. We can recover some of it from real evidence and reasoning. There are other parts of it that we cannot exhume. We also happen to have some great stories about it, a fabulous narrative. We have both, and we can study both: history and narrative. They are both great enterprises—as long as you tell people which you are doing at the time.

Early reports of this study understood it to have traced cohanim [members of the Jewish priestly lineage presumed to be descendants of Aaron] to a single male ancestor who lived around three millennia ago. Subsequent studies more carefully spoke of a small group of ancestors, not just a single individual. Dr. Skorecki told me more succinctly: “Not a single paternal lineage, but a very small number.” …

If this is right, then what should we expect genetically? Cohanim, starting from a small group, perhaps a family or clan, should be related genetically. Levites, starting from a large, diverse group of immigrants from Egypt, should be diverse genetically. Cohanim are related by DNA. Levites are not related by DNA; they are related by common history. And that is just what the genetic research showed.

Some archaeologists had said, “We’ve combed the Sinai and didn’t find anything.” But an Israeli archaeologist laughed at that claim and told me, “It was five jeeps.” It was a survey, not an excavation of the whole Sinai Peninsula. Moreover, even if we had excavated the whole Sinai, what could we find that people traveling from Egypt to Israel around thirty-three hundred years ago would have left that we would dig up now? A piece of petrified wood with “Moses loves Zipporah” carved in it? An Israeli archaeologist told me that a vehicle that was lost in Sinai in the 1973 war was found recently under sixteen meters of sand. Sixteen meters down in forty years (a biblical number)! Finding objects thirty-three hundred years down presents a rather harder challenge. And, above all, our archaeological work did not turn up evidence to show that an exodus did not happen. What it turned up was nothing, an absence of evidence. And some archaeologists then interpreted this nothing to be proof that the event did not happen. On the other side, people who challenged such interpretations were fond of quoting the old principle: “Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.”

Some tried to account for the huge number of 603,550 males (hence two million) by asserting that the Hebrew word for “thousand” (‘eleph) actually means “clan.” But in over 250 occurrences in the Hebrew Bible the word ‘eleph regularly means thousands and is joined alongside the word for hundreds in giving total numbers. And the number of firstborn Israelite males in the biblical census is 22,273 (Numbers 3:43). Since firstborn sons as a group do not constitute clans, this confirms that those who take the word for “thousand” in the census to mean “clan” are mistaken.

She called his name Moses — Hebrew mosheh — because she drew — Hebrew root mashah — him from the water. I have always told my students that the translation of his name in English should be Drew. So it would be that she says, “I’ll call his name Drew, because I drew him from the water.” Puns do not usually translate. But this is a really good exception.

In this case our archaeological evidence indicates that no such arrival of conquering masses ever took place—the destruction layers are just not there on the sites—and our earliest source, the Song of Miriam, does not mention it. Where we do find a destruction layer is at the site of the city of Hazor, but that fits better with the account of Deborah’s defeat of the king of Hazor, to which we referred earlier, or it could have happened at some other time. Without all the other cities, it does not add up to Joshua or a widespread conquest of the land. The archaeologists are right: there was no conquest.

- Eight out of eight Israelites with Egyptian names are Levites.

- Two out of two accounts of the revelation of God’s name make it to the Levite Moses and are told in Levite sources.

- The massive treatment of the Tabernacle, which parallels the Egyptian tent of Ramesses II, appears in the Levite Priests’ sources.

- The ark, which is entrusted to the Levites, parallels the Egyptian barks.

- Seven out of seven items of Egyptian lore that come up in the biblical story occur in Levite sources.

- Eleven out of eleven references to circumcision in legal context, literal or metaphorical, occur in Levitical sources in the Torah and the prophets.

- And the two references to it in stories involve the Levite Moses or Levi himself.

- Three out of three sources that tell the story of the plagues and exodus are Levite sources.

- All texts treating slavery during and after the Egyptian stay are Levite sources.

- Fifty-two out of fifty-two references to aliens occur in Levite sources.

- Fifty-two references to the sanctuary (miqdash) in the Bible, which is where the people in the Song of the Sea go, identify it as the Temple or Tabernacle, the shrines to which only the Levites are allowed access. The non-Levite source(s) lack all of this.

It took a variety of scholars, each contributing a piece of the puzzle, to arrive at this picture. Homan saw the connection between the Tabernacle and Ramesses’ tent. Noegel saw the connection between the ark and the Egyptian barks. Rendsburg saw the connection between the Exodus stories and the stories that we know from Egyptian culture. Freedman saw the connection between the Song of the Sea and the Song of Deborah. Propp saw the connection of the word levi and the role of aliens. And a host of scholars saw the significance of the presence of Semites, Asiatics, Shasu, ‘Apiru (Habiru), Hyksos — Levantine people in Egypt in those centuries. And we can now unite all of this in the context of what we know about the Bible’s sources: the texts and the people who wrote them.

Some have raised another argument to suggest that the story is made up. Specifically: unnamed pharaohs. I wrote in my commentary on the Torah that there are five pharaohs in the Torah: a pharaoh who thought that Sarah was Abraham’s sister, the pharaoh who knew Joseph, the pharaoh who did not know Joseph and oppressed the Israelites, the pharaoh who sought to kill Moses (who may or may not be the same pharaoh who did not know Joseph), and the pharaoh of the exodus. Why are not any of their names given? Names of pharaohs do appear in later books (Shishak, Necho). Their absence in the Torah gives the narrative a nonhistorical quality, which is contrary to the manifest aim of the authors to present history. So some argue that this is evidence that the stories are not true, that they were invented by writers who could not name these kings because they had no idea of the names of ancient pharaohs. In the case of the two pharaohs in Genesis we have hardly any evidence to argue for or against this. But in the case of the exodus pharaohs, we have seen sufficient likelihood that the oppression and exodus are historical so that we must at least consider whether there could be other reasons why the pharaohs are not named. My friend Jonathan Saville suggests that perhaps the reason, consciously or not, was to downgrade the pharaoh, as when people sometimes avoid saying the name of someone to whom they feel hostile. I also keep in mind a lesson I learned from my teacher Professor Cross, who used to say: the most banal explanation is usually the right one. Perhaps the names of the pharaohs simply were no longer preserved in memory or written tradition by the time the stories came to be written. The authors no longer had any sources that recorded (or cared about) the pharaohs’ names. They cared about preserving names that mattered much more to them: Levi, Moses, Aaron, Miriam, Zipporah, even the midwives Shiphrah and Puah. These are the names of the story’s heroes. But did the authors care whether it was Pharaoh Ramesses II or Ramesses III? Or Merneptah? Apparently not. An absence of pharaohs’ names does not mean an absence of an exodus. Indeed, there may not have been any single pharaoh’s name to remember. … We do not know if any one pharaoh stood out as their prime oppressor.

Of some interest is another Egyptian document, P. Anastasi V 19: 2-20:6 from the reign of Seti II (1205–1200). This text includes the report of another frontier official, also stationed at Tjeku. After the typical formalities at the beginning of the letter, we read as follows:

Another matter, to wit: I was sent forth from the broad halls of the palace, life, prosperity, health, in the 3rd month of the 3rd season, day 9, at evening time, following after two slaves. Now when I reached the wall of Tjeku on the 3rd month of the 3rd season, day 10, they told me that to the south they were saying that they [i.e. the slaves] had passed by on the 3rd month of the 3rd season, day 10. When I reached the fortress, they told me that the scout (?) had come from the desert stating that they had passed the walled place north of Migdol of Seti Merneptah, life, prosperity, health, beloved like Seth. When my letter reaches you, write to me about all that has happened to them. Who found their tracks? Which watch found their tracks? What people are after them? Write to me about all that has happened to them and how many people you sent out after them.

Once more there are parallels between an Egyptian document and the biblical account. Regardless of the manner in which the Torah presents Israel’s history, it is noteworthy that the account includes an Egyptian force sent to pursue escaped slaves (Exod14: 5-9). The above document informs us that this was perfectly natural, in fact, when even only two slaves escaped. Moreover, the route of the two escaped slaves is significant. The two sites mentioned are Tjeku and Migdol. Though some scholars are still skeptical, there is no objection to equating Tjeku with biblical Sukkot, the very site mentioned as the Israelites’ point of departure (Exodus 12:37; 13:20). Migdol, meanwhile, is also mentioned in the biblical account (Exodus 14:2). One gains the impression that the Israelites were utilizing a route well traveled by escaping slaves, a type of “underground railway.”